What elements of a leaflet matter?

The Humane League’s strong commitment to using evidence to maximize the effectiveness of their outreach efforts is one reason why ACE considers them one of the two most effective animal charities we’ve evaluated. We’re closely following the Humane League Labs as they release the results of several studies they’ve conducted over the past year. Their most recent report, What Elements Make A Vegetarian Leaflet More Effective?, covers the result of a study that intended to address whether the effectiveness of leafleting depended on the content of the leaflet used.

Results of the study

The Humane League tested eight different leaflet designs to see what characteristics would increase their effectiveness. They handed out surveys to 3,233 participants, most of whom also received a leaflet with the survey. Partway through the survey participants were instructed to stop and read the leaflet before finishing the survey. Three months later, they emailed all participants a second survey, to which 569 responded. While the initial survey included questions about both present diet and intended future diet, THL appropriately based their conclusions on the changes in the responses about present diet between the two surveys. They were able to track respondents between surveys, a very strong design for this type of study.

The eight treatment leaflets varied in several ways, with each possible combination of traits represented by some leaflet. While THL reported results of particular leaflets’ effectiveness, the sample size for any particular leaflet was small, so the results most likely to be robust are for comparisons of traits rather than of specific leaflets. As reported by THL, these were:

- Booklets focused on all animals were associated with more diet change than booklets focused only on chickens. This was the largest reported difference.

- Booklets focused on how to go vegan were associated with more diet change than booklets focused on why to go vegan. This result was reversed when only considering booklets also focused on all animals.

- Booklets focused on cruelty were associated with slightly more diet change than booklets focused on health.

The magnitude of all results was reported in average animals spared per year per booklet. Unfortunately, no significance tests or confidence intervals were reported, so while some differences were meaningful in a real world sense (for instance, booklets on all animals sparing a reported average of 4.4 animals per booklet vs. 1.8 animals per booklet focused on chicken), it’s not clear from THL’s write-up whether these differences are also statistically significant, meaning unlikely to have arisen by chance.

Results, crowd-sourced

One of the great strengths of the Humane League Labs research program is their commitment to making the full results of their studies, including anonymized raw data, publicly available. In this case, even though they didn’t report on the statistical significance of their results, we can check which results are significant ourselves. Rob Wiblin and Ben West have shared their efforts to determine which results are statistically meaningful on Facebook. The main results of their combined analysis, and my own, are:

- None of the three factors tested had a statistically significant effect on respondents’ reported change in consumption or red meat or poultry, or on their total reported consumption of animal products. Red meat and poultry were investigated separately because it would be consistent with other studies’ results for the only effects of leaflets to be on consumption of these products and looking only at total consumption might dilute these effects. Even though the respondents were randomly assigned to groups and tracked between surveys, we can’t infer that the content of the leaflets affected how much they changed their consumption, because the changes that appear to be due to content aren’t large enough compared to the overall variability of the data.

- THL noted that the control group had reported the most dietary change, but that because of the small size of this group this was a statistical anomaly. This was consistent with our statistical tests; whether respondents had received a leaflet at all appeared to be more of a factor than the content of the leaflet, but the effect was still small enough to be attributed to chance. In particular, in models predicting change in consumption of red meat, poultry, or all animal products only from whether the respondent had received any leaflet, the connection was strongest for poultry, with control group membership being a marginally significant predictor of increased reduction in poultry consumption (.05<p<.1).

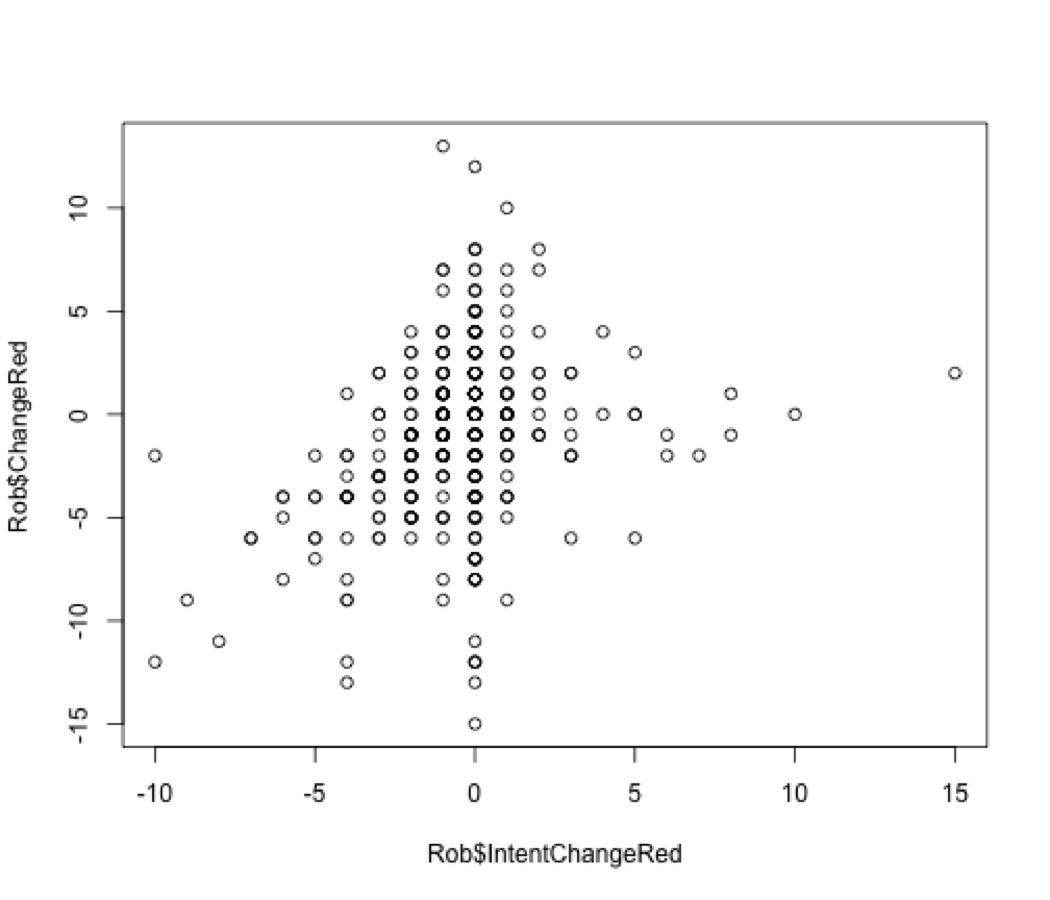

- Some other factors were connected to reduction of meat or animal product consumption. Specifically, younger people reduced consumption by a larger amount than older people. Also, the amount people intended to reduce consumption by was slightly correlated with their actual reported reduction in consumption, with people on average reducing overall animal product consumption by about ⅕ as much as they originally intended to (p<.01). These results were even more significant when restricted to red meat or poultry, and the decrease from intention to reality wasn’t as large: respondents reduced their consumption of red meat by about 55% as much as they intended and their consumption of poultry by about 40% as much as they intended. The strongest correlation was in the case of red meat, when intent to change accounted for about 9% of the variation in actual reported change.

How does this study affect what we think of leafleting?

This study has very little effect on our perception of the overall effectiveness of leafleting and on our understanding of what specific leaflets are likely to be most effective. It provides some weak evidence that the effects of leafleting are small (or possibly even negative), but we already believed the effects of leafleting to be difficult to detect with the sample sizes used in this study, and in particular with only 45 people in the control group who completed both surveys. The design of the study was also not naturalistic (participants read the leaflets in the presence of the surveyer rather than being handed a leaflet to read later). This further weakens the evidence it provides about the overall effectiveness of leafleting, though it is less of a concern for booklet-to-booklet comparisons within the study.

The evidence that the effects of content changes in leaflets are small is slightly stronger, though again, this is consistent with what we would have expected before. The one study we’re aware of that has found clear and significant effects of changing the specific outreach message used was The Humane League’s analysis of which videos used in online ads led to more Vegetarian Starter Kit clicks, which used data from a total of 83,000 views. The sheer number of views involved allowed that study to detect effects that would not be clear at this scale.

How does this study affect what we think of THL?

Overall, this study represents a step forward in THL’s survey methodology, and we view it as a positive sign about their increasing skill and sophistication when it comes to vegetarian advocacy research. While they still have room for improvement, they are willing to commit seriously to trying to understand the best ways to do what they do, and we believe this will ultimately pay off for them and for others in the movement.

Some positive aspects of this study:

- The selection of treatment and control groups, and the leaflets used in each case, were appropriate to the goals of the study. If the content of the leaflets distributed had any of the hypothesized effects at a scale large enough to detect with this sample size, this design would have produced clear findings about that effect.

- The method of measuring diet change was the strongest we have seen in any study carried out within the animal advocacy movement, including our own.

- The survey asked concrete questions about consumption of animal products in the week prior to the survey. There was relatively little room for respondents to interpret the questions in ways other than the one intended by the Researchers, and the demands on memory were reasonable.

- THL committed enough resources to the initial leafleting and surveying that they were able to track diet change by connecting the answers of the same respondents at the start and end of the study period. This eliminates concerns respondents providing the end data were systematically different in an unexpected way from respondents providing the starting data.

- As usual, THL shared all their data and findings from this study. This is valuable both as it provides information to others about anything that THL has learned from a study, and as it provides others with the opportunity to give feedback that may help THL in planning and conducting future studies.

In the spirit of constructive criticism, some aspects of this study that could be improved next time:

- Given the size of the effects of leafleting overall, and the assumption that differences in effects between leaflets would be smaller, it might have been possible to use a power analysis before this study was conducted to determine that its size would not be enough to reliably detect the effects of interest. This could allow THL to know where to concentrate their efforts, especially when considering a broad slate of possible studies. This is something we hope THL is considering for the future.

- Reporting statistical significance, confidence intervals, or other measures clarifying the robustness of results is important. Especially when results are significant in real-world terms, omitting these can lead to confusion about which results are reliable and how much results should be used to guide decision making.

As we’ve said before, research is hard! We’re glad that THL is taking on so much of it, and that they are sharing the results in a way that lets us benefit from both their findings and their difficulties.

Filed Under: Research

About Allison Smith

Allison studied mathematics at Carleton College and Northwestern University before joining ACE to help build its research program in their role as Director of Research from 2015–2018. Most recently, Allison joined ACE's Board of Directors, and is currently training to become a physical therapist assistant.

Second this. But I would more emphatically say that THLL has to change how it reports its results to reflect how strong the results are (if indeed they exist at all). Their original post reports findings which aren’t really there, and ought to be corrected to avoid misleading activists.

I look forward to talking with them tonight about how they can do proper statistical analyses in the future.