What Is the Value of Research?

This is the seventh post of our Foundational Questions series. You can read more about this project and see the initial post here.

Summary

We think research should be a high priority of the animal advocacy movement, partly because of the large impact it has in other cause areas such as aid to the global poor. However, the cost-effectiveness of research likely varies substantially depending on the methods and topics of research, and it’s possible that research in a complex, social field like animal advocacy is just too expensive and difficult to be highly cost-effective, or that it is too difficult to get advocates to change their strategies based on research results.

In order to make their research as impactful as possible, Researchers should ask themselves several important questions before beginning a project:

- Does an answer to this research question already exist?

- Would an answer to this research question allow animal advocates to have a much greater impact?

- Is there a good chance that this research method will provide relatively strong evidence?

- Will animal advocates pay attention to the results of this research and allow it to affect their strategy?

Currently, we think experiments and case studies (such as of a particular social campaign or movement) are usually the most promising research methods. We expect our understanding of the effectiveness of research to increase substantially in the future, especially because of the Animal Advocacy Research Fund.

The Impact of Research

The cost-effectiveness of research in effective animal advocacy (EAA) is usually based on three assumptions:

- There are important, unsolved questions about what works and what doesn’t for helping animals.

- Research can make significant improvements in our understanding of those questions.

- If one makes progress on those questions, advocacy groups and individuals will listen and make substantial changes to their strategies.

If each of these are true to a sufficient extent, research could be one of the highest impact uses of our resources. For example, in our 2015 evaluation of Faunalytics, we primarily thought of research as a multiplier on the impact of other organizations. It multiplies impact because, provided assumptions (1) and (2) are met above, research provides evidence that some approaches are substantially more cost-effective than others, and if assumption (3) is met, some number of organizations notice the results and have some probability of increasing the resources they spend on those approaches. Although those results aren’t definitive, the additional resources spent on those approaches have some chance of being more effective and therefore doing more good for animals.

Research can also have other impacts, such as by providing information to policy-makers to help them make the case for animal-friendly policies, but this is a less common route for impact.

A key qualitative argument for the impact of research is that there’s a relatively small amount of research in the animal advocacy movement as a whole right now, and given the benefit research has had in other fields like aid to the global poor, it seems likely that animal advocates should be doing much more research.

However, research in an area like animal advocacy is often very challenging. For example, we felt the recent study of online ads by Mercy For Animals had a strong methodology and was well-executed, but the guidance yielded by the results was still relatively weak due to the low statistical power. Overall, we think existing EAA research is just scratching the surface of potential opportunities, and additional research still seems potentially high-value.

Research Strategies

Experimental research like the MFA study is a useful way to collect objective data that can provide relatively strong causal evidence, at least of some short-term measurable outcomes. This will probably be one focus of the new Animal Advocacy Research Fund: to support studies that experimentally test the effects of particular strategies or interventions (e.g. leafleting) against a control group, or experimentally test the effects of different implementations of a strategy (e.g. appealing for gradual vs. immediate dietary changes in a leaflet).

One challenge of experimental research is that long-term studies are fairly expensive, at least relative to the budgets of many animal advocacy groups. Short-term studies, while cheaper, are limited in their application because short-term impact doesn’t necessarily translate to long-term impact. This also applies to the individual nature of most experiments, given the strong influence social forces have on human behavior. For example, a pro-veg eating advertisement might use messages that are optimized for short-term individual change, but those messages might be suboptimal for inspiring them to tell others about the issue, which is an important outcome and not usually measured in experiments.

Case study research, such as our ongoing study of historical social movements, has the advantage of accounting for many more outcomes than most experimental research. Especially if the case study is historical, it also presents its own challenges. We often have a low number of data points, and it’s difficult to tease out causation from other factors. For example, if several successful social movements have used confrontational tactics, the confrontation could be leading to the success, but another explanation is that some movements have particularly large amounts of passionate supporters, which leads to both success of the movement and more confrontation.

Researchers can also conduct case studies of other subjects, many of which are smaller in scope and impact than an entire social movement. For example, if we want to understand the potential of documentaries to effect social change, we could look at the example of Blackfish, a 2013 film that’s recognized as having a substantial effect on SeaWorld and public perceptions of using animals as entertainment. These smaller case studies have similar benefits and drawbacks.

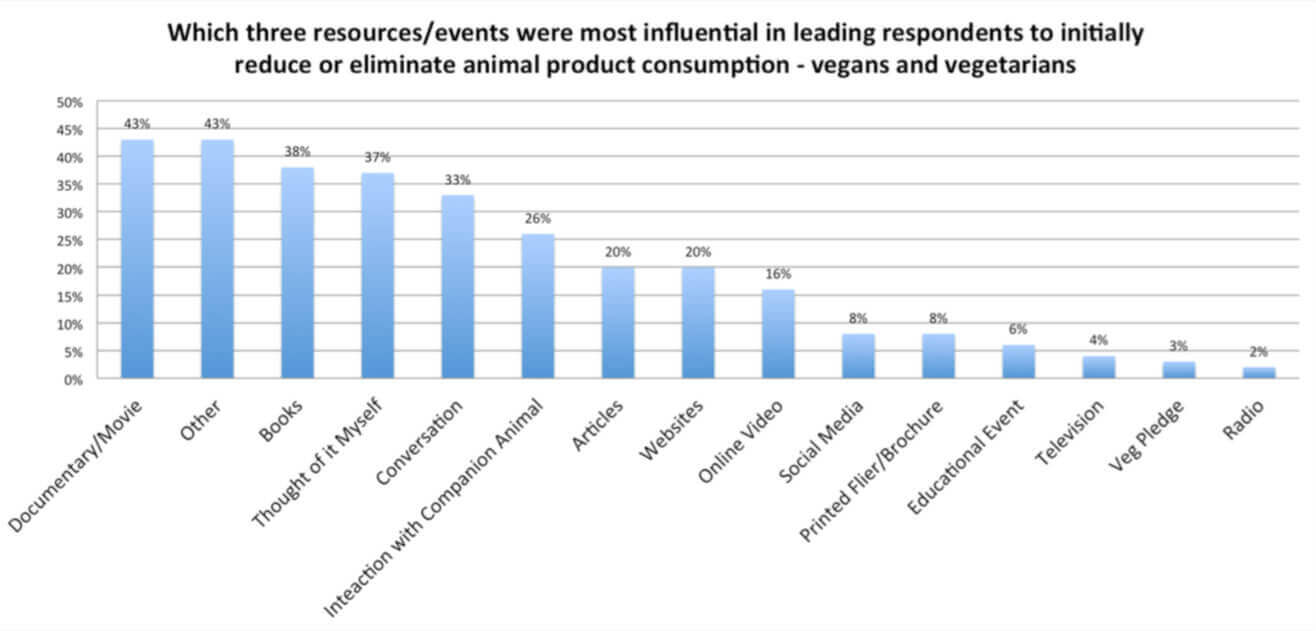

Survey research, such as a national survey asking vegetarians what facts led them to be vegetarian, seems to have limited usefulness. The main difficulty is connecting the correlational results to a conclusion about one advocacy strategy being more effective than another. For example, a 2013 survey asked vegetarians and vegans to list the top three causes for their change in diet. “Documentary/movie,” “Other,” “Books,” and “Thought of it myself” were the top four items.

However, even if showing people documentaries and books was a relatively ineffective form of outreach, we would expect similar results because (i) documentaries/movies and books are very easy to remember, (ii) these activities are common “second steps” after other factors have prompted dietary change, meaning they will be present for many people even if they weren’t a determining factor, and (iii) the number of people reached overall by documentaries and books about veg eating and factory farming could be higher than that of other forms of outreach.

We think survey research can be quite useful when providing instrumental information that informs other strategic decisions. For example, a 2014 survey of California consumers showed animal advocates that support for cage-free systems for egg-laying hens was very strong. This helped advocates plan their future campaigns and apply pressure to industry groups that opposed cage-free housing.

Moving Forward

We can look more closely at examples of social movements that have used research, or contemporary examples like the growing use of evidence in aiding the global poor. We can also look more closely at research in academia, such as political science or psychology, to see what new insights have been revealed and how much that research has cost.

The outcomes of the current Animal Advocacy Research Fund should also provide evidence, at least of experimental research. If these results turn out well — they lead to actionable conclusions that are taken seriously by animal advocates — and there are still open and important questions that can be answered through experiments, then we will prioritize this kind of work more heavily in the future.

About Jacy Reese

Jacy spends most of his time researching and promoting effective social change. He's been active in the effective altruism community for many years and would love to talk to you about how you can do the most good with your career, donations, or activism.

ACE is dedicated to creating a world where all animals can thrive, regardless of their species. We take the guesswork out of supporting animal advocacy by directing funds toward the most impactful charities and programs, based on evidence and research.

Join our newsletter