The Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO)

Archived Review| Review Published: | 2021 |

Archived Version: 2021

What does FIAPO do?

Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO) is an Indian organization primarily dedicated to reducing the suffering of farmed animals. To a lesser extent, they also work to help companion animals and animals used for entertainment. Their work focuses on improving animal welfare standards, strengthening the animal advocacy movement, increasing the availability of animal-free products, influencing legislation change, and providing direct help and veterinary care to animals. They also run a veg*n pledge program to encourage individuals to decrease their consumption of animal products.

What are their strengths?

FIAPO’s programs primarily focus on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we think is a high-priority cause area due to the large number of animals involved. Their movement-building program in India seems to be highly impactful, and we believe it is particularly effective given the low number of comparable organizations in the country. FIAPO’s plans for expansion indicate that they would be able to effectively utilize an increase in funding.

What are their weaknesses?

We consider FIAPO’s programs that focus on companion animals, animals used for entertainment, and veterinary care to be lower-priority because of the relatively small number of animals involved. In addition, it is difficult for us to assess the effectiveness of some of DVA’s programs due to the small amount of resources allocated to them. Some staff members report dissatisfaction with the organization’s recent leadership transition, and we have concerns about some reports of alleged discrimination or harrassment that a few staff members believe were not handled appropriately.

Why did we recommend them?

We think that FIAPO’s work to reduce the suffering of farmed animals has the potential to increase welfare standards for a large number of animals. FIAPO seems to be a key driver of animal welfare movement-building in India—where farmed animal advocacy is currently neglected—and we believe their work to build and strengthen the capacity of the animal advocacy movement there could potentially increase the effectiveness of other projects and organizations.

We find FIAPO to be an excellent giving opportunity because of their strong programs aimed at improving animal welfare standards and strengthening the animal advocacy movement in relatively neglected regions.

FIAPO has been one of our Standout Charities since November 2019. They received a grant from ACE’s Effective Animal Advocacy Fund in April 2019.

Programs

A charity that performs well on this criterion has programs that we expect are highly effective in reducing the suffering of animals. The key aspects that ACE considers when examining a charity’s programs are reviewed in detail below.

Method

In this criterion, we assess the effectiveness of each of the charity’s programs by analyzing (i) the interventions each program uses, (ii) the outcomes those interventions work toward, (iii) the countries in which the program takes place, and (iv) the groups of animals the program affects. We use information supplied by the charity to provide a more detailed analysis of each of these four factors. Our assessment of each intervention is informed by our research briefs and other relevant research.

At the beginning of our evaluation process, we select charities that we believe have the most effective programs. This year, we considered a comprehensive list of animal advocacy charities that focus on improving the lives of farmed or wild animals. We selected farmed animal charities based on the outcomes they work toward, the regions they work in, and the specific animal group(s) their programs target. We don’t currently consider animal group(s) targeted as part of our evaluation for wild animal charities, as the number of charities working on the welfare of wild animals is very small.

Outcomes

We categorize the work of animal advocacy charities by their outcomes, broadly distinguishing whether interventions focus on individual or institutional change. Individual-focused interventions often involve decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Institutional change involves improving animal welfare standards, increasing the availability of animal-free products, or strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

We believe that changing individual habits and beliefs is difficult to achieve through individual outreach.Currently, we find the arguments for an institution-focused approach1 more compelling than individual-focused approaches. We believe that raising welfare standards increases animal welfare for a large number of animals in the short term2 and may contribute to transforming markets in the long run.3 Increasing the availability of animal-free foods, e.g., by bringing new, affordable products to the market or providing more plant-based menu options, can provide a convenient opportunity for people to choose more plant-based options. Moreover, we believe that efforts to strengthen the animal advocacy movement, e.g., by improving organizational effectiveness and building alliances, can support all other outcomes and may be relatively neglected.

Therefore, when considering charities to evaluate, we prioritize those that work to improve welfare standards, increase the availability of animal-free products, or strengthen the animal advocacy movement. We give lower priority to charities that focus on decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Charities selected for evaluation are sent a request for more in-depth information about their programs and the specific interventions they use. We then present and assess each of the charities’ programs. In line with our commitment to following empirical evidence and logical reasoning, we use existing research to inform our assessments and explain our thinking about the effectiveness of different interventions.

Countries

A charity’s countries and regions of operations can affect their work with regard to scale, neglectedness, and tractability. We prioritize charities in countries with relatively large animal agricultural industries, few other charities engaged in similar work, and in which animal advocacy is likely to be feasible and have a lasting impact. In our charity selection process, we used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI), which combines proxies for scale, tractability, and global influence to create country scores.4 To assess neglectedness, we used our own data on the number of organizations that we are aware of working in each country. Below we present these measures for the country that the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO) operates in.

Animal groups

We prioritize programs targeting specific groups of animals that are affected in large numbers5 and receive relatively little attention in animal advocacy. Of the 187 billion farmed vertebrate animals killed annually for food globally, 110 billion are farmed fishes and 66.6 billion are farmed chickens, making these impactful groups to focus on. There are at least 100 times as many wild vertebrates as there are farmed vertebrates.6 Given the large number of wild animals and the small number of organizations working on their welfare, we believe wild animal advocacy also has potential for high impact despite its lower tractability.

A note about long-term impact

Each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.7 The potential number of animals affected increases over time due to population growth and an accumulation of generations. Thus, we would expect that the long-term impacts of an action would likely affect more animals than the short-term impacts of the same action. Nevertheless, we are highly uncertain about the particular long-term effects of each intervention. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew toward overemphasizing short-term effects.

Information and Analysis

Cause areas

FIAPO’s programs focus primarily on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we think is a high-priority cause area.

FIAPO also works on helping companion animals and animals in entertainment. Because these cause areas are less neglected, we do not consider them to be a high priority.

Countries

FIAPO develops their programs in India and has no subsidiaries in other countries.

We used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI) with the suggested weightings of scale (25%), tractability, (55%) and influence (20%) to determine each country’s total FAOI score. We report this score along with the country’s global ranking from a total of 60 countries in the following format: FAOI score(global ranking). India has the following score and ranking: 33.42(4). According to the comprehensive list of charities we are aware of, there are about 724 farmed animal advocacy organizations, excluding sanctuaries, worldwide. From this list, we found 20 in India. We believe that farmed animal advocacy in India is high-priority due to the large scale and moderate tractability reflected in its FAOI score. It is also relatively neglected given the very large number of animals affected.

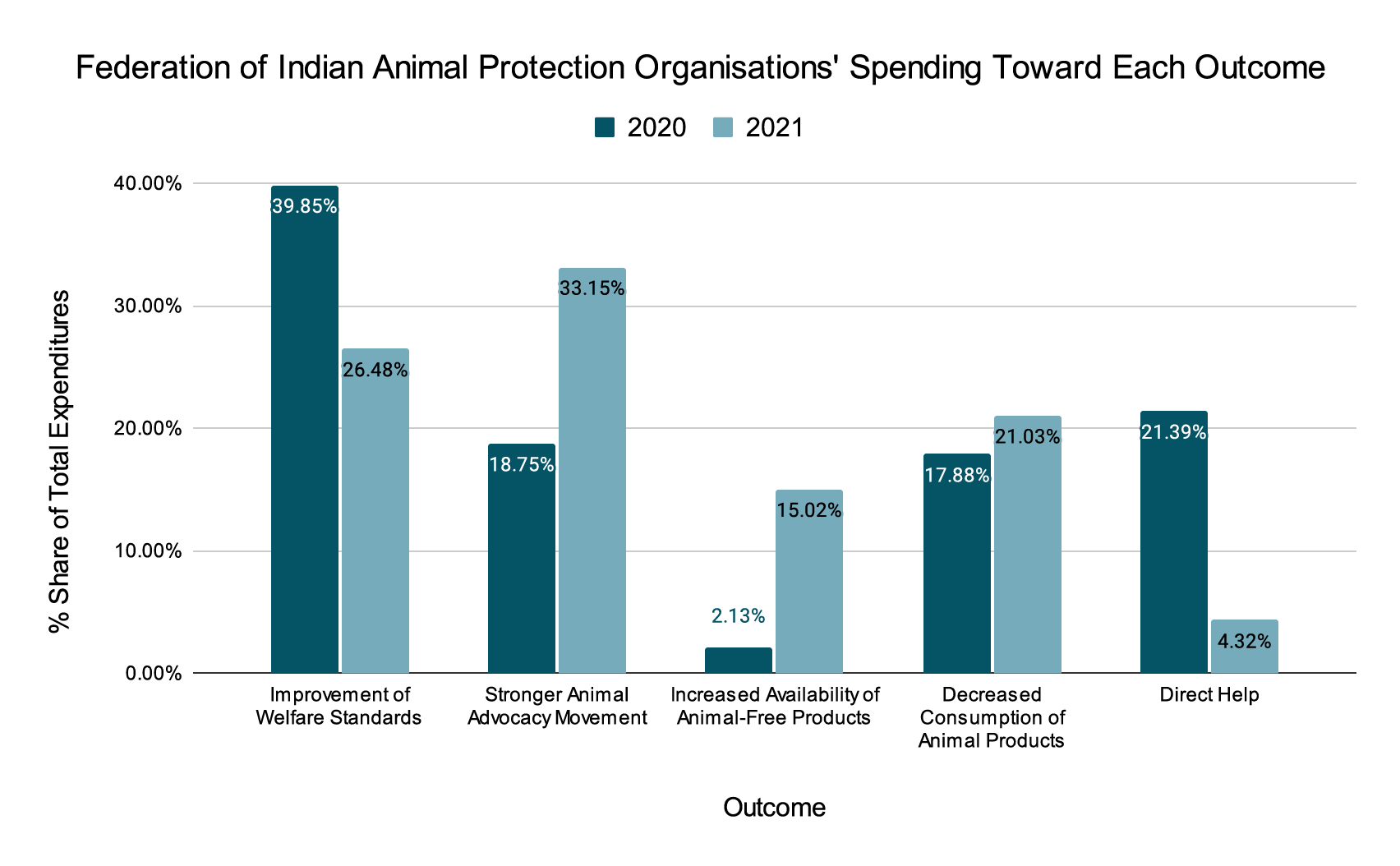

Description of programs

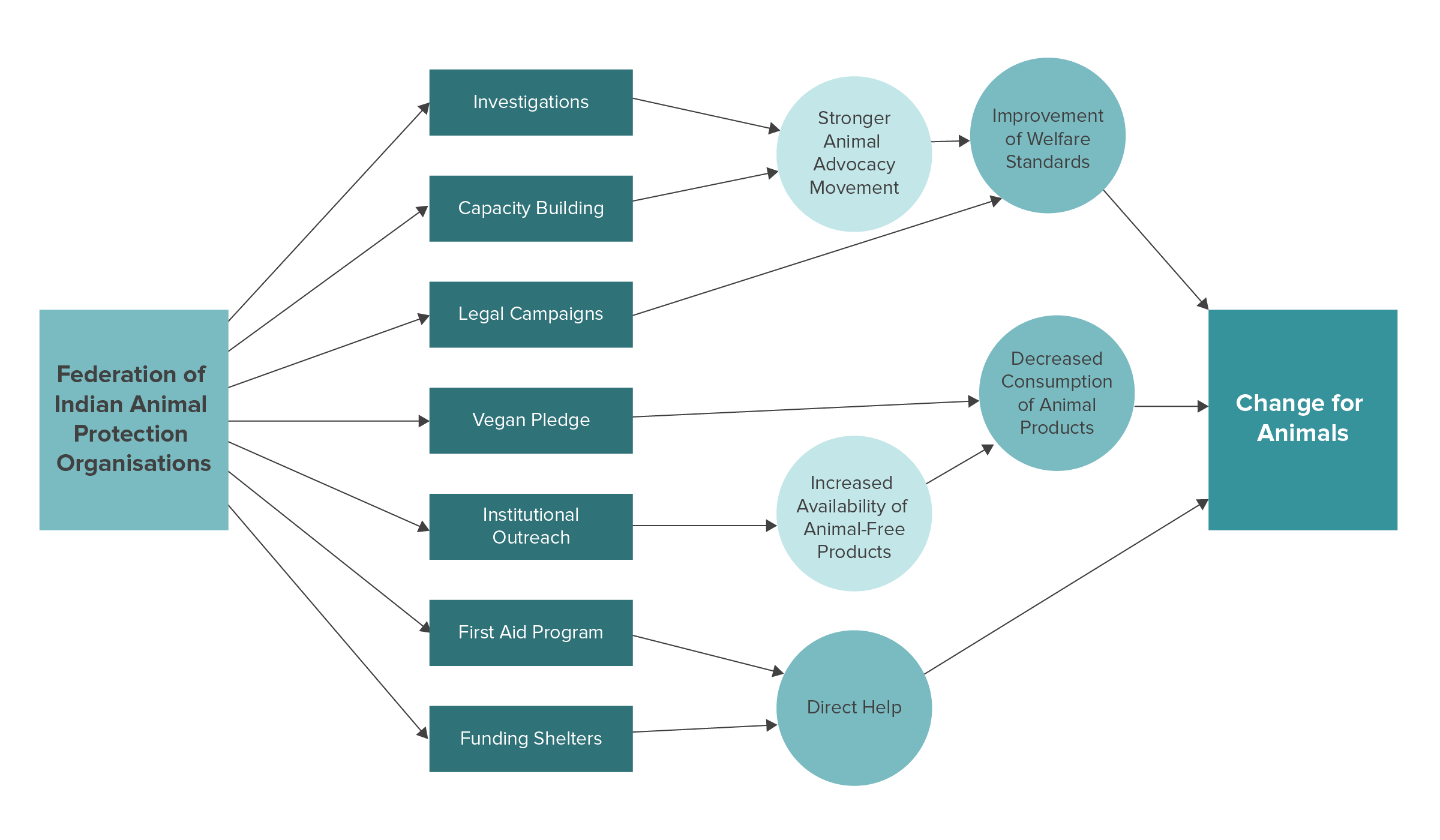

FIAPO pursues different avenues for creating change for animals. Their work focuses on improving welfare standards and strengthening the animal advocacy movement, and to a lesser extent also aims to increase the availability of animal-free products, decrease consumption of animal products, and provide direct help to animals.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

Below, we describe each of FIAPO’s programs, listed in order of the financial resources devoted to them in 2020 (from highest to lowest). We list major accomplishments for each program, if a track record is available.

FIAPO’s programs

This program focuses on creating legal change to improve the welfare of farmed cows in India, and influencing individuals and companies to decrease their consumption of animal products.

Main interventions

- Investigations

- Legal work

- Vegan pledge

Key historical accomplishments

- Helped stop the introduction of India’s first industrial dairy farm (2013)

- Submitted the “Gau Gatha” report to regulatory authorities in Uttar Pradesh, influencing the passage of voluntary welfare guidelines in gaushalas (i.e., protective shelters for cows; 2018–2019)

- Conducted an in-depth investigation into 500 dairy farms across the country, resulting in seven state governments introducing better welfare guidelines for dairy animals (2018–2019)

- Investigated 241 aquaculture farms in India (2020–2021)

- Created the 21 Day challenge to adopt a plant-based diet

- Ran a webinar with Eurogroup for Animals, resulting in recommendations for how the EU and India could work together to improve animal welfare in trade relations ahead of the EU–India trade summit (2021)

This program focuses on creating change for companion animals through running a first-aid program, providing grants to shelters, promoting responsible pet ownership, and conducting investigations into wild animal trade in India.

Main interventions

- Responsible pet ownership promotion

- Funding shelters

- First aid program

- Investigations

Key historical accomplishments

- Worked in three states to help local organizations start animal birth control, anti-rabies vaccination programs, and dog-bite prevention education in government schools

- Provided 213,100 meals to dogs and other street animals, in response to the need that arose during the first few months of the pandemic (2020)

- Created an awareness campaign to curb pet abandonment during the pandemic (2020–2021)

This program focuses on increasing the availability of animal-free products by providing resources to support businesses that are developing plant-based products in India.

Main interventions

- Institutional outreach

Key historical accomplishments

- Launched The Plant Factor Challenge to support startups in the plant-based food sector

- Launched the Plant Factor-y, a business directory that provides information on plant-based foods and personal care, fashion, and home products

This program focuses on creating legislative change to recognize the personhood of animals, as well as promoting the rescue and rehabilitation of urban wildlife by training volunteer rescue workers.

Main interventions

- Government outreach / legal campaigns

- Volunteer training

Key historical accomplishments

- Successfully campaigned to ban dolphinaria and the use of dolphins for entertainment in India

- Filed a petition in the Delhi High Court on behalf of circus animals, which contributed to the Animal Welfare Board canceling the registration of five circuses with over 100 animals (2020)

- Published a whitepaper on the behavioral needs of elephants in India to drive policy change for captive elephants (2020)

This program focuses on building the animal advocacy movement in India through membership recruitment and capacity-building of member organizations and individuals.

Main interventions

- Capacity building

- Membership recruitment

Key historical accomplishments

- Recruited 174 member organizations (as of 2021)

- Ran nine “Learn from Leaders” webinars, which had more than 770 attendees (2020)

- Mentored and trained 452 activists across India (2020)

Research for intervention effectiveness

Investigations

FIAPO conducts investigations into the animal agriculture industry, which can inform the public about practices in animal farms and serve as a resource for animal advocates. Currently, FIAPO’s main investigations involve the aquaculture industry—specific investigations are being conducted into water quality, the presence of heavy metals and antibiotics, stocking density, and the slaughter of small animals.

Legal work

FIAPO works on legal and legislative advocacy. While we are not confident about the effectiveness of legal work due to a lack of research on the topic, we suspect that the effects of legal change could be particularly long-lasting, despite the long time frame compared to other forms of change. We also think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to have an impact on a large number of animals.

FIAPO’s farmed animal work focuses on creating legal change for cows, which we think is unlikely to be as effective as focusing on chickens or fishes. That said, India has the largest population of cows in the world at an estimated 305 million in 2018, comparable to the country’s estimated 274 million broiler chickens.89 FIAPO reports that their new strategic plan—which kicks off in April 2022—will have a greater focus on pursuing legal change for fish, chicken, and small animals, in addition to cows.

Veg*n pledge program

FIAPO runs a veg*n pledge program. Some empirical studies suggest that self-monitoring—which is part of taking a veg*n pledge—reduces meat consumption, at least in the short run.10 Other studies that measure the impact of veg*n pledges suggest that some participants adopt a more plant-based diet for several months after the pledge.11 Besides dietary change, veg*n pledge programs may help recruit new people to the movement, normalize veg*nism, and raise awareness of veg*nism and animal-related issues.

Movement building

There is currently no empirical evidence that reviews the effectiveness of movement building in animal advocacy. However, we believe that capacity-building projects have the potential to help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Furthermore, building alliances with key influencers, institutions, or social movements could expand the audience and impact of animal advocacy organizations and projects, leading to net positive outcomes for animals. Additionally, ACE’s 2018 research and Harris12 suggest that capacity building and building alliances are currently neglected relative to other interventions aimed at influencing public opinion and industry.

Veterinary care

We currently do not prioritize veterinary care for companion animals because this intervention helps a smaller number of animals, is better funded, and is less neglected than interventions that help farmed animals or wild animals. We think this intervention can be used by charities for more indirect purposes, such as community and alliance-building, which can increase the effectiveness of this intervention.

Our Assessment

We think that FIAPO’s farmed animals program and movement building program—both aimed at improving the welfare standards of animals and strengthening the animal advocacy movement—are more effective than their other programs, but there is little evidence supporting this claim.

We consider FIAPO’s work in India to be particularly effective based on the very high number of animals and relatively low number of similar organizations in the country, as well as the moderate tractability reflected in its FAOI score.

Overall, we think that about half of FIAPO’s spending on programs goes toward outcomes, countries, and helping species that we think are a high priority.

Room for More Funding

A new recommendation from ACE could lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding. In this criterion, we investigate whether a charity is able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in or, if the charity has a prior recommendation status, whether they will continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation.

Method

In the following section, we inspect the charity’s plans for expansion as well as their financials, including revenue and expenditure projections.

The charities we evaluate typically receive revenue from a variety of different sources, such as individual donations or grants from foundations.13 In order to guarantee that a charity will raise the funds needed for their operations, they should be able to predict changes in future revenue. To estimate charities’ room for more funding, we request records of their revenue since 2019 and ask what they predict their revenue will be in 2021–2023. A review of the literature on nonprofit finance suggests that revenue diversity may be positively associated with revenue predictability if the sources of income are largely uncorrelated.14 However, a few sources of large donations—if stable and reliable—may also be associated with high performance and growth. Therefore, in this criterion, we also indicate the charities’ major sources of income.

We present the charities’ reported plans for expansion of each program as well as other planned changes for the next two years. We do not make active suggestions for additional plans. However, we ask charities to indicate how they would spend additional funding that we expect would come in as a result of a new recommendation from ACE, considering that a Standout Charity status and a Top Charity status would likely lead to a $100,000 or $1,000,000 increase in funding, respectively. Note that we list the expenditures for planned non-program expenses but do not make any assessment of the charity’s overhead costs in this criterion, given that there is no evidence that the total share of overhead costs is negatively related to overall effectiveness.15 However, we do consider relative overhead costs per program in our Cost Effectiveness criterion. Here we focus on evaluating whether additional resources are likely to be used for effective programs or other beneficial changes in the organization. The latter may include investments into infrastructure and efforts to retain staff, both of which we think are important for sustainable growth.

It is common practice for charities to hold more funds than needed for their current expenses (i.e., reserves) in order to be able to withstand changes in the business cycle or other external shocks that may affect their incoming revenue. Such additional funds can also serve as investments into future projects in the long run. Thus, it can be effective to provide a charity with additional funds to secure the stability of the organization or provide funding for larger, future projects. We do not prescribe a certain share of reserves, but we suggest that charities hold reserves equal to at least one year of expenditures, and we increase a charity’s room for more funding if their reserves in 2021 are less than 100% of their projected total expenditure.

Finally, we aggregate the financial information and the charity’s plans to form an assessment of their room for more funding. All descriptive data and estimations can be found in this sheet. Our assessment of a charity’s ability to effectively absorb additional funding helps inform our recommendation decision.

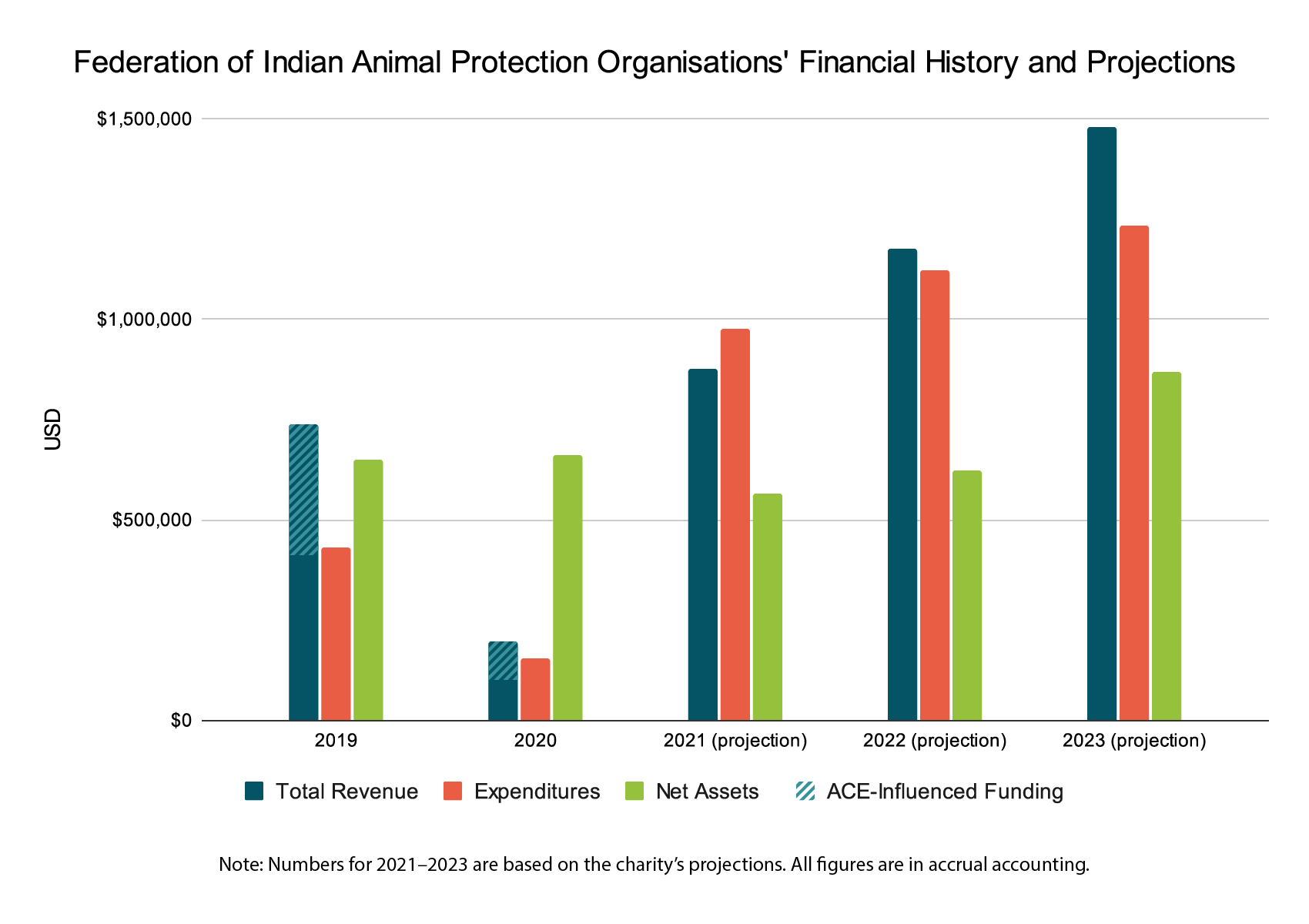

Information and Analysis

The chart below shows FIAPO’s revenues, expenditures, and net assets from 2019–2020, as well as projections for the years 2021–2023. The information is based on the charity’s past financial data and their own predictions for the years 2021–2023.

FIAPO receives the majority of their income from donations and 10.3% from their capital investments.16 They mentioned that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively and significantly affected their revenue in 2020 and 2021. During a considerable period in 2020, FIAPO could not receive foreign funding due to a delayed renewal of their FCRA license.

FIAPO has also received funding influenced by ACE as a result of their prior recommended charity status for the past two years. Thus, their room for more funding analysis will focus on our assessment of whether they could continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation or larger amounts of funding.

According to FIAPO’s reported projections, their estimated increase in revenue in 2022 will sufficiently cover their plans for expansion. We estimate that FIAPO has received $279,00017 in 2019 and $96,000 in 2020 as a result of their prior recommended charity status.18 Should FIAPO lose their recommended charity status, their projected revenue may be lowered, resulting in more room for funding.

FIAPO outlined that if they were to spend an additional $1,000,000 per year, it would be focused on pursuing investigations, litigation, and policy reform for farmed animals on a much larger scale; setting up a legal cell to offer support to FIAPO members; and developing a project, which has been started in collaboration with other organizations, to build the capacity of state-level Societies for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCAs). We believe that this is an effective use of funding, and that FIAPO could effectively absorb at least an additional $1,000,000 per year.

With about 58.04% of their current annual expenditures held in net assets—as reported by FIAPO for 2021—we believe that they could benefit from holding a larger amount of reserves. As such, we add additional funding to replenish their reserves to the charity’s plans for expansion.

Below we list FIAPO’s plans for expansion for each program as well as other planned expenditures, such as administrative costs, wages, and training. We do not verify the feasibility of the plans or the specifics of how changes in expenditure will cover planned expansions. Reported changes in expenditure are based on the charity’s own estimates of changes in program expenditures for 2021–2022 and 2022–2023.

FIAPO plans to expand their programs for farmed animals, companion animals, and animals in captivity, as well as their movement building and plant-based work. More details can be found in the corresponding estimation sheet and the supplementary materials. Readers may also consult FIAPO’s 2019 strategic plan.

- Expand their public awareness campaigns

- Increase digital outreach

- Resume in-person vegan advocacy (once COVID-19 restrictions lift)

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $40,000

- 2023: $44,000

- Resume the program (once COVID-19 restrictions lift)

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $5,000

- 2023: $6,000

- Expand outreach by collaboration with external experts

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: n/a19

- 2023: n/a

- Increase capacity by hiring lawyers

- File RTIs (Right to Information Act requests)

- Provide legal support to members

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $1,000

- 2023: $2,000

- Recruit farmed animal advocacy organizations (the majority of FIAPO’s current membership comprises companion animal organizations)

- Increase services provided to members, including legal services and a magazine

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $7,000

- 2023: $8,000

- Build the new FIAPO website into a resource for members and activists, with SOPs on legal matters (e.g., filing cases, RTIs, or public interest litigations), a directory of resources, and a helpline

- Set up of a physical office that had to be closed due to the pandemic

- Provide training for staff to build their networking capacity and expertise on specific issues and laws

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $93,000

- 2023: $53,000

- Increase investigations into the animal agriculture industry, including fish, cows and chickens

- Set up a legal cell

- Collaborate with other organizations to set up a national program to build the capacity of SPCAs in addressing animal cruelty

- Continue case-by-case litigation to free captive elephants

- 2022: $975,000

- 2023: $1,121,000

Our Assessment

FIAPO plans to expand their programs for farmed animals, companion animals, and animals in captivity, as well as their movement building and plant-based work. For donors influenced by ACE wishing to donate to FIAPO, we estimate that the organization can effectively absorb funding that we expect to come with a recommendation status.

Based on i) FIAPO’s own projections that their revenue will cover their expenditures, ii) our assessment that they can use additional reserves, iii) our assessment that they could effectively absorb an additional $1,000,000, and iv) our assumption that a loss of recommendation status would result in a decrease in funding, we believe that overall, FIAPO room for $2,107,000 of additional funding in 2022 and $2,062,000 of additional funding in 2023. See our Programs criterion for our assessment of the effectiveness of their programs.

It is possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or that they could come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. If a charity receives a recommendation as Top Charity, we check in mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented above to indicate whether we still expect them to be able to effectively absorb additional funding at that time.

Cost Effectiveness

Method

A charity’s recent cost effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component in understanding how cost effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources over the past 18 months and compare that to the outputs they have achieved in each of their main programs during that time. We seek to understand whether each charity has been successful at implementing their programs in the recent past and whether past successes were achieved at a reasonable cost. We only complete an assessment of cost effectiveness for programs that started in 2019 or earlier and that have expenditures totaling at least 10% of the organization’s annual budget.

Below, we report what we believe to be the key outputs of each program (for a complete list of outputs reported by FIAPO, see this document), as well as the total program expenditures. To estimate total program expenditures, we take the reported expenditures for each program and add a portion of their non-program expenditures weighted by the size of the program. This allows us to incorporate general organizational running costs into our consideration of cost effectiveness.

We spend a significant portion of our time during the evaluation process verifying the outputs charities report to us. We do this by (i) searching for independent sources that can help us verify claims, and (ii) directing follow-up questions to charities to gather more information. We adjusted some of the reported claims based on our verification work.

Information and Analysis

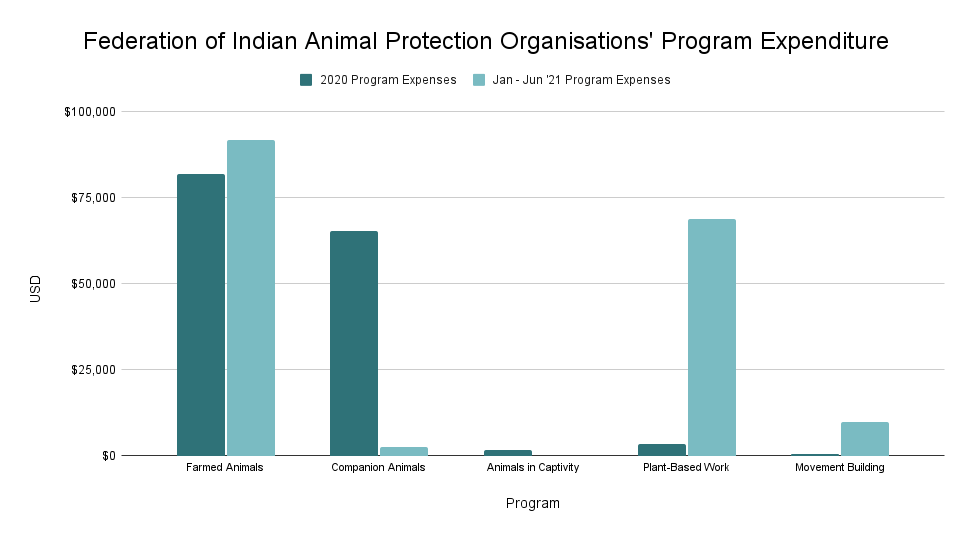

Overview of expenditures

The following chart shows FIAPO’s total program expenditures from January 2020 – June 2021.

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Completed undercover investigations of 22 dairy farms in Prayagraj and Varanasi, and followed up by filing a case in the Allahabad High Court to demand better conditions for the animals

- Compiled a report on illegal and unethical slaughter in unlicensed meat shops across seven cities, resulting in a directive for the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India to take action against illegal meat shops

- Conducted undercover investigations of 160 freshwater fish farms and 81 brackish water farms (in collaboration with other groups), making it India’s most in-depth investigation of such farms

- Persuaded the Department of Fisheries to be inclusive of animal welfare, environmental protection, and public health hazard elimination in he re-draft of the “National Fisheries Policy”

- Investigated 200 gaushalas (i.e., protective shelters for cows) to advocate for stricter policies, which resulted in the Uttar Pradesh government introducing welfare guidelines for all shelters

Expenditures20 (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $174,000

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Provided 213,100 meals to dogs and other street animals

- Created an awareness campaign to curb pet abandonment during the pandemic

- Engaged with the key government and regulatory authorities to form regulations against abandoning pet animals and feeding street animals during the pandemic

- Ran an emergency line for quick response to animal cruelty or distress and legal guidance during the pandemic

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $70,000

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Launched The Plant Factor challenge to drive innovation for better alternatives to animal products and support emerging business in the plant-based food sector (top three winners were awarded funding and access to experts in management, research, networking, funding, and mentorship)

- Supported India’s top eight plant-based businesses through a workshop series on business planning and investment

- Launched the Plant Factor-y, a business directory that provides information on plant based food and personal care, fashion, and home products

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $71,000

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Filed a petition in the Delhi High Court on behalf of circus animals, which contributed to the Animal Welfare Board canceling the registration of five circuses with over 100 animals (including the last circus in India that was using elephants for performances)

- Published a whitepaper on the behavioral needs of elephants in India to drive policy change for captive elephants

- Brought together organizations working for the welfare of captive elephants to respond to issues, produce in-depth research, and liaise with the government (the coalition took up the issue of elephants deaths in Kerala and Jaipur Hathigaon)

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $2,000

- Offered nine free “Learn from Leaders” webinars, which more than 770 activists attended

- Mentored and trained 452 budding activists across India

- Provided a series of 11 webinars that concentrated on issues pertaining to animal advocacy, which reached almost 5,000 people

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $10,000

Our Assessment

Given the reported outputs and expenditures, we do not have concerns about the cost effectiveness of FIAPO’s programs for farmed animals, plant-based work, and movement building. However, we are uncertain about the cost effectiveness of these programs, as the majority of their impacts are more indirect and/or may happen in the future.

We have some concerns about the cost effectiveness of FIAPO’s companion animals program. We do not consider companion animal welfare to be a high-priority cause area because it is relatively less neglected; however, we believe FIAPO may use this program as a way to educate and develop further animal advocacy in India.

As so few resources have gone into FIAPO’s animals in captivity program, we are particularly uncertain about its cost effectiveness and thus have not included any further assessment.

Leadership and Culture

A charity that performs well on this criterion has strong leadership and a healthy organizational culture. The way an organization is led affects its organizational culture, which in turn impacts the organization’s effectiveness and stability.21 The key aspects that ACE considers when examining leadership and culture are reviewed in detail below.

Method

We review aspects of organizational leadership and culture by capturing staff and volunteer perspectives via our culture survey, in addition to information provided by top leadership staff (as defined by each charity).

Assessing leadership

First, we consider key information about the composition of leadership staff and board of directors. There appears to be no consensus in the literature on the specifics of the relationship between board composition and organizational performance,22 therefore we refrain from making judgements on board composition. However, because donors may have preferences on whether the Executive Director (ED) or other top executive staff are board members or not, we note when this is the case. According to the Council on Foundations,23 risks of EDs serving as board members include conflicts of interest when the board sets the ED’s salary, complicated reporting relationships, and blurred lines between governing bodies and staff. On the other hand, an ED that is part of a governing board can provide context about day-to-day operations and ultimately lead to better-informed decisions, while also giving the ED more credibility and authority.

We also consider information about leadership’s commitment to transparency by looking at available information on the charity’s website, such as key staff members, financial information, and board meeting notes. We require organizations selected for evaluation to be transparent with ACE throughout the process. Although we value transparency, we do not expect all organizations to be transparent with the public about sensitive information. For example, we recognize that organizations and individuals working in some regions or on some interventions could be harmed by making information about their work public. In these cases, we favor confidentiality over transparency.

In addition, we utilize our culture survey to ask staff to identify the extent to which they feel that leadership is competently guiding the organization.

Organizational policies

We ask organizations undergoing evaluation to provide a list of their human resources policies, and we elicit the views of staff and volunteers through our culture survey. Administering ACE’s culture survey to all staff members, as well as volunteers working at least 20 hours per month, is an eligibility requirement to be recommended as an ACE Top or Standout Charity. However, ACE does not require individual staff members or volunteers at participating charities to complete the survey. We recognize that surveying staff and volunteers could (i) lead to inaccuracies due to selection bias, and (ii) may not reflect employees’ true opinions as they are aware that their responses could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer. In our experience, it is easier to assess issues with an organization’s culture than it is to assess how strong an organization’s culture is. Therefore, we focus on determining whether there are issues in the organization’s culture that have a negative impact on staff productivity and well-being.

We assume that employees in the nonprofit sector have incentives that are material, purposive, and solidary.24 Since nonprofit sector wages are typically below for-profit wages, our survey elicits wage satisfaction from all staff. We also ask organizations to provide volunteer hours, because due to the absence of a contract and pay, volunteering may be a special case of uncertain work conditions. Additionally, we request the organization’s benefit policies regarding time off, health care, and training and professional development. As policies vary across countries and cultures, we do not evaluate charities based on their set of policies and do not expect effective charities to have all policies in place.

To capture whether the organization also provides non-material incentives, e.g., goal-related intangible rewards, we elicit employee engagement using the Gallup Q12 survey. We consider an average engagement score below the median value (i.e., below four) of the scale a potential concern.

ACE believes that the animal advocacy movement should be safe and inclusive for everyone. Therefore, we also collect information about policies and activities regarding representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI). We use the terms “representation” and “diversity” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of certain social identity characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries).25 Additionally, we believe that effective charities must have human resources policies against harassment26 and discrimination,27 and that cases of harrassment and discrimination in the workplace should be addressed appropriately. If a specific case of harassment or discrimination from the last 12 months is reported to ACE by several current or former staff members or volunteers at a charity, and said case remains unaddressed, the charity in question is ineligible to receive a recommendation from ACE.

Information and Analysis

Leadership staff

In this section, we list each charity’s President (or equivalent) and/or Executive Director (or equivalent), and we describe the board of directors. This is completed for the purpose of transparency and to identify the relationship between the ED and board of directors.

- CEO: Bharati Ramachandran

- Number of members on board of directors: 21 members

FIAPO had a transition in leadership in the last year. The previous Executive Director, Varda Mehrota, left in June 2021. Vasanthi Vadi was appointed by the Board as Acting Executive Director, and the Board formed sub-committees to oversee the organization’s activities until a permanent Executive Director was appointed. In September 2021, Bharati Ramachandran was appointed as the new CEO.

About 56% of staff respondents to our culture survey at least somewhat agreed that FIAPO’s leadership team guides the organization competently, while about 31% at least somewhat disagreed, and 13% neither agreed nor disagreed.

FIAPO has been transparent with ACE during the evaluation process. In addition, FIAPO’s audited financial documents are available on the charity’s website. Lists of board members and trustees are also available on the charity’s website. A list of key staff members is not available.

Culture

FIAPO has 38 staff members (including full-time, part-time, and contractors) and 268 volunteers. Sixteen staff members (one email bounced) and seven volunteers (seven emails bounced) responded to our survey, yielding response rates of 43% and 2%, respectively.

FIAPO has a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. Of the staff members that responded to our survey, about 19% report that they are at least somewhat dissatisfied with their wage. FIAPO offers paid time off, sick days, and healthcare coverage. About 19% of staff report that they are at least somewhat dissatisfied with the benefits provided. Additional policies are listed in the table below.

General compensation policies

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A formal compensation policy to determine staff salaries | |

| Paid time off | |

| Sick days and personal leave | |

| Healthcare coverage | |

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| Annual (or more frequent) performance evaluations | |

| Formal onboarding or orientation process | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support | |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Remote work option | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) |

The average score in our engagement survey is 5.2 (on a 1–7 scale), suggesting that on average, staff do not exhibit a low engagement score. FIAPO has staff policies against harassment and discrimination. None of the staff members or volunteers report that they have experienced harassment or discrimination at their workplace during the last twelve months, while a few report to have witnessed harassment or discrimination of others. None of these people agree that the situation was handled appropriately. See all other related policies in the table below.

Policies related to representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI)

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics/conduct | |

| A written statement that the organization does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels, up to and including the board of directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| Documentation of all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances

FIAPO have let us know they are currently working on this policy |

Our Assessment

We did not detect any major concerns in FIAPO’s leadership and organizational culture. However, we noted some dissatisfaction with the leadership transition, and we are concerned that some staff believe that some instances of harrassment or discrimination were not handled appropriately. We positively noted that FIAPO’s team members seem generally engaged and satisfied with their job.

On average, our team considers advocating for welfare improvements to be a positive and promising approach. However, there are different viewpoints within ACE’s research team on the effect of advocating for animal welfare standards on the spread of anti-speciesist values. There are concerns that arguing for welfare improvements may lead to complacency related to animal welfare and give the public an inconsistent message—e.g., see Wrenn (2012). In addition, there are concerns with the alliance between nonprofit organizations and the companies that are directly responsible for animal exploitation, as explored in Baur and Schmitz (2012).

The weightings used for calculating these country scores are scale (25%), tractability (55%), and regional influence (20%).

We don’t believe that the number of individuals is the only relevant characteristic for scale, and we don’t necessarily believe that groups of animals should be prioritized solely based on the scale of the problem. However, number of animals is one characteristic we use for prioritization.

We estimate there are 10 quintillion, or 1019, wild animals alive at any time, of whom we estimate at least 10 trillion are vertebrates. It’s notable that Rowe (2020) estimates that 100 trillion to 10 quadrillion (or 1014 to 1016) wild invertebrates are killed by agricultural pesticides annually.

For arguments supporting the view that the most important consideration of our present actions should be their impact in the long term, see Greaves & MacAskill (2019) and Beckstead (2019).

ACE believes that language can have a powerful impact on worldview, so we avoid terms such as “broiler chicken,” “poultry,” “beef,” etc., whenever possible. “Broiler chicken,” in particular, defines these birds in terms of their purpose for human consumption as meat. This can contribute to a lack of awareness about the origins of animal products and could make it difficult for consumers to understand the effects of their food choices. That being said, many of the charities that ACE evaluates use this language for strategic reasons in their campaigns, so we will use the term “broiler chicken” when referring to chickens raised for meat for the sake of simplicity.

See the review of two such studies in Bianchi et al (2018).

To be selected for evaluation, we require that a charity has a revenue of at least about $50,000 and faces no country-specific regulatory barriers to receiving money from ACE.

Prior to being awarded their Standout Charity status, FIAPO received a Movement Grant of $50,000 in April 2019.

FIAPO did not provide projected program expenditures for 2021, 2022, and 2023 for this program.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness.

Clark and Wilson (1961), as cited in Rollag (n.d.)

Examples of such social identity characteristics are: race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, and genetic information.

Harassment can be non-sexual or sexual in nature: ACE defines non-sexual harassment as unwelcome conduct—including physical, verbal, and nonverbal behavior—that upsets, demeans, humiliates, intimidates, or threatens an individual or group. Harassment may occur in one incident or many. ACE defines sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances; requests for sexual favors; and other physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors of a sexual nature when (i) submission to such conduct is made explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment; (ii) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting the targeted individual; or (iii) such conduct has the purpose or effect of interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

ACE defines discrimination as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of or hostility toward an individual on the basis of certain characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries), such as race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, or genetic information.