Dharma Voices for Animals

Archived Review| Review Published: | 2021 |

| Current Version | 2023 |

Archived Version: 2021

What does DVA do?

Dharma Voices for Animals (DVA) is the only international Buddhist animal rights organization in the world. The majority of their work takes place in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, and the U.S., but they also work in Germany, Brazil, Finland, Myanmar, and Australia. DVA’s programs align with specific contexts and priorities in the countries where they work. Many of their programs focus on diet change, however, they also lobby for animal welfare legislation, provide veterinary care, and work with restaurant owners to encourage them to transition their businesses to veganism.

What are their strengths?

DVA’s programs primarily focus on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we think is a high-priority cause area due to the large number of animals involved. Their work has potential to affect large numbers of animals given its global breadth. For each of their chapters in developing regions, DVA has a cultural advisor to prevent and address potential power imbalances between developed and developing country parties. Furthermore, DVA’s staff agree that the organization is led competently.

What are their weaknesses?

We consider DVA’s work providing veterinary care to be lower-priority because of the relatively small number of animals it affects. In addition, it is difficult for us to assess the effectiveness of some of DVA’s programs due to the small amount of resources allocated to them. We also think that DVA could benefit from creating staff policies against harassment and discrimination.

Why did we recommend them?

Dharma Voices for Animals works with Buddhist communities in countries with relatively young and small animal advocacy movements, which we think is a promising avenue for pursuing large-scale change for farmed animals. We think DVA is well-positioned to contribute to the growth of the animal advocacy movement in these communities and countries.

We find DVA to be an excellent giving opportunity because of their strong programs aimed at increasing the availability of animal-free products and strengthening the animal advocacy movement in relatively neglected regions.

DVA received one ACE Movement Grant in April 2019 and one in June 2021.

Programs

A charity that performs well on this criterion has programs that we expect are highly effective in reducing the suffering of animals. The key aspects that ACE considers when examining a charity’s programs are reviewed in detail below.

Method

In this criterion, we assess the effectiveness of each of the charity’s programs by analyzing (i) the interventions each program uses, (ii) the outcomes those interventions work toward, (iii) the countries in which the program takes place, and (iv) the groups of animals the program affects. We use information supplied by the charity to provide a more detailed analysis of each of these four factors. Our assessment of each intervention is informed by our research briefs and other relevant research.

At the beginning of our evaluation process, we select charities that we believe have the most effective programs. This year, we considered a comprehensive list of animal advocacy charities that focus on improving the lives of farmed or wild animals. We selected farmed animal charities based on the outcomes they work toward, the regions they work in, and the specific animal group(s) their programs target. We don’t currently consider animal group(s) targeted as part of our evaluation for wild animal charities, as the number of charities working on the welfare of wild animals is very small.

Outcomes

We categorize the work of animal advocacy charities by their outcomes, broadly distinguishing whether interventions focus on individual or institutional change. Individual-focused interventions often involve decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Institutional change involves improving animal welfare standards, increasing the availability of animal-free products, or strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

We believe that changing individual habits and beliefs is difficult to achieve through individual outreach. Currently, we find the arguments for an institution-focused approach1 more compelling than individual-focused approaches. We believe that raising welfare standards increases animal welfare for a large number of animals in the short term2 and may contribute to transforming markets in the long run.3 Increasing the availability of animal-free foods, e.g., by bringing new, affordable products to the market or providing more plant-based menu options, can provide a convenient opportunity for people to choose more plant-based options. Moreover, we believe that efforts to strengthen the animal advocacy movement, e.g., by improving organizational effectiveness and building alliances, can support all other outcomes and may be relatively neglected.

Therefore, when considering charities to evaluate, we prioritize those that work to improve welfare standards, increase the availability of animal-free products, or strengthen the animal advocacy movement. We give lower priority to charities that focus on decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Charities selected for evaluation are sent a request for more in-depth information about their programs and the specific interventions they use. We then present and assess each of the charities’ programs. In line with our commitment to following empirical evidence and logical reasoning, we use existing research to inform our assessments and explain our thinking about the effectiveness of different interventions.

Countries

A charity’s countries and regions of operations can affect their work with regard to scale, neglectedness, and tractability. We prioritize charities in countries with relatively large animal agricultural industries, few other charities engaged in similar work, and in which animal advocacy is likely to be feasible and have a lasting impact. In our charity selection process, we used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI), which combines proxies for scale, tractability, and global influence to create country scores.4 To assess neglectedness, we used our own data on the number of organizations that we are aware of working in each country. Below we present these measures for the countries that Dharma Voices for Animals (DVA) operates in.

A note about long-term impact

Each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.5 The potential number of animals affected increases over time due to population growth and an accumulation of generations. Thus, we would expect that the long-term impacts of an action would likely affect more animals than the short-term impacts of the same action. Nevertheless, we are highly uncertain about the particular long-term effects of each intervention. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew toward overemphasizing short-term effects.

Information and Analysis

Cause areas

DVA’s programs focus primarily on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we think is a high-priority cause area.

DVA also works on companion animal welfare. We do not think this cause area is a high priority because it is relatively less neglected. However, we believe DVA focuses on this area as a way to initially engage with monastics at Buddhist temples in order to develop further advocacy there.

Countries

DVA develops their programs in the U.S., Thailand, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Germany, Brazil, Finland, Myanmar, and Australia. However, the majority of their work seems to be conducted in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, and the U.S. Their headquarters are in the U.S.

We used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI) with the suggested weightings of scale (25%), tractability, (55%) and influence (20%) to determine each country’s total FAOI score. We report this score along with the country’s global ranking from a total of 60 countries in the following format: FAOI score(global ranking). The U.S., Thailand, Vietnam, Germany, Brazil, Finland, Myanmar, and Australia have the following scores and rankings, respectively: 53.92(2), 17.32(21), 18.68(20), 33.52(3), 32.87(5), 7.4(51), 8.26(49), and 19.09(18). The FAOI does not include Sri Lanka. According to the comprehensive list of charities we are aware of, there are about 724 farmed animal advocacy organizations, excluding sanctuaries, worldwide. From this list, we found 220 in the U.S., 2 in Thailand, 3 Vietnam, 40 in Germany, 15 in Brazil, 6 in Finland, 0 in Myanmar, 28 in Australia, and 1 in Sri Lanka. We believe that farmed animal advocacy in the U.S., Germany, and Brazil are particularly high priority because of their high overall FAOI scores, but work there is not as neglected as it is in Thailand and Vietnam, which also have moderately high scale and tractability FAOI scores. Advocacy work in Myanmar is relatively neglected given the scale of the problem there: Myanmar’s FAOI scale score of 4.04 is higher than Germany’s (3.39).6

Description of programs

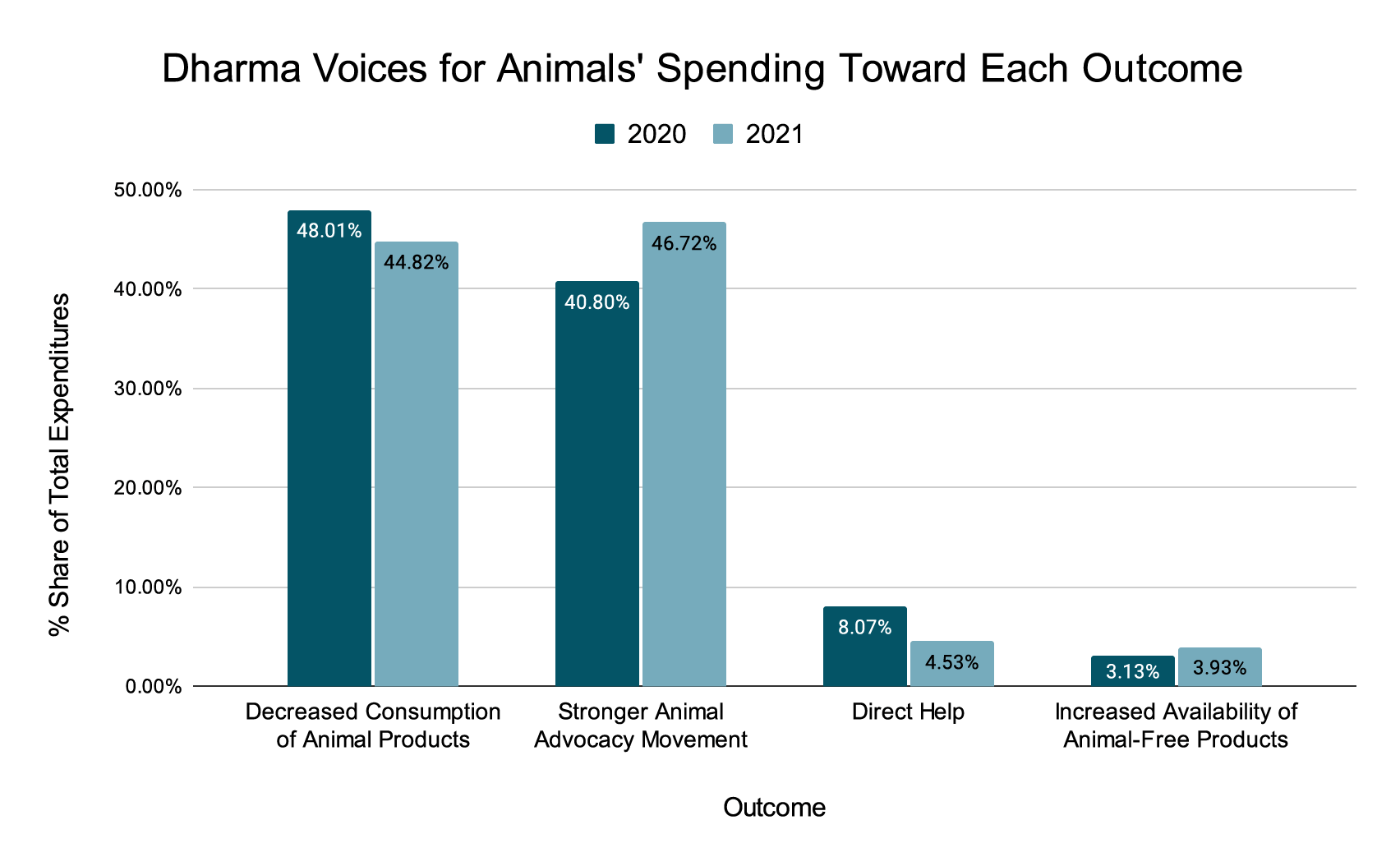

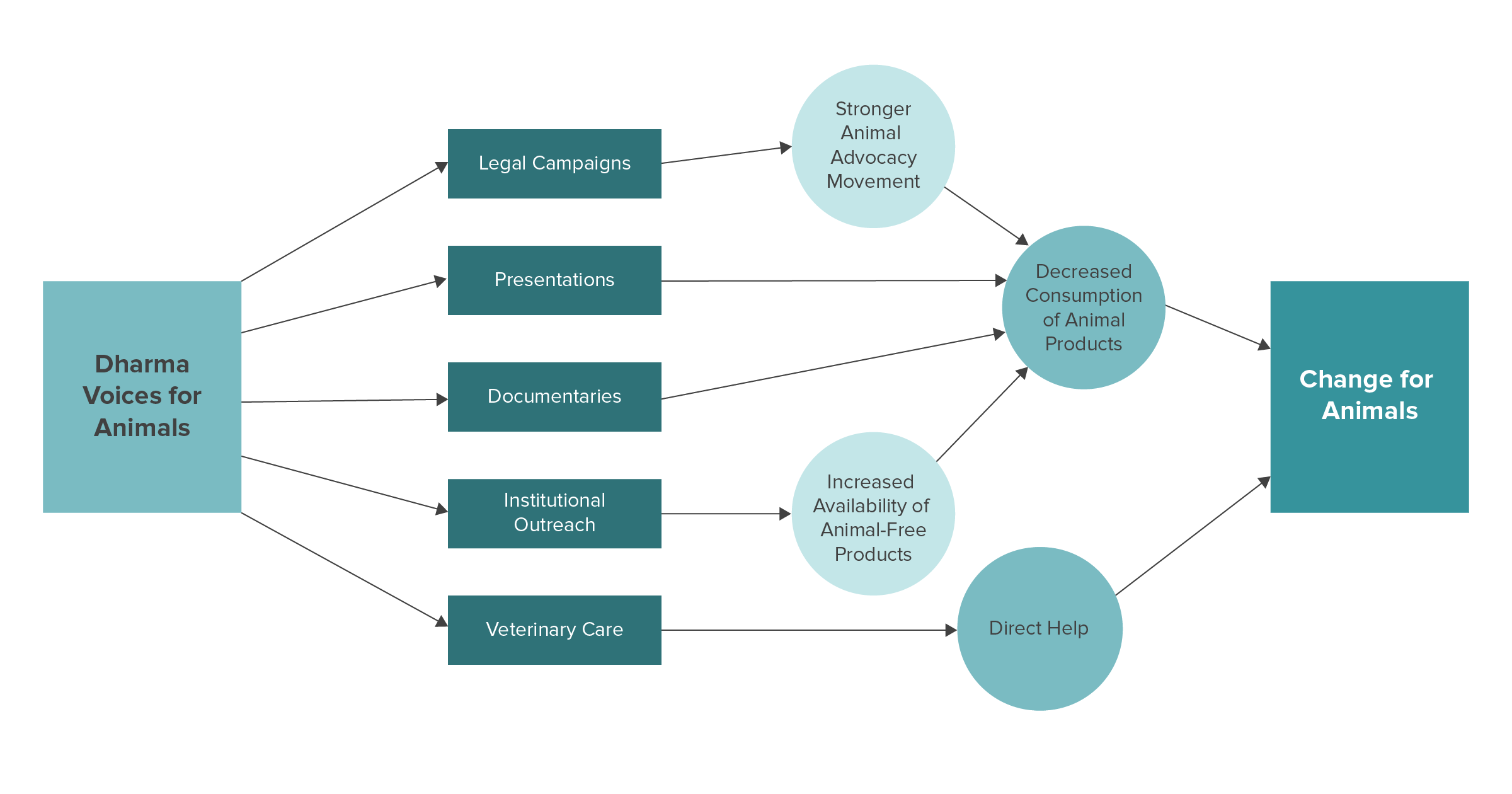

DVA pursues different avenues for creating change for animals. Their work focuses on decreasing the consumption of animal products and strengthening the animal advocacy movement. To a lesser extent, their work also aims to increase the availability of animal-free products and provide direct help to companion animals.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

Below, we describe each of DVA’s programs, listed in order of the financial resources devoted to them in 2020 (from highest to lowest). We list major accomplishments for each program, if a track record is available.

DVA’s programs

This program focuses on advocating for the passage of Sri Lanka’s Animal Welfare Bill and promoting its enforcement through social media and Parliament member engagement.

Main interventions

- Legal campaigns

- Police training

- Presentations

Key historical accomplishments

- Received explicit commitments from 141 members of Parliament that they will vote for the bill (as of 2021)

- Sponsored a national oratory contest

- Delivered 74 presentations

This program focuses on reaching out to individuals in Sri Lanka to reduce the consumption of animal products.

Main interventions

- Presentations

- Radio programs

- Conferences

Key historical accomplishments

- Delivered more than 400 presentations at Dhamma schools, army posts, factories, universities, and health inspector conferences (as of 2021)

- Delivered 30 Friday morning half-hour programs on a radio show (2020–2021)

- Hosted the second annual Asian Buddhist Animal Rights Conference (2017)

- Held three press conferences (2017–2019) and a nationwide art contest for children (2019)

This program focuses on creating change in Thailand’s Buddhist community (e.g., monastics, monks, and monastics’ followers) to reduce their consumption of animal products by reinforcing Buddhist ethics.

Main interventions

- Presentations

- Cooking classes

- Social media

Key historical accomplishments

- Influenced hundreds of the most respected monastics to reduce their consumption of animal products

- Delivered 20 presentations at Buddhist temples in Thailand about health benefits of vegan diets

- Delivered two cooking classes together with Sinergia Animal

This program focuses on creating change in Vietnam’s Buddhist community to decrease their consumption of animal products.

Main interventions

- Presentations

- Conferences

- Cooking classes

- Documentaries

- Government outreach

Key historical accomplishments

- Released a documentary film on why some Vietnamese people have choose to be vegetarian (2019)

- Hosted the third annual Asian Buddhist Animal Rights Conference (2018)

- Delivered presentations at 10 temples with 1000 Buddhist followers each (2019–2020)

This program focuses on providing veterinary care to companion animals (e.g., dogs, cats, cows, and rabbits) living in and around Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka.

Main interventions

- Veterinary care

Key historical accomplishments

- Visited 10 temples in 2019, 30 temples in 2020, and 20 temples in 2021, providing veterinary care to an average of 19 animals (10 dogs, five cats, one cow, two rabbits, and one chicken) per temple

This program focuses on influencing Buddhist centers in the U.S. to serve only vegan food.

Main interventions

- Institutional outreach

- Documentaries

- Social media

Key historical accomplishments

- Released the documentary film Animals and the Buddha (2012) and translated it into 12 additional languages

- Influenced five Buddhist retreat centers to serve almost 100% vegan food (as of 2021)

- Created a database of U.S. Buddhist centers

- Achieved a social media presence with over 5,000 Facebook followers, 1,500 YouTube subscribers, and 5,300 Instagram followers

- Created DVA live interviews (the “Speakers Series”)

This program focuses on establishing chapters in other countries to advocate for diet change at Buddhist centers and provide support to center members who are vegetarian or vegan.

Main interventions

- Institutional outreach

- Community meetings

- Fundraising

Key historical accomplishments

- Established chapters in Brazil, Germany, Myanmar, Australia, Finland, and the U.S. (as of 2021)

- Hosted three Chapter Leader Conferences in Chicago (2016), Sri Lanka (2017), and Minnesota (2019)

This program focuses on mentoring restaurant owners to transition to vegan restaurants in Vietnam.

Main interventions

- Institutional outreach

Key historical accomplishments

- Successfully transitioned four Hanoi-area restaurants and one Hue restaurant to become vegan (as of 2021)

Research for intervention effectiveness

Institutional outreach

Currently, there is no peer-reviewed research specifically about institutional outreach to influence the availability of animal-free products. However, we could learn from studies that investigate the effectiveness of outreach to hospitals and schools on increasing the availability of “healthy foods” (specifically fruits, vegetables, and whole grains). We believe that reaching out to nonprofit institutions with the effective strategies identified in these studies has the potential to increase the availability of animal-free foods, based on high participation and success rates in health food outreach to schools and hospitals. Some of these strategies included i) working with the local hospital association and hospital workers’ unions to encourage participation, ii) enlisting in-depth assistance from dietitians, and iii) providing advice on how to incorporate new standards into existing operations. However, due to concerns about the generalizability of this intervention to outreach for animal-free foods, we believe that more research is needed.

Individual outreach

There is mixed evidence regarding the effectiveness of humane education on changing diet patterns in individuals. According to a recent two-year study,7 distributing animal advocacy pamphlets to individuals was associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in animal product consumption for a small subset of the sample: those who identified as vegetarian, those who thought more about animal welfare, and those who said they were willing to change their diet. However, this effect on diet only lasted for two months—the leafleting intervention did not have any statistically significant effects over the course of the entire study. Between this study and ACE’s 2017 meta-analysis about leafleting, we are uncertain about the effectiveness of individual outreach methods, such as distributing information pamphlets.

Some empirical studies suggest that providing people with written information may increase their intention to consume less meat.8 However, it is uncertain how written information may affect attitudes toward animal products other than meat, how the format and the specific content of the message may affect the impact on intentions, and whether changes in intentions translate into changes in consumer behavior. There is some evidence of a weak negative correlation between media coverage of animal welfare and meat demand.9 However, there is likely to be a large variation in the reach of these interventions, and it is uncertain whether they causally contribute to reducing the consumption of animal products.

Legal work

DVA works on legal and legislative advocacy. We are not confident about the effectiveness of legal outreach because there is currently a lack of research on this topic. However, we suspect that the effects of legal change could be particularly long-lasting, despite the long time frame compared to other forms of change. We also think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to have an impact on a large number of animals.

We believe that the enforcement of animal welfare laws is important because without enforcement, there will not be a positive real-world effect on animals. There is currently a lack of research regarding the effectiveness of legal enforcement on the welfare of animals. However, there is preliminary evidence of a potential discrepancy between animal welfare laws in theory and in practice: the “enforcement gap”.10 There are many factors that could cause this discrepancy, including i) a lack of reporting of animal cruelty acts, ii) ambiguous language in animal welfare legislation, and iii) the realities of enforcement. DVA reports that after the Animal Welfare bill becomes law, they will educate the public on how it protects animals and how Sri Lankan citizens can report violations to protect animals. DVA will also conduct training for all 25 district police stations.

Movement building

There is currently no empirical evidence that reviews the effectiveness of movement building in animal advocacy. However, we believe that capacity-building projects have the potential to help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Furthermore, building alliances with key influencers, institutions, or social movements could expand the audience and impact of animal advocacy organizations and projects, leading to net positive outcomes for animals. Additionally, ACE’s 2018 research and Harris11 suggest that capacity building and building alliances are currently neglected relative to other interventions aimed at influencing public opinion and industry.

Veterinary care

We currently do not prioritize veterinary care for companion animals because this intervention helps a smaller number of animals, is better funded, and is less neglected than interventions that help farmed or wild animals. We think this intervention can be used by charities for more indirect purposes, such as community and alliance building, which can increase the effectiveness of this intervention.

Our Assessment

We think that DVA’s legislation program and worldwide chapters program—aimed at strengthening the animal advocacy movement—are particularly effective, but there is little evidence supporting this claim. We also think that their veterinary care program may be less effective than their other programs because providing direct help to companion animals is not as neglected as other cause areas.

We consider DVA’s work in the U.S., Germany, and Brazil to be particularly effective based on the high number of animals, high tractability, and high global influence in those countries. We also consider DVA’s work in Thailand and Vietnam to be important because animal advocacy is relatively neglected given the moderately high number of animals there.

Overall, we think that about half of DVA’s spending on programs goes toward outcomes, countries, and helping species that we think are a high priority.

Room for More Funding

A new recommendation from ACE could lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding. In this criterion, we investigate whether a charity is able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in or, if the charity has a prior recommendation status, whether they will continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation.

Method

In the following section, we inspect the charity’s plans for expansion as well as their financials, including revenue and expenditure projections.

The charities we evaluate typically receive revenue from a variety of different sources, such as individual donations or grants from foundations.12 In order to guarantee that a charity will raise the funds needed for their operations, they should be able to predict changes in future revenue. To estimate charities’ room for more funding, we request records of their revenue since 2019 and ask what they predict their revenue will be in 2021–2023. A review of the literature on nonprofit finance suggests that revenue diversity may be positively associated with revenue predictability if the sources of income are largely uncorrelated.13 However, a few sources of large donations—if stable and reliable—may also be associated with high performance and growth. Therefore, in this criterion, we also indicate the charities’ major sources of income.

We present the charities’ reported plans for expansion of each program as well as other planned changes for the next two years. We do not make active suggestions for additional plans. However, we ask charities to indicate how they would spend additional funding that we expect would come in as a result of a new recommendation from ACE, considering that a Standout Charity status and a Top Charity status would likely lead to a $100,000 or $1,000,000 increase in funding, respectively. Note that we list the expenditures for planned non-program expenses but do not make any assessment of the charity’s overhead costs in this criterion, given that there is no evidence that the total share of overhead costs is negatively related to overall effectiveness.14 However, we do consider relative overhead costs per program in our Cost-Effectiveness criterion. Here we focus on evaluating whether additional resources are likely to be used for effective programs or other beneficial changes in the organization. The latter may include investments into infrastructure and efforts to retain staff, both of which we think are important for sustainable growth.

It is common practice for charities to hold more funds than needed for their current expenses (i.e., reserves) in order to be able to withstand changes in the business cycle or other external shocks that may affect their incoming revenue. Such additional funds can also serve as investments into future projects in the long run. Thus, it can be effective to provide a charity with additional funds to secure the stability of the organization or provide funding for larger, future projects. We do not prescribe a certain share of reserves, but we suggest that charities hold reserves equal to at least one year of expenditures, and we increase a charity’s room for more funding if their reserves in 2021 are less than 100% of their projected total expenditure.

Finally, we aggregate the financial information and the charity’s plans to form an assessment of their room for more funding. All descriptive data and estimations can be found in this sheet. Our assessment of a charity’s ability to effectively absorb additional funding helps inform our recommendation decision.

Information and Analysis

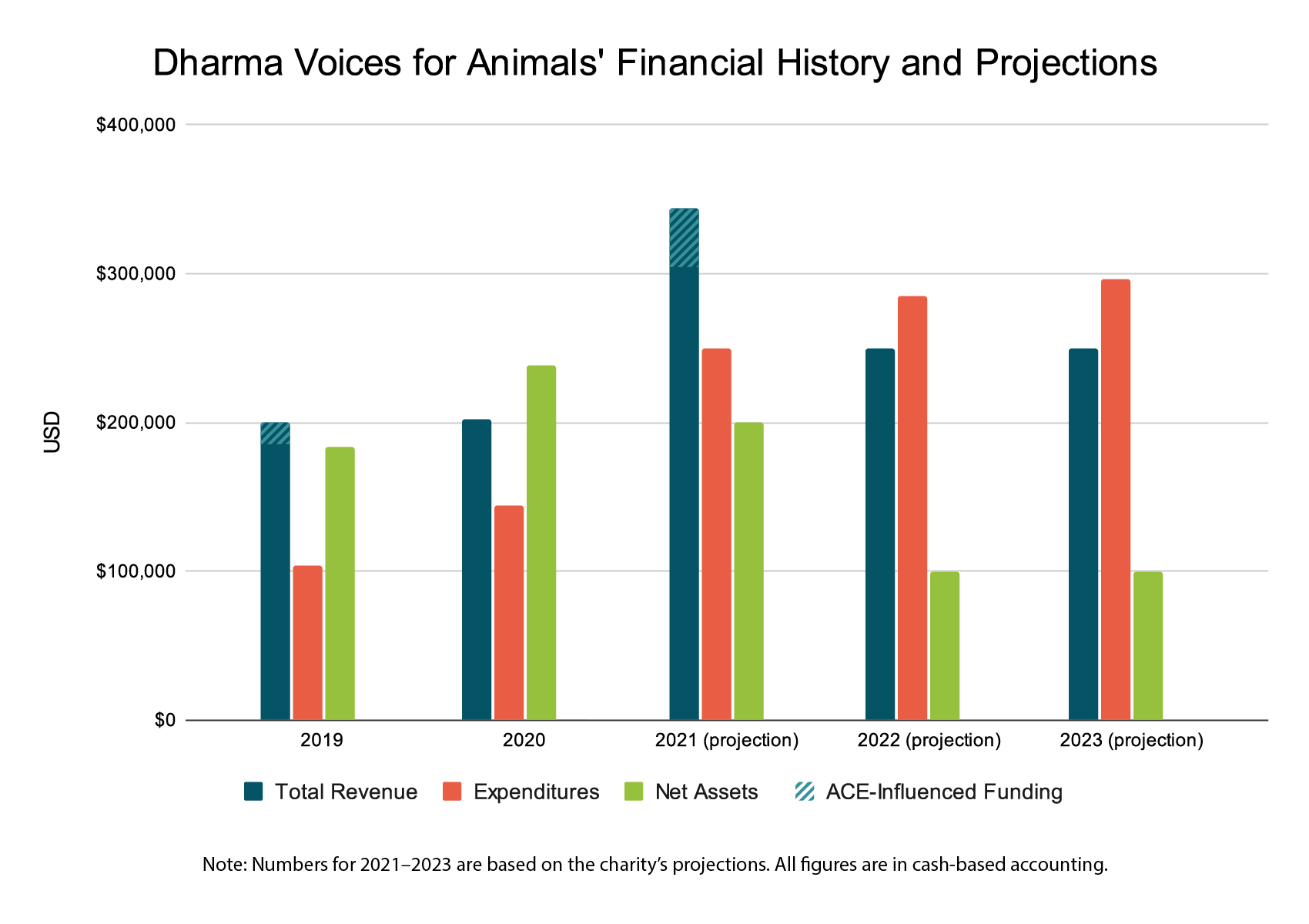

The chart below shows DVA’s revenues, expenditures, and net assets from 2019–2020, as well as projections for the years 2021–2023. The information is based on the charity’s past financial data and their own predictions for the years 2021–2023.

DVA receives the majority of their income from donations, 1.14% from their own work, and 0% from capital investments.15 In 2020, they received 86% of their funding from donations larger than 20% of their annual revenue.16 They expect their revenue to increase more in 2021 than in the previous years.17

According to DVA’s reported projections, their estimated revenue in 2022 will not cover their expenditures. Subtracting their projected annual revenue from their projected annual expenditures, we find a funding gap of about $35,000 in 2022 and about $46,000 in 2023.

DVA outlined that if they were to receive an additional $100,000 per year, it would be distributed over infrastructure and their programs in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam. If they were to receive an additional $1,000,000 per year, it would be distributed over infrastructure, diet change advocacy in U.S. Buddhist centers, and their programs in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam. We believe that DVA could effectively absorb at least an additional $100,000 per year, but not an additional $1,000,000 per year, beyond their existing funding gap. DVA notes they could effectively use an additional $551,000, whereas a $1 million grant would require a restructuring of the organization.

With about 80% of their current annual expenditures held in net assets—as reported by DVA for 2021—we believe that they could benefit from holding a larger amount of reserves. As such, we add additional funding to replenish their reserves to the charity’s plans for expansion.

Below we list DVA’s plans for expansion for each of their programs as well as other planned expenditures, such as administrative costs, wages, and training. We do not verify the feasibility of the plans or the specifics of how changes in expenditure will cover planned expansions. Reported changes in expenditure are based on the charity’s own estimates of changes in program expenditures for 2021–2022 and 2022–2023.

DVA plans to expand their diet change programs in Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam; their veterinary care program in Sri Lanka; their restaurant owner mentorship program in Vietnam; and their diet change advocacy program in Buddhist centers in the U.S. In addition, they plan to organize a vegan fest in Vietnam, hire team members for general support, and potentially expand to China.

- Phase out after grant period ends

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: -$30,000

- 2023: -$43,000

- Hire four new Regional Coordinators to diversify venues for presentations

- Develop a relationship with the Government Medical Officers’ Association

- Expand communications

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $0

- 2023: $9,000

- Hire an Assistant Director to double the number of presentations

- Hire a physician for presentations

- Hire a dietician for cooking classes

- Expand relationships with monks through social media

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $14,000

- 2023: $10,000

- Hire or train team members to increase the number of presentations, including cooking classes, once COVID-19 restrictions lift

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $8,000 to $10,000

- 2023: $20,000

- Increase the number of temples to treat more animals

- Potentially increase the number of presenters

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $3,000

- 2023: $0

- Support U.S. Buddhist centers that are targeted for diet change

- Produce a video

- Potentially hire a coordinator18

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $5,000

- 2023: $10,000

- No changes

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $0

- 2023: $0

- Hire an additional cook, dietician, or nutritionist

- Potentially hire an additional restaurant owner

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $9,000

- 2023: $5,000

- Organize a vegan fest in Hanoi, Vietnam with a projected attendance of 45,000 people

- Potentially expand to China

- Increase administrative support

- Hire new team members including an Operations Director, a Director for their diet change advocacy program in U.S. Buddhist centers, and a Fundraising Consultant

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $15,000 to $19,000

- 2023: -$11,00019

- Hire four additional Regional Coordinators in Sri Lanka

- Produce 15,000 additional copies of their cookbook

- Increase the salary of the Thailand Director

- Expand the program that provides plant-based meals and blood tests to monks who are sick

- Support restaurant owners in Vietnam to transition their restaurants to plant-based ones

- Organize a three-day vegan fest

- Hire a Director for their diet change advocacy program in U.S. Buddhist centers

How DVA would spend an additional $1,000,00020

- Add four additional professional presenters—including doctors, public health experts, dieticians, and nurses—in Thailand

- Conduct a scientific study of the health benefits of vegan diets using monastics

- Hire four people in Vietnam, including a professional vegan cook, a dietician, and a business consultant with restaurant experience

- Increase the capacity of the Director of the diet change advocacy program in U.S. Buddhist centers to full-time

- Increase the capacity of the Communications Director from 20 hours per week to full-time

- Increase reserves

Cost of replenishing reserves

Estimate of expenditure

- 2022: $50,000

- 2023: $150,000

Our Assessment

DVA plans to focus future expansions on their diet change programs in Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam; their veterinary care program in Sri Lanka; their restaurant owner mentorship program in Vietnam; and their diet change advocacy program in Buddhist centers in the U.S. In addition, they plan to organize a vegan fest in Vietnam, hire team members for general support, and potentially expand to China. For donors influenced by ACE wishing to donate to DVA, we estimate that the organization can effectively absorb funding that we expect to come with a recommendation status.

Based on i) DVA’s own projections that their revenue will not cover their expenditures, ii) our assessment that they can use additional reserves, and iii) our assessment that they could effectively absorb an additional $100,000, we believe that overall, DVA has room for $185,000 of additional funding in 2022 and $331,000 in 2023. See our Programs criterion for our assessment of the effectiveness of their programs.

It is possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or that they could come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. If a charity receives a recommendation as Top Charity, we check in mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented above to indicate whether we still expect them to be able to effectively absorb additional funding at that time.

Cost Effectiveness

Method

A charity’s recent cost effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component in understanding how cost effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources over the past 18 months and compare that to the outputs they have achieved in each of their main programs during that time. We seek to understand whether each charity has been successful at implementing their programs in the recent past and whether past successes were achieved at a reasonable cost. We only complete an assessment of cost effectiveness for programs that started in 2019 or earlier and that have expenditures totaling at least 10% of the organization’s annual budget.

Below, we report what we believe to be the key outputs of each program, as well as the total program expenditures. To estimate total program expenditures, we take the reported expenditures for each program and add a portion of their non-program expenditures weighted by the size of the program. This allows us to incorporate general organizational running costs into our consideration of cost effectiveness.

We spend a significant portion of our time during the evaluation process verifying the outputs charities report to us. We do this by (i) searching for independent sources that can help us verify claims, and (ii) directing follow-up questions to charities to gather more information. We adjusted some of the reported claims based on our verification work.

Information and Analysis

Overview of expenditures

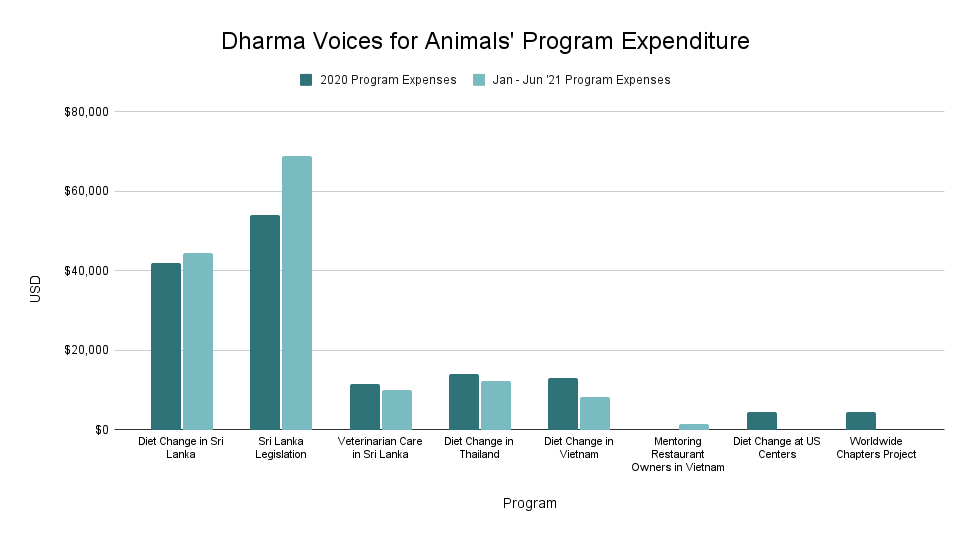

The following chart shows DVA’s total program expenditures from January 2020 – June 2021.

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Made 74 live presentations, concentrating on Buddhist temples and health care centers, to encourage the passage of an updated animal welfare bill

- DVA’s President spent four weeks in Sri Lanka appearing at events all over the country, holding press conferences, giving individual interviews to the press, and speaking to government officials about the bill

- Sponsored a national oratory contest for young adults on why the animal welfare bill is good for Sri Lanka and why animals should be protected

- Directly addressed the ministry in a video published on Facebook

Expenditures21 (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $121,000

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Gave over 400 live presentations at Sunday schools, army posts, factories, universities, and conferences throughout Sri Lanka to encourage diet change

- Continued to grow social media networks—their Facebook page surpassed 113,000 followers and their YouTube channel now contains 222 videos featuring political leaders, celebrities and sports personalities (as of June 2021)

- Utilized the DVA radio show to air 30 Friday morning half-hour programs with speakers who advocate for a compassionate diet

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $86,00022

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Hired Chirra Taworntawat (Banks)—a vegan, former monk, and YouTube influencer—as Director of DVA’s Thailand Project

- Gave 20 live presentations at Buddhist temples in Thailand about the health benefits of eating vegan

- Partnered with Sinergia Animal Thailand to offer two cooking classes

- Launched a webpage for the DVA Thailand Project in English and Thai

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $27,000

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Provided 10 in-person, half-day presentations at Hanoi temples (prior to COVID-19 restrictions), where they focused on the health, ethical and environmental benefits of a vegan diet and provided a vegan buffet

- Offered a vegan cooking class to several hundred Buddhists at a Buddhist temple and adapted classes to transition online

- Planned a large vegan fest in Hanoi with a projected attendance of 45,000 (now on hold due to COVID-19 restrictions, but will go forward when safe to do so)

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $22,000

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Provided veterinary care including vaccines, spay/neuter, and treatment of conditions to 50 Buddhist temples through a volunteer vet team (an average visit provided care for 10 dogs, five cats, one cow, two rabbits, and one chicken)

- Often followed vet visits with talks about the importance of compassionate diet choices

- Gave children stethoscopes to listen to their heartbeat and then the heartbeat of a dog or cat; when asked if the hearts sounded the same, every child answered “yes”

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $22,000

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Helped influence a large Buddhist retreat center to serve 95% vegan food (after reportedly a decade of negotiations)

- Formed relationships with individual centers through volunteers who attended events and requested that centers increase plant-based meals

- Assembled a team of Buddhist teachers who wrote and signed a letter that is being sent to U.S. centers to open a dialogue on diet change

- Created a database of nearly 500 Buddhist centers in the U.S.

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $5,000

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Raised funds and recruited volunteers and new DVA members in Germany

- Led virtual mindfulness and meditation half-day retreats every month, reaching approximately 360 advocates

- Played DVA’s film, Animals and the Buddha, in Brazil with Portuguese subtitles and a large online audience

- Live streamed on Facebook about quality of life and Buddhist principles

- Utilized dog feeding events in Sri Lanka to provide emotional support to animal advocates

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $5,000

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Provided direct mentorship to the owner of a dog meat restaurant and convinced them to transition to a vegan menu

- Engaged with four other individuals to help each of them open veg*n23 restaurants in Hanoi and Hue

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $1,000

Our Assessment

Given their reported outputs and expenditures, we do not have concerns about the cost effectiveness of DVA’s diet change and legislation programs in Sri Lanka. However, the majority of the impacts of these programs are more indirect and/or may happen in the future; as such, we think that their cost effectiveness is more uncertain.

We have some concerns about the cost effectiveness of DVA’s veterinary care program in Sri Lanka. We do not think that veterinary care for companion animals is a high priority cause area because it is relatively less neglected. However, we believe DVA focuses on this program as a way to initially engage with monastics at Buddhist temples in order to develop further advocacy there.

As so few resources have gone into DVA’s diet change programs in Thailand and Vietnam, veterinary care program in Sri Lanka, restaurant owner mentorship program in Vietnam, diet change advocacy program in U.S. Buddhist centers, and worldwide chapters program, we are particularly uncertain about their cost effectiveness and thus have not included any further assessment.

Leadership and Culture

A charity that performs well on this criterion has strong leadership and a healthy organizational culture. The way an organization is led affects its organizational culture, which in turn impacts the organization’s effectiveness and stability.24 The key aspects that ACE considers when examining leadership and culture are reviewed in detail below.

Method

We review aspects of organizational leadership and culture by capturing staff and volunteer perspectives via our culture survey, in addition to information provided by top leadership staff (as defined by each charity).

Assessing leadership

First, we consider key information about the composition of leadership staff and board of directors. There appears to be no consensus in the literature on the specifics of the relationship between board composition and organizational performance,25 therefore we refrain from making judgements on board composition. However, because donors may have preferences on whether the Executive Director (ED) or other top executive staff are board members or not, we note when this is the case. According to the Council on Foundations,26 risks of EDs serving as board members include conflicts of interest when the board sets the ED’s salary, complicated reporting relationships, and blurred lines between governing bodies and staff. On the other hand, an ED that is part of a governing board can provide context about day-to-day operations and ultimately lead to better informed decisions, while also giving the ED more credibility and authority.27

We also consider information about leadership’s commitment to transparency by looking at available information on the charity’s website, such as key staff members, financial information, and board meeting notes. We require organizations selected for evaluation to be transparent with ACE throughout the process. Although we value transparency, we do not expect all organizations to be transparent with the public about sensitive information. For example, we recognize that organizations and individuals working in some regions or on some interventions could be harmed by making information about their work public. In these cases, we favor confidentiality over transparency.

In addition, we utilize our culture survey to ask staff to identify the extent to which they feel that leadership is competently guiding the organization.

Finally, there are specific considerations for charities that work internationally. For instance, “North–South” power imbalances—differences between more and less developed countries’ autonomy and decision-making abilities—can occur within the same organization or between organizations working in partnership. We think that it is important that charities, especially those from developed countries, prevent and address power imbalances by, for instance, creating opportunities for the national affiliates to influence decision-making at the international level, including “Southern” majorities in boards of governance.28 We ask leadership to elaborate on their approach and report measures they take.

Organizational policies

We ask organizations undergoing evaluation to provide a list of their human resources policies, and we elicit the views of staff and volunteers through our culture survey. Administering ACE’s culture survey to all staff members, as well as volunteers working at least 20 hours per month, is an eligibility requirement to be recommended as an ACE Top or Standout Charity. However, ACE does not require individual staff members or volunteers at participating charities to complete the survey. We recognize that surveying staff and volunteers could (i) lead to inaccuracies due to selection bias, and (ii) may not reflect employees’ true opinions as they are aware that their responses could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer. In our experience, it is easier to uncover issues with an organization’s culture than it is to assess how strong an organization’s culture is. Therefore, we focus on determining whether there are issues in the organization’s culture that have a negative impact on staff productivity and well-being.

We assume that employees in the nonprofit sector have incentives that are material, purposive, and solidary.29 Since nonprofit sector wages are typically below for-profit wages, our survey elicits wage satisfaction from all staff. Additionally, we request the organization’s benefit policies regarding time off, health care, and training and professional development. As policies vary across countries and cultures, we do not evaluate charities based on their set of policies and do not expect effective charities to have all policies in place.

To capture whether the organization also provides non-material incentives, e.g., goal-related intangible rewards, we elicit employee engagement using the Gallup Q12 survey. We consider an average engagement score below the median value (i.e., below four) of the scale a potential concern.

ACE believes that the animal advocacy movement should be safe and inclusive for everyone. Therefore, we also collect information about policies and activities regarding representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI). We use the terms “representation” and “diversity” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of certain social identity characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries).30 Additionally, we believe that effective charities must have human resources policies against harassment31 and discrimination,32 and that cases of harrassment and discrimination in the workplace should be addressed appropriately. If a specific case of harassment or discrimination from the last 12 months is reported to ACE by several current or former staff members or volunteers at a charity, and said case remains unaddressed, the charity in question is ineligible to receive a recommendation from ACE.

Information and Analysis

Leadership staff

In this section, we list each charity’s President (or equivalent) and/or Executive Director (or equivalent), and we describe the board of directors. This is completed for the purpose of transparency and to identify the relationship between the ED and board of directors.

- President: Bob Isaacson, involved in the organization for 10 years

- Number of members on board: 3 members, including President Bob Isaacson

DVA did not have a transition in leadership in the last year.

All of the staff respondents to our culture survey at least somewhat agreed that DVA’s leadership team guides the organization competently.

DVA has been transparent with ACE during the evaluation process. In addition, DVA’s audited financial documents (including the most recently filed IRS form 990 for U.S. organizations) are available on GuideStar. A list of key staff members is available on the charity’s website. A list of board members is not available on the charity’s website.

DVA’s has expanded from the U.S. to Australia, Brazil, England, Finland, Germany, Malaysia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand. DVA’s local teams contribute to decision making for local programs carried out by the subsidiaries. In order to prevent and address potential power imbalances between developed and developing country parties, DVA has a ‘cultural advisor’ for each developing region to facilitate communication and understanding and to encourage open discussion of national histories of oppression.

Culture

DVA has eight staff members (including full-time, part-time, and contractors) and two volunteers. Eight staff members and one volunteer responded to our survey, yielding response rates of 100% and 50%, respectively. DVA has a very small team—at least one of the eight team members were identified as members of leadership—which could have skewed the results of our survey.

DVA does not have a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. DVA let us know that they offer a discretionary time off (DTO) plan that provides flexible vacation days paid at the employee’s current base salary. They do not offer health coverage. None of the staff that responded to our survey report that they are dissatisfied with their wage or the benefits provided. Additional policies are listed in the table below.

General compensation policies

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A formal compensation policy to determine staff salaries | |

| Paid time off | |

| Sick days and personal leave | |

| Healthcare coverage | |

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| Annual (or more frequent) performance evaluations | |

| Formal onboarding or orientation process | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support | |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Remote work option | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) |

The average score in our engagement survey is 6.6 (on a 1–7 scale), suggesting that on average, staff do not exhibit a low engagement score. DVA does not have staff policies against harassment and discrimination. None of the staff or volunteers report to have experienced or witnessed harassment or discrimination at their workplace during the last twelve months. See all other related policies in the table below.

Policies related to representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI)

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics/conduct | |

| A written statement that the organization does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels, up to and including the board of directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| Documentation of all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

Our Assessment

We did not detect any major concerns in DVA’s leadership and organizational culture. We positively noted that DVA’s staff generally agree that leadership guides the organization competently, that team members do not experience harrassment or discrimination in the workplace, and that team members seem generally engaged and satisfied with their job. We think that DVA could benefit from creating staff policies against harassment and discrimination.

On average, our team considers advocating for welfare improvements to be a positive and promising approach. However, there are different viewpoints within ACE’s research team on the effect of advocating for animal welfare standards on the spread of anti-speciesist values. There are concerns that arguing for welfare improvements may lead to complacency related to animal welfare and give the public an inconsistent message—e.g., see Wrenn (2012). In addition, there are concerns with the alliance between nonprofit organizations and the companies that are directly responsible for animal exploitation, as explored in Baur and Schmitz (2012).

The weightings used for calculating these country scores are scale (25%), tractability (55%), and regional influence (20%).

For arguments supporting the view that the most important consideration of our present actions should be their impact in the long term, see Greaves & MacAskill (2019) and Beckstead (2019).

DVA reports that the FAOI scores potentially understate the importance of the 140 million Buddhists living in Thailand, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka. They also note that consumption of fishes is relatively high in these Buddhist majority countries.

See Bianchi et al. (2018a) for a summary of this literature.

See, for example, Animal Charity Evaluators (2016a), Tiplady, Walsh, & Phillips (2013), and Tonsor & Olynk (2011).

To be selected for evaluation, we require that a charity has a revenue of at least about $50,000 and faces no country-specific regulatory barriers to receiving money from ACE.

DVA received Movement Grants of $15,000 in April 2019 and of $40,000 in June 2021.

DVA notes they received $75,000 in 2020 and $75,000 in 2021 from Open Philanthropy, restricted to expenses related to the Sri Lankan Animal Welfare Act. Including the $40,000 grant from Movement Grants and a $130,000 donation match, this significantly increased DVA’s funding in 2021.

DVA reports that they have recently decided to hire a part-time Director for their U.S. Buddhist centers project and they are in the interview process.

A negative amount for change in expenditure here means that the reported difference in program costs between 2022 and 2021 is larger than the total change in expenditure. See the RFMF sheet for details.

DVA estimates these additional expansions add up to $551,000.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness.

DVA reports that these restaurants do not serve fish or eggs, but they sometimes use butter, cream, or milk in small quantities for cooking.

Clark and Wilson (1961), as cited in Rollag (n.d.)

Examples of such social identity characteristics are: race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, and genetic information.

Harassment can be non-sexual or sexual in nature: ACE defines non-sexual harassment as unwelcome conduct—including physical, verbal, and nonverbal behavior—that upsets, demeans, humiliates, intimidates, or threatens an individual or group. Harassment may occur in one incident or many. ACE defines sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances; requests for sexual favors; and other physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors of a sexual nature when (i) submission to such conduct is made explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment; (ii) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting the targeted individual; or (iii) such conduct has the purpose or effect of interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

ACE defines discrimination as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of or hostility toward an individual on the basis of certain characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries), such as race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, or genetic information.