The Albert Schweitzer Foundation

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2020 |

| Current Version | November, 2021 |

Archived Version: November, 2020

What does the Albert Schweitzer Foundation do

The Albert Schweitzer Foundation (ASF) was founded in 2000. ASF primarily works in Germany, though they have a team in Poland as well. ASF works as a nonprofit (rather than making grants like a typical foundation). They work to improve animal welfare standards through their corporate outreach, corporate campaigns, and legal work. They also work with companies (distributors, producers, and restaurants) to promote plant-based alternatives to animal products. In addition, ASF works to build the capacity of the movement by organizing workshops and training sessions.

What are their strengths?

ASF works with corporations to implement welfare improvements for farmed chickens, such as through the European Chicken Commitment. ASF has also been expanding the work of their Aquaculture Welfare Initiative to improve the welfare standards of farmed fishes. We think that interventions targeting the welfare of chickens farmed for meat and farmed fishes may be particularly effective given the large number of animals being used and the neglectedness of advocacy on their behalf. Additionally, ASF’s strategic plan and planning process is particularly thorough and is inclusive of staff at all levels.

What are their weaknesses?

The cost effectiveness of ASF’s work toward increasing the availability of animal-free products and strengthening the animal advocacy movement seems slightly lower than the cost effectiveness of the other charities doing similar work that we evaluated in 2020. Additionally, we think that because of the hierarchical structure of their international work, ASF’s team in Poland seems to lack autonomy in terms of decision-making and strategy. We hope that ASF can hire a country director for their team in Poland and give them more autonomy to make decisions in their local context.

Why did the Albert Schweitzer Foundation receive our top recommendation?

ASF’s work seems highly effective at increasing the availability of animal-free products, improving farmed animal welfare standards, and strengthening the capacity of the movement. We are hopeful that their strategy and skills will lead to meaningful progress in Poland and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe, areas with relatively young animal advocacy movements. We believe that ASF’s work prioritizing corporate outreach on behalf of farmed fishes and chickens raised for meat is particularly promising, given the large number of farmed chickens and fishes killed and the neglectedness of advocacy on their behalf.

We find ASF to be an excellent giving opportunity because of their strong, impactful programs and their strategic approach to improving welfare standards for farmed animals.

How much money could they use?

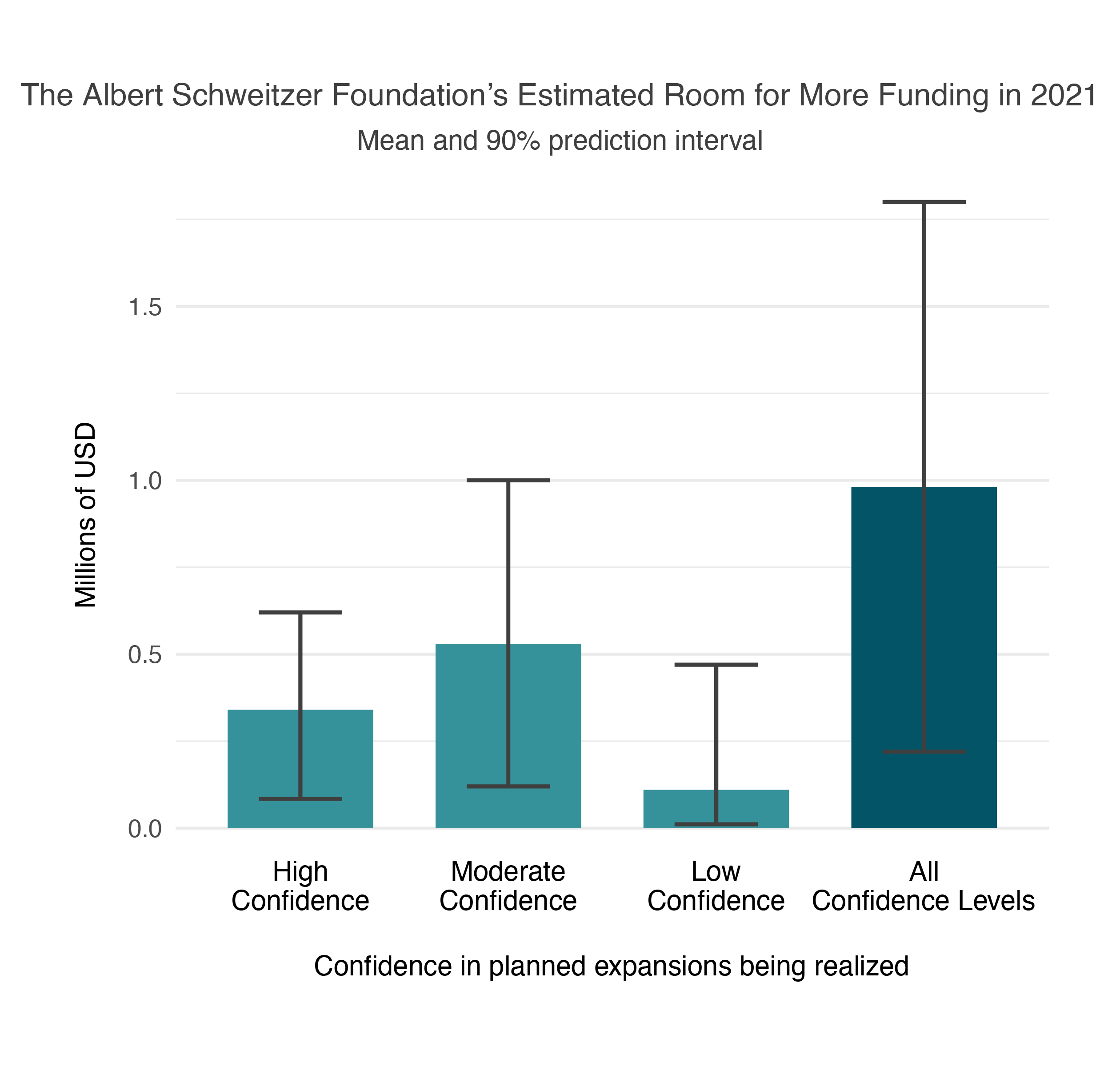

We estimate with high confidence that ASF’s room for more funding in 2021 is $0.34 million. Across all confidence levels, we estimate that ASF’s room for more funding in 2021 is $0.97 million. We expect that they would use additional funds to hire additional staff, expand their corporate outreach and campaign work, increase salaries, and expand to a third country.

The Albert Schweitzer Foundation has been one of ACE’s Top Charities since November 2018. They were one of ACE’s Standout Charities from December 2014 to November 2018.

How the Albert Schweitzer Foundation Performs on our Criteria

Interpreting our “Overall Assessments”

We provide an overall assessment of each charity’s performance on each criterion. These assessments are expressed as two series of circles. The number of teal circles represents our assessment of a charity’s performance on a given criterion relative to the other charities we evaluated this year.

| A single circle indicates that a charity’s performance is weak on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we evaluated: | |

| Two circles indicate that a charity’s performance is average on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we evaluated: | |

| Three circles indicate that a charity’s performance is strong on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we evaluated: |

The number of gray circles indicates the strength of the evidence supporting each performance assessment and, correspondingly, our confidence in each assessment relative to the other charities we evaluated this year:

| Low confidence: Very limited evidence is available pertaining to the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to the other charities. The evidence that is available may be low quality or difficult to verify. | |

| Moderate confidence: There is evidence supporting our conclusion, and at least some of it is high quality and/or verified with third-party sources. | |

| High confidence: There is substantial high-quality evidence supporting the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to the other charities. There may be randomized controlled trials supporting the effectiveness of the charity’s programs and/or multiple third-party sources confirming the charity’s accomplishments.1 |

Criterion 1: Programs

Criterion 1

Programs

When we begin our evaluation process, we consider whether each charity is working in high-impact cause areas and employing effective interventions that are likely to produce positive outcomes for animals. These outcomes tend to fall under at least one of the following categories: increased availability of animal-free products, decreased consumption of animal products, improvement of welfare standards, increased prevalence of anti-speciesist values, stronger animal advocacy movement, or direct help.

Cause Areas

The Albert Schweitzer Foundation (ASF) focuses exclusively on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we believe is a high-impact cause area.

Countries of Operation

ASF currently works in Germany and Poland.

Interventions and Projected Outcomes

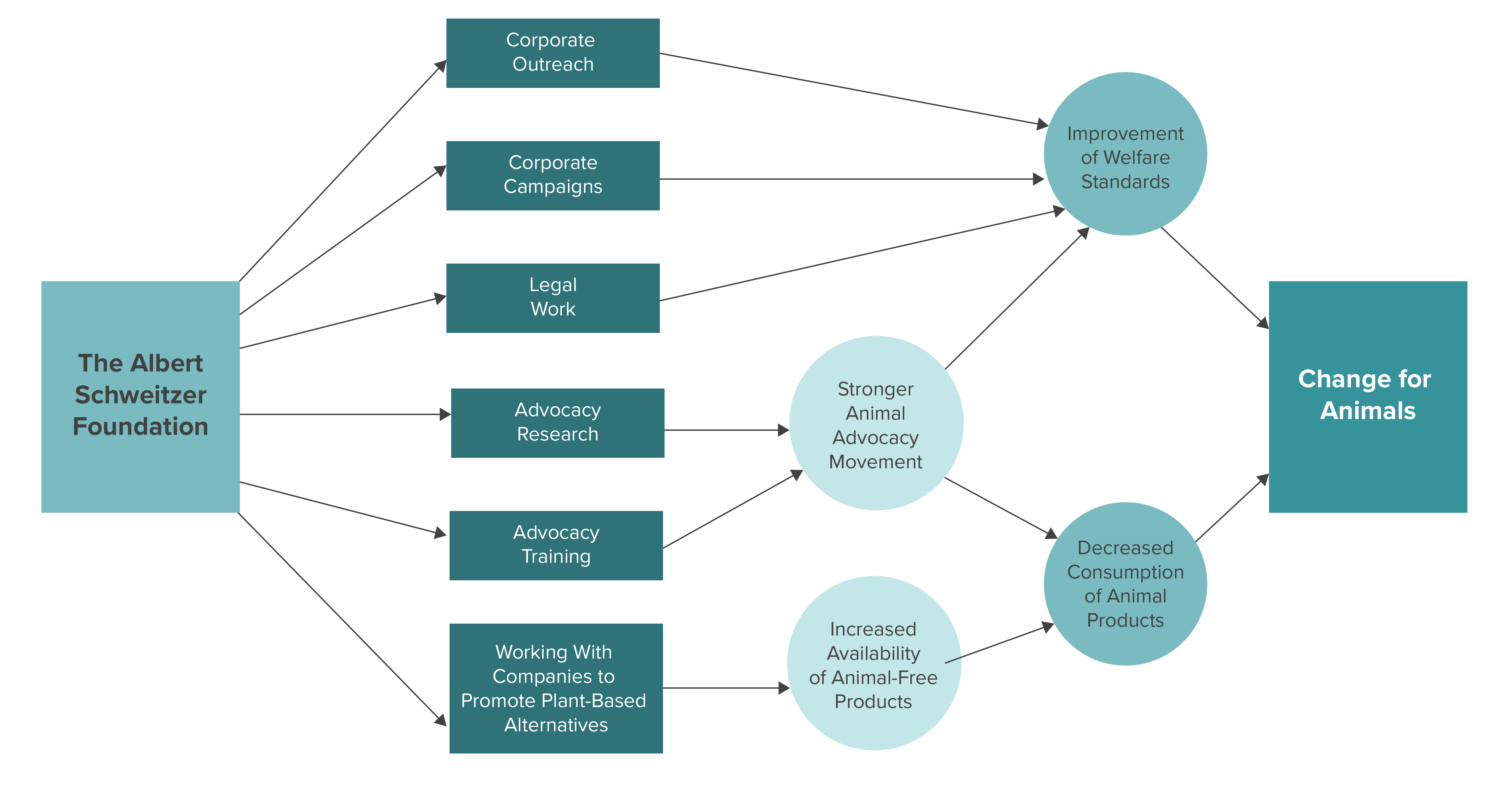

ASF pursues different avenues for creating change for animals: They work to improve welfare standards, increase the availability of animal-free products, and strengthen the animal advocacy movement.

To help communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

Below, we also describe the work that ASF does.2 Unless otherwise specified, we have sourced the information in this criterion from Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2020b). For each intervention, we provide an assessment of how effective we think that intervention is at achieving a given outcome (weak/moderate/high).3 These assessments are based on the available evidence and are determined through a vote and discussion among our researchers. We flag assessments in which we have particularly low confidence, i.e., if we know of little or no supporting research or expert opinions.

A note about long-term impact

Each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.4 The potential number of individuals affected increases over time due to population growth and an accumulation of generations of animals. Thus, we would expect that the long-term impacts of an action would be more likely to affect more animals than the short-term impacts of the same action. Nevertheless, we are highly uncertain about the particular long-term effects of each intervention. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew toward overemphasizing short-term effects.

Improvement of welfare standards

ASF works to improve animal welfare standards through their corporate outreach, corporate campaigns, and legal work. This work generally seeks to make incremental improvements to the conditions in which animals live, e.g., in factory farms. For farmed animals, welfare reforms generally only result in small improvements to their living conditions. However, this is balanced by the large numbers of animals who can be impacted, and there is some evidence to suggest that farmed animal welfare reforms are likely to be very cost effective in the short term.5 Overall, we believe that securing systemic change one corporation at a time is more tractable than lobbying for larger-scale legislative change.

ASF works with corporations to adopt better animal welfare policies and ban particularly cruel farming practices. They engage in corporate outreach and campaigns for companies to switch to higher welfare (but likely slower growing) breeds of chickens raised for meat and to commit to provisions on stocking density, lighting, and environmental enrichments, as outlined in the European Chicken Commitment. Such commitments may lead to higher welfare but also to more animal days lived in factory farms. We believe that influencing companies to switch to higher welfare breeds of chickens raised for meat is highly effective in improving welfare standards.

ASF also engages in outreach for companies to commit to minimum welfare standards for farmed fishes in Germany. Once established, they plan to use these standards as a benchmark for other European countries. We think that improving farmed fish welfare is a particularly promising cause area: It’s neglected, the scale of suffering is likely great, and there is potential for tractable interventions. We believe, with a low degree of confidence, that outreach to secure minimum farmed fish welfare standards is highly effective in improving welfare standards.

In addition to their focus on chickens raised for meat and farmed fishes, ASF also engages in corporate outreach and campaigns for companies to make cage-free egg commitments. Cage-free egg systems are believed to reduce suffering by increasing the space available to hens and providing them important behavioral opportunities, although during the transition process mortality may increase, and there is some risk that it may remain elevated.6 We believe that cage-free corporate outreach and campaigns are highly effective in improving welfare standards.

ASF also works to ensure that companies follow through with their welfare pledges. Many animal advocates are concerned that companies will fail to comply with welfare pledges;7 tracking companies’ compliance allows ASF and other advocacy organizations to exert pressure on companies that seem likely to fail to meet their commitments. We believe that monitoring companies’ compliance with welfare standards is highly effective in improving welfare standards.

In collaboration with other organizations, ASF files lawsuits to achieve court rulings stating that common practices in factory farming are in violation of Germany’s constitutional animal welfare law. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we expect its effects to be particularly long-lasting. We think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to have an impact on a large number of animals and that they are more likely to be followed through on than similar corporate campaigns. We believe that working to encode animal welfare protections into law is highly effective in improving welfare standards.

Increased availability of animal-free products

Increasing the quality and availability of plant-based foods may help to create a climate in which it is easier for individuals to reduce their use of animal products.

ASF works with companies (distributors, producers, and restaurants) to promote plant-based alternatives to animal products. For example, they publish industry rankings to compare the vegan selection available at retailers, pizza delivery companies, and bakery chains. We believe that working with companies to increase the range and accessibility of plant-based foods is highly effective in increasing the availability of these products.

Stronger animal advocacy movement

Working to strengthen the animal advocacy movement through capacity- and alliance-building projects can have a far-reaching impact. Capacity-building projects can help animals by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations, while building alliances with key influencers, institutions, or social movements can expand the audience and impact of animal advocacy organizations and projects. ACE’s 2018 research on the way that resources are allocated between different animal advocacy interventions suggests that capacity building and building alliances are currently neglected relative to other interventions aimed at influencing public opinion and industry. ASF’s capacity-building work includes engaging in animal advocacy research and organizing workshops and training sessions.

ASF researches and compiles animal welfare science literature on various topics including veterinary care, animal product production, and public demands to raise welfare standards.8 This type of research can help inform different programs at ASF and other animal advocacy organizations. We believe that producing advocacy research is highly effective in strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

ASF also helps advocates increase their impact by organizing workshops on burnout prevention and working with organizations to improve their management practices.9 Through these workshops, they aim to improve the movement’s understanding of effective advocacy tactics and internal operations. We believe that professional training (e.g., relating to management and operations) is highly effective in strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

Criterion 2: Room for More Funding

Criterion 2

Room for More Funding

We look to recommend work that is not just high-impact, but also scalable. Since a recommendation from us could lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding, we look for evidence that the charity will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. To estimate a charity’s room for more funding, we not only consider the charity’s existing programs and potential areas for growth and expansion, but also non-monetary determinants of a charity’s growth, such as time or talent shortages.

Since we can’t predict exactly how an organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative rather than definitive. This year, our estimates are especially uncertain, as we do not know the consequences of COVID-19 on financials. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect or that they could come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. At midyear, we check in with each recommended charity about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented below to indicate whether we still expect them to be able to effectively absorb additional funding at that point.

Financial History and Financial Sustainability

An effective charity should be financially sustainable. Charities should be able to continue raising the funds needed for their basic operations. Ideally, they should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support. Charities should also hold a sufficient amount of reserves.

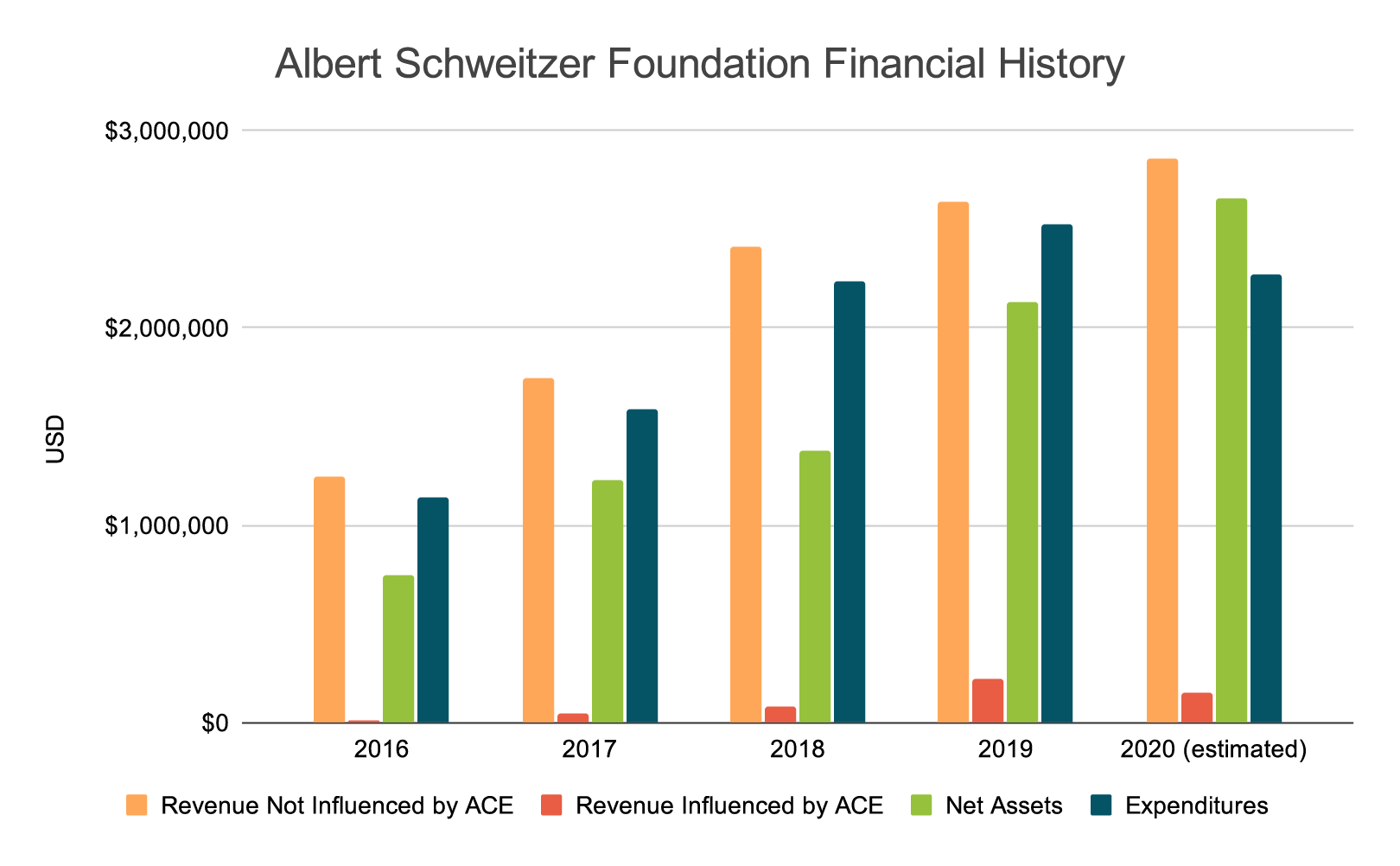

The chart below shows ASF’s recent revenues, assets, and expenditures.10 The financial information for 2019 and the first six months of 2020 was reported by the charities during this year’s evaluation process,11 the financial information for earlier years was acquired from various sources, and the values for 2020 are estimated based on the first six months of 2020. ASF’s revenue has grown steadily in the past few years. They received a large donation (about 27% of their annual revenue) in 2019, and they expect a grant of similar size in 2020. ASF has received funding influenced by ACE as a result of their prior recommended charity status. From 2016 to 2019, donations reportedly influenced by ACE accounted for 4.3% of ASF’s total revenue. We estimate that in the first half of 2020, ACE-influenced donations may account for 3.3% of ASF’s revenue.12 With about 117% of their current annual expenditures held in net assets, we believe that ASF holds a sufficient amount of reserves.

Planned Future Expenditures

Below we list ASF’s plans for expansion for 2021.13 For each plan, we provide an estimate of the expenditure as well as a confidence level, which indicates how confident we are that the plan can be realized in 2021.14 For staff salaries, we estimated the number of staff ASF could hire by considering the number of existing staff they have and the number of staff they have plans to hire in 2021. For the corresponding costs, we made salary estimates based on information about the job’s seniority, type, and location using data from current and past job postings whenever possible.15 We also factored in additional costs incurred as part of the hiring process. We estimated non-staff-related costs for each charity’s plans for expansion16 based on their 2019 program expenditures;17 in some cases, we also considered ASF’s estimations of their future expenditures18 and/or our impressions of how much the expansions would cost.19 Additionally, we accounted for an estimate—based on a percentage of the charity’s current annual budget—of possible unforeseen expenditures.

| Planned Expansion | Estimate of Expenditure20 | Confidence Level in Realizing Expansion21 |

| Hiring 14 additional staff | $0.31M to $1.4M | High (35%) and moderate (65%) |

| Expanding corporate campaigns | $6.6k to $92k | High (35%) and moderate (65%) |

| Expanding corporate outreach work | $19k to $0.27M | High (35%) and moderate (65%) |

| Increasing legislative work | $17k to $0.10M | High (35%) and moderate (65%) |

| Increasing salaries in Poland | $4.9k to $20k | High (35%) and moderate (65%) |

| Increasing salaries in Germany | $91k to $0.18M | High (35%) and moderate (65%) |

| Increasing IT infrastructure | $0.50k to $20k | High (35%) and moderate (65%) |

| Expanding to a third country | $8.1k to $83k | High (35%) and moderate (65%) |

| Holding a legal conference in an academic institute | $0k to $15k | High |

| Commissioning reports from professors | $5k to $30k | High |

| Hiring consultants on fundraising | $15k to $0.12M | High |

| Possible additional expenditures22 | $22k to $0.45M | Low |

Estimated Room for More Funding

We estimated ASF’s room for more funding for 2021. For this, we relied on an estimate of their predicted revenue for 2021. ASF has received funding influenced by ACE as a result of their prior recommended charity status, which we subtracted from past values when estimating the predicted revenue. We estimate that ASF’s revenue in 2021 will be $3.4 million or within the 90% prediction interval [$3.1M, $3.8M].23 ASF’s own prediction of their 2021 revenue ($3.3M) lies within the predicted interval.

We estimated ASF’s room for more funding for 2021. For this, we relied on an estimate of their predicted revenue for 2021. ASF has received funding influenced by ACE as a result of their prior recommended charity status, which we subtracted from past values when estimating the predicted revenue. We estimate that ASF’s revenue in 2021 will be $3.4 million or within the 90% prediction interval [$3.1M, $3.8M].23 ASF’s own prediction of their 2021 revenue ($3.3M) lies within the predicted interval.

Using our predictions of future revenue, ASF’s room for more funding was estimated via Guesstimate. Note that when ACE estimates a charity’s room for more funding, we are estimating the amount of funding that the charity could use on top of their predicted, regular funding in the coming year.

The chart shows ASFs room for more funding in 2021 distributed across our three confidence levels. For donors influenced by ACE wishing to donate to ASF, we estimate that ASF’s room for more funding in 2021 is $0.34 million (90% prediction interval: [$82k, $0.62M]) with high confidence. Overall, we have some confidence that ASF has room for $0.97 million (90% prediction interval: [$0.22M, $1.8M]) in additional funding in 2021. We believe that ASF’s room for more funding relative to the size of their organization is of average size compared to the other charities we evaluated this year. We also believe that their absolute room for more funding is of average size relative to the funding we influence through our recommendations. Given the impact a recommendation may have on a charity’s funding, we base our rating of performance in this criterion on the latter assessment.

Criterion 3: Cost Effectiveness

Criterion 3

Cost Effectiveness

A charity’s recent cost effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component in understanding how cost effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources over the past 18 months and compare that to the outcomes they have achieved in each of their main programs during that time. We have used an approach in which we qualitatively analyze a charity’s expenditures and key results and compare them to other charities we are reviewing this year.

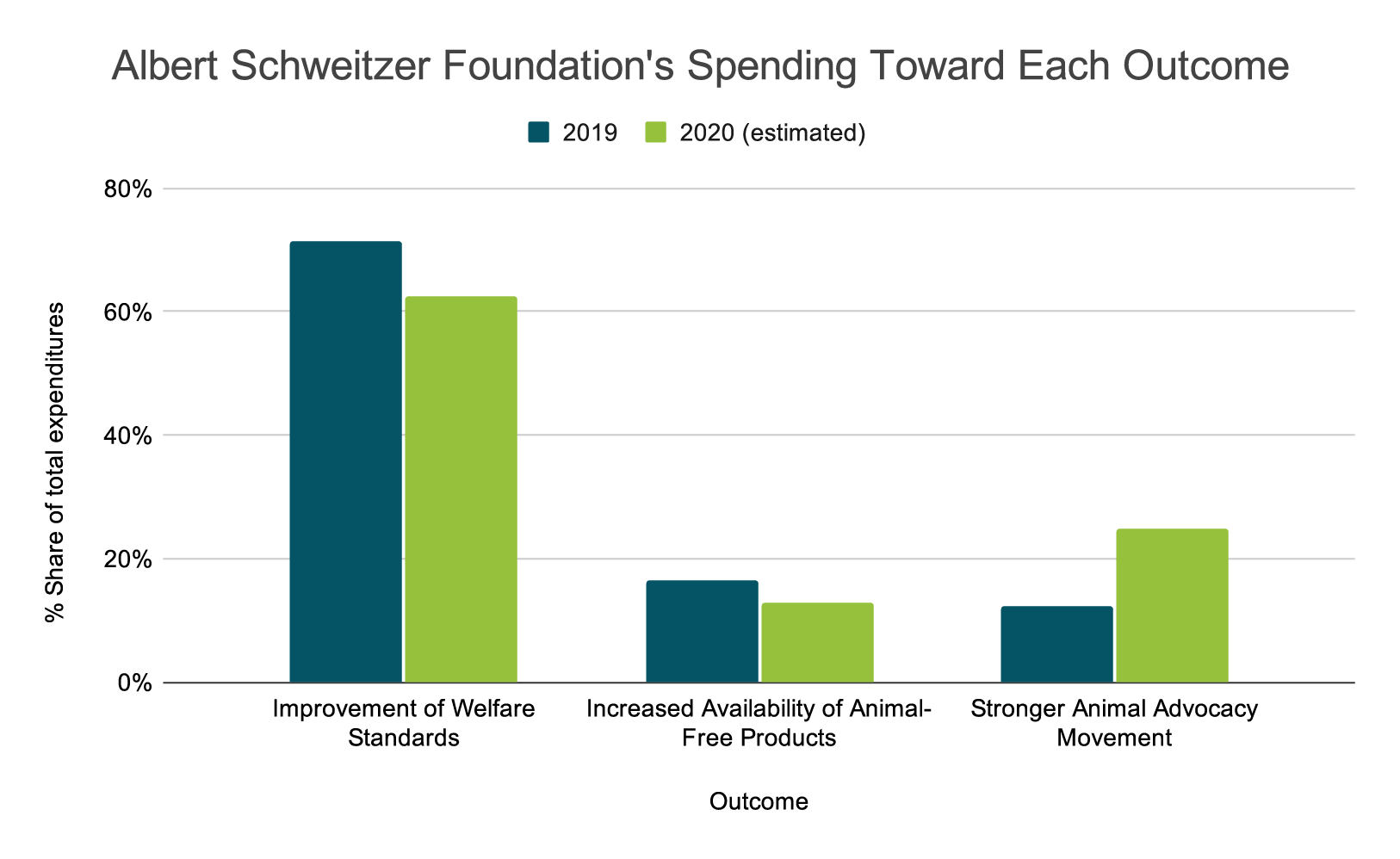

We categorized the charity’s programs into different outcomes—improvement of welfare standards, increased availability of animal-free products, decreased consumption of animal products, increased prevalence of anti-speciesist values, and stronger animal advocacy movement. Then, for a given outcome, we compared the charity’s key results and expenditures from January 2019 to June 2020 to other charities we evaluated in 2020 and gave our assessment of how cost effective we think their work toward that outcome has been.

Improvement of Welfare Standards

ASF engages in three programs that we have categorized as contributing to the improvement of welfare standards—corporate outreach, corporate campaigns, and legal work. As the resource usage and reported results of each program are distinct, we have kept them as separate categories in our analysis.

Key results and use of resources

Below is our estimated resource usage for ASF’s programs focused on improvement of welfare standards, January 2019–June 2020. In this section, we have only included what we believe are the key results of each program. For a full list of results and resource usage, see Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2020a).

- Secured 20 welfare commitments for chickens farmed for meat (15 of which ASF reportedly secured alone, 5 of which ASF secured in cooperation with other groups)

- Secured 19 cage-free egg commitments (alone and in cooperation with other groups)

- Two retailers joined their Aquaculture Welfare Initiative24

- In cooperation with other groups, convinced two retailers to end the sale of live fishes25, 26

- Worked with seven retailers to improve their animal welfare policies

Expenditures27 (USD): $1,310,981 (of program total $1,872,831)28

- Won three welfare campaigns for chickens raised for meat against companies (all in cooperation with other groups)

- Won four cage-free campaigns against companies (all in cooperation with other groups)

Expenditures29 (USD): $761,789

- Provided strategic assistance that contributed to the success of a case against plans to reopen a large pig farm in Germany (in cooperation with other organizations)

- Partial win against the Federal Chancellery of Germany in the first instance about access to documents on their animal protection work

- Won a case against the German Ministry of Agriculture about access to documents on the issue of killing male chicks

- Reached second instance in court case to end the worst practices in turkey production

Expenditures30 (USD): $436,585

Table: Estimated number of animals affected31 by corporate commitments, January 2019–June 2020

| Number affected per year by commitments (corporate campaigns) | Number affected per year by commitments (corporate outreach) | |

| Caged hens | 12M–130M | 0.44M–3.2M |

| Chickens raised for meat | 5.5M–610M | 3.3M–360M |

Evaluation of cost effectiveness

ASF’s corporate outreach and corporate campaigns programs focus on securing commitments to improve welfare standards for farmed animals. In the past 18 months, ASF has reported securing 19 cage-free commitments and 20 commitments for chickens raised for meat through their corporate outreach program, and an additional four cage-free commitments and three commitments for chickens raised for meat through their corporate campaigns program. After factoring in the proportional responsibility that ASF had for securing these commitments, we estimate these commitments may affect 45–890 million animals once implemented.

A detailed analysis of these estimates can be found in this Guesstimate model. Our estimates take into account the uncertainty about the rates with which companies follow through on their commitments. We are not aware that ASF actively follows up on commitments. However, ASF secured a share of their cage-free commitments in Germany, where it seems that companies have preferred to implement their cage-free commitments very quickly, often prior to announcing them. This is a distinct advantage over the U.S., for example, where companies have made commitments often with deadlines 5–10 years after the commitment, which leaves the risk that they will not be followed through on without continued campaigning.32 After accounting for all of their key results and expenditures, we think the cost effectiveness of ASF’s work in their corporate campaigns program seems similar to the average cost effectiveness of other similar programs working toward improving welfare standards we have evaluated this year.

ASF’s corporate outreach program has also secured two commitments from retailers to ban the sale of live fishes. As fishes are currently one of the most neglected and largest of the farmed animal groups, it may be that their work in this area is particularly cost effective in comparison to corporate campaigns targeting other animal groups. ASF also organizes the Aquaculture Welfare Initiative. After accounting for all of their key results and expenditures, we think the cost effectiveness of ASF’s work in their corporate outreach program seems slightly higher than the average cost effectiveness of similar programs other charities we evaluated this year. After accounting for all of their key results and expenditures, we think the cost effectiveness of ASF’s work in their corporate outreach program seems slightly higher than the average cost effectiveness of other similar programs working toward improving welfare standards we have evaluated this year.

ASF’s legal work program focuses on improving welfare standards for farmed animals by fighting for changes to German national law. The majority of their results are indirect, and as such, it is difficult to make an assessment of their cost effectiveness. For example, they recently achieved a partial success toward improved rearing conditions for turkeys and won a case against the German Ministry of Agriculture about access to documents on the issue of killing male chicks.33 We believe that changes in national law can be comparatively more cost effective than other legal advocacy work, but we are still particularly uncertain in our assessment of cost effectiveness given that the outcomes of this work for animals is more indirect. After accounting for all of their key results and expenditures, we think the cost effectiveness of ASF’s work in their legal work program seems similar to the average cost effectiveness of other similar programs working toward improving welfare standards we have evaluated this year.

ASF has reported to us that in light of COVID-19, pressure campaigns have been paused and outreach work has been refocused to less impacted companies, such as retailers. They have also shifted to highlighting pandemic and other health risks.

Overall, we think the cost effectiveness of ASF’s work toward improving welfare standards seems slightly higher than the average cost effectiveness of other charities’ work toward this outcome we have evaluated this year.

Increased Availability of Animal-Free Products

ASF engages in one program that we have categorized in part as contributing to increased availability of animal-free products—corporate outreach.

Key results and use of resources

Below is our estimated resource usage for ASF’s program focused on increased availability of animal-free products, January 2019–June 2020. In this section, we have only included what we believe are the key results of each program. For a full list of results and resource usage, see Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2020b).

- Distributed 589 plant-based cooking guides34

- Published two rankings—one of bakeries and one of retailers—indicating their availability of vegan products, as well as a third ranking in cooperation with Anima International

- Created an online tool for vegan rankings that five other groups used (three rankings published so far)

- Supported the action week “Grandma Cooks Vegan” by a university caterer centered around traditional home cooked meals

Expenditures35 (USD): $561,849 (of program total 1,872,831)36

Evaluation of cost effectiveness

As part of their corporate outreach program, some of ASF’s outcomes contribute to increasing the availability of animal-free products. In the past 18 months, they have distributed 590 plant-based guides to caterers and published three vegan rankings of caterers and companies. They have also made their vegan ranking platform available for others to set up their own rankings (three groups have published their own rankings so far), which seems like a good way to increase the cost effectiveness of that part of the program.

Overall, we think the cost effectiveness of ASF’s work toward increasing the availability of animal-free products seems slightly lower than the average cost effectiveness of other charities’ work toward this outcome we have evaluated this year.

Stronger Animal Advocacy Movement

ASF engages in one program that we have categorized as contributing to strengthening the animal advocacy movement—capacity building.

Key results and use of resources

Below is our estimated resource usage for ASF’s program focused on strengthening the animal advocacy movement, January 2019–June 2020. In this section, we have only included what we believe are the key results of this program. For a full list of results and resource usage, see Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2020b).

- Hosted a workshop on burnout prevention and a roundtable on quality assurance for other animal advocacy groups

- Worked with experts to host workshops on nonviolent communication and organizational culture

- Organized the Animal Center (a thematic center focused on farmed animals) at the Women’s Congress in Poland

Expenditures37 (USD): $588,336

Evaluation of cost effectiveness

Building a stronger animal advocacy movement encompasses a broad category of outcomes for animals that are typically indirect, and as such, it is difficult to make an assessment of their cost effectiveness. ASF’s capacity-building program focuses on providing professional training to ASF staff and other charities. In the past 18 months, they have hosted workshops on burnout prevention, quality management, and other topics. They also organized the Animal Center at the Women’s Congress in Poland.

Overall, we think that the cost effectiveness of ASF’s work toward strengthening the animal advocacy movement seems slightly lower than the average cost effectiveness of other charities’ work toward this outcome we have evaluated this year.

Criterion 4: Track Record

Criterion 4

Track Record

Information about a charity’s track record can help us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments, which is information that cannot always be incorporated into our other criteria. An organization’s track record is sometimes a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences between two charities.

In this section, we evaluate each charity’s track record of success by considering some of the key results that they have accomplished prior to 2019.38 For charities that operate in more than one country, we consider how they have expanded internationally.

Overview

ASF was founded in 2000. They have been working on corporate outreach for at least 12 years, building a strong track record of success in achieving cage-free commitments in Germany, where most large-scale companies have stopped using eggs from caged hens. Their track record of success in achieving corporate commitments targeting chickens raised for meat and fishes is shorter than their work on cage-free commitments. ASF has worked on their capacity-building program for eight years and for three years on their legal program.

Key Results Prior to 201939

Below is a summary of ASF’s programs’ key results prior to 2019, ordered by program duration (with the longest-running programs listed first). These results were reported to us by ASF, and we were not able to corroborate all their reports.40 We do not expect charities to fabricate accomplishments, but we do think it’s important to be transparent about which outcomes are reported to us and which we have corroborated or verified independently. Unless indicated otherwise, the following key results are based on information provided by Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2020b).

Note that many of these results have been achieved in collaboration with other organizations and individuals.

Key Results:

- Achieved, in collaboration with other organizations and individuals, multiple corporate cage-free commitments in a large share of the German food industry

- Published a paper on the end of beak trimming in Austria (2010)

- Launched the Aquaculture Welfare Initiative with the support of German retailers (2018)

- Worked with German retailers on publishing and updating their animal welfare policies

- Set up daughter foundation in Poland (2017),41 which achieved 32 cage-free commitments (2018)42

Our Assessment:

We think that through this program, ASF has strongly contributed to improving the welfare standards of farmed animals in Germany, especially chickens used for eggs who’ve stopped being raised in battery cages. Since corporate cage-free commitments are often achieved in cooperation with others, it is very difficult to determine the magnitude of this program’s impact. However, if implemented, these commitments are likely to affect a large number of animals, especially chickens.

Key Results:

- Conducted workshops for ASF and other NGOs on burnout prevention and stress

- Improved ASF’s “Even If You Like Meat” brochure in cooperation with a university (2014)

- Developed a fact sheet on the topic of vegan-organic produce for retailers

Our Assessment:

We think that through this program, ASF has somewhat contributed to strengthening the animal advocacy movement by decreasing stress and improving burnout prevention in ASF and other organizations, and by creating resources that might be useful for other advocates.

Key Results:

- Successfully defended a court case in Germany on the legality of undercover investigations when animal welfare law is broken (2018)43

- Funded a lawsuit that led to the resignation of the Minister of Agriculture in the State of North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany, and the replacement by a candidate with policies more friendly to animal welfare (2018)

- Co-funded a lawsuit that prohibited an investor to relaunch a large factory farm in eastern Germany

Our Assessment:

We think that through this program, ASF has moderately contributed to improving animal welfare in Germany by creating legal actions to facilitate undercover investigations in the country. It also has had effects at the local level by funding lawsuits against animal cruelty and preventing the construction of a factory farm.

Key Results:

- Won a broiler welfare campaign against major food manufacturer Dr. Oetker (2018)44

- Participated in an OWA international cage-free campaign against Marriott (2018)45 (Hyatt followed suit shortly after)

Our Assessment:

We think that through this program, ASF has somewhat contributed to improving the welfare standards of farmed animals in Germany by achieving corporate commitments to improve the conditions of chickens farmed for meat and eggs. Since corporate commitments are often achieved in cooperation with others, it is very difficult to determine the magnitude of this program’s impact. However, if implemented, these commitments are likely to affect a large number of animals, especially chickens.

International Expansion

We think that expanding internationally can be a way for effective charities to increase their impact. By introducing effective programs into countries where similar work is not being done—or where similar work is being implemented relatively ineffectively—those charities can expand their audience and impact. That said, international expansion needs to be handled thoughtfully; in addition to the strategic value of expanding to a new country, charities should consider the linguistic, social, political, economic, and cultural factors that could pose challenges. We think that charities should work carefully with local activists46 during any expansions and that organizations founded in Western countries should consider the historical effects of colonialism in their expansion to non-Western countries.

ASF was founded in Germany in 2000. They expanded to Poland in 2017. When expanding internationally, they aim to identify areas where they feel they can add the most value to the movement. They prioritize their expansion based on whether that country would benefit from having additional corporate outreach/campaign work being carried out there, and whether they feel ready to expand into that country after considering how similar the cultural, political, and legal systems are to countries they currently operate in.47 Following their expansion into Poland, they identified a need to restructure their leadership to create more capacity for internationalization work, so they postponed considering further expansions until they had enacted those changes.

ASF reports that leadership from both their Germany and Poland offices are responsible for decision-making regarding local programs carried out by the office in Poland.48 At the moment, the Director of Internationalization in Germany makes decisions for Poland because they don’t have a Country Director for their office there. Leadership from Germany have discussions about projects or campaigns with the local team in Poland on an ongoing basis and before launching new projects. Although decision-making about local programs in Poland seems to be a responsibility shared by leadership from both countries, the strategy and direction of Poland’s office is led by the President and the Director of Internationalization in Germany with input and suggestions from Poland’s employees. Note that the Poland branch does not have an independent board, and it’s not financially independent either; because of their lack of fundraising capacity, they require funding from the German foundation.49

Overall, we think that ASF has been strategic in their international expansion and has avoided expanding too quickly to other countries. However, because of the hierarchical structure of their international work, there seems to be a lack of autonomy of the subsidiary, both financially and in terms of decision-making, strategy, and direction. We hope ASF can hire a country director for Poland soon and give them more autonomy to make decisions about programs in their local context.

Criterion 5: Leadership and Culture

Criterion 5

Leadership and Culture

Leadership directly affects an organization’s culture, performance, and effectiveness. Strongly-led charities are likely to have a healthy organizational culture that enables their core work. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership to describe the culture they try to foster, as well as potential areas of improvement. We review each charity’s human resource policies and check that they include those we believe are important. We also send a culture survey to the staff of each charity.50, 51

Key Leadership

In this section, we describe each charity’s key leadership and assess some of their strengths and weaknesses.

Leadership staff

- President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO): Mahi Klosterhalfen, involved in the organization for 12 years

- Director of Internationalization: Silja Kallsen-MacKenzie, involved in the organization for 10 years

- Director of Campaigns: Carsten Halmanseder, involved in the organization for 9 years

- Director of Corporate Outreach: Luisa Böhle, involved in the organization for 6 years

- Director of Communications: Diana von Webel, involved in the organization for one year

About 86% of respondents to our culture survey agreed that ASF’s leadership is attentive to the organization’s strategy. Most respondents agreed that their leadership promotes external transparency (81%) and internal transparency (76%). Some respondents commented that ASF is improving internal transparency but that there is room for further improvement.

Recent leadership transitions

ASF had transitions in their leadership team recently. They changed their dual leadership to single leadership; they now have one CEO instead of two people sharing those responsibilities. The former director and some former employees affected by this change will form a new, independent organization, and ASF will give them full access to the work they have done while at ASF.52 In the last year, ASF also hired a Director of Communications and created the position of Director of Internationalization.

Board of Directors

ASF’s Board of Directors consists of three members, including CEO and President Mahi Klosterhalfen. We think that the CEO being part of the board can restrict the board’s capacity to oversee the organization from a more independent and objective perspective. We consider the board’s lack of independence to be a weakness.

Members of ASF’s Board of Directors

- Mahi Klosterhalfen (President of the Board): animal advocate with Dipl. Kfm., the German equivalent of an MBA

- Rolf Hohensee: judge

- Hans-Georg Kluge: lawyer and university lecturer

About 86% of respondents to our culture survey agreed that ASF’s board supports the organization in achieving its strategic vision.

We believe that boards whose members represent occupational and viewpoint diversity are likely most useful to a charity, since they can offer a wide range of perspectives and skills. There is some evidence suggesting that nonprofit board diversity is positively associated with better fundraising and social performance53 and better internal and external governance practices,54 as well as with the use of inclusive governance practices that allow the board to incorporate community perspectives into their strategic decision-making.55 ASF’s board potentially lacks a diversity of occupational backgrounds and experiences. We consider the board’s relative lack of occupational diversity to be a weakness.

Policies and Benefits

Here we present a list of policies that, if properly drafted and enforced, we find to be beneficial for fostering a healthy culture. A green mark indicates that ASF has such a policy and a red mark indicates that they do not. A yellow mark indicates that the organization has a partial policy, an informal or unwritten policy, or a policy that is not fully or consistently implemented. We do not expect a given charity to have all of the following policies, but we believe that, generally, having more of them is better than having fewer.

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics/conduct | |

| Paid time off In Germany: 26 paid days off (legal minimum is 20 days) In Poland: 26 paid days off (legal minimum is 26 days) |

|

| Sick days and personal leave No limit on sick days (in accordance with German law) |

|

| Full healthcare coverage Health care plans are mandatory under German law, and reimbursement covers most health care costs and all salaries. Health care plans are also mandatory under Polish law. Reimbursement covers most health care costs and all salaries. |

n/a |

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| Regular performance evaluations | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| A formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) |

| A written statement that they do not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels of the managerial chain up to and including the Board of Directors56 | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| A practice documenting all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case57 | |

| Regular trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

| Flexible work hours | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for submitting reasonable accommodation requests | |

| Remote work option |

| Audited financial documents (including the most recently filed IRS form 990, for U.S. organizations) available on the charity’s website or GuideStar | |

| Board meeting notes available on the charity’s website | |

| List of board members available on the charity’s website | |

| List of key staff members available on the charity’s website |

| Formal orientation provided to all new employees | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Funding provided for books or other educational materials related to each employee’s work | |

| Paid trainings available on topics such as: diversity, leadership, and conflict resolution | |

| Paid trainings in intercultural competence (for multinational organizations only) | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support |

| The “€100 rule,” which allows all employees to buy/order anything that helps them with their work for up to €100—no questions asked |

Culture and Morale

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly toward all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. According to ASF’s leadership, a culture workshop they developed suggests that ASF has clear structures, rules, and processes; a sense of duty and community; a positive and respectful atmosphere; and a pragmatic and results-oriented side.

The survey we distributed to ASF’s staff supports leadership’s claim that ASF’s culture is overall positive. Respondents noted in an open-response box that they are happy to work at ASF and that they have a good team. Others noted that there is a high workload. A few common adjectives that respondents used to describe ASF’s communication style were “open,” “constructive,” “warm,” “friendly,” or similar.

According to our culture survey, ASF has an overall level of employee engagement close to the average of charities under review.

ASF has a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. Of the staff that responded to our survey, about 95% agreed with the statement that their compensation is adequate, highlighting their support for the new compensation model. ASF offers 26 paid days off to their employees, as well as unlimited sick days (according to German law). All respondents agreed that these paid benefits are sufficient. ASF reports that employees have clearly defined essential functions for all positions and that they regularly evaluate performance. About 26% of respondents in our culture survey agreed that the system of staff performance evaluation needs to be changed or improved upon.

ASF distributes regular culture surveys to their staff, in which they have identified two areas for improvement: feedback and recognition. ASF reports that they are taking steps to improve this by adding semi-annual feedback meetings and workshops for their leadership team.

Overall, we think that ASF’s staff satisfaction and morale are higher than the average charity we evaluated this year.

Representation/Diversity,58 Equity, and Inclusion59

One important part of acting responsibly toward stakeholders is providing a representative/diverse,60 equitable, and inclusive work environment. Charities that have a healthy attitude toward representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI) seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds. Among other things, inclusive work environments should also provide necessary resources for employees with disabilities, protect all team members from harassment and discrimination, and require regular trainings on topics such as equity and inclusion, in conjunction with year-round efforts to address R/DEI throughout all areas of the organization.

Among the staff that participated in our culture survey, 20% agree that ASF has members from diverse backgrounds, although some respondents noted that ASF is working to improve this. ASF’s leadership claims that creating a diverse team in Germany and Poland is harder than in the U.S., especially when it comes to race, as local animal advocacy movements mostly consist of white people. ASF reports that they made an effort to increase representation/diversity through their recruitment process by increasing female representation in their leadership team and by including an R/DEI statement in their job listings.

In our culture survey, some respondents mentioned that leadership could hire more diverse staff, improve board diversity, provide more training sessions, and move to a barrier-free office to be more inclusive or to better support staff who are members of marginalized groups.

ASF supports R/DEI through their human resource activities. ASF has a workplace code of ethics/conduct and a written statement that they do not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics. ASF has a written procedure for filing complaints and explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment61 or discrimination.62 In our culture survey, 95% of respondents agree that ASF protects staff, interns, and volunteers from harassment and discrimination in the workplace, and all agree that they have someone to go to in case of harassment or other problems at work. However, our culture survey suggests that ASF’s staff experienced or witnessed more harassment or discrimination in the workplace during the past year than the average charity under review. Because staff feel overall protected from harassment and discrimination, and ASF seems to have systems in place to prevent and handle harrassment and discrimination in the workplace, we are not highly concerned about this finding.

ASF offers regular trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace. In our culture survey, 76% of respondents agree that they and their colleagues have been sufficiently trained in matters of R/DEI. Some respondents mentioned that they received training only on sexual harassment. We believe that the opportunities for the team to learn about R/DEI at ASF should be increased.

Overall, we believe that ASF is less diverse, equitable, and inclusive than the average charity we evaluated this year.

Criterion 6: Strategy

Criterion 6

Strategy

Charities with a clear and well-developed strategy are more likely to be successful at setting and achieving their goals. In this section, we describe and assess each charity’s strategic vision and mission, plan, and planning process.

Given our commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we assess the extent to which the charity’s strategic vision is aligned with this commitment. We believe that their strategic planning should clearly connect the charity’s overall vision to their more immediate goals. Additionally, we assess the extent to which their strategic planning process incorporates the views of all their staff and board members and whether the frequency of this process is adequate, given the nature of their work. There are many different approaches to strategic planning, and often an approach that is well suited for one organization may not work well for others. Thus, in this section, we are not looking for a particular approach to strategy. Instead, we assess how well the organization’s approach to strategy works in their context.

Strategic Vision

ASF’s vision: “We advocate the abolition of factory farming and a widespread adoption of the vegan lifestyle. In doing so, we deliberately take intermediate steps by continuously raising animal welfare standards and reducing the consumption of animal products.”

Strategic Position in the Movement

We asked ASF how they see their organization’s work fit into the overall animal advocacy movement. They report that they aim to focus on programs that are relatively neglected in the countries they work in. For instance, in Germany, ASF say they observed that most other organizations focus on political lobbying. For this reason, they choose to focus on corporate outreach, corporate campaigns, legal work, and capacity building. They also consider cooperation with other organizations to be a central strategy of their organization.

Strategic Plan and Planning Process

Type(s) of plan: Three-year strategic plans

Leadership staff’s role: The President creates the first version of the strategic plan with a focus on impact. After receiving feedback from the board and other leadership staff, the President revises the plan. After receiving feedback from non-leadership staff, the President seeks feedback again from the board and leadership and finalizes the strategic plan. Other leadership staff gives feedback on the first and second versions of the strategic plan.

Board of directors’ role: The board gives feedback on the first and second versions of the strategic plan.

Non-leadership staff’s role: Non-leadership staff can give feedback on the second version of the strategic plan.

Contents of plan: ASF’s strategic plan includes high-level strategy to analyze how their program work contributes to achieving their mission/vision. As part of this analysis, their plan features an outline of the problem they are working to address, a theory of change, and a discussion of the strategy behind future initiatives. Additionally, they address their internal structure—e.g., culture—in their plan.

Goal Setting and Monitoring

ASF’s goals are set and monitored quarterly by the CEO, in discussion with the other leadership. ASF holds retrospective meetings—i.e., postmortems—following major projects. Key topics at these meetings include what went well, what to improve in the future, and lessons learned. Additionally, ASF develops annual reports on effectiveness, which they consider to be a form of self-assessment.

Our Assessment

We support ASF’s choice to focus on farmed animal welfare because we consider animal agriculture to be one of the most promising areas for doing the most good for animals, other things being equal. We think that they have a clear notion of how they fit into the wider animal advocacy movement and that this is reflected in their strategic decision to focus on interventions that are otherwise neglected in Germany. We think ASF engages in strategic planning at appropriate intervals, is clear on who makes final decisions, and ensures participation and periodic input from all levels of staff. Their strategic plan seems thorough, featuring high-level strategy that explains why each program is important and how they all interrelate, as well as future projections for the direction of each program, and considerations about their internal structure. That said, it doesn’t appear to cover their work in Poland, and we are uncertain how involved their Polish subsidiary is in the planning process. We think their goal setting seems quite top-down in its approach and could benefit from the contributions of non-leadership staff. We think they have a strong approach to self-assessment. Overall, we think ASF’s approach to strategy is strong compared to other evaluated charities, given the context in which they operate and the type of work they do.

Criterion 7: Adaptability

Criterion 7

Adaptability

A charity’s self-assessment should inform their decisions. This will aid them in retaining and strengthening successful programs and modifying or discontinuing less successful programs, and will enable them to see if or when it is necessary to change their organizational structures. When such systems of improvement work well, all stakeholders benefit: Leadership is able to refine their strategy, staff better understand the purpose of their work, and donors can be more confident in the impact of their donations.

We have identified the following examples of how ASF has adapted to success and failure:

When writing their yearly strategic plan, ASF reports that they try to identify the work that is most needed in the movement and adapt their programs accordingly.63 They assessed their corporate outreach program (launched in 2008) as successful and chose to expand it, leading them to divide the leadership of the program across two managers, instead of one. They also recently hired two new staff to work on corporate outreach. ASF reports that they launched a corporate campaign program in 2018 after observing that other organizations were successful and that there was no organization running corporate campaigns for farmed animals in Germany.

ASF also reports that they recently changed their fundraising program.64 They identified lead generation as one of their weaknesses, so they hired two external consultants who specialize in fundraising and lead generation. Whether this will improve the program is yet to be seen—they re-launched these activities in autumn of 2020.

Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected ASF’s ability to carry out some of their programs—they have paused their corporate campaigns and their offline consumer outreach.65 They report that they changed the focus of their corporate outreach, re-orienting toward sectors that are less affected by the pandemic. They also started to discuss pandemic risks and antibiotic resistance in articles on their website, when interacting with the media, and in their corporate outreach. ASF reported on how they are affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in a piece posted on ACE’s blog.

Overall, we believe that ASF is just as able as the average charity evaluated this year to respond adequately to success and failure.

Note that we are never 100% confident in the effectiveness of a particular charity or intervention, so three gray circles do not necessarily imply that we are as confident as we could possibly be.

We acknowledge that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has impacted each charity’s programs in various ways. This impact is addressed in Criterion 3: Cost Effectiveness.

We consider an intervention to be weakly effective if we believe it is unlikely to have a positive impact on the relevant outcome. We consider an intervention to be moderately effective if we believe it has some positive impact on the relevant outcome, though relatively less than other interventions. We consider an intervention to be highly effective if we believe it has a clear positive impact on the relevant outcome.

For arguments supporting the view that the most important consideration of our present actions should be their impact in the long term, see Greaves & MacAskill (2019) and Beckstead (2019).

M. Klosterhalfen reported in a personal communication on November 9, 2020 that ASF will no longer be conducting animal advocacy research from 2021 onwards.

M. Klosterhalfen reported in a personal communication on November 9, 2020 that from 2021 onwards, ASF will shift their focus to corporate outreach and campaigns training within the Open Wing Alliance.

ASF was founded in 2000. We show data for the last five years.

For further details, see our 2017 Giving Metrics Report, 2018 Giving Metrics Report, and 2019 Giving Metrics Report. At the time of writing this review, our 2020 Giving Metrics Report is not yet published.

We do not list any expansions beyond what the charity itself plans to implement. We acknowledge that charities may differ in how ambitious their reported plans are independent of what they can realize. Such a difference in reporting could bias our estimates of the room for more funding. To counteract such a bias, we first ask all charities not only for the expansions they already planned for 2021, but also which expansions they would plan if their budget would increase by 50%—they report these responses in Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2020a). Second, we indicate our confidence in whether the charities’ expansion plans could actually be realized. We refer to our evaluation of the effectiveness of ASF’s programs for an assessment of the effectiveness of their planned expansions.

For staff expenditure and any non-staff expenditure that is scalable with staff, we estimate confidence levels based on our researchers’ joint assessment of how feasible it is to hire a certain number of staff dependent on the organization’s current size.

For estimating the salary of a given role, we used the following sources of information in order of priority: current and past job postings by that charity, current and past job postings by similar charities, seniority and type of job, and average wages in the country of hire.

Note that our cost estimates for non-staff expansions account for the partial correlation between costs for new staff and non-staff costs that involve staff.

The column shows 90% confidence intervals assuming normal distributions for all variables, except for potential additional expenditure, for which we assume a log-normal distribution.

For staff expenditure and any non-staff expenditure that is scalable with staff, we indicate the proportion of the charity’s expansion plans that we are highly confident they’ll be able to achieve, the proportion we are moderately confident they’ll be able to achieve, and the proportion we have low confidence in. We generally have high confidence that reserves can be replenished if funds are available, and low confidence in the amount of unexpected expenditures the charity may have.

This is an estimate to account for additional expenditures beyond what has been specifically outlined in this model. This parameter reflects our uncertainty as to whether the model is comprehensive and constitutes a range from 1%–20% of the charity’s total projected 2020 expenditures.

We assume a linear trend in revenue. The estimates are based on a linear regression using ASF’s revenue data from 2015 to 2020.

M. Klosterhalfen reported on October 26, 2020 that retailers who join the AWI sign a Letter of Intent committing to “drive change in the aquaculture industry in order to enhance welfare standards internationally.”

ASF convinced a third retailer (Tesco) to also stop selling live carps in stores. Although Tesco published a policy committing to not sell live carps in their stores, they later leased commercial space in some of their locations to independent sellers of live carps, in effect circumventing the commitment.

Auchan had already banned the sale of live carps in 90% of their supermarkets in 2018, so this result refers to convincing Auchan to ban the sale of live carps in the remaining 10% of their supermarkets in 2019. Similarly, Selgros had already banned the sale of live carps in 33% of their stores in 2018, so this result refers to convincing Selgros to ban the sale of live carps in the remaining 67% of stores in 2019.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

M. Klosterhalfen reported in a personal communication on November 5, 2020 that some of the results of this program contribute to increasing the availability of animal-free products, while other results contribute to improving welfare standards. Klosterhalfen reported that 70% of the expenses of this program go toward improving welfare standards for farmed animals, and 30% of the expenses of this program go toward increasing the availability of animal-free products.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

We provide these estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. For more information, see this explainer page on subjective confidence intervals.

For more information, see Šimčikas (2019a) and Open Philanthropy (2019).

One of their board members was also involved in the successful court case against chick culling in Germany, but we do not consider this a direct success of ASF.

Guides were 91 pages in length and either physically taken at events (345) or downloaded from ASF’s website (244).

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

M. Klosterhalfen reported in a personal communication on November 5, 2020 that some of the results of this program contribute to increasing the availability of animal-free products, while other results contribute to improving welfare standards. Klosterhalfen reported that 70% of the expenses of this program go toward improving welfare standards for farmed animals, and 30% of the expenses of this program go toward increasing the availability of animal-free products.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

For more recent achievements (2019–2020), see Criterion 3: Cost Effectiveness.

For more recent achievements (2019–2020), see Criterion 3: Cost Effectiveness.

While we are able to verify some types of claims (e.g., those about public events that appear in the news), others are harder to corroborate. For instance, it is often difficult for us to verify whether a charity worked behind the scenes to obtain a corporate commitment or the extent to which that charity was responsible for obtaining the commitment.

Albert Schweitzer Foundation (n.d.-c); Albert Schweitzer Foundation (n.d.-e)

Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2018b); Marriott International (2018)

We recommend that charities refrain from taking a leading role in the countries they expand to and instead take on a more supportive role of the local movement, e.g., by sharing skills and providing funding to local groups.

We distributed our culture survey to ASF’s 37 team members and 21 responded, yielding a response rate of 56%. This response rate was particularly low, which reduces our confidence in our assessment of ASF’s organizational culture.

We recognize at least two major limitations of our culture survey. First, because participation was not mandatory, the results could be affected by selection bias. Second, because respondents knew that their answers could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer, they may have felt an incentive to emphasize their employers’ strengths and minimize their weaknesses.

M. Klosterhalfen, personal communication (November 9, 2020); Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2020d)

ASF reports that this policy is implemented when compliant with German laws, i.e., when there is consent from the victim.

ASF reports that this policy is implemented when compliant with German laws, i.e., when there is consent from the victim.

ACE uses the term “representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI)” in place of the more commonly used “diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).” While we acknowledge that the terms “diversity” and “DEI” are in the public lexicon, as the concepts have become popularized, “diversity” has lost the impact of its original meaning. The term is often conflated with “cosmetic diversity,” or diversity for the sake of public appearances. We believe that “representation” better expresses the commitment to accurately reflect—or represent—society’s demographics at large.

Our goal in this section is to evaluate whether each charity has a healthy attitude toward representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion. We do not directly evaluate the demographic characteristics of their employees.

We use the terms “representation” and “diversity” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of certain social identity characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries), such as race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, or genetic information.

In the culture survey we included the following definition of harassment: “Harassment can be non-sexual or sexual in nature. Non-sexual harassment refers to unwelcome conduct—including physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors—that upsets, demeans, humiliates, intimidates, or threatens an individual or group. Harassment may occur in one incident or many. Sexual harassment is defined as unwelcome sexual advances; requests for sexual favors; and other physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors of a sexual nature when (i) submission to such conduct is made explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment; (ii) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting the targeted individual; or (iii) such conduct has the purpose or effect of interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.”

In the culture survey we included the following definition of discrimination: “Discrimination is the differential treatment of or hostility toward an individual on the basis of certain characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries), such as race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, age, ability, genetic information, or any other factor that is legislatively protected in the country in which the individual works. ACE extends its definition of discrimination to include the differential treatment of or hostility toward anyone based on any characteristics outside of one’s professional qualifications—such as socioeconomic status, body size, dietary preferences, political views or affiliation, or other belief- or identity-based expression.”