The Humane League

Archived Review| Review Published: | 2021 |

| Current Version | 2023 |

Archived Version: 2021

What does THL do?

The Humane League (THL) was founded in 2005. THL currently operates in the U.S., Mexico, the U.K., and Japan, where they work to improve animal welfare standards through grassroots campaigns, movement building, veg*n advocacy, research, and advocacy training, as well as through corporate, media, and community outreach. They work to build the animal advocacy movement internationally through the Open Wing Alliance (OWA), a coalition founded by THL whose mission is to end the use of battery cages globally. THL also works to decrease the consumption of animal products through seasonal promotion of the Veganuary veg*n pledge program.

What are their strengths?

We believe that THL’s corporate campaigns to raise the welfare standards of chickens and monitor companies’ compliance, as well as their movement-building work through the OWA, are highly impactful. THL’s track record demonstrates significant success, especially in improving the welfare standards of farmed animals and strengthening the animal advocacy movement. THL seems to have played an important role in promoting corporate campaigns outside of the U.S. by training and collaborating with other groups through the OWA.

What are their weaknesses?

We have concerns about some reports of alleged discrimination or harrassment that a few staff members believe were not handled appropriately. However, leadership have taken actions to handle the complaints and have hired independent investigators.

Why did THL receive our top recommendation?

We believe that THL’s corporate campaigns and work to strengthen the animal advocacy movement are especially strong. THL often takes the lead in collaborating with other groups to facilitate knowledge-sharing about their strategic approach. They seem to have played an important role in strengthening the animal advocacy movement outside of the U.S. by training and collaborating with other organizations through the OWA.

We find THL to be an excellent giving opportunity because of their strong programs aimed at improving the welfare standards of farmed animals and strengthening the animal advocacy movement across multiple countries.

How much money could they use?

We believe that overall, THL continues to have room for $4,881,000 of additional funding in 2022 and $5,249,000 in 2023. We expect that they would use additional funds to start a new program on public policy work and expand their animal welfare campaigns, movement building, and research programs.

The Humane League has been one of ACE’s Top Charities since August 2012, through a volunteer process that did not include published reviews. In 2014, THL was awarded Top Charity status in our first official round of ACE charity evaluations and has been renewed as a Top Charity ever since.

Programs

A charity that performs well on this criterion has programs that we expect are highly effective in reducing the suffering of animals. The key aspects that ACE considers when examining a charity’s programs are reviewed in detail below.

Method

In this criterion, we assess the effectiveness of each of the charity’s programs by analyzing (i) the interventions each program uses, (ii) the outcomes those interventions work toward, (iii) the countries in which the program takes place, and (iv) the groups of animals the program affects. We use information supplied by the charity to provide a more detailed analysis of each of these four factors. Our assessment of each intervention is informed by our research briefs and other relevant research.

At the beginning of our evaluation process, we select charities that we believe have the most effective programs. This year, we considered a comprehensive list of animal advocacy charities that focus on improving the lives of farmed or wild animals. We selected farmed animal charities based on the outcomes they work toward, the regions they work in, and the specific animal group(s) their programs target. We don’t currently consider animal group(s) targeted as part of our evaluation for wild animal charities, as the number of charities working on the welfare of wild animals is very small.

Outcomes

We categorize the work of animal advocacy charities by their outcomes, broadly distinguishing whether interventions focus on individual or institutional change. Individual-focused interventions often involve decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Institutional change involves improving animal welfare standards, increasing the availability of animal-free products, or strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

We believe that changing individual habits and beliefs is difficult to achieve through individual outreach. Currently, we find the arguments for an institution-focused approach1 more compelling than individual-focused approaches. We believe that raising welfare standards increases animal welfare for a large number of animals in the short term2 and may contribute to transforming markets in the long run.3 Increasing the availability of animal-free foods, e.g., by bringing new, affordable products to the market or providing more plant-based menu options, can provide a convenient opportunity for people to choose more plant-based options. Moreover, we believe that efforts to strengthen the animal advocacy movement, e.g., by improving organizational effectiveness and building alliances, can support all other outcomes and may be relatively neglected.

Therefore, when considering charities to evaluate, we prioritize those that work to improve welfare standards, increase the availability of animal-free products, or strengthen the animal advocacy movement. We give lower priority to charities that focus on decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals. Charities selected for evaluation are sent a request for more in-depth information about their programs and the specific interventions they use. We then present and assess each of the charities’ programs. In line with our commitment to following empirical evidence and logical reasoning, we use existing research to inform our assessments and explain our thinking about the effectiveness of different interventions.

Countries

A charity’s countries and regions of operations can affect their work with regard to scale, neglectedness, and tractability. We prioritize charities in countries with relatively large animal agricultural industries, few other charities engaged in similar work, and in which animal advocacy is likely to be feasible and have a lasting impact. In our charity selection process, we used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI), which combines proxies for scale, tractability, and global influence to create country scores.4 To assess neglectedness, we used our own data on the number of organizations that we are aware of working in each country. Below we present these measures for the countries that THL operates in.

Animal groups

We prioritize programs targeting specific groups of animals that are affected in large numbers5 and receive relatively little attention in animal advocacy. Of the 187 billion farmed vertebrate animals killed annually for food globally, 110 billion are farmed fishes and 66.6 billion are farmed chickens, making these impactful groups to focus on. There are at least 100 times as many wild vertebrates as there are farmed vertebrates.6 Given the large number of wild animals and the small number of organizations working on their welfare, we believe wild animal advocacy also has potential for high impact despite its lower tractability.

A note about long-term impact

Each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.7 The potential number of animals affected increases over time due to population growth and an accumulation of generations. Thus, we would expect that the long-term impacts of an action would likely affect more animals than the short-term impacts of the same action. Nevertheless, we are highly uncertain about the particular long-term effects of each intervention. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew toward overemphasizing short-term effects.

Information and Analysis

Cause areas

THL’s programs focus exclusively on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we think is a high-priority cause area.

Countries

THL develops their programs in the U.S., Mexico, the U.K., and Japan. Their headquarters are in the U.S.

We used Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI) with the suggested weightings of scale (25%), tractability (55%), and influence (20%) to determine each country’s total FAOI score. We report this score along with the country’s global ranking from a total of 60 countries in the following format: FAOI score(global ranking). The U.S., Japan, the U.K., and Mexico have the following scores and rankings, respectively: 53.92(2), 29.92(6), 27.90(7), and 22.26(13). According to the comprehensive list of charities we are aware of, there are about 724 farmed animal advocacy organizations, excluding sanctuaries. From this list, we found 220 in the U.S., 61 in the U.K., nine in Mexico, and four in Japan. All of these countries are relatively high priority based on their FAOI rankings, and we believe that farmed animal advocacy in Mexico and Japan is especially neglected. Overall, we believe that THL works in high-priority countries.

THL created the Open Wing Alliance (OWA), which is a global coalition of currently 77 animal advocacy organizations from 63 different countries working to end cages for egg-laying hens. Although THL does not work directly in all of these countries, we believe THL has indirectly influenced work in many countries through the OWA.

Description of programs

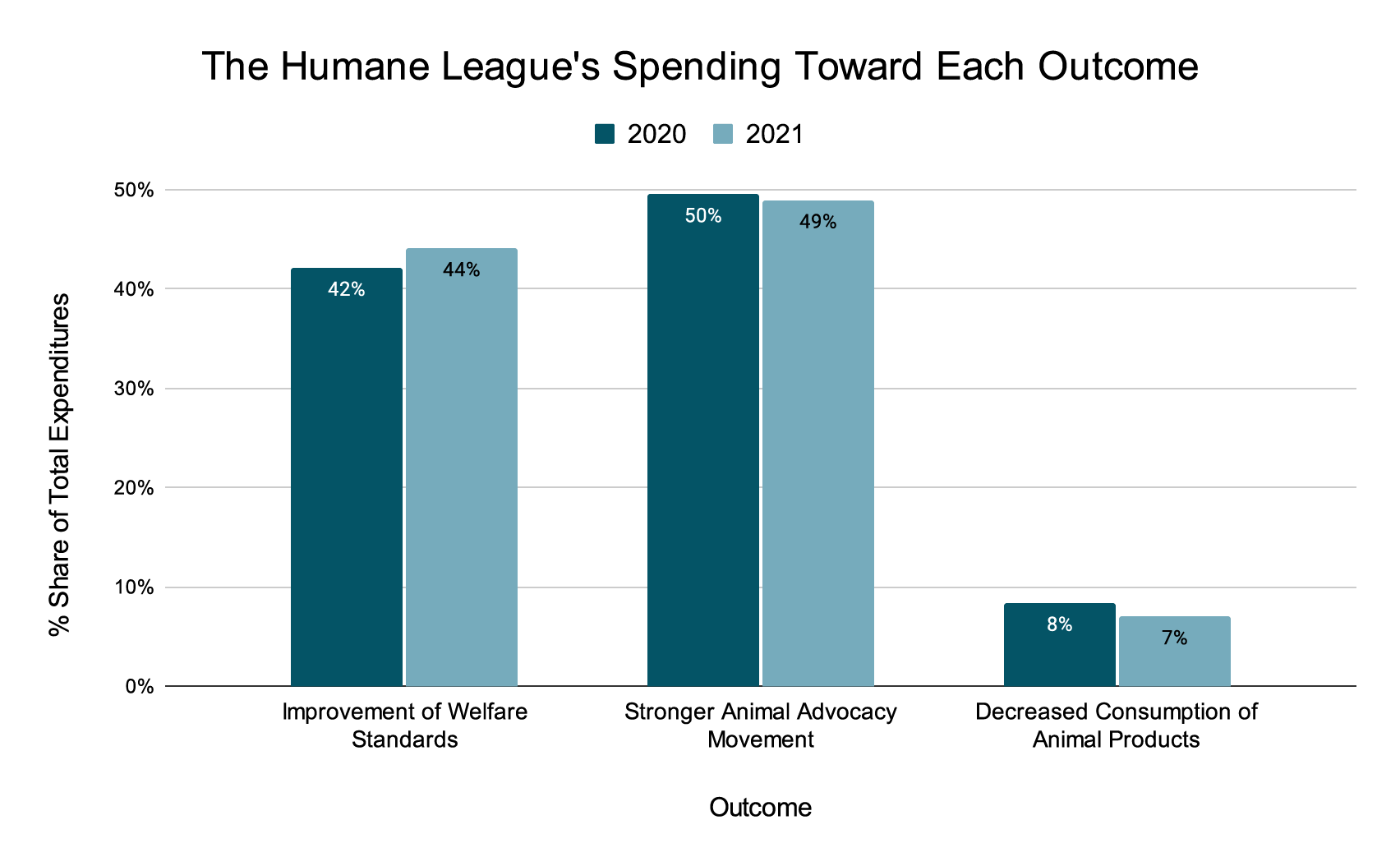

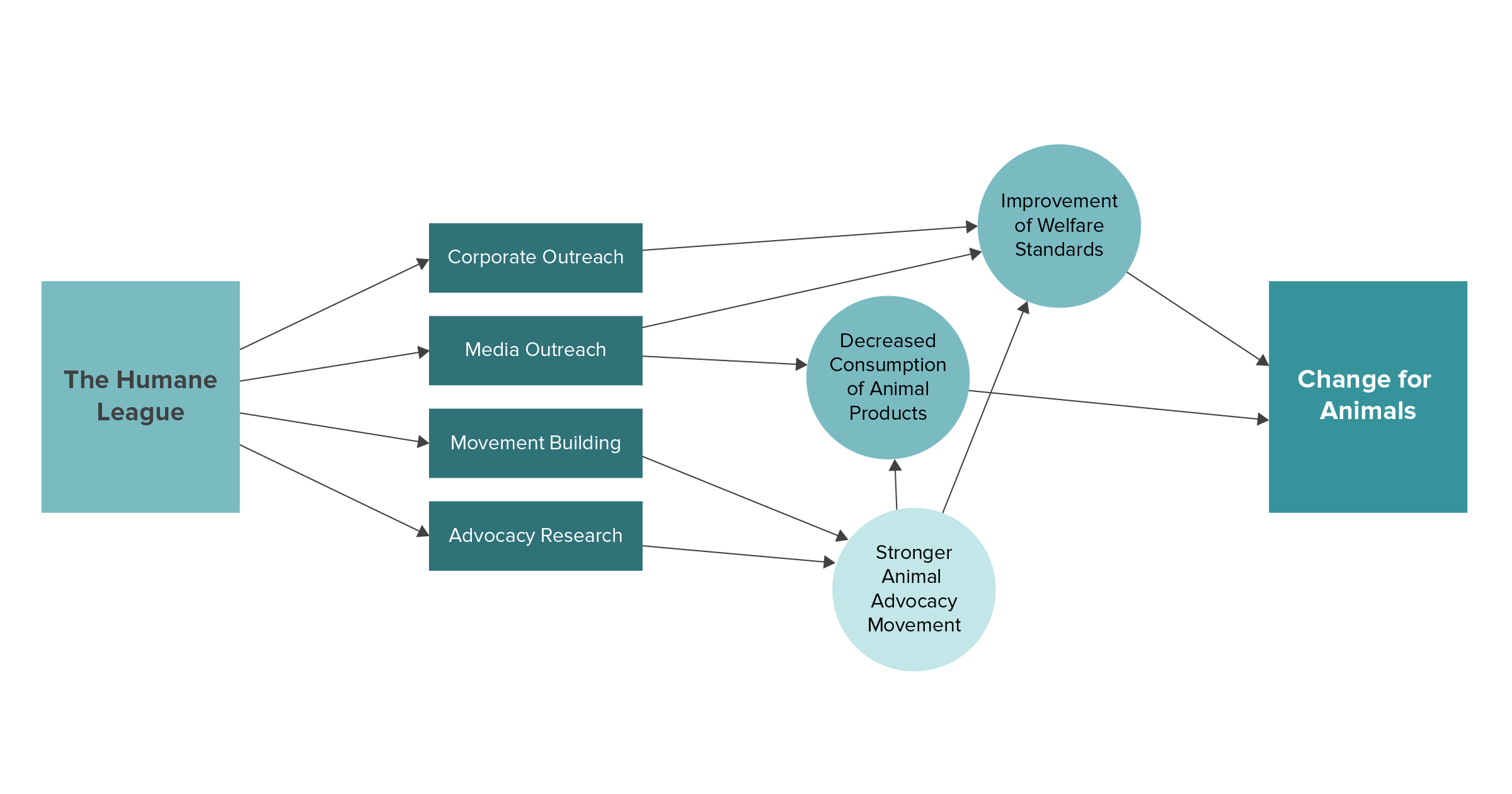

THL pursues different avenues for creating change for animals. Their work focuses on improving welfare standards and strengthening the animal advocacy movement, and to a lesser extent, also aims to decrease the consumption of animal products.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

Below, we describe each of THL’s programs, listed in order of the financial resources devoted to them in 2020 (from highest to lowest). We list major accomplishments for each program, if a track record is available.

THL’s programs

This program focuses on creating institutional and legislative changes that impact farmed animals (such as commitments to higher-welfare breeds for broiler chickens8; cage-free commitments for egg-laying hens; and other improvements for pigs, cows, and fishes) in the U.S., the U.K., Mexico, Japan, and 59 additional countries through the Open Wing Alliance.

Main interventions

- Corporate outreach

- Grassroots support of legislation/ballots

Key historical accomplishments

- Achieved, along with other organizations, hundreds of cage-free and broiler chicken corporate commitments (for the list of commitments, see the THL-designed and coalition-shared website Chicken Watch).

- Participated in a coalition that supported the passage of Prop 12 in California (2018)

- Achieved a commitment from the United Egg Producers (UEP) to eliminate the culling of male chicks (2016)

This program focuses on building the movement through providing grants as well as recruiting, training, and engaging volunteers and coalition partners. In particular, this program aims to increase the number of people in THL’s network and increase collaboration with other organizations targeting farmed animals in the U.S., the U.K., Mexico, Japan, and 59 additional countries through the Open Wing Alliance.

Main interventions

- Volunteer and student recruitment and training

- OWA member recruitment, training, and grants

- Fellowship program

Key historical accomplishments

- Had active volunteers (“Changemakers”) in 396 communities in 43 states in the U.S. (as of mid-2021), 155 active students in the Student Alliance for Animals in the U.S. (as of mid-2021), and about 12,000 Fast Action Network members (as of 2020)

- Launched an online volunteer initiative in Mexico and enrolled 115 volunteers in training (2020)

- Organized events, launched the Activist Bootcamp webinar series, and hosted the Aquatic Animal Welfare Conference 2020

- Launched the Changemaker Training Center for volunteers in the U.S. (2019)

- Has recruited 78 member organizations, run 17 summits, organized 35 training events and webinars, and awarded about $3.7 million in grants to member organizations since founding the OWA in 2016 (as of mid-2021)

This program focuses on educating individuals about factory farming and inspiring them to reduce consumption of animal products. It is primarily implemented in the U.S. and the U.K., but THL also provides materials in Spanish.

Main interventions

- Veg*n outreach leaflets, newsracks, and cookbooks

- Online ads

- Media outreach

- Social media outreach

Key historical accomplishments

- Had about 4.3 million Veg Starter Guide downloads in English, Spanish, Ukrainian, and Hindi since 2018

- Launched a webpage with dietary advice, published plant-based cookbooks, and ran a plant-based revolution campaign (2018–2020)

- Had 1.25 million followers on social media

- Ran online ads that inspired about 18 million landing page visits (2019)

This program focuses on conducting independent advocacy research via The Humane League Labs and other projects. THL Labs aims to transparently design, execute, and publish interdisciplinary research on farmed animal advocacy using a wide range of research methods, including cross-sectional surveys, experiments, and observational studies.

Main interventions

- Advocacy research

Key historical accomplishments

- Published at least 18 research reports on the impact of informational animal advocacy materials, the role of barriers in reducing animal product consumption, and potential improvements to animal advocacy research quality (2013–2021)

Research for intervention effectiveness

Corporate outreach

There is some evidence that corporate outreach leads food companies to change their practices related to hen welfare. Šimčikas9 found that the follow-through rate of cage-free corporate commitments ranges from 48–84%. Cost-effectiveness estimates vary widely, and it is unclear which is the most accurate. Šimčikas estimates that corporate campaigns affect nine to 120 hen-years (i.e., years of chicken life) per dollar spent.

THL’s main historical achievements are focused on securing cage-free commitments for egg-laying hens and welfare commitments for broiler chickens. Cage-free housing systems are believed to reduce suffering by increasing the space available to egg-laying hens and providing them opportunities to perform important behaviors, although mortality may increase during the transition process, and there is some risk that it may remain elevated.10 THL reported that they have a 60% implementation rate of their corporate commitments and have impacted 10 hen-years per dollar received.11

THL also campaigns for companies to switch to higher-welfare (but likely slower-growing) breeds of broiler chickens and to commit12 to provisions on stocking density, lighting, and environmental enrichments. Such commitments may lead to higher welfare but also to more animal days lived in factory farms.13

Movement building

There is currently no empirical evidence that reviews the effectiveness of movement building in animal advocacy. However, we believe that capacity-building projects have the potential to help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Furthermore, building alliances with key influencers, institutions, or social movements could expand the audience and impact of animal advocacy organizations and projects, leading to net positive outcomes for animals. Additionally, ACE’s 2018 research and Harris14 suggest that capacity building and building alliances are currently neglected relative to other interventions aimed at influencing public opinion and industry.

Veg outreach

According to a recent two-year study,15 distributing animal advocacy pamphlets to individuals was associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in animal product consumption for a small subset of the sample: those who identified as vegetarian, those who thought more about animal welfare, and those who said they were willing to change their diet. However, this effect on diet only lasted for two months—the leafleting intervention did not have any statistically significant effects over the course of the entire study. Between this study and ACE’s 2017 meta-analysis about leafleting, we are uncertain about the effectiveness of individual outreach methods, such as distributing information pamphlets.

Supporting or conducting animal advocacy research

We believe that conducting advocacy research is a generally promising intervention, especially when considering its potential effects in the longer term (defined as more than one year). We believe that THL Labs’ reports have the potential to (i) influence priorities, (ii) inform the implementation of interventions, and (iii) build the field of animal advocacy research. Due to the lack of research on the extent that animal advocacy research results are used by the movement to prioritize and implement their work, our confidence in the short-term effects of this intervention is low. Also, we acknowledge that we may be generally biased to favor this intervention because part of our work consists of conducting and supporting relevant research—see our assessment of the effects of producing advocacy research.

Our Assessment

We think that THL’s Animal Welfare Campaigns and Movement Building Programs, aimed at improving welfare standards and strengthening the animal advocacy movement, are particularly effective. There is some evidence supporting this claim, as studies suggest that corporate outreach to secure chicken welfare commitments can impact a large number of animals. Despite the lack of evidence for the effectiveness of movement-building interventions in general, we think that THL has strongly contributed to strengthening the animal advocacy movement by founding and running the OWA. Through the OWA, THL has provided funding and advice to multiple animal advocacy organizations around the world.

We consider THL’s work in the U.S. and Japan to be particularly effective based on the high number of animals and the high tractability of farmed animal advocacy work in these countries.

Overall, we think that almost all of THL’s spending on programs goes toward outcomes and helping species that we think are a high priority.

Room for More Funding

A new recommendation from ACE could lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding. In this criterion, we investigate whether a charity is able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in or, if the charity has a prior recommendation status, whether they will continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation.

Method

In the following section, we inspect the charity’s plans for expansion as well as their financials, including revenue and expenditure projections.

The charities we evaluate typically receive revenue from a variety of different sources, such as individual donations or grants from foundations.16 In order to guarantee that a charity will raise the funds needed for their operations, they should be able to predict changes in future revenue. To estimate charities’ room for more funding, we request records of their revenue since 2019 and ask what they predict their revenue will be in 2021–2023. A review of the literature on nonprofit finance suggests that revenue diversity may be positively associated with revenue predictability if the sources of income are largely uncorrelated.17 However, a few sources of large donations—if stable and reliable—may also be associated with high performance and growth. Therefore, in this criterion, we also indicate the charities’ major sources of income.

We present the charities’ reported plans for expansion of each program as well as other planned changes for the next two years. We do not make active suggestions for additional plans. However, we ask charities to indicate how they would spend additional funding that we expect would come in as a result of a new recommendation from ACE, considering that a Standout Charity status and a Top Charity status would likely lead to a $100,000 or $1,000,000 increase in funding, respectively. Note that we list the expenditures for planned non-program expenses but do not make any assessment of the charity’s overhead costs in this criterion, given that there is no evidence that the total share of overhead costs is negatively related to overall effectiveness.18 However, we do consider relative overhead costs per program in our Cost-Effectiveness criterion. Here we focus on evaluating whether additional resources are likely to be used for effective programs or other beneficial changes in the organization. The latter may include investments into infrastructure and efforts to retain staff, both of which we think are important for sustainable growth.

It is common practice for charities to hold more funds than needed for their current expenses (i.e., reserves) in order to be able to withstand changes in the business cycle or other external shocks that may affect their incoming revenue. Such additional funds can also serve as investments into future projects in the long run. Thus, it can be effective to provide a charity with additional funds to secure the stability of the organization or provide funding for larger, future projects. We do not prescribe a certain share of reserves, but we suggest that charities hold reserves equal to at least one year of expenditures, and we increase a charity’s room for more funding if their reserves in 2021 are less than 100% of their total expenditure.

Finally, we aggregate the financial information and the charity’s plans to form an assessment of their room for more funding. All descriptive data and estimations can be found in this sheet. Our assessment of a charity’s ability to effectively absorb additional funding helps inform our recommendation decision.

Information and Analysis

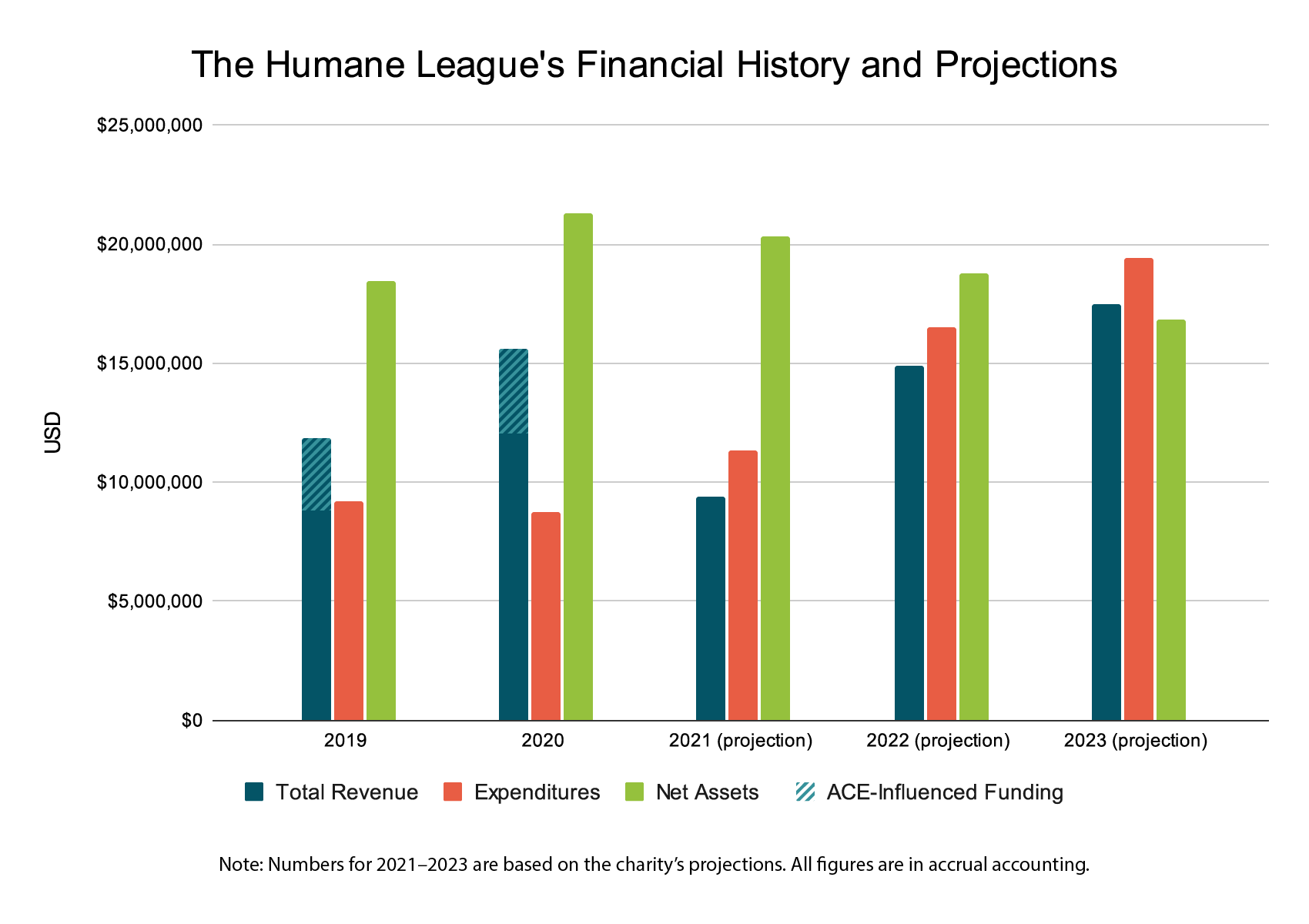

The chart below shows THL’s revenues, expenditures, and net assets from 2019–2020, as well as projections for the years 2021–2023. The information is based on the charity’s past financial data and their own predictions for the years 2021–2023.

THL receives the majority of their income from donations, 0.05% from their own work, and 6.95% from capital investments.19 In 2018, they received a grant of $10,000,000 that was disbursed through 2021. In 2020, they received 46% of their funding from donations larger than 20% of their annual revenue, and also received several large donations that will be disbursed over multiple years, leading to a spike in revenue. These donations include, among others, a grant of $3,600,000 that will be disbursed over two years and restricted to the OWA.

THL has also received funding influenced by ACE as a result of their recommended charity status, which they have held for the past nine years. As such, their room for more funding analysis will focus on our assessment of whether they will continue to effectively absorb funding that comes from our recommendation.

According to THL’s reported projections, their estimated revenue in 2022 and 2023 will not cover their expenditures. Subtracting their projected annual revenue from their projected annual expenditures, we find a funding gap of about $1,564,000 in 2022 and $1,932,000 in 2023.20 We estimate that THL received $3,064,000 in 2019 and $3,571,000 in 2020 as a result of their recommended charity status; should THL lose their recommended charity status, their projected revenue may be lowered, resulting in more room for funding.

With more than 100% of their current annual expenditures held in net assets—as projected by THL for 2021—we believe that they hold a sufficient amount of reserves.

Below, we list THL’s plans for expansion for each of their programs as well as other planned expenditures, such as administrative costs, wages, and training. We do not verify the feasibility of the plans or the specifics of how changes in expenditure will cover planned expansions. Reported changes in expenditure are based on THL’s own estimates of changes in program expenditures for 2021–2022 and 2022–2023.

THL plans to start a new program on public policy work and expand their animal welfare campaigns, movement building, and research programs. More details can be found in the corresponding estimation sheet and the supplementary materials. Readers may also consult THL’s plans for 2021.

- Hire three Open Wing Alliance team members in 2022

- Hire three to five team members supporting U.S. campaigns in 2022

- Hire four to six team members in the U.K. in 2022

- Hire three to five team members in Mexico in 2022

- Continue expansion in 2023

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $1,160,000

- 2023: $698,000

- Hire a National Director of Organizing

- Hire additional Communications and Marketing team members in the U.S.

- Hire additional Regional Coordinators, including in Africa and the Middle East, for OWA

- Hire a Volunteer Coordinator in the U.K.

- Hire a team member to work on a program with universities in Mexico

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $1,088,000

- 2023: $729,000

- No changes

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $72,000

- 2023: $56,000

- Hire Animal Welfare Specialists to focus on THL’s programs

Reported change in expenditure

- 2022: $71,000

- 2023: $55,000

- Hire a Director of Public Policy and a small team to focus on public policy work at the local and state level as part of a new program

Estimate of expenditure

- 2022: $2,749,000

- 2023: $1,418,000

Our Assessment

THL plans to focus future expansions on their animal welfare campaigns, movement building, and research. For donors influenced by ACE wishing to donate to THL, we estimate that the organization can continue to effectively absorb funding that we expect to come with a recommendation status.

Based on (i) THL’s own projections that their projected revenue will not cover their expenditures, (ii) our assessment that they have sufficient reserves, and (iii) our assumption that a loss of recommendation status would result in a decrease in funding, we believe that overall, THL continues to have room for $4,881,000 of additional funding in 2022 and $5,249,000 in 2023. See our Programs criterion for our assessment of the effectiveness of their programs.

It is possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or that they could come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. If a charity receives a recommendation as Top Charity, we check in mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented above to indicate whether we still expect them to be able to effectively absorb additional funding at that time.

Cost Effectiveness

Method

A charity’s recent cost effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component in understanding how cost effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources over the past 18 months and compare that to the outputs they have achieved in each of their main programs during that time. We seek to understand whether each charity has been successful at implementing their programs in the recent past and whether past successes were achieved at a reasonable cost. We only complete an assessment of cost effectiveness for programs that started in 2019 or earlier and that have expenditures totaling at least 10% of the organization’s annual budget.

Below, we report what we believe to be the key outputs of each program, as well as the total program expenditures. To estimate total program expenditures, we take the reported expenditures for each program and add a portion of their non-program expenditures weighted by the size of the program. This allows us to incorporate general organizational running costs into our consideration of cost effectiveness.

We spend a significant portion of our time during the evaluation process verifying the outputs charities report to us. We do this by (i) searching for independent sources that can help us verify claims, and (ii) directing follow-up questions to charities to gather more information. We adjusted some of the reported claims based on our verification work.

Information and Analysis

Overview of expenditures

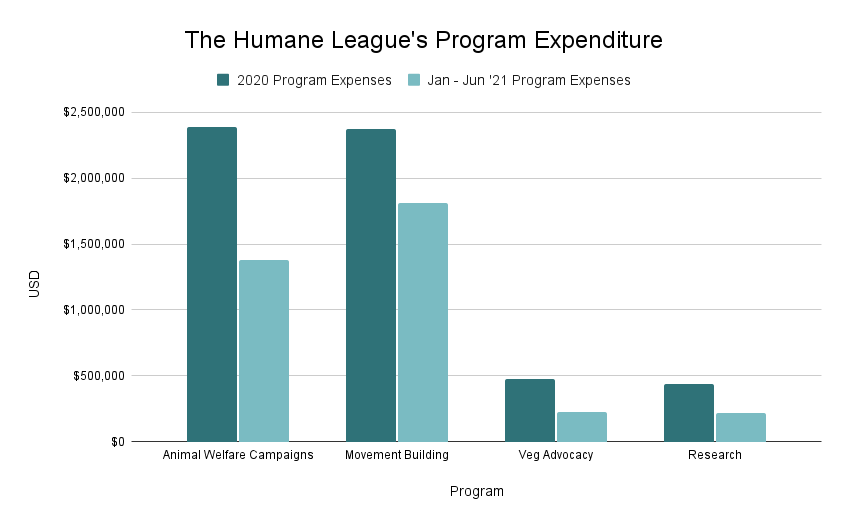

The following chart shows THL’s total program expenditures from January 2020 – June 2021.

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Secured at least 60 welfare commitments for chickens raised for meat in the U.S., U.K., Europe, and globally (alone and in cooperation with other groups)

- Secured at least 13 cage-free egg commitments globally (alone and in cooperation with other groups)

- Followed up with companies who had previously made cage-free commitments, with 85% on track to fulfill their commitments

- Secured 286 national and regional cage-free policies and 169 broiler chicken welfare policies through the OWA, including the very first commitments in Kenya, Indonesia, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Pakistan

- Initiated work on fish welfare in the U.K. by introducing fish slaughter as an issue for attention with relevant ministries, building collaborations with other advocacy organizations, and producing a report21 on effective strategies for communicating farmed fish advocacy to the public

Expenditures22 (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $5,730,000

THL’s animal welfare campaigns focus on securing commitments to improve welfare standards for farmed animals. This work generally seeks to make incremental improvements to the conditions in which animals live, e.g., in factory farms. For farmed animals, welfare reforms generally only result in small improvements to their living conditions. However, this is balanced by the large numbers of animals who can be impacted, and there is some evidence to suggest that farmed animal welfare reforms are likely to be very cost effective in the short term.23 In general, we expect a focus on chickens and fishes to be the most cost effective, as they are among the most numerous groups of farmed animals.

THL actively follows up on whether companies follow through on their welfare commitment deadlines. There is some evidence that corporate outreach leads food companies to change their practices related to hen welfare. Šimčikas24 found that the follow-through rate of cage-free corporate commitments ranges from 48–84% and that corporate campaigns affect nine to 120 hen-years per dollar spent. Cost-effectiveness estimates vary widely, and it is unclear which is the most accurate.

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Distributed $2,075,000 in OWA grants to 40 organizations around the world with the goal of developing corporate campaigns to advance chicken welfare

- Recruited nine new member groups to the OWA

- Organized six summits focused on training OWA members in corporate outreach, campaigning, and strategic planning for cage-free commitments

- Hosted a virtual five-day Aquatic Welfare Conference

- Provided virtual training on corporate outreach to five organizations in Africa

- Successfully encouraged Franco Manca—a U.K. pizza chain with around 55 locations—to commit to the Better Chicken Commitment25

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $6,370,000

THL’s movement building program focuses on recruiting and training volunteers, and supporting other organizations through the OWA. In the past 18 months, THL has recruited nine new member groups to the OWA and provided training and $2,075,000 in grants to OWA groups. This strategy of sharing knowledge and distributing grants allows THL’s successful corporate campaigning model to spread internationally without the need for their own expansion, and it seems to be particularly cost effective.

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Resulted in 1.3 million downloads of veg literature

- Resulted in the viewing of 17 million minutes of factory farming and veg advocacy footage

- Reached 30,372,996 people through social media channels

- Engaged volunteers in a UK-wide project to mark eateries offering vegan options, resulting in a map

- Trained volunteers to advocate for vegan options at local eateries

- Partnered with Veganuary to drive thousands of potential supporters to a co-branded signup page, supporting them in 31 days of a plant-based diet

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $1,061,000

THL’s veg advocacy program focuses on encouraging individuals to reduce their consumption of animal products. They are primarily focused on using online ads to engage individuals who may be responsive to animal advocacy messaging and then provide them with animal advocacy literature. Given their size, they are likely benefiting from some economies of scale compared to smaller programs. After accounting for their budget, they do appear to have achieved a lot of reach with this program.

Key outputs, January 2020 – June 2021:

- Pre-registered for three studies on topics related to farmed animal welfare

- Published five research reports via The Humane League Labs regarding: milk consumption, an appeal to reduce animal product consumption, advocacy messaging, the Better Chicken Commitment, and a list of farmed animal advocacy research

- Published five reports via THL U.K. regarding: farmed fishes, the chicken industry, white striping disease, the European Chicken Commitment, and chicken welfare in the meal kit sector

- Published the OWA cage-free eggs fulfillment report

- Produced a Spanish-language survey on Mexican egg consumers’ attitudes toward animal welfare and corporate and governmental responsibility

Expenditures (USD), January 2020 – June 2021: $1,000,000

THL’s research program has individual outputs, so as a measure of cost effectiveness, we can estimate the average cost of each output—i.e., it costs them about $80,000 to publish each research report. That said, this is a somewhat simplistic quantification of cost effectiveness, as it doesn’t take into account other factors—e.g., the quality of the research, the likelihood that the research will be used, the potential impact the research would have if it were used, etc. Most of THL’s research is focused on farmed animals, especially chickens, which we believe to be a high-priority cause area.

Our Assessment

Given the outputs achieved using the stated expenditures per program, we do not have concerns about the cost effectiveness of THL’s animal welfare campaigns, movement building, and veg advocacy programs. The impacts of THL’s research program on animals are more indirect and may happen in the future; as such, the cost effectiveness is harder to assess using our methods. Given the outputs achieved using the stated expenditures for THL’s research program, we are less confident about the program’s cost effectiveness.

Leadership and Culture

A charity that performs well on this criterion has strong leadership and a healthy organizational culture. The way an organization is led affects its organizational culture, which in turn impacts the organization’s effectiveness and stability.26 The key aspects that ACE considers when examining leadership and culture are reviewed in detail below.

Method

We review aspects of organizational leadership and culture by capturing staff and volunteer perspectives via our culture survey, in addition to information provided by top leadership staff (as defined by each charity).

Assessing leadership

First, we consider key information about the composition of leadership staff and board of directors. There appears to be no consensus in the literature on the specifics of the relationship between board composition and organizational performance,27 therefore we refrain from making judgements on board composition. However, because donors may have preferences on whether the Executive Director (ED) or other top executive staff are board members or not, we note when this is the case. According to the Council on Foundations,28 risks of EDs serving as board members include conflicts of interest when the board sets the ED’s salary, complicated reporting relationships, and blurred lines between governing bodies and staff. On the other hand, an ED that is part of a governing board can provide context about day-to-day operations and ultimately lead to better-informed decisions, while also giving the ED more credibility and authority.

We also consider information about leadership’s commitment to transparency by looking at available information on the charity’s website, such as key staff members, financial information, and board meeting notes. We require organizations selected for evaluation to be transparent with ACE throughout the process. Although we value transparency, we do not expect all organizations to be transparent with the public about sensitive information. For example, we recognize that organizations and individuals working in some regions or on some interventions could be harmed by making information about their work public. In these cases, we favor confidentiality over transparency.

In addition, we utilize our culture survey to ask staff to identify the extent to which they feel that leadership is competently guiding the organization.

Finally, there are specific considerations for charities that work internationally. For instance, “North–South” power imbalances—differences between more and less developed countries’ autonomy and decision-making abilities—can occur within the same organization or between organizations working in partnership. We think that it is important that charities, especially those from developed countries, prevent and address power imbalances by, for instance, creating opportunities for the national affiliates to influence decision-making at the international level, including “Southern” majorities in boards of governance.29 We ask leadership to elaborate on their approach and report measures they take.

Organizational policies

We ask organizations undergoing evaluation to provide a list of their human resources policies, and we elicit the views of staff and volunteers through our culture survey. Administering ACE’s culture survey to all staff members, as well as volunteers working at least 20 hours per month, is an eligibility requirement to be recommended as an ACE Top or Standout Charity. However, ACE does not require individual staff members or volunteers at participating charities to complete the survey. We recognize that surveying staff and volunteers could (i) lead to inaccuracies due to selection bias, and (ii) may not reflect employees’ true opinions as they are aware that their responses could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer. In our experience, it is easier to uncover issues with an organization’s culture than it is to assess how strong an organization’s culture is. Therefore, we focus on determining whether there are issues in the organization’s culture that have a negative impact on staff productivity and well-being.

We assume that employees in the nonprofit sector have incentives that are material, purposive, and solidary.30 Since nonprofit sector wages are typically below for-profit wages, our survey elicits wage satisfaction from all staff. We also ask organizations to provide volunteer hours, because due to the absence of a contract and pay, volunteering may be a special case of uncertain work conditions. Additionally, we request the organization’s benefit policies regarding time off, health care, and training and professional development. As policies vary across countries and cultures, we do not evaluate charities based on their set of policies and do not expect effective charities to have all policies in place.

To capture whether the organization also provides non-material incentives, e.g., goal-related intangible rewards, we elicit employee engagement using the Gallup Q12 survey. We consider an average engagement score below the median value (i.e., below four) of the scale a potential concern.

ACE believes that the animal advocacy movement should be safe and inclusive for everyone. Therefore, we also collect information about policies and activities regarding representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI). We use the terms “representation” and “diversity” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of certain social identity characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries).31 Additionally, we believe that effective charities must have human resources policies against harassment32 and discrimination,33 and that cases of harrassment and discrimination in the workplace should be addressed appropriately. If a specific case of harassment or discrimination from the last 12 months is reported to ACE by several current or former staff members or volunteers at a charity, and said case remains unaddressed, the charity in question is ineligible to receive a recommendation from ACE.

Information and Analysis

Leadership staff

In this section, we list each charity’s President (or equivalent) and/or Executive Director (or equivalent), and we describe the board of directors. This is completed for the purpose of transparency and to identify the relationship between the ED and board of directors.

- President: David Coman-Hidy, involved in the organization for 11 years

- Executive Vice President: Andrea Gunn, involved in the organization for 8 years

- Number of members on board of directors: 6 members

THL did not have a transition in leadership in the last year.

About 92% of staff respondents to our culture survey at least somewhat agreed that THL’s leadership team guides the organization competently, while about 5% at least somewhat disagreed and 3% neither agreed nor disagreed.

THL has been transparent with ACE during the evaluation process. In addition, THL’s audited financial documents are available on the charity’s website or GuideStar. A list of board members and a list of key staff members is available on the charity’s website.

THL has expanded from the U.S. to Mexico, the U.K., and Japan. THL’s local teams are responsible for decision making for local programs carried out by the subsidiaries. In order to prevent and address potential power imbalances between developed and developing country parties, THL’s organizational structures enable local teams to set and carry out their own strategic plans. Each local team is led and staffed by people from those countries. THL U.K. is accountable to its own board.

Culture

THL has 109 staff (including full-time, part-time, and contractors). 92 staff responded to our survey, yielding a response rate of 84%. Of the 23 volunteers that responded to our survey, only 17% work at least 20 hours per month.

THL has a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. Of the staff that responded to our survey, about 15% report that they are at least somewhat dissatisfied with their wage. THL offers unlimited paid time off per year and full healthcare coverage. About 5% of staff report that they are at least somewhat dissatisfied with the benefits provided. Additional policies are listed in the table below.

General compensation policies

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A formal compensation policy to determine staff salaries | |

| Paid time off

Time off is essentially “unlimited” and may be used up to two consecutive weeks at a time. All staff are required to take a minimum of five consecutive days of paid time off (PTO) each year, and managers check with staff quarterly to ensure sufficient PTO is taken. Country-specific leave conforms to local regulations. |

|

| Sick days and personal leave

Employees may use PTO for any purpose including vacation, illness, bereavement, and personal appointments. Time off is essentially “unlimited” and may be used up to two consecutive weeks at a time. Country-specific leave conforms to local regulations. |

|

| Healthcare coverage

THL offers full coverage of employees’ healthcare premiums for the HSA Choice health plan and employer-paid life insurance and accidental death and dismemberment premiums. They also offer a 50% cost share of employees’ vision and dental premiums. Staff outside of the US have access to universal healthcare. THL provides supplemental benefits to enhance their insurance coverage. |

|

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| Annual (or more frequent) performance evaluations | |

| Formal onboarding or orientation process | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support | |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Remote work option | |

| Mandatory PTO minimum | |

| Pre-leave checklist for staff taking PTO to support “unplugged” vacation | |

| Private accommodations when traveling | |

| Twelve weeks of paid parental leave for any parent following the birth, adoption, or foster placement of a child (U.S.) | |

| Reimbursements provided for full-time staff: home internet, cell phone, and “bring your own device” | |

| Voluntary benefits offered to full-time staff: pet insurance benefits (veterinary and prescription costs), short-term disability, long-term disability, critical illness, accident and hospital indemnity, employer-paid employee assistance plan, 401k plan for all eligible staff to participate in | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) |

The average score in our engagement survey is 6.4 (on a 1–7 scale), suggesting that on average, staff do not exhibit a low engagement score. THL has staff policies against harassment and discrimination. A few staff report that they themselves have experienced harassment or discrimination at their workplace during the last twelve months, while a few more report to have witnessed harassment or discrimination of others. About a third of these people agree that the situation was handled appropriately. See all other related policies in the table below.

Because of confidentiality, THL wasn’t able to comment on any specific instances of reported discrimination or harassment. However, they note their process for handling complaints is transparent, and that they have hired independent investigators whose investigations yielded no findings of harassment or discrimination.

Policies related to representation/diversity, equity, and inclusion (R/DEI)

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics/conduct | |

| A written statement that the organization does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels, up to and including the board of directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| Documentation of all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

Our Assessment

We are concerned that a few staff report that they witnessed instances of harrassment or discrimination that they felt were not handled appropriately. THL reported handling these concerns according to their policies and procedures. We also positively note that (i) THL is transparent toward external stakeholders, (ii) staff generally agree that leadership guides the organization competently, (iii) THL’s leadership is aware of potential challenges regarding imbalanced power relations between developed and developing countries and has addressed them appropriately, and (iv) team members are generally engaged and satisfied with their job.

On average, our team considers advocating for welfare improvements to be a positive and promising approach. However, there are different viewpoints within ACE’s research team on the effect of advocating for animal welfare standards on the spread of anti-speciesist values. There are concerns that arguing for welfare improvements may lead to complacency related to animal welfare and give the public an inconsistent message—e.g., see Wrenn (2012). In addition, there are concerns with the alliance between nonprofit organizations and the companies that are directly responsible for animal exploitation, as explored in Baur and Schmitz (2012).

The weightings used for calculating these country scores are scale (25%), tractability (55%), and regional influence (20%).

We don’t believe that the number of individuals is the only relevant characteristic for scale, and we don’t necessarily believe that groups of animals should be prioritized solely based on the scale of the problem. However, number of animals is one characteristic we use for prioritization.

We estimate there are 10 quintillion, or 1019, wild animals alive at any time, of whom we estimate at least 10 trillion are vertebrates. It’s notable that Rowe (2020) estimates that 100 trillion to 10 quadrillion (or 1014 to 1016) wild invertebrates are killed by agricultural pesticides annually.

For arguments supporting the view that the most important consideration of our present actions should be their impact in the long term, see Greaves & MacAskill (2019) and Beckstead (2019).

ACE believes that language can have a powerful impact on worldview, so we avoid terms such as “broiler chicken,” “poultry,” “beef,” etc., whenever possible. “Broiler chicken,” in particular, defines these birds in terms of their purpose for human consumption as meat. This can contribute to a lack of awareness about the origins of animal products and could make it difficult for consumers to understand the effects of their food choices. That being said, many of the charities that ACE evaluates use this language for strategic reasons in their campaigns, so we will use the term “broiler chicken” when referring to chickens raised for meat for the sake of simplicity.

The European Chicken Commitment is a six-point pledge that requires food companies to improve welfare standards for all chickens in their supply chain by 2026.

To be selected for evaluation, we require that a charity has a revenue of at least about $50,000 and faces no country-specific regulatory barriers to receiving money from ACE.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost effectiveness.

The Better Chicken Commitment is a pledge that requires food companies to meet improved welfare standards for broiler chickens in their supply chain by 2024 and 2026.

Clark and Wilson (1961), as cited in Rollag (n.d.)

Examples of such social identity characteristics are: race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, and genetic information.

Harassment can be non-sexual or sexual in nature: ACE defines non-sexual harassment as unwelcome conduct—including physical, verbal, and nonverbal behavior—that upsets, demeans, humiliates, intimidates, or threatens an individual or group. Harassment may occur in one incident or many. ACE defines sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances; requests for sexual favors; and other physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors of a sexual nature when (i) submission to such conduct is made explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment; (ii) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting the targeted individual; or (iii) such conduct has the purpose or effect of interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

ACE defines discrimination as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of or hostility toward an individual on the basis of certain characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries), such as race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, or genetic information.