The Albert Schweitzer Foundation

Archived Review| Review Published: | December, 2019 |

| Current Version | November, 2021 |

Archived Version: December, 2019

What does Albert Schweitzer Foundation do?

Albert Schweitzer Foundation (ASF) works primarily in Germany, though they now have a branch in Poland as well. They work as a nonprofit (rather than making grants like a typical foundation). They conduct corporate outreach campaigns encouraging companies to (i) adopt cage-free policies, (ii) make broiler chicken and fish welfare commitments, and (iii) commit to providing additional and improved vegan options. ASF also engages in legal work; for instance, in the last year, they have funded a lawsuit against a state Minister of Agriculture and defended undercover investigators in a trespassing case in Germany. Additionally, their scientific division researches topics related to animal welfare and ways to make their work more effective.

What are their strengths?

ASF has demonstrated a strong focus on effectiveness, scientific research, and goal-setting. They consistently and strategically consider how they can have the greatest impact in their work and actively look for ways to improve their strategy. They recently expanded their corporate outreach campaigns internationally and have helped coordinate major E.U. broiler campaigns with the Open Wing Alliance (OWA). They have also been working with REWE Group, one of Germany’s largest retailers, on how to implement their international cage-free commitment in countries throughout Central and Eastern Europe by 2025. In addition, ASF launched their Aquaculture Welfare Initiative last year and at least eight retailers are already on board, including a foreign aid agency that wants to help aquaculture producers in developing countries meet welfare standards for German and European markets. We think that interventions targeting the welfare of farmed chickens and fishes may be particularly effective given the large number of animals being used and the neglectedness of advocacy on their behalf.

What are their weaknesses?

It seems that ASF often has many simultaneous ongoing projects and that they do not always have the capacity to implement their plans quickly. We think that leadership could think more strategically about deciding which projects to launch based on their capacity. For example, over the past year, they have been planning to expand to a third country but have been unable to do so thus far. ASF continues1 to lack racial diversity, but given the reported lack of racial diversity in the animal advocacy movement in Germany and Poland,2 it seems particularly challenging to make progress in this area. Additionally, while it may have some strategic advantages, our culture survey and discussions with staff indicated that ASF has a hierarchical and bureaucratic structure. We think it would benefit them to conduct their own regular culture surveys, especially given the changes they are working on this year.

Why did Albert Schweitzer Foundation receive our top recommendation?

ASF has a solid track record of corporate outreach in Germany, and we are optimistic that their strategy and skills will lead to meaningful progress in Poland and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe, an area with a younger and smaller animal advocacy movement. Additionally, ASF is one of the first animal charities beginning to prioritize corporate outreach on behalf of farmed fishes. We believe that farmed fish advocacy can be particularly impactful due to the large scale and neglectedness of farmed fish suffering.

How much money could they use?

We estimate that ASF’s plans for expansion will cost approximately $560,000 to $1.9 million, which we expect them to raise a portion of themselves. We expect that they would use additional funding to increase their staffing, expand to a new country, and hire external lawyers to conduct more lawsuits. We also expect that they would use additional funding to expand their corporate campaigns and their corporate outreach work related to fish welfare.

What do you get for your donation?

From an average $1,000 donation, ASF would spend about $617 on corporate outreach, $216 on legal advocacy, and $166 on corporate campaigns.

We don’t know exactly what ASF will do if they raise additional funds beyond what they’ve budgeted for this year, but we think additional marginal funds will be used similarly to existing funds.

Albert Schweitzer Foundation has been one of our Top Charities since November 2018. They were one of our Standout Charities from December 2014 to November 2018.

See ACE’s 2018 review of ASF (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2018).

Table of Contents

- How Albert Schweitzer Foundation Performs on our Criteria

- Interpreting our “Overall Assessments”

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Questions for Further Consideration

- Supplementary Materials

How Albert Schweitzer Foundation Performs on our Criteria

Interpreting our “Overall Assessments”

We provide an overall assessment of each charity’s performance on each criterion. These assessments are expressed as two series of circles. The number of teal circles represents our assessment of a charity’s performance on a given criterion relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated.

| A single circle indicates that a charity’s performance is weak on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated: | |

| Two circles indicate that a charity’s performance is average on a given criterion, relative to other charities we’ve evaluated: | |

| Three circles indicate that a charity’s performance is strong on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated: |

The number of gray circles indicates the strength of the evidence supporting each performance assessment and, correspondingly, our confidence in each assessment:

| Low confidence: Very limited evidence is available pertaining to the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to other charities. The evidence that is available may be low quality or difficult to verify. | |

| Moderate confidence: There is evidence supporting our conclusion, and at least some of it is high quality and/or verified with third-party sources. | |

| High confidence: There is substantial high-quality evidence supporting the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to other charities. There may be randomized controlled trials supporting the effectiveness of the charity’s programs and/or multiple third-party sources confirming the charity’s accomplishments.1 |

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Overall Assessment:

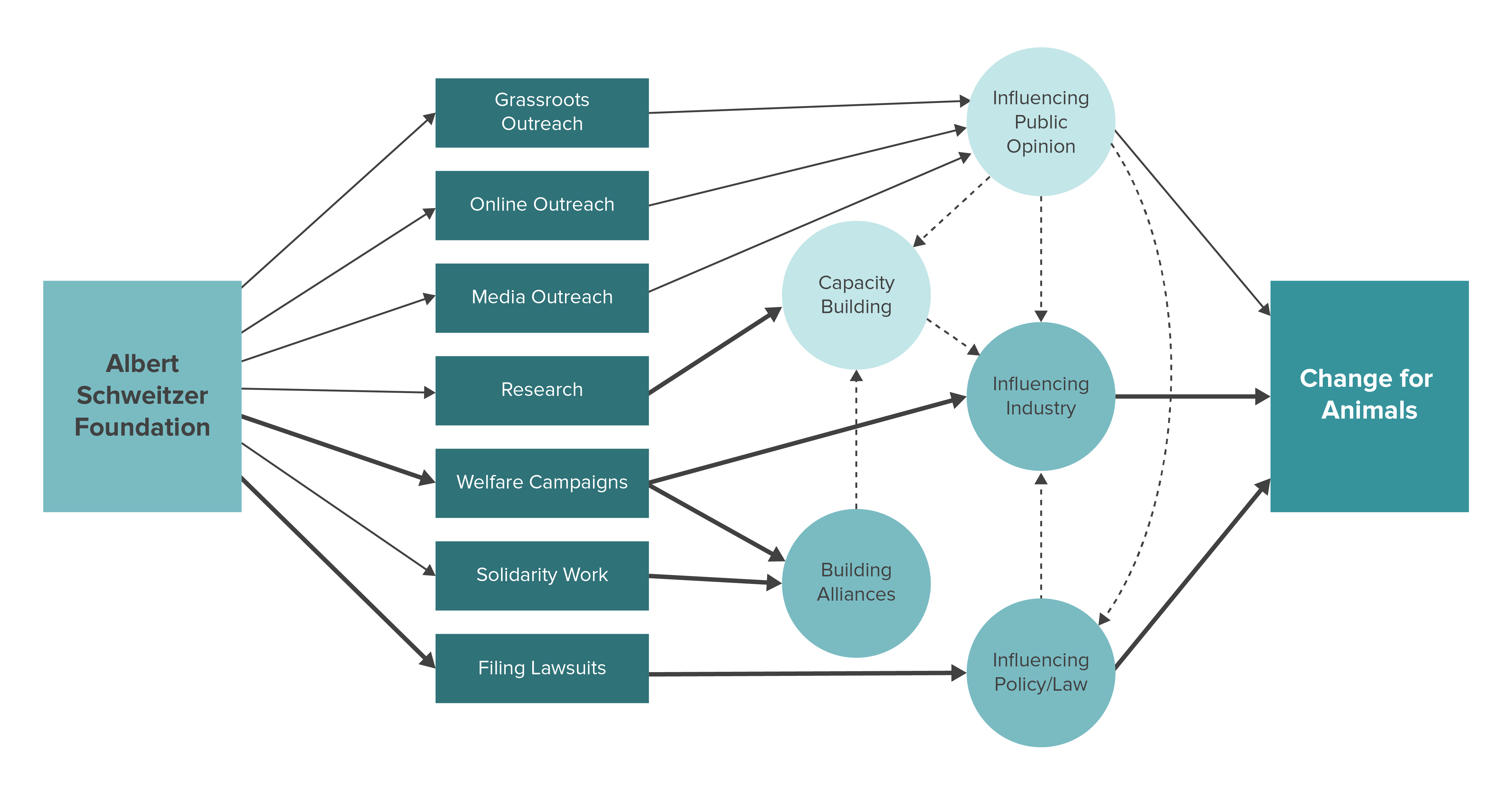

When we begin our evaluation process, we consider whether each charity is working in high-impact cause areas and employing effective interventions that are likely to produce positive outcomes for animals. These outcomes tend to fall under at least one of the categories described in our Menu of Outcomes for Animal Advocacy. These categories are: influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

Cause Areas

Albert Schweitzer Foundation focuses primarily on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we believe is a high-impact cause area.

Theory of Change

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

A note about long-term impact

We represent some of each charity’s long-term impact in our theory of change diagrams, though we are generally much less certain about the long-term impact of a charity or intervention than we are about more short-term impact. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew towards overemphasizing short-term impact. Nevertheless, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most. The potential number of individuals affected increases over time due to both human and animal population growth as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Interventions and Projected Outcomes

ASF pursues many different avenues for creating change for animals: They work to influence public opinion, build the capacity of the movement, influence industry, build alliances, and influence policy and the law. Below, we describe the work that they do in each area, listed roughly in order of the financial resources they devote to each area (from highest to lowest).

Influencing industry

ASF works with corporations to adopt better animal welfare policies and ban particularly cruel practices in the animal agriculture industry. In the short to medium term, corporate outreach can create change for a larger number of animals than individual outreach can with the same amount of resources. It also seems more tractable to secure systemic change one corporation at a time, rather than lobbying for larger-scale legislative change. Though the long-term effects of corporate outreach are yet to be seen, we believe that these interventions have a high potential to be impactful when implemented thoughtfully.

ASF currently prioritizes cage-free egg and broiler chicken welfare commitments. Cage-free egg systems are believed to reduce hen suffering by increasing the space available to hens and providing them important behavioral opportunities, although during the transition process mortality may increase, and there is some risk that it may remain elevated.2 ASF is also campaigning for companies to switch to higher welfare (but likely slower growing) breeds of broiler chickens and to commit to provisions on stocking density, lighting, and environmental enrichments. Such commitments may lead to higher welfare but also to more animal days lived in factory farms.

ASF recently launched their aquaculture program. We think that farmed fish advocacy is a particularly promising cause area due to the current neglectedness of the issue, the likelihood that farmed fish suffering is large in scale, and the potential tractability of interventions to improve farmed fish welfare. ASF’s aquaculture program seeks buy-in from retailers to improve farmed fish welfare. Additionally, ASF prioritizes technological developments such as the development of improved systems for stunning, transport, and handling, as well as the use of AI to monitor indicators of farmed fish welfare and to solve welfare problems.

ASF’s strategy is to try to foster positive and cooperative relationships with companies and to hold off on negative pressure until their more constructive efforts have proven fruitless. Aside from working directly with companies to secure welfare commitments, ASF also engages in the following activities: (i) organizing industry workshops on animal welfare topics, (ii) publishing industry rankings based on vegan offerings, and (iii) publishing a website and a newsletter with information and resources to help move the food industry away from using animals and towards a more plant-based focus.

Building alliances

ASF’s outreach to key influencers provides an avenue for high-impact work since it can involve convincing a few powerful people to make decisions that could influence the lives of millions of animals. We believe that the impact of building alliances varies considerably depending on who the key influencers are and the kinds of decisions they can make.

A core part of ASF’s strategy is to engage with key influencers, who they refer to as “multipliers.”3 ASF targets multipliers in politics, the media, science, agriculture, and the animal advocacy movement. They engage with key influencers through targeted networking activities and the maintenance of a press distribution list. They also visit specialist events, participate in working groups, give presentations, and commission studies. Since they take a collaborative approach to corporate welfare campaigns, we consider their corporate work to be alliance-building as well.

In Poland, ASF has worked on building alliances with other movements: For example, their country director wrote the position paper on animal rights for the Women’s Congress.4 Alliances such as these have the potential to help promote a more inclusive and diverse movement. Using social justice spaces to promote animal protection may have several benefits: Novel audiences could be reached, strategies could be shared, and efforts could be made to address multiple systems of oppression.

Influencing policy and the law

ASF works to encode animal welfare protections into the law. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects to be long-lasting. We believe that encoding protections for animals into the law is a key component of creating a society that is just and caring towards animals.

While it will be years before the cases are decided, ASF has begun the process of filing lawsuits on behalf of animals in Germany. They plan to pursue lawsuits to improve farmed animal welfare with the goal of receiving decisions from the highest courts.5 We think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to have an impact on a large number of animals, and they are more likely to be followed through on than similar corporate campaigns. ASF may be particularly well suited to pursue these cases because they have a board with strong legal expertise.6

Capacity building

Working to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement can have far-reaching impact. While capacity-building projects may not always help animals directly, they can help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Our recent research on the way that resources are allocated between different animal advocacy interventions suggests that capacity building is currently neglected relative to other outcomes such as influencing public opinion and industry. ASF engages in animal advocacy research, which is a form of capacity building.

ASF publishes scientifically informed articles about animals, vegan health, the environmental impacts of animal agriculture, and public demands to raise animal welfare.7 This work does not impact animals directly, but it may help educate the public by providing valuable resources to other organizations, animal advocates, and the media.

ASF also researches effective advocacy, which may play a pivotal role in how successful an organization can be. ASF does research relating to animal welfare and evaluates the effectiveness of their programs: For example, they plan to conduct research on the effectiveness of their Vegan Taste Week.8 ASF shares the results of their research publicly and/or with other advocacy organizations. Beyond providing information, ASF also helps advocates increase their impact by giving workshops on burnout prevention and working with groups to improve quality management in the movement.

Influencing public opinion

ASF works to influence individuals to adopt more animal-friendly attitudes and behaviors through media outreach, online outreach, and events such as Vegan Taste Weeks. The effects of public outreach are particularly difficult to measure for at least two important reasons. First, most studies of the effects of public outreach rely on self-reported data, which is generally unreliable.9 Second, even if we understood the effects of public outreach on individual behavior, we still know very little about how animals are impacted by behaviors such as individuals changing their diets, deciding to vote for animal-friendly laws, or becoming activists. Despite the uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of most public outreach interventions, we do think it’s important for the animal advocacy movement to target at least some outreach toward individuals. A shift in public attitudes and consumer preferences could help drive industry changes and lead to greater support for more animal-friendly policies; in fact, it might be a necessary precursor to more systemic change. On the whole, however, we believe that efforts to influence public opinion are much less neglected than other types of interventions, as we describe in our Allocation of Movement Resources report.

ASF has begun the process of deprioritizing their public outreach programs.10 However, they continue to run Vegan Taste Weeks and a nationwide campaign week intended to raise awareness of factory farming. While their campaigns department primarily focuses on corporate outreach, they do some consumer outreach in addition to their Vegan Taste Weeks.11

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

Overall Assessment:

We look to recommend charities that are not just high impact, but also have room to grow. Since a recommendation from us can lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding, we look for evidence that the charity will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. We consider whether there are any non-monetary barriers to the charity’s growth, such as time or talent shortages. To do this, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. We also consider the charity’s existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential areas for growth and expansion.

Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. We check in with each of our Top Charities mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented below to indicate whether we still expect them to effectively absorb additional funding at that point.

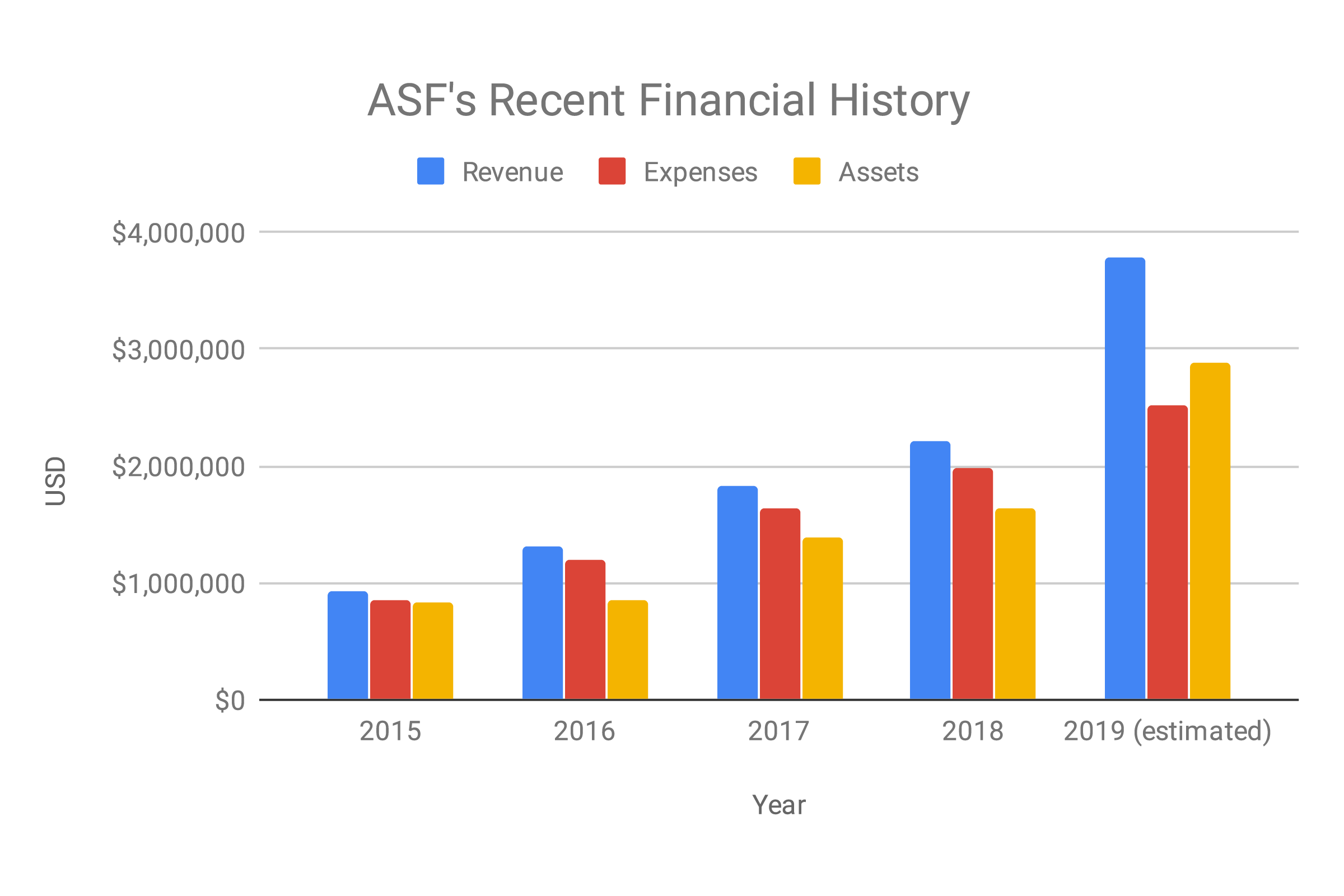

Recent Financial History

The following chart shows ASF’s recent revenue, assets,12 and expenses.13, 14 In this chart, the 2019 revenue and expenses are estimated based on the financials of the first six months of 2019.15 ASF notes that their fundraiser became the head of human resources at the beginning of 2019 and that in July, they hired a new fundraiser. This may have resulted in our estimates for 2019 revenue being underestimated.16

Estimated Future Expenses

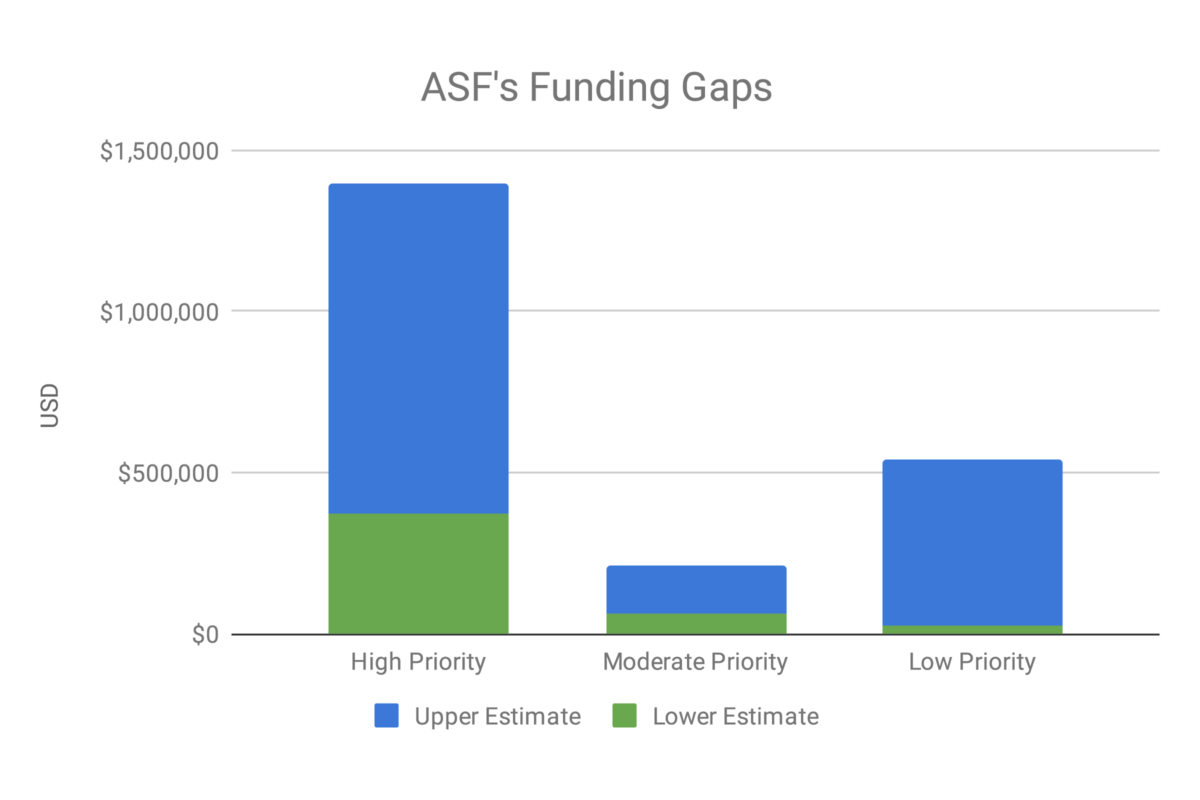

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area likely varies in its cost-effectiveness. In order to evaluate room for more funding over three priority levels, we consider each charity’s estimated future expenses,17 the estimated effectiveness18 of each future expense, and the feasibility of meeting each expense if more funding were provided.19

| Estimated future expense | Funding estimate | Priority level |

|---|---|---|

| Hiring 7.6 to 10 new staff members20 | $0.17M to $0.84M21 | High (76%) and moderate (24%) |

| Additional expenses for expanding to a new country22 | $21k to $0.12k | High (76%) and moderate (24%) |

| Hiring external lawyers for conducting more lawsuits23 | $54k to $0.80M | High |

| Expanding corporate outreach to reduce fish suffering24 | $48k to $73k | High (76%) and moderate (24%) |

| Expanding corporate campaigns25 | $26k to $39k | High (76%) and moderate (24%) |

| Possible additional expenditures | $31k to $0.59M26 | Low |

Estimated Room for More Funding

The cost of ASF’s plans for expansion over the three priority levels is estimated via Guesstimate and visualized in the chart above. ASF’s plans for expansion are expected to cost between $0.56M and $1.9M. Our room for more funding estimates include a linear projection of the charity’s revenue from previous years to predict the amount by which we expect the revenue to increase or decrease in the next year. ASF has received funding influenced by ACE as a result of its prior recommended charity status, so in order to more accurately estimate their room for more funding, we have subtracted the estimated ACE-influenced funding from our estimates of future revenue, which means the charity’s real 2020 revenue could be higher than the revenue we predict.27 Comparing ASF’s estimated revenue for 201928 and 2020,29 this projection predicts that in the next year, the revenue will change between -0.31M and 1.6M.30 As mentioned before, for this number we have not included ACE-influenced revenue so as to account for our own impact. The estimates for change in revenue are more uncertain than the estimated costs of expected expansion, so we put limited weight on them in our analysis and put more weight on our estimate for cost of expansion.

Criterion 3: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

Overall Assessment:

Information about a charity’s track record can help us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments, which is information that cannot always be incorporated into our other criteria. An organization’s track record is sometimes a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences between two charities.

In this section, we consider whether each charity’s programs have been well executed in the past by evaluating some of the key results that they have accomplished. Often, these outcomes are reported to us by the charities and we are not able to corroborate their reports.31 We do not expect charities to fabricate accomplishments, but we do think it’s important to be transparent about which outcomes are reported to us and which we have corroborated or identified independently. The following outcomes were reported to us unless indicated otherwise.

ASF was founded in 2000, but their most important programs in 2018–2019 (in terms of staff hours invested and expenses) are fairly recent. This is especially true for their Corporate Campaigns and Legal Work programs which started in 2018 and 2017, respectively. Below is our assessment of each of these programs, ordered according to the expenses invested in each one (from highest to lowest) from 2018 to mid-2019:

Programs

Program Duration

2008-present

Key Results32

- Achieved 17 cage-free and 7 broiler welfare commitments in Germany, Poland, and internationally33 (2018–2019)

- Launched the Aquaculture Welfare Initiative with at least 8 German retailers34 (2018–2019)

- Achieved a commitment to improve the welfare standards of hens reared under the Association for Controlled Alternative Animal Husbandry (KAT) (2019)35

- Worked with the University of Heidelberg to implement a vegan week in their student catering services36 (2018)

- Developed the European Chicken Commitment (ECC) with other organizations (2017)

Our Assessment

ASF has a strong track record of success in achieving cage-free commitments in Germany, where most large-scale companies have stopped using eggs from caged hens. ASF only recently expanded to Poland (2017), and they report most of their 2018–2019 cage-free victories in this country.37 They also recently launched their corporate work to improve broiler chicken welfare (2017), and they have already achieved at least 7 corporate commitments through the ECC.38 Since some of these victories have been achieved in collaboration with other organizations,39 it is difficult to determine the impact of ASF’s Corporate Outreach program. However, the commitments achieved by ASF’s corporate work will likely affect a large number of chickens per year.40

ASF also started their corporate work on fish welfare in 2017, launching their official campaign two years later (2019) with the participation of at least eight retailers. Although we are uncertain about the implementation rate of these commitments, they have the potential to affect a large number of farmed fishes.

ASF’s corporate outreach work has also included the promotion of vegan options. Since 2014, ASF has been working on their Vegan Taste Week campaign aimed at promoting plant-based diets through online individual outreach.41 It seems that in 2018, they added a corporate outreach component to this campaign, successfully implementing a vegan week on a university campus. Although we are uncertain about the magnitude of their impact, these activities are likely to increase demand for plant-based products, ultimately leading to a decline in the number of animals raised for food.

Program Duration

2017-present

Key Results42

- Funded a lawsuit against the Minister of Agriculture of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, who has since resigned43 (2018)

- Defended investigators in a case of trespassing in Germany44 (2018)

Our Assessment

This program started in 2017 with a lawsuit aimed at reducing the suffering of farmed turkeys—a lawsuit that is still ongoing. In 2018, ASF supported a lawsuit against a Minister of Agriculture which was successful in pressuring the minister to resign,45 probably leading to an improvement in the welfare standards of farmed pigs in the short term.

In 2018, they also had a legal success when defending investigators in a case that will likely have a major indirect impact on animals by legalizing investigations of animal agriculture facilities in Germany. In 2019, ASF filed a constitutional appeal to overturn a court ruling against an undercover investigator for unlawful entry into a factory farm in German. The case is still ongoing. If successful, it could impact farmed animals on a national scale.46

Program Duration

2018-present

Key Results47

- Won 3 broiler welfare campaigns (Dr. Oetker,48 Ikea, and Sodexo)49 and a cage-free campaign against Marriott50 in collaboration with other organizations (2018–2019)

- Supported the OWA‘s successful cage-free campaigns against Hilton and Best Western51 (2019)

Our Assessment

ASF’s corporate campaigns–in collaboration with other organizations—have resulted in several victories since the launch of the program. Following petitions and protests against specific companies, at least three multinational companies have made commitments to raise broiler chicken welfare standards, and another has committed to using cage-free eggs.

Since these campaigns were carried out in collaboration with other organizations as part of the OWA and the ECC, it is difficult to determine the impact of ASF’s Corporate Campaigns program. However, if the commitments that are achieved are implemented, they will likely affect a large number of animals per year.

Criterion 4: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

Overall Assessment:

A charity’s recent cost-effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component to understanding how cost-effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources and compare that to the outcomes they have achieved in each of their main programs.

This year, we have used an approach in which we more qualitatively analyze a charity’s costs and outcomes. In particular, we have focused on the cost-effectiveness of the charity’s specific implementation of each of its programs in comparison to similar programs conducted by other charities we are reviewing this year. We have categorized the charity’s programs into different intervention types and compared the charity’s outcomes and expenditures from January 2018 to June 2019 to other charities we have reviewed in our 2019 evaluations. To facilitate comparisons, we have also compiled spreadsheets of all reviewed charities’ expenditures and outcomes by intervention type.52

Analyzing cost-effectiveness carries some risks by incentivizing behaviors that, on the whole, we do not think are valuable for the movement.53 Particular to the following analysis, we are somewhat concerned about our inclusion of staff time and volunteer time. Focusing on staff time as an indicator of cost-effectiveness can reward charities that underpay their staff, and discourage organizations from working towards increasing salaries to be more in line with the for-profit sector. As for volunteer time, we think that volunteer programs can increase the cost-effectiveness of a charity’s work, however, overreliance on volunteers can make a charity’s work less sustainable. While we think that these factors are relevant and worth including in our analysis of cost-effectiveness, we encourage readers to bear these concerns in mind while reading this criterion.

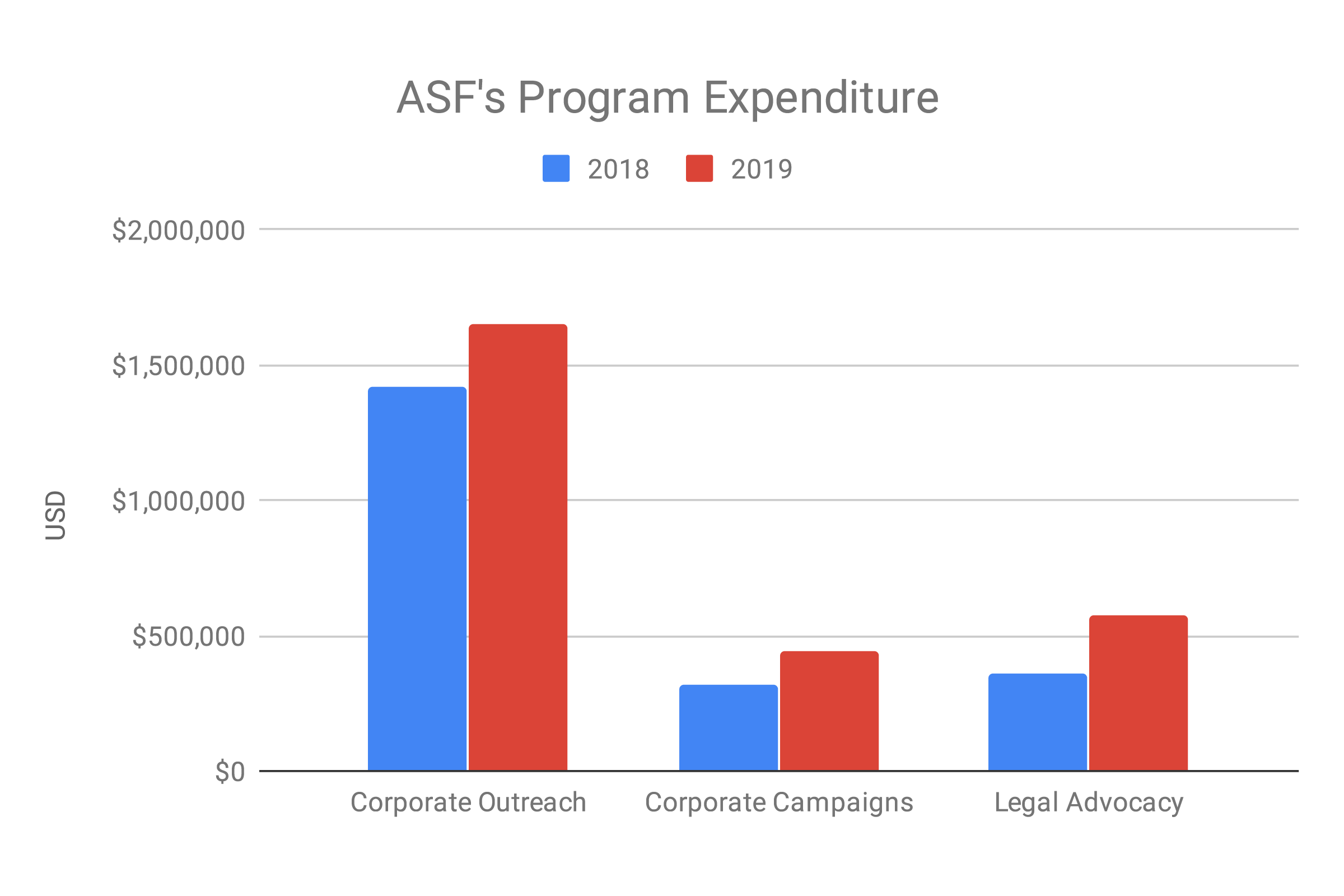

Overview of Expenditures

The following chart shows ASF’s total expenditures in 2018 and 2019, divided by program.54

We asked ASF to provide us with their expenditures for their top 3–5 programs55 as well as their total expenditures. The estimates provided in the graph were calculated by dividing up their total expenditures proportionately to the size of their programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost-effectiveness.

Corporate Outreach

Summary of outcomes: secured 17 cage-free egg commitments, mostly in Poland, and seven broiler chicken welfare commitments; launched the Aquaculture Welfare Initiative and secured membership from eight German retailers; secured one fur-free commitment and one institutional commitment; and organized an industry workshop on dairy cow welfare. For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in corporate outreach.

Note: ASF engages in two programs that we have categorized as corporate outreach—Corporate Outreach and Corporate Campaigns. In the former, they focus on working collaboratively with companies to help them make commitments to improve welfare, whereas in the latter they take a more adversarial role, targeting companies with public awareness campaigns to pressure them into making commitments. As the resource usage and outcomes of each program are distinct, we have kept them as separate categories in the following analysis.

Use of resources

Table 1: Estimated resource usage in ASF’s corporate campaigns, Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Resources | ASF’s Corporate Campaigns | ASF’s Corporate Outreach | Average across all reviewed charities56 |

| Expenditures57 (USD) | $540,000 | $2,200,000 | $1,200,000 |

| Staff time (weeks58) | 167 | 398 | 380 |

| Volunteer time (weeks59) | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Relative to their expenditures for this program, ASF’s staff time is much lower than the average of charities we reviewed this year.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

Table 2: Estimated number of animals affected by corporate commitments, Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Number affected per year by commitments (Corporate Campaigns)60 | Number affected per year by commitments (Corporate Outreach)61 | Average across all reviewed charities62, 63 | |

| Caged hens | 0.1M–0.8M | 0.9M–9.1M | 4M–10M |

| Broiler chickens | 3.8M–14M | 7.3M–42M | 22M–35M |

Corporate outreach that is focused on securing commitments to improve welfare has a direct impact on animals. After factoring in the proportional responsibility that ASF had for each commitment, we can estimate how many animals will be affected when the commitments are implemented.64 Overall, after accounting for expenditures, their work appears to be less cost effective than the average of the charities we have reviewed this year. This estimate has limitations in that the ranges are often very uncertain, and it does not account for other activities that charities engage in as part of their corporate outreach programs.

Additionally, compared to other organizations, ASF appears to have a unique advantage in Germany as it seems that companies have preferred to implement their cage-free commitments very quickly, often prior to announcing them. This is a distinct advantage over the U.S., for example, where companies have made commitments often with deadlines 5–10 years after the commitment, which leaves the risk that they will not be followed through on without continued campaigning.65

ASF was also one of the first charities to incorporate fish into their Corporate Outreach program with the establishment of their Aquaculture Welfare Initiative, and they have since secured commitments from eight retailers in Germany to improve welfare standards. As fishes are currently the most neglected and largest of the farmed animal groups, it may be that their work in this area is particularly cost effective in comparison to corporate campaigns targeting other animal groups.66

After accounting for all of their outcomes and expenditures, ASF’s corporate outreach seems close to the average cost-effectiveness of other reviewed charities in 2019.

Legal Advocacy

Summary of outcomes: defended investigators accused of trespassing; funded a lawsuit against the Minister of Agriculture in North Rhine-Westphalia, who has since resigned; and filed a constitutional appeal in opposition to a court ruling against animal welfare laws (outcome pending). For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in legal advocacy.

Use of resources

Table 3: Estimated resource usage in ASF’s legal advocacy, Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Resources | ASF | Average across all reviewed charities67 |

| Expenditures68 (USD) | $560,000 | $500,000 |

| Staff time (weeks69) | 6 | 187 |

| Volunteer time (weeks70) | 10 | 12 |

Following a similar trend to their corporate outreach programs, ASF’s expenditures greatly outweigh their staff time in their legal advocacy program. This is because their legal work is primarily carried out by external lawyers, not staff members.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

ASF’s legal advocacy has outcomes for animals that are indirect, and as such, it is difficult to make an assessment of their cost-effectiveness. It is likely that the most impactful outcome they have achieved is the successful defense of investigators accused of trespassing. Successes in cases like this are likely to be important even if they don’t directly impact animal suffering; they may set a national precedent for possible future cases against investigators and thus have a long-term impact.

ASF’s approach of targeting a specific minister will likely have an impact in the short term, assuming that their replacement is more supportive of animal causes. However, this impact is localized to a particular state and doesn’t change the legal system in any way, thus it seems comparatively less cost effective than their other legal advocacy work. After accounting for all of their outcomes and expenditures, ASF’s legal advocacy seems slightly less cost effective than the average of other charities reviewed in 2019.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

Overall Assessment:

By conducting reliable self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs and modify or discontinue less successful programs. When such systems of improvement work well, all stakeholders benefit: Leadership is able to refine their strategy, staff better understand the purpose of their work, and donors can be more confident in the impact of their donations.

In this section, we consider how the charity has assessed its programs in the past. We then examine the extent to which the charity has updated their programs in light of past assessments.

How does the charity identify areas of success and failure?

ASF regularly examines their work to see whether they are on track and whether they need to make changes; after each campaign or project, they do an informal post-mortem analysis.71 Although they do not use a formal self-evaluation tool, they are building a database with their “lessons learned” so that every time someone starts a project, they can see mistakes made and lessons learned from previous, similar projects.72

ASF reports that they measure the outcomes of their programs by setting goals and using a seven-step impact program that starts with the outputs—the work that is done—and goes through outcomes, followed by impact.73 To evaluate the impact of their corporate outreach work, they developed a ranking of companies using a priority point system that considers the size of the company, the number of animals they use, and the influence they have on the market. Within this framework, the senior management team does monthly check-ins on their progress and discusses whether they need to take any action. Then, they consult with the rest of the team about where they are in terms of their goals and progress.

ASF has consulted with external advisors to redesign their salary structure and to improve their organizational culture and internal policies.74

Does the charity respond appropriately to identified areas of success and failure?

We believe that ASF has responded appropriately to their self-determined areas of success and failure in many ways. We list three salient examples below.

- ASF reports that they started their broiler welfare corporate outreach work by approaching companies in a way that was similar to the way they approached companies for their successful cage-free campaigns. After several months of very slow progress in obtaining broiler welfare commitments, they decided to change their tactics and they began launching pressure campaigns. According to ASF, this change in tactics resulted in key corporate victories (e.g. Sodexo75 and IKEA76). Although they recognize that they would have liked to make this decision sooner, they still made a significant change in their tactics to increase their impact, suggesting that they are capable of accepting their own mistakes and making changes to less successful programs.77

- Partly based on their strong track record of success in obtaining cage-free commitments in Germany, ASF has directed more efforts to their corporate outreach work. They decided to change their street campaigns team—which was focused exclusively on consumer outreach—and transform the team into a campaigns department focused mostly on corporate outreach while also increasing the size of the team. ASF reports that they realized that online ads were more successful at generating leads for their Vegan Taste week than their offline consumer outreach (achieving more open and click rates than offline leads), so they decided to cut that part of the program.78 With this recent change, two out of ASF’s three key programs are focused on corporate outreach, which has probably increased their capacity to obtain corporate commitments.

- ASF reported that last year, they decided to expand to a third country but that they have not yet implemented their plans because they do not have the capacity to successfully establish in another country.79 Since then, they have focused on making a series of structural changes to optimize organizational effectiveness, including changing employees’ roles and responsibilities (one person fully dedicated to human resources, their Corporate Outreach Director only focused on international work, another team member only focused on German corporate outreach); hiring a country director for Poland;80 and consulting with external advisors to improve organizational culture, update salary structure, and develop internal policies.81 While we recognize the difficulty they have faced in implementing this expansion, we believe it is worth investing resources to improve current management practices and to be prepared as an organization before expanding to an additional country without capacity.

We believe that ASF failed to respond appropriately to their self-determined areas of success and failure in at least the following way:

In our previous review of ASF, a lack of diversity in their team was identified—particularly gender and racial diversity—as well as the need to make their office in Germany more accessible to people with disabilities. While ASF has increased gender diversity among their staff,82 it seems that they have not incorporated measures to adapt their office for people with disabilities yet, as mentioned by many staff members in the culture survey that we distributed this year.83, 84 ASF’s racial diversity has not increased either, but given the alleged lack of racial diversity in the animal advocacy movement in Germany and Poland,85 it seems particularly challenging to make progress in this area. In addition, several respondents mentioned that the organization’s top leadership is still heavily white and male, suggesting a need to more actively promote diversity and inclusion within the organization.

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

Overall Assessment:

Strongly-led charities are likely to be more successful at responding to internal and external challenges and at reaching their goals. In this section, we describe each charity’s key leadership and assess some of their strengths and weaknesses.

Part of a leader’s job is to develop and guide the strategic vision of the organization. Given our commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we look for charities whose strategy is aligned with that goal. We also believe that a well-developed strategic vision should include feasible goals. Since a well-developed strategic vision is likely the result of well-run strategic planning, we consider each charity’s planning process in this section.

Key Leadership

Leadership staff

Mahi Klosterhalfen is the CEO and President of ASF, and has served the organization for 11 years. He also serves on Compassion in World Farming‘s board of trustees, showing a willingness to collaborate with other organizations. Other key leaders at ASF include Silja Kallsen-MacKenzie (International Director of Corporate Outreach), Carsten Halmanseder (Campaigns Director), Konstantinos Tsilimekis (COO), and Karolina Skowron (Country Director in Poland).

According to a culture survey86, 87 that we distributed to ASF’s team, respondents generally agreed strongly that ASF’s leadership is attentive to the organization’s strategy. They also strongly agreed that their leadership promotes external transparency and they agreed (though slightly less strongly) that they promote internal transparency.

Board of Directors

ASF’s Board of Directors consists of three members, including CEO Mahi Klosterhalfen. In the U.S., it’s considered a best practice for nonprofit boards to be comprised of at least five people who have little overlap with an organization’s staff or other related parties. However, there is only weak evidence that following this best practice is correlated with success.

Given the board’s small size, they represent a limited amount of diverse viewpoints. We consider the board’s relative lack of diversity to be a weakness. We believe that boards whose members represent occupational and viewpoint diversity are likely most useful to a charity, since they can offer a wide range of perspectives and skills. There is some evidence suggesting that nonprofit board diversity is positively associated with better fundraising and social performance,88 better internal and external governance practices,89 and the use of inclusive governance practices that allow the board to incorporate community perspectives into their strategic decision making.90

Strategic Vision and Planning

Strategic vision

ASF’s mission statement is to address “the greatest source of pain and death for animals” (industrial agriculture). We support ASF’s choice to focus on improving farmed animal welfare and promoting plant-based diets because we consider farmed animal protection to be the most promising area for doing the most good for animals, other things being equal. ASF’s framework for making progress in these areas also makes sense to us. Their “pillars of change” framework is quite similar to our own independently-developed menu of outcomes.

Strategic planning process

Each year, ASF’s management team has a series of meetings in which they review their work from the previous year and discuss which projects they will continue or initiate the following year.91 During this process, the organization relies on their three-year strategy as a guide.92

ASF’s board plays an instrumental role in setting the organization’s three-year strategy. They do so with a focus on four “pillars” of change: companies, consumers, multipliers, and the law. They currently see working to influence companies and the law as more neglected than working to influence consumers and multipliers, and thus they view it as a more promising approach in the short and medium term.

Goal setting and monitoring

Our impression is that ASF sets yearly goals that are both achievable and aligned with their long-term strategy. In 2018, they shared a flow chart system with us, which they use to ensure that they launch projects only when (i) they have the staff capacity to complete the project, (ii) staff capacity is not needed to complete ongoing projects, and (iii) staff capacity could not be expended on a higher-priority project.

ASF uses a seven-step process called “the results staircase” to monitor progress on their outcomes and impact.93 Their sharp, consistent focus on project prioritization and monitoring means that when they can’t achieve a longer-term goal right away, they have a clear sense of which steps to take and when.

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Overall Assessment:

The most effective charities have healthy cultures and sustainable structures to enable their core work. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about the culture they try to foster and their perceptions of staff morale. We review each charity’s policies related to human resources and check for essential items. We also send each charity a culture survey and request that they distribute it among their team on our behalf.

Human Resources Policies

Here we present a list of policies that we find to be beneficial for fostering healthy cultures. A green mark indicates that ASF has such a policy and a red mark indicates that they do not. A yellow mark indicates that the organization has a partial policy, an informal or unwritten policy, or a policy that is not fully or consistently implemented. We do not expect a given charity to have all of the following policies, but we believe that, generally, having more of them is better than having fewer.

| A workplace code of ethics that is clearly written and consistently applied throughout the organization | |

| Paid time off ASF offers 24 days of paid time off per year. |

|

| Sick days and personal leave ASF offers unlimited paid sick days, in accordance with German law. |

|

| Full healthcare coverage ASF Germany offers its employees vitamin D and B12 checkups in addition to their national healthcare program. ASF Poland offers its employees some upgrades to the Polish healthcare system. |

|

| Regular performance evaluations | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| A formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries |

| A written statement that they do not discriminate on the basis of race, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A written statement supporting gender equity and/or discouraging sexual harassment | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| An optional anonymous reporting system | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment or discrimination through all levels of the managerial chain up to and including the Board of Directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| A practice in place of documenting all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular, mandatory trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) | |

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for submitting reasonable accommodation requests | |

| Remote work option |

| Audited financial documents (including the most recently filed IRS form 990, for U.S. organizations) made available on the charity’s website | |

| Board meeting notes made publicly available | |

| Board members’ identities made publicly available | |

| Key staff members’ identities made publicly available |

| Formal orientation provided to all new employees | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Funding provided for books or other educational materials related to each employee’s work | |

| Paid trainings available on topics such as: diversity, equal employment opportunity, leadership, and conflict resolution | |

| Paid trainings in intercultural competence (for multinational organizations only) | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support |

In addition to the policies marked in green above, ASF has the following policies which seem beneficial, though we have not researched them extensively:

| ASF supports staff financially who make use of a German governmental retirement savings program. | |

| “€100 rule” All staff can make purchases of up to €100 (about $110) without questions asked in order to solve minor problems (e.g., replacing an old keyboard). |

Culture and Morale

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly towards all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. ASF worked with an external firm in 2019 in preparation to improve their culture and compensation scheme. According to ASF’s leadership, their culture is strong in the sense that it is mission-driven and pragmatic. One area for improvement is their level of bureaucracy; some staff describe ASF’s culture as too hierarchical, and some are hesitant to voice their opinions.94 This finding is consistent with the results of our culture survey from last year, as described in our 2018 review of ASF. On our 2019 culture survey of ASF, none of the respondents mentioned ASF’s hierarchy, though several mentioned that ASF has been working to improve their culture following their workshops earlier this year.

According to the staff survey we distributed, ASF has a high level of employee engagement. Nine German employees and five Polish employees described ASFs internal communication style as “friendly,” “warm,” “harmonious,” or similar. In the German office, the second most common description of ASF’s communication style was “factual,” “accurate,” or similar. In the Polish office, many employees described ASF’s communication as “unclear,” “complicated,” or similar. It may be that communication within ASF’s Polish office is less clear than communication within ASF’s German office, or it may be that ASF’s leadership does a better job communicating clearly with their German office than their Polish one. Either way, ASF may want to take some steps to improve clarity in their Polish office.

ASF does not currently have a system for conducting regular culture surveys.95 We think that regular culture surveys are a good idea for any charity, and they may be particularly important for ASF following the changes they are working on this year.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion96

One important part of acting responsibly towards stakeholders is providing a diverse,97 equitable, and inclusive work environment. Charities with a healthy attitude towards diversity, equity, and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, which improves their ability to respond to new situations and challenges.98 Among other things, inclusive work environments should also provide necessary resources for employees with disabilities, require regular trainings on topics such as diversity, and protect all employees from harassment and discrimination.

ASF’s leadership acknowledges that their organization lacks racial diversity, which they attribute to the lack of racial diversity in the animal advocacy movement in Germany and Poland.99 They tell us that diversity of gender, age, and experience are still important to them and that they’ve improved on these metrics over time.

According to our culture survey, ASF’s employees agree that ASF has gender and experiential diversity, but not racial diversity. Some staff mentioned that ASF is inclusive of people with diverse sexual orientations, though others mentioned being uncertain of this. Like last year, a substantial portion of respondents mentioned the need for ASF Germany to be more accessible to employees with disabilities. Several ASF Germany respondents also mentioned that the organization’s top leadership is still heavily white and male, and may not be fully invested in improving the organization’s diversity, equity, and inclusion. Some respondents recommended that their leadership make more active efforts to improve diversity at ASF through their recruitment process.

ASF recently updated their policies on harassment and discrimination, and they conducted a day-long workshop for the entire team.100 Respondents to our culture survey agreed very strongly that ASF works to protect staff, interns, and volunteers from harassment and discrimination in the workplace. We learned of one incident of verbal harassment that occurred in the past year at ASF and everyone who reported it to us believed that it was handled responsibly by the organization’s leadership.

Sustainability

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in leadership. The charity should not seem likely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, it should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

ASF has traditionally received most of their support from small monthly donations of ten to 12 euros, on average. Recently, they have begun to receive some larger donations—including a $1 million grant for two years of general support from the Open Philanthropy Project in 2017. ASF is aware of the risk of becoming too dependent on a small number of large donations; they have worked to solicit a large number of small donations as the primary source of their funding.101

In our view, ASF has very strong leadership; Klosterhalfen takes a very large share of the responsibility for the organization’s success, and he may be difficult to replace if the occasion should ever arise. However, ASF is a fairly large organization with a talented and committed staff, and they have well-documented policies and training materials. Their strategy documents would provide guidance through any leadership transitions; these documents are clear and are set for three years at a time. As such, we think that ASF would likely survive a potential change in leadership.

Questions for Further Consideration

Does ASF have a plan to ensure the implementation of corporate commitments achieved in Poland?

ASF’s response:

“We decided to either make this one of our own priorities (asking for annual updates and applying pressure, if companies show a lack of effort) and/or to let CIWF (Compassion International) focus on this via EggTrack. It looks like CIWF will be actively monitoring progress in Poland through EggTrack. If the transparency that EggTrack creates won’t be enough to ensure the transition to cage-free eggs, we’ll help by applying additional pressure through campaigns.”

Has ASF considered focusing their Corporate Outreach program on achieving institutional commitments to reduce animal products rather than raise animal welfare standards?

ASF’s response:

“Yes, we’re planning to do so once we’ve made more progress on the ECC. For a while, we considered doing both (reduction work and broiler work) at the same time, but we realized that we need to focus our efforts on the ECC for now, in order to make real progress there. We also view our ECC work as an unusual form of meat reduction work as higher prices will lead to lower volumes bring competitive advantages to producers of plant-based alternatives.”

In comparison to other charities we reviewed this year, ASF’s legal program staff time seems to be particularly low relative to expenditures. Why does ASF think this might be the case?

ASF’s response:

“We don’t have any staff working full-time on legal issues. Instead, we hire lawyers on a case-by-case basis. These costs are then allocated to our project costs and not to our staff costs.”

How is ASF prioritizing their legal advocacy activities?

ASF’s response:

“We’re mostly looking at filing lawsuits that have high chances of a) impacting large numbers of animals and b) banning some of the worst practices in factory farming. You’ll see more of these in the future. We may divert from this form of prioritization in cases of less immediate but strategic value: e.g. it can be helpful to clarify legal questions where they’re most obvious. That’s why we filed a lawsuit for turkeys before filing one for broiler chickens: Getting a favorable ruling on overbreeding (which is illegal but practiced in Germany) should be easier in the case of turkeys who grow much older than broiler chickens and show more signs of overbreeding.”

Note that we are never 100% confident in the effectiveness of a particular charity or intervention, so three gray circles do not necessarily imply that we are as confident as we could possibly be.

For more information on the reliability of self-reported data, see van de Mortel (2008) in the Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. Also see Peacock (2018) on the use of self-reported dietary data.

We found that charities interpreted the question of how many assets they had very differently. Some interpreted assets as financial reserves, some as net assets, and some as material assets. We have interpreted assets as financial reserves, which we calculated by taking the assets from the previous year, adding the (estimated) revenue for the current year, and subtracting the (estimated) expenses for the current year.

Data for 2011–2017 draws from Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2017). Data for 2018 and the first six months of 2019 draws from Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2019).

We have included all financial information available from 2014 until mid-2019.

We assume that charities receive 40% of their revenue in the last two months of the calendar year. To calculate estimates of total revenue, we multiply the revenue from the first six months by 2.778. We assume that expenses stay constant over the year, so to calculate estimates of total expenses in 2019, we multiply expenses from the first six months by two.

The estimates are partly based on charities’ own estimates of planned expansion as expressed in our follow-up questions for them (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019).

See our cost-effectiveness estimates spreadsheet for more information.

Potential bottlenecks besides lack of funding include lack of operational capacity to support new staff members and difficulty to find and hire value-aligned individuals with the right skill sets. We base our estimates for capacity for expanding staff based on the current number of staff employed, as reported in Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2019). ASF currently employs 30 full-time staff—25 in Germany and 5 in Poland—and 4 part-time staff, all of whom are in Germany (Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2019). Our subjective assessment is that we are highly confident that ASF can hire 76% of the new staff they would like to hire before running into non-funding related bottlenecks. For 24% of the hires, we believe the non-funding related bottlenecks play a more significant role and we are only moderately confident that ASF can overcome these bottlenecks within the next year. Therefore, we estimate that 76% of new hires are high priority and 24% are moderate priority.

ASF notes that if they had enough funding, they would hire for the following positions in Germany: one additional fundraiser, one additional person for corporate outreach, one additional communications person, probably one person for lobbying/legislative work, and possibly one additional IT role. They note that in Poland, they would probably not grow the time for now, and in the next country, which is yet to be determined, they would hire for about 5 positions, mostly for corporate outreach, corporate campaigns, some administrative and some communications (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019). We believe that all of these positions are high impact as they are either directly working on an effective campaign or supporting an effective campaign.

We estimate salaries to be between $31k to $46k per year, based on ASF’s 2017 report on effectiveness with an uncertainty of +/- 20%. To estimate the total expenses related to hiring a new staff member, we multiply the salary with a distribution of 1.5 to 2.5 to account for recruiting expenses, employment taxes, benefits, training, equipment, etc. To account for the fact that people will be hired throughout the year and not only at the beginning, we multiply the expenses by a distribution of 0.25 to 1.25.

We estimate that around 20% of costs associated with expanding to a new country are related to non-staff expenses. We estimate that 76% of these costs are high priority, and 24% are moderate priority.

ASF is currently planning to launch lawsuits for broiler chickens and pigs. They note that “pigs will require at least three lawsuits for each stage of the system: sows & piglets, early fattening, fattening” (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019).

ASF notes that the non-staff costs of the corporate campaigns are mostly for paying consultants and project managers, mainly for fish work. ASF also notes they are currently spending less on fish work than they would like to (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019). From the spreadsheet outlining their top 3–5 programs (Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2019), we find that the projected program expenses for corporate outreach for 2019 is equal to 2*€272,112 = $598,225. 26% of the corporate campaigns expenses is for non-staff costs. If we assume that 10% of non-staff costs is related to fish campaigns and that they could double their non-staff budget, they would be able to spend $59,822 ± 20% on this in 2020.

Based on the spreadsheet describing ASF’s top 3–5 programs (Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2019), we estimate the total expenses for corporate campaigns in 2019 will be $80,604. ASF reported that the non-staff costs of their corporate campaigns are 20%, and that they could use more funding for their corporate campaigns as they are about to enter a “make or break” stage (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019). We estimate they will be able to effectively use a doubling of their budget ± 20%.

We use a range estimate of 1%–20% of ASF’s projected 2020 expenses to account for possible additional expenditures.

To estimate the revenue not influenced by ACE, we consider the total revenue per year and subtract the amount we estimate is influenced by ACE in the same year. We use these numbers to estimate the average growth not influenced by ACE. To calculate the estimated 2020 revenue, we add the average growth not influenced by ACE to the 2019 revenue not influenced by ACE. In the case of ASF, the amount of revenue influenced by ACE was $164,013 between the beginning of 2016 and mid-2019. For details, see our giving metrics reports from 2016, 2017, and 2018. At the time of writing, our 2019 Giving Metrics Report is not yet published.

The total revenue is based on the first six months of 2019 with an uncertainty of ± 10%.

The calculations on which this estimate is based exclude revenue influenced by ACE, and have an uncertainty of ± 20%. The calculations are made via a linear projection of the total revenue of previous years.

Adding the expected change in revenue to the cost of expansion, the total room for more funding would be between -$0.63M and $1.7M.

While we are able to corroborate some types of claims (e.g., those about public events that appear in the news), others are harder to corroborate. For instance, it is often difficult for us to verify whether a charity worked behind the scenes to obtain a corporate commitment, or the extent to which that charity was responsible for obtaining the commitment.

Since we did not ask charities to provide details about accomplishments prior to 2018, key results before this year were sourced from publicly available information and may be incomplete.

ASF reports 4 international cage-free commitments; from Transgourmet, Deutsche Hospitality, Kempinski, and ISS (Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2019).

ASF reports this commitment would affect 81 million hens (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019).

ASF reports that 11 of 17 cage-free commitments achieved since 2018 were in Poland (Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2019).

ASF reports collaboration with organizations such as Compassion In World Farming and The Humane League (Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2019).

According to one rough estimate, 10–280 chickens may be affected per every dollar spent on cage-free and broiler welfare corporate campaigns (Šimčikas, 2019).

Since we did not ask charities to provide details about accomplishments prior to 2018, key results before this year were sourced from publicly available information and may be incomplete.

Since we did not ask charities to provide details about accomplishments prior to 2018, key results before this year were sourced from publicly available information and may be incomplete.

Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2019; Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2019

Note that some charities’ programs do not fit in well with the rest of the reviewed charities according to our categorization of intervention type.

For a longer discussion of the limitations of modeling cost-effectiveness, see Šimčikas (2019).

To estimate their 2019 expenditures, we doubled the financial data they provided for Jan–Jun 2019.

This includes all charities reviewed in 2019 that are engaged in a program related to corporate outreach.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost-effectiveness. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work. We think it is unlikely that, in practice, volunteers are working full-time weeks, however we are using this unit in order to maintain a comparison with the amount of staff time used.

We provide these estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. For more information, see this explainer page.

We provide these estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. For more information, see this explainer page.

This only includes charities engaged in securing commitment for the type of animal in question.

We provide these estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. For more information, see this explainer page.

These estimates are informed by a variety of sources—charities’ self-reported estimates, information about the size and production output of the companies, data from the Open Philanthropy Project, etc. For more details, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in corporate outreach, and the accompanying Guesstimate sheet.

For more information, see Rethink Priorities (2019) and Open Philanthropy Project Farm Animal Welfare Newsletter (2019).

Since ASF was the only group securing corporate commitments of this kind for fishes, we decided not to include estimates in the comparative table.

This includes all charities reviewed in 2019 that are engaged in a program related to legal advocacy.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost-effectiveness. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work. We think it is unlikely that, in practice, volunteers are working full-time weeks, however we are using this unit in order to maintain a comparison with the amount of staff time used.

See Albert Schweitzer Foundation (n.d.) for a full list of their team members.

We distributed our culture survey to ASF’s 37 team members and 22 responded, for a response rate of 59%.

We recognize at least two major limitations of our culture survey. First, because participation was not mandatory, the results could be skewed by selection bias. Second, because respondents knew that their answers could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer, they may have felt an incentive to emphasize their employers’ strengths and minimize their weaknesses.

We distributed our culture survey to ASF’s 37 team members and 22 responded, for a response rate of 59%.

We recognize at least two major limitations of our culture survey. First, because participation was not mandatory, the results could be skewed by selection bias. Second, because respondents knew that their answers could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer, they may have felt an incentive to emphasize their employers’ strengths and minimize their weaknesses.

Our goal in this section is to evaluate whether each charity has a healthy attitude towards diversity, equity, and inclusion. We do not directly evaluate the demographic characteristics of their employees. There are at least two reasons supporting our approach: First, we are not well-positioned to evaluate the demographic characteristics of each charity’s employees. We ask some demographic questions on our culture survey, but respondents may not be representative of the entire staff. Second, we believe that each charity is fully responsible for their own attitudes towards diversity, equity, and inclusion, but the demographic characteristics of a charity’s staff may be influenced by factors outside of the charity’s control.

We use the term “diversity” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of any of the following characteristics: racial identification, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, ability levels, educational levels, parental status, immigrant status, age, and/or religious, political, or ideological affiliation.

There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that teams composed of individuals with different roles, tasks, or occupations are likely to be more successful than those which are more homogeneous (Horwitz & Horwitz, 2007). Increased diversity by demographic factors—such as race and gender—has more mixed effects in the literature (Jackson, Joshi, & Erhardt, 2003), but gains through having a diverse team seem to be possible for organizations which view diversity as a resource (using different personal backgrounds and experiences to improve decision making) rather than solely a neutral or justice-oriented practice (Ely & Thomas, 2001).