Animal Advocacy in Brazil

- Introduction

- Animal Agriculture in Brazil

- Current State of the Animal Advocacy Movement

- Opportunities for Effective Animal Advocacy in Brazil

- Challenges to Effective Animal Advocacy in Brazil

- Conclusion

- Questions for Further Consideration

- References

We’d like to thank Sandra Lopes, Gustavo Guadagnini, Patrycia Sato, Guilherme Carvalho, Vivian Mocellin, and Lucas Alvarenga for participating as interviewees for this report. We’d also like to thank Carolina Macedo Galvani for providing us with external feedback.

Introduction

Brazil, Russia, India, and China (collectively known as the BRIC countries) are among those that kill the most animals for food.1 Economic development and the emergence of the middle class in these nations seems to be resulting not only in growing demand for meat and other animal products domestically, but also in the BRIC countries becoming leading exporters of animal products globally.2

To our knowledge, animal advocates have been active in Brazil for about 20 years,3 but it is only much more recently that they have turned their attention to farmed animals.4 With over 1.6 billion farmed land animals kept in Brazil in 2016, these animals account for the vast majority of human-caused suffering endured by animals in Brazil, and yet they are under-represented in advocacy efforts. Due to the vast number of animals farmed for food and other products in Brazil, the potential impact of advocacy on their behalf is significant. For this reason, this report focuses solely on advocacy for farmed animals.

Prior to this research, our understanding of animal advocacy in Brazil was relatively limited—this report intends to outline the main opportunities and challenges it faces. We conclude that there are numerous opportunities for the animal advocacy movement to help animals in Brazil, including (i) creating and expanding programs aimed at helping people to reduce their animal product consumption, (ii) expanding the plant-based alternatives market, (iii) increasing public awareness of farmed animal suffering through undercover investigations and protests, and (iv) using social media to spread advocacy messages. Compared to these opportunities, we think the movement is likely to face more barriers when advocating for welfare reforms and legislative change. Cultural considerations are important for all of these advocacy strategies—specifically, diversity and inclusion need to be considered in messaging in order to be relevant to Brazil’s diverse population.5

Methods

We conducted a literature search to find information about animal advocacy in Brazil using Google, Google Scholar, and the Animal Charity Evaluators (ACE) research library. In addition, we spoke with staff members from established animal advocacy and dietary change organizations in Brazil to better understand their work and the progress they have made. We interviewed staff from Animal Equality, Fórum Animal, Humane Society International (HSI), The Good Food Institute (GFI), Mercy For Animals (MFA), and Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (SVB). These organizations were selected based on a systematic search for advocacy groups in Brazil and contacts that ACE already had from previous work. Every organization that we contacted for an interview responded and participated, and all of the staff that we interviewed were located in Brazil. Our selection process resulted in an inclusion of more international charities headquartered outside of Brazil than charities that originated in Brazil, so our interviewees’ perspectives may not be representative of all of the animal advocacy organizations doing work in Brazil.

Animal Agriculture in Brazil

History

The Brazilian population has been growing rapidly since the 1960s—it reached 209.2 million in 2018 and is projected to rise to 214.8 million by 2022.6 An extremely high percentage of Brazil’s population is now living in urban areas,7 a trend which has been associated with an increased demand for animal products.8

Rapid economic growth since 1965 has led to Brazil becoming a middle-income country reaching a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of $1,939.79 in 1980.9 Incomes have since continued to rise and by 2016, the GDP per capita reached $8,649.95.10 Before the 1970s, Brazil lacked food security–there were constant food supply crises, widespread rural poverty, and a lack of effective agricultural development policies.11 However, food is now secure in the majority of the country and most of the population has risen up out of severe poverty (Monteiro & Cannon, 2012). The inclusion of meat in the Brazilian diet rose by nearly 50% between 1974 and 2003 and is now reportedly seen by many as a food needed in the everyday diet, despite historically low consumption (Monteiro & Cannon, 2012; Ribeiro & Corção, 2013).

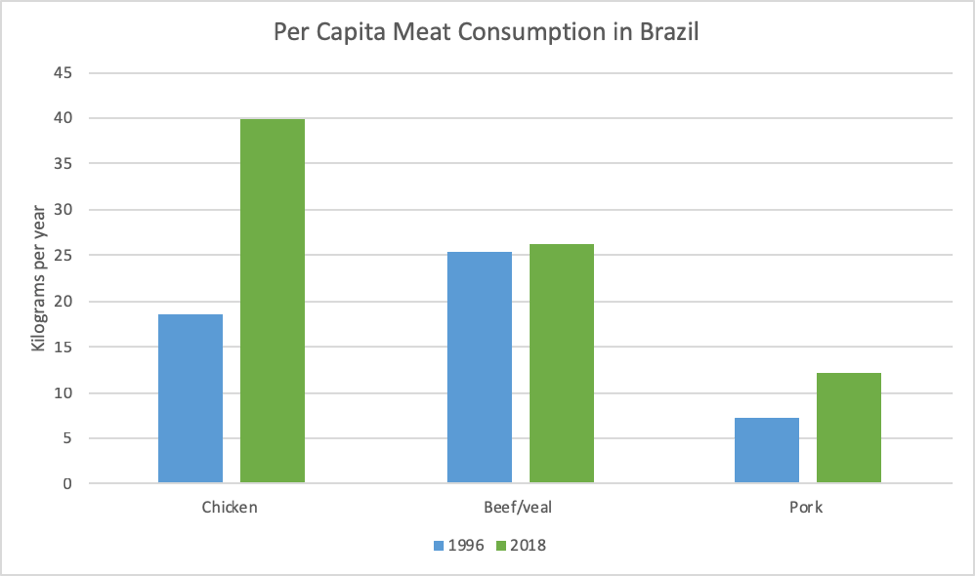

Figure 1. Data from Faunalytics (2018)

Milk, egg, and fish consumption have risen substantially since the early 1990s.12 The Brazilian diet now contains a very high proportion of land-based animal protein,13 and a higher proportion of fish depending on the region. In coastal areas and in the Amazon Basin, fish consumption is substantially higher than in inland areas–per capita consumption in the Amazon Basin can exceed 66lbs (30kg) per year.14 This compares to average Brazilian fish consumption of 42.3lbs (19.2kg) per capita in 2011–2013.15

Land Animals

Compared to the other BRIC countries, Brazil is the largest consumer per capita and exporter of beef and chicken.16, 17 Around 79% of food produced in Brazil is consumed domestically18 and the remaining 21% is shipped to over 180 foreign markets.19 Brazil is the world’s second largest exporter of meat products, and the largest exporter of chicken and bovine meat; it is also the second largest producer of bovine meat and the fourth largest producer of poultry20 and pig meat in the world.21

|

Bovine Meat Production: World Total and in Selected Countries (‘000 tonnes, Carcass weight equivalent) |

||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 (prelim.) | Change 2017 over 2016 (%) | |

| World | 68,667 | 69,728 | 70,779 | 1.5 |

| U.S. | 10,817 | 11,507 | 11,938 | 3.7 |

| Brazil | 9,425 | 9,284 | 9,553 | 2.9 |

| E.U. | 7,668 | 7,881 | 7,889 | 0.1 |

| China | 7,016 | 7,366 | 7,638 | 3.7 |

| Argentina | 2,727 | 2,644 | 2,824 | 6.8 |

| India | 2,518 | 2,522 | 2,553 | 1.2 |

| Australia | 2,662 | 2,361 | 2,387 | 1.1 |

Figure 2. Table from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2018)

|

Poultry Meat Production: World Total and in Selected Countries (‘000 tonnes, Carcass weight equivalent) |

||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 (prelim.) | Change 2017 over 2016 (%) | |

| World | 116,342 | 119,239 | 120,516 | 1.1 |

| U.S. | 21,017 | 21,483 | 21,998 | 2.4 |

| China | 17,895 | 18,710 | 17,665 | -5.6 |

| E.U. | 13,925 | 14,514 | 14,630 | 0.8 |

| Brazil | 13,636 | 13,391 | 13,645 | 1.9 |

| Russian Fed. | 4,088 | 4,141 | 4,440 | 7.2 |

| India | 3,292 | 3,426 | 3,591 | 4.8 |

| Mexico | 3,002 | 3,116 | 3,234 | 3.8 |

| Japan | 2,132 | 2,345 | 2,359 | 0.6 |

Figure 3. Table from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2018)

|

Pigmeat Production: World Total and in Selected Countries (‘000 tonnes, Carcass weight equivalent) |

||||

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 (prelim.) | Change 2017 over 2016 (%) | |

| World | 118,504 | 117,813 | 118,676 | 0.7 |

| China | 55,835 | 53,931 | 54,335 | 0.7 |

| E.U. | 23,467 | 23,618 | 23,429 | -0.8 |

| U.S. | 11,121 | 11,320 | 11,610 | 2.6 |

| Brazil | 3,519 | 3,700 | 3,725 | 0.7 |

| Viet Nam | 3,492 | 3,665 | 3,720 | 1.5 |

| Russian Fed. | 3,099 | 3,368 | 3,473 | 3.1 |

Figure 4. Table from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2018)

Agriculture, particularly beef production, has become one of the most economically important activities in Brazil for generating wealth and employment (Millen et al., 2011). In 2017, 10.32% of the population was employed in the agricultural industry, compared to only 2% in the United States.22 Farm land availability, a large domestic market, and liberalization of trade barriers have allowed firms to achieve economies of scale that have made Brazil a major—and growing—source of meat production. Typically, bovine meat producers in Brazil are independent, operate on private land, and do not rely on debt financing; however, the Brazilian government does have a number of programs in place to assist with the cost of pasture improvement, the purchase of machinery, and the construction of warehouses and silos (Matthey et al., 2004; Millen et al., 2011). Confinement systems for bovine meat production are increasingly being used in place of pasture by producers who want to expand their operations but are unable to purchase more land. Intensive confinement systems are also increasingly being used as a way to avoid further deforestation.23

The percentage of beef exported from total production in Brazil has risen from 13.4% in 2002 to 28.2% in 2007 (Millen et al., 2011). Part of the reason for this was the introduction of the Brazilian System of Identification and Certification of Bovine and Buffalo (SISBOV) which launched in 2002 as a traceability scheme and allowed Brazil to gain access to export markets such the European Union.24 More recently, the Brazilian government has intensified trade missions and export promotion of beef to markets such as Russia, Asia, and the Middle East.25

Unlike bovine production, poultry26 and pig meat production are mainly organised through contractual agreements, especially for meat destined for export markets (Matthey et al., 2004). The government also provides investment assistance to the poultry and pig meat sector by providing funds for upgrading processing facilities and financing meat exports through the National Bank of Economic and Social Development.

| Number of Land Animals Produced/Slaughtered in 2016 | ||||

| Brazil | United States | World | Brazil as % of World | |

| Cattle27 | 37,595,000 | 31,188,800 | 302,018,862 | 12.45% |

| Chickens | 6,078,968,000 | 8,909,014,000 | 65,847,411,000 | 9.23% |

| Ducks | 5,299,000 | 27,268,000 | 3,056,103,000 | 0.17% |

| Goats | 2,724,484 | 577,500 | 45,986,100 | 0.59% |

| Pigs | 39,805,749 | 118,303,900 | 1,478,167,073 | 2.69% |

| Sheep | 5,702,555 | 2,332,600 | 551,420,651 | 1.03% |

| Turkeys | 90,551,000 | 243,255,000 | 673,278,000 | 13.45% |

| Dairy cows | 19,678,817 | 9,328,000 | 273,782,778 | 7.19% |

| Egg-laying hens | 319,656,000 | 365,336,000 | 7,671,156,000 | 4.17% |

| Total28 | 6,599,980,605 | 9,706,603,800 | 79,899,323,464 | 8.26% |

Figure 5. Data from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2018)

Fisheries and Aquaculture

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that 3.5 million people are involved in fishing and aquaculture in Brazil, either directly or indirectly. Small-scale fisheries contribute around 50%–60% of total fish production from capture fisheries.29, 30 Aquaculture in Brazil is increasing–its contribution to total fish production increased from 21% in 2000 to 44% in 2011.31 As demonstrated in Figure 6, Brazil produced approximately three times more farmed fishes32 than the United States in 2012.33 Given the large scale and relative neglectedness of farmed fish suffering34 in Brazil (and worldwide), we think that advocates should consider fish welfare of at least equal importance as land animal welfare in Brazil.

| Aquaculture in 2012 | |||

| Brazil (metric tons) | United States (metric tons) | Brazil as % of World | |

| Inland aquaculture | 611,343 | 185,598 | 1.6% |

| Marine aquaculture | 0 | 21,169 | 0% |

| Farmed fish total | 611,343 | 206,767 | 1.4% |

Figure 6. Data from Business Benchmark on Farm Animal Welfare (2016)

Corporations

For several decades, meat production chains in Brazil have been dominated by foreign-owned transnational corporations that were the country’s leading exporters. However, between 2007 and 2013, the Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social (BNDES) (Brazilian National Development Bank) instigated the National Champions Policy. This policy aimed to transform Brazilian exporting companies into large transnational corporations that would bring in high revenues to the country.35 These companies included JBS, Marfrig, and BRF, which received large volumes of resources through subsidized loans and the purchasing of company shares through BNDES’ investment arm, BNDESPar.36

JBS’s value rose rapidly from $1 billion in 2004 to $34 billion in 2014 as it expanded into the production of chicken meat and other sectors—it is now Brazil’s largest beef processor and the world’s largest exporter of meat, selling to over 150 countries.37 After JBS, the second largest beef processor in Brazil is Marfrig, which processes 3.8 million cows, 2.3 million sheep, and 250 million birds per year and owns Keystone, one of the largest international suppliers of fast food chains such as McDonald’s, Subway, and Wendy’s.38

The merger of Perdigão and Sadia in 2009, financed by BNDES, resulted in the formation of BRF and caused a significant increase in corporate concentration in the poultry39 processing sector—BRF is now the seventh largest food corporation in the world and the largest international exporter of chicken.40

The integration of Brazilian transnational corporations into the global meat market is leaving them susceptible to public pressure to improve animal welfare.41 Five of the major pig producers including BRF and JBS announced that they would end the ongoing use of sow gestation crates,42 which are banned in the European Union and eight U.S. states. It is, however, considered improbable that upgrading legal European animal welfare standards will have any significant impact on the global trade of poultry meat43 (Horne & Achterbosch, 2008).

Animal Welfare Laws

Basic legislation for animal protection has existed in Brazil since 1934.44, 45 In addition, the Brazilian constitution has a chapter for environmental protection and recognizes that animals have fundamental interests (Clayton, 2011). Although there is no formal recognition of animal sentience under Brazilian law, the constitution provides that the government must protect animals from all practices that subject them to cruelty.46 In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled that the ox festival (Farra de Boi)47 violated constitutional rule; this was a historic ruling as it recognized that animals have the right to legal protection against suffering and mistreatment (Clayton, 2011).

The Environmental Crimes Law was established in 1998 and gave the government the authority to deal with cruelty issues to any category of animal at federal, state, and municipal levels (Clayton, 2011). This law prohibits engaging in an act of abuse, mistreatment, injuring, or mutilating wild, domestic, or domesticated animals, including circumstances where cruelty is carried out as part of experimentation for educational or scientific purposes.48 In combination, the constitution, the 1934 legislation, and the 1998 legislation provide some basic protections for animals concerning abuse, cruelty, and neglect. However, the laws are not comprehensive and exemptions under the 1998 Environmental Crimes Law are potentially wide reaching, making enforcement difficult.

While there are recommended guidelines49 for best practice during the rearing, transport, and slaughter of farmed animals,50 under existing regulations, there are no mandatory standards of care for farm management practices (Cardoso, Keyserlingk, & Hötzel, 2017). The guidelines51 that regulate pre-slaughter handling and slaughter state that all handling should cause a minimum of excitement and discomfort. They also forbid the use of aggressive instruments and the causing of a reaction of distress.52

The Permanent Technical Commission on Animal Welfare53 was established in 2011 to coordinate the Ministry of Agriculture’s animal welfare work and to facilitate farmers’ adoption of best animal welfare practices.54 However, changes were made by the government in 2017, and now the main body which technically regulates animal welfare within the government is called the Coordination of Good Practices and Animal Welfare, though it reportedly has limited influence within the current government structure. The Secretariat of Agribusiness International Relations, a division of the Ministry of Agriculture, is responsible for working with the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE). Among other things, the OIE has put forth an Aquatic Animal Health Code in which it sets out standards for the improvement of farmed fish health and welfare worldwide.55

The Brazilian government has prioritized animal welfare during transport and slaughter and has made progress towards implementing the OIE standards, but more work needs to be done to implement these standards during the rearing of livestock.56 It seems like the stricter requirements of some export markets and the need to pass welfare checks57 has provided motivation for meat production companies to improve their facilities, equipment, and management (Costa, Huertas, Gallo, & Costa, 2012).

Although there are designated individual responsibilities relating to animal protection within the government, there is no primary strategy for improving animal welfare, nor is there an individual with overall responsibility for animal welfare across the country.58 Furthermore, Brazilian law still permits some of the most controversial factory farming practices such as sow stalls, farrowing crates, and battery cages.59

Current State of the Animal Advocacy Movement

A systematic search60 found 131 organizations and groups operating in Brazil that had some link to improving animal welfare. Many of these were Facebook groups or extremely small grassroots organizations. The vast majority had a focus on companion animals such as cats and dogs. A number of sanctuaries and rescue centers are also included in this estimated figure. Of these 131 organizations, only 18 had clear relevance to farmed animals. Of these 18, those that seem to be the largest and most established are: Animal Equality, Fórum Animal, The Good Food Institute (GFI), Humane Society International (HSI), Mercy For Animals (MFA), World Animal Protection, and Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (SVB). There is also Sinergia Animal, a much newer organization which was founded in October 2017. Three of the organizations are native to Brazil (Fórum Animal, Sinergia Animal, and SVB). The other five are international organizations operating in Brazil among other countries.

Reducing Consumption of Animal Products

A significant part of the movement in Brazil is focused on dietary change advocacy. An example of a very successful meat reduction project comes from HSI: They worked with school districts in four cities in the state of Bahia—Serrinha, Barrocas, Teofilandia, and Biritinga61—to implement a “Sustainable Schools” program which reduces the animal product content in school meals by 25% every six months. Launched in March 2018, they have already achieved a 50% reduction in the animal product content of school meals. The project will reportedly impact around 23 million meals each year. This achievement is particularly notable as it is reportedly the first time a commitment has been made in Brazil to switch to a 100% plant-based menu.62

The international “Meatless Monday” program has been supported in Brazil by HSI, MFA, and SVB, and it has had great success in its implementation. Launched in 2009 with the support of the São Paulo City government, the food policy was implemented two years later in public schools in São Paulo City.63, 64 It was then implemented at the state level in 2013 and is also being introduced into prisons.65 HSI, MFA, and SVB continue to collaborate to implement the program in government agencies, other cities, and other states. SVB has a strategic focus on São Paulo, but HSI and MFA also work in other locations across Brazil. In 2017, 47 million meat-free meals were served across the country as a result of the “Meatless Monday” program.66

In addition, MFA runs its own “Conscious Eating” program which aims to implement food policies to reduce meat, dairy, and egg consumption by 20% in public schools, cities, governments, and at the state level.67 Since it started last year, the program has been very successful with eight policy commitments received in Brazil by the end of 2017.68 With regards to options for animal product replacements, GFI has been working in Brazil since 2017 to facilitate the innovation and development of the plant-based alternatives market.

SVB runs a program called “Vegan Option” which is aimed at the food service sector and which encourages establishments to introduce a vegan option to their menus. They also have a vegan labeling program which is designed to help consumers identify products without animal-based ingredients and products that have not been tested on animals during the development or manufacturing process.69 VegFest, which is organized by SVB, is now held annually, alternating between São Paulo and other Brazilian cities each year. In 2018, the event had a record number of attendees at around 9,000 people. SVB believes it acts as a significant motivator for activists in the movement.70

Welfare Reforms

Advocates have also focused on welfare reforms to reduce farmed animal suffering. Work in this area is still very new to Brazil and so far, the main focus has been on phasing out battery cages and sow gestation crates. The organizations that are currently working on these issues are Animal Equality, Fórum Animal, HSI, MFA, and Sinergia Animal. With the exception of HSI, all of these organizations are members of the Open Wing Alliance, an international coalition of organizations working towards ending the use of battery cages.

Retailers and other companies may at times be unaware of the source of their eggs and believe that they come from cage-free production systems.71 Some advocacy organizations have been working to educate and persuade companies to commit to purchasing cage-free eggs—ideally, this will demonstrate the demand for cage-free eggs to producers. There has been a good deal of success achieved to date, with around 80 companies72 making commitments to switch to cage-free eggs, including Brazil’s largest retailer Carrefour. Producers are informed of the pressure on retailers and other companies to go cage-free but often express concerns that these systems will increase egg prices, possibly up to 30%.73 Many producers do not have experience producing eggs in systems without cages, so a significant part of the work being done by advocates is educational.

Investigations, Protests, and Lawsuits

Animal Equality and MFA have both carried out undercover investigations in Brazil.74 In 2017, Animal Equality captured footage at Yabuta, one of Brazil’s top egg suppliers, exposing the conditions that laying hens are typically kept in across the country.75, 76 The same year, MFA also released footage from an investigation of an egg producer in Brazil.77

A current issue that multiple organizations have been working on is that of live exports. In December 2017, the Santos Harbor was reopened for the shipment of live bull calves to Turkey for the first time in 20 years. As a result, Fórum Animal filed a national lawsuit on December 15, 2017 in order to ban live exports across Brazil.78 Activists blocked the port and protested at the Turkish embassy, at the Minerva Foods headquarters (the company that owned the animals), and in the center of São Paulo City.79 Advocates are still working to end live animal exports from Brazil.80

Opportunities for Effective Animal Advocacy in Brazil

Growing Demand for Plant-Based Products

Brazil’s population seems to be growing increasingly aware of a number of issues surrounding the food that they eat.81 Animal advocates have suggested that the scandals involving contaminated and rotting meat in 2017 may have helped their cause.82, 83 In March 2017, the main beef producing corporations in Brazil—JBS, BRF, Marfrig, and Minerva—were involved in a widely publicized food safety scandal84 in which they were accused of bribing food safety inspectors and health officials to allow the sale and export of contaminated and rotting meat products.85 These scandals allowed advocates greater opportunities for engagement with the media, while also making evident the ties between corruption, sanitation, and animal welfare.

There is evidence that Brazilians are already beginning to shift their diets away from animal products. For instance, GFI conducted research which suggested that 30% of Brazilians are reducing their consumption of meat and other animal products.86 Generally, vegetarianism and the consumption of plant-based products seems to be viewed in a positive way, with an estimated 70% of Brazilians perceiving a vegetarian diet to be a positive lifestyle choice.87 The vegetarian and vegan communities in Brazil are growing rapidly, with 14% of Brazilians self-declaring88 as vegetarian as of April 2018 in a poll conducted by SVB.89

Currently, processed plant-based products are considerably more expensive than animal-based products.90 This is partly because the ingredients used in the manufacturing of processed plant-based products, such as pea protein, are not produced in Brazil and are therefore imported, and partly because the market is still relatively small, which means companies are not yet able to benefit from economies of scale.91 GFI is working with a government research institute to develop ingredients made from raw materials available in Brazil, which will likely have a significant impact on the price of products.92 They are also working to develop the plant-based market by bringing together technology licensed for use in the U.S. and companies developing plant-based products in Brazil. The increasing demand for competitively priced, good quality, and widely available plant-based products presents a huge opportunity for the industry to grow.93

Personal health is a very important consideration for Brazilians. HSI reported that Brazilians are developing diseases associated with excessive consumption of animal-based products such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes at increasingly young ages, sometimes even in childhood. Obesity is a rapidly increasing health concern, particularly in children. Lactose intolerance is also becoming more common, increasing the demand for plant-based milks. HSI also said that the benefit to personal health is the most effective argument to persuade people to shift their diet away from animal products.94

The health market in Brazil has been growing around 20% each year, significantly more than the global average of 8%,95 indicating that health concerns may be a key factor that the animal advocacy movement can take advantage of. GFI reported that 50% of vegans in Brazil cited health as their main motivation to switch their diet—for reducetarians, this figure was 70%. GFI believes that this trend is of benefit to the growth of the plant-based products market, as brands that promote themselves as being health foods tend to grow very quickly.

Concern for Animal Welfare

Relatively little is known about the Brazilian population’s attitudes toward livestock production systems and animal welfare. On other issues, Brazilians are generally very receptive to animal welfare messages; for example, they’ve been receptive to messages concerning companion animals like cats and dogs.96 Successful advocacy on their behalf is relatively straightforward considering the fact that companion animals are often viewed as family members.97 While advocacy for farmed animals is bound to be more difficult, SVB believes that Brazilians’ concern for companion animals is beginning to translate into an awareness of farmed animal welfare.98

A study by Faunalytics suggested that of all the BRIC countries and the United States, Brazilians had the most pro-animal attitudes.99 This study’s results indicated that an estimated 45% of Brazilians believe that eating meat directly contributes to the suffering of animals, 89% believe it is important that animals used for meat should be well cared for, and 70% would support a law that requires animals raised for food to be treated more humanely.100 Yunes, Keyserlingk, and Hötzel (2017) reported that an estimated 79% of Brazilians surveyed believe farmed animals are treated poorly. Similarly, MFA ran a survey in Brazil which showed that 81% of participants were concerned with the way farmed animals used for food are treated.101

Ruby et al. (2016) conducted a study on college students from Brazil, Argentina, France and the United States exploring attitudes towards beef and vegetarianism. They reported that ambivalence towards beef was higher in women than men and, of the countries included, it was the highest in Brazil. Among their participants, positive attitudes towards beef were lowest among Brazilian women and negative attitudes towards beef were most common in American and Brazilian women.

A study by Cardoso et al. (2017) suggested that Brazilian citizens show a preference for “free-range,” “cage-free,” and “more natural” production systems when asked about their opinions on practices used to rear laying hens, beef cows, pregnant and lactating sows, and chickens. Yunes et al. (2017) reported that Brazilians justify these preferences based on animals’ freedom to move, naturalness, and ethics.

Yunes et al. (2017) reported low levels of awareness among Brazilian citizens regarding animal production systems and practices, and note that this type of knowledge has decreased in the general public, largely due to urbanization which places a greater physical distance between livestock and where the consumers live. Faunalytics (2018) reported that when asked about practices common to dairy farming, only 45% of Brazilians were aware of early cow-calf separation, 21% were aware that new born male calves are culled, and 15% knew about dehorning without pain control. Those that were aware learned about these practices from the internet, television, and to a lesser extent from animal protection sources. When these practices were described to those unfamiliar with them, they were overwhelmingly considered morally unacceptable.

However, there does appear to be some variation in awareness—most participants in the Yunes et al. (2017) study were aware that pigs and poultry are reared in confined and caged systems and that cows are reared on pasture. They were also able to express expectations and criticisms regarding the quality of life of livestock. In addition, Cardoso et al. (2017) reported that Brazilians change their perceptions regarding the consumption of meat after they are shown images of the mistreatment of farmed animals–once informed of production practices, they expressed concern for the animals’ welfare.

Further research into understanding Brazilian attitudes toward farmed animals is needed, but it appears there is significant potential to improve consumer awareness, which may have important impacts on consumer choices. We believe that undercover investigations and social media outreach are of great value in informing the general public about common animal agriculture practices. Social media content in particular already receives a very positive response from the Brazilian public, although Fórum Animal expressed concern about the potential danger of some activists sharing sensational but inaccurate information which, if exposed, could undermine the movement by creating general skepticism towards all information about the suffering of animals.102 Further research is needed to understand the most effective ways to engage the Brazilian public, both in person and online.103, 104

Corporate Engagement and Increasing Organization of the EAA Movement

Corporate engagement work has achieved a good level of success so far in Brazil. GFI reported that companies are particularly concerned about being held accountable for the environmental impact of animal agriculture. They explained that almost 92% of the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest is due to either expanding cattle pasture or soy farming, which is mainly used for animal feed. Beef production in Brazil is not as efficient as it is in the U.S.—in Brazil, the chosen breed of cow doesn’t grow as big, so less meat is produced even with a larger number of animals. As cows are raised on pasture, rather than in intensive systems, land use is a major problem. Food security will be at risk if consumption patterns do not change since there is not enough space to continue to feed the growing population.105

The environmental issues106 in Brazil are more urgent than in some other countries; the Brazilian Amazon is said to be a tipping element of the entire earth ecosystem.107 While an environmental approach is not likely to be useful for welfare reform efforts, it does add significant weight to the case for replacing animal-based products with plant-based ones. Retailers in particular have seemed receptive to change, perhaps because they want to keep up with the development of plant-based products in other parts of the world.108

Food companies—especially the largest producers—don’t seem to be concerned about animal welfare, but they may be motivated to sustain a positive public image when faced with criticism from animal advocates. Companies have faced negative publicity and financial losses as the EAA movement has become increasingly organized and has engaged in actions such as undercover investigations and protests against live exports.109 MFA noted that collaboration between advocacy organizations and companies will be essential in Brazil due to the specific manner in which business is conducted locally.110 They aim to build relationships with companies, but they have also used pressure tactics in campaigns including social media outreach, volunteer mobilization, and engagement with the media. Fórum Animal believes that large-scale public campaigns have been a catalyst of the existing welfare reform commitments in Brazil, especially because undercover investigations are new in the region and companies know that the public will find the practices that the footage shows to be morally unacceptable. When companies are concerned that their image is being undermined, they may be much more inclined to make welfare commitments.111

Animal advocacy in Brazil has until very recently been a grassroots movement, without professional or consolidated organizations.112 There has been a boom in international animal advocacy organizations setting up in Brazil in the past few years, although there are still only a few Brazilian organizations that operate as professional nonprofits.113 There is great potential for more Brazilian animal advocacy organizations to set up, particularly ones that focus on farmed animals. Sinergia Animal is an example of a young organization that has already achieved some notable accomplishments.

Potential to Work on Larger Scale Issues and in a Wider Geographical Area

MFA suggested the success that has been achieved with “cage-free” campaigns is the first step towards working on higher-impact welfare reform work. Other welfare reforms are likely to be more difficult to achieve, but the potential impact on reducing overall suffering is substantial due to the vast number of animals farmed in Brazil. Current priority areas of welfare reform are sow gestation crates114 and broiler chickens.115 To date, the movement has secured four commitments from large pork producers to end the use of sow gestation crates.116 MFA has also undertaken investigations into pig farming which generated considerable media attention.117

In addition, MFA believes that groups need to begin working on improving broiler chicken welfare as more than six billion are slaughtered each year in Brazil.118 At the time of writing, MFA is also investigating the potential for advocacy work on behalf of fishes, but this depends largely on whether the issue is considered important enough by the Brazilian population. In addition, Fórum Animal reported that there are no advocacy groups currently working on welfare improvements for dairy or beef cows.119 Work in this area is likely to be challenging due to the geographical scale and economic power of the industry, but it also has the potential to be high impact due to the number of cows farmed in Brazil.

The advocacy movement has been very careful to ensure they are aware of the work being done by other organizations in order to reduce the chances of overlapping. Organizations in Brazil have also made great effort to stay in constant dialogue and work collaboratively. SVB has prioritized advocating in São Paulo State for strategic reasons as it makes up around 20% of the country’s population, while HSI and MFA also work in surrounding areas.120 However, there are still large areas of Brazil that are not being covered by any organization. With a total population of over 200 million, there are many opportunities to engage with people in other regions. One promising tactic that is not yet being done involves engaging young people about the health benefits of plant-based diets. This is something that HSI expressed interest in doing, but they presently do not have the necessary funds or staff.121 In terms of geographical expansion, the successes achieved by HSI in Bahia and by SVB in São Paulo could translate to other states, and the increasingly available plant-based alternatives in larger cities could be made more accessible in other parts of Brazil.122

Challenges to Effective Animal Advocacy in Brazil

Political Influence, Corruption, and Personal Safety Concerns

One of the most significant challenges facing the EAA movement in Brazil is the relationship between agricultural producers and politicians.123 With animal agriculture contributing to a very large proportion of the GDP in Brazil, advocates face powerful opposition by those who have business interests in the industry.124 Advocating on behalf of agribusiness has powerful political influence in Brazil—over a third of the lower house and a quarter of the Senate seats are occupied by the Parliamentary Agricultural and Livestock Front (FPA), a caucus representing the interests of animal agriculture.125 Any attempts at legislative change will have to get past the FPA.126

In addition, many politicians are also producers and own vast quantities of land and capital. For example, the current Minister for Agriculture, Blairo Maggi, is a soybean farmer.127 Farmers who raise cows for beef are generally the most politically powerful and influential. Much of the funding for political parties in Brazil is provided by companies in the agriculture industry.128 This situation poses significant challenges for the EAA movement, in particular regarding legislative work.

Existing animal welfare laws are generally not respected, but if too much attention is drawn to this fact, there is a significant risk that the law would be changed to favor the producers due to their extensive political influence.129 There is also a risk that “ag-gag” laws could be introduced, as has happened in parts of the United States. Despite this, Animal Equality told us they believe there is potential to legally advocate on behalf of animals, and have already started developing relationships with judges and public attorneys to encourage them to reconsider how animals are viewed under Brazilian law.130

Despite Brazil having some of the toughest anti-corruption laws in the world, corruption remains endemic especially among elected officials who are often influenced by private or criminal interests, undermining their ability to make and implement policy.131 The legal anti-corruption framework in Brazil is strong—consisting of the Clean Companies Act, the Penal Code, and specific anti-corruption federal laws—but its enforcement is inconsistent.132

Corruption may be especially likely in the natural resource sector and at local levels of the judiciary as local political and economic interests have a strong influence, and Brazilian judges are reportedly susceptible to bribery.133 The judiciary is independent but also overburdened, inefficient, and often subject to outside influences, especially in rural areas.134 Protection for whistleblowers is minimal, going little beyond standard witness protection in criminal cases.135

Personal safety is also a concern for activists. Some parts of the country are perceived to be too dangerous for animal advocates to work in, due to the influence of large powerful producers.136 Agribusiness was named by the British NGO Global Witness to be the most dangerous industry for people who defend land against it, surpassing the mining industry for the first time.137 There is a significant possibility that activists entering farms in remote areas of Brazil will simply disappear.138 Animal Equality told us that there are certain areas in the north of Brazil that they avoid for undercover investigations due to the risk of violence.139

Difficulties Engaging with the Media

Media coverage140 of animal welfare issues and dietary change work in Brazil is extremely limited. HSI contacted over 300 media outlets regarding their work with school districts in Bahia but received no interest in reporting the story.141 As such, they had no national media coverage at all. MFA was also disappointed that their first investigation into laying hens received no media coverage.142 Their second investigation received some media attention, but the work was not portrayed in the manner they would have liked.

Willingness to report on animal welfare issues and dietary change is minimal, potentially due to the importance of animal agriculture to the Brazilian economy. In addition, much of the media is funded by the animal agriculture industry.143 Generally, interest in reporting such stories is only expressed when a large company or prominent politician is involved, or when there are significant economic implications.144 For example, to many advocates’ surprise, the issue of Minerva’s live exports received widespread coverage.145 Animal Equality told us they believe this was due to the widespread mobilization across a number of different groups in the movement, the filing of lawsuits, and the protests outside the courts.146 The meat industry scandals of 2017 also allowed for more attention to be drawn to issues of animal welfare and dietary change.147

MFA believes there is potential to use the momentum of existing coverage to draw attention to more impactful issues, such as broiler chickens and egg-laying hens.148 GFI is also working to encourage the media to change the way they approach the subject.149 However, gaining consistent attention from the media continues to present challenges—in 2018, the media was dominated by stories regarding the Presidential election, leaving little room for other topics.

Strong Meat Consumption Culture and Income Inequality

Meat is associated with financial wealth, strength, and fuel for working in Brazilian culture. Although this is true in many parts of the world, the status of eating meat is especially important to Brazilians. Gustavo Guadagnini, Managing Director at GFI in Brazil, stated that “[t]he most traditional dishes in the country are heavily packed with meat. Feijoada, a national dish eaten on Saturdays, is made with pork as well as beef and different types of sausages. On top of that, buying meat is seen as a sign of status and is related to the idea of masculinity, which is built into society.”150

In 2012, daily meat consumption in São Paulo was reported at 4.9oz (138g) per day for men and 2.9oz (81g) per day for women; this is now higher than the U.S. where average consumption in 2012 was 4.1oz (116g) and 2.5oz (71g) per day for men and women respectively (Carvalho, César, Fisberg, & Marchion, 2012). Beef is a particularly important meat for Brazilians (Ribeiro & Corção, 2013). Ruby et al. (2016) reported that the word most associated with beef among Brazilians was “barbecue,” suggesting a strong social aspect to the consumption of beef. These strong cultural associations can cause resistance to change and can pose problems in implementing new food policies such as “Meatless Mondays”.151

In addition, income inequality is still a major problem in Brazil. Animal-based products are relatively inexpensive in Brazil, whereas plant-based alternatives often cost three or four times as much.152 Veganism is still generally perceived as elitist in Brazil.153 For people on very low incomes, it is simply not possible to be as selective about the type or quality of the food that they purchase.154 For a Brazilian wanting to maintain social traditions such as barbecuing, vegetarian and vegan alternatives are unaffordable and inaccessible due to their high prices and relatively limited distribution. The market is growing, and plant-based options can be found in the largest cities such as São Paulo, but even in Rio de Janeiro it can be difficult to find alternatives in restaurants and supermarkets.155

Immaturity of the Movement, Cultural Considerations, and Fundraising Difficulties

Nonprofit organizations are a relatively new concept in Brazil.156 HSI told us they have some difficulty explaining to decision-makers that the services HSI offers, such as culinary training, are free of charge. This is particularly relevant to organizations that work on meat reduction and animal advocacy as the movement itself is so new.

Animal Equality told us that adapting their overall international strategy to the specific conditions in Brazil is a challenge, and noted that tactics that work well in other countries do not necessarily translate successfully to Brazil.157 Vivian Mocellin, Executive Director of Animal Equality in Brazil told us the following:

“I think part of the reason veganism is viewed as elitist here is that people see digital influencers on social media platforms, especially Instagram, and they don’t feel represented as most of the mainstream vegan influencers are white, wealthy, young, slim, and living in big cities. In a multicultural country with huge income inequality such as Brazil it is very important to be representative of diversity if we want to be the most effective, reach the most people, and to have the biggest impact. It is worth noting, for example, that the gender-based movements and the Black movement are really strong and have a significant influence especially with millennials, which in turn tend to influence their families and surroundings, so if we can establish a dialogue with those movements to get veganism on their agendas, we can potentially reach many more people than we can alone. That’s why we have also been careful in terms of opening space and promoting to people from all ages, races, genders, sexual orientations, and also from different locations, including the big cities, the countryside, the suburbs, and the favelas to talk on our platforms, so that we are representing many different cultures and allowing everyone to think about veganism within their own realities. It deconstructs the idea that veganism is for few people. Creating content and communicating to people in Brazil can’t be about literally translating content from Europe or the U.S., as it requires the ‘tropicalization’ of strategies and content to make sense to local people, to speak to their own cultural identities and socioeconomic realities. That’s why we don’t promote lots of industrialized products on our platforms, because it is not accessible to most of people in the country, and because of the recurrent ethical concerns involving large food companies in the country, including human rights violations, which very frequently leads to backlash against the vegan movement when it promotes plant-based foods from these same companies. Instead we make our focus and priority to show people ways to make vegan food at home using ingredients that are cheap and accessible everywhere in the country.”158

Language translations have also posed a problem when trying to explain the work of advocacy organizations. For example, the term “cage-free” doesn’t translate well into Portuguese, which has resulted in using phrases that are less specific and have been less successful.159 Similarly, GFI said that the term “plant-based” also doesn’t translate well into Portuguese. When the media reports on plant-based products, a number of different terms are used and there is little understanding of which are the best-received by the public.160 Further research is needed to understand the best terms to describe animal product alternatives.

There is still little consensus across groups about which approaches, such as meat reduction or welfare reforms, are the most effective to reduce animal suffering.161 SVB suggested that although this issue is not exclusive to Brazil, when compared to the movement in the U.S., they believe the movement in Brazil is lagging behind in its understanding of the work of other organizations and the variety of different potential approaches. Animal Equality said that discussions between animal advocacy groups can be tense, but if these differences could be overcome, there is great potential for international and grassroots organizations to work together on issues that can make a real impact.162 Animal Equality also noted that it is important to have a dialogue with local activists who have been working in Brazil for years before the arrival of international advocacy organizations—these groups have a wealth of experience and knowledge which is extremely valuable to the movement.

For organizations that originated in Brazil, fundraising can be difficult as the Brazilian Real (BRL) is of much lower value than the U.S. dollar or the Euro. In addition, donations made to charities in Brazil are subject to Inheritance upon Death and Donation Tax (ITCMD). Each state is free to decide the rate at which it will charge ITCMD, but it typically ranges from 2% to 8%.163 Some states have full or partial tax exemptions for nonprofits.164 International organizations have the option of receiving funding from outside of Brazil—MFA, for example, receives around 98% of their funding from the United States.165 International organizations are able to set up in Brazil with a team of paid staff funded from foreign donations, while a new organization setting up locally would likely have to run on a volunteer basis, as SVB did for the first 10 years after it was founded.166 As a native Brazilian organization, without foreign funding at present, SVB has developed innovative fundraising methods including their Vegan Label program and annual VegFests.

Conclusion

We believe that effective animal advocates in Brazil have great potential to make significant progress on reducing farmed animal suffering across the country. Efforts to reduce animal product intake in Brazil seem especially promising considering the trends towards plant-based diets that are already developing, as well as relatively high levels of regard for animal welfare in Brazil compared to the U.S. and other BRIC countries. Development of more locally available, culturally accessible, and affordable plant-based alternatives seems likely to significantly increase the number of people who are able and willing to change their diets. In addition, collaboration with other social movements and inclusion of people from outside major cities seem likely to be effective strategies for increasing the accessibility of meat reduction messaging.

Research into Brazilians’ attitudes towards animal welfare suggests that it is possible to persuade the Brazilian public that farmed animals deserve moral consideration. Given the difficulties of engaging with the media, social media is a very promising opportunity to educate the public; advocates can use social media platforms both to share footage from undercover investigations, and to educate the public about what they can do to reduce suffering. More research is needed to understand which messages are best-received by Brazilians.

Achieving welfare reform is likely to be more difficult in Brazil than elsewhere due to the significant political influence of producers and the lack of understanding of alternative systems of production. Working to educate producers on systems that are better for animal welfare seems like a plausible next step. Legislative change will likely be challenging to achieve and requires very careful planning. However, advocates report a high level of goodwill towards welfare reform in Brazil and the more that change can be framed as good for business, the more receptive companies are likely to be. Groups that are mindful of the political, social, and economic context of Brazil have a number of opportunities to make substantial impact.

Questions for Further Consideration

- What types of farmed animal advocacy messages are best-received by the Brazilian public?

- What is the potential for legislative change to improve farmed animal welfare? What challenges are likely to be faced in achieving this?

- How likely is it that corporations will follow through on the commitments they have made so far? What potential barriers could they face?

- How can the movement engage more effectively with the media?

- How can the movement use education to further the cause? Is there potential to work with children?

- What is the risk of “ag-gag” laws being introduced?

- How can the movement better understand the needs and concerns of producers?

References

Clayton, L. A. (2011). Overview of Brazil’s Legal Structure for Animal Issues. Michigan State University, Animal Legal and Historical Center. Retrieved from: https://www.animallaw.info/article/overview-brazils-legal-structure-animal-issues

Cardoso, C., Keyserlingk, M. V., & Hötzel, M. (2017). Brazilian Citizens: Expectations Regarding Dairy Cattle Welfare and Awareness of Contentious Practices. Animals, 7(12), 89. doi:10.3390/ani7120089

Carvalho, A. M., César, C. L., Fisberg, R. M., & Marchioni, D. M. (2012). Excessive meat consumption in Brazil: Diet quality and environmental impacts. Public Health Nutrition, 16(10), 1893-1899. doi:10.1017/s1368980012003916

Costa, M. J., Huertas, S. M., Gallo, C., & Costa, O. A. (2012). Strategies to promote farm animal welfare in Latin America and their effects on carcass and meat quality traits. Meat Science, 92(3), 221–226. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.03.005

Horne, P. V., & Achterbosch, T. (2008). Animal welfare in poultry production systems: Impact of EU standards on world trade. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 64(01), 40–52. doi:10.1017/s0043933907001705

Matthey, H., Fabiosa, J.F., & Fuller, F.H. (2004). Brazil: The Future of Modern Agriculture? Iowa State University MATRIC Briefing Papers, 8. Retrieved from: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/matric_briefingpapers/8

Millen, D. D., Pacheco, R. D., Meyer, P. M., Rodrigues, P. H., & Arrigoni, M. D. (2011). Current outlook and future perspectives of beef production in Brazil. Animal Frontiers, 1(2), 46–52. doi:10.2527/af.2011-0017

Monteiro, C.A., & Cannon, G. (2012). The impact of transnational “Big Food” companies on the South: a view from Brazil. PLOS Medicine, 9(7), 1–5.

Ribeiro, C.D.G., & Corção, M. (2013). The consumption of meat in Brazil: between socio-cultural and nutritional values. Demetra, 8(3), 425–438.

Ruby, M. B., Alvarenga, M. S., Rozin, P., Kirby, T. A., Richer, E., & Rutsztein, G. (2016). Attitudes toward beef and vegetarians in Argentina, Brazil, France, and the USA. Appetite, 96, 546–554. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2015.10.018

Yunes, M., Keyserlingk, M. V., & Hötzel, M. (2017). Brazilian Citizens’ Opinions and Attitudes about Farm Animal Production Systems. Animals, 7(12), 75. doi:10.3390/ani7100075

See the 2018 Faunalytics report titled “Attitudes Toward Farmed Animals In The BRIC Countries” for more information.

See the 2018 data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations for information on production, exports, and more.

For example, a Brazilian documentary titled A Carne é Fraca was released in 2004. The film showed the harmful effects of meat production on animal welfare and on the Amazon rainforest.

For more information, see our Conversation with Patrycia Sato of Fórum Animal (2018).

The CIA World Factbook (retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/br.html) reports the following distribution of “ethnicities” among the Brazilian population: “white 47.7%, mulatto (mixed white and black) 43.1%, black 7.6%, Asian 1.1%, indigenous 0.4% (2010 est.)” based on census data from the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics). It’s important to note that the Brazilian census categories for race/ethnicity are not perfect: For example, research suggests the current categorization may lead to a misunderstanding of inequality in Brazil. See “The Consequences of “Race and Color” in Brazil” by Ellis P. Monk, Jr. for a discussion of these issues.

See the 2018 Faunalytics report titled “Attitudes Toward Farmed Animals In The BRIC Countries” for more information.

A 2018 Faunalytics report titled “What Do Brazilians Know About The Dairy Industry?” reported that 84% of Brazilians live in urban areas compared to a world average of 54% in 2017.

See the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) 2018 data on meat consumption for more information.

From indexmundi.com. The website uses data from the World Bank and OECD national accounts data files.

From indexmundi.com. The website uses data from the World Bank and OECD national accounts data files.

From OECD Conference on Agricultural Knowledge Systems 2011. This conference presentation notes that in 40 years, Brazil has developed to become one of the largest agricultural producers in the world and the largest economy in South America.

“Meat and Seafood Production & Consumption” (Our World in Data, 2017) shows that milk consumption has increased from 96.94 kg per capita in 1990 to 149.28 kg per capita in 2013; egg consumption has increased from 7.35 kg per capita in 1990 to 8.98 kg per capita in 2013; and fish consumption has almost doubled since the early 90s, with an average consumption of 5.8 kg per capita in 1990 rising to 10.87 kg per capita in 2013.

The Voiceless Animal Cruelty Index website states that the Brazilian diet contains 54% land-based animal protein compared to a global average of 35.2%.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations website states that there have been widespread advertising campaigns promoting the consumption of fish across Brazil, which have contributed to this increase in consumption.

See “Huge Increase Expected in Brazil’s Fish Consumption” (The Fish Site, 2015) for more information.

See the 2018 Faunalytics report titled “Attitudes Toward Farmed Animals In The BRIC Countries” for more information.

“It is estimated that 30% of Brazilian beef comes from clandestine slaughter, and a large percentage of the meat from authorized slaughterhouses does not undergo any inspection, since the mandatory presence of veterinarians is commonly ignored. The Ministry of Agriculture estimates that half of the beef consumed in Brazil originates from slaughterhouses without inspection or inspection by health authorities.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019.

See the Hong Kong Government Research Office’s fact sheet on Brazilian meat and meat products.

See the OECD Conference on Agricultural Knowledge Systems 2011 for more information.

We believe that language can have a powerful impact on worldview, so we avoid terms like “livestock” and “poultry” whenever possible. These terms are likely to contribute to a lack of awareness about the origins of food and could make it difficult for consumers to understand the effects of their food choices. That being said, the FAO data that we draw from in this report categorizes animals and meat in this way, so we will use the term “poultry” when referring to chickens, ducks, and turkeys for the sake of simplicity.

This data was procured from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

See data from Trading Economics 2018 and the World Bank 2018 for more information on employment in agriculture.

Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

See “Adoption of beef cattle traceability at farm level in São Paulo State, Brazil” by Vinholis et al. for more information.

From United States Department of Agriculture – Foreign Agricultural Service 2017. The report notes that domestic demand and export of pork from Brazil is also predicted to rise in the coming years.

We believe that language can have a powerful impact on worldview, so we avoid terms like “livestock” and “poultry” whenever possible. These terms are likely to contribute to a lack of awareness about the origins of food and could make it difficult for consumers to understand the effects of their food choices. That being said, the FAO data that we draw from in this report categorizes animals and meat in this way, so we will use the term “poultry” when referring to chickens, ducks and turkeys for the sake of simplicity.

The FAO defines “cattle” as “common ox (Bos taurus); zebu, humped ox (Bos indicus); Asiatic ox (subgenus Bibos); Tibetan yak (Poephagus grunniens). Animals of the genus listed, regardless of age, sex, or purpose raised.”

These totals are a sum of the species represented in the table. They exclude all fishes, insects, and some mammals such as rabbits.

Capture fisheries, or wild fisheries, refer to the harvesting of species from their natural environment. Conversely, aquaculture is defined by NOAA Fisheries as referring to “[t]he breeding, rearing, and harvesting of aquatic plants and animals. It can take place in the ocean, or on land in tanks and ponds.”

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2013 reports that fisheries and aquaculture represent only 0.5% of the GDP in Brazil. The Agricultural GDP in 2011 was worth $115 billion, whereas fisheries were comparatively worth just over $2 billion.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2013 reports that aquaculture has had very steady, long-term growth and therefore has significant potential to increase fish supplies in Brazil. From 1997 to 2007, aquaculture in Brazil grew by 330%, reaching a production total of 290,000 metric tons.

“Projections indicate an increase in the [fisheries] sector. [In a] report [by] the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), released in 2016, [it] estimates that the country should record growth of 104% in fishing and aquaculture by 2025. According to the study, the increase in Brazilian production will be the highest recorded in the region.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

The Brazilian Government hasn’t published official data about fisheries and aquaculture since 2007.

A 2009 Compassion in World Farming report titled “The Welfare of Farmed Fish” states that intensive aquaculture practices frequently expose fishes to a number of stressors such as handling, vaccinations, crowding, grading, loading, and transport. Intensively farmed fishes can suffer from a range of health and welfare problems including physical injuries, fin erosion, eye cataracts, skeletal deformities, soft tissue anomalies, sea lice infestation, and high mortality rates. It is well documented that fishes are capable of experiencing pain, fear, and distress, and that they have the capacity to suffer.

A 2017 Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy report titled “The Rise of Big Meat” states that these companies used a significant proportion of BNDES resources to acquire smaller companies and amass power. In 2008, there were 750 meat processing plants across Brazil; by 2015, more than 600 of them were in danger of disappearing due to domination in the sector by giant corporations.

A 2017 Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy report titled “The Rise of Big Meat” states that BNDESPar owns nearly 25% of JBS’s capital and the Brazilian public bank (Caixa Econômica Federal) owns a further 10%.

“JBS has 220 plants worldwide and employs more than 230,000 people in Brazil and abroad. The United States has 56 production units, accounting for more than half of the group’s revenues. […] Animal welfare measures adopted in the U.S. will likely affect more animals exploited by the company than measures adopted in Brazil. Likewise, economic sanctions or the measures that the American Courts may take in relation to corruption cases involving JBS are much more concerning for the company than the future of Brazilian economy. Over the past three years, the Batista brothers, owners of the company [JBS], were involved in several corruption scandals having being arrested more than once. There was also a rotten meat scandal which exposed sanitary issues with the meat sold by the company. BRF was also involved in both corruption and the rotten meat scandal. Several countries banned the imports of Brazilian meat in the wake of those scandals but most of the bans have been lifted subsequently.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

A 2017 Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy report titled “The Rise of Big Meat” states that JBS has seen rapid growth in recent years, increasing its food sales by 195% between 2011 and 2016. In addition, the concentration of cow slaughtering in the three main meat corporations rose significantly between 2006 and 2013—of these JBS raised its share the most from 6.5% to 27.9%. In Mato Grosso do Sul, JBS increased its share of the total meat processing capacity in the state from 47% to 61% between 2012 and 2015.

We believe that language can have a powerful impact on worldview, so we avoid terms like “livestock” and “poultry” whenever possible. These terms are likely to contribute to a lack of awareness about the origins of food and could make it difficult for consumers to understand the effects of their food choices. That being said, the FAO data that we draw from in this report categorizes animals and meat in this way, so we will use the term “poultry” when referring to chickens, ducks, and turkeys for the sake of simplicity.

A 2017 Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy report titled “The Rise of Big Meat” notes that BRF’s two largest shareholder are public pension funds; Petrobras Social Security Foundation owns 12.49% and the Banco do Brasil Employee’s Pension Fund owns 10.94%.

“Both companies [JBS and BRF] have also committed to a cage-free egg policy without the need for a campaign – both sell processed and frozen foods. Animal Equality led the negotiations for the cage-free eggs policy issued by both of the companies in 2017.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

See the 2015 Humane Society International article titled “JBS to Phase out Gestation Crate Housing for Breeding Pigs from Entire Supply Chain” for more information.

We believe that language can have a powerful impact on worldview, so we avoid terms like “livestock” and “poultry” whenever possible. These terms are likely to contribute to a lack of awareness about the origins of food and could make it difficult for consumers to understand the effects of their food choices. That being said, the source that we refer to here categorizes animals and meat in this way, so we will use the term “poultry” when referring to chickens, ducks, and turkeys for the sake of simplicity.

A 2014 World Animal Protection report states that Decree 24.645/1934 established protection for animals against ill treatment and cruelty. Article 3 of the decree prohibits conduct such as abandoning a sick, injured or mutilated animal, failing to provide for an animal, including veterinary assistance and denying a quick death free of suffering when a death is necessary, regardless of whether the animal is intended for consumption.

“There is a lot of discussion in the legal field surrounding the validity of such legislation issued […] during the period of the Provisional Government (1930–1934), instituted by the 1930 Revolution, before the adoption of a new Constitution. In 1991, the decree was revoked by President Collor. Some jurists dispute the validity of the revocation given that the 1934 decree was equated to a formal law given the particular political context of that time. But many believe it should not be invoked or referred to, in support of any procedure aimed at the protection of animals or penalties for the occurrence of ill-treatment of animals. Nevertheless, [due to] the lack of legislation establishing what is considered animal cruelty, the decree has been used more than once in legal cases concerning animal welfare. To establish legal security, and to consolidate legal protection for animals either a new legislation or the actualization or formal reception of this decree into the contemporary legal system is needed.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

According to a 2014 World Animal Protection report, this is outlined in Chapter 7, Article 225 of constitutional rule.

See the BBC article “Farra do Boi: mesmo proibida por lei, prática sangrenta ainda é comum em Santa Catarina,” which states that the Farra de Boi involves releasing oxen into the wilderness where participants then attack the animals. The oxen are pursued for hours, until they are exhausted, beaten with sticks, eyes pierced with spikes, and tails and ears ripped. Some break their bones in the despair of trying to escape. The event ends only when the animal is already exhausted and bruised to the point of no longer getting up. Although illegal, the practice still continues today.

The 2014 World Animal Protection report refers, among other things, to Article 32 of the Environmental Crimes Law 9605/98. The report states that the penalty for mistreatment or abuse under Article 32 is three months to one year imprisonment and a fine. However, there are exemptions under this law—for example, cruelty to animals is permitted when carried out in response to hunger or need.

“These guidelines are mere recommendations which are not legally enforced and often have no prescribed penalties or sanctions for noncompliance. Also there is no effective oversight by the authorities to ensure that animal welfare recommendations are being met, since government inspectors at present are trained to supervise solely sanitary issues and have no knowledge of animal welfare, generally speaking.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

The 2014 World Animal Protection report states that in November 2008, Instruction Number 56 was established. It lays out general principles of good practice relating to farmed animal rearing systems and transportation. Article 3 sets out general principles for welfare such as management through knowledge of animal behaviour, appropriate diet, properly designed production systems to allow for rest and welfare, appropriate handling and transport, and avoidance of unnecessary suffering. In addition to this, Decree 5,741 of 2006 requires documentation for the movement of animals with information on the destination, the health of the animal and the purpose of transport.

For more information, see the 2014 World Animal Protection report referring to Normative Instruction 03/2000 on Technical Regulation of Stunning Methods for Humane Slaughter of Meat Animals.

The 2014 World Animal Protection report states that the Federal Inspection Service of the Ministry of Agriculture is responsible for ensuring that slaughterhouses are abiding by the law. It carries out random inspections of facilities and records. Establishments breaching humane slaughter practices risk sanctions including fines and suspension of slaughter.

“[The Permanent Technical Commission on Animal Welfare] tends to have a more political than a truly technical role these days, and tends to defend economic interests rather than the welfare of animals. The Coordination of Good Practices and Animal Welfare continues working on animal welfare trying to improve the current regulations, but has very limited influence and power within the current government structure. The decisions on the issue of animal welfare are within the competence of the Department of Animal Health, which has a seat in the Technical Committee on Animal Welfare. The Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply is responsible for the promotion and monitoring of the welfare of farmed animals and those of ‘economic interest.’ The supervision is the responsibility of the departments of the Secretariat of Agricultural and Livestock Protection and promotion is the responsibility of the Coordination of Good Practices and Animal Welfare which is under the Secretariat of Social Mobility, Rural Producer and Cooperativism. With the supervision and inspection laying under the Secretariat of Agricultural and Livestock Protection, which represents economic and political interests of the sector, not much has been done to protect the welfare of animals. Ideally, animal welfare would not be under Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply but under the Ministry of Environment. However in the current political scenario this seems very difficult as the current President [Jair Bolsonaro] intended to merge the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply and the Ministry of Environment.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

The 2014 World Animal Protection report notes that the Permanent Technical Commission on Animal Welfare was established by Ordinance No. 524 from March 2011. The report also states that training projects are carried out by the government across hundreds of cities on topics such as humane treatment of animals during transport and slaughter. The Commission has 27 focal points working in the Federal Agricultural Superintendencies in all Brazilian states. They are intended to promote the development of working groups with livestock sector stakeholders to improve the Commission’s effectiveness on animal welfare across Brazil.

See the 2016 Business Benchmark on Farm Animal Welfare report titled “Animal Welfare in Farmed Fish” for more information.

The 2014 World Animal Protection report states that a lack of resources for areas other than the prioritized issues of transport and slaughter of animals for international trade is a potential barrier to making further progress towards the OIE standards. The government also faces logistical challenges to improving animal welfare. For example, most roads in Brazil are unpaved and in poor condition which leads to extended journey times and high likelihood of distress when transporting livestock.

“I believe this presents opportunities to work in collaboration with organizations in other countries which have higher animal welfare standards in advocating for the requirements of those higher standards for their imports. Brazil is currently on its way to approving a bill banning animal testing on cosmetics due the European Union pressure. The European Union announced it would ban imports from countries which allow animal testing and is currently discussing a global ban.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

“We have plans to lobby for the creation of a Secretariat of Animal Welfare which would be responsible for promoting, supervising, and inspecting animal welfare, and applying penalties for noncompliance. This Secretariat could work in partnership with selected NGOs across the country.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

See the 2018 Voiceless Animal Cruelty Index website for more information.

For more information, see the 2018 Humane Society International article titled “Historic meat reduction project launched in Bahia, Brazil.”

For more information, see our Conversation with Sandra Lopes of Humane Society International (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (2018).

By 2017, over 47 million meatless meals had been served as a result of the “Meatless Monday” program in Brazil.

For more information, see the Meat Free Mondays website.

See the 2018 Animal Charity Evaluators blog post titled “Roundtable: How Can we Effectively Help Animals in Brazil?” for more information.

For more information, see our Conversation with Lucas Alvarenga of Mercy For Animals (2018).

For more information, see the 2017 Mercy For Animals article titled “WOW! MFA’s Conscious Eating Program Will Serve 26 Million Vegan Meals Each Year.”

For more information, see our 2018 comprehensive evaluation of Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Patrycia Sato of Fórum Animal (2018). She also reported that currently, more than 90% of eggs produced in Brazil come from caged hens.

For more information, see our Conversation with Patrycia Sato of Fórum Animal (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Lucas Alvarenga of Mercy For Animals (2018).

“A survey commissioned by Greenpeace in 2017 and carried out by the biggest research institute in Brazil found that 73% of Brazilians consider themselves uninformed about meat production, indicating the potential for investigations in the country. Given how incipient animal rights is in Brazil and how ingrained meat culture is, I think it is worth considering diversifying the angles through which investigations are presented, […] for example, exploring health and environmental angles, or perhaps, land invasion and slave labor, on top of animal cruelty. [This has] a potential for a much greater reach than focusing solely on animal cruelty. Animal cruelty has to be part always of the narrative but adding other angles could guarantee much more media coverage and social impact.” —Private communication with Vivian Mocellin of Animal Equality, 2019

See the 2017 Animal Equality investigation, which was the first ever conducted into the egg industry in Brazil.