The Albert Schweitzer Foundation

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2021 |

Archived Version: November, 2021

What does ASF do?

The Albert Schweitzer Foundation (ASF) was founded in 2000. ASF primarily works in Germany, though they also have a team in Poland. ASF operates as a nonprofit rather than a typical grantmaking foundation. They work to improve animal welfare standards through corporate outreach, consumer campaigns, and legal work. In addition, ASF works to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement by organizing workshops and public events.

What are their strengths?

We believe that ASF’s corporate outreach program to implement animal welfare standards is effective and targets high-priority animal groups. ASF’s plans and projections indicate they would be able to effectively utilize an increase in income. While the impacts of ASF’s legal, legislative, and lobbying activities are often indirect—therefore, their cost effectiveness is more difficult to evaluate—we are not concerned about this given their track record of achievements. ASF is transparent in its organizational structure and staff generally agree that the organization is led competently.

What are their weaknesses?

We have concerns about some reports of alleged discrimination or harassment that a few staff members believe were not handled appropriately. However, leadership has taken action to handle the complaints.

Programs

A charity that performs well on this criterion has programs that we expect are highly effective in reducing the suffering of animals. The key aspects that ACE considers when examining a charity’s programs are reviewed in detail below.

Method

In this criterion, we assess the effectiveness of each of the charity’s programs by analyzing (i) the interventions each program uses, (ii) the outcomes those interventions work toward, (iii) the countries in which the program takes place, and (iv) the groups of animals the program affects. We use information supplied by the charity to provide a more detailed analysis of each of these four factors. Our assessment of each intervention is informed by our research briefs and other relevant research.

At the beginning of our evaluation process, we select charities that we believe have the most effective programs. This year, we considered a comprehensive list of animal advocacy charities that focus on improving the lives of farmed or wild animals. We selected farmed animal charities based on the outcomes they work toward, the regions they work in, and the specific animal group(s) their programs target. We don’t currently consider animal group(s) targeted as part of our evaluation for wild animal charities, as the number of charities working on the welfare of wild animals is very small.

Outcomes

We categorize the work of animal advocacy charities by their outcomes, broadly distinguishing whether interventions focus on individual or institutional change. Individual-focused interventions often involve decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Institutional change involves improving animal welfare standards, increasing the availability of animal-free products, or strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

We believe that changing individual habits and beliefs is difficult to achieve through individual-focused outreach. Currently, we find the arguments for an institution-focused approach1 more compelling than individual-focused approaches. We believe that raising welfare standards increases animal welfare for a large number of animals in the short term2 and may contribute to transforming markets in the long run.3 Increasing the availability of animal-free foods, e.g., by bringing new, affordable products to the market or providing more plant-based menu options, can provide a convenient opportunity for people to choose more plant-based options. Moreover, we believe that efforts to strengthen the animal advocacy movement, e.g., by improving organizational effectiveness and building alliances, can support all other outcomes and may be relatively neglected.

Therefore, when considering charities to evaluate, we prioritize those that work to improve welfare standards, increase the availability of animal-free products, or strengthen the animal advocacy movement. We give lower priority to charities that focus on decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Charities selected for evaluation are sent a request for more in-depth information about their programs and the specific interventions they use. We then present and assess each of the charities’ programs. In line with our commitment to following empirical evidence and logical reasoning, we use existing research to inform our assessments and explain our thinking about the effectiveness of different interventions.

Countries

A charity’s countries and regions of operations can affect their work with regard to scale, neglectedness, and tractability. We prioritize charities in countries with relatively large animal agricultural industries, few other charities engaged in similar work, and in which animal advocacy is likely to be feasible and have a lasting impact. In our charity selection process, we used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI), which combines proxies for scale, tractability, and global influence to create country scores.4 To assess neglectedness, we used our own data on the number of organizations that we are aware of working in each country. Below we present these measures for the countries that ASF operates in.

Animal groups

We prioritize programs targeting specific groups of animals that are affected in large numbers5 and receive relatively little attention in animal advocacy. Of the 187 billion vertebrate farmed animals killed annually for food globally, 110 billion are farmed fishes and 66.6 billion are farmed chickens, making these impactful groups to focus on. There are at least 100 times as many wild vertebrates as there are farmed vertebrates.6 Given the large number of wild animals and the small number of organizations working on their welfare, we believe wild animal advocacy also has potential for high impact despite its lower tractability.

We recognize the enormous scale of invertebrates, both farmed7 and wild, and would like to see more resources go toward this group of animals. Because of the vast differences between invertebrate species and the state of evidence considering their sentience, programs need to be considered and prioritized on a case-by-case basis. However, because of the large number of individuals involved and the underrepresentation of invertebrate issues in the animal advocacy movement, we consider more programs advocating for them to be a priority. We believe the evidence regarding the sentience of any invertebrate species is inconclusive, but we believe that there are enough signs of potential sentience8 to err on the side of caution—especially considering the vast numbers of invertebrates and the high neglectedness of this issue.9

A note about long-term impact

Each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.10 The potential number of animals affected increases over time due to population growth and an accumulation of generations. Thus, we would expect that the long-term impacts of an action would likely affect more animals than the short-term impacts of the same action. Nevertheless, we are highly uncertain about the particular long-term effects of each intervention. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew toward overemphasizing short-term effects.

Information and Analysis

Cause areas

ASF’s programs focus exclusively on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we think is a high-priority cause area.

Countries

ASF develops their programs in Germany and Poland. Their headquarters are in Germany.

We used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index with the suggested weightings of scale (25%), tractability, (55%) and influence (20%) to determine each country’s total FAOI score. We report this score along with the country’s global ranking from a total of 60 countries in the following format: FAOI score(global ranking). Germany and Poland have the following scores and rankings, respectively: 33.52(3) and 21.07(15). According to the comprehensive list of charities we are aware of, there are about 724 farmed animal advocacy organizations, excluding sanctuaries, worldwide. From this list, we found 40 in Germany and three in Poland. We believe that farmed animal advocacy in Germany has a high level of tractability and global influence, according to its FAOI score. Additionally, farmed animal advocacy seems to be relatively neglected in Poland. Overall, we believe that both Germany and Poland are relatively high-priority countries for farmed animal advocacy work.

Description of programs

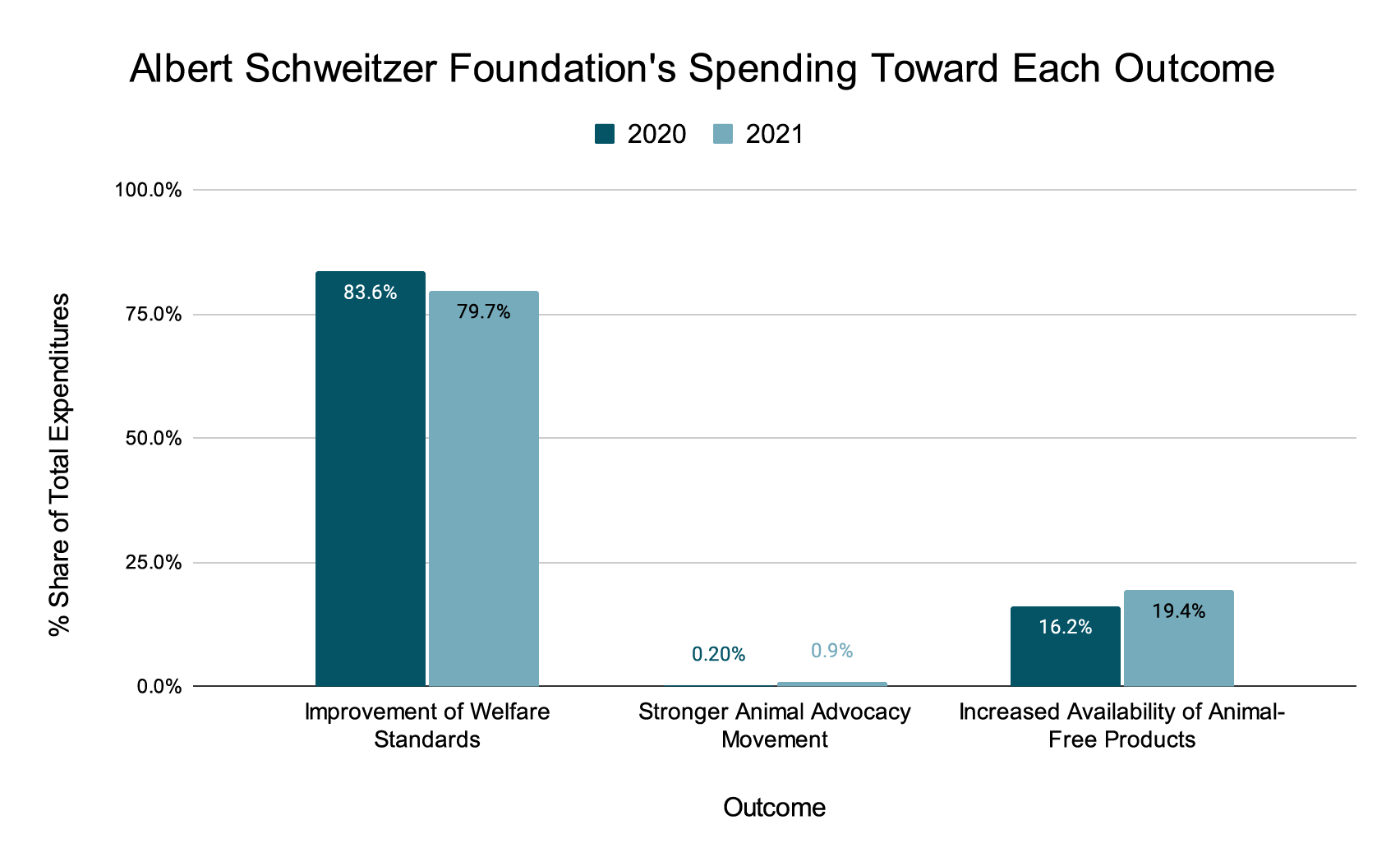

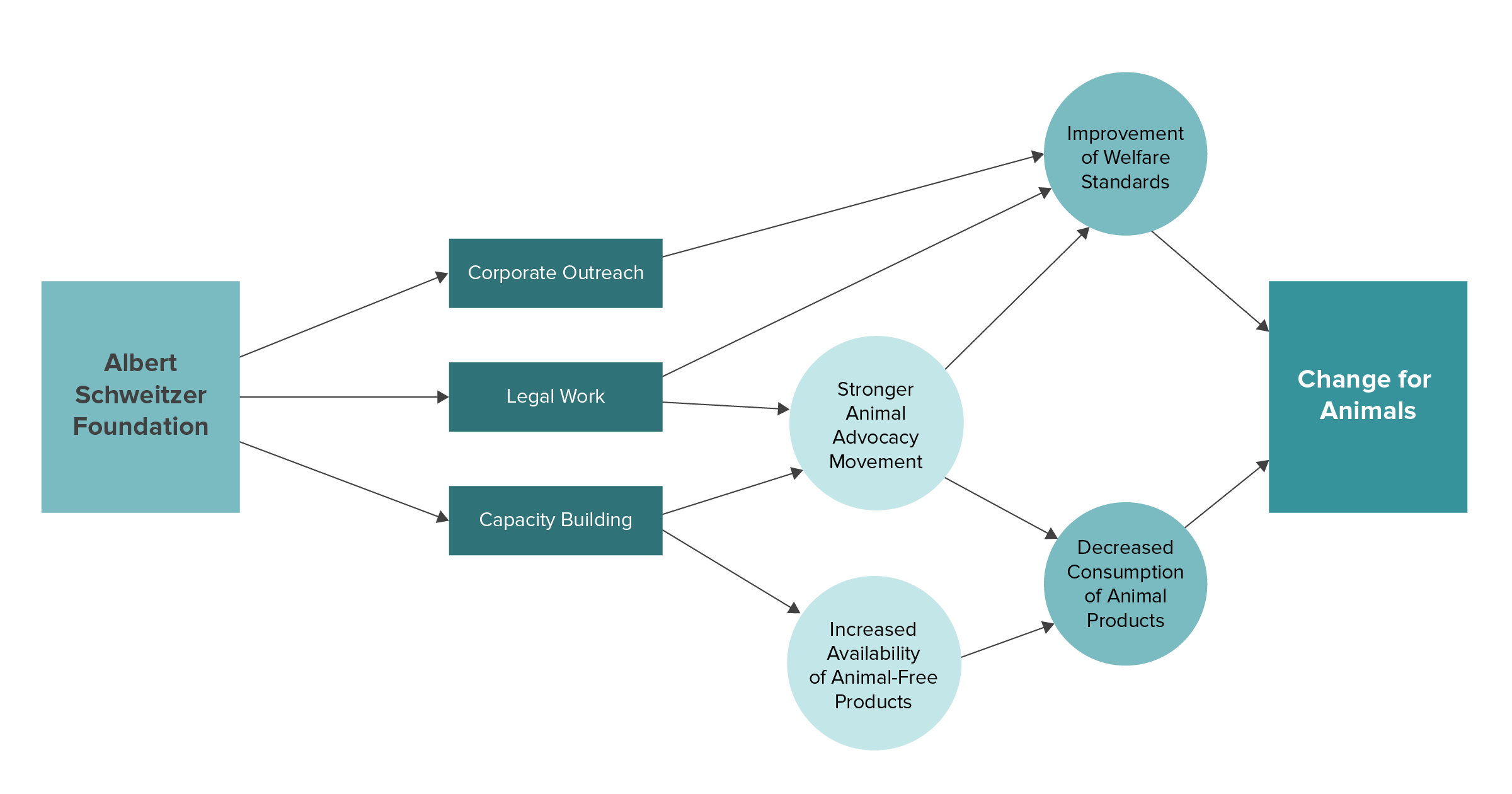

ASF pursues different avenues to create change for animals. Their work focuses on improving welfare standards, and to a lesser extent, also aims to strengthen the animal advocacy movement and increase the availability of animal-free products.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

Below, we describe each of ASF’s programs, listed in order of the financial resources devoted to them in 2020 (from highest to lowest). We list major accomplishments for each program, if a track record is available.

ASF’s programs

➤ Program 1: Corporate work (since 2008)

This program focuses on reaching out to companies in Germany and Poland to adopt policies that improve the welfare standards for farmed animals, especially egg-laying hens (change to cage-free housing systems), broiler chickens11 and fishes.

Main interventions

- Corporate outreach

Key historical accomplishments

- Achieved, in collaboration with other organizations and individuals, multiple corporate cage-free commitments in a large share of the German food industry

- Ended the practice of debeaking egg-laying hens in Germany and for international producers supplying to German retailers (2010–2015)

- Launched the Aquaculture Welfare Initiative with the support of German retailers (2018)

This program focuses on enforcing and changing laws in Germany to improve the welfare standards of farmed animals, especially egg-laying hens, broiler chickens, turkeys, dairy cows, pigs, and lobsters. In particular, this program aims to achieve verdicts that confirm that common practices in factory farming (e.g., selective breeding for high growth rates) violate German animal welfare law.

Main interventions

- Lawsuits

- Legal requests

Key historical accomplishments

- Successfully defended a court case in Germany on the legality of undercover investigations when animal welfare law is broken (2018)

- In cooperation with other organizations, won a campaign against plans to reopen a factory farm of pigs in Germany (2020)

- Campaigned against male chick culling, influencing the Federal Administrative Court to rule that the culling of male chicks is against the law (2019)

- Filed a lawsuit against the German Ministry of Agriculture, getting access to documents on male chick culling and the scientific method to determine chick sexes (2020)

This program focuses on creating changes in German and E.U. legislation, such as banning male chick culling and securing commitments to higher-welfare broiler chicken breeds, to improve the welfare standards of farmed animals. Most large German retailers have committed to selling 100% “higher-welfare” meat by 2030—ASF is especially focused on achieving high welfare standards for farmed animals through their legislative work during this window of opportunity.

Main interventions

- Petitions, (open) letters, and dialogues with lawmakers

- Participation in protests and demonstrations

- Advice on drafting legislation

Key historical accomplishments

- Influenced the introduction of a law that gives animal advocacy organizations in the federal state of Berlin the right to sue on behalf of animals (2017–2020)

- Influenced a wording correction of the official German translation of the E.U. pig directive (2008/120/EC) (2016) from specifying that their lying area should be “adequate” to “comfortable”, which will lead to changes in national laws

This program aims to help the international animal advocacy movement become more effective.

Main interventions

- Publication of whitepapers

- Participation in coalition initiatives

Key historical accomplishments

- Published a whitepaper on animal product reduction (2020)

- Became a member of OWA Advisory committee (2018–2021)

- Participated in the FAST Mentorship program (2021)

- Developed an online tool for ranking supermarkets according to their vegan options (2020)

Research for intervention effectiveness

Corporate outreach

There is some evidence that corporate outreach leads food companies to change their practices related to hen welfare. Šimčikas12 found that the follow-through rate of cage-free corporate commitments ranges from 48–84%. Cost-effectiveness estimates vary widely, and it is unclear which is the most accurate. Šimčikas estimates that corporate campaigns affect nine to 120 hen-years (i.e., years of chicken life) per dollar spent.

ASF currently prioritizes cage-free egg, broiler chicken, and fish welfare commitments. Cage-free housing systems are believed to reduce suffering by increasing the space available to egg-laying hens and providing them opportunities to perform important behaviors, although mortality may increase during the transition process, and there is some risk that it may remain elevated.13

ASF also campaigns for companies to switch to higher-welfare (but likely slower-growing) breeds of broiler chickens and to commit14 to provisions on stocking density, lighting, and environmental enrichments. Such commitments may lead to higher welfare but also to more animal days lived in factory farms.15

We think that improving farmed fish welfare is a particularly promising cause area due to the current neglectedness of the issue, the likelihood that farmed fish suffering is large in scale, and the potential tractability of interventions to improve farmed fish welfare.

Legal outreach and campaigns

ASF also works on legal and legislative advocacy. We are not confident about the effectiveness of legal outreach because there is currently a lack of research on this topic.16 However, we suspect that the effects of legal change could be particularly long-lasting, despite the long time frame compared to other forms of change. We also think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to impact a large number of animals.

Our Assessment

We think that ASF’s corporate outreach aimed at improving the welfare standards of farmed animals is particularly effective. There is some evidence supporting this claim, as studies suggest that corporate outreach to secure chicken commitments can impact a large number of animals. Despite the lack of evidence for the effectiveness of legal advocacy, we believe that ASF’s legal work has the potential to affect a large number of animals. Additionally, we think that ASF’s programs’ focus on helping numerous and neglected animal groups—such as farmed chickens, fishes, and lobsters—increases their effectiveness.

We consider ASF’s work in Germany and Poland to be particularly effective based on the high level of tractability and global influence in Germany and the small number of other organizations in Poland.

Overall, we think that almost all of ASF’s spending on programs goes toward increasing welfare standards and helping species that we think are a high priority.

Room for More Funding

A new recommendation from ACE could lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding. In this criterion, we investigate whether a charity is able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in or, if the charity has a prior recommendation status, whether they will continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation.

Method

In the following section, we inspect the charity’s plans for expansion as well as their financials, including revenue and expenditure projections.

The charities we evaluate typically receive revenue from a variety of different sources, such as individual donations or grants from foundations.17 In order to guarantee that a charity will raise the funds needed for their operations, they should be able to predict changes in future revenue. To estimate charities’ room for more funding, we request records of their revenue since 2019 and ask what they predict their revenue will be in 2021–2023. A review of the literature on nonprofit finance suggests that revenue diversity may be positively associated with revenue predictability if the sources of income are largely uncorrelated.18 However, a few sources of large donations—if stable and reliable—may also be associated with high performance and growth. Therefore, in this criterion, we also indicate the charities’ major sources of income.

We present the charities’ reported plans for expansion of each program as well as other planned changes for the next two years. We do not make active suggestions for additional plans. However, we ask charities to indicate how they would spend additional funding that we expect would come in as a result of a new recommendation from ACE, considering that a Standout Charity status and a Top Charity status would likely lead to a $100,000 or $1,000,000 increase in funding, respectively. Note that we list the expenditures for planned non-program expenses but do not make any assessment of the charity’s overhead costs in this criterion, given that there is no evidence that the total share of overhead costs is negatively related to overall effectiveness.19 However, we do consider relative overhead costs per program in our Cost-Effectiveness criterion. Here we focus on evaluating whether additional resources are likely to be used for effective programs or other beneficial changes in the organization. The latter may include investments into infrastructure and efforts to retain staff, both of which we think are important for sustainable growth.

It is common practice for charities to hold more funds than needed for their current expenses (i.e., reserves) in order to be able to withstand changes in the business cycle or other external shocks that may affect their incoming revenue. Such additional funds can also serve as investments into future projects in the long run. Thus, it can be effective to provide a charity with additional funds to secure the stability of the organization or provide funding for larger, future projects. We do not prescribe a certain share of reserves, but we suggest that charities hold reserves equal to at least one year of expenditures, and we increase a charity’s room for more funding if their reserves in 2021 are less than 100% of their total expenditure.

Finally, we aggregate the financial information and the charity’s plans to form an assessment of their room for more funding. All descriptive data and estimations can be found in this sheet. Our assessment of a charity’s ability to effectively absorb additional funding helps inform our recommendation decision.

Information and Analysis

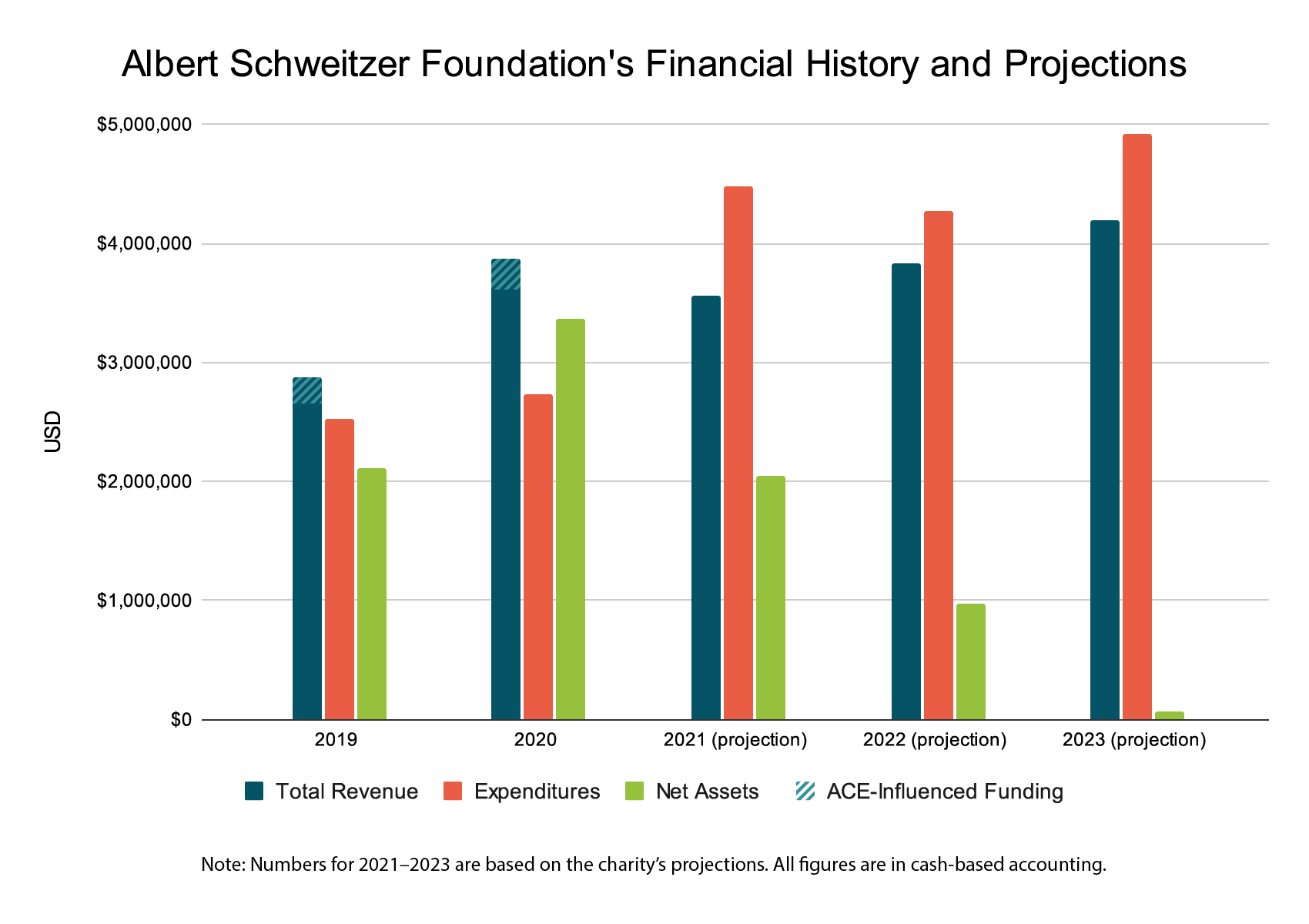

The chart below shows ASF’s revenues, expenditures, and net assets from 2019–2020, as well as projections for the years 2021–2023. The information is based on the charity’s past financial data and their own predictions for the years 2021–2023.

ASF receives the majority of their income from donations and less than 1% from their own work and capital investments combined.20 In 2020, they received 19.4% of their funding from a single donation.

ASF has also received funding influenced by ACE as a result of their prior recommended charity status for the past seven years. As such, their room for more funding analysis will focus on our assessment of whether they will continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation.

According to ASF’s reported projections, their estimated revenue in 2022 will not cover their expenditures. Subtracting their projected annual revenue from their projected annual expenditures, we find a funding gap of about $441,000 in 2022 and about $727,000 in 2023.21 We estimate that ASF has received $221,000 in 2019 and $263,000 in 2020 as a result of their prior recommended charity status; should ASF lose their recommended charity status, their projected revenue may be lowered, resulting in more room for funding.

With about 45.7% of their current annual expenditures held in net assets—as projected by ASF for 2021—we believe that they could benefit from holding a larger amount of reserves. As such, we add additional funding to replenish their reserves to the charity’s plans for expansion.

Below we list ASF’s plans for expansion for each of their programs as well as other planned expenditures, such as administrative costs, wages, and training. We do not verify the feasibility of the plans or the specifics of how changes in expenditure will cover planned expansions. Reported changes in expenditure are based on the charity’s own estimates of change in expenditures of the program from 2021–2022 and 2022–2023.

ASF plans to expand their corporate work, legal work, and legislative work/lobbying. More details can be found in the corresponding estimation sheet and the supplementary materials. Readers may also consult ASF’s Transparency and Effectiveness report.

- Potentially hire one to two new team members to work on animal product reduction

- Hire two new team members for Poland

- Grow aquaculture work

- Conduct more broiler campaigns

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: -$449,00022

- 2023: $351,000

- Work with external animal protection law lawyers

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $51,000

- 2023: $196,000

- Hie one to two new team members to work with the new German government

- Work with external experts

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $52,000

- 2023: $48,000

- No changes

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $3,000

- 2023: $3,000

- Expand to Austria and Switzerland; hire one new team member to work from Germany to facilitate this

- Expand to Romania; hire four new team members for this country and one new team member for support

- External training on conflict resolution

Estimate of expenditure

- 2022: $136,000

- 2023: $43,000

- 2022: $2,435,000

- 2023: $3,302,000

Our Assessment

ASF plans to focus future expansions on their corporate work, legal work, and legislative work/lobbying. For donors influenced by ACE wishing to donate to ASF, we estimate that the organization can continue to effectively absorb funding that we expect to come with a recommendation status.

Based on i) ASF’s own projections that their projected revenue will not cover their expenditures, ii) our assessment that they can use additional reserves, and iii) our assumption that a loss of recommendation status would result into a decrease in funding, we believe that overall, ASF continues to have room for $3,118,000 of additional funding in 2022 and $4,271,000 in 2023. See our Programs criterion for our assessment of the effectiveness of their programs.

It is possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or that they could come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. If a charity receives a recommendation as Top Charity, we check in mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented above to indicate whether we still expect them to be able to effectively absorb additional funding at that time.

Cost Effectiveness

Method

A charity’s recent cost effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component in understanding how cost effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources over the past 18 months and compare that to the outputs they have achieved in each of their main programs during that time. We seek to understand whether each charity has been successful at implementing their programs in the recent past and whether past successes were achieved at a reasonable cost. We only complete an assessment of cost effectiveness for programs that started in 2019 or earlier and that have expenditures totaling at least 10% of the organization’s annual budget.

Below, we report what we believe to be the key outputs of each program, as well as the total program expenditures. To estimate total program expenditures, we take the reported expenditures for each program and add a portion of their non-program expenditures weighted by the size of the program. This allows us to incorporate general organizational running costs into our consideration of cost effectiveness.

We spend a significant portion of our time during the evaluation process verifying the outputs charities report to us. We do this by (i) searching for independent sources that can help us verify claims, and (ii) directing follow-up questions to charities to gather more information. We adjusted some of the reported claims based on our verification work.

Information and Analysis

Overview of expenditures

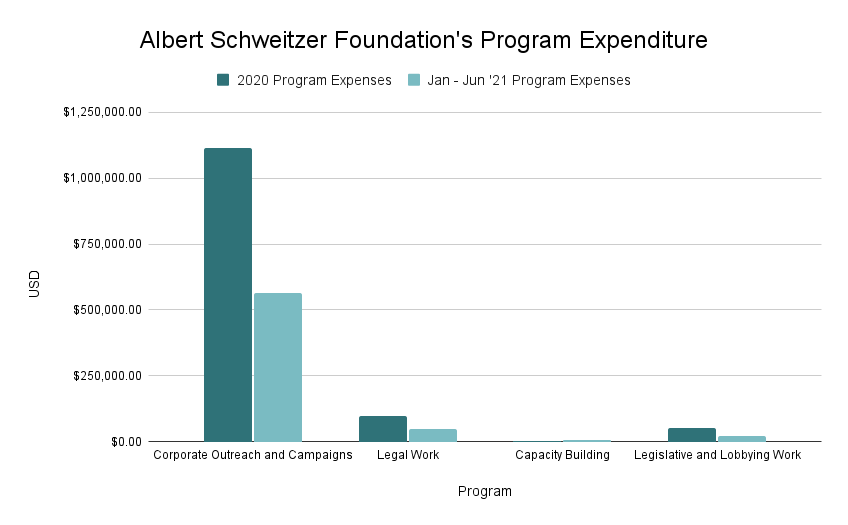

The following chart shows ASF’s total program expenditures from January 2020 – June 2021.23

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Continued to push retailers to eliminate the sale of live fish and published “Recommendations on Animal Welfare in Aquaculture”, which all members of the Aquaculture Welfare Initiative have now signed

- Convinced Domino’s Pizza to commit to raising its animal welfare standards for broiler chickens in six European countries (alongside Compassion In World Farming)

- Secured 28 European Chicken Commitment commitments (alone and in cooperation with other groups)

- Secured seven cage-free commitments (alone and in cooperation with other groups)

- Influenced the development of three commitments to improve the welfare of broiler chickens, pigs, turkeys and cattle (alone and in cooperation with other groups)

Expenditures24 (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $2,758,000

ASF’s corporate outreach and corporate campaigns programs focus on securing commitments to improve welfare standards for farmed animals. This work generally seeks to make incremental improvements to the conditions in which animals live, e.g., in factory farms. For farmed animals, welfare reforms generally only result in small improvements to their living conditions. However, this is balanced by the large numbers of animals who can be impacted, and there is some evidence to suggest that farmed animal welfare reforms are likely to be very cost effective in the short term.25 In general, we expect a focus on chickens and fishes to be the most cost effective, as they are among the most numerous groups of farmed animals.

There is some evidence that corporate outreach leads food companies to change their practices related to hen welfare. Šimčikas26 found that the follow-through rate of cage-free corporate commitments ranges from 48–84% and that corporate campaigns affect nine to 120 hen-years per dollar spent. We are not aware whether ASF actively follows up on whether companies follow through on their welfare commitments; however, ASF secured a share of their cage-free commitments in Germany, where it seems that companies prefer to implement cage-free commitments very quickly, often prior to announcing them. This is a distinct advantage over the U.S., for example, where companies have made commitments with implementation deadlines of 5–10 years, creating a risk that they will not be followed through on without continued campaigning.27

ASF also organizes the Aquaculture Welfare Initiative. All 34 members of the initiative—including producers, retailers, certifiers, and science/government agencies—have signed in agreement to ASF’s document “Recommendations for Animal Welfare in Aquaculture”, which specifies conditions for improving fish welfare. The recommendations also cover shrimps, which are among one of the most numerous groups of farmed animals; thus, the successful implementation of the recommendations could potentially improve the welfare of billions of animals per year. As fishes are currently one of the most neglected and largest farmed animal groups, it may be that their work in this area is particularly cost effective in comparison to corporate campaigns targeting other animal groups.

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Was granted the right to file lawsuits on behalf of animals by the Berlin Senate Department for Justice, Consumer Protection and Anti-Discrimination

- Provided strategic assistance and financial support that contributed to the success of a legal case against reopening a mega-pig farm

- Received access to documents on chicken sexing (a scientific method to determine the sexes of chicks) after organizing a petition and ultimately suing the German Ministry of Agriculture to gain access

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $240,473.00

ASF’s legal work program focuses on improving welfare standards for farmed animals by fighting for changes to German national law. We think it is likely that the most cost-effective work is focused on system-wide change to national law that, although harder to secure, has the potential to affect a larger number of animals. However, we are still particularly uncertain about the cost effectiveness of this work, given that the outcomes for animals are relatively indirect and that the majority of the potential impact may be in the future.

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Contributed to partially ending the use of sow cages in Germany by co-organizing a petition and co-writing a report with 11 other organizations

- Successfully lobbied, together with Erna-Graff-Stiftung, for the introduction of a law that enables recognized animal protection groups to sue on behalf of animals in the Federal State of Berlin

- Co-authored a position paper on animal transportation aimed at increasing pressure to ban live transport to non-European countries

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $120,000

ASF’s legislative and lobbying program focuses on improving farmed animal welfare standards by using petitions and lobbying tactics to persuade German politicians to make meaningful change. The majority of their results are indirect and achieved in cooperation with other groups, and as such, it is difficult to assess their cost effectiveness. In legal and political advocacy, we think it is likely that the most cost-effective work is focused on system-wide change that, although harder to secure, has the potential to affect a larger number of animals.

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Wrote a whitepaper on animal product reduction work, providing information on the current best practices

- Developed and openly shared an online tool for ranking supermarkets by their vegan-friendliness, which has already been used by 10 organizations in 10 different countries

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $13,573.00

ASF’s capacity-building program focuses on developing and sharing knowledge and resources, and providing professional training to other charities. This strategy of sharing knowledge allows ASF’s successful corporate campaigning model to be spread internationally without the need for their own expansion, and it seems to be particularly cost effective. As so few resources have gone into the program, we are particularly uncertain about its cost effectiveness and thus have not included any further assessment.

Our Assessment

The impacts of ASF’s legal work, legislative work, and lobbying program on animals are more indirect and may happen in the future; as such, the cost effectiveness is difficult to assess using our methods. Given the outputs achieved using the stated expenditures per program, we do not have concerns about the cost effectiveness of ASF’s programs.

Leadership and Culture

A charity that performs well on this criterion has strong leadership and a healthy organizational culture. The way an organization is led affects its organizational culture, which in turn impacts the organization’s effectiveness and stability.28 The key aspects that ACE considers when examining leadership and culture are reviewed in detail below.

Method

We review aspects of organizational leadership and culture by capturing staff and volunteer perspectives via our culture survey, in addition to information provided by top leadership staff (as defined by each charity).

Assessing leadership

First, we consider key information about the composition of leadership staff and board of directors. There appears to be no consensus in the literature on the specifics of the relationship between board composition and organizational performance,29 therefore we refrain from making judgements on board composition. However, because donors may have preferences on whether the Executive Director (ED) or other top executive staff are board members or not, we note when this is the case. According to the Council on Foundations,30 risks of EDs serving as board members include conflicts of interest when the board sets the ED’s salary, complicated reporting relationships, and blurred lines between governing bodies and staff. On the other hand, an ED that is part of a governing board can provide context about day-to-day operations and ultimately lead to better informed decisions, while also giving the ED more credibility and authority.31

We also consider information about leadership’s commitment to transparency by looking at available information on the charity’s website, such as key staff members, financial information, and board meeting notes. We require organizations selected for evaluation to be transparent with ACE throughout the process. Although we value transparency, we do not expect all organizations to be transparent with the public about sensitive information. For example, we recognize that organizations and individuals working in some regions or on some interventions could be harmed by making information about their work public. In these cases, we favor confidentiality over transparency.

In addition, we utilize our culture survey to ask staff to identify the extent to which they feel that leadership is competently guiding the organization.

Organizational policies

We ask organizations undergoing evaluation to provide a list of their human resources policies, and we elicit the views of staff and volunteers through our culture survey. Administering ACE’s culture survey to all staff members, as well as volunteers working at least 20 hours per month, is an eligibility requirement to be recommended as an ACE Top or Standout Charity. However, ACE does not require individual staff members or volunteers at participating charities to complete the survey. We recognize that surveying staff and volunteers could (i) lead to inaccuracies due to selection bias, and (ii) may not reflect employees’ true opinions as they are aware that their responses could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer. In our experience, it is easier to uncover issues with an organization’s culture than it is to assess how strong an organization’s culture is. Therefore, we focus on determining whether there are issues in the organization’s culture that have a negative impact on staff productivity and well-being.

We assume that employees in the nonprofit sector have incentives that are material, purposive, and solidary.32 Since nonprofit sector wages are typically below for-profit wages, our survey elicits wage satisfaction from all staff. Additionally, we request the organization’s benefit policies regarding time off, health care, and training and professional development. As policies vary across countries and cultures, we do not evaluate charities based on their set of policies and do not expect effective charities to have all policies in place.

To capture whether the organization also provides non-material incentives, e.g., goal-related intangible rewards, we elicit employee engagement using the Gallup Q12 survey. We consider an average engagement score below the median value (i.e., below four) of the scale a potential concern.

ACE believes that the animal advocacy movement should be safe and inclusive for everyone. Therefore, we also collect information about policies and activities regarding representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI). We use the terms “representation” and “diversity” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of certain social identity characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries).33 Additionally, we believe that effective charities must have human resources policies against harassment34 and discrimination,35 and that cases of harrassment and discrimination in the workplace should be addressed appropriately. If a specific case of harassment or discrimination from the last 12 months is reported to ACE by several current or former staff members or volunteers at a charity, and said case remains unaddressed, the charity in question is ineligible to receive a recommendation from ACE.

Information and Analysis

Leadership staff

In this section, we list each charity’s President (or equivalent) and/or Executive Director (or equivalent), and we describe the board of directors. This is completed for the purpose of transparency and to identify the relationship between the ED and board of directors.

- President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO): Mahi Klosterhalfen, involved in the organization for 13 years

- Number of members on board of directors: three members, including President and CEO Mahi Klosterhalfen

ASF did not have a transition in leadership in the last year.

About 71% of staff respondents to our culture survey at least somewhat agreed that ASF’s leadership team guides the organization competently, while about 18% at least somewhat disagreed, and 11% neither agreed nor disagreed.

ASF has been transparent with ACE during the evaluation process. In addition, ASF’s audited financial documents are available on the charity’s website or GuideStar. Lists of board members and key staff members are available on the charity’s website.

Culture

ASF has 39 staff members (including full-time, part-time, and contractors). We sent our survey to 34 staff members and 28 responded, yielding a response rate of 82%. We only survey volunteers who work at least 20 hours per month, and ASF reports they have none.

ASF has a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. Of the staff members that responded to our survey, about 4% report that they are at least somewhat dissatisfied with their wage. ASF offers 26 days of paid time off per year, unlimited sick days, and full healthcare coverage. All staff members report that they are at least somewhat satisfied with the benefits provided. Additional policies are listed in the table below.

General compensation policies

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A formal compensation policy to determine staff salaries | |

| Paid time off

In Germany: 26 paid days off (legal minimum is 20 days) In Poland: 26 paid days off (legal minimum is 26 days) |

|

| Sick days and personal leave

No limit on sick days (in accordance with German law) |

|

| Healthcare coverage

Health care plans are mandatory under German law, and reimbursement covers most health care costs and all salaries. Health care plans are also mandatory under Polish law. Reimbursement covers most health care costs and all salaries. |

n/a |

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| Annual (or more frequent) performance evaluations | |

| Formal onboarding or orientation process | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Funding provided for books or other educational materials related to each employee’s work | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support | |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Remote work option | |

| Paid internships | |

| Paid trainings available on topics such as: diversity, leadership, and conflict resolution | |

| Paid trainings in intercultural competence |

The average score in our engagement survey is 5.8 (on a 1–7 scale), suggesting that on average, staff do not exhibit a low engagement score. ASF has staff policies against harassment and discrimination. A few staff members report that they themselves have experienced harassment or discrimination at their workplace during the last twelve months, while about a third report to have witnessed harassment or discrimination of others. Only one-tenth of these people agree that the situation was handled appropriately. See all other related policies in the table below.

ASF’s leadership reported that an informal complaint was made by three staff members. The board looked into the complaint and concluded it was not a discrimination issue. Based on feedback about how the informal complaint was handled, ASF decided to set up a new reporting mechanism, organize a mandatory training on the German anti-discrimination law for all staff members, and hire two coaches to resolve the remainders of the conflict.

Policies related to representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI)

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics/conduct | |

| A written statement that the organization does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels, up to and including the board of directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| Documentation of all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

Our Assessment

We are concerned that several staff reported that an instance of harrassment or discrimination at the organization was not handled appropriately. We do, however, positively note that ASF is taking clear steps to address this issue, is transparent toward external stakeholders, and that staff generally agree that leadership guides the organization competently.

On average, our team considers advocating for welfare improvements to be a positive and promising approach. However, there are different viewpoints within ACE’s research team on the effect of advocating for animal welfare standards on the spread of anti-speciesist values. There are concerns that arguing for welfare improvements may lead to complacency related to animal welfare and give the public an inconsistent message—e.g., see Wrenn (2012). In addition, there are concerns with the alliance between nonprofit organizations and the companies that are directly responsible for animal exploitation, as explored in Baur and Schmitz (2012).

The weightings used for calculating these country scores are scale (25%), tractability (55%), and regional influence (20%).

We don’t believe that the number of individuals is the only relevant characteristic for scale, and we don’t necessarily believe that groups of animals should be prioritized solely based on the scale of the problem, however, number of animals is one characteristic we use for prioritization.

We estimate there are 10 quintillion, or 1019, wild animals alive at any time, of whom we estimate at least 10 trillion are vertebrates. It’s notable that Rowe (2020) estimates that 100 trillion to 10 quadrillion (or 1014 to 1016) wild invertebrates are killed by agricultural pesticides annually.

Farmed invertebrates include, among other groups, honey bee workers (26.4 trillion used annually), cochineals (9.93 trillion killed annually), caterpillars used for silk (636 billion killed annually) Rowe (2020)

For a discussion on invertebrate sentience, see for example Waldhorn et al. (2019).

For arguments supporting the view that the most important consideration of our present actions should be their impact in the long term, see Greaves & MacAskill (2019) and Beckstead (2019).

ACE believes that language can have a powerful impact on worldview, so we avoid terms such as “broiler chicken,” “poultry,” “beef,” etc., whenever possible. “Broiler chicken,” in particular, defines these birds in terms of their purpose for human consumption as meat. This can contribute to a lack of awareness about the origins of animal products and could make it difficult for consumers to understand the effects of their food choices. That being said, many of the charities that ACE evaluates use this language for strategic reasons in their campaigns, so we will use the term “broiler chicken” when referring to chickens raised for meat for the sake of simplicity.

The European Chicken Commitment is a six-point pledge that requires food companies to improve welfare standards for all chickens in their supply chain by 2026

A notable example of research in this area is Dullaghan’s 2020 report Ways EU law might matter for farmed animals.

To be selected for evaluation, we require that a charity has a revenue of at least about $50,000 and faces no country-specific regulatory barriers to receiving money from ACE.

ASF notes that the expenses of corporate work in 2021 were higher than usual because they budgeted a very large broiler campaign for that year. We expect that this explains the decrease in expenditure between 2021 and 2022.

ASF notes that some of the non-program costs that we have included in the ASF’s program expenditure graphic corresponds to other smaller programs that are not mentioned in the review. One of these smaller programs is the Vegan Taste Week, whose expenditures were 78.785€ in 2020 and 42.912€ in the first six months of 2021.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness.

For more information, see Šimčikas (2019b) and Open Philanthropy (2019).

Clark and Wilson (1961), as cited in Rollag (n.d.)

Examples of such social identity characteristics are: race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, and genetic information.

Harassment can be non-sexual or sexual in nature: ACE defines non-sexual harassment as unwelcome conduct—including physical, verbal, and nonverbal behavior—that upsets, demeans, humiliates, intimidates, or threatens an individual or group. Harassment may occur in one incident or many. ACE defines sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances; requests for sexual favors; and other physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors of a sexual nature when (i) submission to such conduct is made explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment; (ii) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting the targeted individual; or (iii) such conduct has the purpose or effect of interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

ACE defines discrimination as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of or hostility toward an individual on the basis of certain characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries), such as race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, or genetic information.