The Good Food Institute

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2021 |

| Current Version | 2022 |

Archived Version: November, 2021

What does GFI do?

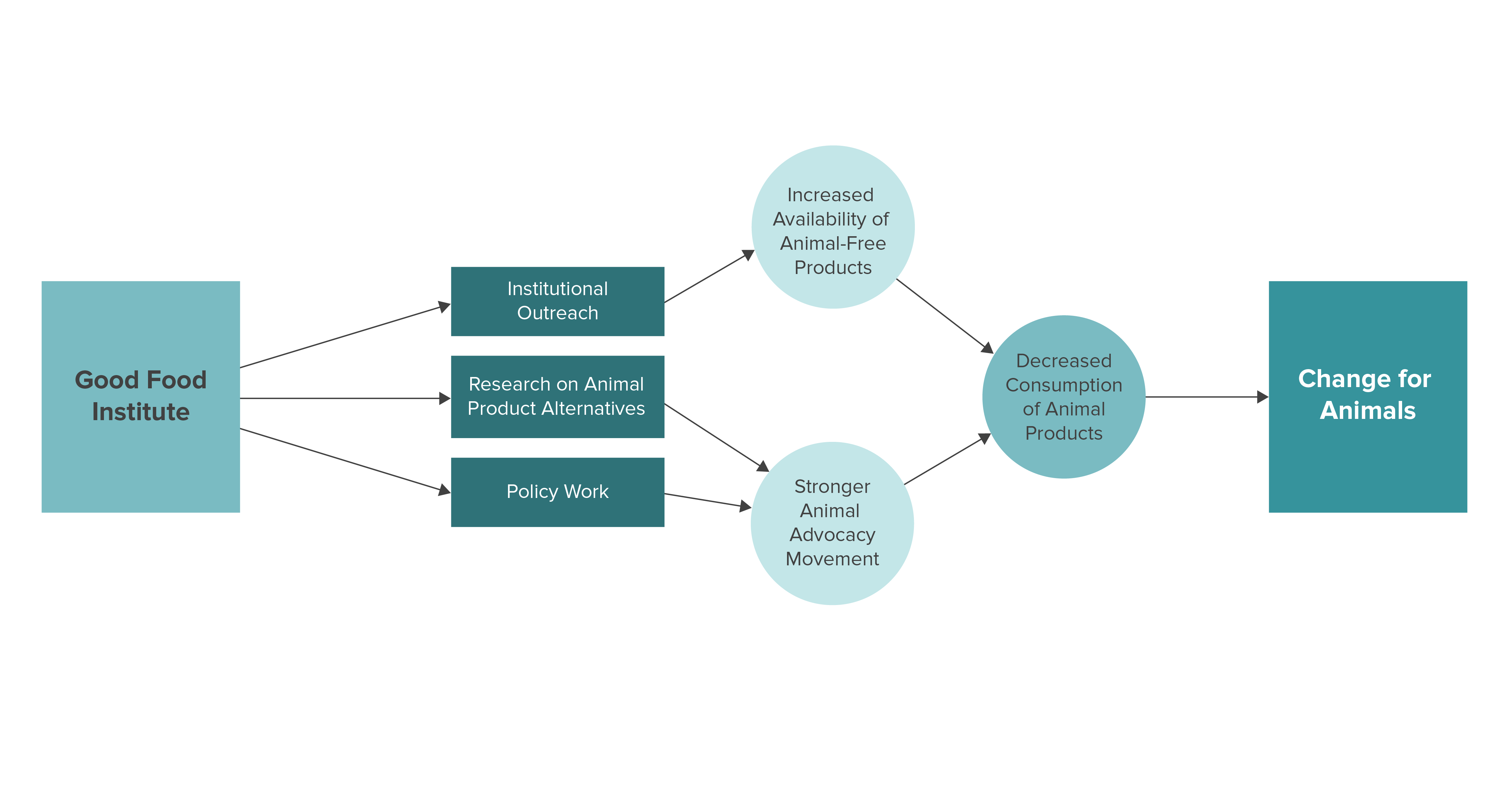

The Good Food Institute (GFI) was founded in 2016. GFI currently operates in the U.S., Brazil, India, Hong Kong, Singapore, Europe, and Israel, where they work to increase the availability of animal-free products through supporting the development and marketing of plant-based and cell-cultured alternatives to animal products. They achieve this through corporate engagement, institutional outreach, and policy work. They also support research and start-ups focused on alternative proteins, which strengthens the capacity of the animal advocacy movement.

What are their strengths?

We think that interventions used by GFI—scientific research, corporate engagement and policy work—are highly effective in strengthening the animal advocacy movement and increasing the availability of animal-free products. We also think their work promoting research on alternative proteins and building a community for those working in the industry are highly effective in strengthening the animal advocacy movement. In addition, we think that GFI’s work in the U.S., Brazil, India, and Asia Pacific is particularly effective based on high tractability and high numbers of animals in those countries.

What are their weaknesses?

We think that GFI’s focus on cell-cultured products could have an enormous impact for farmed animals in the longer term, as cell-cultured food potentially cause a considerable decrease in demand for farmed animal products. However, we are relatively uncertain about the price-competitiveness of cell-cultured products with conventional animal protein. Furthermore, the majority of impacts that GFI’s work has on animals are more indirect and may happen in the future. As such, the cost effectiveness of their work is more difficult to assess using our methods. We also have concerns about some reports of alleged retaliation by GFI’s top leadership toward current and former staff. We think that GFI could benefit from having an independent board. GFI has provided a detailed response to our assessment of their leadership and culture.

Programs

A charity that performs well on this criterion has programs that we expect are highly effective in reducing the suffering of animals. The key aspects that ACE considers when examining a charity’s programs are reviewed in detail below.

Method

In this criterion, we assess the effectiveness of each of the charity’s programs by analyzing (i) the interventions each program uses, (ii) the outcomes those interventions work toward, (iii) the countries in which the program takes place, and (iv) the groups of animals the program affects. We use information supplied by the charity to provide a more detailed analysis of each of these four factors. Our assessment of each intervention is informed by our research briefs and other relevant research.

At the beginning of our evaluation process, we select charities that we believe have the most effective programs. This year, we considered a comprehensive list of animal advocacy charities that focus on improving the lives of farmed or wild animals. We selected farmed animal charities based on the outcomes they work toward, the regions they work in, and the specific animal group(s) their programs target. We don’t currently consider animal group(s) targeted as part of our evaluation for wild animal charities, as the number of charities working on the welfare of wild animals is very small.

Outcomes

We categorize the work of animal advocacy charities by their outcomes, broadly distinguishing whether interventions focus on individual or institutional change. Individual-focused interventions often involve decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Institutional change involves improving animal welfare standards, increasing the availability of animal-free products, or strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

We believe that changing individual habits and beliefs is difficult to achieve through individual outreach. Currently, we find the arguments for an institution-focused approach1 more compelling than individual-focused approaches. We believe that raising welfare standards increases animal welfare for a large number of animals in the short term2 and may contribute to transforming markets in the long run.3 Increasing the availability of animal-free foods, e.g., by bringing new, affordable products to the market or providing more plant-based menu options, can provide a convenient opportunity for people to choose more plant-based options. Moreover, we believe that efforts to strengthen the animal advocacy movement, e.g., by improving organizational effectiveness and building alliances, can support all other outcomes and may be relatively neglected.

Therefore, when considering charities to evaluate, we prioritize those that work to improve welfare standards, increase the availability of animal-free products, or strengthen the animal advocacy movement. We give lower priority to charities that focus on decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Charities selected for evaluation are sent a request for more in-depth information about their programs and the specific interventions they use. We then present and assess each of the charities’ programs. In line with our commitment to following empirical evidence and logical reasoning, we use existing research to inform our assessments and explain our thinking about the effectiveness of different interventions.

Countries

A charity’s countries and regions of operations can affect their work with regard to scale, neglectedness, and tractability. We prioritize charities in countries with relatively large animal agricultural industries, few other charities engaged in similar work, and in which animal advocacy is likely to be feasible and have a lasting impact. In our charity selection process, we used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI), which combines proxies for scale, tractability, and global influence to create country scores.4 To assess neglectedness, we used our own data on the number of organizations that we are aware of working in each country. Below we present these measures for the countries that GFI operates in.

A note about long-term impact

Each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.5 The potential number of animals affected increases over time due to population growth and an accumulation of generations. Thus, we would expect that the long-term impacts of an action would likely affect more animals than the short-term impacts of the same action. Nevertheless, we are highly uncertain about the particular long-term effects of each intervention. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew toward overemphasizing short-term effects.

Information and Analysis

Cause areas

GFI’s programs focus exclusively on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we think is a high-priority cause area.

Countries

GFI develops their programs in the U.S., Brazil, the E.U. (based in Belgium), India, Israel, and Asia Pacific (based in Singapore). Their headquarters are in the U.S.

We used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI) with the suggested weightings of scale (25%), tractability, (55%) and influence (20%) to determine each country’s total FAOI score. We report this score along with the country’s global ranking from a total of 60 countries in the following format: FAOI score(global ranking). The U.S., Brazil, India, and Singapore have the following scores and rankings, respectively: 53.92(2), 32.87(5), 33.42(4), and 9.85(43). The FAOI does not include Israel or the E.U. However, it does include 28 European countries that range from an FAOI score of 1.45 (Latvia) to 33.52 (Germany). According to the comprehensive list of charities we are aware of, there are about 724 farmed animal advocacy organizations, excluding sanctuaries, worldwide. From this list, we found 220 in the U.S., 15 in Brazil, 20 in India, 12 in Israel, and 5 in Singapore. We believe that farmed animal advocacy in India is relatively neglected, given its large scale and small number of charities operating in the country. We also believe that farmed animal advocacy in the U.S., Brazil, and India are especially high-priority because of their high FAOI scores.

Description of programs

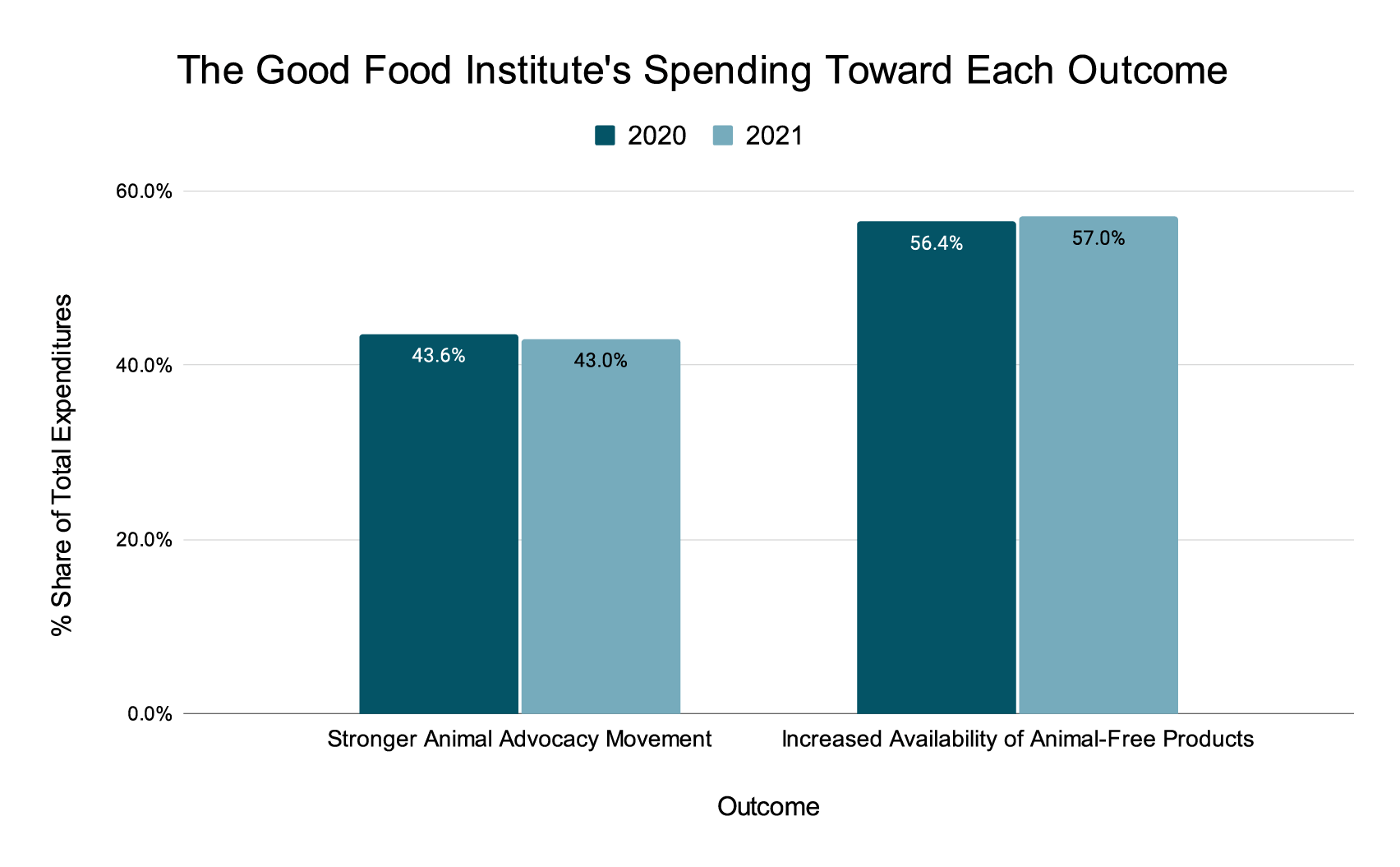

GFI pursues different avenues for creating change for animals. Their work focuses on increasing the availability of animal-free products and strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

Below, we describe each of GFI’s programs, listed in order of the financial resources devoted to them in 2020 (from highest to lowest). We list major accomplishments for each program, if a track record is available.

GFI’s programs

This program focuses on conducting original scientific research and supporting external scientific research—through funding, directories, repositories, databases, seminars, and workshops—to accelerate the production and commercialization of alternative proteins.

Main interventions

- Research

- Technical resources

- Events

Key historical accomplishments

- Launched a research grant program, giving nearly $7 million toward the first two cohorts of grantees (2019–2020)

- Created technical resources (e.g., the Cultivated Meat Research Tools Directory, the Kerafast cell line repository, and the Atlas and PISCES database) and resources to support researchers (e.g., a scientific research database, a collaborative research directory, and a research funding database)

- Published 11 scientific papers and white papers on alternative proteins (2017–2020)

- Supported faculty members of at least 6 U.S. universities in the development of courses on animal product alternatives (2017–2021)

- Hosted a monthly online seminar series, and launched a Massive Open Online Course, reaching over 6000 enrollments (2021)

Main interventions

- Institutional outreach

- Publications

Key historical accomplishments

- Published industry reports for cell-cultured and plant-based products, the “Good Food Retail Report” (2020), and the annual “Good Food Restaurant Scorecard” (2017–2019)

- Launched GFIdeas Community and a directory of food entrepreneurs (2016)

- Published a directory of co-manufacturers and service providers, a company database, a guide for startups, a map of incubators, and the Sustainable Seafood Initiative Newsletter

- Engaged large food companies regarding plant-based and cell-cultured meat product innovation and/or investments

- Hosted three editions of the Good Food Conference (2018–2021)

- Co-launched two venture capital funds (2015–2017)

- Co-founded and launched three alternative protein companies (2016–2018)

Main interventions

- Resources

- Support and advice

Key historical accomplishments

- Co-launched Dao Foods, a company that helps entrepreneurs introduce alternative protein products in China (2019)

- Co-created The Good Food Startup Manual: Hong Kong Edition and Singapore Edition, and published the “China Plant-based Meat Industry Report” (2018)

- Organized the Asia Summit on Alternative Protein (2020)

- Launched a course on alternative proteins in Singapore, which was covered in The Straits Times, Lianhe Zaobao, and a radio program (2021)

- Published the “Asian Cropportunities: Supplying Raw Materials for Plant-Based Meat” report (2020) and received coverage in top regional media, including the South China Morning Post, The Bangkok Post, Myanmar Times, and VnExpress

- Counseled the Singapore government, the first government to approve cultivated meat sales (2020)

Main interventions

- Influencing funding

- Outreach

- Support and advice

Key historical accomplishments

- Co-hosted the Future of Protein Summit (2018) and the Smart Protein Summit (2020)

- Partnered with Institute of Chemical Technology, Mumbai to establish the Centre of Excellence in Cellular Agriculture, a government-sponsored research center focused entirely on cultivated meat (2019)

- Launched the Smart Protein Innovation Challenge (2021)

- Advised dozens of entrepreneurs on early-stage steps in plant-based meat startups, including helping a Bollywood celebrity couple launch their own startup

Main interventions

- Government engagement

- Lawsuits

Key historical accomplishments

- With collaboration from others, defeated a bill that threatened to overrule a USDA and FDA commitment to a cooperative regulatory framework for cell-cultured meat, and submitted comments to influence U.S. regulatory framework for cell-cultured meat (2018)

- Successfully lobbied to shape the language of a spending bill report that influenced the USDA to invest in research on plant proteins (2017–2018)

- Filed a lawsuit, together with ALDF and ACLU, against a meat labeling law in Missouri (2018)

- In cooperation with other groups, opposed label censorship in 26 states (was successful in 14 of them)

- In conjunction with other groups, submitted public comments in favor of blocking a rider to the Agriculture Appropriations Bill that would have given the USDA jurisdiction over cell-cultured animal products

Main interventions

- Outreach

- Support and advice

Key historical accomplishments

- Launched The Good Food Start Up Manual – Israel Edition (2020) and the “Israel State of Alternative Protein Innovation Report” (2021)

- Published the Israel Alternative Protein Academic Database (2020)

- Developed an alternative protein academic course for undergraduate and graduate students at three universities in Israel (2020)

Main interventions

- Influencing funding

- Outreach

Key historical accomplishments

- Helped generate an article and an editorial in the New Scientist (2020)

- Received coverage from the BBC and Euronews (2019)

- Successfully lobbied the European Commission to make alternative proteins a focus area in the R&D section of its Farm-to-Fork Strategy

- Played a contributing role, along with other organizations, in defeating the E.U.-wide ‘veggie burger ban’ proposal, which would have censored meat-related descriptors for plant-based products in all 27 E.U. countries and expanded E.U. dairy labeling proscriptions

Main interventions

- Outreach

- Support and advice

Key historical accomplishments

- Influenced egg company Grupo Mantiqueira to launch a plant-based egg (2019)

- Influenced new company Fazenda Futuro to create plant-based burger (2019)

- Secured 500,000 BRL (~$100,000 USD) from the government for plant-based meat research

- Signed a cooperation agreement with the government of the State of Amazonas to promote alternative proteins as a sustainable economic alternative use of theforest’s biodiversity (2019)

- Hosted a workshop, “Opportunities for the Development of Alternative Proteins in the State of Amazonas”, for 50 researchers from local universities (2020)

Research for intervention effectiveness

Supporting and conducting research on plant-based alternatives

We generally believe that increasing the availability of plant-based food options will decrease the consumption of animal products. However, the body of empirical research focused on answering this question is limited to just a few field experiments. Estimates on how the availability of plant-based alternatives (of equivalent price, taste, texture and nutrition to conventional meat) would decrease animal product consumption vary widely, ranging from 2.4%6 to 66%7. We expect the marginal impact of introducing one more plant-based alternative at price parity and at or near taste, texture and nutrition parity in a food service or supermarket setting to be towards the lower end of this range.

Supporting and conducting research on cell-cultured alternatives

Although research is still required to optimize cell culture methodology—and consumer acceptance of cell-cultured food products could still increase—we expect that cell-cultured food is likely to cause a considerable decrease in demand for farmed animal products if it reaches price-competitiveness with conventional animal protein. In the long term, this reduced demand for animal-based products could weaken the animal agriculture industry.8

Institutional outreach

Currently, there is no peer-reviewed research specifically about institutional outreach to influence the availability of animal-free products. However, we could learn from studies that investigate the effectiveness of outreach to hospitals and schools on increasing the availability of “healthy foods” (specifically fruits, vegetables, and whole grains). We believe that reaching out to nonprofit institutions with the effective strategies identified in these studies has the potential to increase the availability of animal-free foods, based on high participation and success rates in health food outreach to schools and hospitals. Some of these strategies included i) working with the local hospital association and hospital workers’ unions to encourage participation, ii) enlisting in-depth assistance from dietitians, and iii) providing advice on how to incorporate new standards into existing operations. However, due to concerns about the generalizability of this intervention to outreach for animal-free foods, we believe that more research is needed.

Policy work

GFI engages with governments and files lawsuits with the goal of bringing plant-based and cell-cultured meat to market. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects would be particularly long-lasting.

Our Assessment

We think that GFI’s science and technology and corporate engagement programs—aimed at strengthening the animal advocacy movement and increasing the availability of animal-free products—are particularly effective, but there is little evidence supporting this claim.

We consider GFI’s work in the U.S., Brazil, India, and Asia Pacific to be particularly effective based on the high numbers of animals and high tractability in these areas.

Overall, we think that almost all of GFI’s spending on programs goes toward outcomes and countries that we think are a high priority.

Room For More Funding

A new recommendation from ACE could lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding. In this criterion, we investigate whether a charity is able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in or, if the charity has a prior recommendation status, whether they will continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation.

Method

In the following section, we inspect the charity’s plans for expansion as well as their financials, including revenue and expenditure projections.

The charities we evaluate typically receive revenue from a variety of different sources, such as individual donations or grants from foundations.9 In order to guarantee that a charity will raise the funds needed for their operations, they should be able to predict changes in future revenue. To estimate charities’ room for more funding, we request records of their revenue since 2019 and ask what they predict their revenue will be in 2021–2023. A review of the literature on nonprofit finance suggests that revenue diversity may be positively associated with revenue predictability if the sources of income are largely uncorrelated.10 However, a few sources of large donations—if stable and reliable—may also be associated with high performance and growth. Therefore, in this criterion, we also indicate the charities’ major sources of income.

We present the charities’ reported plans for expansion of each program as well as other planned changes for the next two years. We do not make active suggestions for additional plans. However, we ask charities to indicate how they would spend additional funding that we expect would come in as a result of a new recommendation from ACE, considering that a Standout Charity status and a Top Charity status would likely lead to a $100,000 or $1,000,000 increase in funding, respectively. Note that we list the expenditures for planned non-program expenses but do not make any assessment of the charity’s overhead costs in this criterion, given that there is no evidence that the total share of overhead costs is negatively related to overall effectiveness.11 However, we do consider relative overhead costs per program in our Cost-Effectiveness criterion. Here we focus on evaluating whether additional resources are likely to be used for effective programs or other beneficial changes in the organization. The latter may include investments into infrastructure and efforts to retain staff, both of which we think are important for sustainable growth.

It is common practice for charities to hold more funds than needed for their current expenses (i.e., reserves) in order to be able to withstand changes in the business cycle or other external shocks that may affect their incoming revenue. Such additional funds can also serve as investments into future projects in the long run. Thus, it can be effective to provide a charity with additional funds to secure the stability of the organization or provide funding for larger, future projects. We do not prescribe a certain share of reserves, but we suggest that charities hold reserves equal to at least one year of expenditures, and we increase a charity’s room for more funding if their reserves in 2021 are less than 100% of their total expenditure.

Finally, we aggregate the financial information and the charity’s plans to form an assessment of their room for more funding. All descriptive data and estimations can be found in this sheet. Our assessment of a charity’s ability to effectively absorb additional funding helps inform our recommendation decision.

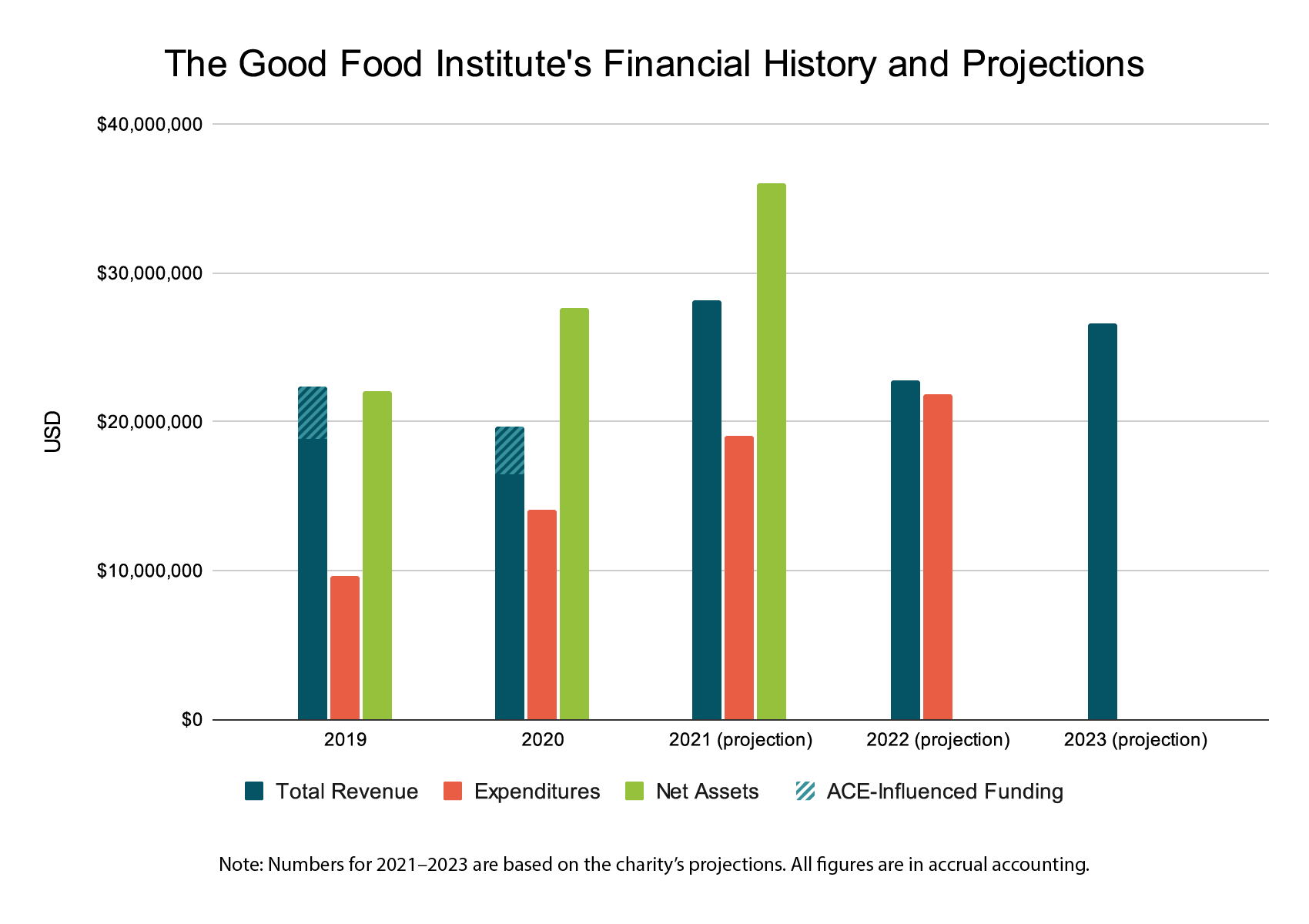

Information and Analysis

The chart below shows GFI’s revenues, expenditures, and net assets from 2019–2020, as well as projections for the years 2021–2023.12 The information is based on the charity’s past financial data and their own predictions for the years 2021–2023.

GFI receives the majority of their income from donations, 0.33% from their work, and 0.74% from capital investments.13 They expect their revenue to increase more in 2021 than in the year before due to their large fundraising goals.

GFI has also received funding influenced by ACE as a result of their recommended charity status, which they have held for the past five years. As such, their room for more funding analysis will focus on our assessment of whether they will continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation.

According to GFI’s reported projections, their estimated revenue in 2022 will sufficiently cover their expenditures.14 However, we estimate that GFI has received $3,508,00015 in 2019 and $3,191,000 in 2020 as a result of their prior recommended charity status. Should GFI lose their recommended charity status, their projected revenue may be lowered, resulting in more room for funding.

With more than 100% of their current annual expenditures held in net assets—as projected by GFI for 2021—we believe that they hold a sufficient amount of reserves.

Below we list GFI’s plans for expansion for each program as well as other planned expenditures, such as administrative costs, wages, and training. We do not verify the feasibility of the plans or the specifics of how changes in expenditure will cover planned expansions. Reported changes in expenditure are based on GFI’s own estimates of changes in program expenditures for 2021–2022 and 2022–2023.

GFI plans to expand their science and technology, corporate engagement, and policy programs, as well as GFI Asia Pacific (APAC), GFI India, GFI Israel, GFI Europe and GFI Brazil. GFI also plans to: establish a presence in Korea, Japan, and seven European countries; start one potential spin off project in investment consulting and an entrepreneur in residence program; and launch an alternative protein research institute. More details can be found in the corresponding estimation sheet and the supplementary materials. Readers may also consult GFI’s strategic plan.

- Hire four new team members in 2021

- Hire six new team members in 2022

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $1,078,000

- 2023: $700,000

- Hire three new team members in 2021 and four in 2022. Positions include a General Outreach Specialist, a Consumer Insights and Research Specialist, an ESG/CSR Analyst, and a Supply Chain Specialist.

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $770,000

- 2023: $500,000

- Expand to Japan and South Korea, hiring six to eight team members at each organization

- Hire an executive team, including Directors of SciTech, Policy, Corporate Engagement, and Operations

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $1,555,000

- 2023: $1,870,000

- Hire two new team members in 2021 and five in 2022. Positions include Federal Executive Advocacy Manager, a University Funding Advocate, a Senior Fellow, and a Policy Specialist/Counsel.

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $1,155,000

- 2023: $750,000

- Hire a SciTech Director, a Food Engineer, an Infrastructure Engineer, and White Space Project Managers

- Launch three centerns to scale alternative protein production and to support the creation of 30 research labs

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $320,000

- 2023: $464,000

- Hire policy leads in Spain, Italy, Germany, and Scandinavia in 2022

- Hire a new team member in Switzerland in 2023

- Hire a SciTech Specialist, a Research Analyst, and a Communications Officer

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $1,151,000

- 2023: $1,262,000

- Hire a Technical Regulatory Specialist, Policy Analysts, and a SciTech Fermentation Specialist

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $506,000

- 2023: $477,000

- Establish a presence in Korea, Japan, and seven European countries

- Potentially launch or spin off project in investment consulting and research

- Potentially launch or spin off project of Entrepreneur in Residence program

- Potentially launch an alt-protein research institute

- Hire a U.S.-based President

Reported change in expenditure

Our Assessment

GFI plans to focus future expansions on their science and technology, corporate engagement, and policy programs, as well as several potential new programs. GFI also plans to expand GFI Asia Pacific, GFI India, GFI Israel, GFI Europe, and GFI Brazil. For donors influenced by ACE wishing to donate to GFI, we estimate that the organization can continue to effectively absorb funding that we expect to come with a recommendation status.

Based on i) GFI’s own projections that their projected revenue will cover their expenditures, ii) our assessment that they have sufficient reserves, and iii) our assumption that a loss of recommendation status would result in a decrease in funding, we believe that overall, GFI continues to have room for $2,424,000 of additional funding in 2022. See our Programs criterion for our assessment of the effectiveness of their programs.

It is possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or that they could come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. If a charity receives a recommendation as Top Charity, we check in mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented below to indicate whether we still expect them to be able to effectively absorb additional funding at that time.

Cost Effectiveness

Method

A charity’s recent cost effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component in understanding how cost effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources over the past 18 months and compare that to the outputs they have achieved in each of their main programs during that time. We seek to understand whether each charity has been successful at implementing their programs in the recent past and whether past successes were achieved at a reasonable cost. We only complete an assessment of cost effectiveness for programs that started in 2019 or earlier and that have expenditures totaling at least 10% of the organization’s annual budget.

Below, we report what we believe to be the key outputs of each program, as well as the total program expenditures. To estimate total program expenditures, we take the reported expenditures for each program and add a portion of their non-program expenditures weighted by the size of the program. This allows us to incorporate general organizational running costs into our consideration of cost effectiveness.

We spend a significant portion of our time during the evaluation process verifying the outputs charities report to us. We do this by (i) searching for independent sources that can help us verify claims, and (ii) directing follow-up questions to charities to gather more information. We adjusted some of the reported claims based on our verification work.

Information and Analysis

Overview of expenditures

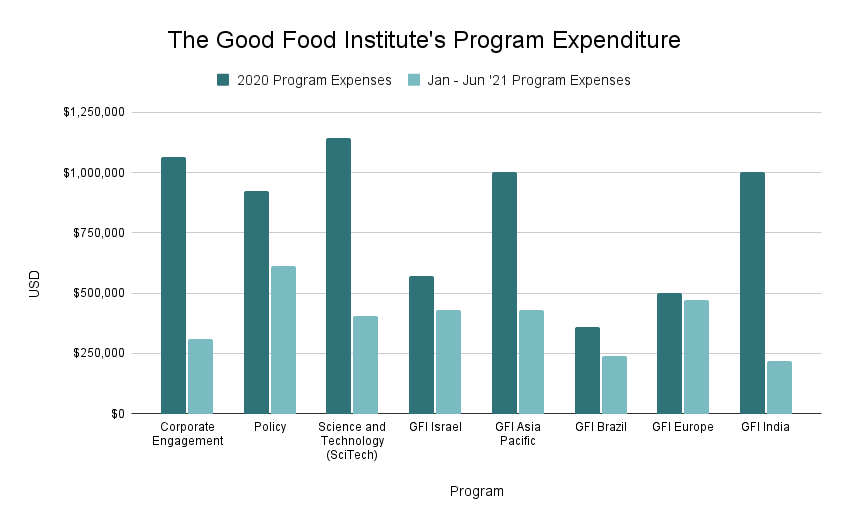

The following chart shows the GFI’s total program expenditures from January 2020 – June 2021.

- Hosted webinars on cultivated meat with 563 attendees

- Co-authored a paper titled “The Business of Cultured Meat" that was published in June 2020 and selected as the cover story for Trends in Biotechnology

- Maintained a number of research directories, including the Cultivated Meat Research Tools Directory, Kerafast cell line repository (an initiative to make proven cell lines accessible to researchers), and PISCES (a resource to help alternative seafood researchers and companies)

- Hosted a massive open online course (MOOC), which has grown from 3,000 attendees in early 2020 to more than 6,000 as of June 2021

- Helped launch nine alternative protein courses at U.S. academic institutions and engaged 177 faculty members in building alternative protein courses (alone and in cooperation with other groups)

Expenditures19 (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $3,035,000

GFI’s science and technology program focuses on accelerating and promoting the commercialization of alternatives to animal products.

- Helped one of the largest meat producers develop three new plant-based products

- Created resources for scientists, students, startups, investors, and industry stakeholders, including a talent database and a community database

- Published the “Good Food Retail Report" (2020), which benchmarks the top 15 U.S. grocery retailers on plant-based sales strategies

- Strengthened existing relationships with retailers and built new relationships with six major U.S. retailers

- Published “State of the Industry" reports for cultivated meat, fermentation, and plant-based meat, eggs, and dairy.

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $2,701,000

GFI’s corporate engagement program focuses on increasing the availability of animal free-products by enabling food industry partners to develop and bring alternative protein products to market. They primarily do this by producing industry reports, organizing monthly newsletters, and working with companies across the global alternative protein industry to drive investment, accelerate innovation, and scale the supply chain. The majority of their results are indirect, and as such, it is difficult to assess their cost effectiveness.

- Organized the inaugural two-day Asia Summit on Alternative Protein, the first-ever virtual summit on alternative proteins with a pan-Asian focus, with over 1,500 registrants from over 50 countries

- Coordinated the the first alternative protein university course in the Asia Pacific region at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore

- Co-launched the innovation challenge, “Next-Gen Cropportunities", in collaboration with the youth-focused global solutions network Thought for Food. The winning team submitted a proposal to expand opportunities for smallholder farmers in the plant-based food sector.

- Co-hosted a two-day workshop on regulations for alternative proteins, in collaboration with GFI Brazil and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Regional Office for the Western Pacific, which was attended by dozens of WHO staff and government representatives from 13 countries

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $2,806,000

- Launched the Smart Innovation Challenge to encourage alternative protein innovation for students, researchers, and entrepreneurs. Over 1,000 people attended and several plant-based food companies were launched or incubated during the challenge (including Brew51 and Seaspire).

- Curated and led the five-day virtual event Smart Protein Summit, hosting 1,500 attendees and 80 speakers

- Initiated a Memorandum of Understanding with the Government of India’s Council of Scientific and Industrial Research to advance the alternative protein sector in India

- Hosted a workshop on investment opportunities within the alternative protein sector with more than 25 investors, including India’s top two investment firms (Omnivore Partners and Accel Partners)

- Advised dozens of entrepreneurs on early-stage steps in plant-based meat start-ups, including Imagine Meats

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $1,872,000

- Lobbied the House Appropriations committee to include language encouraging $5 million in alternative protein research funding for the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in the draft fiscal year 2022 USDA funding bill

- Played a contributing role in defeating three label censorship laws

- Organized and drafted a letter from 20 members of the U.S. House of Representatives asking the House Appropriations Committee to allocate $50 million for the USDA and $50 million for the National Science Foundation to support alternative protein research

- Breakthrough Energy (a coalition of organizations that aim to accelerate innovation in sustainable energy and other technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, spearheaded by Bill Gates) incorporated GFI’s policy recommendations into their new federal climate policy, positioning alternative meat as a critical component of reaching net-zero emissions

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $3,017,000

In legal and political advocacy, we think it is likely that the most cost-effective work is focused on system-wide change that, although harder to secure, has the potential to affect a larger number of animals. GFI’s policy program is focused on work of this nature. The majority of their results are indirect, and as such, it is difficult to assess their cost effectiveness.

- GFI Israel’s Managing Director met with the Israeli Prime Minister to discuss alternative protein technologies and the impact of animal food production on the environment

- Organized the “Alternative Protein Leaders Meetup" for more than 200 attendees from the Israeli industry, academic, and policy sectors

- In collaboration with GFI’s U.S. branch, facilitated a partnership agreement with Nestlé Foods and Future Meat (an Israeli cultivated meat company), receiving coverage in Food Navigator, Food Dive, and Food Manufacture

- Co-authored a study on cultivated meat that was published in Nature Food

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $1,969,000

- Successfully lobbied the European Commission to make alternative proteins a focus area in the R&D section of its Farm-to-Fork Strategy

- Played a contributing role in defeating the E.U.-wide ‘veggie burger ban’ proposal, which would have censored meat-related descriptors for plant-based products in all 27 E.U. countries and expanded E.U. dairy labeling proscriptions

- Co-founded the European Alliance for Plant-based Foods (EAPF) and played a contributing role in convincing them to work on public R&D funding for plant-based foods

- Engaged the U.K.’s National Food Strategy Team to influence recommendations of a national food policy plan, resulting in the UK spending £50 million to help fund a support entrepreneurship in alternative proteins and allocating £75 million to invest in alternative protein research

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $1,903,000

- Launched the “Biomas Project", a research grant focused on transforming plant products native to the Amazon and Cerrado biomes into food ingredients for the alternative protein industry

- Collaborated with the state government of Amazonas to develop its bioeconomy agenda and co-hosted a workshop, “Opportunities for the Development of Alternative Proteins in the State of Amazonas", for 50 researchers from local universities

- Created and led the first alternative protein working group within the Brazilian Bio-Innovation Association (ABBI)

- Organized a workshop with the participation of more than 60 Brazilian regulators from the Ministry of Agriculture and National Health Agency focused on the production process and regulation of cell culture technology

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $1,173,000

Our Assessment

The majority of impacts that GFI’s program outputs have on animals are relatively indirect and may happen in the future. As such, the cost effectiveness of their work is more difficult to assess using our methods. Given the reported outputs and expenditures, we do not have concerns about the cost effectiveness of the GFI’s programs.

Leadership and Culture

A charity that performs well on this criterion has strong leadership and a healthy organizational culture. The way an organization is led affects its organizational culture, which in turn impacts the organization’s effectiveness and stability.20 The key aspects that ACE considers when examining leadership and culture are reviewed in detail below.

Method

We review aspects of organizational leadership and culture by capturing staff and volunteer perspectives via our culture survey, in addition to information provided by top leadership staff (as defined by each charity).

Assessing leadership

First, we consider key information about the composition of leadership staff and board of directors. There appears to be no consensus in the literature on the specifics of the relationship between board composition and organizational performance,21 therefore we refrain from making judgements on board composition. However, because donors may have preferences on whether the Executive Director (ED) or other top executive staff are board members or not, we note when this is the case. According to the Council on Foundations,22 limitations of EDs serving as board members include conflicts of interest when the board sets the ED’s salary, complicated reporting relationships, and blurred lines between governing bodies and staff. On the other hand, an ED that is part of a governing board can provide context about day-to-day operations and ultimately lead to better informed decisions, while also giving the ED more credibility and authority.

We also consider information about leadership’s commitment to transparency by looking at available information on the charity's website, such as key staff members, financial information, and board meeting notes. We require organizations selected for evaluation to be transparent with ACE throughout the process. Although we value transparency, we do not expect all organizations to be transparent with the public about sensitive information. For example, we recognize that organizations and individuals working in some regions or on some interventions could be harmed by making information about their work public. In these cases, we favor confidentiality over transparency.

In addition, we utilize our culture survey to ask staff to identify the extent to which they feel that leadership is competently guiding the organization.

Finally, there are specific considerations for charities that work internationally. For instance, “North–South" power imbalances—differences between more and less developed countries’ autonomy and decision-making abilities—can occur within the same organization or between organizations working in partnership. We think that it is important that charities, especially those from developed countries, prevent and address power imbalances by, for instance, creating opportunities for the national affiliates to influence decision-making at the international level, including “Southern" majorities in boards of governance.23 We ask leadership to elaborate on their approach and report measures they take.

Organizational policies

We ask organizations undergoing evaluation to provide a list of their human resources policies, and we elicit the views of staff and volunteers through our culture survey. Administering ACE's culture survey to all staff members, as well as volunteers working at least 20 hours per month, is an eligibility requirement to be recommended as an ACE Top or Standout Charity. However, ACE does not require individual staff members or volunteers at participating charities to complete the survey. We recognize that surveying staff and volunteers could (i) lead to inaccuracies due to selection bias, and (ii) may not reflect employees’ true opinions as they are aware that their responses could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer. In our experience, it is easier to uncover issues with an organization’s culture than it is to assess how strong an organization’s culture is. Therefore, we focus on determining whether there are issues in the organization’s culture that have a negative impact on staff productivity and well-being.

We assume that employees in the nonprofit sector have incentives that are material, purposive, and solidary.24 Since nonprofit sector wages are typically below for-profit wages, our survey elicits wage satisfaction from all staff. Additionally, we request the organization’s benefit policies regarding time off, health care, and training and professional development. As policies vary across countries and cultures, we do not evaluate charities based on their set of policies and do not expect effective charities to have all policies in place.

To capture whether the organization also provides non-material incentives, e.g., goal-related intangible rewards, we elicit employee engagement using the Gallup Q12 survey. We consider an average engagement score below the median value (i.e., below four) of the scale a potential concern.

ACE believes that the animal advocacy movement should be safe and inclusive for everyone. Therefore, we also collect information about policies and activities regarding representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI). We use the terms “representation" and “diversity" broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of certain social identity characteristics (called “protected classes" in some countries).25 Additionally, we believe that effective charities must have human resources policies against harassment26 and discrimination,27 and that cases of harrassment and discrimination in the workplace should be addressed appropriately. If a specific case of harassment or discrimination from the last 12 months is reported to ACE by several current or former staff members or volunteers at a charity, and said case remains unaddressed, the charity in question is ineligible to receive a recommendation from ACE.

Information and Analysis

Leadership staff

In this section, we list each charity’s President (or equivalent) and/or Executive Director (or equivalent), and we describe the board of directors. This is completed for the purpose of transparency and to identify the relationship between the ED and board of directors.

- Founder and Chief Executive Officer (CEO): Bruce Friedrich, involved in the organization for six years

- Number of members on board of directors: five members, including CEO Bruce Friedrich

GFI is currently hiring a President, which is a new role for the organization.

About 96% of staff respondents to our culture survey at least somewhat agreed that GFI’s leadership team guides the organization competently, while about 4% at least somewhat disagreed.

GFI has been transparent with ACE during the evaluation process. In addition, GFI’s audited financial documents are available on the charity’s website or GuideStar. Lists of board members and key staff members are available on the charity’s website.

GFI has expanded from the U.S. to Israel, Brazil, India, Europe (Belgium), and Asia Pacific (Singapore). GFI reports that while their non-U.S. affiliates work closely with GFI U.S. and are largely funded by them, they are independent organizations that make their own plans and set their own agendas. We are uncertain whether GFI’s top leadership is aware of any potential power imbalances between developed and developing country parties.

Culture

In the U.S. GFI has 59 staff members (including full-time, part-time, and contractors) and 12 volunteers. 49 staff members and no volunteers responded to our survey, yielding response rates of 83% and 0%, respectively.

GFI has a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. Of the staff that responded to our survey, about 22% report that they are at least somewhat dissatisfied with their wage. GFI offers 12–18 days of paid time off per year, 10 sick days, five days of personal leave, and healthcare coverage. GFI also offers all staff members a two-week sabbatical on their five year anniversary and has policies that support remote working. About 12% of staff members report that they are at least somewhat dissatisfied with the benefits provided. Additional policies are listed in the table below.

General compensation policies

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A formal compensation policy to determine staff salaries | |

| Paid time off

GFI offers vacation time to full-time employees at the following rates based on tenure:

Part-time employees (defined as employees who work at least 20 hours per week) accrue half this time at half the rate. GFI staff receive an additional two-week sabbatical on their five year anniversary. |

|

| Sick days and personal leave

All staff automatically receive 80 hours per year (10 days) and can roll over time up to 160 hours (four weeks). Sick time can be used in the case of personal illness (including mental), caring for immediate family members who are ill, medical appointments, and up to 16 hours annually for the care of companion animals. All staff also receive 5 days of personal leave each year. |

|

| Healthcare coverage

GFI offers medical coverage for employees, spouses/partners, and dependents. They also offer dental and vision coverage, and life and disability insurance. |

|

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| Annual (or more frequent) performance evaluations | |

| Formal onboarding or orientation process | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support | |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Remote work option | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) |

The average score in our engagement survey is 6.4 (on a 1–7 scale), suggesting that on average, staff do not exhibit a low engagement score. GFI has staff policies against harassment and discrimination. None of the staff report that they themselves have experienced harassment or discrimination at their workplace during the last twelve months, while a few report to have witnessed harassment or discrimination of others. None of the respondents agree that the situation was handled appropriately. See all other related policies in the table below.

We feel it’s important to note that several of GFI’s current and former employees have reached out to us to provide input on our evaluation of GFI. According to those who contacted ACE and responded to the culture survey, there appears to be several employees (current and former) reporting both retaliation and a fear of retaliation from top leadership for voicing disagreements at the organization. Because ACE prioritizes the confidentiality of those reports, we did not share details of the reports with GFI’s leadership, and therefore they have not conducted a full investigation to verify the reports.

Policies related to representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI)

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics/conduct | |

| A written statement that the organization does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels, up to and including the board of directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| Documentation of all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

Our Assessment

We have some concerns about reports of alleged retaliation by GFI’s top leadership towards current and former staff. We think GFI could benefit from having an independent board. We do, however, positively note that i) GFI is transparent toward external stakeholders, ii) staff agree that leadership guides the organization competently, iiii) the charity has a written statement that they do not tolerate discrimination and harassment, and iv) staff are generally engaged and satisfied with their job.

GFI has provided a detailed response to our assessment of their leadership and culture.

On average, our team considers advocating for welfare improvements to be a positive and promising approach. However, there are different viewpoints within ACE’s research team on the effect of advocating for animal welfare standards on the spread of anti-speciesist values. There are concerns that arguing for welfare improvements may lead to complacency related to animal welfare and give the public an inconsistent message—e.g., see Wrenn (2012). In addition, there are concerns with the alliance between nonprofit organizations and the companies that are directly responsible for animal exploitation, as explored in Baur and Schmitz (2012).

The weightings used for calculating these country scores are scale (25%), tractability (55%), and regional influence (20%).

For arguments supporting the view that the most important consideration of our present actions should be their impact in the long term, see Greaves & MacAskill (2019) and Beckstead (2019).

This estimate is based on a 9% reduction in animal-based meals consumed at the University of California – Los Angeles’ cafeteria, following the introduction of Impossible Foods’ plant-based ground beef options to half of the cafeteria. We believe that introducing plant-based options to both halves of the cafeteria would likely have doubled this amount. See Malan (2020).

Stated preferences of meat eaters between conventional and plant-based meat in Vietnam from Globescan (2020).

To be selected for evaluation, we require that a charity has a revenue of at least about $50,000 and faces no country-specific regulatory barriers to receiving money from ACE.

Note that GFI did not provide projections for their expenditures in 2023 and did not provide projections for their assets in 2022 and 2023.

GFI reports that they build their budget each year based on the gifts received by December 31st of the preceding year. Because GFI’s expenses will increase in 2022, their 2021 fundraising goal must also increase, which means that GFI will need to fundraise considerably more than their 2021 expense budget in order to meet the 2022 budget demands.

Operations are shared between GFI Asia Pacific and GFI India.

As GFI did not provide projected expenditures for 2023, we were unable to estimate the change in expenditure for their other expansion plans over 2023.

A negative amount for change in expenditure here means that the reported difference in program costs between 2022 and 2021 is larger than the total change in expenditure. For details, see the RFMF sheet.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness.

Clark and Wilson (1961), as cited in Rollag (n.d.)

Examples of such social identity characteristics are: race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, and genetic information.

Harassment can be non-sexual or sexual in nature: ACE defines non-sexual harassment as unwelcome conduct—including physical, verbal, and nonverbal behavior—that upsets, demeans, humiliates, intimidates, or threatens an individual or group. Harassment may occur in one incident or many. ACE defines sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances; requests for sexual favors; and other physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors of a sexual nature when (i) submission to such conduct is made explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual's employment; (ii) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting the targeted individual; or (iii) such conduct has the purpose or effect of interfering with an individual's work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

ACE defines discrimination as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of or hostility toward an individual on the basis of certain characteristics (called “protected classes" in some countries), such as race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, or genetic information.