Animal Advocacy in India

- Introduction

- Methods

- Animal Agriculture in India

- Current State of the Farmed Animal Advocacy Movement in India

- Opportunities for Effective Animal Advocacy in India

- Challenges to Effective Animal Advocacy in India

- Conclusion

- Questions for Further Consideration

- References

We’d like to thank Victoria Schindel for contributing substantially to the research and writing of this report. We’d also like to thank Lakshmi Venkataraman, Shubhobroto Ghosh, and Harshdeep Singh for providing external feedback, and the following individuals for participating as interviewees: Amruta Ubale, N.G. Jayasimha, Alokparna Sengupta, Varun Deshpande, and Prashanth V.

Introduction

In order to reduce animal suffering in India, it’s necessary for the global effective animal advocacy (EAA) community to understand the local context, considering at once the political, economic, and cultural factors that could lead to challenges and opportunities for EAA. Prior to this research, ACE’s understanding of India’s local context was relatively limited—this report outlines our findings, as well as important questions for further consideration. We hope that this report will serve as a resource for groups aiming to undertake high-impact animal advocacy in India, especially international organizations lacking a nuanced understanding of the local context.

Demographics & Economy

India has a population of about 1.3 billion people, which sources estimate is growing steadily between 1.15% and 1.17% per year.1 According to the World Bank, 34% of India’s population live in urban areas, but official statistics likely under-represent the true size of the urban population because they don’t take into account “hidden” areas with urban characteristics, such as improvised settlements on the peripheries of cities.2 In addition to rapid population growth and urbanization, India is experiencing rapid economic growth and an expanding middle class3 with a growing interest in animal-based, processed, and value-added foods.4

India is the seventh largest economy in the world,5 of which animal agriculture and farming are an important part. Around 20.5 million people are employed in the livestock6 sector which contributes up to 16% of income for small rural farms and provides livelihood for two thirds of the rural population.7 The Indian dairy industry is of particular importance—it was estimated to be worth $70 billion as of 2014/15, accounting for 67% of the value of livestock agriculture.8

India has a fairly average per capita consumption of dairy products when compared globally,9 with consumption appearing to vary substantially within the country.10 Consumption of milk has been steadily increasing in recent years, from 93.8 lbs (42.6 kg) per capita in 2013 to 108.8 lbs (49.3 kg) per capita in 2018.

Consumption of meat in India is remarkably low—the Indian Council of Agricultural Research estimates per capita consumption to be around 12.13 lbs (5.5 kg) per year, compared to a global average of 88.19 lbs (40 kg) per year.11 However, domestic demand for meat is expected to rise to three times its current level by 2050, driven by population increase, income growth, and urbanization. The Indian government is encouraging this rise by recommending increased animal product consumption to reach an intake of 0.7 oz (20 g) of animal-based protein per day.12

Animal Welfare Laws

India has some of the strictest and most extensive animal welfare rules, acts, and laws in the world. That said, most laws are outdated and rarely implemented. In theory, these regulations appear to be quite progressive. For example, the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act of 1960, the Transport of Animal Rules of 1978 (amended in 2009), and even the Constitution all contain language that aims to protect farmed animals from cruelty.13 However, the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act of 1960, which is the main animal welfare law in India, has not been updated since it was created. As a consequence, the fine for violating the act is only 50 rupees, which is the equivalent of about 1 USD.14 While Animal Equality India, HSI/India, and several other organizations have been working towards legal revision, they have not yet made substantial progress.

Religion & Politics

According to the CIA World Factbook, in 2011, the Indian population was estimated to be distributed as follows: 79.8% Hindu, 14.2% Muslim, 2.3% Christian, 1.7% Sikh, with the rest being unspecified or other. It’s also worth noting that the world’s largest concentration of Jains live in India, though they only represent a very small portion of the population.15 While religious conflict is long-standing in India, there appears from media reports to have been a rise in religious tensions across the country since 2014.16 In 2016, Pew Research center identified India as the country with the highest level of social hostilities involving religion in the world.17

India has an electoral democracy, which is dynamic and competitive, featuring a multiparty system at the state and federal levels.18 Elections are overseen by the Independent Election Commission for India and are described as “free and fair.” However, the financing of political parties is opaque and corruption involving politicians and civil servants is common.19 While India is a secular nation, the current prime minister, Narendra Modi, is a member of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, Indian People’s Party), a pro-Hindu political party. Since India is a parliamentary democracy, the prime minister acts as the head of government.20, 21

Reports by Freedom House and GAN Integrity report that petty corruption, bribery, and facilitation payments are commonplace within India’s public administration, especially in the police and the lower levels of the judiciary.22 There are some restrictions on freedom of assembly and association, although peaceful protests are able to take place. Non-governmental organizations are generally able to operate, but can face threats, harassment, excessive police force, and occasional violence.

Methods

We conducted a literature search to find information regarding animal advocacy in India using Google, Google Scholar, Ecosia, and the Animal Charity Evaluators research library. In addition, we spoke with staff members of established animal advocacy and dietary change organizations in India to better understand their work and the progress they have made. We interviewed staff from Animal Equality, The Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO), Humane Society International (HSI), and The Good Food Institute (GFI). These organizations were selected based on a systematic search for advocacy groups in India, and contacts that ACE already had from previous work. All staff interviewed were located in India. Our selection process resulted in an inclusion of more international charities headquartered outside India than charities that originated in India; this sample is unlikely to be representative of all animal advocacy organizations doing work in India.

Animal Agriculture in India

Why Farmed Animals?

It’s our view that focusing on farmed animals is an effective strategy to reduce nonhuman animal suffering in India. While animal exploitation for other purposes (research, entertainment, etc.) merits action, it appears that farmed animal suffering is larger in scale and more neglected in India than other types of animal exploitation and/or suffering.23 For example, according to Alokparna Sengupta of HSI/India, of the astounding 20,000 to 30,000 animal advocacy organizations operating in India, more than 90% focus their work on protecting street dogs.24

Animals used in research also seem relatively less neglected than farmed animals: Multiple media sources have reported a ban on cosmetic testing and imports of cosmetic products tested on animals,25, 26 while medical schools and institutions also appear to be moving away from animal testing.27 Meanwhile, farmed animal suffering remains relatively neglected given it’s large scale (see Figure 1) and potential tractability.

| Type of Animal | Number of Live Animals28 (2017) |

| Buffaloes | 113,329,671 |

| Cattle29 | 185,103,532 |

| Chickens | 783,269,000 |

| Goats | 133,347,926 |

| Pigs | 8,800,350 |

| Sheep | 63,068,632 |

| Total | 1,286,919,111 |

Figure 1. Total number of live farmed land animals in India in 2017. Data from FAOSTAT, 2019

India has a very high percentage of vegetarians compared to other countries and accounts for less than 2% of the world’s meat production.30 In India’s 2015–2016 National Family Health Survey, people between the ages of 15 and 49 from various regions of India self-reported their dietary habits, among other factors. The report estimates that 29.9% of women and 21.6% of men amongst India’s 1.35 billion population are vegetarian.31 We are unsure of the accuracy of this data given people’s tendencies to under-report their consumption of meat32 and India’s complex regional, social, and religious division. With such great variation in dietary behaviors across geography, class, and gender, generalizations are difficult to make.33

We are uncertain as to the percentage of people with a vegan diet, but given the cultural and nutritional significance of dairy in India, the number of vegans is presumably very low in proportion to the number of vegetarians.34

While public discourse tends to highlight that the proportion of non-vegetarians in India is rising,35 some argue that this isn’t actually the case. For example, in our interview with HSI/India, N.G. Jayasimha stated that the per capita increase is “more likely the result of long-standing meat-eaters simply eating greater quantities of meat over time, rather than long-standing vegetarians starting to eat meat.”36 He noted that people aren’t uniformly incorporating meat into their diets as they become wealthier; rather, meat eaters are increasing their consumption. Amruta Ubale of Animal Equality also pointed out that meat-eating Indians are increasing their consumption.37 She pointed to growing disposable incomes as well as media and corporate influence from Western countries as some of the causes.

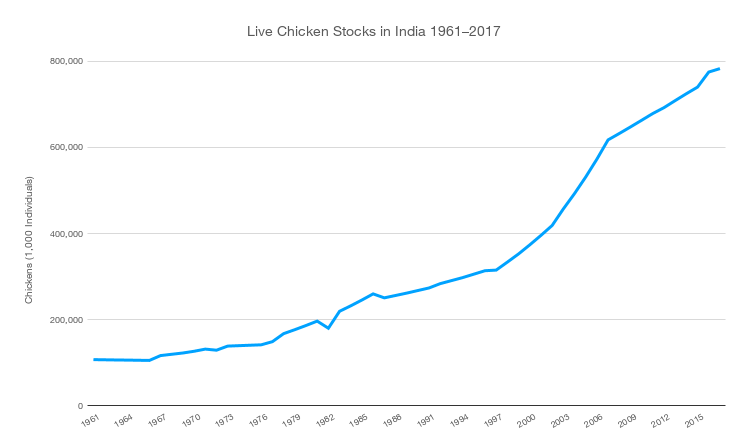

The primary type of meat being consumed in India has shifted away from red meat toward chicken and seafood.38, 39 Due to the very small yield of chicken and fish meat per animal slaughtered as compared to larger farmed animals, this increased demand is leading to a dramatic rise in the number of animals being slaughtered for food (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of live chickens in India from 1961–2017. Data from FAOSTAT, 2019

In general, the “productivity” of animals (i.e., the yield of meat, milk, and eggs) in India is very low. Yields remain relatively low for a variety of reasons: These include (i) animals being raised for other purposes such as milk production, (ii) animals being improperly fed, and (iii) animals being slaughtered at a young age.40, 41 The Indian government reportedly wants to increase the productivity of animals through “carefully planned breeding, feeding, and management programs” in order to meet the growing demand for meat.42

Fisheries and Aquaculture

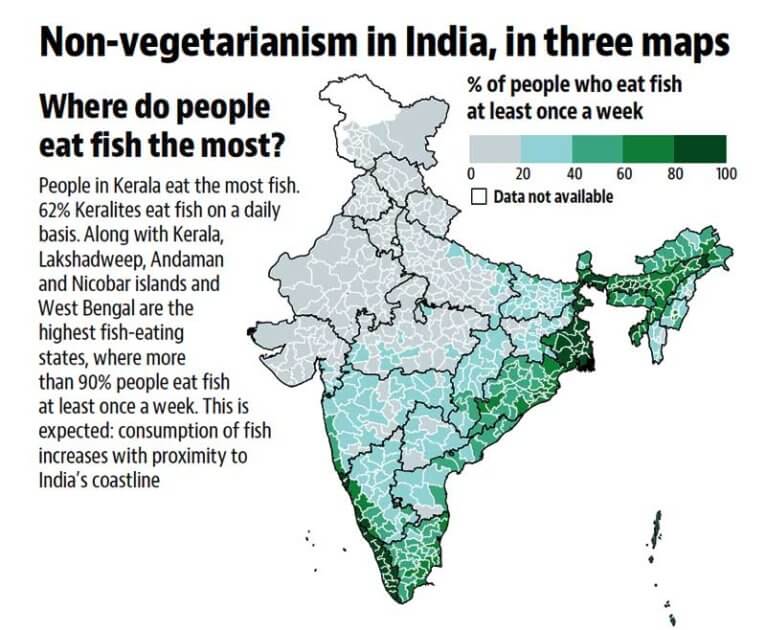

In India, per capita consumption of fish is higher than per capita consumption of land animals.43 Consumption varies drastically by region: fewer than 20% of northern India residents reportedly eat fish on a weekly basis, while more than 40% do so in the southern and eastern coastal regions.44 Overall, fewer than 7% of Indians consume fish on a daily basis.45 Men are somewhat more likely than women to eat fish, as are those residing in urban areas as opposed to rural areas. The consumption of fish has been steadily increasing over time, from an average of 4.4 lbs (2 kg) per person annually in 1961 to nearly 13.2 lbs (6 kg) in 2013.46, 47 This trend toward eating more fish has increased the total number of animals farmed for food.48

Figure 3. Where do people eat fish the most? Image from Hindustan Times

The fish sector has seen dramatic growth in Asia, particularly in India, which was reported to be the seventh largest exporter of fish products in 2014.49 The FAO estimated that 10.16 million metric tons of fish were produced in the region in 2015, including 3.59 million metric tons from the marine sector and 6.57 million metric tons from the inland sector. This has been estimated to represent between 2.98 and 15.49 billion fishes.50 In 2012, the Indian government set the goal of doubling fish availability and production in the Northeastern regions by 2020.51 Government efforts to boost aquaculture production continue as demonstrated by a 2019 budget proposal which aims to create a separate department of fisheries, among other things.52

The majority of producers in India do not conform to the Aquatic Animal Health Code, which “provides standards for the improvement of aquatic animal health worldwide. It also includes standards for the welfare of farmed fish and use of antimicrobial agents in aquatic animals.”53 Sengupta of HSI/India told us that “[c]urrently, aquaculture is mostly unregulated, and to the best of our knowledge, there are no animal welfare organizations in India working on aquaculture. We plan to begin primarily with research before moving on to legal or legislative interventions.”54

Chickens

In addition to being affordable, chicken products have a reputation for being a healthy source of protein in India.55 This is an especially important consideration in a nation experiencing both malnourishment and a rise in obesity.56 Indian state governments have been promoting the use of more eggs in public schools as a means to address these public health issues. Meanwhile, eggs are often presented as a healthy food in the media,57 posing a challenge to groups aiming to slow India’s rising consumption.

Broiler Chickens

India is the fourth largest producer and consumer of chicken meat globally,58 with more than 780 million chickens living there today, an estimated 274 million of whom are broiler chickens.59, 60, 61 Total production of chicken meat increased by approximately 20.81% between 2007 and 2012,62 and the industry continues to grow rapidly in financial value at 12%–15% per year.63 While some of the chicken meat produced in India is exported to neighboring countries, most is consumed domestically where demand has been growing.64 In 2018, Faunalytics reported that per capita consumption has increased dramatically from 1.3 lbs (0.6 kg) per year in 1996, to 4.4 lbs (2.0 kg) per year in 2018. They predict it will rise to 5.1 lbs (2.3 kg) per year by 2026.65

Intensive confinement models have been used in India for chicken and egg production since the 1990s,66 and the industries are becoming increasingly vertically integrated.67 These new production methods have lowered prices, making chicken meat an increasingly accessible source of protein. In particular, there seems to be a growing interest in processed chicken meat. As of 2015, demand was growing at 15%–20% per year, attributable in part to urbanization which fuels a demand for industrially produced, processed, and fast foods.68

Eggs

At present, India is reportedly the third largest69 and fastest growing egg producer in the world.70 The country produced around 84 billion eggs in 2017,71 and the industry is said to be growing at 6%–8% per year.72 Roughly 80%–90% of eggs are produced by commercial, industrialized farms operated by big-brand companies.73 While some eggs are exported, the vast majority are destined for domestic consumption.74

The government has been encouraging the consumption of eggs; for instance, India’s Mid-day Meal Scheme aims to address public health and increase school attendance by encouraging the use of eggs in schools. The politicisation of eggs has fallen under criticism from Animal Equality, who have highlighted the health, environmental, and ethical concerns surrounding this practice.75 However, eggs are often still presented as a healthy food in the media.76

Cows, Buffaloes, Sheep, and Goats

India has the largest total cow population in the world—in 2018, there were 305 million cows in the country.77 India also has the world’s largest buffalo population, the second largest population of goats, and the third largest population of sheep.78

Meat

Bovine animals are not farmed specifically for meat in India, but buffaloes are sent to slaughter when they are no longer able to be used for milk production or for reproduction.79 Around 4.2 million metric tons of beef are produced annually in India, of which 2.4 million metric tons are consumed domestically with the remaining 1.8 million metric tons being exported.80 Buffalo meat is the second largest commodity exported from India—it is exported primarily to the Middle East and South Asian countries.81 The export of cow meat is illegal.82

India is also the second largest producer of goat meat in the world, accounting for 11.34% of total production.83 Goat and sheep meat is marketed in villages by slaughtering a small number of animals once or twice a week, whereas in large towns and cities, slaughtering is said to occur mostly in abattoirs or slaughterhouses—many of which are illegal.84 It is unclear exactly what proportion of goats and sheep in cities are slaughtered roadside, though the practice seems to be somewhat commonplace.85

Dairy

India is the largest producer and consumer of dairy in the world,86 followed by the United States and China—in 2013, India produced 17.6% of the world’s milk.87 India’s dairy industry provides jobs for millions of people. Ubale of Animal Equality told us that the livestock sector in India is not vertically integrated and there is a “co-operative model of dairy, whereby big-brand companies collect their milk from a number of smaller, rural farms.”88 The National Cooperative Dairy Federation of India (NCDFI) was registered in 1970 to promote, coordinate, develop, and facilitate the working of the dairy industry as cooperatives. According to the NCDFI website, there are 1.63 million dairy farm members across India.

According to the Indian Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, 48% of total milk produced is either consumed at the producer level or sold to non-producers in the rural area, with the remaining 52% sold to consumers in urban areas.89 Demand for milk in India increased from an average of 8.22 oz (233 g) per day per person in 2010, to 12.38 oz (351 g) per day per person by 2017. This is thought to be due to urbanization, increased consumer interest in high-protein diets, and increased consumer awareness of value-added dairy products.

World Animal Protection reports that there are up to 50 million cows suffering on dairy farms in “unacceptable conditions” such as poor quality housing and confinement, leading to painful health problems and shortened life spans.90 The Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO) carried out undercover investigations in 451 dairies across 10 states as part of its “End Exploitative Dairies” campaign and discovered that (i) 79% of dairies keep animals tethered 24 hours a day, and (ii) 47% of dairies use oxytocin, a hormone which induces labor pains, to increase milk production.91

It is prohibited to slaughter dairy cows in all states except Kerala and some parts of North-East India.92 As a result, farmers will often abandon unproductive dairy cows when they can no longer afford to feed them.93 Abandoned, unproductive cows sometimes end up in gaushalas or cow shelters, of which FIAPO estimates there are approximately 4,000 operating under varied management practices.94

Current State of the Farmed Animal Advocacy Movement in India

Advocacy for farmed animals in India is neglected relative to the number of animals farmed for food. Currently, the vast majority (around 90%) of the 20,000–30,000 animal groups in India seem to focus on street dogs, with a significant number of groups also focusing on the protection of cows for religious purposes.95 Groups in India dedicated to advocacy for farmed animals include: Humane Society International,96 Animal Equality,97 The Good Food Institute, The Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO),98 People For Animals, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), Mercy For Animals (MFA), Vegan Outreach,99 SHARAN,100 and World Animal Protection.101 The farmed animal advocacy work undertaken in India is focused on both campaigning for welfare reforms on farms and advocating for dietary change, particularly around consumption of dairy. Welfare reform work is usually done through the executive or judicial branches of government, not through corporate campaigns targeting companies.102 Much of this work is supported by insights gained from undercover investigations.

Undercover Investigations

Animal Equality recently conducted an investigation of the broiler chicken industry103 and PETA and World Animal Protection have conducted investigations of dairy farms.104 FIAPO has also investigated dairy farms as well as gaushalas in recent years.105 Mercy For Animals received a grant from Open Philanthropy Project in 2017 which was intended to help support undercover investigations, corporate campaigns, research, and policy-related campaign activities in India in 2017–2019,106 so it’s possible that they will publish their investigations in the near future.

Ubale of Animal Equality told us that “[t]he information gathered from investigations forms the backbone of all of our lobbying efforts, proposals, education, and even corporate outreach. Often, I see educational efforts where the videos being shown are from Western animal rights organizations. This creates a barrier between the educators and their audiences because audiences don’t see the immediate connection to India.”107

Welfare Reforms

India has a set of strong laws protecting animals. Welfare reforms to create new laws and implement existing legislation are one of the main ways in which groups advocate for farmed animals. For example, FIAPO recently launched a campaign through which they persuade state governments to improve the conditions on dairy farms. HSI/India and People for Animal also collaborate with the government for legislation to improve welfare. Likely with participation from other advocacy groups, they have reportedly successfully ended the practice of forced moulting, in which egg-laying hens are starved for more than two weeks to increase profitability of flocks. They’ve also campaigned extensively against battery cages, and in 2013 they persuaded the Animal Welfare Board of India, as well as governments in 26 of 29 states across the country, to declare battery cages illegal.108

Some groups focus specifically on implementing existing laws. For example, FIAPO has a campaign called “Stop Slaughter Cruelty” in which they expose how the slaughter industry violates animal welfare laws, and then use the footage to pressure governments to enforce existing rules.109 The campaign has developed a network of 174 activists in 12 cities. Some examples of campaign successes include the regulation or closure of 557 illegal roadside meat shops through collaboration with government regulatory agencies; the filing of 1,236 complaints against illegal meat shops; and the education of 237 meat shop owners on understanding animal cruelty and following welfare regulation.110 These achievements demonstrate the opportunity to work with governments to create measurable change for animals in India.

In addition to the successes achieved by FIAPO, Jayasimha of HSI/India told us that they “made the case with the Ministry of Finance and the National Rural Development Agricultural Bank parties to ensure that financing for industries that use intensive confinement will stop. By doing so, [they] wanted to ensure that intensive confinement would not be economical by halting access to funding.” Jayasimha noted that funding control, be it through debt or investment, may be one of the most promising opportunities for implementation in India.

Campaigning for welfare reforms in India is generally approached through legislative rather than corporate outreach. This is because the Indian animal agriculture system is generally unregulated, with the majority of farming taking place on a small scale. Also, there is an absence of large retail chains, which means corporate outreach is generally not tractable or even possible.111

Dietary Change Advocacy

In addition to campaigning for welfare reforms, farmed animal advocates in India also seem to focus on reducing consumption of animal products—Vegan Outreach, PETA, MFA, and FIAPO have all been involved in these kinds of campaigns. For example, FIAPO is running several individual and institutional outreach campaigns. “Living Free” is a campaign in which FIAPO creates networks of volunteers across the country who encourage and support people to adopt a plant-based lifestyle. In 2018, “Living Free” reached 77 cities across India and held 1,453 events. “Don’t Get Milked” is an aggressive media campaign which works in collaboration with the “Living Free” campaign to encourage consumers to stop consuming dairy and other animal products by exposing them to the cruel realities of the dairy industry. To date, the “Don’t Get Milked” campaign has had 1,058 people sign up for the 21-day compassion challenge. The challenge is for those who pledge to go vegan for a minimum of 21 days and in turn forgo all animal products from their diet. Evidently, these types of programs have had some degree of measurable success.

Opportunities for Effective Animal Advocacy in India

Strong Animal Welfare Laws

Of all of the species who are theoretically protected under India’s laws, cows receive the highest degree of protection due to their symbolic significance in Hindu religion and culture. According to Article 48 of the Constitution of India 1949, it is explicitly prohibited to slaughter cows.112 While this Article is a Directive Principle of State Policy (DPSP), meaning it is not justiciable and the government cannot be made to enforce it through the court, it highlights the cultural significance of the sacred cow.113 In some states, it is explicitly illegal to kill cows, but it remains legal in a few. Regardless, consumption of beef from cows seems to be quite low overall.114

As part of their continued efforts to protect cows, the Indian government attempted to enforce a ban on beef in 2017. The ban was later suspended by the supreme court—a decision which led to protests and controversy between religious groups, as reported by the media.115 Several protests which garnered particular media attention and controversy were the public slaughter of a young cow and the organization of beef festivals across the country. Currently, the ban is enforced at the state level, meaning that states have the choice to enforce it.

Considering India’s high dairy consumption, efforts to reduce dairy cows’ suffering is relatively neglected: Advocacy and laws tend to focus almost exclusively on preventing slaughter, rather than ensuring a high quality of life. FIAPO is already working with state governments to issue stricter guidelines on dairy cow welfare, but it seems like there is still an opportunity for further advocacy in this area.116

Despite complicated political and religious context, it seems as though these animal protection laws can be viewed as an opportunity to help improve the conditions of farmed animals in India, and several of the groups we spoke to are taking measures to this end.

Strong Public Support for Improved Welfare Standards

There seems to be strong public support for improving the welfare standards of dairy cows and buffaloes in India. In 2016, World Animal Protection surveyed 3,000 people and concluded that 90% of them believed that cruelty to animals on dairy farms is unacceptable.117 In addition, 75% of people said they would be willing to pay 5%–10% more for products that came from farms with better standards of welfare. With such a large number of animals being used for dairy production, this reported public support for welfare reforms could pose a great opportunity to reduce the suffering of millions of animals. Some groups are already working in this area: The FIAPO “End Exploitative Dairies” campaign is working to introduce licensing rules at the national level, under the Registration of Cattle Premises Rules, as well as at the state level.118

In general, India is known for ahimsa, the principle of nonviolence toward all living beings.119 Ubale of Animal Equality told us that nonviolence principles are present in “not only the Hindu scriptures, but nearly every active religion or caste system in the country.”120 Accordingly, it seems plausible that working to raise awareness of animal suffering on farms and in slaughterhouses could be used as an appeal to both the general public and the government.

Development of Plant-Based and Cultured Food Technology

India is home to some very strong and renowned research institutions which could play a significant role in the development of cultured meat technology. For example, HSI/India and GFI are already working with The Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) in Hyderabad to develop a prototype.121 The CCMB has since partnered with the National Research Centre on Meat (NRCM) and taken on a project to develop lab-grown mutton and chicken with funding from the department of biotechnology.122 What’s more, the Institute of Chemical Technology (ICT) Mumbai and The Good Food Institute (GFI) have recently partnered to set up the world’s first government research center for cultured meat development, due to open in 2020.123 With India’s growing consumption of chicken, fish, eggs, and dairy, cultured meat technology is likely an excellent opportunity to replace traditional animal products from people’s diets.124

There is very little competition at this stage for companies working towards innovative alternatives to meat, dairy, and eggs. GFI and Good Dot, a food tech startup in India, seem to be two of the only organizations working in this field. Goodmylk is another innovative company focusing on plant-based alternatives to milk, yogurt, and butter. In order to supplement the institutional and corporate outreach that groups like Animal Equality are doing in India to reduce meat consumption, it will be necessary to offer alternatives to meat, dairy, and eggs. Ubale of Animal Equality highlighted this when she stated that “even though most companies tend to agree with our advice, there is a big shortage in the supply of the kinds of plant-based products they are now interested in. This is especially the case with regard to vegan milk alternatives, egg replacements, and clean meat.” Prashanth V. of FIAPO also reported that the plant-based food market is growing and that very few have started to tap into this market, meaning there is a great opportunity to increase the availability of these products and market them to corporations and individuals.125

It’s possible that companies will have more success marketing plant-based and cultured meat and eggs than dairy. As mentioned by Jayasimha of HSI/India, the consumption of dairy serves religious functions that meat does not serve. Milk is associated with communion ceremonies and other religious activities—advocates should be aware of this when producing and marketing plant-based alternatives to dairy.126

Health Concerns and Environmental Issues

Alongside the primary concern of reducing animal suffering, there are a number of compelling health and environmental concerns regarding the increased consumption of animal products in India. As Indian diets have diversified since the 1980s away from cheaper foods such as cereals and towards more expensive foods such as meat and milk,127 the country has seen a rise in obesity and associated cardiovascular disease,128 as well as a rise in diabetes.129 India’s population is now simultaneously struggling with obesity, undernutrition, and micronutrient deficiencies.130

In addition to the health concerns associated with animal-based products,131 Low EPI scores are particularly indicative of the need for a country to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and protect biodiversity.

Some advocacy groups are already leveraging existing health and environmental concerns to advocate for reduced animal product consumption. Varun Deshpande of GFI/India expressed optimism about the government’s receptivity to cultured meat, noting that “[t]he sector is […] very attractive for the government from the perspective of sustainability, promoting agricultural income and entrepreneurship, and giving a fillip to technology development, so we decided to focus on both scientific institutions and government agencies.”132 PETA India has also taken the environmental angle in their advocacy: They published information about the harmful impacts of intensive animal agriculture on the environment, drawing attention to the inefficiency of feeding grain to livestock.133

Similarly, HSI/India has produced a fact sheet which explains the links between animal agriculture and greenhouse gas emissions, particularly methane.134 The fact sheet notes that climate change poses “significant challenges” to agriculture in India, and draws attention to the negative impacts of factory farms on the environment, public health, and rural livelihoods. For example, it outlines how soil on factory farms are unable to absorb all the manure that is produced by large numbers of confined animals, which then becomes a pollutant. This document also points out that enteric fermentation135 is responsible for approximately 49% of India’s methane emissions. Due to the relatively short atmospheric lifespan of methane compared to carbon dioxide, reductions in the number of dairy cattle and buffaloes presents an opportunity to mitigate the more immediate impacts of climate change. According to one of our sources, awareness of this topic is still very low in India.136

Challenges to Effective Animal Advocacy in India

Difficulties Enforcing Animal Welfare Laws

While India does have strong laws protecting animals, there is still a wide gap between those laws and the actual treatment of animals. For example, according to Indian law, animals cannot be legally slaughtered outside of licensed slaughterhouses, but this law is not enforced or regulated for the slaughter of chickens or goats. Animals are regularly slaughtered in live markets, and most of the slaughterhouses that do exist are not legally registered.137, 138

Barriers to Implementation

Ubale of Animal Equality attributes this lack of enforcement in part to the absence of governmental committees at the city, district, and national level.139 For example, despite existing welfare laws, there is a lack of domestic regulating authority to maintain hygiene, processing, and transporting of chickens and hens. Especially as the industrialization of animal agriculture leads to increased animal and environmental concerns,140 there is a great need for regulatory committees to ensure that laws are being enforced.

What’s more, some laws cannot be implemented due to high costs or other environmental factors. For example, most broiler chicken and egg farms lack climate control and quarantine mechanisms,141 and while large, controlled-environment integrators do exist, they cannot be widely adopted because of high costs and unreliable power sources.142 The result is that animals live in unsanitary conditions that likely cause them to suffer. In general, implementing higher welfare standards is probably associated with higher costs, making it difficult for farms that are lacking the resources to change their standards.

Government Prioritization of Human Rights and Poverty Issues

It seems that India’s need to address human rights, poverty, and economic development is a major barrier to EAA in India. According to the World Bank, 270 million Indians—approximately 20% of the total population—live in poverty.143 Those in poverty lack access to basic services such as sanitation, running water, and electricity. They spend a higher percentage of their income on food, fuel, and lighting than the non-poor and are more likely to be employed in temporary or part-time labor. The World Bank reports that illiteracy is as high as 45% among India’s poor and that the rate of high school completion is low. Sources also state that in 2018, 70.6 million Indians—or around 5% of the total population— were living in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than $1.90 a day. 144 Those in extreme poverty commonly lack access to food, shelter, and clothing.

As noted above, malnutrition remains a significant problem in India. With around 195 million people experiencing malnutrition, the country accounts for one quarter of total world hunger. Four out of every ten children suffer from chronic undernutrition or stunting, conditions which have negative impacts on learning capacity, school performance, future earning potential, and risks for chronic diseases.145

The Indian government has a large number of food security and anti-poverty programs, including finding ways to increase farmers’ income, but there are still a number of inclusion gaps, with women and girls particularly disadvantaged. In addition, India now faces new challenges such as mitigating the impacts of climate change, land degradation, and shrinking biodiversity.146 India’s development priorities align very closely with a number of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, with a particular emphasis on rural electrification, sanitation, improving access to housing, clean and renewable energy expansion, universal elementary education, and skills development.147

It’s our understanding that these widespread development challenges could significantly impact the progress the animal advocacy movement is able to make in India. It seems likely that groups focusing on animal protection issues could risk appearing anti-developmental or anti-national,148 while those who do may be met with indifference or apathy. Indeed, Ubale of Animal Equality told us:

“From our multiple experiences bringing proposals before the government in relation to animal rights violations, we have found that the government does not see animal welfare as a significant priority. This may be because the Indian government deals with so many cases of human rights violations. When considered alongside human rights issues, animal rights issues may appear diminished in terms of importance and urgency.”149

That being said, an opportunity presents itself for animal advocates to frame reduced meat consumption and production as a potential remedy to some of the abovementioned issues.

Government Restrictions

Foreign Funding

While Indian organizations can accept foreign funding, there are strict regulations that make it difficult to raise funds efficiently. This is reported to be especially true of foreign NGOs taking a controversial stance that could be perceived as anti-developmental.150 Restrictions include: “reporting and accounting requirements for foreign funding; government approval required for foreign funding; foreign-funded organizations prohibited from carrying out particular activities, and certain types of organizations are prohibited from receiving foreign funding; other restrictions on use of foreign funding.”151 There’s been a recent decline in foreign funding as many organizations were removed from the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act for violating laws such as not reporting their annual reports on funding/spending.152 As a result, it’s important for groups aiming to provide funding to Indian advocacy organizations to consider whether they are still registered under the act.

Censorship

Freedom House reports that close relationships exist between politicians, business executives, lobbyists, media personalities, and media outlet owners in India.153 The Constitution of India guarantees freedom of expression, but authorities have reportedly used security, defamation, hate speech, and contempt-of-court laws to curb political criticism in the media. While the internet is generally unrestricted, a nationwide Central Monitoring System was launched in 2013, enabling the authorities to intercept any real-time digital communication without judicial oversight. Overall, it seems like there can be difficulties in accessing government information, and that censorship can be heavy-handed.154

Societal Perceptions

Views of Meat, Dairy, and Plant-Based Foods

India’s population is largely vegetarian, but some advocates have stated that meat is regarded as a status symbol. With India’s economy developing rapidly, the middle class in particular is becoming more prosperous and able to afford more animal products. Sengupta of HSI/India noted that particularly in times of prosperity like now, meat and other animal products can serve as a symbol of wealth.155 Ubale of Animal Equality also noted that eating animal products is “synonymous with luxury” in India, and that people tend to increase their intake of meat and dairy as their disposable income grows.156 As India’s economy is projected to continue to grow, this trend should be considered by animal advocates particularly as they market plant-based or cultured meat.

Unlike meat, dairy is a staple of Indian cuisine.157 Dairy production is an important source of revenue for many people, and it provides protein and sustenance to a country with widespread malnourishment.158 These challenges could theoretically all be addressed with the introduction of price-competitive alternatives to dairy. However, dairy holds an important religious significance for many people in India, and one advocate we spoke to expressed a great deal of uncertainty about consumer acceptance of plant-based dairy. He noted that milk serves many general and specific religious functions, that it is considered the “nectar of life” for many people, and that it is commonly used during communion ceremonies.159 Given it’s cultural significance, it would likely be difficult to get consumers to shift towards plant-based dairy. However, the same advocate noted that plant-based dairy could be impactful if it became convenient in terms of manufacturing, transporting, and selling.

In general, it seems that negative perceptions of plant-based foods may be prevalent in India. Several advocates we spoke with noted that alternatives to meat are not a novel idea to Indians: Due to the high rate of vegetarianism and the affordability of soy, consumers are very familiar with products like soy nuggets and granules, and they are often not fond of them. Sengupta of HSI/India highlighted this issue, and stated that it’s essential to make enticing alternatives to meat that are different from the things people are familiar with in order to increase consumption. She expressed (i) a need for a variety of exciting plant-based meat to enter the market, and (ii) a need for consumer perceptions of plant-based meats to change. Deshpande echoed this sentiment, and highlighted GFI/India’s plans to conduct research into consumer acceptance of plant-based and cultured meat in order to better understand the challenges that are specific to India.160

Societal Exposure to Animal Suffering

It’s important to note that unlike in the U.S. and some other western countries, it is not unusual for Indian consumers to be exposed to animal suffering in their day-to-day lives. This might pose a challenge in terms of raising awareness of animal suffering on farms, since people are already accustomed to seeing animals slaughtered in public markets. Jayasimha of HSI/India pointed out the following:

“It is impossible to walk through any public market without seeing birds or fish being sacrificed, and most people who eat meat have probably seen animals slaughtered. […] People become overly accustomed to the sight of animal suffering. The possibility of shocking people into action through exposure to animal suffering is unavailable to us—people see animal suffering every day.”161

Perceptions of Animal Advocacy

Perceptions of animal advocacy, and nonprofit work in general, seem to be limiting the growth of India’s animal advocacy movement. According to some of our interviewees, people don’t tend to consider animal advocacy a viable career choice. Instead, they perceive advocacy as an admirable activity to engage in during one’s free time or after retirement. Jayasimha of HSI/India noted that he was surprised to find that “even with a great deal of funding, it is still a struggle to find people to hire.” Sengupta also noted that many people might not even know that animal advocacy is a viable career path, and that “it’s possible that prospective workers anticipate, in some cases rightly so, that animal advocacy organizations won’t have measurable goals and objectives, proper feedback, appraisals, bonuses, and so on.”162

Ubale of Animal Equality also highlighted this issue during our conversation, noting that India is behind in terms of getting the right people on board. She pointed out that the country is “known for churning out professionals in areas like engineering and medicine,” and that within that context, it’s “almost an impossible challenge” to find people to work in the nonprofit sector.163 It’s our view that animal advocates in India could benefit from efforts to shift public norms and educate people about the possibilities of pursuing high-impact careers in animal advocacy.164 For example, it could be particularly impactful to implement career counseling across disciplines (law, management, etc.), or to create an accessible online career guide similar to the 80,000 Hours website.165

Cow Protectionism

Cow protectionist or vigilantes are people who support the protection of cows for cultural or religious reasons. They tend to be Hindu nationalists and to strongly oppose the consumption of beef. Media reports suggest that cow protectionists have been engaging in public attacks against minority groups who consume beef, fueling conflict between different religious groups.166 It seems that the majority of attacks have targeted Muslims,167 though Dalits have also historically been discriminated against for consuming beef and working in tanneries.168 It seems that tensions across religious groups are particularly pronounced now that the BJP is taking measures to spread Hindu Nationalism. For example, in addition to the reported rise in cow protectionist attacks, several cities have recently been renamed to reflect Hindu figures or events,169 resulting in opposition from groups and individuals who accuse the government of attempting to erase minority religious and cultural heritage across the country.170

It seems that cow protectionists are problematic for animal welfare and advocacy for several reasons. Among other things, (i) they focus solely on protecting cows from being used for meat with the exclusion of dairy, and (ii) they value cows at the expense of other animals. According to Jayasimha of HSI/India, the majority of cow suffering comes from the dairy industry.171 He notes that these products are cheaper and drive a significant amount of cow farming, so advocates aiming to help cows should not focus exclusively on meat. He also notes that cow protectionists will prevent cow slaughter at all costs, often disregarding the slaughter of other animals, even animals who are similar to cows like water buffaloes. He says that his organization has noticed, anecdotally, that when a fundamentalist Hindu group comes into power in a given state, consumption of beef might decline, while consumption of other small-bodied animals will increase to compensate.172

Finally—and perhaps most importantly for the animal advocacy movement—some advocates have suggested that cow protectionist actions create stigma associated with protecting animals.173 Prashanth V. of FIAPO noted that one of the greatest challenges to effective animal advocacy in India is the perception of animal advocacy as “extreme,” and the religious controversy surrounding meat consumption.174 Sengupta expressed the same concern and noted that for this reason, HSI/India’s messaging focuses mostly on reduction in meat consumption, as opposed to strict elimination. She noted that her organization is careful not to get their message confused with that of right-wing protectionists, and that their social media often stems criticisms from people who accuse them of associating with cow protectionists.

Conclusion

There are a number of promising opportunities for effective animal advocacy in India. It is a great advantage that vegetarianism is already common and accepted in Indian culture, and that meat is eaten in relatively small quantities compared to other parts of the world, as this could lower the barrier to dietary change. In addition, the strong research and development environment in India provides promising opportunities for the growth of the plant-based and cultured food industries. With the large and growing scale of chicken consumption, as well as the high degree of neglectedness of fish welfare, this avenue could be particularly impactful in reducing animal suffering on a large scale.

Religious beliefs and practices present both opportunities and challenges. On the positive side, appealing to the commonly-held principle of ahimsa presents the opportunity to increase support for improved animal welfare on farms and in slaughterhouses. On the other hand, the actions of religious cow protectionists cause animal advocates to appear extreme, which may prevent individuals from pursuing careers in advocacy. It appears that in general, animal advocacy is not viewed as a viable career choice, but this has the potential to change gradually through targeted outreach.

Many of the laws needed to protect animals already exist, and some groups have successfully worked with the government to improve their enforcement. However, the significant and wide-ranging development challenges facing India mean that the government does not generally prioritize animal welfare. If groups are able to highlight the negative health impacts of animal products, advocates may be able to convince the government to rethink policies that encourage increased intake of these foods. Similarly, by presenting the links between industrialized animal agriculture and environmental issues such as pollution and climate change, advocates may be able to persuade the government to adopt agricultural policies that are conducive to better welfare for animals.

Questions for Further Consideration:175

- How can groups work towards improving fish welfare in India?

- Currently, the preferred breed for chicken meat in India is Vencobb, which accounts for 65%–70% of broiler meat, and the preferred breed for layer hens is the Babcock, which accounts for 80% of market share.176 What are the welfare implications of using these breeds?

- How tractable would it be to raise awareness about the existing risks associated with avian influenza outbreaks?177 Since these outbreaks are apparently very common in India, they could potentially deter the public, institutions, and corporations, from supporting the industry.

- How best can policy-makers in India be persuaded to promote plant-based diets for the health of the human population, in the context of widespread poverty and low incomes?

- How can the impact of animal rights work in India be better assessed? (It is hard to assess the impact of different kinds of work—whether institutional or consumer outreach, and even the assessments that are available aren’t always accurate.)

- How can research around crucial issues surrounding animal rights in India be leveraged? (Research/data is crucial to developing future interventions, and in being seen as legitimate in the eyes of the government/industry, and is scarcely available in this sector.)

- How much should animal advocates focus on working at the federal level as opposed to state level (as states legislate on animal cruelty as well)?

- How can farmed animal protection organizations garner support from the thousands of organisations working for street dogs?

- Does the use of floor slaughter and dressing procedures have any impact on animal welfare? What impact, if any, does the lack of proper ante-mortem and post-mortem inspection in unregistered slaughterhouses have on animal welfare?

References

For a list of all of the works cited in this report, see our reference list.

Edit 8/14/2019: Initially, we mistakenly wrote that 400 million people in India are employed in the livestock sector. In fact, only 20.5 million people are.

Edit 12/16/2019: We recently added a new estimate for the number of broiler chickens living in India (274 million). The previous estimate (780 million) included egg-laying hens.

Ernst and Young predicted in 2015 that India’s middle class population will grow from 50 million to 200 million by 2020, and to 475 million by 2030. (Fuller, 2015)

We believe that language can have a powerful impact on worldview, so we avoid terms like “livestock” and “poultry” whenever possible. These terms are likely to contribute to a lack of awareness about the origins of food and could make it difficult for consumers to understand the effects of their food choices. That being said, the FAO data that we draw from in this report categorizes meat in this way, so we will use the term “livestock” when referring to cows, buffaloes, sheep, and goats for the sake of simplicity.

According to the Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries (2018), approximately 70 million rural households in India participate in dairying, half of which involve women playing a vital role. The government argues that engaging more women in the dairy industry is a strategy that will help with their empowerment. Approximately 23% of rural households engaging in dairying (16 million households) belong to a dairy cooperative.

See World Animal Protection (2014) for more information about India’s existing animal protection laws.

A. Ubale of Animal Equality added that “[i]n the 2014 Supreme Court judgement banning performances involving cruelty to bulls, the judges actually addressed this problem, suggesting that the parliament should amend the Act and increase fines. There is a huge opportunity there to make great progress for animal welfare, if we can succeed in increasing fines. So far, however, there has been no concrete action taken to revisit the Act, and so this still presents a significant challenge in enforcing animal protection laws” (personal communication, September 11, 2018).

At this time, ACE is not well-informed regarding the potential role that Jainism could play in effective animal advocacy in India. That said, it seems that the religion frames nonhuman animals as possessing cognitive faculties including memories and emotions, and encourages its followers to live without harming other life forms. We suspect there might be an opportunity for animal advocates to appeal to these beliefs. For more information about Jainism, see Chapple (2001).

For example, “India’s Supreme Court” (2017) reports that “Hindu hard-liners and vigilante groups out to protect cows have been increasingly asserting themselves since Mr. Modi’s government came to power in 2014.”

See Pew Research Center (2016) for a full ranking of the world’s countries based on social hostily. Also see this page to download a pdf of the full report.

We are not intending to suggest that corruption is exclusive to India, or that it is not commonplace in other parts of the world. See GAN Integrity’s archive for accounts of corruption within governments across countries and regions.

In India, the prime minister is granted executive power, while the President’s duties are mostly limited to preserving the constitution and the law. Modi was elected in 2014 after allegedly being heavily backed by the right-wing, Hindu fundamentalist National Volunteer Organization, or Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The President of the BJP, Amit Shah, is affiliated with the RSS, having engaged publicly in the student wing of the RSS before becoming the President of the BJP. What’s more, it’s our understanding that the ideology of Hindutva (“Hindu-ness”) is encouraged by the BJP, causing tensions across the country, as reported by the media.

Since the time or writing this report, India has gone through general elections which resulted in a landslide victory for the BJP. See Dale & Jeavans (2019) for more information.

Lakshmi (2016) estimates that there are approximately 30 million street dogs in India.

A. Sengupta of Humane Society International/India noted that “[m]ost other animal protection organizations don’t take ownership of farm animal welfare as a significant issue. This presents a big challenge because it prevents farm animal protection from being a large enough issue for the public to become invested in it.” (personal communication, September 20, 2018)

This data refers to an estimate of the number of live animals present in the country at the time of enumeration.

We believe that language can have a powerful impact on worldview, so we avoid terms like “cattle” and “livestock” whenever possible. These terms are likely to contribute to a lack of awareness about the origins of food and could make it difficult for consumers to understand the effects of their food choices. That being said, the FAO data that we draw from in this report categorizes animals in this way, so we will use the term. Here, they define “cattle” as “Common ox (Bos taurus); zebu, humped ox (Bos indicus); Asiatic ox (subgenus Bibos); Tibetan yak (Poephagus grunniens). Animals of the genus listed, regardless of age, sex, or purpose raised. Data are expressed in number of heads.”

For an analysis of the issues with using large-scale surveys as sources for diet-related data and a more nuanced representation of vegetarianism in India, see Natrajan & Jacob (2018).

For a more thorough discussion of the nutritional and cultural significance of dairy in India, see the section of this report: “Cows, Buffaloes, Sheep, and Goats.”

For example, Rowland (2017) states that “many are rapidly abandoning their vegetarian diet due to an increased desire for meat.”

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

Open Philanthropy Project Farm Animal Welfare Newsletter, 2017

We are uncertain as to whether low meat yields are applicable to all animals or to some more than others.

Open Philanthropy Project Farm Animal Welfare Newsletter, 2017

For comparison, the average U.S. citizen consumed 15.5 lbs of seafood and/or fish in 2015. (Worland, 2016)

Open Philanthropy Project Farm Animal Welfare Newsletter, 2017

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2016

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

See Shankar et al. (2017) for more information about overnutrition, undernutrition, and nutrient deficiency in India.

United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, 2019

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2019

The main breed of chickens used for meat in India is Vencobb, accounting for 65%–70% of broiler meat produced. (United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, 2016)

During the same time period, the meat production increased in India by 7.33%, 7.84%, 11.66%, and 10.34% for cattle, buffalo, goat, and sheep, respectively. (Indian Council of Agricultural Research, 2015)

See United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (2019) for data relating to production and consumption of chicken meat in India.

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

Vertical integration refers to a business model where steps in production are consolidated. Rather than operating solely as a manufacturer, distributor, or retailer, a company performs tasks commonly carried out by suppliers or trade buyers. (Kokemuller, n.d.)

United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, 2016

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

The United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (2016) projected the production of 84 billion eggs in India for 2017.

United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, 2016

See Animal Equality (2019) for more information about their call for the Indian Government to stop using eggs under India’s Mid-day Meal Scheme. Also see Bhatnagar (2018) which highlights the politicisation of eggs and ensuing controversy.

See, for example, Iyer (2018) and Bhatnagar (2018).

United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, 2019

Animals sent to slaughter when they are no longer able to be used for milk production or reproduction include cows, buffaloes, goats, and sheep. (Indian Council of Agricultural Research, 2015)

For more information about the public health, environmental, and animal welfare concerns regarding roadside slaughter, see Ghosh (2007).

Drawing from FAO data, the Open Philanthropy Project Farm Animal Welfare Newsletter (2017) suggests that more of the milk produced in India comes from buffaloes than from cows.

FIAPO conducted investigations into 179 gaushalas across 17 Indian states and reported that conditions and practices in gaushalas are often little to no better than on dairy farms. (Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations, 2018)

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

See the grant awarded to the Humane Society International/India by Open Philanthropy Project (2017) for: “studies on the impact of factory farming in India and potential policy solutions; staff expansion primarily in the areas of outreach and coalition-building, litigation, and policy; operational costs; and re-grants to grassroots animal welfare groups across India.”

See Animal Equality India’s budget for farmed animal welfare reforms.

See FIAPO’s budget for more information about their programs and allocation of resources.

See an overview of Vegan Outreach’s accomplishments in India.

For an example of their work, see World Animal Protection’s case study of high welfare milk production in India.

See Animal Equality’s undercover investigation of the Indian chicken industry.

See PETA’s undercover investigation of Indian dairy farms.

See FIAPO’s investigation of dairy farms.

See the grant awarded to Mercy For Animals by the Open Philanthropy Project (2017) to support new animal advocacy work in India in 2017.

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

Prashanth V. of FIAPO also told us that “[t]he press and media have played an active part throughout the campaign—both as a tool of building pressure on officials and to educate and inform the general public about the hygiene and safety of the meat they buy. The campaign has held eight workshops for meat vendors where they are taught about the healthy practices, and the laws and rules regarding animal slaughter. To date, the campaign has been covered in 43 publications with a collective readership of approximately 500,000 people” (personal communication, January 29, 2019).

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

For an interesting discussion of cows’ significance in Indian culture and everyday life, as well as the impact that plastic pollution is having on cows, see the 2012 documentary titled “The Plastic Cow” (Vohra, 2012).

The consumption of buffalo meat is relatively common. What’s more, consumption of cow’s meat is likely to be underreported, so there is some uncertainty surrounding the data. For an analysis of the issues surrounding self-reported dietary behaviors in India, see Natrajan & Jacob (2018).

See, for example, Jain (2018) and Setalvad (2016).

N.G. Jayasimha also noted that “cows do not necessarily live comfortable or healthy lives simply because they have been protected from slaughter. Many cows are left in the streets to live on a diet of plastic and other garbage. Finally, another issue lies in the fact that cow protectionists focus almost entirely on meat producers and consumers, but the real problem is found in milk and other dairy. These products are much cheaper and drive a significant amount of cow farming” (personal communication, September 20, 2018).

This is a very small sample size relative to India’s population. More research is needed before we can be highly confident in these results.

Ahimsa is a principle common to Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. The word is Sanskrit for “non-injury” or “non-harming.” (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2019) It is important to note that the word has often been misinterpreted and misused within the animal advocacy movement in the West. For an interesting personal piece on this topic, see “Vegans Demanding Changes to Ancient Religions” (Ganesan, 2015).

Humane Society International, 2018; Good Food Institute, 2019

For more information about India’s potential role in plant-based and cultured meat development, see “Why India is a Priority for Plant-Based and Clean Meat Innovation” (The Good Food Institute, 2018).

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

India’s National Family Health Survey 2015–2016 shows that men with a BMI over 25 have increased from 9.3% to 18.3% in the decade from 2005–2006 to 2015–2016. Women with a BMI over 25 have increased from 12.6% to 20.6% in the same time period. Overall rates of obesity in urban areas are almost twice the rates in rural areas. (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2015)

For examples of health problems associated with excessive animal product consumption, there is concern about the environmental impacts of animal agriculture in India and globally: India was ranked at the bottom of the list of countries in the 2018 Environmental Performance Index (EPI). ((Environmental Performance Index, 2018

“Enteric fermentation is fermentation that takes place in the digestive systems of animals. In

particular, ruminant animals (cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, and camels) have a large “fore-stomach,” or

rumen, within which microbial fermentation breaks down food into soluble products that can be

utilized by the animal.” (Environmental Protection Agency, n.d.)Ubale noted that “[a]ccording to Indian law, animals must only be slaughtered in licensed animal slaughterhouses. This is blatantly violated, however, when it comes to both chickens and goats […] There are so many slaughterhouses in India that I couldn’t even give you the exact number off the top of my head. I do know for certain, though, that the majority of them are illegal. I think this shows that the government doesn’t take illegal animal farming practices very seriously” (personal communication, September 11, 2018).

According to the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (2015), there are 4,000 registered public slaughterhouses in India, in addition to an estimated 25,000 unregistered slaughterhouses. Registered slaughterhouses typically only have basic facilities and use floor slaughter and dressing procedures, while unregistered premises lack proper ante-mortem and post-mortem inspection. The Indian government is focused on improving slaughterhouses—the National Mission on Food Processing and National Livestock Mission (NLM) are designed to address issues related to the modernization of existing abattoirs, improving safety and hygiene, and the consideration of animal welfare.

Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend, 2017 (Retrieved from https://www.rvo.nl/sites/default/files/2017/05/poultry-sector-in-india-2017.pdf)

United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, 2016

The Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations Development Programme, n.d.) that especially align with India’s development priorities are: poverty and urbanization; nutrition and food security; education and employability; health, water, and sanitation; skilling, entrepreneurship, and job creation; climate change, clean energy, and disaster resilience; and gender equity and youth development.

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

See the section of this report titled “Cows, Buffaloes, Sheep, and Goats” for more information.

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

Since the time of writing, a report on this topic and co-authored by Deshpande of GFI has been published. See “A Survey of Consumer Perceptions of Plant-Based and Clean Meat in the USA, India, and China” (Bryant et al., 2019).

For more information about the public health, environmental, and animal welfare concerns regarding roadside slaughter, see Ghosh (2007).

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

Another stigma associated with animal advocacy work stems from its association with religious animal protectionism, an issue which is highlighted in the section of this report titled “Cow Protectionism.”

These ideas for career counseling were provided to us by Lakshmi Venkataraman (personal communication, April 16, 2019).

While there are differences in perceptions of consumption across castes within each religious group, Hindus are generally more opposed to the consumption of beef than Muslims.

For coverage of the controversy surrounding the renamings, see Ahmad (2018) and Shah (2018).

A. Sengupta & N.G. Jayasimha, personal communication, September 20, 2018

See Narayanan (2018) for more information about the issues with cow protectionism.

This issue is outlined in Venkataraman (2019).

We’d like to thank Lakshmi Venkataraman and Harshdeep Singh for their contributions to this list of questions.

United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, 2016

There have been avian flu outbreaks every year since 2011–2016. (United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service, 2016)

Filed Under: Research Tagged With: animal agriculture, animal welfare, bric, effective altruism, effective animal advocacy, farmed animals, India

About ACE Team

Amazing website and blog your

Thank you so much for providing such amazing information!

Thank you for this very informative report!

One statement that was difficult to believe is “ around 400 million rural people are employed in the livestock sector”. That is almost a third of the country and an even higher percentage of country’s workforce! And with 1,286 million animals, there would only be 3 animals per employed person which is unrealistic. I see that the claim comes from a respectable-looking source but it doesn’t explain in, and maybe the claim is a typo or something.

Also, I’d put the “Conclusions” section at the top and rename it to “Summary”. This would allow people to quickly get the gist of the report.

Hi Saulius,

Thank you for your thoughtful feedback!

I’ve looked into the data you’re referring to and I found that it was indeed an error in the cited source (the correct number is 20.5 million). I’ve updated the post to reflect this change—thank you for pointing it out!

Regarding your idea for renaming and moving the conclusion section, we plan to move this blog post to a static page on our website in the future, at which point we’ll take your surggestion into consideration.

Best,

Melissa