Aquatic Life Institute

Recommended Charity

ACE proudly recommends Aquatic Life Institute (ALI) as an excellent giving opportunity. ALI carries out a variety of short-term and long-term strategies aimed at reducing the significant suffering experienced by both farmed and wild-caught aquatic animals. These animals are among the most neglected in animal advocacy, despite their numbers being greater than all land animals combined. ALI uses robust logic to develop their programs and has a strong track record of success. Our cost-effectiveness assessment indicates that they have been able to help many animals at a relatively low cost. For example, through their corporate outreach program, we estimate they have reduced the suffering of thousands of shrimps for every dollar spent. ALI’s plans for 2025 and 2026 give us confidence that they would use donations in ways that are likely to create the most positive change for aquatic animals.

| Review Published: | 2024 |

Creating a better future for the trillions of aquatic animals farmed and caught in the wild for human consumption each year.

What does Aquatic Life Institute do?

Aquatic Life Institute (ALI) works to improve the welfare standards of farmed fishes, aquatic invertebrates (e.g., shrimps and octopuses), and wild-caught aquatic animals. They engage global institutions to achieve global reforms and provide guidance to aquaculture certifiers to improve welfare standards for farmed fishes and shrimps. Additionally, they work to strengthen the animal advocacy movement by running the Aquatic Animal Alliance, a global coalition that aims to improve aquatic animal welfare through united efforts in corporate and public policy.

2023 revenue: $648,814

Staff size: 9 (8 full-time, 1 part-time)

Year founded: 2019

How does ALI create change for animals?

Trillions of aquatic animals are farmed or caught in the wild for food, and evidence indicates that they suffer immensely. ALI works on campaigns that are likely to bring both significant short-term benefits and longer-term systemic change to relieve the suffering of farmed and wild-caught aquatic animals. They do this strategically through successful engagement with a range of influential stakeholders throughout the supply chain, including policymakers, retailers, and certifiers. ALI’s achievements through their corporate outreach program demonstrate that they are able to improve the lives of many aquatic animals cost-effectively—for example, their work reduces the suffering of nearly 5,000 shrimp per dollar spent. Their launch and maintenance of the Aquatic Animal Alliance seem particularly effective as a strategy to promote political progress on viable, evidence-backed welfare priorities. Through both their own work and their engagements through the Aquatic Animal Alliance, they were able to encourage better conditions for aquatic animals on 30 different policies over the previous calendar year.

See more details in ALI’s theory of change table and cost-effectiveness spreadsheet.

See our How We Evaluate Charities web page for information about our charity selection, evaluation methods, and decision-making process.

How is ALI’s organizational health?

Our assessment indicates ALI has positive staff engagement (average staff engagement survey score = 4.9/5) and is operating in ways that support their effectiveness and stability. They have a solid process in place to evaluate leadership performance, an independent board that meets regularly, and they actively prioritize organizational health. Staff positively noted Aquatic Life Institute’s inclusive, supportive, and empowering work culture. For more details, see their comprehensive review.

How will ALI use your donation to help animals?

ALI would prioritize using additional funding to hire more staff. Among other things, this would allow them to strengthen their certifier outreach and policy work and the impact of the Aquatic Animal Alliance. This will help them increase their capacity to help even more farmed and wild-caught aquatic animals and ensure that aquatic animal policies include important welfare commitments. We estimate that these uses of funding will be highly effective up to roughly $0.4M annually in 2025 and 2026, and that ALI’s total annual funding capacity is roughly $1.2M. By supporting ALI, you play a crucial role in helping them achieve their goals and creating a better experience for aquatic animals around the world. See more details in ALI’s Financials and Future Plans spreadsheet.

This review is based on our assessment of Aquatic Life Institute’s performance on ACE’s charity evaluation criteria. For a detailed account of our evaluation methods, including how charities are selected for evaluation, please visit our How We Evaluate Charities web page.

Overall Recommendation

Aquatic Life Institute (ALI) carries out a range of short-term and long-term strategies to help aquatic animals, supported by robust logical reasoning and a strong track record. Our cost-effectiveness assessment of two of their programs indicates that they have executed their activities cost-effectively to date. Through their corporate and institutional outreach program, they have ensured the pre-slaughter electrical stunning of almost 5,000 shrimps per dollar. Through both their own work and their Aquatic Animal Alliance engagements, they were able to give feedback and push for better conditions for animals on 30 different policies in the previous calendar year (the average cost for each policy engagement was approximately $10,000). ALI’s plans for how they would spend additional funding across 2025 and 2026 give us confidence that they would use additional funding in ways that create the most positive change for aquatic animals. We have no concerns about their organizational health: Based on our assessment, they appear to have robust processes in place and a high level of staff engagement. Overall, we expect the Aquatic Life Institute to be an excellent giving opportunity for those looking to create the most positive change for animals.

To support Aquatic Life Institute, and all of ACE’s current Recommended Charities, please consider donating to our Recommended Charity Fund.

Overview of ALI’s Programs

During our charity selection process, we looked at the groups of animals ALI’s programs target and the countries where their work takes place. For more details about our charity selection process, visit our Evaluation Process web page.

Animal groups

ALI’s programs focus on helping farmed animals and wild animals, which we assess as high-priority cause areas.

In particular, ALI focuses on helping both farmed and wild-caught aquatic animals. In 2023, they mostly focused on finfish and decapods.

Countries

ALI’s headquarters are currently located in the United States. They have a subsidiary in France.

ALI conducts their work globally. They engage in policy and corporate outreach work in many different countries and international organizations, such as the E.U. and the U.N. Estimates show that around 124 billion fishes are farmed in the world annually,1 with an additional total of 1.56 trillion wild-caught fishes in a year, not including bycatch and discards.2

Interventions

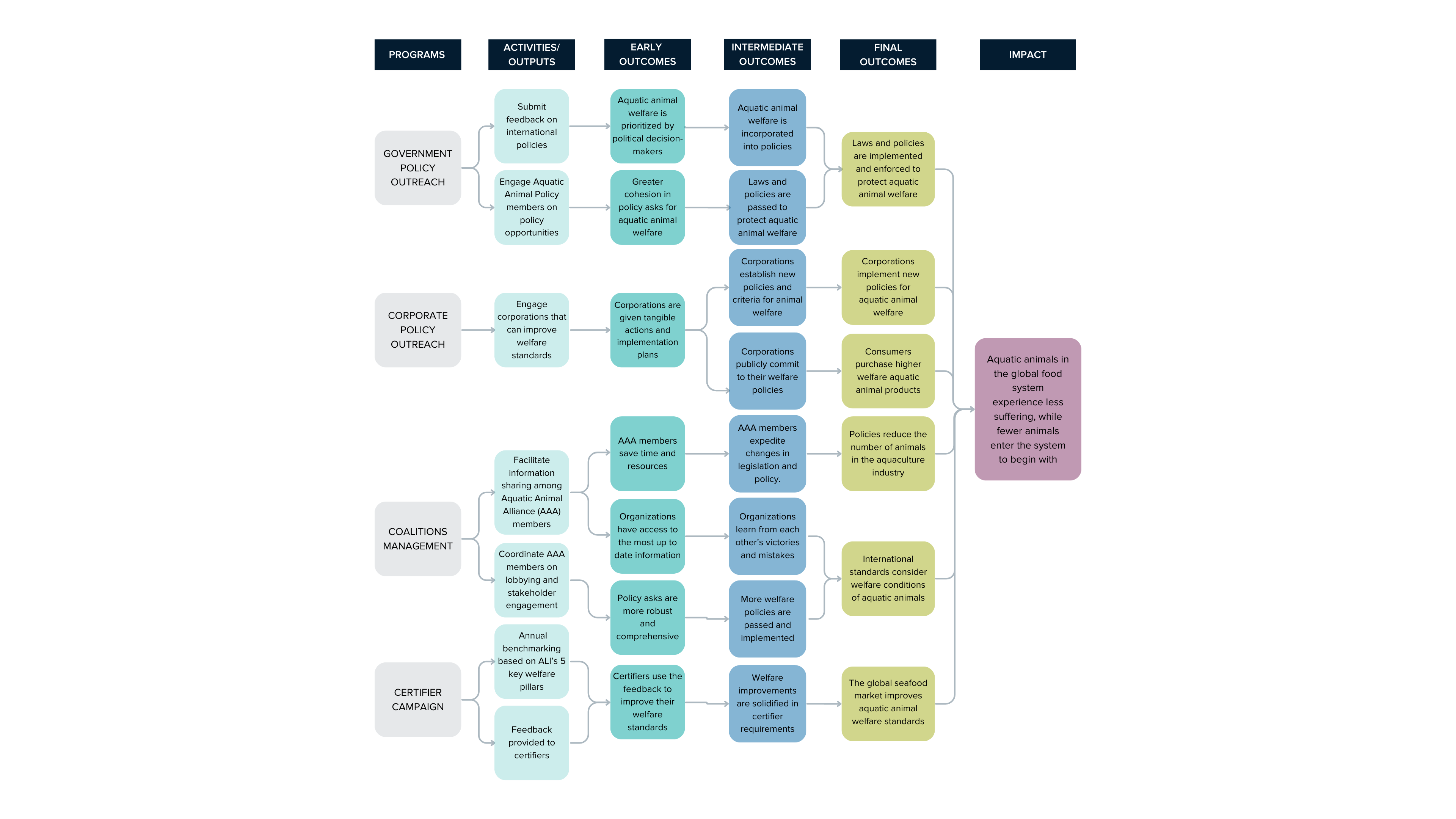

ALI uses different types of interventions to create change for animals, including: institutional and corporate outreach for welfare improvements, government outreach, network building, and producer outreach. See ALI’s theory of change analysis for evidence of the effectiveness of their main interventions.

Impact

What positive changes is ALI creating for animals?

To assess ALI’s overall positive impact on animals, we looked at two key factors: (i) the strength of their logical reasoning and evidence for how their programs create change for animals (i.e., their theory of change), and (ii) the cost-effectiveness of select programs. Charities that use logical reasoning and evidence to develop their programs are highly likely to achieve outcomes with the greatest impact for animals. Charities with cost-effective programs demonstrate that they utilize available resources in ways that likely make the biggest possible difference for animals per dollar. For more detailed information on our 2024 evaluation methods, please visit our Evaluation Criteria web page.

Assessment of ALI’s impact

Based on our evaluation and consideration of the risks and limitations, there is a moderate-to-strong level of logical reasoning and evidence supporting how ALI’s programs create change for animals.

We positively note that:

- ALI appears to have strategically chosen their policy, corporate, and certifier outreach campaigns to bring about both short-term benefits and longer-term systemic change. Especially for a relatively under-explored area like aquatic animal welfare, pursuing a strategically chosen range of tactics throughout the aquatic animal supply chain seems particularly important.

- ALI focuses on animals that are farmed and killed in particularly high numbers (predominantly fishes and shrimps).

- ALI appears to have a promising track record of successful engagement with policymakers, retailers, and certifiers.

We are particularly impressed by ALI’s launch and maintenance of the Aquatic Animal Alliance (AAA). This seems likely to bring significant value to ALI’s other activities, particularly their political outreach work, where ALI was able to provide several examples of the AAA’s significant contributions to policy progress. We think that uniting organizations behind a small set of evidence-backed policy asks for aquatic animals, securing support from over 100 organizations for those asks, and making it easier for organizations to launch their own individual aquatic animal advocacy campaigns is likely to be highly impactful.

We are somewhat less confident in ALI’s certifier outreach program compared to their other programs. This is mainly because there does not currently seem to be sufficient incentive for most certifiers to compete against one another to achieve high scores on ALI’s benchmark. However, we think that targeting certifiers is a promising approach in principle and positively note that this program seems to have contributed to some helpful amendments to certain certification welfare standards that could be built on in the future. ALI also reports that they are working to strengthen the incentives for certifiers to compete in the benchmark ranking.

Our cost-effectiveness assessment focuses on two of ALI’s programs, their corporate outreach and their policy work, which represent a limited part of the charity’s work. While our analysis includes areas of speculation, the cost-effectiveness estimate of ALI’s corporate outreach program is 481 Suffering-Adjusted Days (SADs) averted per dollar,3 which seems to be very high based on Ambitious Impact’s interpretation of SADs averted per dollar.4 In the case of ALI’s policy work program, they achieved approximately one engagement (e.g., presenting at conferences, providing feedback for policies, providing guidance, sending letters, etc.) for every $10,000 dollars. Due to the longer timelines and lower-probability, higher-impact nature of policy work, we did not estimate the SADs for this program.

Our cost-effectiveness estimates for the corporate outreach and policy outreach programs have limited explanatory power and should be interpreted with caution because of the relative uncertainty around shrimps’ capacity for pleasure and suffering, additional benefits of ALI’s work that were not quantified in our cost-effectiveness analysis, and the estimated duration of ALI’s impact. As a result, we gave limited weight to this cost-effectiveness analysis in our overall assessment of ALI.

See our theory of change table for a detailed account of ALI’s activities, outputs, and intended outcomes and impact. Below, we highlight the key activities that we believe are the most impactful drivers of their theory of change and give details on the reasoning and evidence base, as well as an account of risks, limitations, and mitigating actions.

Key Activity 1: Policy feedback

Activity description: ALI submits feedback on local, national, and international policies focused on improving aquatic animal welfare, with a particular focus on the E.U. and international bodies such as the U.N. They do not focus on a particular species; instead, they search for viable policy opportunities across all aquatic animals. They typically secure support for this policy feedback from members of their Aquatic Animal Alliance; see the Key Activity 3 section for more details of ALI’s coalition management.

Supportive reasoning and evidence base

- There are over 85 billion farmed fishes alive at any one time globally, of which there are over 930 million in the E.U., where much of ALI’s policy work takes place.5 Over 1.5 trillion fishes are caught in the wild each year for human consumption and animal feed, of which 85 billion are caught in the E.U.6

- There are an estimated 230 billion farmed shrimps alive at any point in time, which is higher than the estimates for any other farmed animal, including farmed insects. Twenty-five trillion wild shrimps are slaughtered annually.7

- Policy work plays a promising role in the animal advocacy movement. Animal Ask has written a report highlighting lobbying through public consultation (one of the kinds of policy outreach that ALI engages in) as a promising avenue for animal advocacy organizations.8 As part of their Charity Entrepreneurship program, Ambitious Impact has highlighted the potentially large impact of influencing E.U. fish welfare policy, supported by corporate engagement and collaboration with farmers.9 Rethink Priorities has specifically selected policy reform for farmed fish in the European Union as a potentially high-priority strategy.10 In this ACE report, we outline the potential role of policy outreach work more broadly in ensuring long-term change, influencing public attitudes, and fostering cultural shifts that benefit animals, as well as granting animal advocacy groups greater legitimacy in the eyes of policymakers.

- Evidence indicates that successful policy outreach can require action on multiple fronts.11 As such, we note positively ALI’s decision to facilitate close collaboration with other NGOs and lead policy outreach from multiple organizations through their Aquatic Animal Alliance, supported by their Aquatic Animal Policy focus group.

- Policy changes can have spillover effects to other countries. For example, countries with robust animal welfare laws may seek to include animal welfare considerations in trade agreements or ban the sale (as opposed to just the production) of low-welfare products within their jurisdiction. The E.U. appears to be particularly influential in this regard, with the global impact of E.U. market regulation sometimes described as the “Brussels effect.”12 For example, research has indicated that Argentina and Brazil tend to introduce animal welfare legislation that mirrors E.U. laws.13 As such, we positively note ALI’s decision to prioritize work at the international level, with a particular focus on the E.U.

- Though public support for animal welfare does appear to correlate with robust animal welfare legislation, studies across many countries have found public support for stronger animal welfare legislation even where this sentiment does not bear out through purchasing habits.14 This phenomenon, known as the voter-buyer gap, indicates that leveraging citizens’ existing values in support of progressive legislation could be a more effective route than seeking to change individuals’ consumption habits to achieve the same end.15

- ALI reports providing over 30 pieces of feedback in 2023 and around 22 in 2024 (as of September 2024).16 They report several examples of successful policy implementation based on their feedback. This includes successfully advocating for the inclusion of welfare considerations for both farmed and wild-caught fish in the E.U.’s upcoming 2026 Common Fisheries Policy. They also shared a paper they wrote on the need for humane stunning of fishes with Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), resulting in positive feedback from two and a meeting with one of those to engage further on this.

- ALI also works to prevent emerging industries from taking hold. For example, they appear to have played a significant role in securing the ban on octopus farming in Washington state, the first such ban in the world that we are aware of.17

Risks, limitations, and mitigating factors

- Limitation: Aquatic animal welfare science is a relatively young field compared to other commonly farmed animals, so there is somewhat less certainty about how changes in farming practices translate to experienced welfare improvements for the animals. There are also so many different species of aquatic animals that it can be particularly difficult to improve conditions for multiple species with one single intervention. This makes it hard to identify the most impactful and feasible interventions to prioritize in policy outreach.

- Mitigating factors: ALI reports that they synthesize the research they find and share it in an accessible manner with the members of their coalition and focus groups to help ensure that members are aligned on the current best practices and asks. They currently do this through email newsletters to the Aquatic Animal Alliance and Aquatic Animal Policy focus group. They also plan to do so through their forthcoming Aquatic Animal Alliance online member hub. They note that the “five welfare pillars” that inform their work are backed by data and align with the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals.18 We also note that two of these pillars (water quality and stocking density) are prioritized by one of ACE’s evaluated charities, Fish Welfare Initiative, based on their own evidence reviews and farm visits.

- Limitation: It is generally hard for organizations to both monitor the success of policy outreach efforts and pinpoint their individual responsibility for a particular policy success when several organizations have been involved in outreach efforts.19 This can make it hard for charities to identify how best to improve the likely impact of their work in the future. For this reason, it can be advisable to carry out an assessment of the policy ask (considering factors such as the national context, possible flow-through effects, and feasibility) to determine how cost-effective policy outreach is likely to be in each case.20

- Mitigating factors: ALI speaks to policy experts to understand the likely impact of the policy work that they undertake. They consult and brainstorm with others to develop joint actions, such as engagement with Eurogroup for Animals subgroups, the Aquatic Advisory Council, their own policy advisors, and other NGOs. In certain contexts, these conversations can help them gauge the status of their input and how it is shaping policy in real-time. ALI is interested in further monitoring their impact and plans to commission external Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) support when they have sufficient funds to do so.

- Limitation: Policy work often has a very small chance of success, especially for issues such as aquatic animal welfare, where there is little political will and understanding, a lack of public awareness, and pushback from the animal agriculture industry.

- Mitigating factors: As noted above, ALI seeks to maximize their chances of success by collaborating with other organizations and leading action through their Aquatic Animal Policy focus group. They campaign at local, national, and global levels, employing various tactics such as attending meetings, providing written feedback, and participating in international forums. Their outreach efforts concentrate on policies that appear to be the most achievable and impactful, rather than adhering to a “single-issue” focus.

- Limitation: Policy development can progress at a very slow pace. Legislation might become law but not be implemented for several years, or at all, due to insufficient oversight, enforcement, and corporate transparency.

- Mitigating factors: ALI pursues a variety of short-term and longer-term activities, to ensure that they are pushing for long-term reform while also maintaining momentum and bringing about more immediate benefits for aquatic animals.

Key activity assessment

Overall, taking into account the limitations and mitigating factors, we assess the logic and evidence of this key activity as moderate to strong. We positively note that:

- There is strong evidence supporting the potential impact of policy outreach work.

- The Aquatic Animal Alliance and Aquatic Animal Policy focus group appear a very promising way of uniting many organizations behind a single ask, thereby increasing the chance of success.

- ALI appears to have a strong track record of productive engagement with policymakers.

- ALI has a strong focus on the E.U., which seems like a particularly influential target in terms of the number of animals potentially affected by legislation both within the E.U. and globally due to the “Brussels effect.”

- While we note the limitations of policy outreach in general, we are convinced by the mitigating actions that ALI is taking to address these.

While we appreciate how ALI consults with policy experts to inform their policy asks and their intention to increase their investment in future MEL, they currently appear to lack a systematic method for assessing the impact of their policy outreach program or concrete plans for implementing such an assessment in the future. That said, we recognize that this is a difficult ask for organizations, especially given competing priorities and limited capacity.

Key Activity 2: Corporate engagement

Activity description: ALI partners with major retailers to encourage them to publish and implement aquatic animal welfare commitments. In practice, this has been mainly focused on commitments for shrimp welfare in the U.K. to date, though commitments have also covered finfish and octopuses.

Supportive reasoning and evidence base

- As detailed in Key Activity 1, a huge number of fishes and shrimps are farmed and slaughtered annually.

- To date, ALI’s corporate outreach work has mainly focused on retailer shrimp welfare commitments in the U.K. We estimate that U.K. retail customers consume around 94.2 billion shrimps each year (the vast majority of which are imported).21

- As a general point, most evidence on the effectiveness of corporate welfare reforms relates to chickens, especially egg-laying hens, and it is unclear how well this generalizes to other species. In this section, we have sought to provide evidence on aquatic animals where possible, but such specific evidence is relatively lacking.

- Corporate outreach for welfare improvements appears to have a strong track record of success, playing a crucial role in welfare improvements for hundreds of millions of animals. For example, the Open Wing Alliance reports that, as of May 2024, 89% of cage-free egg commitments with deadlines of 2023 or earlier have been fulfilled, and Open Philanthropy reports that 220 million laying hens are out of cages thanks to corporate welfare campaigns.22 A 2019 report by Rethink Priorities estimates, with various caveats, that historic corporate campaigns affected 9 to 120 years of chicken life per dollar spent.23 Evidence supporting aquatic animal welfare improvements is more limited, but there are some examples; for example, Shrimp Welfare Project estimates that their pre-slaughter electrical stunning advocacy helps, on average, between 1,100 and 2,200 shrimps per dollar spent, and a 2024 report by Rethink Priorities estimates that future marginal spending on farmed fish stunning corporate commitments in France, Italy, and Spain could potentially benefit between two and 36 animals per dollar spent.24 However, as noted in the Risks, limitations, and mitigating factors section below, the actual welfare improvements for each fish could be considered quite minor given the short duration of slaughter.

- It seems likely that corporate campaigning can pave the way for beneficial legislation. This perspective has been expressed by several leaders in the movement (such as in ACE’s conversation with David Coman-Hidy), with the E.U.’s previous proposed legislation banning cages being cited as a specific example.25

- The available empirical evidence on the effects of welfare reforms on public attitudes toward animal welfare suggests that such effects are either negligible or slightly positive, i.e., tending toward promoting pro-animal attitudes rather than promoting complacency.26 Despite this, it appears pragmatic to position corporate welfare reform campaigns as part of a longer-term trajectory to a future free from animal exploitation rather than an end goal.27 This aligns in principle with ALI’s ‘4R’ approach to seafood system reform, which prioritizes the reduction of the number of animals in the seafood supply chain; see the Risks, limitations, and mitigating factors section for further discussion on this.28

- In the long term, while evidence is mixed, it seems likely that corporate welfare reforms can be expected to drive up the costs of producing animal products, which will ultimately be borne either by consumers or at other stages throughout the supply chain, while also in principle making the sector less appealing for new entrants.29 While demand for animal products is considered relatively price inelastic, increasing the price of animal products does seem to decrease consumption, though evidence is fairly limited.30 As such, in theory, raising costs for the animal agriculture industry should make it less profitable and sustainable, especially given that it already tends to operate on very thin profit margins.31

- ALI reports adopting a “good cop” or “solutions broker” approach, noting that this is opposed to the history of more hard-hitting “bad cop” campaigns against the aquaculture industry that have predominantly come from the conservation movement. ALI reports using this approach to persuade companies of the positive case for welfare improvements (for example, by pointing to rising consumer interest in higher-welfare products, the benefits of staying ahead of future animal welfare legislation, and the growing role of animal welfare in the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards expected of companies) and supporting them in implementing these. Reports by Social Change Lab and Animal Ask suggest that organizations specializing in different approaches so that they can collectively exercise a “good cop, bad cop” approach can be an effective strategy.32 ALI reports that they will consider collaborating more with “bad cop” organizations in the future to increase the effectiveness of their work.

- ALI reports specific corporate welfare improvements based on their advocacy work; for example, the U.K. retailers Waitrose and Marks and Spencer introduced welfare commitments affecting large numbers of shrimp following outreach by ALI and several other organizations.33 As more expensive, vocally ethical retailers, we expect they would have introduced such a policy within the next few years anyway, but we are convinced by ALI’s reasoning that their work probably helped to bring these commitments forward, reduce the risk of “humane-washing” in those commitments, and increase the likelihood of implementation. Most recently, ALI contributed to Tesco’s decapod welfare policy and supported Hilton Foods in drafting their crustacean welfare policy, in which ALI is named as the company’s main partner.34 They also supported the major seafood producer BlueYou in drafting their animal welfare policy.35

- ALI also engages with industry through various channels to boost their credentials. They have participated in various industry events, including the Barcelona Seafood Expo and the World Fisheries Congress. Their involvement extends to the Pelagic Advisory Council, which provides direct advice to the European Commission. They have also been invited to serve as a council member for the Global Dialogue on Seafood Traceability and are part of the Technical Working Group for the Aquaculture Stewardship Council.

Risks, limitations, and mitigating factors

- Limitation: ALI’s reasoning relies in part on consumers’ increased willingness to pay (WTP) for aquatic animal products that are labeled as higher welfare. There is some evidence to support consumers’ increased WTP for higher-welfare products generally, but it cannot be assumed that consumers’ hypothetical WTP will bear out in real-world settings.36 For example, while 70% of people in the U.S. report paying attention to animal welfare labels, over 99% of farmed animals in the U.S. are factory-farmed.37 We are also not confident in consumers’ ability to distinguish between different certifiers, given the general public’s apparent confusion surrounding welfare labels.38 Similarly, a systematic review in Asia, where most aquatic animals are farmed and consumed, suggests that sustainable practices and ecolabels exert relatively little influence on consumer behavior compared to other factors.39 This appears likely to be even more pronounced for aquatic animals given consumers’ lack of understanding of their production and welfare requirements.40 Similarly, the Food Industry Association’s 2023 ‘Power of Seafood’ report concluded that 43% of consumers in the U.S. only partly understand or aren’t sure what “wild-caught” means, 51% don’t know what “farm-raised” means, and 71% don’t understand the term “aquaculture.”41

- Mitigating factors: ALI acknowledges that consumer understanding of welfare labels is limited. As such, they seek to use a “top-down” approach by engaging directly with retailers, given that retailers’ welfare improvements shape consumers’ purchases indirectly and can raise consumers’ awareness of aquatic animal welfare. They use arguments to convince retailers to change their welfare practices that do not solely rely on their consumers’ existing interest in higher-welfare aquatic animal products, such as the benefits of staying ahead of upcoming progressive welfare legislation and expectations around ESG standards.

- Risk: In practice, ALI’s focus is mostly on welfare improvements, where they expect to be able to make the most impact. Some of the welfare improvements that ALI helps companies implement can save the companies costs in the long run, potentially making aquaculture more financially viable and ultimately increasing the number of animals intensively farmed. This is significant given the huge, growing number of fishes and shrimps farmed each year and the increasing trend of governments promoting aquaculture as a supposedly sustainable way to improve health and economic development.42

- Mitigating factors: While ALI acknowledges this as a risk, they note that their ultimate goal and overarching “4R approach” is to reduce the number of animals farmed and encourage alternatives such as plant-based seafood.43 In line with this approach, alongside their welfare improvement work, they also pursue some more anti-speciesist work (such as advocating for insect and octopus farming bans through their political and certifier outreach programs, advocating for plant-based fish feed in their research publications, and advocating for a shift to animal-free aquaculture in outreach with development banks).44 In practice, their welfarist work has been a priority to date, as ALI feels better equipped to make progress on such asks.

- Limitation: It is possible that ALI will only be successful in influencing higher-end retailers and be unable to engage lower-cost retailers.

- Mitigating factors: ALI notes that given the relative infancy of the aquatic animal welfare movement, they do not expect to run out of higher-end retailers to engage in the next few years, especially with their global focus. They also note that some of the largest low-cost U.S. retailers—including Walmart, Kroger, and Meijer—have voluntarily pledged to transition to 100% cage-free egg sales in their stores, indicating their openness to general animal welfare improvements.45 They also note that Walmart and Sam’s Club have announced stronger standards for their tuna supply chain to address issues such as accidental catch of non-targeted species; while a relatively minor improvement in itself, this could be a promising precedent for more ambitious aquatic animal welfare improvements in the future.

- Limitation: Stunning commitments only affect a short duration of an animal’s life. For example, the Rethink Priorities report mentioned above estimated that future marginal spending on farmed fish stunning corporate commitments in France, Italy, and Spain would only improve 0.4 to 10 fish hours per dollar spent.46

- Mitigating factors: Such commitments are still significant if one considers the intensity of the suffering endured (which is likely to be considerably higher during slaughter than at other stages of life). They can also serve as achievable short-term wins that NGOs can pressure companies to expand on in the future to cover a greater period of the fishes’ lives.

- Limitation: Most aquatic animals are produced and sold in regions where corporate engagement is likely to be much more restricted and less feasible, such as China.

- Mitigating factors: While ALI notes this is true to an extent, they also note that retailers in any region are likely to source aquatic animal products from multiple other regions, yielding potential welfare improvements in those regions.

- Limitation: Companies may resist implementing new welfare standards due to perceived costs, complexity, or disruption to current operations.47 The complexity of international seafood supply chains can also make it difficult for corporations to implement and monitor aquatic animal welfare standards consistently.

- Mitigating factors: ALI reports providing companies with evidence of the long-term benefits of animal welfare commitments, including improved sustainability, brand reputation, and potential market advantages, and forms long-term relationships with companies in an effort to convince them. They also report offering free consultancy and relevant resources. Although this program began only in 2023, ALI reports that they plan to leverage their supply chain relationships in the future to assist retailers in sourcing high-welfare products.

- Limitation: Companies often make superficial or misleading claims about their animal welfare practices without actually making or enforcing meaningful improvements.48

- Mitigating factors: ALI encourages retailers to work with high-ranking certifiers, whose suppliers must be audited by independent third parties and meet strict guidelines and traceability standards (see Key Activity 4 below).

Key activity assessment

Overall, taking into account the limitations and mitigating factors, we assess the logic and evidence of this key activity as moderate. We positively note that:

- ALI appears to have a track record of productive engagement with companies.

- This work aligns well in principle with ALI’s certifier work (see Key Activity 4 for more information).

- Corporate outreach generally has a strong evidence base.

- This work is currently in its very early stages, and we would expect it to become more impactful in the future as ALI refines their asks and approach and strengthens their relationships with retailers and other industry stakeholders.

Potential challenges include:

- It is challenging to know how much credit to attribute for the corporate commitments secured, given that ALI was working alongside several other organizations.

- The likely impact of corporate outreach for aquatic animal welfare is somewhat lessened by the fact that corporate outreach may be less effective for animal agriculture industries (such as aquaculture) where there is less consumer interest, there are fewer well-established welfare asks, and supply chains are more complex.49

- While ALI has an anti-speciesist approach in theory and has some significant examples of such work, in practice, their work has focused more on incremental welfare improvements that could, in principle, stand to benefit the industry financially (although we do appreciate the strategic reasons for such an approach).

- We are uncertain about consumers’ engagement with higher-welfare aquatic animal products, which seems like an important part of the theory of change for getting retailers to improve their standards even if ALI also uses other arguments to persuade retailers to do so.

Key Activity 3: Coalition management

Activity description: ALI launched and runs the global Aquatic Animal Alliance (AAA).50 As of September 2024, the alliance consists of approximately 145 organizations dedicated to improving aquatic animal welfare. ALI seeks to use AAA to secure signatures from its members when providing policy feedback to political decision-makers. Additionally, the alliance supports organizations looking to run their own local advocacy campaigns, shares resources, and unites organizations around a cohesive set of welfare objectives. This initiative is supported by ALI’s smaller, more informal Aquatic Animal Policy focus group, which is comprised of individuals who meet on an ad hoc basis to discuss policy outreach priorities.

Supportive reasoning and evidence base

- As detailed in Key Activity 1, a huge number of fishes and shrimps are farmed and slaughtered annually.

- Research on the effectiveness of coalition building between organizations comes mostly from outside of animal advocacy. For example, a review of evidence on network building to improve capacity in nonprofits found that collaborative efforts enable nonprofits to solve complex problems more efficiently, spread innovative approaches, and leverage shared resources to enhance organizational development, infrastructure, and impact.51 This review also suggests that inter-organizational network building may be more effective when (as is the case with ALI’s Aquatic Animal Alliance and Aquatic Animal Policy focus group) networks explicitly share learnings and resources with each other, and online tools and resources are used to network cost-effectively. However, this review is not systematic or peer-reviewed, and it is not clear what indicators of effectiveness were used, so the results should be interpreted with caution.

- ALI provided anecdotal evidence of the effectiveness of the Aquatic Animal Alliance (AAA), such as: the sharing of knowledge and ideas between members (including providing organizations with technical resources to carry out aquatic campaigns when they lack the capacity to run their own); the ability of such an alliance to act as a formidable collective force when advocating for change; and the opportunity for such a multifaceted body to take action on many different fronts. They also highlight the AAA’s role in uniting aquatic animal advocacy organizations behind a small number of unified, evidence-backed asks. We value the work of such coalitions; for example, this ACE report highlights the benefits of groups working together to exert greater influence and stand a greater chance of success in their policy asks. This seems likely to be especially important for a nascent animal welfare movement like aquatic animal advocacy, focused on a particularly complex and fast-growing industry like aquaculture.52

- Examples of support that ALI has provided include:

- Drafting a best practice aquaculture manual for the state of Maine, to support an ongoing legal initiative led by Animal Outlook to convince the state to implement these practices.

- Supporting South African members Animal Law Reform and the Coalition of African Animal Welfare Organisations (CAAWO) to send comments for the aquaculture bill being amended in the country.

- Supporting New Zealand member Animals Aotearoa to provide comments on the country’s fisheries industry transformation plan and bill, and the national organic standards.

- In terms of member engagement, ALI reports that their pieces of feedback on policies (see Key Activity 1) are signed by on average 110–130 member organizations, out of the total approximately 145 members. To monitor and improve member engagement, they carry out an annual member survey, asking for feedback and how to improve and provide them with more value from the AAA, and report that they plan to conduct a similar survey for the Aquatic Animal Policy focus group in the future. They also hold occasional webinars that typically average 20–30 live attendees.

- ALI reports taking various measures to ensure that the AAA is effective, inclusive, and cohesive. For example, they enlist the help of member organizations in translating aquatic animal welfare reports and documents so they can be available to members who do not speak English as their first language; they established an Aquatic Animal Alliance advisory committee of six members across different geographies, demographics, and organization size that provides strategic guidance and quarterly assessments; they provide onboarding materials when new members commit to joining the alliance; they share monthly newsletters and social media highlights; and they share resources, advice, and constructive feedback to ensure members can develop their own initiatives, and are investing in a membership hub platform to help disseminate such information more effectively.

Risks, limitations, and mitigating factors

- Limitation: Sustaining engagement and commitment over time can be challenging when member organizations are operating under limited bandwidth.

- Mitigating factors: ALI seeks to foster a sense of community through webinars, newsletters, and social media highlights. They also seek to provide support in the form of resource sharing, advice, and constructive feedback to ensure members can develop their own initiatives, and they are investing in a membership hub platform to help disseminate such information more effectively. They conduct an engagement survey for their Aquatic Animal Alliance and plan to run a similar survey for the Aquatic Animal Policy focus group in the future. If they receive sufficient funding, ALI also plans to increase their coalition’s impact by hiring an AAA community manager to handle administrative tasks, resource coordination, and event organization. This would enable the current AAA director to focus more on intra-movement strategy and coordination, including geographically-specific focus groups in Africa and Asia.

- Limitation: There can be conflicts or miscommunications between member organizations due to cultural differences.

- Mitigating factors: As mentioned above, ALI enlists the help of member organizations in translating aquatic animal welfare reports and documents so they can be available to members who do not speak English as their first language. ALI has also established an Aquatic Animal Alliance advisory committee of six members across different geographies, demographics, and organization sizes that provides strategic guidance and quarterly assessments. ALI also provides onboarding materials when new members commit to joining the alliance.

Key activity assessment

Overall, taking into account the limitations and mitigating factors, we assess the logic and evidence of this key activity as moderate to strong. We positively note that:

- ALI appears to have implemented measures to ensure that the AAA is sensitively and efficiently managed.

- ALI’s coalitions appear to align closely with ALI’s other activities, particularly their policy feedback work, significantly increasing their likely impact.

- The AAA appears to have a wide, varied, and engaged membership.

Potential challenges include:

- There is very little evidence on the effectiveness of animal advocacy coalitions.

- While ALI provided us with positive testimonials from some of their members and reports that they solicit feedback from members via surveys, as an external organization we have limited insight into how useful most members find the AAA in practice.

Key Activity 4: Certifier benchmark

Activity description: ALI evaluates the existing welfare standards of aquatic animal product certifiers (such as the Aquaculture Stewardship Council,53 Friend of the Sea,54 and Best Aquaculture Practices55), most of which operate internationally and which typically certify a range of standards beyond animal welfare, such as sustainability. ALI ranks these in an annual benchmark, and engages with certifiers to persuade them to improve their standards. In practice, most of this work has benefited shrimps to date, rather than finfish.

Supportive reasoning and evidence base

- As detailed in Key Activity 1, a huge number of fishes and shrimps are farmed and slaughtered annually.

- Major aquaculture certification schemes cover a huge number of farmed fishes and shrimps. The certifiers that ALI engages with certify approximately 67.3 billion shrimps and 2.4 billion finfish per year, according to their own calculations based on certifier data. This equates to approximately 15% of the total number of farmed shrimps slaughtered per year and 2% of the total number of farmed finfish slaughtered per year.56

- In practice, most (though not all) of ALI’s recent engagement with certifiers has been to improve their welfare standards for shrimps specifically. They report that this is partly because improvements for shrimps are often easier to identify and implement given that there are only two commonly farmed species (whereas finfish encompass many species, each with specific welfare requirements); and partly because shrimp production certifiers are paying more attention to shrimps lately given the rapidly growing nature of the shrimp farming industry.

- ALI’s reasoning behind this program is that they can persuade certifiers to improve their welfare standards as a means to attract more business from retailers that have themselves made aquatic animal welfare commitments (thereby aligning with their corporate engagement work described in Key Activity 2).

- ALI reports that they plan to use various incentives to push certifiers to compete in the benchmark ranking. This is currently in its early stages, but ALI reports that this will shape their work on the benchmark over the long term. They expect high-scoring certifiers to benefit in the following ways: attracting positive public perception and media coverage, particularly in industry publications; inviting more opportunities for collaboration with NGOs; aligning with ESG criteria, which investors see as increasingly important; pre-empting future regulation and inviting more opportunities for collaboration with governments; accessing preferential access to subsidies or favorable regulatory treatment in certain regions; increasing their global credibility, including with international bodies such as the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

- ALI reports that they have scored seven certifiers using their benchmarking scheme, engaged with four certifiers to improve their welfare standards, and are aware of at least two certifiers actively using their ranking on ALI’s benchmark in their marketing with retailers. The Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) also publicized its top ranking on the benchmark.57

Risks, limitations, and mitigating factors

- Limitation: ALI cites rising consumer demand for higher-welfare aquatic animal products as a lever for retailers, and by extension, the bodies certifying the retailers’ products, to improve their aquatic animal welfare standards. As noted in Key Activity 2, there is some evidence to support consumers’ increased willingness to pay (WTP) for higher-welfare animal products, but it cannot be assumed that consumers’ hypothetical WTP will bear out in real-world settings. We are also not confident in consumers’ ability to distinguish between different certifiers, given the general public’s apparent confusion surrounding welfare labels and lack of understanding of aquatic animals’ production and welfare requirements.58

- Mitigating factors: ALI acknowledges that consumer understanding of welfare labels is limited. As such, they seek to use a ‘top-down’ approach by engaging directly with retailers and certifiers, given that their welfare improvements shape consumers’ purchases indirectly and can raise consumers’ awareness of aquatic animal welfare. They also use arguments to convince retailers and certifiers to change their welfare practices that do not solely rely on their consumers’ existing interest in higher-welfare aquatic animal products, such as the benefits of staying ahead of upcoming progressive welfare legislation and expectations around ESG standards.

- Limitation: Of the commitments ALI has helped secure with retailers so far, none specify that the retailer must adhere to the standards of higher-scoring certifiers on ALI’s benchmark.

- Mitigating factors: ALI reports that they emphasize strategic incrementalism in their efforts, as retailers may prefer an incremental approach to adopting higher welfare standards. This can start with baseline commitments (such as committing to sourcing products from any certifier, as opposed to non-certified products) and gradually improving their sourcing policies over time (such as only sourcing from the higher-ranking certifiers listed in ALI’s benchmark). ALI reports that they support this approach by providing a clear roadmap for improvement, including intermediate milestones and recognition for incremental progress. This helps retailers build confidence and capacity to fully commit to ALI’s benchmark standards. ALI also reports that they plan to work more with retailers to map their supply chains and develop phased transition plans that gradually increase the proportion of products from high-ranking certifiers without disrupting their operations.

- Limitation: While a very high ranking on ALI’s benchmark can be beneficial for certifiers, there are currently no negative implications for certifiers with low rankings. This is particularly the case given consumers’ lack of understanding of different aquaculture certification schemes, making certification an area ripe for humanewashing and greenwashing.

- Mitigating factors: ALI’s benchmark includes annual evaluations with the rankings and specific performance metrics of all certifiers. They publicly highlight high performers and those with significant room for improvement in their annual certifier recommendations report. They are also exploring the future inclusion of a benchmark commitment that penalizes certifiers for not improving their welfare standards over time. Overall, though, ALI reports that they have deliberately avoided “shaming” low-scoring certifiers in an effort to encourage incremental progress. In general, ALI points to animal welfare having become a key theme of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards in recent years.59 They believe this will have a significant influence on certifiers; for example, the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) has stated that farmed aquatic animal welfare is playing an increasing role in perceptions of responsible production.60 ALI also highlights that certifiers have come under increased scrutiny over the past few years due to increased media exposure of animal welfare concerns surrounding their operations.

- Risk: Certification schemes can be expensive and technically demanding for producers, meaning that the largest producers (which are typically highly intensive) are the most likely to obtain certification.61 Therefore, encouraging greater rates of certification could help to strengthen large, intensive producers’ hold on the aquaculture industry.

- Mitigating factors: Certification schemes can also bring additional support to small and medium-sized farms. Globally, a significant majority of farmed seafood comes from small- and medium-sized producers, and industry efforts are being made to increase access to certification. For example, more than 1,000 small-scale farms have already earned Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) certification for responsibly farmed seafood as a result of ASC’s group certification.62 ASC also offers an Improver Programme designed to support farms that want to improve their practices but cannot currently achieve certification or do not wish to seek certification.63

- Limitation: Encouraging certification may be less promising in Asia, where most aquatic animals are farmed and consumed, as evidence suggests that sustainable practices and ecolabels exert relatively little influence on Asian consumer behavior compared to other factors.64

- Mitigating factors: While ALI acknowledges their relative lack of experience working in Asia, they report that they currently aim to support local organizations there through the AAA. They also note that certifiers in any region are likely to certify aquatic animal products in multiple other regions, yielding potential welfare improvements in those regions.

- Limitation: The quality and availability of data across certification schemes can be inconsistent, which can lead to inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the benchmark.

- Mitigating factors: ALI prioritizes using public information to evaluate certification standard. However, this information is not always readily available and can be outdated. In an attempt to evaluate only the most updated certification standards, in 2023, ALI allowed certifiers to share upcoming farming standard drafts with them to be included in the benchmark.

- Limitation: Neither ACE nor ALI are aware of evidence on the rate of compliance of producers covered by aquaculture certification schemes.

- Mitigating factors: Even if the rate of compliance is relatively low, the number of animals affected is still likely to be very high, given the sheer number covered by certification schemes.

Key activity assessment

Overall, taking into account the limitations and mitigating factors, we assess the logic and evidence of this key activity as moderate. We positively note that:

- ALI appears to have had some productive engagement with certifiers that have contributed to some helpful amendments to the certification welfare standards that could be built on in the future, and the certifiers’ widespread coverage could lead to a huge number of animals’ lives being improved.

- There appears to be strong potential for this program to align effectively with their Corporate Engagement program.

Potential challenges include:

- This program largely relies on certifiers being able to use their high scores on ALI’s benchmark to attract business from major retailers. However, retailer commitments to date have not included a commitment to only purchase from certifiers that score higher on ALI’s benchmark (though ALI does state that they encourage retailers to do so and plan to emphasize this more in the future).

- As with ALI’s corporate outreach work, we are uncertain about consumers’ engagement with higher-welfare aquatic animal products, which seems like an important part of the theory of change for getting retailers to improve their standards, even if ALI also uses other arguments to persuade retailers to do so.

Additional Considerations

- ALI provided clear, detailed information about the nature of their programs and their track record to date, supplemented by some evidence from reliable external sources supporting their choice of approach. They provided some examples of limitations to their work upfront and readily engaged with us on the other limitations that we raised.

- ALI expresses a strong commitment to Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL). Examples of this to date include speaking to experts to inform their policy asks, carrying out a basic impact assessment of their certification work, and sharing a feedback survey with members of the AAA. We positively note that they plan to hire a specialist to develop their MEL further in the future; in our view, the priorities for such a specialist should be to monitor the likely contributions of their policy work and to produce a more nuanced impact assessment for their certification work (as their current certifier impact assessment, while informative, is fairly simple and appears overly optimistic).65

- One overarching source of uncertainty is the relative lack of evidence on the probability of sentience of shrimps. (This is due to the overall lack of research on this topic rather than because of any evidence that shrimps lack sentience.) The best source of evidence we have read on this point is Rethink Priorities’ Welfare Range Estimates, which indicate (with high uncertainty) that shrimps’ “welfare ranges” (i.e., the differences in the possible intensities of their pleasures and pains) are plausibly very similar to those of carp and salmon, and roughly within an order of magnitude of those of pigs and chickens.66 We view this, combined with the vast number that are farmed and slaughtered, as sufficient justification to work to improve their welfare.67

- Throughout our evaluation, we made attempts to independently verify the information we received from ALI, especially when assessing cruxes and assumptions in the logic of their theory of change. For example, we consulted experts on the extent of ALI’s involvement in political outreach at the E.U. level. All of the information was either fully or partially verified to the extent that we trust ALI was sufficiently transparent with us.

See ALI’s cost-effectiveness spreadsheet for a detailed account of the data and calculations that went into our cost-effectiveness analysis.

We focused our analysis on two programs: (i) Corporate and institutional outreach and certifier engagement and (ii) policy feedback. Focusing on these two programs allows us to understand most of ALI’s work. These two programs are also more easily quantifiable based on the number of animals impacted and the number of policy engagements. In this case, we combined the corporate and institutional outreach to retailers and certifiers into one program because they both result in welfare improvements in the aquaculture industry. We also included ALI’s alliance work expenses in the cost-effectiveness calculations for the two other programs. According to ALI, their alliance work mostly contributes to their corporate and institutional outreach and certifier engagement and policy feedback programs. The alliance work expenditures were split equally between these programs. This means that our cost-effectiveness analysis covers 92% of ALI’s programmatic expenditures.

Program 1: Corporate and institutional outreach

- Through the seven commitments ALI secured in 2023, they managed to avert approximately 500 (lower bound: 20, upper bound: 2,300) Suffering-Adjusted Days (SADs) 68 per dollar through various retailers committing to implementing shrimp stunning. This equals approximately 4,948 (lower bound: 200, lower bound: 23,501.7) shrimps receiving electrical stunning per dollar. Besides that, the commitments also led to approximately 900k (lower bound: 0, lower bound: 3.8M) shrimps per dollar receiving environmental enrichments during their lifespan.

- According to AIM’s benchmark, a program with fewer than 10 SADs averted per dollar has low cost-effectiveness, 10–30 SADs averted per dollar has moderate cost-effectiveness, 30–100 SADs averted per dollar has moderate-to-high cost-effectiveness, and greater than 100 SADs averted per dollar has very high cost-effectiveness.

- There are several limitations to our cost-effectiveness estimate. We were only able to include the electrical stunning of shrimp as a quantified welfare improvement despite ALI working on several other changes, such as environmental enrichment for shrimps and finfishes. This is because of a lack of existing scientific evidence about the impact of these welfare improvements on animals and the details about specific implementation of these. We expect these improvements would add to the quantified impact. Our estimate is further limited by the lack of clearer scientific evidence surrounding shrimp sentience and the uncertainty around the expected length of impact of the welfare improvements. This year might also not be fully representative of this program, as this program was only launched in March 2023.

Program 2: Policy feedback for farmed fishes and wild-caught fishes

- Through their work in 2023 and with the support of their Aquatic Animal Alliance, ALI was able to provide feedback and consult on policies, sign letters, and engage with various policy stakeholders on 30 occasions. ALI was able to conduct approximately one policy engagement for every $10,000 spent on this program. This equals 0.0001 policy engagements per dollar.

- ALI’s policy engagements in 2023 include presenting at conferences, providing feedback for policies, providing guidance, sending letters, etc. ALI engages with national governments, international organizations (such as the E.U., U.N., and FAO), and more.

- For ALI’s policy feedback work, we were unable to estimate the Suffering Adjusted Days (SADs) per dollar and stopped at estimating the average cost of a policy engagement. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, the policy engagements ALI worked on in 2023 are mostly still several years away from their potential implementation; therefore, it is hard to estimate whether they will be implemented and what impact they will bring. Secondly, the nature of ALI’s policy work is that they provide feedback globally and whenever they see an opportunity. It is likely that some of these engagements will result in a high impact, while others will have little or no impact. Thirdly, it is hard to trace the exact impact an implemented policy has on the number of animals and the exact way their lives were improved.

- Due to the limited data and empirical evidence, this cost-effectiveness analysis did not play a meaningful role in our recommendation decision for ALI.

Room For More Funding

How much additional money can ALI effectively use in the next two years?

With this criterion, we investigate whether ALI would be able to absorb the funding that a new recommendation from ACE may bring. We also investigate the extent to which we believe that their future uses of funding will be as effective as their past work. All descriptive data and estimations for this criterion can be found in the Financials and Future Plans spreadsheet. For more detailed information on our 2024 evaluation methods, please visit our Evaluation Criteria web page.

Our Assessment of ALI’s Room For More Funding

Based on our assessment of their future plans, we believe that ALI could effectively use revenue of up to roughly $1.2M annually in 2025 and 2026, and their annual room for more funding is roughly $0.4M. With additional funding, they would prioritize hiring a full-time Development Officer to lead their fundraising, a full-time Certifier Specialist for their certifier outreach work, and an Aquatic Animal Alliance (AAA) Community Manager. Overall, we expect these plans will be similarly effective to ALI’s past work.

To support Aquatic Life Institute, and all of ACE’s current Recommended Charities, please consider donating to our Recommended Charity Fund.

If ALI were to find additional revenue to expand their organization, they would prioritize using the money to hire additional staff. This would include, among other roles, a full-time development officer to lead their fundraising, a full-time certifier specialist for their certifier outreach work, and an Aquatic Animal Alliance (AAA) community manager. We found their plans to hire an AAA community manager particularly promising, given that it would facilitate the effective running of the coalition and also free up the current AAA Director to focus more on intra-movement strategy and coordination. We have confidence that these uses of funding will be as effective as their past work up to a total annual revenue level of roughly $1.2M, which we refer to as their funding capacity.

The chart below shows ALI’s revenues from 2021–2023, their projected revenue for 2024, and their funding capacity for 2025 and 2026.

A more detailed summary of their future plans and the reasoning behind our assessments can be found in the “Future Plans” tab of their Financials and Future Plans spreadsheet.

Organizational Health

Are there any management issues substantial enough to affect ALI’s effectiveness and stability?

With this criterion, we assess whether any aspects of ALI’s governance or work environment pose a risk to its effectiveness or stability, thereby reducing its potential to help animals. Bad actors and toxic practices may also negatively affect the reputation of the broader animal advocacy movement, which is highly relevant for a growing social movement, as well as advocates’ wellbeing and willingness to remain in the movement.69 For more detailed information on our 2024 evaluation methods, please visit our Evaluation Criteria web page.

Our Assessment of ALI’s Organizational Health

We did not detect any concerns in Aquatic Life Institute’s leadership and organizational health. We positively note that they have a solid process in place to evaluate leadership performance, an independent board that meets regularly, and they are proactive about organizational health. In the staff engagement survey, employees positively noted Aquatic Life Institute’s inclusive, supportive, and empowering work culture and the strong sense of respect, collaboration, and encouragement to achieve work-life balance. Staff also noted that leadership is genuine and approachable.

People, Policies, and Processes

The policies that the charity reported having in place are listed below.70

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| COMPENSATION | |

| Paid time off | |

| Paid sick days | |

| Paid medical leave | |

| Paid family and caregiver leave | |

| Compensation strategy (i.e., a policy detailing how an organization determines staff’s pay and benefits in a standardized manner) | |

| WORKPLACE SAFETY | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances | |

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics or conduct | |

| A written statement that the organization does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other irrelevant characteristics | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels, up to and including the board of directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| Documentation of all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Conflict of interest policy | |

| Training on topics of harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| CLARITY, TRANSPARENCY, AND BIAS MITIGATION | |

| Clearly defined responsibilities for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| Clear organizational goals and/or priorities communicated to all employees | |

| New hire onboarding or orientation process | |

| Structured hiring, assessing all candidates using the same process | |

| Standardized process for employment termination decisions | |

| Process to evaluate leadership performance | |

| Performance evaluation process based on predefined objectives and expectations | |

| Two or more decision-makers for all hiring, promotion, and termination decisions | |

| Process to attract a diverse candidate pool | |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STABILITY AND PROGRESS | |

| Documentation of all key knowledge and information necessary to fulfill the needs of the organization | |

| Board meeting minutes | |

| Records retention and destruction policy | |

| Systems in place for continuously learning from the past (e.g., feedback norms, retrospectives) | |

| Recurring (e.g., weekly or every two weeks) 1-on-1s focused on alignment and development | |

| ASSESSMENTS | |

| Annual (or more frequent) performance evaluations for all paid roles | |

| Annual (or more frequent) process to measure employee engagement or satisfaction | |

| A process in place to support performance improvement in instances of underperformance | |

Transparency

ALI was transparent with ACE throughout the evaluation process.

All of the information we required for our evaluation of organizational health is made available on ALI’s website. This includes: a list of board members; a list of key staff members; information about the organization’s key accomplishments; the organization’s mission, vision, and theory of change; a privacy policy disclosing how the organization collects, uses, and shares third-party information; and financial statements.

ALI is also transparent with both the public and their staff. For example, all policies are shared with staff.

Leadership and Board Governance

- Managing Director: Sophika Kostyniuk, has been involved in the organization for almost three years.

- Number of board members: five members.

We found that the charity’s board fully aligned with our understanding of best practices. All five board members are independent from the organization and board meetings take place at least four times per year.

One hundred percent of staff respondents to our engagement survey agree they have confidence in ALI’s leadership team.

ALI is based in the U.S. and has a subsidiary in France to facilitate work within the E.U.

Financial Health

Reserves

With only about 45% of their current annual expenditures held in net assets (as reported by ALI for 2024), we believe that they could benefit from prioritizing having a larger amount of reserves. This would provide them with financial stability during periods of unexpected income shortfalls or sudden increases in expenses, allowing them to continue their operations and programs without interruption.

Recurring Revenue

67% of ALI’s revenue is recurring (e.g., from recurring donors or ongoing long term grant commitments).71

Liabilities to Assets Ratio

ALI’s liabilities-to-assets ratio did not exceed 50% or pose a risk to operations at the time of assessment.

Staff engagement and satisfaction

ALI has 9 staff members (full-time, part-time, and contractors), including the Managing Director. 8 staff members responded to our staff engagement survey, yielding a response rate of 100%—the Managing Director was asked not to take the survey.

ALI has a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. Of the staff that responded to our survey, about all report that they are satisfied with their wage. ALI offers paid vacation and sick days, and healthcare coverage. All staff report that they are satisfied with the benefits provided. This suggests that, on average, staff exhibit very high satisfaction with wages and benefits.

The average score among our staff engagement survey questions was 4.9 (on a 1–5 scale), suggesting that, on average, staff exhibit very high engagement.

Harassment and Discrimination

ACE has a process separate from the engagement survey for receiving serious claims about harassment and discrimination, and all ALI staff were made aware of this option. If staff or any party external to the organization have claims of this nature they are encouraged to read ACE’s Third-Party Whistleblower Policy and fill out our claimant form. We have received no such claims regarding ALI.

To view all of the sources cited in this review, see the reference list.

Ritchie et al. (2023). Our World in Data bases their analyses on data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

For our cost-effectiveness assessments we aimed to use Ambitious Impact’s new internal system of estimating Suffering-Adjusted Days (SADs) for making quantitative decisions on animal welfare ideas. SADs roughly represent the number of days of intense pain felt by each animal. They are essentially a measure of days in pain with various adjustments for the intensity of pain, sentience, and welfare range (i.e., their relative capacity to experience pain and pleasure, in accordance with Rethink Priorities’ Welfare Ranges report). SADs are adjusted to “disabling” levels of pain on the Welfare Footprint pain scale. So one day spent in disabling pain for one human would be equal to one SAD. A program with fewer than 10 SADs averted per dollar has low cost-effectiveness, 10–30 SADs averted per dollar has moderate cost-effectiveness, 30–100 SADs averted per dollar has moderate-high cost-effectiveness, and greater than 100 SADs averted per dollar has a very high cost-effectiveness.

AIM considers 10–30 SADs averted per dollar to be their bar for a cost-effective intervention.

Open Philanthropy (2016). Note that farmed fish numbers are based on 2016 data, so they are likely to be an underestimate.

See for example Tallberg et al. (2015) on the importance of multiple NGOs lobbying as part of a cohesive network.

Bryant et al. (2023); for an example of the voter-buyer gap in the E.U., see European Commission (2023)

For examples of media coverage of this ban citing ALI’s contributions, see CIWF (2024); The Fish Site (2024).

See for example Ryba (2022), which recommends using expert judgment and superforecaster panels to evaluate the counterfactual impact of lobbying in animal advocacy.

For an example of such a policy assessment, see Bridgwater (2023).

Waldhorn & Autric (2023; Pegg (2019), cited in Thakrar (2024). Our estimate is based on data indicating that 10.8 million tonnes of farmed and wild-caught shrimps are slaughtered globally each year, equating to around 25 trillion shrimps, of which 40,000 tonnes are consumed by U.K. retail customers.

See for example Harris et al. (2022), Anderson & Lenton (2019), and Sentience Institute (2020).

See for example Andreyeva et al. (2010), Font-i-Furnols (2023), and Sentience Institute (2020).

For evidence supporting consumers’ increased WTP, see for example Gorton et al. (2023), or Shrimp Welfare Project (2023), which specifically explores WTP for high-welfare shrimp.

For example, see Farm Forward (2021).

For example, based on focus group research, The Humane League (2021) indicates there is little awareness of, or interest in, fish labeling and certification schemes.

FMI (2023), cited in Goldschmidt (2023)

For example, see The World Bank (2024).

See ALI’s insect farming work, octopus farming work, and plant-based fish feed work.

For example, see Richard et al. (2023) for Walmart’s pledge.

For example, see Balzani & Hanlon (2020)

See for example Scott-Reid (2024) on humanewashing in the aquaculture industry.

See Farms Initiative (n.d.) for some examples.

For example: Schyns & Schilling (2013) report that poor leadership practices result in counterproductive employee behavior, stress, negative attitudes toward the entire company, lower job satisfaction, and higher intention to quit. Waldman et al. (2012) report that effective leadership predicts lower turnover and reduced intention to quit. Wang (2021) reports that organizational commitment among nonprofit employees is positively related to engaged leadership, community engagement effort, the degree of formalization in daily operations, and perceived intangible support for employees. Gorski et al. (2018) report that all of the activists they interviewed attributed their burnout in part to negative organizational and movement cultures, including a culture of martyrdom, exhaustion/overwork, the taboo of discussing burnout, and financial strain. A meta-analysis by Harter et al. (2002) indicates that employee satisfaction and engagement are correlated with reduced employee turnover and accidents and increased customer satisfaction, productivity, and profit.

Policies in bold text in the table are those that Scarlet Spark recommends as highest priority.

Based on an external consultation with Scarlet Spark, an organizational consultant for animal nonprofit groups, we find this to be a high proportion of recurring revenue (the ideal being 25% or higher); however, the 25% target is dependent on the context for each charity, so while we have noted this information here, it did not influence our recommendation decision.

ALI’s Achievements

- ALI helped achieve a statewide ban on octopus farming and the import of farmed octopuses in California, following a March 2024 victory in Washington state.

- ALI played a pivotal role in the development of seafood brand BlueYou’s first-of-its-kind Animal Welfare Policy, which covers both farmed and wild aquatic animal sourcing.

- Leaning on ALI’s expertise, Hilton Foods produced its first crustacean welfare policy. Crustaceans are now acknowledged as sentient beings and their welfare implications during farming, transport, and slaughter are taken into account.

Future Outlook

With your help, ALI will be able to elevate global aquatic animal welfare standards by advocating for the adoption of high-welfare recommendations among leading seafood certification bodies. They will work toward influencing international and local policy, shaping corporate commitments for large-scale impact, building unified global coalitions, and continuing the fight against the developing octopus farming industry.