Coalition of African Animal Welfare Organisations

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2021 |

Archived Version: November, 2021

What does CAAWO do?

Coalition of African Animal Welfare Organisations (CAAWO) develops their programs in South Africa and conducts some of their work in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Kenya, and Egypt. Their work focuses on improving animal welfare standards, and to a lesser extent, also aims to increase the prevalence of anti-speciesist values and strengthen the animal advocacy movement. They campaign for legislative changes, carry out research in animal law and industrial agriculture, and raise awareness of animal-related issues through education and social media.

What are their strengths?

We believe that CAAWO’s programs focusing on farmed animal welfare, especially their work targeting numerous and neglected animal groups such as chickens and fishes, can be impactful. We consider their work in South Africa to be particularly effective due to the high number of animals, low number of similar organizations, and high tractability of farmed animal advocacy in the country. They have significant plans for expansion, and we believe that they would be able to effectively absorb an increase in funding.

What are their weaknesses?

Many of CAAWO’s programs began in 2020 and 2021. Therefore, their short track record makes the impact of their work difficult to assess. CAAWO is a small organization, and we believe they could benefit from developing staff policies to ensure a safe and positive work culture as they expand.

Programs

A charity that performs well on this criterion has programs that we expect are highly effective in reducing the suffering of animals. The key aspects that ACE considers when examining a charity’s programs are reviewed in detail below.

Method

In this criterion, we assess the effectiveness of each of the charity’s programs by analyzing (i) the interventions each program uses, (ii) the outcomes those interventions work toward, (iii) the countries in which the program takes place, and (iv) the groups of animals the program affects. We use information supplied by the charity to provide a more detailed analysis of each of these four factors. Our assessment of each intervention is informed by our research briefs and other relevant research.

At the beginning of our evaluation process, we select charities that we believe have the most effective programs. This year, we considered a comprehensive list of animal advocacy charities that focus on improving the lives of farmed or wild animals. We selected farmed animal charities based on the outcomes they work toward, the regions they work in, and the specific animal group(s) their programs target. We don’t currently consider animal group(s) targeted as part of our evaluation for wild animal charities, as the number of charities working on the welfare of wild animals is very small.

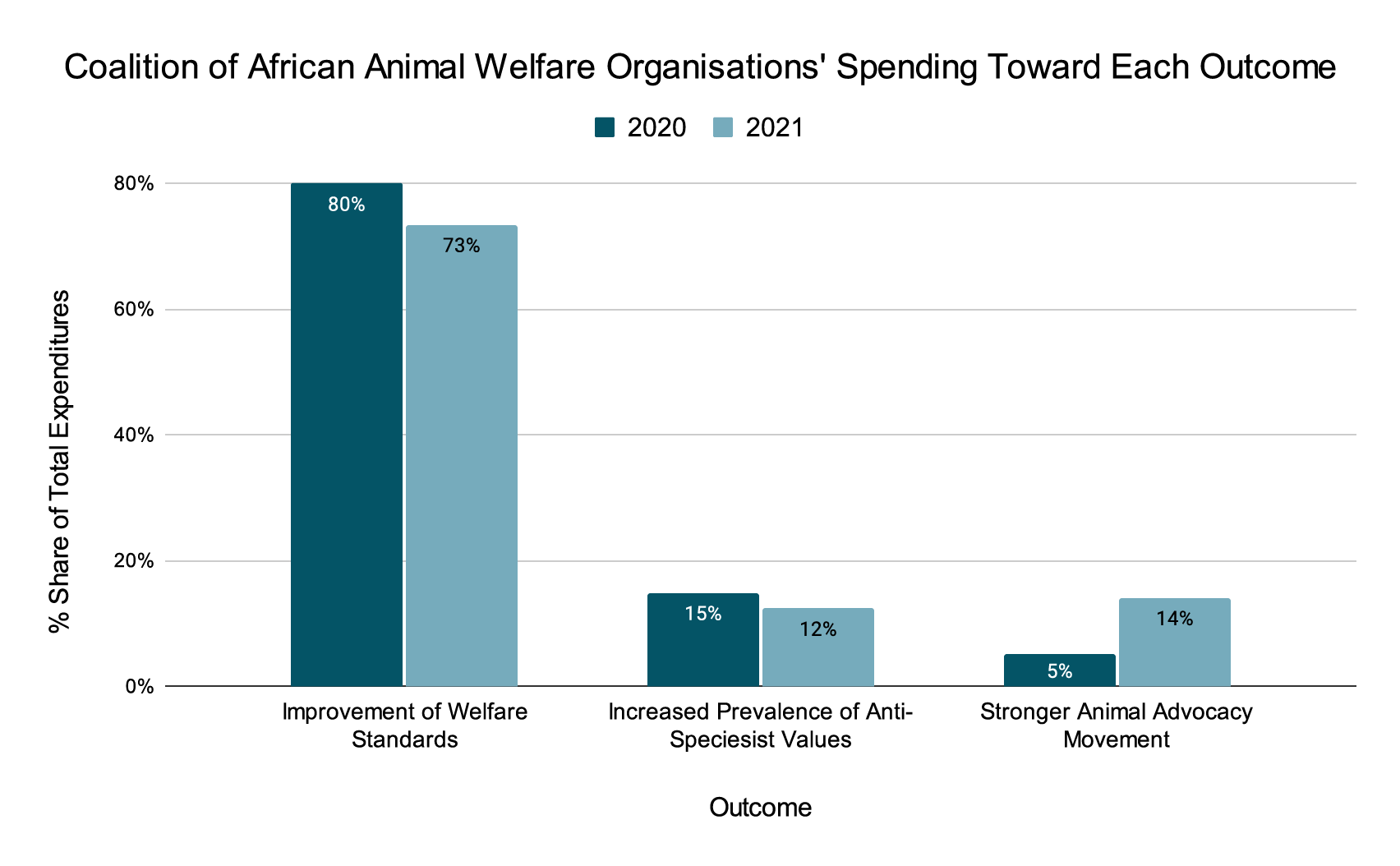

Outcomes

We categorize the work of animal advocacy charities by their outcomes, broadly distinguishing whether interventions focus on individual or institutional change. Individual-focused interventions often involve decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Institutional change involves improving animal welfare standards, increasing the availability of animal-free products, or strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

We believe that changing individual habits and beliefs is difficult to achieve through individual outreach. Currently, we find the arguments for an institution-focused approach1 more compelling than individual-focused approaches. We believe that raising welfare standards increases animal welfare for a large number of animals in the short term2 and may contribute to transforming markets in the long run.3 Increasing the availability of animal-free foods, e.g., by bringing new, affordable products to the market or providing more plant-based menu options, can provide a convenient opportunity for people to choose more plant-based options. Moreover, we believe that efforts to strengthen the animal advocacy movement, e.g., by improving organizational effectiveness and building alliances, can support all other outcomes and may be relatively neglected.

Therefore, when considering charities to evaluate, we prioritize those that work to improve welfare standards, increase the availability of animal-free products, or strengthen the animal advocacy movement. We give lower priority to charities that focus on decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Charities selected for evaluation are sent a request for more in-depth information about their programs and the specific interventions they use. We then present and assess each of the charities’ programs. In line with our commitment to following empirical evidence and logical reasoning, we use existing research to inform our assessments and explain our thinking about the effectiveness of different interventions.

Countries

A charity’s countries and regions of operations can affect their work with regard to scale, neglectedness, and tractability. We prioritize charities in countries with relatively large animal agricultural industries, few other charities engaged in similar work, and in which animal advocacy is likely to be feasible and have a lasting impact. In our charity selection process, we used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI), which combines proxies for scale, tractability, and global influence to create country scores.4 To assess neglectedness, we used our own data on the number of organizations that we are aware of working in each country. Below we present these measures for the countries that CAAWO operates in.

Animal groups

We prioritize programs targeting specific groups of animals that are affected in large numbers5 and receive relatively little attention in animal advocacy. Of the 187 billion farmed vertebrate animals killed annually for food globally, 110 billion are farmed fishes and 66.6 billion are farmed chickens, making these impactful groups to focus on. There are at least 100 times as many wild vertebrates as there are farmed vertebrates.6 Given the large number of wild animals and the small number of organizations working on their welfare, we believe wild animal advocacy also has potential for high impact despite its lower tractability.

A note about long-term impact

Each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.7 The potential number of animals affected increases over time due to population growth and an accumulation of generations. Thus, we would expect that the long-term impacts of an action would likely affect more animals than the short-term impacts of the same action. Nevertheless, we are highly uncertain about the particular long-term effects of each intervention. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew toward overemphasizing short-term effects.

Information and Analysis

Cause areas

CAAWO’s programs focus primarily on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we think is a high-priority cause area.

Countries

CAAWO develops their programs in South Africa and has no subsidiaries in other countries. However, some of their current programs target other countries, including Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Kenya, and Egypt.

We used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI) with the suggested weightings of scale (25%), tractability, (55%) and influence (20%) to determine each country’s total FAOI score. We report this score along with the country’s global ranking from a total of 60 countries in the following format: FAOI score(global ranking). South Africa has the following score and ranking: 15.52(24). The FAOI does not include Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Kenya, or Egypt. According to the comprehensive list of charities we are aware of, there are about 724 farmed animal advocacy organizations, excluding sanctuaries, worldwide. From this list, we found 6 in South Africa, 6 in Tanzania, 1 in Zimbabwe, 1 in Rwanda, 4 in Kenya, and 0 in Egypt. We believe that farmed animal advocacy in South Africa is relatively tractable and neglected. We also believe that advocacy in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Kenya, and Egypt could be high-impact due to the neglectedness of farmed animal advocacy work in those areas, but there is not enough information for us to be highly confident about this.

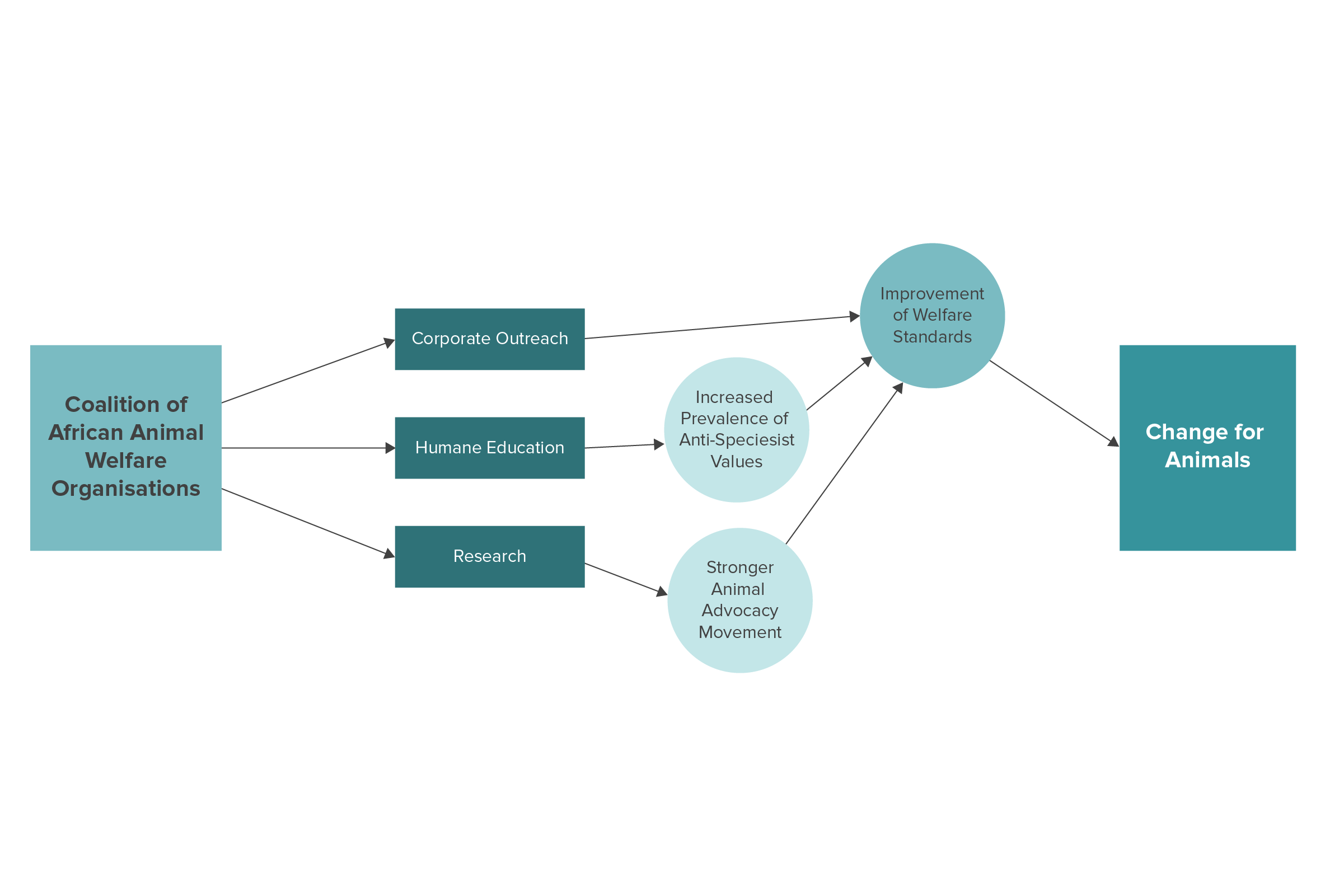

Description of programs

CAAWO pursues different avenues for creating change for animals. Their work focuses on improving animal welfare standards, and to a lesser extent, also aims to increase the prevalence of anti-speciesist values and strengthen the animal advocacy movement.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

Below, we describe each of CAAWO’s programs, listed in order of the financial resources devoted to them in 2020 (from highest to lowest). We list major accomplishments for each program, if a track record is available.

CAAWO’s programs

This program focuses on creating changes in policies to ban battery cages for chickens in southern Africa—specifically in South Africa, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and recently, Rwanda.

Main interventions

- Government outreach

- Corporate outreach (corporations, retailers, producers)

- Outreach to consumers

This program focuses on creating changes in policies to ban sow stalls for pigs in southern Africa—specifically in South Africa, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and recently, Rwanda.

Main interventions

- Government outreach

- Corporate outreach (corporations, retailers, producers)

- Outreach to consumers

This program focuses on raising awareness of welfare issues of companion, farmed, and wild animals. In particular, this program aims to incorporate humane education into the curriculum of schools in South Africa.

Main interventions

- Humane education

Key historical accomplishments

Main interventions

- Law and policy research

- Advice on policy

This program focuses on conducting research on the impact of industrial animal agriculture on the environment, socio-economy, and animals in Africa.

Main interventions

- Research

Research for intervention effectiveness

Legal work

CAAWO works on legal and legislative advocacy. We are not confident about the effectiveness of legal outreach because there is currently a lack of research on this topic. However, we suspect that the effects of legal change could be particularly long-lasting, despite the long time frame compared to other forms of change. We also think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to have an impact on a large number of animals.

We believe that the enforcement of animal welfare laws is important because without enforcement, there will not be a positive real-world effect on animals. There is currently a lack of research regarding the effectiveness of legal enforcement on the welfare of animals. However, there is preliminary evidence of a potential discrepancy between animal welfare laws in theory and in practice: the “enforcement gap”.8 There are many factors that could cause this discrepancy, including i) a lack of reporting of animal cruelty acts, ii) ambiguous language in animal welfare legislation, and iii) the realities of enforcement.

Corporate outreach

There is some evidence that corporate outreach leads food companies to change their practices related to hen welfare. Šimčikas9 found that the follow-through rate of cage-free corporate commitments ranges from 48–84%. Cost-effectiveness estimates vary widely, and it is unclear which is the most accurate. Šimčikas estimates that corporate campaigns affect nine to 120 hen-years (i.e., years of chicken life) per dollar spent.

CAAWO currently prioritizes cage-free egg and pig welfare commitments.10 Cage-free housing systems are believed to reduce suffering by increasing the space available to egg-laying hens and providing them opportunities to perform important behaviors, although mortality may increase during the transition process, and there is some risk that it may remain elevated.11 Gestation crates for pregnant pigs are linked to physical, mental, and behavioral issues.12 Alternative housing systems include turn-around stalls, free-range systems, pasture-based systems, and indoor group housing. There are different positive and negative factors associated with these alternatives, but all of them seem to be higher-welfare than gestation crates.

Veg outreach

There is mixed evidence on the effectiveness of humane education on changing diet patterns in individuals.

According to a recent two-year study,13 distributing animal advocacy pamphlets to individuals was associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in animal product consumption for a small subset of the sample: those who identified as vegetarian, those who thought more about animal welfare, and those who said they were willing to change their diet. However, this effect on diet only lasted for two months—the leafleting intervention did not have any statistically significant effects over the course of the entire study. Between this study and ACE’s 2017 meta-analysis about leafleting, we are uncertain about the effectiveness of individual outreach methods, such as distributing information pamphlets

Some empirical studies suggest that providing people with written information may increase their intention to consume less meat.14 However, it is uncertain how written information may affect attitudes toward animal products other than meat, how the format and specific content of the message may affect the impact on intentions, and whether changes in intentions translate into changes in consumer behavior. There is some evidence of a weak negative correlation between media coverage of animal welfare and meat demand.15 However, there is likely to be a large variation in the reach of these interventions, and it is uncertain whether they causally contribute to reducing the consumption of animal products.

Conducting animal advocacy research

We believe that conducting and supporting advocacy research is a generally promising intervention, especially when considering its potential effects in the longer term (defined as more than one year). Due to the lack of research about the extent to which animal advocacy research results are actually used by the movement to prioritize and implement their work, our confidence in the short-term effects of this intervention is low. We acknowledge that we may be generally biased to favor this intervention because part of our work consists of conducting and supporting relevant research—see our assessment of the effects of producing advocacy research.

Our Assessment

We think that CAAWO’s corporate outreach program, aimed at improving farmed animal welfare standards, seems more effective than their other programs. There is some evidence to support this claim. Additionally, we think that the program’s focus on helping farmed chickens increases its effectiveness. Since all CAAWO’s current programs commenced after 2020, however, their track record is relatively short.

We consider CAAWO’s work in South Africa to be particularly effective based on the high number of animals, low number of other organizations, and high tractability of farmed animal advocacy in the country.

Overall, we think that most of CAAWO’s spending on programs goes toward outcomes, countries, and helping species that we think are a high priority.

Room For More Funding

A new recommendation from ACE could lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding. In this criterion, we investigate whether a charity is able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in or, if the charity has a prior recommendation status, whether they will continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation.

Method

In the following section, we inspect the charity’s plans for expansion as well as their financials, including revenue and expenditure projections.

The charities we evaluate typically receive revenue from a variety of different sources, such as individual donations or grants from foundations.16 In order to guarantee that a charity will raise the funds needed for their operations, they should be able to predict changes in future revenue. To estimate charities’ room for more funding, we request records of their revenue since 2019 and ask what they predict their revenue will be in 2021–2023. A review of the literature on nonprofit finance suggests that revenue diversity may be positively associated with revenue predictability if the sources of income are largely uncorrelated.17 However, a few sources of large donations—if stable and reliable—may also be associated with high performance and growth. Therefore, in this criterion, we also indicate the charities’ major sources of income.

We present the charities’ reported plans for expansion of each program as well as other planned changes for the next two years. We do not make active suggestions for additional plans. However, we ask charities to indicate how they would spend additional funding that we expect would come in as a result of a new recommendation from ACE, considering that a Standout Charity status and a Top Charity status would likely lead to a $100,000 or $1,000,000 increase in funding, respectively. Note that we list the expenditures for planned non-program expenses but do not make any assessment of the charity’s overhead costs in this criterion, given that there is no evidence that the total share of overhead costs is negatively related to overall effectiveness.18 However, we do consider relative overhead costs per program in our Cost Effectiveness criterion. Here we focus on evaluating whether additional resources are likely to be used for effective programs or other beneficial changes in the organization. The latter may include investments into infrastructure and efforts to retain staff, both of which we think are important for sustainable growth.

It is common practice for charities to hold more funds than needed for their current expenses (i.e., reserves) in order to be able to withstand changes in the business cycle or other external shocks that may affect their incoming revenue. Such additional funds can also serve as investments into future projects in the long run. Thus, it can be effective to provide a charity with additional funds to secure the stability of the organization or provide funding for larger, future projects. We do not prescribe a certain share of reserves, but we suggest that charities hold reserves equal to at least one year of expenditures, and we increase a charity’s room for more funding if their reserves in 2021 are less than 100% of their projected total expenditure.

Finally, we aggregate the financial information and the charity’s plans to form an assessment of their room for more funding. All descriptive data and estimations can be found in this sheet. Our assessment of a charity’s ability to effectively absorb additional funding helps inform our recommendation decision.

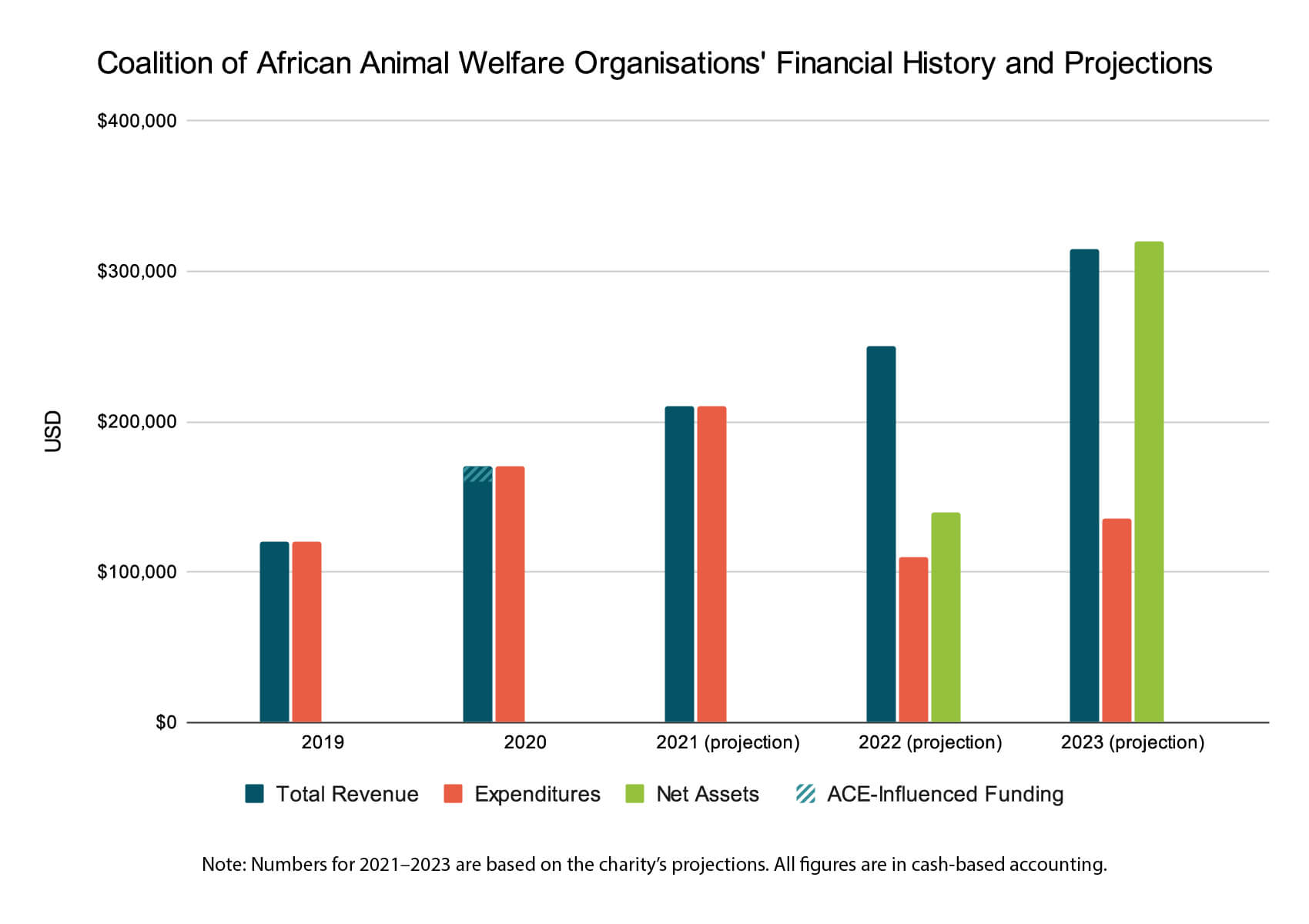

Information and Analysis

The chart below shows CAAWO’s revenues, expenditures, and net assets from 2019–2020, as well as projections for the years 2021–2023. The information is based on the charity’s past financial data and their own predictions for the years 2021–2023.

CAAWO receives all of their income from donations.19 In 2020, they received part of their funding from donations larger than 20% of their annual revenue.20

Revenue, Expenditures, Total Assets (Assets and Liabilities), ACE-Influenced Funding Over the Years 2019–2023

According to CAAWO’s reported projections, their estimated increase in revenue in 2022 will sufficiently cover their plans for expansion.

CAAWO outlined that if they were to receive an additional $100,000 per year, it would be focused on expanding their programs and hiring specific new staff members, which we believe is an effective use of funding. Therefore, we believe that CAAWO could effectively absorb at least an additional $100,000 per year.

CAAWO outlined that if they were to receive an additional $1,000,000 per year, it would be focused on opening new country offices, investing in equipment, and starting an academic research program. Setting up new offices takes time and resources from the rest of the team. In addition, it may take time to adjust an organization’s structure to a larger team. Therefore, we believe there is a limit on how fast an organization is able to grow sustainably. As CAAWO’s 2021 expenditures were $210,000,21 we believe that CAAWO could not effectively absorb an additional $1,000,000 per year.

With no current assets—as reported by CAAWO for 2021—we believe that they could benefit from holding a larger amount of reserves. As such, we add additional funding to replenish their reserves to the charity’s plans for expansion.

Below we list CAAWO’s plans for expansion for each program as well as other planned expenditures, such as administrative costs, wages, and training. We do not verify the feasibility of the plans or the specifics of how changes in expenditure will cover planned expansions. Reported changes in expenditure are based on the charity’s own estimates of changes in program expenditures for 2021–2022 and 2022–2023.

CAAWO plans to expand their following programs: cage-free campaign, sow stall free campaign, humane education, legal research, and industrial agriculture research. In addition, they look to hire staff and potentially start a program to ban live export. More details can be found in the corresponding estimation sheet and the supplementary materials.

- Expand this program to Botswana, Namibia, and Malawi

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $10,000

- 2023: $25,000

- Expand this program to Botswana, Namibia, and Malawi

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $14,000

- 2023: $31,000

- Hire a Regional Manager

- Introduce this program in Botswana, Namibia, and Malawi

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $3,000

- 2023: $10,000

- Expand this program to Nigeria and Ghana

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $5,000

- 2023: $0

- Generate localized research work on the impact of industrial animal agriculture

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $0

- 2023: $10,000

- Potentially start a program, ‘Ban Live Export’, to ban live the export of animals by sea

- Hire a Communications Director, a Policy Director, a Strategy Manager, and a Digital Manager

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: -$132,00022

- 2023: -$51,000

How CAAWO would spend an additional $100,000

- Expand the cage-free and sow stall free campaigns

- Hire new staff in the next six months rather than wait until 2023

- Hire a Digital Manager and a Policy Director

How CAAWO would spend an additional $1,000,000

- Open up new offices in Botswana, Namibia, and Malawi, and hire new staff

- Invest in working equipment

- Start a research program with regional academic institutions to research scientific solutions for proposed alternatives to animal suffering

Estimate of expenditure

- 2022: $210,000

- 2023: $0

Our Assessment

CAAWO plans to focus future expansions on their following programs: cage-free campaign, sow stall free campaign, humane education, legal research, and industrial agriculture research. In addition, they look to hire staff and potentially start a program to ban live export. For donors influenced by ACE wishing to donate to CAAWO, we estimate that the organization can effectively absorb funding that we expect to come with a recommendation status.

Based on i) CAAWO’s own projections that their revenue will cover their expenditures, ii) our assessment that they can use additional reserves, and iii) our assessment that they could effectively absorb an additional $100,000, we believe that CAAWO has room for $170,000 of additional funding in 2022 and no additional room for funding in 2023. See our Programs criterion for our assessment of the effectiveness of the programs.

It is possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or that they could come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. If a charity receives a recommendation as Top Charity, we check in mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented above to indicate whether we still expect them to be able to effectively absorb additional funding at that time.

Cost Effectiveness

Method

A charity’s recent cost effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component in understanding how cost effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources over the past 18 months and compare that to the outputs they have achieved in each of their main programs during that time. We seek to understand whether each charity has been successful at implementing their programs in the recent past and whether past successes were achieved at a reasonable cost. We only complete an assessment of cost effectiveness for programs that started in 2019 or earlier and that have expenditures totaling at least 10% of the organization’s annual budget.

Below, we report what we believe to be the key outputs of each program (for a complete list of outputs reported by the CAAWO, see this document), as well as the total program expenditures. To estimate total program expenditures, we take the reported expenditures for each program and add a portion of their non-program expenditures weighted by the size of the program. This allows us to incorporate general organizational running costs into our consideration of cost-effectiveness.

We spend a significant portion of our time during the evaluation process verifying the outputs charities report to us. We do this by (i) searching for independent sources that can help us verify claims, and (ii) directing follow-up questions to charities to gather more information. We adjusted some of the reported claims based on our verification work.

Information and Analysis

Overview of key outputs

We did not include a chart representing CAAWO’s program expenditures for the last 18 months due to insufficient information on their expenditures per program.

- Engaged seven companies in South Africa, Tanzania, and Kenya to make or follow up on their cage-free commitments (alone or in cooperation with other organizations)

- Engaged with the National Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development (DALRRD) and with the South African Bureau of Standards (SABS) on the continued use of battery cages in chicken egg production facilities

- Engaged companies to adopt gestation-crate-free policies

Developed and hosted an introductory course, “Animal Welfare in Africa” on their website (so far, two people have signed up for the course)

- Drafted a report, together with Lawyers for Animal Protection in Africa, on the state of legislation relating to farmed animal welfare in South Africa and Kenya

- Drafted a research report on the impact of industrial farming on the population, the environment, and welfare of animals in South Africa

- There is no evidence of any key outputs from this program in the past 18 months

Our Assessment

We could not assess the cost-effectiveness of CAAWO’s programs due to their short track record—their programs started in 2020 and 2021—and lack of information about specific outcomes and expenditures per program.

Leadership and Culture

A charity that performs well on this criterion has strong leadership and a healthy organizational culture. The way an organization is led affects its organizational culture, which in turn impacts the organization’s effectiveness and stability.23 The key aspects that ACE considers when examining leadership and culture are reviewed in detail below.

Method

We review aspects of organizational leadership and culture by capturing staff and volunteer perspectives via our culture survey, in addition to information provided by top leadership staff (as defined by each charity).

Assessing leadership

First, we consider key information about the composition of leadership staff and board of directors. There appears to be no consensus in the literature on the specifics of the relationship between board composition and organizational performance,24 therefore we refrain from making judgements on board composition. However, because donors may have preferences on whether the Executive Director (ED) or other top executive staff are board members or not, we note when this is the case. According to the Council on Foundations,25 risks of EDs serving as board members include conflicts of interest when the board sets the ED’s salary, complicated reporting relationships, and blurred lines between governing bodies and staff. On the other hand, an ED that is part of a governing board can provide context about day-to-day operations and ultimately lead to better-informed decisions, while also giving the ED more credibility and authority.

We also consider information about leadership’s commitment to transparency by looking at available information on the charity’s website, such as key staff members, financial information, and board meeting notes. We require organizations selected for evaluation to be transparent with ACE throughout the process. Although we value transparency, we do not expect all organizations to be transparent with the public about sensitive information. For example, we recognize that organizations and individuals working in some regions or on some interventions could be harmed by making information about their work public. In these cases, we favor confidentiality over transparency.

In addition, we utilize our culture survey to ask staff to identify the extent to which they feel that leadership is competently guiding the organization.

Organizational policies

We ask organizations undergoing evaluation to provide a list of their human resources policies. We also request the organization’s benefit policies regarding time off, health care, and training and professional development. As policies vary across countries and cultures, we do not evaluate charities based on their set of policies and do not expect effective charities to have all policies in place.

ACE usually elicits the views of staff and volunteers through our culture survey. However, CAAWO currently has only two non-leadership staff members, and we chose not to administer ACE’s culture survey in this case because we cannot guarantee anonymity.

ACE believes that the animal advocacy movement should be safe and inclusive for everyone. Therefore, we also collect information about policies and activities regarding representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI). We use the terms “representation” and “diversity” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of certain social identity characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries).26 Additionally, we believe that effective charities must have human resources policies against harassment27 and discrimination,28 and that cases of harrassment and discrimination in the workplace should be addressed appropriately. If a specific case of harassment or discrimination from the last 12 months is reported to ACE by several current or former staff members or volunteers at a charity, and said case remains unaddressed, the charity in question is ineligible to receive a recommendation from ACE.

Information and Analysis

Leadership staff

In this section, we list each charity’s President (or equivalent) and/or Executive Director (or equivalent), and we describe the board of directors. This is completed for the purpose of transparency and to identify the relationship between the ED and board of directors.

- Executive Director (ED): Tozie Zokufa, involved in the organization for three years

- Number of members on board of directors: three members, including Executive Director (ED) Tozie Zokufa

CAAWO did not have a transition in leadership in the last year.

CAAWO has been transparent with ACE during the evaluation process. CAAWO’s audited financial documents are not available on the charity’s website or GuideStar. Lists of board members and key staff members are available on the charity’s website.

Culture

CAAWO has three staff members who are also part of leadership, two contractors, and no volunteers. Therefore, due to the few non-leadership staff and concerns of anonymity, we did not send a culture survey to CAAWO.

CAAWO has a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. CAAWO offers paid time off and sick days, but no healthcare coverage. Additional policies are listed in the table below.

General compensation policies

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A formal compensation policy to determine staff salaries | |

| Paid time off | |

| Sick days and personal leave | |

| Healthcare coverage | |

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| Annual (or more frequent) performance evaluations | |

| Formal onboarding or orientation process | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support | |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Remote work option | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable)

Note: CAAWO currently does not have any volunteers or interns. They let us know that they will consider bringing on volunteers or interns once they resume in-person events. |

CAAWO has a code of conduct, but no other staff policies against harassment and discrimination.

Policies related to representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI)

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics/conduct | |

| A written statement that the organization does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels, up to and including the board of directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| Documentation of all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

Our Assessment

CAAWO is a small organization that is composed mostly of leadership staff. We think that CAAWO could benefit from creating staff policies against harassment and discrimination as their number of staff members increase.

On average, our team considers advocating for welfare improvements to be a positive and promising approach. However, there are different viewpoints within ACE’s research team on the effect of advocating for animal welfare standards on the spread of anti-speciesist values. There are concerns that arguing for welfare improvements may lead to complacency related to animal welfare and give the public an inconsistent message—e.g., see Wrenn (2012). In addition, there are concerns with the alliance between nonprofit organizations and the companies that are directly responsible for animal exploitation, as explored in Baur and Schmitz (2012).

The weightings used for calculating these country scores are scale (25%), tractability (55%), and regional influence (20%).

We don’t believe that the number of individuals is the only relevant characteristic for scale, and we don’t necessarily believe that groups of animals should be prioritized solely based on the scale of the problem. However, number of animals is one characteristic we use for prioritization.

We estimate there are 10 quintillion, or 1019, wild animals alive at any time, of whom we estimate at least 10 trillion are vertebrates. It’s notable that Rowe (2020) estimates that 100 trillion to 10 quadrillion (or 1014 to 1016) wild invertebrates are killed by agricultural pesticides annually.

For arguments supporting the view that the most important consideration of our present actions should be their impact in the long term, see Greaves & MacAskill (2019) and Beckstead (2019).

Animal Advocacy Africa (Stumpe, 2021) makes a case that African animal advocacy groups should prioritize farmed animals.

See Bianchi et al. (2018a) for a summary of this literature.

See, for example, Animal Charity Evaluators (2016), Tiplady, Walsh, & Phillips (2013), and Tonsor & Olynk (2011).

To be selected for evaluation, we require that a charity has a revenue of at least about $50,000 and faces no country-specific regulatory barriers to receiving money from ACE.

CAAWO received a Movement Grant of $10,000 in October, 2020.

A negative amount for change in expenditure here means that the reported difference in program costs between 2022 and 2021 is larger than the total change in expenditure. For details, see the RFMF sheet.

Examples of such social identity characteristics are: race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, and genetic information.

Harassment can be non-sexual or sexual in nature: ACE defines non-sexual harassment as unwelcome conduct—including physical, verbal, and nonverbal behavior—that upsets, demeans, humiliates, intimidates, or threatens an individual or group. Harassment may occur in one incident or many. ACE defines sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances; requests for sexual favors; and other physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors of a sexual nature when (i) submission to such conduct is made explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment; (ii) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting the targeted individual; or (iii) such conduct has the purpose or effect of interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

ACE defines discrimination as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of or hostility toward an individual on the basis of certain characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries), such as race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, or genetic information.