Children’s Rights

This page contains archived content from our discontinued Social Movement Analysis project.

We no longer feel that this project represents the quality of our most current research. For more information, see our blog post.

Children’s Rights and the Movement Against Corporal Punishment

The successes and failures of the children’s rights movement can serve as lessons to animal advocates. It’s an example of advocacy on behalf of a disregarded group of persons, in which members of that group have not been the leading proponents. However, many proponents had previously been hit as children and so could speak of what it felt like in the first person. In some cases this does not appear to have been an influential form of advocacy, but it’s important to recognize this difference may have implications for advocacy techniques.

The analysis below is not enough to determine with precision everything animal advocates can learn from movements on behalf of children. However, the report shows that laws criminalizing violence towards a particular groups of persons does appear to decrease that behavior by means of communicating the new non-violent social norm. Changes in the law in one country may also spread worldwide, as we see in the case of Sweden criminalizing corporal punishment. These changes were also accompanied by less dramatic measures, like reducing the risk of accidents (and thus the perceived need to inflict corporal punishment on children), spreading empathy for children’s situation, and making legal changes easy to support.

Table of Contents

- Why should animal activists be interested in the children’s movement?

- Early violence against children

- The development of children’s rights in England

- Sweden—The ban of corporal punishment

- The effect of the law on behavior

- The impact of precedent-setting

- An investigation of activist activity in children’s rights—New Zealand

- What can animal activists learn?

- Further research

Why should animal activists be interested in the children’s movement?

The nonhuman animal rights movement is often analogized to human rights movements, and of these analogies the children’s rights movement seems particularly apt and under-studied.

Throughout most of human history children were not entitled to any formally recognized legal rights. The concept still receives little attention in many countries, conspicuously so in the United States.1 Like with other human liberation movements, children have long been considered property (in this case, of their caregivers). However, the emergence of children’s rights stands isolated among such human liberation movements, as one in which the beneficiaries were not the leading proponents- children are not in a position to campaign for themselves, limited in their ability to express their discontent in ways that adults recognize and don’t actively discount2 and possessing little power to resist physical assault. Exploited nonhuman animals are in a similar predicament today; unable to campaign, communicate effectively or resist harm, their interests are almost entirely ignored and property status maintained. The idea that they should be the beneficiaries of rights is often met with fierce opposition.

As if to make the point, the movement to protect children from violence actually benefited from the analogy. In Manhattan 1873 Mary Ellen McCormack was being badly beaten and neglected by her adoptive mother, so much so that her neighbors noticed and informed the Department of Public Charities and Correction (which managed the city’s orphanages, jails, public hospitals, insane asylums, workhouse and almshouse).3 The lack of laws that specifically protected children prompted the caseworker Etta Wheeler to contact the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.4 The founder of the society Henry Bergh saw the girl “as a vulnerable member of the animal kingdom needing the protection of the state”.5 The ASPCA recruited a lawyer who took the case to the New York State Supreme Court in 1874,6 and Mary Ellen was eventually removed from her adoptive mother’s home before being adopted by Etta Wheeler and some of her family members.7 The case motivated Bergh, her lawyer, and the philanthropist John D. Wright to found the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children- the first child protection organization in the world.8

The analogy between the children’s and animal movements is far from perfect; parents feel love for their children despite the abuse9, 10 and helping children now can benefit third parties down the line—more productive workforce, reduction in healthcare costs from developmental issues, etc.—with animals the benefit is entirely one directional (although it’s possible there may be some positive externalities associated with a generally violence-free society). Nevertheless, understanding the historical movement—including social forces, legal progress, and the tactics employed by advocates—towards the increasing consideration of children’s interests remains an important learning opportunity for animal activists.

Early violence against children

For our purposes it makes sense to focus on violence in the western world, because the western world pioneered children’s rights legislation, and the examples below were chosen so that they can be treated as part of the historical lineage of modern reform. We should note, however, that hunter-gatherers constitute an important exception among human societies, in that they rarely used corporal punishment, if at all.11, 12 This may be due to the egalitarian nature of these societies,13 or because “misbehaviour by a hunter-gatherer child will probably hurt only the child and not anyone or anything else, because hunter-gatherers tend to have few valuable possessions”.14 This is not necessarily indicative of greater recognition of the interests of children, however, as infanticide was prevalent in these societies.15

The child-rearing that dominated much of pre-Enlightenment Western human history can be traced back to the bible. In proverbs 13:24, one reads “He that spareth the rod hateth his son: But he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes”. The expression “Spare the rod and spoil the child” was probably coined by an advisor to the King of Assyria in the 7th Century BCE and may have been the source of the proverb.16 Colin Mather, a US puritan minister active around the turn of the 18th century believed that a child was “Better Whipt than Damn’d”.17 Original sin had endowed children with innate depravity which must be beaten out of children if they have any hope of being socialized and/or securing a spot in heaven.

These beliefs seem to be reflected in behavior. Although credible sources are sparse, it appears that severe corporal punishment was common for centuries. For instance, of the data available, a survey carried out in the USA found that 100% of respondents in the second half of the 1800’s were beaten with a weapon of some sort.18 This behavior was probably the social norm. Psychohistorian Lloyd deMause writes that “Public protest was rare. Even humanists and teachers who had a reputation for gentleness approved of the severe beating of children.” Memories of childhood torment did not deter parents from inflicting similarly harsh punishments onto their offspring, and “Century after century battered children grew up to batter their own children.”19

Some of the earliest significant positive changes in the conceptualization of children and childhood can be attributed to thinkers of the Enlightenment.20 John Locke’s doctrine of the blank slate and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s notion of ‘original innocence’ along with the ideas of some others from the era led to a radical shift in the conceptualization of children, predominantly among the elite.21

The 19th century in England saw the implementation of some of the world’s earliest children’s rights legislation. The English example is also particularly important because of the influence it has on the rest of the world, for instance in terms of attitudes to corporal punishment. The Research and Information Coordinator of the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment Sharon Owen tells us that:

“… corporal punishment as a method of “disciplining” children (and wives, servants, apprentices, etc) was spread globally largely in the context of colonialism, slavery, by missionaries etc – so whatever childrearing methods were originally used, the British way was to beat the child – one of our most shameful exports. The English common law defense of “reasonable chastisement” was taken to colonized countries, influencing behavior but also laws (as ways of living etc were codified), so laws (e.g. criminal codes) around the world which include this or similar provisions can be directly traced to British influence (the Caribbean is a good example, as well as many other commonwealth countries). Ironically, though, many countries which defend whipping, flogging, etc claim it is part of their culture – pointing out that it originated in the context of slavery, say, can be a powerful advocacy moment.”22

The period in which England began implementing laws to protect children will be discussed below.

The development of children’s rights in England

According to the socio-economist Viviana Zelizer, “Until the eighteenth century in England and in Europe, the death of an infant or a young child was a minor event, met with a mixture of indifference and resignation”.23 Historian Lawrence Stone writes that “…in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century very many fathers seem to have looked on their infant children with much the same degree of affection which men today bestow on domestic pets, like cats and dogs”.24 Further, English parents did not (or at least not commonly) buy symbols of mourning to commemorate these deaths through the sixteenth to early eighteenth century and rarely attended young children’s funerals.25

By the nineteenth century things were drastically different. According to Zelizer, “the death of a young child become the most painful and least tolerable of all deaths.”26 The widespread parental mourning was so great that ‘consolation literature’ (which as the name suggests, advised parents on how to cope with their grief) became a popular genre; and by the mid-1850’s children had been dubbed “small household saints” and now had elegant coffins designed if they passed away.27 This domestic grief experienced by parents was soon considered a public concern.28 Whatever the source of the heightened moral status of children, it was partly responsible for the development of precedent-setting children’s rights legislation. However other factors also played a role, including the affluence generated by the industrial revolution, which reduced the need for child labor and generated sufficient tax revenue to provide social services such as free schooling to increase the skill level of the workforce.29

The development of law relating to children was a complicated task. Alongside much resistance to these laws in general, the task was complicated for the lawmakers themselves. Laws are enforcement of rights, and these rights are meant to guarantee the interests of those they affect. However, these interests are only those “which the subject himself or herself might plausibly claim in themselves,” which leads to tricky considerations.30

Broadly speaking, children can be considered as having three interests; basic interests, such as the interest in receiving necessities such as physical and emotional care;31 autonomy interests, which are interests relating to “the freedom to choose his [or her] own lifestyle and to enter social relations according to his own inclinations uncontrolled by the authority of the adult world;”32 and developmental interests, the interest in having “their capacities…developed to their best advantage.”33 These interests are not always in alignment. The autonomy interest diverges from the developmental and basic interests in some cases—consider the desire of a child to procrastinate schoolwork now vs the later regret of his adult self—yet both of these interests are held by the same person at different times in his life. Should the basic and developmental interests trump autonomy interests? More importantly for our purposes, which interests won out in the course of history? Like for children, the autonomy interests of animals are not always in their best long term interests (for instance dogs eating chocolate, which leads to health issues). Understanding what interests won out with children could be instructive in finding the path of least resistance with which to advance animals rights. Children’s rights legal precedents could be used to justify arguments in the courthouse.

The progress of English law relating to children will be documented up to the Infant Life Protection Act of 1897, with the conflicts between different interests being noted throughout. Early English law viewed children as a means to transfer property down the generations. According to historians F. Pollock and F.W. Maitland, the law:

“never laid down any such rule that there ought to be a guardian for every infant. It had been thinking almost exclusively of infant heirs…The law had not even been careful to give the father a right to custody of his children; on the other hand, it had given him a right to the custody of his heir apparent, whose marriage he was free to sell.”34

In a sense, the role of children in society was therefore “furthering the interests of the family group”.35 They were not generally considered to have interests themselves. Other aspects of early law reiterate lack of consideration for the interests of children. The writ of wardship and the action for abduction directly affected children, but were grounded in the father’s proprietary interest.36 No laws required parents to support their children.37 Legislation relating to children aimed at ensuring the interests of the parents, predominantly the father, right up until the late 19th century.38 However, criminal law always protected children from severe injuries inflicted by their parents.39

The Factory Acts passed in the first half of the 19th century were construed to assure the interests of children were respected. The 1833 Act included regulations concerning the age of children allowed to work in factories, the minimum amount of schooling required and the appointment of factory inspectors to ensure the laws are respected.40 By modern standards, these laws would be considered drastically insufficient, but they were a significant improvement to previous legislation. The Factory Acts were amended throughout the century and became increasingly accommodating to the interests of children.41 As mentioned, the wealth created from the maturing Industrial Revolution probably made it easier and more appealing to implement these laws. Legislators were forced to decide which of the children’s interests had priority, and developmental interests gained ground faster than autonomous interests. For instance, compulsory and free schooling applied regardless of whether children wanted to attend.42

As mentioned, a relic from this historical era in England has been particularly hindering to the development of corporal punishment laws generally (which we will examine later). The “reasonable chastisement” defence in England, according to Sharon Owen has been “so influential the world over, and is still one of the greatest obstacles to countries achieving prohibition of corporal punishment”.43 This defence comes from a case ruled on by Chief Justice Cockburn in 1860 who said that “By the law of England, a parent…may for the purpose of correcting what is evil in the child, inflict moderate and reasonable corporal punishment, always, however, with this condition, that it is reasonable and moderate”.44

1872 saw the creation of the Infant Life Protection Act. The law was the result of protests against ‘baby-farms’ and required that paid caretakers of at least two infants less than one year of age register to and report deaths to local authorities.45, 46 Sponsor of the Act W.T. Charley argued that it would protect infant life. The law was poorly enforced and was not particularly rigorous—private homes did not have to be inspected, and day nurseries were not taken into account—but it nevertheless represents a clear (albeit half-hearted) acknowledgement that children have interests.47, 48 The law was in line with all three of the children’s fundamental interests. A revision of the Act in 1897 broadened the concern from infants to young children, requiring that all children under the age of 5 be registered.49

Around the same time, there was an increasing willingness to renege the parental interest when the possession of a child by his father was considered to put the child in bodily danger, although this only applied in what would now be considered extreme abuse cases.50 In a similar vein, The first Prevention of Cruelty to, and Protection of, Children Act of 1889 made it a crime for over-sixteens who had custody of children to willfully cause them unnecessary harm or suffering, be it from neglect, ill-treatment, abandonment or exposure.51 While it is a clear sign of consideration of children’s interests, other motives may also have been at play, including the Christian evangelical movement’s concern for the nation’s ‘moral health’.52

Widely held social views also played an important part in influencing the development of children’s rights, as the parents’ interests were subordinated to those of the society at large. For instance, parental behaviors perceived as radical, reckless, profane or immoral were often the justification for denying parental custody, because of the ‘repulsive’ nature of their actions. On the other hand, this implies that children’s rights were confounded with and depended on social norms; and one of the prevailing norms of the time was that the interests of parent—as especially father—should be enforced.53

This was undoubtedly a significant hindrance to the development of children’s rights.

In essence, by the turn of the 20th century, children’s interests were legally recognised and were clearly distinct from those of parents (or other third parties). However the scales of justice were still inclined to clearly favour parental interests. When conflict arose, children’s autonomous interests were subordinated to their developmental and basic interests, although there were no major conflicts between the interests in this period because the consideration of children’s interests was such a new phenomenon. The legal intricacies deserve more research elsewhere.

We will now examine in more detail the most important precedent setting children’s rights legislation of the modern era—the abolishment of corporal punishment in all its forms, which occurred in Sweden when they prohibited corporal punishment in the home, having already prohibited it in all other settings.

Sweden—The ban of corporal punishment

“The prohibition of spanking represents a stunning change from millennia in which parents were considered to own their children, and the way they treated them was considered no one else’s business…it is part of the historical current toward a recognition of the autonomy of individuals.”

-Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of our Nature.

Changes in legislation

Sweden can be considered as the pioneering nation in terms of treatment of children in the last half-century. Joan Durrant, a leading Researcher into corporal punishment and the Swedish case particularly, explains that:

For 5 years, from 1979-1983, Sweden was unique in the industrialized world for having passed the first explicit ban on corporal punishment. To many of us, particularly those of us living in North America, this appears to have been a radical and, to some, intrusive legal development. However, from the Swedish perspective, the law was the logical conclusion of an evolutionary process that unfolded over a period of decades.54

This “evolutionary process” was inaugurated in 1918 when corporal punishment was banned for “senior grades of elementary school”,55 before being extended in 1928 to include all corporal punishment in secondary school gymnasiums thanks to public concern surrounding severe beatings experienced by children.56 In 1949 the Parenthood and Guardianship Code was amended so that the word ‘punish’ was replaced by ‘reprimand’.57 Despite these changes, parental violence did not decrease sufficiently to satisfy the public and legislators. Most held that this was because the Parents’ and Penal Codes contained explicit legal defenses for corporal punishment, and following a removal of the relevant Penal code section in 1957, the Parents’ Code followed suit in 1966, eliminating the legal ambiguity that had existed in the intervening 9 years.58, 59 The need for corporal punishment in schools was also being questioned in this period. Some schools underwent an experiment in 1959 where they refrained from the use of corporal punishment to evaluate its efficacy. Despite initial resistance to the idea and debate in the media, the experiment changed the opinion of many educators and in turn members of the public and as a result corporal punishment was abolished in child care institutions and reformatory schools in 1960.60 In 1962 this measure was extended to include the entirety of the school system.61 Despite the fact that corporal punishment was no longer explicitly permitted, ambiguity persisted. It was unclear whether corporal punishment was forbidden, or rather not approved of but allowed. The definitive turning point came in 1977. A father who had badly beaten his 3-year-old girl two years previously was acquitted by the court. This prompted a 60,000 person demonstration in Stockholm and the signing of a petition demanding more stringent corporal punishment laws. The government responded by forming a Commission on Children’s Rights to review existing legislation. The Commission proposed an explicit ban on corporal punishment, and following a “remiss procedure” and in 1979 the law was proposed, voted upon, and overwhelmingly passed by the Swedish government.62 It reads:

“Children are entitled to care, security, and a good upbringing. Children are to be treated with respect for their person and individuality and may not be subjected to physical punishment or other injurious or humiliating treatment.”63

No penalties are associated with the law (unless the violence is considered assault, in which case laws against assault apply, just as they apply to adults), which was intended to change the public perception of corporal punishment in the home and as a guide for parents.64, 65

Underlying social currents

Joan Durrant has argued that 1) a recognition of children’s rights and 2) a collectivist approach to social policy, were vital in the success of the 1979 legislation.66 The corporal punishment ban was one of many social/political changes stemming from these two elements of the broader social context.67 The relevant aspects of Sweden’s cultural context in the 20th century will be considered below.

In 1909 recognition of children’s rights spread somewhat with the publication of the Swedish author Ellen Key’s The Century of the Child, in which, while writing about education, she:

‘…emphasized the freedom and individuality of the child; she argued for equality in the home; she was opposed to corporal punishment; she fought for co-education and common schools for all children, regardless of the social class; she saw the activity of the child as central…’68

However, her views on these subjects went unnoticed initially, before later being implemented in Swedish policy.69 The book’s publication occurred soon after the founding of the Social Democratic Party (1889) during a period of rapid industrialization and economic growth along with a low fertility rate. There was a greater willingness and ability to be concerned for children; these factors together helped make children’s rights a mainstream issue.70

In 1934 Nobel Laureates Alva and Gunnar Myrdal published the highly influential Crisis in the Population Question. While they were concerned with the effects of population decline, their recommendations which aimed to increase the fertility rate included a housing subsidy program for families, free prenatal care, and maternity benefits for most new mothers, which were implemented before the Second World War.71 These social changes made it easier to meet children’s needs, and there was a growing willingness and ability to meet these needs. This was manifested in actions undertaken relating to (using Durrant’s categorization) 1) The right to an environment free of violence, 2) The right to a safe environment, and 3) The right to government accountability.

- Swedes imposed significant limits on the violence which could enter into a child’s life. ‘Commercial violence’, for instance was highly regulated. One example of this is the self-imposed ban by toy retailers in 1979 regarding the sale and marketing of violent toys. Likewise, and around the same time, the Play Environment Council and Consumer Ombudsman agreed to ban the sale of products with ‘military/martial associations’.72 Many other similar agreements were later signed. The corporal punishment ban should be interpreted as one of many measures aimed at ensuring this particular right of the child.73

- Swedes viewed the right of children to physical integrity as more than just protection from physical assault. As such, there was a concerted effort by government agencies to minimize accidents in public and private places. Another motivation to minimize accidents in private places such as the home was that it reduced the need parents feel to inflict corporal punishment upon their children.74

- The appointment of an official Swedish Ombudsman for Children (1993) reflected the recognition that government has to play a role in safeguarding the interests of children.75

Also, Swedes had a collectivist approach to social policy. Since the 1930s they had considered that the family and state should work in partnership to ensure the well-being of all family members.76 Ensuring that the interests of children were accounted for was considered a collective responsibility. Many policies implemented before and after the ban reflected this, including free health and dental care for children (1955),77 substantial paid parental leave (which was first introduced in the 1940s and broadened to cover fathers in the 1970s),78, 79 legal entitlement to day care for children between one and six years old (1995),80 and free parental education programs.81 Furthermore, the generous parental leave was indicative of Sweden’s general parent friendliness. This was also significant as it showed that “corporal punishment was not about pitting children’s rights against parents’ rights”.82 The corporal punishment ban was one element which emerged from this broader socio-political environment which increasingly took into consideration the interests of children.

The emergence of a strong children’s rights movement was also important in encouraging changes in public opinion, and the organizations Swedish Save the Children and Children’s Rights

in Society were particularly influential.83 The tactics of activist organizations will be discussed later on, focussing on such activity in New Zealand.

How did this broader environment arise? Perhaps a better question is to ask how the broader environment arose in Nordic countries more generally, because the four of the first six countries to outlaw corporal punishment were – not coincidentally – from the region. Finland in 1983 (2nd), Norway in 1987 (3rd) and Denmark in 1997 (6th). For a region of only five countries, this is astounding (Iceland followed later in 2003 as the 11th country to abolish corporal punishment).84 The Economist writes that:

Nordic government arose from a combination of difficult geography and benign history. All the Nordic countries have small populations, which means that members of the ruling elites have to get on with each other. Their monarchs lived in relatively modest places and their barons had to strike bargains with independent-minded peasants and seafarers.85

These serendipitous circumstances led the region to embrace liberalism early by global standards; by 1766 Sweden had guaranteed freedom of the press, by 1840 had stopped privileging aristocrats and created a meritocratic civil service. The power of the church was reduced thanks to the widespread adoption of Protestantism.86 The result of such a heritage is high levels of trust in others and a belief in individual rights. The World Values Survey from 1981-1984 asked residents of 10 countries if “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?”. Two Nordic countries, Finland and Sweden, were among the countries surveyed and they displayed the highest levels of trust. 56% of Fins and 52.5% of Swedes answered that “Most people can be trusted” while Australia came in third, with only 46.3% respondents giving the same answer.87 The Nordics are also the “world’s biggest believers in individual autonomy”.88

High levels of trust in others explain the collectivist approach to social policy in Sweden; likewise, the concern for individual autonomy—the interests of individuals, in this case children—was present in the broader environment in which the 1979 corporal punishment ban emerged. “They regard the state’s main job as promoting individual autonomy and social mobility”.89

Another question arises: if Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Norway and Iceland share a broadly similar model of big government and individualism, why was Sweden the first country to ban corporal punishment 4 years before Finland followed suit? This is a difficult question, and it is quite possible that Sweden simply held certain necessary beliefs more strongly than its Nordic neighbors. It is also quite possible that luck played an important role—more precisely, that Sweden happened to host a particularly bad case of child abuse that propelled the corporal punishment issue into the limelight. Recall that the acquittal of the abusive father in 1977 prompted a public uproar, which led to the creation of the Commission on Children’s Rights. Economist Cass Sunstein and jurist Timur Kuran have proposed a mechanism to explain this kind of happening: an availability cascade, which is

a self-reinforcing process of collective belief formation by which an expressed perception triggers a chain reaction that gives the perception increasing plausibility through its rising availability in public discourse.90

Here they make reference to what psychologists call an availability heuristic, which refers to the fact that probability assessments we make are often based on how easy it is to think of relevant occurrences of an event.91 The availability cascade is a broader notion of this heuristic, which also takes into account the effect of emotional charge on probability assessments.92

The availability cascade explains how media coverage of even a relatively insignificant event can culminate in large scale government action. A media story about a risk (here, the risk of child abuse) arouses the worry and concern of a niche group. The emotional reaction of this group is covered by the media, which also constitutes additional media coverage of the initial event. Thanks to the availability heuristic, child abuse is then judged to be more common, which prompts additional concern and involvement in the cause. Attention-seeking media headlines exaggerate the danger, which intensifies the emotional charge of thoughts relating to child abuse, which is thus deemed even more common. Availability entrepreneurs–individuals or organizations who try keep the issue in the limelight (in this case Swedish Save the Children and Children’s Rights in Society)—speed up this process. The democratic process ensures that the issue becomes political as it is on everyone’s mind, and brings children’s rights to the forefront of governmental priorities.93 However, specific information and empirical evidence regarding the Swedish event was hard to find, so this explanation should be treated as speculative.

The factors discussed here are obviously not exhaustive. Staffan Janson points out that:

Economic development and the institution of paid parental leave decreased parents’ stress level. Technological inventions produced safer homes, lessening the need for harsh discipline. Also, since more children attended preschool, it became increasingly difficult for abusive parents to hide their children’s bruises. But most importantly, the continuous growth of a democratic, egalitarian ideal meant that more and more Swedes felt that all people—children too—should enjoy equal protection from violence.94

Differences in relatively minor causal factors like parental leave policies and preschool attendance rates may also help account for the timing differences between the Nordics in banning corporal punishment, while the most important shared “democratic, egalitarian” and autonomy-respecting ideal explains their historical proximity.

Another thing to take into consideration is the specificities of the law itself. As Sharon Owen tells us:

“… One key element that would need to be considered is the length of time the process of law reform takes. For example, Brazil achieved full prohibition in 2014, but drafts of prohibiting legislation had been under discussion for over a decade; in Peru, Congress gave all-party support to complete prohibition in 2007, but prohibiting legislation is yet to reach the statute books (it is hopefully imminent). In some countries, law reform has apparently progressed fairly quickly; in others, particular obstacles are faced unrelated to the issue of corporal punishment. In Slovenia, prohibition was included in a Family Code Bill which was ultimately rejected due to opposition by a conservative group to the provisions on same-sex partnerships. In the Philippines, many bills have been drafted and tabled, sometimes in tandem, but none has yet completed its journey through parliament. Sometimes parliamentary processes have been disrupted by natural disaster. Things like national elections, whether a bill has to go through a referendum, whether the parliament has a one or two house system etc all play a part—as do the strength and organization of the opposition, political coups and terrorist activities, environmental events, wars etc. (In terms of campaigning/activism, this “big unknown” is why the Global Initiative in all our planning is concerned to emphasize that we must be flexible and opportunistic in our approach, as well as strategic in the longer term.) And there always have to be hard decisions about whether to draft a bill which only addresses prohibition of corporal punishment or whether to include this as part of a more wide ranging bill. There are pros and cons to both: the former is not complicated by other issues but inevitably engages everyone in debate on the issue, the latter can sometimes mean that prohibition almost slips in when the focus is elsewhere but equally it can mean it is held up by other issues—there are successful examples of prohibition being achieved both ways.95

The impact of the Swedish law

We have up to this point investigated important law changes in the children’s rights movement. Law change is undoubtedly essential to the animal movement. However in the interest of optimizing the time and resources of activists, it is important to understand just how effective law changes are in bringing about change in actual behavior. The impact of the Swedish law is evaluated below.

The effect of the law on public opinion

The Children’s Rights Commission which recommended the ban to the Swedish government suggested that it could change long-term public perceptions of violence against children.96

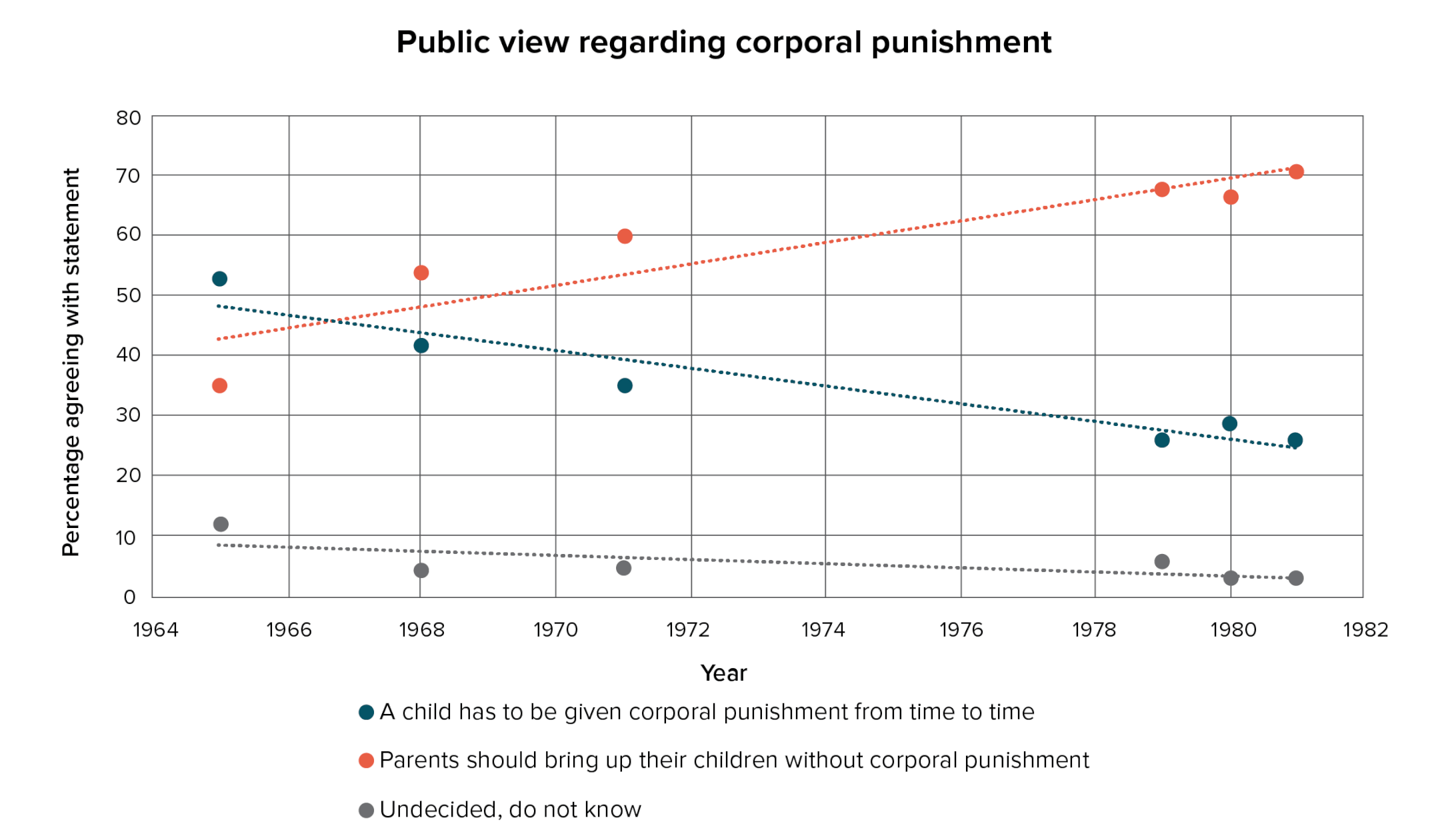

Indeed, public approval of corporal punishment in Sweden has long been in decline. The opinion research institute (SIFO) carried out polls intermittently between 1965 and 1981 to ascertain the level of public support for corporal punishment.97 They asked respondents whether they agreed with the statements that 1) A child has to be given corporal punishment from time to time, and 2) Parents should bring up their children without corporal punishment, with the option of responding with 3) Undecided, do not know.98 The results are displayed below, fitted with linear trend lines:

Note that the two statements are not antonymous. The statement ‘A child has…’ implies a belief in the necessity of corporal punishment, whereas ‘Parents should…’ indicates a belief that the use of disciplinary alternatives is something to be proud of. In principle one could believe that corporal punishment isn’t necessary but that it’s no worse (or better) than the alternatives. However, respondents treated the two questions as if they were opposites as the trends in each case are negatively correlated. Indeed, as legislation prohibiting violence against children was passed in Sweden, the public has become less supportive of corporal punishment. Interestingly, the percentage of people who responded ‘Do not know’ dropped sharply from 12% in 1965 to 4% in 1968 (in 1966 the section of the Parental Code allowing corporal punishment was removed), and again from 6% in 1979 to 3% in 1980 (corporal punishment in all its forms was explicitly banned in 1979). This suggests that the law changes got people who had not previously thought much about the issue to do so, and that they generally came away with a negative view of corporal punishment. This is speculative, and seems somewhat tenuous as an explanation of the drop between 1965 and 1968 considering that a poll conducted in 1971 found that only 40% of the population were aware that corporal punishment was no longer permitted.99 It’s a more plausible explanation of the decline in “Don’t know” responses, of the 1979 to 1981 decline, though this time period doesn’t fit the pattern of decreasing support for corporal punishment (support through this period is roughly constant); in 1981, 99% of Swedes were aware of the 1979 ban, a level of awareness unrivaled “in any other study on knowledge about law in any other industrialized society”.100

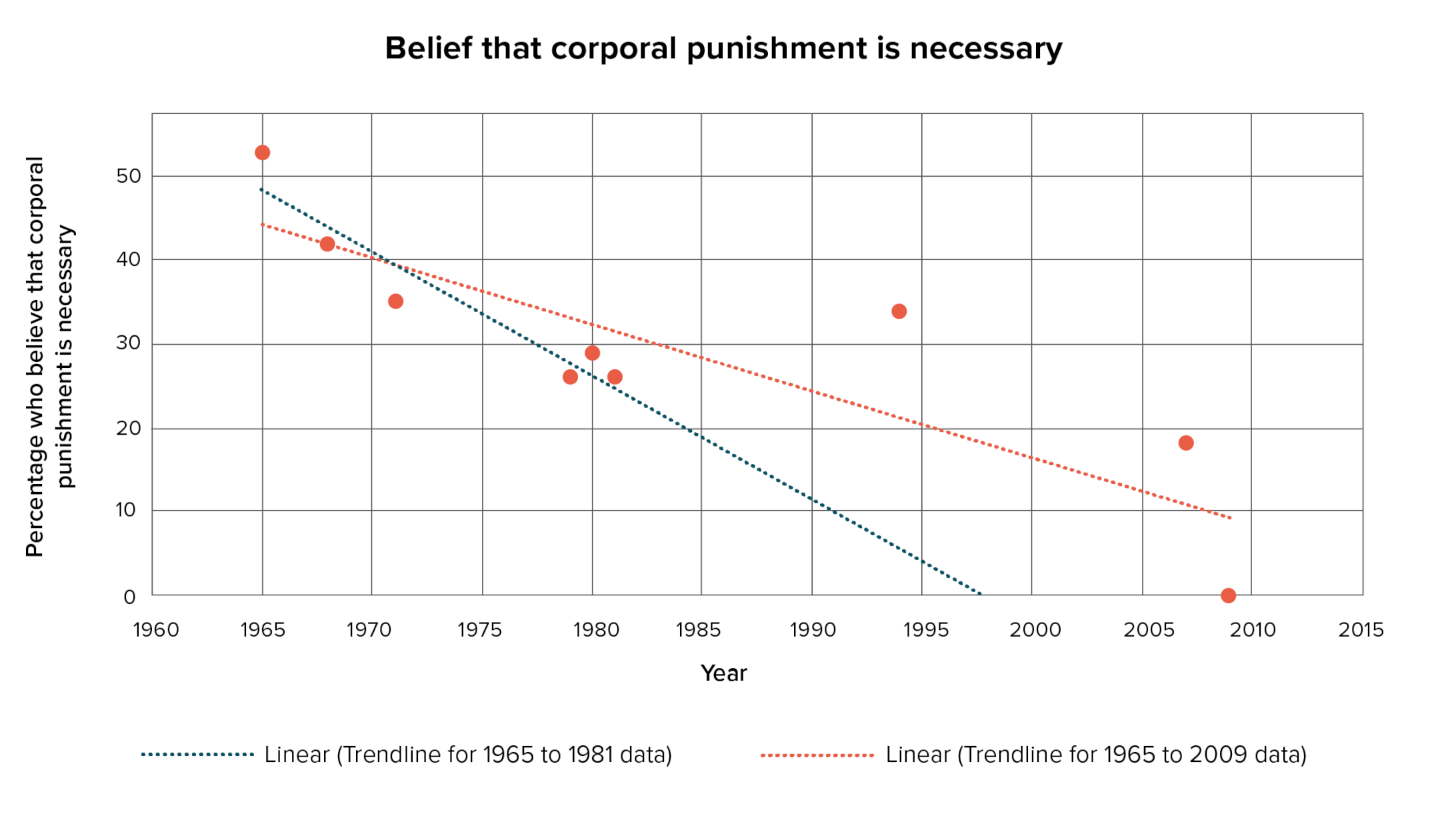

The trends of agreement with statement from the SIFO study ‘A child has to be given corporal punishment from time to time’ can be extended to 1994 if one accepts the statement from a government survey as synonymous: ‘moderate corporal punishment is necessary in some childrearing situations, but if used, it should be thoroughly considered and not an effect of anger’.101 They can be extended to 2009 thanks to a study published in the International Journal of Pediatrics which included a survey asking respondents “Do you believe that in order to bring up (raise, educate) (target child’s name) properly, you need to physically punish him her?”102 A 2007 study also presents the percentage of the population who believe that ‘Rearing a child without mild corporal punishment inconceivable’, without explicitly stating the question asked.103

Jumping from survey to survey, we find that in 1994 approval for corporal punishment had slightly increased to 34%, before decreasing to 18% in 2007 and dropping sharply to 0% in 2009.104 The trendlines indicate that the decline in support for corporal punishment slowed from 1981 onwards. However this could be due to inaccurate survey data. For instance, the 1994 data point is a conservative estimate; another study found that the percentage supporting corporal punishment in 1994 was 11%, highlighting the highly uncertain nature of these surveys.105

Other surveys also indicate a growing disapproval of corporal punishment. A 2011 study found that in 1994 “92% of parents thought it was wrong to beat or slap a child”106 , a 2009-2010 survey of 12-16 year olds found that 84% disagreed with the statement that “parents have a right to use mild forms of corporal punishment on their children (e.g. smacking)”, and 93.6% agreed “children must be protected from all forms of violence”.107

What should we make of these data? Durrant wrote that “the corporal punishment ban and ongoing public education campaigns appear to have been extremely effective in altering the social climate with regard to corporal punishment.”108 Is she right to claim that the decline in support for corporal punishment a consequence of the criminalization of the practice?

If so, what might the social mechanisms behind this link be? Criminologist Detlev Frehsee evokes the role that laws play in shaping social norms. The sanction the law imposes defines the norm, which “becomes omnipresent as a binding value and can be accessed at any time. Its decisive contribution is to provide an orientation for all related interactions”.109 For such a value to become omnipresent and binding, it must be widely known.110 This norm translates into change by procuring a means of communication for the persons involved, in this case the child or those concerned for the child. Their position is legitimized by the authority of the legislation.111 The conflict has also changed nature; it is no longer a private matter concerning the family, but is “transferred into the legal system that provides an external reference structure”.112 In turn, parents realize their acts are no longer considered legitimate and children know that being spanked is not something they have to put up with. Parents who had second thoughts about their behavior can no longer rationalize it by reminding themselves that there is no legal ban. As a result, positive opinions of corporal punishment are expected to drop.

Perhaps increased parental awareness of the view of the scientific community that corporal punishment is ineffective and harmful is the explanation. Not only was the ban almost unanimously known, but parents were sent a 16 page pamphlet which explained the reasons for introducing the law as well as alternatives available to corporal punishment and information regarding the law was printed on milk cartons for two months.113 This could explain the downward trend in belief in the necessity of corporal punishment and the growing view that childrearing without corporal punishment is positive.

Sociologist Kai-D Bussman thinks that the fact that the law arose in an environment of changing values is important. He writes that “A slap is a symbolic action demeaning another person, and precisely such intentions have less legitimacy in the observed changes in the system of values”.114 Furthermore, as the laws banning corporal punishment in schools show, violence is increasingly being deemed inappropriate in an educational environment and therefore “This development is heading…in the direction of nonviolent and discourse-oriented conflict-solving patterns.”115 In a later study (and not exclusively discussing Sweden), Bussman emphasizes the role that the spread of information has in changing opinion: “Continuous campaigns and information measures to promote nonviolent childrearing…could give this trend even more impetus. The numerous communication options in the mass media could be used to spread information on the existing laws”.116 This implies that widespread knowledge of a law can be considered widespread knowledge of a social ‘value’ norm, and that the perceived existence of such a norm by non-conformers will likely change their attitudes.117 This is because law is “a communicative resource with a highly symbolic meaning”.118 Bussmann cites a survey conducted in Germany concerning the population’s conception of violence; a slap from parents was not often regarded as violence, whereas a slap from teachers usually was. He posits that this is because the law in Germany has legitimated one and not the other.119

The view that the law drove down public esteem for corporal punishment is not unanimous. Jurist Julian Roberts notes that the decline is a long term trend, which began far before 1979 (although the available data only goes back to 1965), and that the decline of previous years was did not speed up following 1979.120 On the contrary, approval for corporal punishment actually went up in the year following the ban. Likewise, if the law is the causal factor in initiating opinion change, one wouldn’t expect to see similar decreases in other countries without equivalent legislation. But we do; in the United States for example, 94% of respondents agreed with the statement that “It is sometimes necessary to discipline a child with a good hard spanking” in 1968. This number had dropped to 68% by 1994.121 This equates to a decline of 26% of the total population or 27.7% of original supporters that stopped supporting corporal punishment; the equivalent declines in Sweden from 1965 to 1994 is of 19% and 35.8%. The decrease in Sweden of a smaller percentage of the population, but a higher proportion of those who thought corporal punishment was acceptable changed their minds. Similar downward trends have been observed in many countries including New Zealand122 and even Kuwait.123 If we assume the marginal difficulty of changing opinion to be constant, than the law probably had no impact or perhaps even a negative one. However, if we assume some degree of increasing marginal difficulty of changing opinion (target individuals become progressively less receptive to the anti-corporal punishment message), then the opinion change of people who originally supported corporal punishment is more pertinent. For instance, if we assume that each marginal individual’s opinion is twice as hard to change as the previous individual, then change from 0% to 50% of people should be counted as equal to change from 50% to 75%. So, if the marginal difficulty of changing opinion increases, the proportional change is more relevant than the total change, and Sweden’s 35.8% trumps the equivalent 27.7% from the United States. Roberts seems to assume that the marginal difficulty of opinion change is constant. It is unclear which view is correct in the case of corporal punishment views, and it is possible that there is a decreasing marginal difficulty of opinion change; in other words, that it actually gets progressively easier to change opinion as more people become convinced (perhaps due to the pressure to conform to societal norms). Roberts also examines “the issue of attitudes to corporal punishment within the broader context of public attitudes towards other social issues”, and states that “The general finding appears to be that while shifts in public opinion occur, the are almost never in response to legislative reforms”.124

Conclusion

The data available are an insufficient basis upon which to determine definitively the impact of the law/s on opinion change. It seems likely that public approval for corporal punishment would have continued to decline independently of the laws in the broader context of gradually spreading liberal, autonomy-respecting values. However, the law might spur on opinion change by legitimizing the view it represents–it’s a symbol of recognition of a new social norm– so in this respect perhaps opinion change leads to law change, which in turn leads to more opinion change.

The effect of the law on behavior

What was the effect of the law on prevalence of corporal punishment? Some data comes from surveys asking parents retrospectively about their behavior, and there is good reason to doubt self reported punishment claims. Before corporal punishment was made illegal, parents may have had no qualms telling surveyors that they regularly hit their children. After it was made illegal, however, they probably weren’t quite as keen to own up to a crime. Nevertheless, decreasing reported rates of corporal punishment, while probably not being an accurate reflection of these rates, can be considered a victory of sorts because it indicates an increasing distaste for such childrearing methods. Such data would therefore reinforce the trends of the previous section.

Various surveys can be put together to get an idea of the general trend of corporal punishment rates. A longitudinal study of a cohort of families which began in 1954 recorded mothers’ reported use of corporal punishment, and in the 1950s 54% of mothers had beaten their children, with a third doing it at least once per day.125 In 1980, survey data was collected which asked a representative sample of Swedish parents to report their use of corporal punishment. 28% of respondents had used some form of violence against their children in the past year.126 It was the first study to use a large and nationally representative sample.127 The next of these nationally representative surveys was carried out using the same methodology in the year 2000.128 In 2000 this number fell to 1.1%, before rising to around 3% in 2006 and remaining there till 2011. Staffan Janson who ran the studies speculates that the slight increase from 2000 may be because “the study in 2000 was performed using interviews and that the studies in 2006129 and 2011 were performed using non-identifiable postal questionnaires”.130

These data are impressive. In the 1950’s before the corporal punishment ban, 54% of mothers were willing to own up to having beaten their children; only 3% were in 2011. Even if the data from the smaller 1950’s study are moderately inaccurate due to the small sample, this is a huge decrease. It also indicates that most of the decline is in actual behavior (as opposed to the taboo now associated with admitting to corporal punishment) because when the 2006 and 2011 studies allowed people to remain anonymous, reported rates of corporal punishment only went up very slightly.

The behavior change was probably partly a consequence of the law. Durrant, Rose-Krasner and Broberg conducted a study in which they collected data pertaining to attitudes towards and use of corporal punishment (use rates reported by Swedish mothers). They note that there is a positive relationship between positive attitudes to corporal punishment and frequency of corporal punishment use (correlation coefficient 0.4), and an inverse relationship between negative attitudes towards corporal punishment and frequency of use (correlation coefficient -0.42).131 If, as Janson’s study seemed to imply, the reported rates of corporal punishment use are fairly accurate, then the attitude change resulting from the creation of the law (if we grant the law’s social-norm legitimization that much) can account for some of the behavior change.

The sanctions associated with infringing the law are also important. Two types of measures are possible: SoL (Socialtjänstlagen: Social Securities Act) measures and LVU (Lag med särskilda bestämmelser om vård av unga- roughly translates to: The teams with the care of the young) measures. SoL measures are voluntary and consist of either assigning a contact person to help, or placing the child in out of home care. LVU measures are the same but compulsory.132 Either of these measures can be implemented. Following the implementation of the law there has been an increase in the use of voluntary measures and a decrease in compulsory ones,133 indicating that the SoL measures seem to have encouraged parents to seek help earlier, in order to avoid the possibility of more severe interventions later on (e.g. the fear of losing custody of the child for a long period of time). The use of voluntary measures mean that parents have acted before the authorities had to, so earlier identification of problematic households occurs, and earlier identification allows the problems to be dealt with sooner.

Furthermore, the children that would have remained in abusive homes are now compulsorily removed if necessary; before, they would have remained victims of corporal punishment.

The law probably didn’t affect severe forms of violence. The study that surveyed Swede parents in 1980 also differentiated between different forms of violence and recorded equivalent responses from US parents. Rates of severe violence (biting, kicking, punching with fist, beating etc) did not differ between the two countries, despite corporal punishment in general being over two times more common in the US. This could be because these types of behavior are probably due to individual cases of psychological illness, as the rates of these behaviors were very low in both countries, which suggests that they are statistical outliers. Such behaviors probably won’t be impacted by the mechanisms discussed above.134

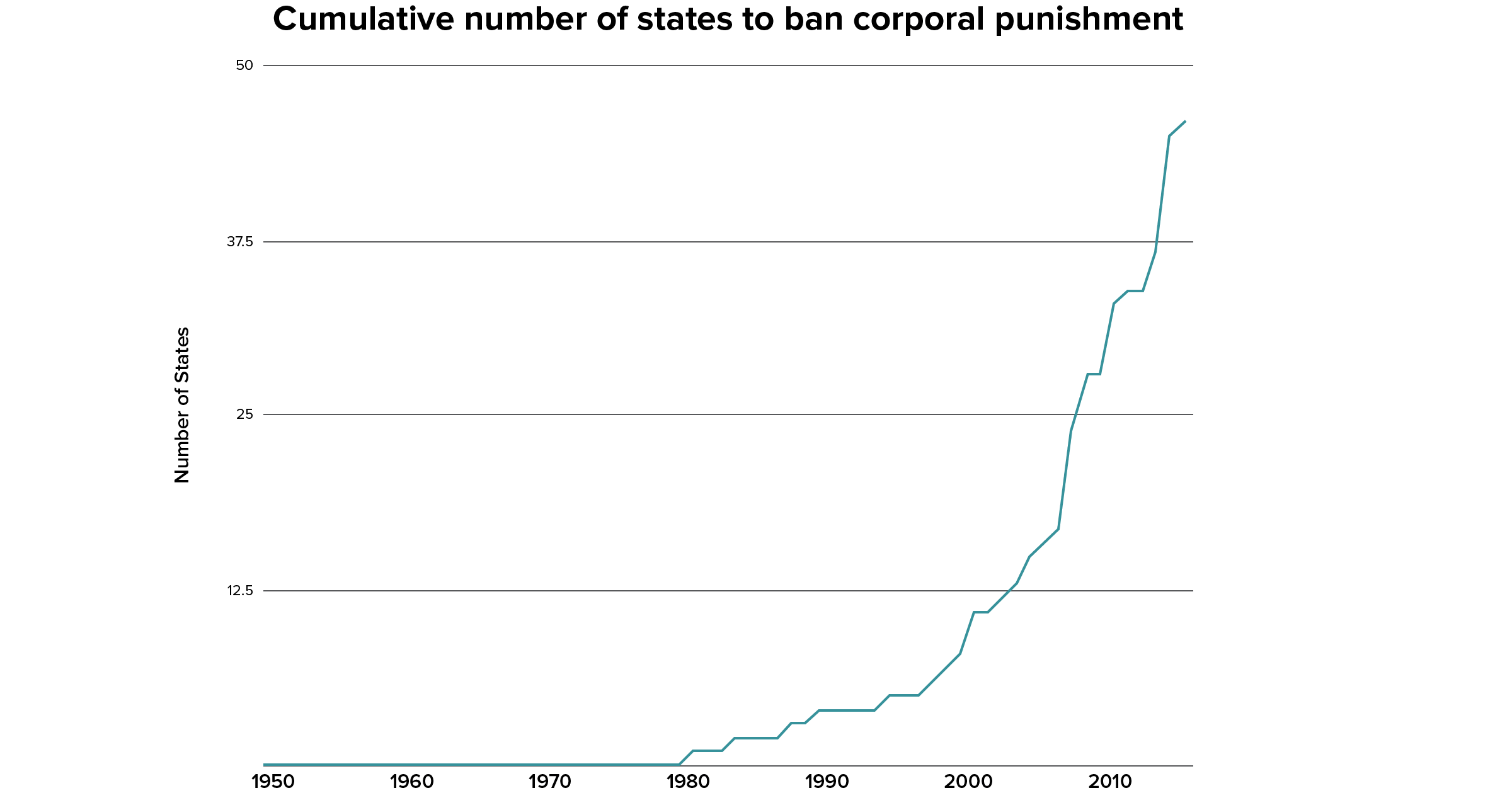

The impact of precedent-setting

The space of time within which corporal punishment prohibition occurred in many countries around the globe is extremely short, as is often the case with rights revolutions. After no such ban in the entirety of human history, the number of states with a full prohibition on corporal punishment grew steadily from 1 in 1979 to 8 in 1999, before beginning a sharp incline from then onwards, climbing to 46 states as of August 2015.135 Discerning the effect of Sweden’s precedent is difficult because we don’t know the counterfactual, but nevertheless there are multiple reasons for thinking that the Swedish precedent was influential.

For one, Sweden’s prohibition confirmed the possibility of an exception-free ban on corporal punishment, encouraging foreign governments and activists. It showed that the fears of opponents of the ban did not materialize; there has not been widespread jailing of parents, families have not been torn apart, crime rates have not increased, and so on.136 This likely spurred the neighboring Nordic countries to follow suit.

The influence was probably also in part due to cooperation between Swedish and foreign organizations. For example, Save the Children Sweden has long collaborated with the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, improving the Global Initiative’s effectiveness. Likewise, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency has long been one of the funders of the Global Initiative.137

The Swedish Government has also been an important change agent, for instance by actively taking part in the Universal Periodic Reviews of many states, questioning and encouraging governments regarding their progress towards banning corporal punishment.138 Sweden is also openly proud about its prohibition achievement. In its most recent report to the Universal Periodic Review, Sweden stated that it had worked proactively to abolish corporal punishment and that it now “planned to create a national knowledge centre of violence against children to coordinate and compile knowledge and to support actors in their work against corporal punishment”.139 It seems that in creating internal change, Sweden became one of the anti-corporal punishment movement’s leading proponents.

Sweden’s influence also probably grew over time. As Sharon Owen tells us:

Sweden’s influence has become stronger over the years due to the research that the passage of time has meant can be carried out. This means that when those who resist law reform – or who want it but worry about the consequences – think that it means children won’t be disciplined and higher crime rates will result, or that parents will go to jail and families will be broken up, or that it would be too costly, we can point to Sweden to show that when implemented well it needn’t mean any of these things.140

The effect is amplified as more countries ban corporal punishment successfully, so the effect is a snowballing one. This can explain the exponential growth in states banning corporal punishment.

While the Swedish example seems to have been useful in many countries, it may not be useful to all corporal punishment prohibition movements. Clearly, the usefulness of the Swedish example will vary on a case-by-case basis, depending on things like how Sweden is viewed in the country in which prohibition is considered. In some cases the impact could actually be negative; an example of this is countries which openly resist “European influence”, and so in this case proponents should try avoid Swedish associations.141

An investigation of activist activity in children’s rights—New Zealand

Corporal punishment in all settings is illegal in New Zealand. This was achieved when the Crimes Amendment Act of 2007 banned the use of violence in correcting children’s behavior.142 Activist activity in New Zealand has been particularly well documented and occurred in a post-internet age, making it useful to activists today.

The internationally renowned New Zealand author Katherine Mansfield wrote an implicit criticism of corporal punishment in her 1921 story Sixpence. In the story she movingly captures the distress and regret of a father who administered physical punishment:

…at the sight of that little face Edward turned, and, not knowing what he was doing, he bolted from the room, down the stairs, and out onto the garden. Good God! What had he done?…He felt awkward, and his heart was wrung.143

The story did not have any immediate observable consequences and New Zealand had to wait over half a century for formal anti-corporal punishment advocacy to begin. Psychologists Jane and James Ritchie were among the earliest advocates for a corporal punishment ban.144 They presented a submission to a Parliamentary Select Committee hearing in 1978, and argued (based on their research) that the committee should recommend banning corporal punishment. The committee did not follow their recommendations.145 In total, the Ritchies campaigned for over 30 years, lobbying politicians, publishing articles and books and speaking at conferences in an attempt to get corporal punishment banned. They were not successful, but influenced the thinking of future advocates.146 Another early advocate was Robert Ludbrook, a children’s lawyer who founded YouthLaw Tino Rangatiratanga Taitamariki, campaigning for many children’s rights including the right to a childhood free from violence.147

Organized child advocacy began in New Zealand in the 1980’s. The 1979 International Year of the Child partly inspired the creation of this movement, which was sustained by the New Zealand Committee for Children (established in 1980). The Committee was a proponent of the corporal punishment ban and encouraged the creation of the role of Commissioner for Children.148

The growth of this movement enabled certain advocates to become particularly influential.149 The continuity of influential advocacy from the 1990’s until the passing of the Bill in 2007 was essential.

Commissions (independent government-funded bodies)

The Office of the Commissioner for Children was influential.The Commissioner for Children (established in 1989) has multiple functions including advancing children’s welfare. Since the first Commissioner started condemning corporal punishment in 1992, the three subsequent commissioners reiterated this view, promoting non-violent childrearing as an effective alternative. They advocated through many forms of media (radio, television, newspaper and magazine articles) and lobbied politicians, assisted by the legal mandate associated with New Zealand’s ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.150 Despite regular criticism from the public, press and members of parliament along with subtle pressure from the government not to criticize their policies too vigorously, the commissioners were resolute in their message. Their “independent statutory voice” constituted important pressure against the legality of corporal punishment.151

Leading non-governmental organizations:

End Physical Punishment of Children (EPOCH) New Zealand was an organization founded in 1997 and was inspired by EPOCH worldwide (which was later renamed the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment), and aimed to abolish corporal punishment while advocating “positive non-violent child discipline.”152

Activities central to EPOCH were lobbying politicians (in person, by letter and by email), writing journal and newspaper articles, presenting at conferences and meetings (at both the national and local level), publishing a newsletter and setting up a website with information about the campaign against corporal punishment.153 Perhaps EPOCH’s most effective activity was persuading other NGO’s to support corporal punishment repeal. Save the Children published a book entitled Unreasonable Force: New Zealand’s Journey towards banning the physical punishment of children which is about NZ’s corporal punishment ban, and writes that EPOCH attained this widespread support by:

establishing an informal network of supportive organizations, recruited through personal contact, letters, telephone calls and, later, email. These organizations had no formal link with EPOCH, nor were they required to pay a membership fee or subscription. Network members were kept informed of developments through regular newsletters, bulletins and newsflashes.154

140 diverse organizations were part of this “informal network”, a significant number considering the population size of New Zealand. When the ban was being actively discussed in parliament, it became very difficult for opponents to dismiss the collective judgement of so many credible organizations. While this network was challenging to maintain, it changed the nature of the debate and undoubtedly helped the bill pass.155

Save the Children New Zealand is the New Zealand branch of the international children’s rights organization Save the Children. As opposed to EPOCH, Save the Children NZ has a nationwide membership. The Corporal Punishment ban was first brought up in their national conference in 2003, before holding regional meetings on the topic with its members.156 The Governor General of New Zealand spoke at the conference challenging the use of corporal punishment; this speech persuaded members of Save the Children to support the ban and led to much public interest in the issue.157, 158 2 years after the conference, Save the Children commissioned an independent Researcher to research the views of children on corporal punishment, which found that children believed that parental violence was often not a correction tool but instead motivated by anger.This brought the important truth back to the fore of public debate, after it had been somewhat obscured by righteous parental claims.159

UNICEF New Zealand is the New Zealand branch of the international children’s rights organization UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund), which is a United Nations program. In 2004, UNICEF published Protect and Treasure New Zealand’s Children. This publication was endorsed by 24 well-reputed children’s organizations and was created to raise awareness for the need for a corporal punishment ban.160, 161 In 2006, UNICEF and the Office of the Children’s Commissioner funded the publication of Children are Unbeatable: 7 very good reasons not to hit children, a book and CD which argued against the use of corporal punishment. Rhonda Pritchard was one of the authors. She had long been an advocate and her argument was multifaceted and touched on children’s rights, physical and emotional harm, and the ineffectiveness of corporal punishment, among others things. Children are Unbeatable was designed as a resource for both children’s organizations and parents.162 As mentioned, the Families Commission eventually also helped fund the report.

Advocates from ethnic and religious communities

The Pasifika community were generally resistant to the corporal punishment ban, believing that corporal punishment was necessary and important. It was important for activists to overcome this barrier to reform because in 2006 Pacific people constituted a substantial proportion (6.42%) of New Zealand’s population.163 As “Pacific peoples have strong ties to their churches and may hold a deep belief in the importance of physical punishment”164 Reverend Nove Vailaau,“a significant Christian voice within the Samoan community” was an important advocate in this context. He came out in favor of the corporal punishment ban, justifying his opinion using material from the bible.165 Also influential was Fa’amatuani Tino Pereira who had been a broadcaster and was a community leader in Wellington while the ban proposal was circulating. He actively campaigned against corporal punishment, for instance by writing in 2004 that “There is nothing in our pre-missionary history to suggest any evidence of physical punishment as a way of raising children” referring to pre-colonial Samoa. He encouraged church leaders to support the ban.166 The New Zealand Herald columnist Tapu Misa was also a prominent Pacific media voice advocating for the ban.167

The Maori community in general only supported the ban late in the campaign, probably because they worried that it represented an opportunity for discriminatory prosecution.168 One group of iwi (which translates more or less to tribe) showed their support of the ban through a parliamentary submission and powerful press statement to accompany it, writing that “We want to dispel the myth that violence against children is normal or traditionally mandated, and work towards removing opportunities for violence to take place.”169 Maori Anglican church bishops declared their support for the ban just before it became clear that it would become law.170

Anglican Bishops passed a statement to the Prime Minister supporting the passage of the Bill, which was influential in reducing religious opposition.171

A failed repeal of the law

Deborah Morris-Travers, a former Member of the New Zealand Parliament, worked for Every Child Counts and was “closely involved in the campaign from 2004-2007”. She says that “after getting the law changed in 2007 there was a referendum to try and force the government to repeal the act. The referendum was highly skewed and confusing for many”. Advocates countered the efforts of proponents of repeal: “we ran a collective campaign to ensure the retention of the law”. This campaign was supported by advocacy groups including EPOCH New Zealand, Save the Children New Zealand and UNICEF New Zealand. The campaign’s website kept supporters up to date, advised supporters on how to ‘take action’ and contained resources such as this media kit which was written by Morris-Travers.172

Likewise, the law itself provided for regular review of its implementation, which proved extremely useful in blocking repeal efforts by certain groups by showing the law was being implemented appropriately.173 The New Zealand Police conducted these reviews.174

What worked well?

- The credible support network of EPOCH NZ made it hard to dismiss the arguments of key proponents. When challenges arose in debates, activists were able to quickly feed key supporters of law reform in parliament and other high level bodies with necessary and credible information to counter opposition. This information was hard for opponents to dismiss because of its broad support base.

- The use of credible research regarding the effects of corporal punishment made all advocates appear more credible and avoided polarizing the issue. The online resources made available by international groups such as the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment and domestic research provided crucial ammunition to advocates in New Zealand.175 New Zealand academics also spoke out in favor of the ban,176, 177 making it seem more legitimate.

Thanks to the availability of quality research, parliamentary submissions were highly credible. The authors of Unreasonable Force comment on the submissions in general:

The submissions that the authors have seen were well researched and carefully referenced as well as being clearly written and logically argued. The arguments put forward in these submissions were often based on children’s rights research findings on the negative outcomes of physical discipline for children. The review of international research into the disciplining of children conducted by the Children’s Issues Centre at the University of Otago in 2004 proved a valuable source of information for many submissions.178

Sharon Owen reiterates the importance of academic arguments, and notes that “they are without a doubt most useful when they are firmly based on the human rights of children to respect for physical and mental integrity and to a life free from violence etc.”179

This dispassionate method of persuasion also avoided polarizing the public debate further than fear-mongering opponents had already done.When making media appearances, advocates argued for reform using academic research to justify their points. The authors of Unreasonable Force believe that:

On reflection, adopting this policy was a critical decision- it avoided provoking needless criticism by the media; it was consistent with the image that respective organizations wished to project; and it encouraged the media to treat the issues more thoughtfully.180

- Utilizing all media opportunities meant that the pro-prohibition arguments easily came to mind. Advocates expressed convincing arguments for the ban whenever opportunity arose,181 which probably influenced politicians’ and the public’s opinions due to the availability heuristic;182 hearing these arguments often likely led them to believe they reflected the opinions of more members of the public than they actually did. Advocates ensured that celebrity supporters made media appearances when appropriate.183 The group Every Child Counts published a media guide to help other advocates.184

This availability argument also implies that generally speaking, it’s best not to give much air to opponents’ arguments or name specific opposition groups.

- Influencing politicians was more effective than changing public opinion. As discussed earlier in the case of Sweden, it appears that the law may play some role in legitimizing an opinion (as a form of social pressure). This suggests that it was a good idea for NZ activists to fight to get the law passed, because even though the majority of the public did not agree with it at the time, the democratic process was not going to be responsive enough to repeal it before public opinion changed in the law’s favor. In any case, the law was not repealed in New Zealand, although not through lack of effort from its opponents. Importantly, change appears to have stuck. In a recent Op Ed, New Zealand’s first Children’s Commissioner Ian Hassal writes:

In a Families Commission survey in 2009 only 9 percent of caregivers found smacking was an effective form of discipline…There may not be sufficient data points from these surveys to call the 35 year change in results a trend although another piece of information would support that conclusion and that is, surveys have repeatedly found younger parents to be less likely to be in favor of physical punishment than older ones…. I would say that since the 2007 law change, fewer children have experienced the pain and sense of betrayal that are a consequence of being hit by a parent. There may be a growing sense of respect for children and their right to be free from physical assault and the threat of assault.185

Note that in the face of overwhelming public disapproval, this tactic probably wouldn’t have worked; it was only because those in favor constituted a significant minority.

- Making it easy for prohibition supporters to contact politicians amplified their voice. Advocates encouraged individuals who supported the ban to meet with, email or write to politicians and established a website which made it easier to contact politicians. The authors of Unreasonable Force write that “Before this [website] was set up politicians reported that the number of emails opposing the Bill far exceeded the number in favor- this trend was reversed when supporters were provided with an easy way of contacting politicians”.186

- Positive relationships with members of the media allowed advocates to “inform the debate”.Advocates put substantial work into building positive relationships with well-reputed reporters and commentators who supported the ban, briefing these reporters when they knew an important event was coming up.187

- The internet expanded the reach of the campaign. Email allowed information to be easily transmitted, a blog allowed supporters to share their thoughts, and (as mentioned) the function allowing rapid emails to be sent made politicians more aware of the degree of support for the ban.188

- Advocates made the most of relevant controversies. The acquittal of a woman who had badly beaten her son played an important role in shifting public attitudes.189, 190 Like in Sweden, a case to provoke public outrage was a significant propellent for change.

What didn’t work well?

-

- Advocates were less successful at shifting public opinion—Language matters. One aspect of this that activist did not manage well was presenting the reform in a palatable manner. Journalists searching for attention-grabbing headlines may have been influenced (inadvertently or otherwise) by opponents of the bill who spread the idea that banning corporal punishment would criminalize responsible parents.With this perspective dominating media coverage the bill soon became known as the ‘anti-smacking bill’, even though public concern in banning corporal punishment had largely been provoked as a response to cases where parents were acquitted after having assaulted their children- the forms of violence being more severe than smacking. If activists had defined the parameters of the debate from the outset , for instance by attempting to spread the notion of an ‘anti-child assault bill’, this may have changed the nature of the debate.191The NZ Herald columnist Tapu Misa wrote after the implementation of that ban that:

Language matters, it seems. How much smoother the passage of Sue Bradford’s bill might have been if those opposed to it hadn’t got in first and framed it as an ‘anti-smacking bill’ which would usurp the rights of parents to lovingly discipline their children, rather than a long overdue attempt to stop abusive people hiding behind the law when they seriously hurt their children.192

For further social context and information, refer to Unreasonable force.

- Advocates were less successful at shifting public opinion—Language matters. One aspect of this that activist did not manage well was presenting the reform in a palatable manner. Journalists searching for attention-grabbing headlines may have been influenced (inadvertently or otherwise) by opponents of the bill who spread the idea that banning corporal punishment would criminalize responsible parents.With this perspective dominating media coverage the bill soon became known as the ‘anti-smacking bill’, even though public concern in banning corporal punishment had largely been provoked as a response to cases where parents were acquitted after having assaulted their children- the forms of violence being more severe than smacking. If activists had defined the parameters of the debate from the outset , for instance by attempting to spread the notion of an ‘anti-child assault bill’, this may have changed the nature of the debate.191The NZ Herald columnist Tapu Misa wrote after the implementation of that ban that:

What can animal activists learn?

The successes and failures of the New Zealand anti-corporal punishment movement should serve as lessons to animal advocates. It’s an example of advocacy on behalf of a disregarded group of persons, in which members of that group have not been the leading proponents. However, many proponents had previously been hit as children and so could speak of what it felt like in the first person. In New Zealand’s case this does not appear to have been an influential form of advocacy, but it’s important to recognize this difference may have implications for advocacy techniques.

The analysis above is not enough to determine with precision how many resources should be devoted to creating law changes. However, we have seen that laws criminalizing violence towards a particular group of persons do appear to delegitimize the form of violence by means of communicating the new non-violent social norm. Law change should not a priori be prioritized over other methods of communicating a (legitimate) social norm. Law change will probably eventually result from such an opinion change anyway. However, laws can also play another role. The non-punitive nature of the Swedish law with its two distinct types of measures was critical in reducing rates of corporal punishment. While the sanctions associated with animal rights laws should differ, this indicates that it is important to consider the law not only as a socially sanctioned rejection of a form of violence, but as a construct representing social and economic incentives to which individuals will respond. In other words, different sanctions will be suitable in different circumstances, and this matters. It’s possible that the sanction associated with the law may be significantly more important than its norm communication component in some cases–take economic sanctions for meat producers as an example–and vice versa in other cases.

Social norms regarding corporal punishment worldwide changed remarkably quickly following the law change in Sweden, and as discussed previously, this is probably not a coincidence. This suggests that some animal activists should spend most of their energies attempting to pass important animal rights legislation in countries/states/cities which are particularly open to it. Obviously, this positive international influence hinges on the law being deemed successful. Likewise, we saw in New Zealand that the corporal punishment ban became law in the face of a majority public opposition, but that opinions changed before the law could be reversed. Animal activists should therefore seek to make the most of the particularities of various political systems while trying to pass legislation which only a minority support.

The Swedish and New Zealand corporal punishment bans were spurred along by individual cases of extreme failing of current laws. We have seen that psychological mechanisms indicate that these events were probably highly influential, and animal activists should be sure to make the most of cases of animal mistreatment which surface. Caution seems appropriate here; most people are against extreme violence, so the debate could turn into a discussion about where to draw the line. Activists should be prepared with appropriate arguments to deal with this possibility.