HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2016 |

| Current Version | November, 2018 |

Archived Version: November, 2016

This review was edited on January 31, 2018 to remove information that we no longer believe to be accurate about the leadership and culture of HSUS. We explain our most recent thinking about HSUS FAPC on our blog. See our most recent review of HSUS FAPC for more information.

What does the HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign do?

The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) works on behalf of a large variety of animal causes, including but not limited to: companion animals, wild animals, animals used for entertainment, animals used in laboratories, and farmed animals. For the purpose of this review, we examined their work on behalf of farmed animals.

The two primary goals of the HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign (FAPC) are (i) combating the most extreme confinement practices and abuses in the animal agribusiness system, and (ii) reducing total demand for animal products. They work with animal product producers to implement improvements in the treatment of animals used for food. They lobby for better laws, fight ag-gag legislation, and engage in campaigns to rid factory farms of the worst animal abuses. They sometimes conduct investigations of factory farms. FAPC promotes Meatless Monday campaigns in businesses, health organizations, and educational institutions.

What are their strengths?

As HSUS is one of the largest and most recognized animal protection organizations in the United States, they are frequently covered in the media and thus able to reach very large numbers of people through their work. Additionally, HSUS FAPC takes a strategic approach to implementing change. They recognize that large changes can’t always be achieved overnight, so they work to meet goals that are attainable as well as significant. They have a strong track record in legal work, corporate outreach, and institutional meat reduction programs.

What are their weaknesses?

Our primary concern about FAPC is that they are part of a larger organization, HSUS. It was difficult for us to ascertain exactly how much funding for FAPC activities comes directly from their own budget rather than the general budget of HSUS. Since it seems that many of FAPC’s best efforts are aided by the large overall budget of HSUS, it is difficult to ascertain how much money is actually being spent to achieve success with their efforts. It is also unclear whether donations not large enough to fund a program or position would be entirely fungible, or whether they would indeed be used in the FAPC department as additional marginal funding.

Why didn’t HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign receive our top recommendation?

We see FAPC as having many strengths and engaging in high quality work on a consistent basis, and we endorse many of their strategies. However, we have serious concerns about the organization’s culture. We explain our most recent thinking about HSUS FAPC on our blog.

This review was edited on January 31, 2018 to remove information that we no longer believe to be accurate about the leadership and culture of HSUS. We explain our most recent thinking about HSUS FAPC on our blog. We intend to update the full review in November 2018.

Table of Contents

- How HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign Performs on Our Criteria

- Criterion #1: The Charity Has Concrete Room For More Funding and Plans For Growth

- Criterion #2: A Back-of-the-Envelope Calculation Finds the Charity is Cost-Effective

- Criterion #3: The Charity is Working on Things That Seem to Have High Mission Effectiveness

- Criterion #4: The Charity Possesses a Robust and Agile Understanding of Success and Failure

- Criterion #5: The Charity Possesses a Strong Track Record of Success

- Criterion #6: The Charity has Strong Leadership and Long-Term Strategy

- Criterion #7: The Charity has a Healthy Culture and Sustainable Structure

- Criticism/FAQ

- Supplementary Materials

How HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign Performs On Our Criteria

Criterion #1: The Charity Has Concrete Room for More Funding and Plans for Growth

In 2014 we said that the HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign could use more funding to expand their programs, especially their work on Meatless Monday and other institutional meat reduction policies. In the past two years, our estimate for their overall budget has grown by about $2.5 million, and they’ve greatly expanded the number of people working on institutional meat reduction, from 4 to around 20. There has also been some growth in the number of policies enacted because of that program, although it has not directly led to proportionally larger policy outcomes. However, this may be in part due to FAPC choosing to spend more time on institutional meat reduction projects with less easily measurable results, such as trainings for institutional chefs.

FAPC still plans to add staff; currently they would like to increase the number of people working on involving shareholders in corporate policy change by asking investors to vote with HSUS on policy changes or call companies on FAPC’s behalf. They recently received a $500,000 grant to expand their corporate work through advertising, such as newspaper ads and TV commercials, but having more approaches available can help with tough campaigns.

FAPC is already part of a much larger organization, and has roughly tripled in size since we reviewed them in 2014. Even though there’s potential concern about decreased efficiency in the institutional meat reduction program during this period of rapid growth, we think that FAPC has overall handled its growth well and has continued to do very effective work. We think they can probably continue to grow by at least 5-10 employees per year while maintaining the quality of their work.

However, because FAPC is a part of HSUS and we do not think all of HSUS’ other activities are as effective as FAPC’s, we have concerns about their ability to use individual donations. In particular, while FAPC’s growth over the past two years is very persuasive for their ability to use funds restricted to creating new positions within FAPC to actually create those new positions, we think that smaller donations may be hard to restrict sufficiently and could effectively end up funding HSUS’ other work. This is why we’ve expressed our estimate of FAPC’s room for funding in terms of positions instead of dollars, as we do for other groups; we don’t think a few large donations and a large number of small donations are equivalent in this case.

All things considered, we only recommend making restricted donations to FAPC in larger amounts, i.e. large enough to fund a specific campaign or another employee position, especially as we are unsure to what extent funds donated to FAPC more generally are fungible with general HSUS funds. If you are considering a donation to the HSUS FAPC, we encourage you to restrict your donation to the FAPC or even more specifically to a particular program. We also recommend contacting Josh Balk to discuss specifics.

Criterion #2: A Back-of-the-Envelope Calculation Finds the Charity is Cost-Effective

HSUS FAPC’s budget is particularly challenging to understand, since they are part of a much larger organization. Some of their activities are funded through the FAPC’s budget, while others receive some funding from other sources within HSUS. Furthermore, the fact that HSUS is a large and well-known organization means that FAPC, working as part of HSUS, has more influence than would an independent organization with the same budget. However, it would not be accurate to calculate cost-effectiveness as though FAPC had the entire budget of HSUS at their disposal. We estimate that FAPC’s annual budget is around $3.5 million, based on the campaign expenses we know about. Note that all estimates factor in associated supporting costs including administrative and fundraising costs. Where we give estimates as ranges, they represent our 90% subjective confidence intervals; that is, we expect the true value to be within the range given in 90% of cases.1

We think this quantitative perspective is a useful component of our overall evaluation, but the estimates of equivalent animals spared per dollar should not be taken as our overall opinion of the charity’s effectiveness, especially given that we choose not to account for some less easily quantified forms of impact in this section, leaving them for our qualitative evaluation.

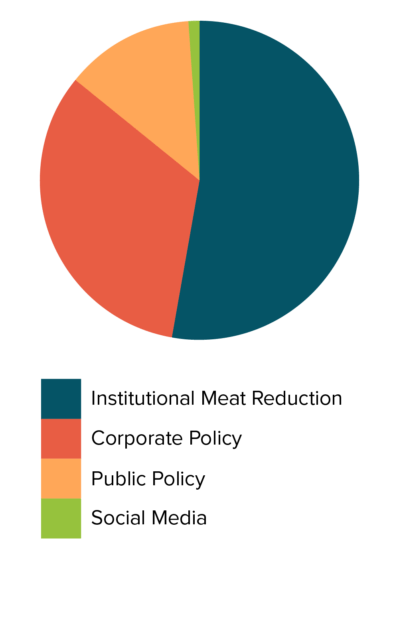

Institutional Meat Reduction

We estimate that in 2016 FAPC will spend about 53% of their budget, or $1.8 million, on Meatless Mondays promotion and other institutional meat reduction programs. We expect this to result in approximately 60 to 100 school districts and other organizations adopting institutional meat reduction policies ranging from increased availability of vegetarian options on Mondays, to fully meatless Monday menus, to dining stations in cafeterias that serve only plant-based food every day of the week. We also expect them to train between 400 and 600 chefs in preparing plant-based foods.

Corporate Policy

We estimate that in 2016 FAPC will spend about 33% of their budget, or $1.1 million, on corporate policy change, mostly but not exclusively working with corporations to implement stronger animal welfare standards in their supply chains. We estimate that FAPC’s corporate outreach will help cause between 85 and 100 policy changes affecting between 300 million and 1.1 billion laying hens and broiler chickens, accounting for the risk that some companies might not follow through with their commitments. The policies include moving laying hens to cage-free systems and welfare improvements for broiler chickens that affect slaughter conditions, access to sunlight and perches, and possibly the use of chicken breeds less prone to health problems.

Public Policy

We estimate that in 2016 FAPC will spend about 13% of their budget, or $450,000, on public policy, including advocacy for strengthened animal protection and against ag-gag bills. This does not reflect the full amount that HSUS as a whole has spent on public policy relevant to farmed animals in 2016; HSUS has contributed over $1 million to the campaign for a ballot initiative in Massachusetts regarding the treatment of farmed animals, and our impression is that this funding did not come from FAPC’s budget. (We could adjust our estimate of FAPC’s budget to include this amount, since it’s public knowledge, but we think it’s probably typical of a pattern in which FAPC conducts a part of HSUS’ public policy work dealing with farmed animals, but HSUS also has public policy specialists and other funding available for specific campaigns. In general we have very little sense how much HSUS spends on farmed animal issues outside the FAPC’s budget, so we’re choosing to point out the complexity of the situation rather than attempt to completely resolve it.) In 2016, we expect FAPC to have helped defeat around 4 ag-gag and right-to-farm bills in various states, and to have played a very substantial role in the campaign for Question 3 in Massachusetts, which prohibited knowingly confining—with some exceptions—pigs, veal calves, and egg-laying hens in a way that “prevents the animal from lying down, standing up, fully extending its limbs, or turning around freely,” and prohibited the sale of products from animals confined in this way, regardless of where they were raised (also with some exceptions).

Social Media

Finally, we estimate that in 2016 FAPC will spend under 1% of their budget, or about $16,000, on social media outreach, including their Facebook page. We estimate that this year the videos they share will get between 400,000 and 600,000 unique views to 95% of the video length. This gives us a cost of between $0.03 and $0.04 per video view to 95%. However, we note that users also engaged with FAPC’s content in other ways, such as watching parts of videos and reading text posts, so the cost per engagement is lower.

Changes Since 2014

Since we last reviewed FAPC in 2014, their budget for institutional meat reduction has grown considerably, with much slower growth in the number of policies they’ve helped to put into place. As a result, it seems likely to us that the real cost-effectiveness of this program has decreased, at least in terms of its direct impact. Our estimate below of the number of animals spared by the program, however, has remained largely constant. This is because in 2014 the institutional meat reduction program was extremely new, and we had low confidence that the typical institution would choose to stick to the policy developed with HSUS over the course of the following several years. Now, however, that program has a longer track record, and we have been able to check that at least some major institutions have retained meat reduction policies implemented in 2012 or 2013.

All Activities Combined

To combine these estimates into one overall cost-effectiveness estimate, we need to translate them into comparable units. This will introduce several sources for errors and imprecision, so the resulting estimate should not be taken literally. However, it will provide information about whether FAPC’s efforts are comparable in efficiency to other charities’.

We use FAPC’s estimate of the number of meals affected yearly by institutional meat reduction policies, together with our estimate for the number of animals spared from life on a farm by one person avoiding meat for a year, to estimate that FAPC spares between 0.1 and 4 animals per dollar spent on institutional meat reduction programs.

We estimate the number of animals affected by FAPC’s corporate policy victories, the extent to which FAPC worked with other groups to achieve those victories, and the proportion of suffering alleviated by the policy changes to estimate that FAPC spares an equivalent of between -300 and 1000 animals per dollar spent on corporate policy work.2, 3 Note that even though many of our ranges are quite wide, this one is exceptionally so. We attribute this largely to the substantial uncertainty we have in the change in animal welfare caused by Perdue’s new policies.

We exclude public policy results from our final cost-effectiveness estimates and don’t attempt to convert them into an equivalent animals spared figure; it is too difficult to disentangle FAPC’s effects from those of other parts of HSUS and those of other advocacy groups. In some cases, as with ag-gag laws, it is also very difficult to confidently estimate any short-term impacts on animal suffering.

We use our social media calculator to estimate that FAPC spares between 0.2 and 4 animals per dollar spent on social media programs.4

We weight our estimates by the proportion of funding FAPC spends on each activity to estimate that in the short-term, FAPC spares between -100 and 400 animals per dollar spent.5 We have also run parallel calculations to estimate that this means FAPC spares animals between -20 and 100 years of suffering on farms per dollar spent. Because of extreme uncertainty even about the strongest parts of our calculations, there is currently limited value in further elaborating these estimates. Instead, we give weight to our other criteria. We also exclude more indirect or long-term impacts from this estimate, which could result in it being an underestimate of overall impact. Because charities have varying proportions of different types of impact, this makes our quantitative estimates particularly difficult to use in comparing charities.

Criterion #3: The Charity is Working on Things That Seem to Have High Mission Effectiveness

Promoting Legislation to Improve Living Conditions for Farmed Animals

FAPC’s legal work to improve living conditions for farmed animals includes attempts to eliminate the use of gestation crates for pigs, veal crates for calves, and battery cages for chickens. FAPC has also worked to prohibit the force-feeding of ducks for foie gras and the tail docking of cows. Since achieving legal protections for animals would improve living conditions for animals on all farms covered under that law, we see legal work as a potentially highly cost-effective way to help a large number of animals. It’s possible that achieving small legal protections for animals might also influence public attitudes, either positively (e.g. by raising awareness of animal welfare) or negatively (e.g. by legitimizing the use of animals).

Combating Attempts to Pass Ag-Gag Laws

FAPC works to prevent states from adopting ag-gag laws. Ag-gag laws make it much more difficult for groups to conduct undercover investigations. Since we think that undercover investigations are valuable, we also think that defeating ag-gag laws has the potential to do substantial good for farmed animals.

Corporate Outreach

Corporate outreach seems to have high mission effectiveness because it involves convincing a few powerful people to make decisions that influence the lives of millions of animals. This seems likely to be easier than reaching and persuading millions of consumers in order to accomplish the same goal. However, the gains achieved through corporate outreach are often small welfare improvements. It’s not clear whether such improvements, even if easy to achieve, are highly effective in the long term. Small welfare reforms may improve conditions for animals, but they may also influence public opinion, either towards greater concern for farmed animals or towards complacency with regard to industrial agriculture. We expect the impact on public opinion to be favorable for animals, overall.6

Meatless Monday Campaigns in Institutions, Hospitals, and Schools

We think Meatless Monday campaigns have high potential to create a large amount of change. The immediate impact of a successful campaign is apparent; hundreds of thousands of meals each week are served without meat. The broader impact is uncertain, but likely to be positive. While there is a possibility that people are eating more meat on other days of the week to make up for not having meat on Monday, we find that to be unlikely. Rather, we believe that, by promoting a discussion about eating choices and demonstrating that meat is not a necessary part of a meal, Meatless Mondays will likely cause reduced meat consumption.

Training Food Service Professionals

FAPC trains chefs to prepare vegan food and works with institutions to create vegan menus. Helping with vegan menus seems likely to create change by reducing the amount of meat served in institutions. The magnitude of the change depends on the popularity of the vegan menus among consumers and the length of time that the institution implements the menu. We have little information about either of these factors. Similarly, training chefs to prepare vegan food may create change by encouraging the chefs to serve less meat, but we have little information about the magnitude of the change. To our knowledge, there is little evidence available about precisely how much chefs change their practices as a result of the trainings or the length of time for which they maintain those changes.

Promoting Animal Protection Through Media Exposure

FAPC uses HSUS’ large reach to bring their message to a wide audience through action alerts, social media posts, interviews, and Youtube videos. These exposures seem especially valuable because they reach such a large number of individuals for a flat investment. Because there is weak evidence of a negative correlation between media coverage of animal welfare and meat consumption, we think that gaining media exposure may be an effective intervention. We hope to see more research in this area.

Criterion #4: The Charity Possesses a Robust and Agile Understanding of Success and Failure

FAPC measures the immediate impact of their programs when possible. For example, they track the effects of their corporate victories and the amount of meat reduction caused by their Meatless Monday program in order to estimate the number of animals spared. They have found that simply meeting with individual dining Directors is an effective strategy for promoting their meat reduction program. They’ve streamlined the process by implementing Food Forward, an educational program which sometimes brings together dozens of dining and purchasing Directors at the same time.

FAPC chooses to focus on institutional change in part because it is easier for them to track how successful they’ve been in affecting animals when they influence corporate, public, or institutional policy than when they affect individual behavior. They aim to measure their success through the tangible effect that they have on animals by reducing meat consumption or improving welfare standards. However, many of FAPC’s programs have effects that are more difficult to measure than the effects of their meat reduction program or corporate work. FAPC tracks the litigation they pass, the media attention they generate, and the number of food service professionals they train. They solicit feedback after the trainings, but they have not undertaken many attempts to understand the impact of their training programs on animals.

Criterion #5: The Charity Possesses a Strong Track Record of Success

Have programs been well executed?

Notable achievements since FAPC’s founding in 2005 include leading successful legal campaigns to ban inhumane practices, encouraging companies to eliminate gestation crates and battery cages, mobilizing investments in plant-based foods, and convincing institutions, including dozens of school districts, to implement Meatless Mondays.

FAPC works to prevent ag-gag bills from becoming laws; in 2015, they defeated all but one that they fought, a total of nearly 30. Without their work on this front, it would be much more difficult for FAPC and other charities to conduct undercover investigations in the United States.

FAPC was instrumental in passing and subsequently defending California’s Proposition 2, which took effect in 2015 and requires farmed animals in California be able “to lie down, stand up, fully extend their limbs and turn around freely.” They recently worked on a ballot measure in Massachusetts that prohibits confining pigs, veal calves, and egg-laying hens in a way that “prevents the animal from lying down, standing up, fully extending its limbs, or turning around freely,” with some exceptions. It also prohibits the sale of products from animals confined in this way, regardless of where they were raised, with some exceptions. The announcement of the Massachusetts ballot initiative has helped HSUS secure cage-free commitments from major corporations. Last year, McDonald’s announced that it would work with HSUS to implement a cage-free timeline, which seems to have triggered a series of similar commitments from other companies.

While FAPC focuses primarily on influencing corporate and public policy rather than individual attitudes, they have had some success in the creation and promotion of educational videos. For example, they recently set up and filmed a stand in New York advertising “free chicken.” When people approached expecting food, the HSUS activists produced a live chicken. The video has been viewed approximately 636,000 times on HSUS’ Facebook page, and those views approximately doubled when the video was picked up by Upworthy. Their anti-gestation crate video has been viewed approximately 1.5 million times on Youtube.

Have programs led to change for animals?

FAPC’s work has significantly and positively affected the lives of animals.

FAPC bears a large portion of the responsibility for securing cage-free commitments that could affect the lives of billions of hens living in factory farms. Partly as a result of Proposition 2, Aramark, Sodexo, and Compass Group will transition to cage-free liquid egg supplies. HSUS reports that these commitments will affect 3.5 million hens.

The meat reduction policies that FAPC has worked to implement in 2015 within schools and hospitals will result in about 20 million meat-containing meals being replaced by meatless meals. This change will reduce the demand for animal products; we estimate that it will spare between 100,000 and 900,000 animals from being used and killed in factory farms.7 We hope that FAPC’s work to influence investments in the plant-based food industry will also help to reduce the demand for animal products by improving the available alternatives.

Criterion #6: The Charity Has Strong Leadership and Long-Term Strategy

Leadership

FAPC is unique among charities we review in that they are supported by the leadership, overarching strategy, and resources of HSUS. This has potential benefits and costs: FAPC can utilize the name recognition and membership base for its campaigns, while the structure could also make coordination difficult and increase bureaucratic inefficiency.

HSUS’ board seems to be composed of highly respectable and capable professionals from a variety of backgrounds. It is also our impression that HSUS has more strongly prioritized farmed animal advocacy since Wayne Pacelle joined as CEO in 2004 and since the current Board Members joined, which we see as a very positive strategic choice.

Long-Term Strategy

While we believe all animals should be free from suffering, the animal protection movement currently has limited resources and has to make tough trade-offs between different interventions to help animals. Because we currently think helping farmed animals is the most promising cause area for most donations, other things being equal, we are relatively more excited about the work of FAPC compared to other HSUS programs. However, we understand that HSUS takes “a mainstream approach” and plays an important role in the animal movement, helping people connect more obvious forms of cruelty, such as a dog left on a chain without food and water, with less obvious forms that affect many more animals, such as the confinement of farmed animals. All things considered, we think HSUS should expand its farmed animal program, but not shift all its resources towards that area.

FAPC used to maintain a strategic plan, but found that their approach needed to change so quickly that the plans were not worth the significant cost of writing them. For example, FAPC has made progress for egg-laying hens and chickens raised for meat much more quickly than expected over the past two years. While we don’t think having a strategic plan is the most important indicator of clear strategic thinking, we think it does help organizations achieve medium- and long-term goals by coordinating their programs.

We are excited about FAPC’s institutional approach towards change for farmed animals. In our limited research into the most effective animal interventions, we have identified corporate outreach for better animal welfare policies as very promising. We are also excited about FAPC’s work on reduction of animal product consumption in school districts, hospitals, and other institutions. Overall, we currently see changing institutions as a potentially high-impact approach to helping farmed animals, although research on this topic is limited.

Criterion #7: The Charity Has a Healthy Culture and Sustainable Structure

New employees are given a standard HSUS orientation as well as a FAPC-specific orientation. They are made aware of standard procedures and educated on the history of FAPC. Additionally, FAPC makes an effort to continue staff development through internal presentations and discussions about effectiveness and other related concepts, and through offering internal feedback. We appreciate these efforts, as it shows they value self-improvement and are consistently examining their own work. FAPC has also shown steady financial growth, indicating financial stability; however, this is challenging to fully understand given FAPC’s position within HSUS, a large and very stable organization with its own strategic priorities with which we are less familiar.

FAPC was forthcoming with the information we needed for our review, even though it is particularly challenging for them to gather this information because of their status as a part of HSUS rather than being their own organization. Some of FAPC’s expenditures are from dedicated funds, but others come out of more general HSUS budgets for advertising or office space. It may be legitimately difficult for FAPC to know the total amounts of resources they use because of this funding structure.

FAPC publishes a timeline of their campaign highlights online, and offers to talk about what they are doing when asked. Many of their efforts are public; the ones that are confidential are kept that way so as not to hinder their success. FAPC often has conversations with other advocates on what works and what doesn’t work, and they meet regularly with frequent collaborators, such as through their recent work on the Massachusetts ballot initiative.

Criticism/FAQ

Does FAPC worry that focusing on some of the most extreme confinement practices could lead to complacency with other forms of suffering farmed animals endure or with meat consumption?

Critics argue that welfare reforms (e.g. bans on battery cages) might lead people to think that farmed animals no longer suffer and that helping them is no longer a priority.8 Some cite as evidence that the animal agriculture industry markets itself as humane and ethical, which suggests this messaging actually benefits those companies.9 However, this may only reflect gains to individual companies from positioning themselves as the most humane option.10 There isn’t much evidence that this kind of marketing helps the industry as a whole, and there’s weak evidence of a negative correlation between media coverage of animal welfare and meat consumption.

Since welfare reforms often involve working directly with food industry companies, this can give the public the impression that these companies treat their animals well when this is not the case, especially when animal advocates are incentivized to make the humane reforms seem like drastic improvements when animals still suffer substantially.11 Critics would also argue that, empirically, welfare reforms such as banning battery cages reduce only a very small portion of the harm of animal agriculture, if any, so they are not the most cost-effective use of time.12, 13, 14

HSUS has not seen evidence of increased complacency among corporations as a result of their achievements thus far, as companies have often been more willing to work with them after making progress on some issues. It’s not clear whether they would be aware of increased complacency among consumers as a result of their work.

As activists and potential activists notice HSUS’ progress, the animal advocacy community grows and can push for better animal welfare policies in the future. Also, making institutional progress for animals could increase the credibility of the animal advocacy movement, as it becomes clear that animal advocates are not just passionate about changing their personal diets; they are also capable of making significant institutional changes.15

The success of welfare reforms also establishes moral discussions of animal agriculture as an important and tractable topic in the public domain, which seems important for further progress. It may even be important for facilitating the transition to vegan alternatives, like cultured meat. Consumers may support alternatives to animal agriculture more enthusiastically if they are aware of a history of other attempts to reform the system.

Why does FAPC favor institutional meat reduction over individual meat reduction using tactics such as leafleting and online ads?

FAPC attempts to reduce meat consumption through addressing institutional policies, rather than the more common method of using leaflets, ads, or other outreach to ask individuals to reduce their meat consumption. Critics could argue that one of the most important reasons to convince individuals to go vegan or vegetarian is that this grows the animal advocacy movement by creating a sympathetic audience and a source of supporters for other programs. While institutional meat reduction could lead people to eat less meat, if this change isn’t noticeable to them or something they feel a connection with, it may not make them any more supportive of animal advocacy.

FAPC says that institutional meat reduction is a cost-effective and reliable way to reduce meat consumption. While it is difficult to determine how much dietary change is induced by outreach to individuals, FAPC is often able to obtain a clear understanding of how much less meat institutions purchase when they implement meat reduction policies.

We consider FAPC’s choice of institutional strategies a trade-off, obtaining greater reliability (and possibly efficiency) in reducing demand for meat in the short-term in return for possibly reduced effects on attitudes towards animals. While people who participate in institutional Meatless Monday programs or similar meat reduction efforts may increase their skills related to eating a plant-based diet and their openness to animal advocacy messages, the effect on attitudes may be smaller than similar effects from individual-focused outreach like leafleting.

Why does FAPC (and HSUS in general) invest so heavily in influencing policy through ballot initiatives, which are very expensive on a per-initiative basis? Have they considered alternatives which might be cheaper, such as lobbying representatives or even administrative agencies such as the USDA?

Critics might point to the high cost of ballot initiatives as an indication that they are unlikely to be among the most cost-effective ways to help animals. Even within the area of public policy, there are many opportunities to influence decisions, and some of these may be cheaper than passing initiatives, which usually requires both an extended phase of gathering signatures on the initiative and an expensive public campaign to win votes. FAPC could instead lobby elected officials to write and vote for laws similar to the ones they pass through initiatives, as they lobby them to block ag-gag legislation. Alternatively, they could try to influence policy through government agencies like the USDA, which has some control over animal welfare policy and which other groups have tried to influence through various means, sometimes successfully.

FAPC says that while ballot initiatives are expensive, they also have benefits that other methods of influencing public policy lack. They attract more media coverage and do more to educate the public than other methods do. They also unite and energize advocates who work on them, because they require a large campaign. Finally, the types of reforms that are achieved through ballot initiatives have not been achieved in the U.S. through other means.

We aren’t sure whether ballot initiatives are in general more or less cost-effective than other methods of influencing public policy. We think that if similar legislation could be passed through lobbying elected officials in the U.S., HSUS would likely be trying or have tried to do so, given their familiarity with those methods from other campaigns. As is clear from the amount of ag-gag legislation that has been proposed, and from U.S. policy generally when compared to European agricultural policies, the animal industry has significant influence over legislators, and directly overcoming that influence enough to pass significant protective legislation seems unlikely to be cheap and may be outside the ability of the current animal advocacy movement. We are more optimistic about advocacy groups’ ability to influence policy through agencies, and we think it might be a positive development for FAPC to become more involved in that area.

Additionally, our impression is that much of the ballot initiative funding comes from non-FAPC HSUS spending, which suggests that marginal donations to FAPC are contributing more to activities other than the ballot initiatives.

The method we use does calculations using Monte Carlo sampling. This means that results can vary slightly based on the sample drawn. Unless otherwise noted, we have run the calculations five times and rounded to the point needed to provide consistent results. For instance, if sometimes a value appears as 28 and sometimes it appears as 29, our review gives it as 30.

Sometimes our estimated cost-effectiveness ranges include negative numbers if we are not certain that an intervention has a positive effect, and it could have a negative effect, even if we think that isn’t likely. This doesn’t mean we think those interventions are equally likely to harm animals as to help them, unless the range is equally large on either side of zero.

From our five computations, the ranges were: -330 to 1100, -370 to 1100, -320 to 1400, -330 to 1300, and -320 to 1200.

From our five computations, the ranges were: 0.16 to 4.2, 0.16 to 3.4, 0.16 to 3.9, 0.16 to 3.7, and 0.18 to 4.

From our five computations, the ranges were: -100 to 390, -110 to 440, -100 to 460, -120 to 380, and -110 to 370.

There have been at least two Mechanical Turk experiments investigating the short-term impact of viewing information about recent welfare reforms on attitudes towards animal consumption. Both studies (one by MFA and another by Jacy Reese, who was a Board Member at ACE at the time of the study) showed statistically significant positive effects of viewing the welfare reform information.

This estimate is based on our Guesstimate model, which indicates that between 0.005 and 0.04 animals will be spared per meal. It is consistent with another estimate made independently by Mark Middleton of Animal Visuals; he calculated that FAPC’s work with schools and hospitals will spare about 685,000 animals from being used and killed (see our 2016 conversation with Paul Shapiro).

We ourselves have expressed this concern, such as in our report on corporate outreach, even though we believe overall that humane reform has a net benefit on the likelihood of further improvements for animals.

“Is it not just a little ironic that a representative of the Meat and Livestock Commission understands perfectly what is going on here? “Happy” meat makes “the whole thing look more acceptable.” “Happy” meat means more meat eaters and more slaughtered animals.”—Francione, G. (February 7, 2007). “Happy” Meat/Animal Products: A Step in the Right Direction or “An Easier Access Point Back” to Eating Animals? Animal Rights: The Abolitionist Approach.

“There is a clear trend that suggests Chipotle and McDonald’s are playing something close to a zero-sum game for customers. U.S. bar and restaurant sales grew just 2.9% in 2014, according to Technomic. After inflation, restaurants are fighting for a larger slice of a fixed pie.”—Cooper, T. (March 4, 2015). Why Chipotle Mexican Grill, Inc. Will Eat McDonald’s Corporation’s Lunch. The Motley Fool.

“Animal advocates give awards to slaughterhouse designers and publicly praise supermarket chains that sell supposed “humanely” raised and slaughtered corpses and other “happy” animal products. This approach does not lead people incrementally in the right direction. Rather, it gives them a reason to justify going backwards. It focuses on animal treatment rather than animal use and deludes people into thinking that welfare regulations are actually resulting in significant protection for animals.”—Francione, G. (February 7, 2007). “Happy” Meat/Animal Products: A Step in the Right Direction or “An Easier Access Point Back” to Eating Animals? Animal Rights: The Abolitionist Approach.

“While cage free eggs may be more humane than battery cage eggs, they are still far from ideal…Offering minor improvements for the way we treat farmed animals is a small step, however, it should not be misinterpreted as a win.”—Buff, E. (January 12, 2015). Why California’s New Animal Welfare Law is a HUGE Lesson for Animal Activists. One Green Planet.

Although most advocates agree that it is less bad for an animal to be raised for food with less suffering, some believe that the act of farming animals is intrinsically harmful and even if we reduced or eliminated suffering in animal agriculture, it would still be very bad. Gary Francione has made claims that seem to suggest this view, such as: “They are angry that I am what they call an “absolutist” who maintains that we cannot justify *any* animal use. They are right. I am an absolutist in this regard—just as I am an “absolutist” with respect to rape, child molestation, and other violations of fundamental human rights. Indeed, I would not have it any other way. Absolutism is the only morally acceptable response to the violation of fundamental rights whether of humans or nonhumans.”—Francione, G. (November 4, 2015). A Lot of People Are Angry with Me—And They Are Right. The Abolitionist Approach.

Cage-free systems might also cause or increase some welfare issues. For instance, in cage-free systems, “hens stir up dust while walking on the floor, which contains some of the birds’ manure, elevating ammonia levels.”—Kesmodel, D. (March 18, 2015). Cage-Free Hens Study Finds Little Difference in Egg Quality. Wall Street Journal.

“For example, thanks to Josh Balk’s [of Hampton Creek Foods] relationship with Compass Group, Compass Group has switched to Just Mayo for all their mayonnaise, which has removed an unbelievable number of eggs from the supply chain. Similarly, THL is campaigning for Shake Shack to sell veggie burgers at the moment. This kind of work would be very valuable: directly, for the animals involved, and indirectly, for the news coverage produced.”—Conversation with David Coman-Hidy (October 1, 2015).