Vegetarian Recidivism – 2015

This is an archived version of our report on vegetarian recidivism. You can read the most recent report here.

To determine the good done by convincing someone to change their diet to one that is better for animals, we need to know how long the changes will last. We investigate the general vegetarian recidivism rates in order to estimate the duration of the effects of any particular intervention.

Many organizations focused on helping farmed animals do so at least in part through asking institutions or individuals to reduce consumption of animal products. In the case of institutional changes, usually relatively few institutions are involved and institutional policy shifts are easily documentable. This makes it reasonable to determine how long the change lasts through checking in with the institutions involved on an individual basis.

However, in the case of individual changes, determining the average length that a change lasts for participants in a particular program would require large scale surveys conducted over many years. (Or, because individuals’ reports of their own food consumption can be unreliable, an even more expensive program of objective tracking (using independently verifiable information like sales patterns at school cafeterias), again lasting for years.) While performing some follow-up studies is clearly beneficial for understanding the impact of a specific program, no program-specific studies now exist that track results over an extended period of time, and it is unlikely that conducting such studies for every program or type of program would be cost-effective. Instead, we use general research on vegetarianism to estimate the long-term effects of programs directed at convincing individuals to change their diet.

Several studies exist focused specifically on vegetarian recidivism, the phenomenon of people eating a vegetarian diet at one time and then returning to an omnivorous diet. Most of these studies do not explicitly address other animal-product-limiting diets such as veganism, pescetarianism, or meat reduction. However, many have tacitly addressed these issues by recruiting self-identified vegetarians and former vegetarians. Self-identified vegetarians often do not fit the strict definition of vegetarian but generally do limit their animal product consumption in some way. Thus they have addressed many dietary habits, but without distinguishing between them. Also, studies that address vegetarian recidivism typically have not addressed the original motivations for becoming vegetarian and so the effects they show are not distinguished by the original cause of a person’s vegetarianism1. Therefore, our analysis will be unavoidably simplified.

“Self-Reported Vegetarians” Really Means “Animal-Product-Limiters”

The best information we have about the actual dietary habits of self-reported vegetarians comes from an analysis of data from the Continuing Survey of Food Intake by Individuals (CSFII), conducted by the US Department of Agriculture. This survey asked a large representative sample of Americans whether they identified as vegetarians, and on separate occasions asked detailed questions about what they had eaten in the past 24 hours. Of those who identified as vegetarians, 64% had eaten what the study considered a non-negligible amount of meat in one or both 24 hour periods. However, even the self-reported vegetarians who had eaten meat had eaten significantly less of it on average than the non-vegetarians had (about 74% as much, by weight), and the meat they ate was significantly more likely to be fish, suggesting that at least some may have technically been pescetarians.

Self-reported former vegetarians may also be, to some extent, animal-product-limiters. One study2 found that they reported following a variety of eating patterns that reduced meat consumption without excluding it completely. Another study3, however, did not find former vegetarians’ diets differed significantly from non-vegetarians’ in terms of animal consumption. Based on existing data, it is not possible to conclude that former vegetarians’ diets differ meaningfully from those of people who have never been vegetarian.

Dietary studies that rely on self-reports can only give us a general idea of a person’s true diet, especially if the self-reports are claims of identity categories like “vegetarian” and “vegan” rather than reports of the actual foods eaten. Studies that ask for self-reported vegetarianism or former vegetarianism should be taken to refer broadly to animal-product-limiting diets, unless the study explicitly says it omitted any self-reported vegetarians that also eat meat, such as a recent study by Faunalytics. Faunalytics asked whether participants identified as vegetarian or vegan and also asked them to report what food they currently consume. This two-tiered approach allowed Faunalytics to omit any self-reported vegetarians or vegans that also ate meat. Readers of the Faunalytics study can be fairly certain that participants in the vegetarian and vegan categories do not consume meat, but this cannot be generalized to all studies reporting about vegetarians and vegans.

Most Vegetarians Become Former Vegetarians

If most people who adopted a vegetarian or animal-product-limiting diet kept it up for the rest of their lives, the analysis of vegetarian recidivism might not be necessary. We could use well-established life expectancy figures to determine how many years of change to expect for each person who made a dietary change in the first place. However, this is not the case.

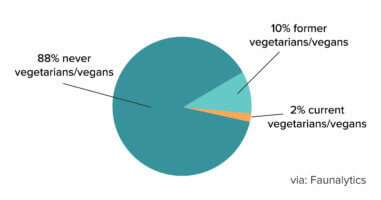

Studies suggest that the majority of vegetarians return to eating meat after a relatively short time. For instance, the Faunalytics study suggests that the number of former vegetarians4 in the US is five times higher than the number of current vegetarians. In their representative sample, 10% of respondents described themselves as former vegetarians, whereas only 2% were current vegetarians. In addition, CBS conducted a poll of a representative sample of the US population and found three times as many people described themselves as former vegetarians than as vegetarians. Although the margin of error of the poll allows for substantial variance in the ratio, it is likely that the number of former vegetarians in the United States is higher and closer to Faunalytics’ estimates for two reasons. First, people who were vegetarian for a short time several years before the survey may not have recalled it at the time of the survey, whereas people who were vegetarian at the time of the survey almost certainly did recall this, even if they were only vegetarian very briefly. Second, some of the people who reported being vegetarian at the time of the survey would not remain vegetarian for their whole lives, and the survey did not have any means of detecting this.

Overall, the evidence suggests that the vast majority of people who adopt dietary changes like vegetarianism, veganism, and other forms of animal-product-limiting eventually return at least some distance towards their former dietary habits. An intervention that changes an individual’s diet usually has only a temporary effect. To know the size of the effect, we need to know how long it lasts.

Figure 1. Raw Data on Vegetarian Diet Adherence from Faunalytics

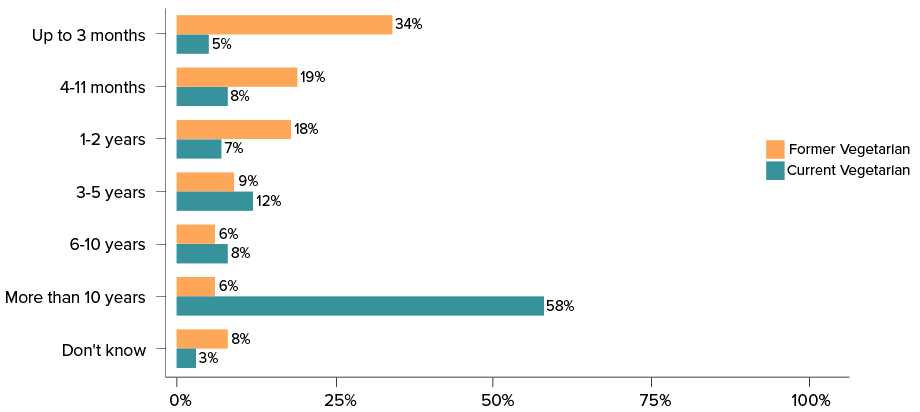

Estimates Based on Former Vegetarians

The easiest way to find out how long vegetarians typically remain vegetarian is to ask former vegetarians how long they were vegetarian for before they went back to eating meat. Since former vegetarians know how long they were vegetarian, they can accurately report it (at least within the limitations of accuracy of any self-report). Several studies have done this, but since each of them (except the Faunalytics study) specifically recruited former vegetarians, it’s likely they gathered non-representative samples of the total population of former vegetarians. However, since they recruited through different methods, these errors may cancel out somewhat when the estimates are taken together. Two studies5 reported mean lengths of vegetarianism for their samples of former vegetarians, which were 9 and 3.3 years. A third study6 did not collect exact lengths of time of vegetarian diets, but reported a median time of 3-5 years. Our estimate for the average was 4.5 years. Faunalytics’ study also did not collect exact lengths of time but reported a median time of 4-11 months (see Figure 1). Our estimate for an average time based on Faunalytics’ data was 2.8 years (+/- 0.40 years).

These estimates may err in several ways. First, people who were vegetarian for only a short time, especially who were vegetarian longer ago, may have been particularly unlikely to respond to recruitment attempts from any study. Second, respondents may have had a systematic bias to report longer or shorter periods than they really were vegetarian for, or to pick round numbers (which, depending on the actual distribution, could have biased the group estimate up or down or not at all). Finally, these are not estimates that directly speak to the question of how long the average person remains vegetarian, because some people may remain vegetarian for all or nearly all of their lives, and these people are either impossible or extremely difficult to find in a sample of former vegetarians.

Estimates Based on Current Vegetarians

Three of the studies7 mentioned above also surveyed self-identified vegetarians on how long they’d been vegetarian. While current vegetarians don’t know how long they will remain vegetarian, they can at least say how long it’s been so far. This is a useful lower bound, especially given that in all cases the mean times produced were longer than the mean times former vegetarians had been vegetarian. Specifically, one found a mean time of 9.7 years (vs 3.3 for former vegetarians). A second had a median time interval of 6-10 years, and our estimate for the average was 6.3 years (vs 3-5 and 4.5 for former vegetarians). The third study, from Faunalytics, reported a median of over 10 years (see Figure 1) and our estimate for the average was 14.1 years (+/- 1.5 years, vs 4-11 months and 2.8 years (+/- 0.40 years) for former vegetarians).

Although these numbers are already above those produced for former vegetarians, we know they’re lower than the reality. It would be valuable to get estimates that were closer to the real average times these participants would remain vegetarian. One way to do so is to assume not that they’ve talked to the Researchers on the last day they’ll be vegetarian, but on average about halfway through their period of vegetarianism. In a survey drawing randomly from the population, this would be a realistic assumption, though because these studies used nonrandom recruiting methods, it may not apply as well to them. In that case, the average length of vegetarianism would be about twice what the studies were able to observe—19.4, 12.6, and 28.2 years, respectively.

These estimates share all the problems of the estimates derived by talking to former vegetarians, except that instead of being unlikely to count people who are vegetarian for a long time, these estimates were especially unlikely to count people who are vegetarian for only a short time. Such people might be less likely to respond to recruitment efforts and also would only have a tiny window in which to do so as current vegetarians, so would be very unlikely to be involved in these studies.

Better Estimates

Ideally, an estimate for the mean length of time vegetarians stay vegetarian would follow a group of new vegetarians until none were left, recording how long each had remained vegetarian. However, this would be expensive. Another possibility would be to randomly poll the general population, asking each person whether they were or had ever been vegetarian, and if so for how long. Luckily, Faunalytics did something similar to this by polling a representative U.S. sample and asking vegetarian respondents if they have been (or were) vegetarian for 0-3 months, 4-11 months, 1-2 years, 3-5 years, 6-10 years, or more than 10 years. By combining data from former and current vegetarians, we obtained an overall average length of vegetarianism of 7.03 years (+/-0.80). We believe that this is the strongest estimate we have since it is derived from data that is representative of the U.S. population and a process that strictly defined vegetarianism as zero meat consumption.

A similar estimate of 6.2 years can also be obtained by patching together estimates from other studies, but since these estimates have considerable uncertainty due to unrepresentative samples, smaller sample sizes, and unknown diet specifics, we would find any value between 3.6 and 13.3 years defensible from this data.

Areas for Further Research

The existing data on vegetarian recidivism is incomplete. A long-term cohort study that follows vegetarians from the beginning to the end of their diet would be the best data for reliable population estimates. However, since this method would be expensive, a random sample from the population that asks for specific time lengths of vegetarianism would be a good alternative. Studies so far have also not reported on any differences in retention between self-reported vegetarians with different diets, and information on that topic would likely be immediately useful to groups working on creating change in individuals’ diets. Finally, our composite estimates for the mean length of vegetarianism, while useful, were ad hoc and lacking in rigorous statistical meaning; an expert statistician could revisit the data we have used and perform an analysis that would be more precise about the inferences that could be drawn.

Conclusions

Based on the available data, we believe that the average new vegetarian (or other animal-product-limiter, including vegans, pescetarians, and with less certainty adherents to meat reduction diets such as Meatless Mondays or Vegan Before 6) will retain their new dietary pattern for 7.03 years8 (+/- 0.80 years and a median of 1 year). It is possible but not substantiated that even after quitting their animal-product-limiting diet, former limiters will continue to eat somewhat fewer animal products than they had originally. Because the one study that included analysis based on participants’ motivations for vegetarianism did not find substantial differences in recidivism based on differences in motivation, it is likely that these findings are broadly applicable to any programs with similar target audiences, once differences in the rate at which people are convinced to go vegetarian are taken into account. Further research on a variety of points would be useful for reducing uncertainty and confirming that these results apply to the general population. However, we see limited value in multiple individual programs establishing the length of time that participants retain new dietary habits, because there is little evidence that the original cause of vegetarianism affects recidivism.

One non-representative retention study found minimal differences in vegetarian retention after three years between vegetarians who said that their primary reason for vegetarianism was health and vegetarians who said that their primary reason was ethics or animal rights. Other responses were available, but too few people selected them to draw any conclusions. Stahler, C. (2009). Do vegetarians and vegans stay vegetarian? The Vegetarian Resource Group.

[T]he majority of former limiters were occasional meat eaters, followed by regular meat eaters, meat avoiders, and pescatarians.” Haverstock, K., & Forgays, D. K. (2012). To eat or not to eat. A comparison of current and former animal product limiters. Appetite, 58(3), 1030-1036.

Compared to nonvegetarians and former vegetarians, who were similar, fewer vegetarians consumed any flesh foods at least weekly.” Barr, S. I., & Chapman, G. E. (2002). Perceptions and practices of self-defined current vegetarian, former vegetarian, and nonvegetarian women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102(3), 354-360.

Faunalytics reported findings from current and former vegans as well as larger numbers of current and former vegetarians. From this point on, we refer to the combined groups of vegans and vegetarians interviewed in that survey as current or former vegetarians for brevity. Faunalytics’ initial findings report most statistics for these combined groups.

Respectively, Herzog, H. (June 20, 2011). Why do most vegetarians go back to eating meat? [Blog post]. and Barr, S. I., & Chapman, G. E. (2002). Perceptions and practices of self-defined current vegetarian, former vegetarian, and nonvegetarian women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102(3), 354-360.

Haverstock and Forgays asked respondents to select the time range corresponding to the length of time they’d been vegetarian. Haverstock, K., & Forgays, D. K. (2012). To eat or not to eat. A comparison of current and former animal product limiters. Appetite, 58(3), 1030-1036.

Barr, S. I., & Chapman, G. E. (2002). Perceptions and practices of self-defined current vegetarian, former vegetarian, and nonvegetarian women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102(3), 354-360. and Haverstock, K., & Forgays, D. K. (2012). To eat or not to eat. A comparison of current and former animal product limiters. Appetite, 58(3), 1030-1036.

Until March 2015, we used the estimate of 6.2 years (with error bounds of 3.6 and 13.3 years) obtained from the studies available prior to the release of Faunalytics’ findings. Those figures are still reflected in calculations elsewhere on our site, though as we update other materials they will be replaced by the newer estimate.

This is an archived version of our report on vegetarian recidivism. You can read the most recent report here.

Statistics on Vegetarian Recidivism

Many interventions on behalf of farmed animals seek to convince individual people to reduce or eliminate their consumption of meat and other animal products. The effectiveness of such interventions is constrained by the length of time that those reductions in consumption last. Several existing studies address related questions. We synthesize their findings into a series of estimates for the length of time that the average person who responds favorably to persuasion to become vegetarian remains so. Most studies explicitly addressed only self-identified vegetarianism, but because self-identified vegetarians frequently follow other forms of meat-reduction in actual practice, we expect their results are relevant to other product limiters as well.

Several studies have produced information about the length of time that current or former vegetarians report having spent as vegetarians. These studies have not drawn their participants as a representative sample from the larger population, but instead have recruited self-identified current and former vegetarians online or in-person. Therefore, their samples may differ in a variety of ways from the overall population of vegetarians and former vegetarians. In particular, the proportion of former to current vegetarians is an artifact of the recruitment process, and participants may have identified more proactively as vegetarian (or formerly so) than would be expected of a sample drawn randomly.

The Haverstock and Forgays study includes partial data about the lengths of time participants in the study remained vegan, vegetarian, or pescetarian. For former abstainers Haverstock and Forgays asked for the length of their period of reduction, while for current abstainers Haverstock and Forgays asked how long they had been abstaining so far.

Responses were grouped by period. Haverstock and Forgays, Table 1 is shown below:

| Length of time as limiter | Current limiters | Former limiters |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 3 months | 2 | 1 |

| 4–6 months | 3 | 6 |

| 7 months to 1 year | 8 | 3 |

| 1–2 years | 33 | 9 |

| 3–5 years | 38 | 16 |

| 6–10 years | 45 | 6 |

| More than 10 years | 67 | 10 |

To form an estimate for mean time as a limiter, which Haverstock and Forgays do not do, we will assign each abstainer in the defined ranges a specific length of time corresponding to the midpoint of the range indicated by the response they gave, and those who reported abstaining for ten or more years will be assigned a time of ten years, since we have no plausible mean for the times included in that category.

The code that follows is the R code used in our analysis. If you would like a copy of the data used to replicate or extend our analysis, please contact us.

mean(forgays$time) ## [1] 5.949

tapply(forgays$time, forgays$type, mean) ## current former ## 6.321 4.517

Using our assumption, the mean reported abstention time in the study was almost six years; breaking it down further shows that former limiters reported a mean time of 4.5 years while current limiters reported a mean time of 6.3 years. These means are more informative than the whole-group mean, since we don’t expect the proportion of current to former limiters in this study to be representative of that in the overall population, due to the recruitment techniques used.

There’s a problem with the current limiter data, though: our estimate of their mean abstention time is biased markedly low, since they could in theory quit any time in the future and we’ve acted as if they will quit immediately after the survey. The simplest model for how the study obtained their abstention times is that each current abstainer Xi started abstaining at a personal time 0 and has some time ti at which they will resume consumption of animal products, and they entered the study at a random time t drawn uniformly from [0,ti]. In this case, the maximum likelihood estimate for ti is the time at which they took the survey, which we’ve used above, but it is a biased estimator. An unbiased estimator we could use instead is 2t. It is unbiased in the sense that, fixing ti, the expected value of 2t is ti. Unlike our other estimate, t, it will be too high roughly as often as it is too low.

The variable forgays$time2 is set to twice forgays$time for current abstainers and equal to forgays$time for former abstainers.

tapply(forgays$time2, forgays$type, mean) ## current former ## 12.643 4.517

This increases the difference in means between the two samples considerably. One reason for the difference is that the longer a person abstains from eating animal products, the more likely that person is to appear in a sample of current abstainers and the less likely to appear in a sample of former abstainers, if they are approached at a random time. In the case of this study there may be other reasons for the discrepancy related to the nonrandom recruitment of participants, in addition to random variation.

We calculate 95% bootstrap t confidence intervals for the group mean abstention times. Since the estimated data is less noisy than the real data, especially on the high end, we expect these intervals to be too narrow, particularly on the right side. However, they can provide a rough sense of which values for the true group means might lead to the data we see.

time.former mean.former N n Tstar for (i in 1:N) {

x Tstar[i] }

c(mean.former - quantile(Tstar, 0.975, names = F) * sd(time.former)/sqrt(n),

mean.former - quantile(Tstar, 0.025, names = F) * sd(time.former)/sqrt(n))

## [1] 3.546 5.581

For the current abstainers, we calculate an interval based on each estimator of their true abstention length.

time.current mean.current Tstar2 n2 for (i in 1:N) {

x Tstar2[i] }

c(mean.current - quantile(Tstar2, 0.975, names = F) * sd(time.current)/sqrt(n2),

mean.current - quantile(Tstar2, 0.025, names = F) * sd(time.current)/sqrt(n2))

## [1] 5.810 6.824

time2.current drop = T)

mean2.current Tstar3 for (i in 1:N) {

x Tstar3[i] }

c(mean2.current - quantile(Tstar3, 0.975, names = F) * sd(time2.current)/sqrt(n2),

mean2.current - quantile(Tstar3, 0.025, names = F) * sd(time2.current)/sqrt(n2))

## [1] 11.60 13.62

Taking every time in every 95% confidence interval above, our overall window of plausible mean times is (3.5463, 13.6155). On the low end, we assume almost everyone will abstain for a sufficiently short time that they will be much more likely to be a former abstainer than a current abstainer in a randomly-timed survey, and on the high end we assume the opposite and furthermore use the unbiased estimator for these respondents’ average time abstaining.

Other studies have not published as much distributional information, but may have more accurate estimates for the group mean times, because they collected the specific length of time each participant had abstained from eating meat, instead of time windows.

Childers and Herzog surveyed only ex-vegetarians online and got an average length of abstention of 9 years.

Barr and Chapman surveyed 90 current vegetarians and 35 former vegetarians, and found that the former vegetarians had been vegetarian for an average of 3.3 years while the current vegetarians averaged 9.7 years. Barr and Chapman also reported standard deviations (3.6 and 7.6 respectively), so we can compare these to the standard deviations of the samples in the Haverstock and Forgays study.

sd(time.former) ## [1] 3.528

sd(time.current) ## [1] 3.534

Our standard deviation for former abstainers in the Haverstock and Forgays sample is close to Barr and Chapman’s standard deviation for former vegetarians, perhaps because few former abstainers report having abstained for much longer than 10 years. (The maximum reported time for this group in Barr and Chapman’s study was 13 years.) On the other hand, the standard deviation we calculate for current abstainers in the Haverstock and Forgays study is much smaller than Barr and Chapman’s. This is probably because our methods for dealing with the substantial portion of this group that reported abstaining for more than 10 years were so clumsy. Barr and Chapman obtained specific reported lengths of abstention ranging up to 42 years for current abstainers, so their standard deviation is larger and probably much more accurate. Similarly, their mean reported length is higher and again probably more accurate.

We note that, for the reasons discussed above, an unbiased estimate for the average length of time the current vegetarians in Barr and Chapman’s study would spend as vegetarians would not be 9.7 years but 19.4 years. This is well outside our previous range of plausible estimates on the right-hand side, in agreement with our suspicions that our range is too narrow, especially in that direction.

We can also use general population studies that don’t ask for the length of time that the respondent has remained vegetarian to inform our estimates. One CBS poll in the United States found that, of respondents who were current or former vegetarians, 75% were in the “former” category. Theoretically, then, the average American who becomes a vegetarian for the first time will spend 75% of their life after that point as a former vegetarian and 25% as a current vegetarian. Specifically, 936 people responded to the poll; 6% self-identified as former vegetarians and 2% as current vegetarians. The 95% confidence intervals are 4.5-7.5% for the percentage of former vegetarians and 0.9-3.1% for the percentage of current vegetarians.

We can now replace our confidence intervals from the Haverstock and Forgays data with a single “plausible” interval that considers all the information we have available. While this is not a formally justifiable statistical technique, it will let us know roughly what range of true values for the length of time the average person remains a product limiter would be consistent with our present knowledge.

First, we will use a similar technique to produce our single best point estimate for the average period of vegetarianism.

We begin by producing single estimates for the mean abstention times of people surveyed as former or current abstainers by averaging the estimates for each category. Here, we use the low estimate for the current abstainers’ length of vegetarianism, to counter bias that may have been introduced by sampling methods. (People who respond to advertisements looking for current and former vegetarians may be more strongly identified as vegetarian and more likely to stick with it than self-identified vegetarians in the general population.)

Mean.former Mean.former ## [1] 5.606

Mean.current Mean.current ## [1] 8.011

Then, using the data from the CBS poll, we could infer that of the population of Americans who have abstained at some time, 75% are in the group best represented by surveys of former abstainers, while 25% are in the group best represented by surveys of current abstainers. (If the CBS poll had asked for mean lengths of time spent as vegetarian, 75% of the times they got would have been from former abstainers, and that poll was representative of the general population.) We would then produce for our estimate of the mean time of abstention:

0.75 * Mean.former + 0.25 * Mean.current ## [1] 6.207

Now, we extend this technique to find a lowest reasonable value and a highest reasonable value for the mean time of abstention. To find the lowest reasonable value, we assume that the correct percentages for the CBS poll to find were 7.5% former vegetarians and 0.9% current vegetarians, since all the studies found former vegetarians reported shorter times. Then of the current and former product abstainers in a general population poll, 89% would be former abstainers and 11% would be current abstainers. Furthermore, we will use our smallest plausible estimates for the mean abstention times of each of these subpopulations, 3.3 years for former vegetarians and 5.8097 for current vegetarians. This gives us our low estimate of

0.89 * 3.3 + 0.11 * (mean.current - quantile(Tstar2, 0.975, names = F) * sd(time.current)/sqrt(n2)) ## [1] 3.576

Similarly, for a high estimate, we assume the correct percentages for the CBS poll would have been 4.5% former vegetarians and 3.1% current vegetarians. The corresponding percentages, for the sample consisting only of former and current abstainers, are 59% former vegetarians and 41% current vegetarians. Then we use the highest estimate for average abstention time for each of these groups, 9 years for former vegetarians and 19.4 years for current vegetarians. (Here, we are also switching from the maximum likelihood estimator to the unbiased estimator. We don’t specifically expect this to give too high an estimate, but it does give us a less conservative estimate more appropriate for an upper bound.) Combining them, we get

0.59 * 9 + 0.41 * 19.4 ## [1] 13.26

Thus, we would consider any number of years in the interval (3.5761, 13.264) to be a true mean length of abstention consistent with our understanding. This interval is fairly wide, expressing some of our substantial uncertainty about how long the average vegetarian stays vegetarian. Even this broad question hasn’t been directly addressed by any of the studies we used, so additional uncertainty arises from sampling and design problems when the studies are used for this purpose. Furthermore, it is completely unknown whether people who choose to abstain from animal products due to the influence of organized vegetarian and vegan outreach efforts have different patterns of recidivism than the general populations.

This is an archived version of our report on vegetarian recidivism. You can read the most recent report here.

Resources

ACE. (2013). Vegetarian Recidivism Technical Supplement.

ACE. (2015). Faunalytics Data Analysis.

Alfano, S. (November 20, 2005). How and where America eats. CBS News.

Asher, K. et al. (2014). Faunalytics Study of Current and Former Vegetarians and Vegans.

Barr, S. I., & Chapman, G. E. (2002). Perceptions and practices of self-defined current vegetarian, former vegetarian, and nonvegetarian women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102(3), 354-360.

Haddad, E. H., & Tanzman, J. S. (2003). What do vegetarians in the United States eat? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(3), 626S-632S.

Haverstock, K., & Forgays, D. K. (2012). To eat or not to eat. A comparison of current and former animal product limiters. Appetite, 58(3), 1030-1036.

Herzog, H. (June 20, 2011). Why do most vegetarians go back to eating meat? [Blog post].