“Clean” Meat or “Cultured” Meat: A Randomized Trial Evaluating the Impact on Self-Reported Purchasing Preferences

Farmed animal products grown via a cell culture are often referred to as “cultured” or “clean.” For instance, a cell cultured meatball is often called a “cultured meatball” or a “clean meatball.” It is possible that one of these two terms may lead to greater consumer acceptance than the other one. If that were true, promoting that term over its alternative could be a highly effective way of helping animals. This is because a greater societal acceptance of cell cultured meat products could decrease the total demand for farmed animal products, sparing many individuals the horrors of industrial agriculture.

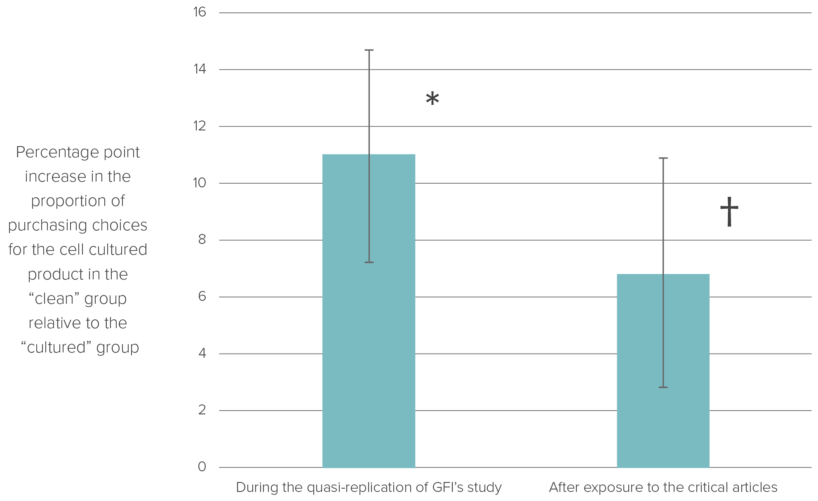

Last year we conducted a randomized trial in order to compare reported consumer acceptance levels of the “clean” and “cultured” names of cell cultured animal products. Our study had significant limitations (described in the latter part of this post) but we feel its results still provide some meaningful insights. In fact, the estimated effect size of the the “clean” name relative to the “cultured” name in the first part of the experiment was an 11 percentage point increase in the proportion of purchasing choices for the cell cultured animal product. In the second part of the experiment, participants were exposed to similar critical news pieces about cell cultured meat which differed in their use of “clean” vs “cultured” terminology. The proportion of purchasing choices for the cell cultured products by the “clean” group was 6.8 percentage points greater than that reported by participants in the “cultured” group. The remainder of this post will briefly review some relevant literature, and then will summarize our own study’s methods, limitations, and results, as well as our conclusions. Associated materials for this study can be found on the Animal Advocacy Data Repository.

Relevant literature

A number of informal polls on consumer acceptance of cell cultured meat have been completed.1 These polls may have quite large methodological flaws (such as unrepresentative samples or the possibility of the same individual voting numerous times) which should be taken into account during interpretation. More formal polls and surveys on the subject have also been completed by market research firms, non-partisan think tanks, and social scientists.2 Only some of those more formal polls and surveys provide an explanation of what cell cultured products are, and only a subset of those mention the benefits of cell cultured products. The polls and surveys which do not provide this information may poorly estimate the consumer acceptance levels of cell cultured animal products that should be expected in the future. This is because it seems likely that most future consumers will become somewhat informed about cell cultured products via sources like popular media reports, advertisements, or the products’ packaging—and that this additional information will likely affect consumer acceptance. Since we are more interested in the polls and surveys that we think more usefully reflect the consumer attitudes that we should expect in the future, the following brief overview of relevant literature only includes research that seemed to provide an adequate explanation of cell cultured products and seemed relatively unlikely to have large methodological flaws.

One such survey was a 2013 Flycatcher survey, for which we have not been able to closely examine the methodology because we haven’t found an English version of the full report. The summary of the survey reported that more than half of the Dutch population would like to try cell cultured meat, and that most thought it should not be called “cultivated meat.”3 Another survey by Hocquette et al (2015) reported that approximately 15% of respondents thought that cell cultured meat would be well accepted by consumers. Verbeke et al (2015) report that after being provided with some initial information about cell cultured meat, 24% of their sample were “surely” willing to try it, 19% were “surely” willing to purchase it and 14% were “surely” willing to pay more for it. Once the sample had heard of the environmental benefits and decreased risk of zoonosis, 43% were “surely” willing to try it, 36% were “surely” willing to purchase it and 36% of the consumers were “surely” willing to pay more for it. A recent survey by Wilks & Phillips (2017) reports that approximately 30% of their sample was willing to regularly eat cell cultured meat and that approximately 30% saw cell cultured meat as a replacement for farmed meat.

After a moderate literature search, we identified three studies that examined how consumer demand for cell cultured meat could be increased. A 2016 master’s thesis by van der Heide explored the effect of claims about cell cultured meat’s improved food safety, animal welfare benefits, and environmental friendliness on consumer expectations and willingness to try. However, the small sample size means the study’s results are inconclusive. Bekker et al (2017) report that providing consumers with information related to the sustainability of cultured meat positively influenced their attitudes towards it. To our knowledge, the only research that directly examined how the name of cell cultured products impacted consumer acceptance was a 2016 Good Food Institute (GFI) study. That study compared five names for cell cultured products and reports that using the terms “safe” and “clean” before the animal product’s name lead to significantly greater consumer acceptance than using “pure,” “cultured,” or “meat 2.0” as the term before the animal product’s name.

Methods

We decided to complete our study on this topic after being invited to a discussion with industry and nonprofit leaders about the naming of cell cultured products. In order to have results in time for that meeting, we spent a relatively short time developing our study’s methodology and materials. We now recognize that this was a mistake, and we think it significantly limited our ability to reach conclusive results. We will be devoting more time to future studies and will also be soliciting more feedback, as detailed in our recent blog post about our new research review process. Further information about this study’s limitations will be provided at relevant points in the remainder of this post.

We chose to quasi-replicate GFI’s study because we felt there was a reasonable chance that further experimental evidence on this topic would importantly inform the decision made at the forthcoming meeting. In our quasi-replication we only compared “clean” and “cultured” because it seemed that one of those terms was most likely to be chosen in the upcoming meeting as the predominant way of referring to cell cultured animal products in the near future.

For the quasi-replication, we recruited approximately one thousand participants using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and randomly assigned them into two groups. Those in the first group were shown a short and informative print news story about “cultured” meat. Participants in the second group were shown the same short news story but throughout the article “clean” was used instead of the word “cultured”. These articles were the same as those used in GFI’s study.

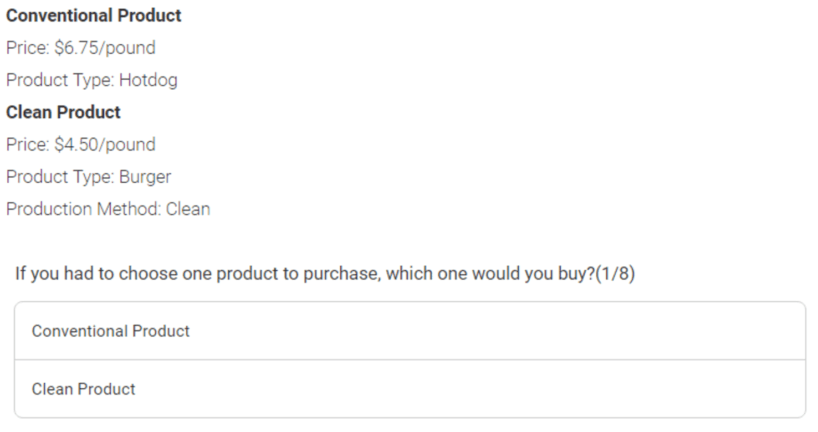

After having time to read the article assigned to them, participants responded to eight hypothetical purchasing scenarios. In these scenarios participants in the clean group saw products with the “clean” name alongside a conventional or a humane product, and participants in the cultured group saw products with the “cultured” name alongside a conventional or a humane product. The type, price, and production method of each product included in the purchasing scenarios was randomly selected.

This randomization was such that:

- The products were either both beef or both chicken,

- Each of the scenarios had only one cell cultured product, and

- The specific product type and price were selected from specified lists.4

For all these purchasing scenarios participants reported how likely they were to buy each product on a scale from 1–7 and if they had to choose one of the products to purchase, the one that they would buy. This number and type of purchasing scenario are the same as that used in GFI’s study.

We then explored how similar critical news pieces impacted participant’s reported purchasing preferences. This was of interest to us because it seemed likely there would be critical news pieces in the near future, and there could be importantly different impacts of those articles for the different names of cell cultured meat. Some deliberate differences5 in the critical news pieces for the “cultured” and “clean” groups were included because we thought that the “clean” terminology would generate some specific criticisms that the “cultured” terminology would not. All of the articles used in the experiment can be found on the Animal Advocacy Data Repository.

After having time to read their assigned critical article, participants again completed eight purchasing scenarios. The products included in these scenarios were selected by the same algorithm used to select the products shown in the first round of purchasing scenarios.

Results

Due to an error on our part, the survey program did not record (in a way we could interpret) participants’ responses to how likely they were to buy products on a 1-7 scale, and the production method and the prices of products used in the purchasing scenarios. Again, this most likely was a consequence of the limited time we allocated to this experiment. The inadequate recording meant the study provided significantly less information about consumer preferences than it otherwise would have. Since we were unable to include those inadequately recorded results and variables in our analysis, we focus only on the results of the purchasing choice where participants had to choose one of the available products to buy.

For the purchasing decisions in the quasi-replication, 52.4% of the 3,952 choices in the “clean” group chose to purchase the “clean” meat product, while 41.4% of the 4,016 choices in the “cultured” group chose to purchase the “cultured” meat product. To determine if this difference was statistically significant we used a binary logistic regression model that made use of the generalized estimating equation to account for the clustering in the data. In the purchasing decisions after participants had time to read the critical news article, 40.0% of 3,952 choices made in the clean group selected the clean meat product, while 33.2% of the 4,016 choices in the cultured group selected the cultured meat product. We again fitted a binary logistic regression model that made use of the generalized estimating equation to determine if there was a significant difference in the choices of the two groups. The results of most interest from fitting these regression models are shown in Figure 3 and communicated in the notes of that figure.6

Notes:

The error bars in Figure 3 represent 95% confidence intervals.

(*) The point estimate of the percentage point increase in this case was 11 with a 95 confidence interval of 7.2–14.7. The corresponding odds ratio was 1.56 with a 95% confidence interval of 1.34–1.81.7 The p-value of this result was p<0.0001.

(†) The point estimate of the percentage point increase in this case was 6.8 with a 95 confidence interval of 2.8–10.9. The corresponding odds ratio was 1.34 with a 95% confidence interval of 1.13–1.59.8 The p-value of this result was p<0.001.

Conclusions

The instructions given to the survey program meant that important information about participants’ purchasing preferences—as well as the product type and the product prices included in the purchasing scenarios—were not recorded in a way that we could interpret. This was a large flaw in the study and we feel that we likely would have avoided these problems if we had spent more time on the study design. Despite those limitations, we still feel that the results are a valuable indication of how consumers respond to the “clean” and “cultured” names of cell cultured animal products.

Compared to the “cultured” name, the “clean” name led to significantly greater consumer acceptance of cell cultured meat. The estimated effect size of the the “clean” name relative to the cultured name in the first part of the experiment was an 11 percentage point increase in the proportion of purchasing choices for the cell cultured animal product. This is similar to the approximately eight percentage point increase in the proportion of purchasing choices for the cell cultured animal product reported in GFI’s study for “clean” meat relative to “cultured” meat. We think that the available experimental evidence on this topic now at least moderately suggests that the “clean” name leads to significantly greater consumer acceptance of cell cultured animal products than the “cultured” name in these purchasing scenarios.

It seems plausible that the “clean” critical article led to a greater absolute decrease in consumer acceptance than the “cultured” critical article. This is because after exposure to the critical article, the point estimate of the effect size for assignment to the “clean” group went from 11 to a still significant 6.8 percentage point increase in the proportion of purchasing choices for the cell cultured animal product. When we initially designed this experiment we thought that the differences9 in the critical articles usefully captured likely differences that would occur if one or the other of these names was predominantly used to refer to cell cultured meat. As a consequence, we felt the results from the second part of the experiment may tell us how the consumer acceptance associated with the different names of the products would change in response to the type of criticisms that were likely to be raised in a critical news article.

However, we now feel there are at least two large limitations to the second part of this study. Firstly, differences in the critical articles apart from the “clean” and “cultured” terms prevent wholly attributing the possibly different impacts of the critical news pieces to the names of cell cultured meat used in the critical articles. Secondly, some quite effective criticism specific to one name may not have been included in the critical article and so the results do not fully answer whether one of the names could be more effectively criticized than the other. Further research may wish to examine both what methods lead to initially greater consumer acceptance of cell cultured animal products and to ensure that those methods still result in greater consumer acceptance of cell cultured meat after likely criticisms are taken into account. Due to the limitations of the second part of this study, we did not attempt to draw any conclusions about the possible differential effects of criticisms on the different names of cell cultured meat.

While the available experimental evidence on this topic now at least moderately suggests that in the context that they have been studied the “clean” name leads to greater consumer acceptance than the “cultured” name, there are still various other arguments for and against the different terminologies. A full discussion of all those arguments is outside the scope of the present blog post. We currently do not have a formal position on which term is most effective for other groups to promote. ACE’s present policy is to use the term “cultured” and/or “cell cultured” in our content and the decisive reasons for this were the greater clarity of these terms and their more common use among neutral sources. However, we are closely monitoring the situation, and our policy and/or our views about the terms could update as we come across further information and spend more time reflecting on the matter. We greatly look forward to further research and discussions about the specific terminologies or other methods that can be used to increase consumer acceptance of cell cultured products so that we can reach a more certain view about which ways of promoting cell cultured products best help animals.

These informal polls include: Guardian (2012), Guardian (2013), Guardian (2014), Attn (2016), Daily Mirror (2016), Harris (2016), Institute of Environmental Sciences (2017) and ITV News (2017).

These polls and surveys from more reputable sources include: European Commision (2005), YouGov (2012), Flycatcher (2013), Pew Research Centre (2014), Hocquette et al (2015), Verbeke et al (2015), Harris Interactive (2016), Wilks & Phillips (2017)

“Cultivated meat” is the term that was reported in Flycatcther’s english summary of the study. However, it seems that the study used the word “kweekvlees,” which Google Translate and a Dutch associate of ours actually translated as “cultured meat.” We are currently unsure what the best translation of the term used in this study is.

The possible product types for beef were burger, meatball, hotdog, ground beef. The possible prices for these products were $2.75/lb, $4.50/lb, $6.75/lb, $9.00/lb. The possible product types for chicken were chicken finger, chicken nugget, ground chicken and chicken patty. The possible prices for these products were $1.50/lb, $2.50/lb, $3.75/lb and $5.00/lb.

The headline of the critical news article shown to the “clean” group was “‘Clean meat’ or ‘unclean meat’? Critics bash activists for ‘misleading’ term” and the headline of the article for those in the “cultured” group was “Critics bash activists for promoting cultured meat.” Some concerns promoted in the “cultured” critical article that were not promoted in the “clean” critical article were concerns about “cultured” meat being promoted as the healthy choice. Likewise, some of the concerns promoted in the “clean” critical piece that were not raised in the “cultured” critical article centered on the “clean” naming system.

The R code used in these analyses can be found on the Animal Advocacy Data Repository.

Effect sizes found with binary logistic regression are often expressed as an odds ratio. In this case, the odds ratio represents the odds an individual in the “clean” group would select the cell cultured product, divided by the odds that participant in the “cultured” group would select the cell cultured product. An odds ratio significantly greater than one indicates that, relative to assignment to the “cultured” group, assignment to the “clean” group increases the probability of selecting the cell cultured product.

Effect sizes found with binary logistic regression are often expressed as an odds ratio. In this case, the odds ratio represents the odds an individual in the “clean” group would select the cell cultured product, divided by the odds that participant in the “cultured” group would select the cell cultured product. An odds ratio significantly greater than one indicates that, relative to assignment to the “cultured” group, assignment to the “clean” group increases the probability of selecting the cell cultured product.

The headline of the critical news article shown to the “clean” group was “‘Clean meat’ or ‘unclean meat’? Critics bash activists for ‘misleading’ term” and the headline of the article for those in the “cultured” group was “Critics bash activists for promoting cultured meat.” Some concerns promoted in the “cultured” critical article that were not promoted in the “clean” critical article were concerns about “cultured” meat being promoted as the healthy choice. Likewise, some of the concerns promoted in the “clean” critical piece that were not raised in the “cultured” critical article centered on the “clean” naming system.

About Kieran Greig

Kieran’s background is in science and mathematics, his core interest is effective altruism, and he joined the team as a Research Associate in 2017.

ACE is dedicated to creating a world where all animals can thrive, regardless of their species. We take the guesswork out of supporting animal advocacy by directing funds toward the most impactful charities and programs, based on evidence and research.

Join our newsletter