HSUS Farm Animal Protection Campaign

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2018 |

Archived Version: November, 2018

What does HSUS Farm Animal Protection do?

The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) works on behalf of a large variety of animal causes, including but not limited to: companion animals, wild animals, animals used for entertainment, animals used in laboratories, and farmed animals. This is a review of their Farm Animal Protection team.

The two primary goals of the HSUS Farm Animal Protection (FAP) are (i) combating the most extreme confinement practices and abuses in the animal agribusiness system, and (ii) reducing total demand for animal products. They work with animal product producers to implement improvements in the treatment of animals used for food. They lobby for better laws, fight “ag-gag” legislation, and engage in campaigns to rid factory farms of the worst animal abuses. They sometimes conduct investigations of factory farms. FAP helps educational institutions, businesses, hospitals, the military, and correctional facilities to develop and implement meat, egg, and dairy reduction campaigns, and to increase plant-based options.

What are their strengths?

As HSUS is one of the largest and most recognized animal protection organizations in the United States, they are frequently covered in the media and thus able to reach very large numbers of people through their work. Additionally, HSUS FAP takes a strategic approach to implementing change. They recognize that large changes can’t always be achieved overnight, so they work to meet goals that are attainable as well as significant. They have a strong track record in legal work, corporate outreach, and institutional meat reduction programs. We believe their legal work is particularly effective, in part because they are one of the only groups doing this kind of work in the U.S.

What are their weaknesses?

FAP is part of HSUS, which came under public scrutiny in early 2018 for sexual harassment allegations and severe cultural problems, which were perpetuated by the charity’s leadership. HSUS’ Board of Directors, for example, initially chose to retain Pacelle as President and CEO despite the numerous allegations that were made against him by multiple named and unnamed women—allegations that had been vetted and reported by media sources such as The Washington Post and The New York Times. Eight Board Members have since resigned, seven of whom left in opposition to the initial decision to retain Pacelle. We are somewhat concerned that many of the remaining Board Members must have been among those who voted to retain Pacelle.

Another concern about donating to FAP is that it is difficult for us to ascertain exactly how much funding for FAP activities comes directly from their own budget rather than the general budget of HSUS. Since at least some of FAP’s costs (e.g. infrastructure costs) are covered by HSUS’ budget, it is difficult to ascertain how much money is actually being spent to achieve success with their efforts. It is also unclear whether donations that are not large enough to fund a program or position would be entirely fungible, or whether they would indeed be used in the FAP department as additional marginal funding.

HSUS Farm Animal Protection was a Standout Charity from May 2014 to February 2018.

Table of Contents

- How HSUS Farm Animal Protection Performs on our Criteria

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Supplementary Materials

How HSUS Farm Animal Protection Performs on our Criteria

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Before investigating the particular implementation of a charity’s programs, we consider their overall approach to animal advocacy in terms of the cause(s) they advance and the types of outcomes they achieve. In particular, we consider whether they’ve chosen to pursue approaches that seem likely to produce significant positive change for animals—both in the near and long term.

Cause Area

HSUS FAP focuses primarily on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we believe is a high-impact cause area.

Types of Outcomes Achieved

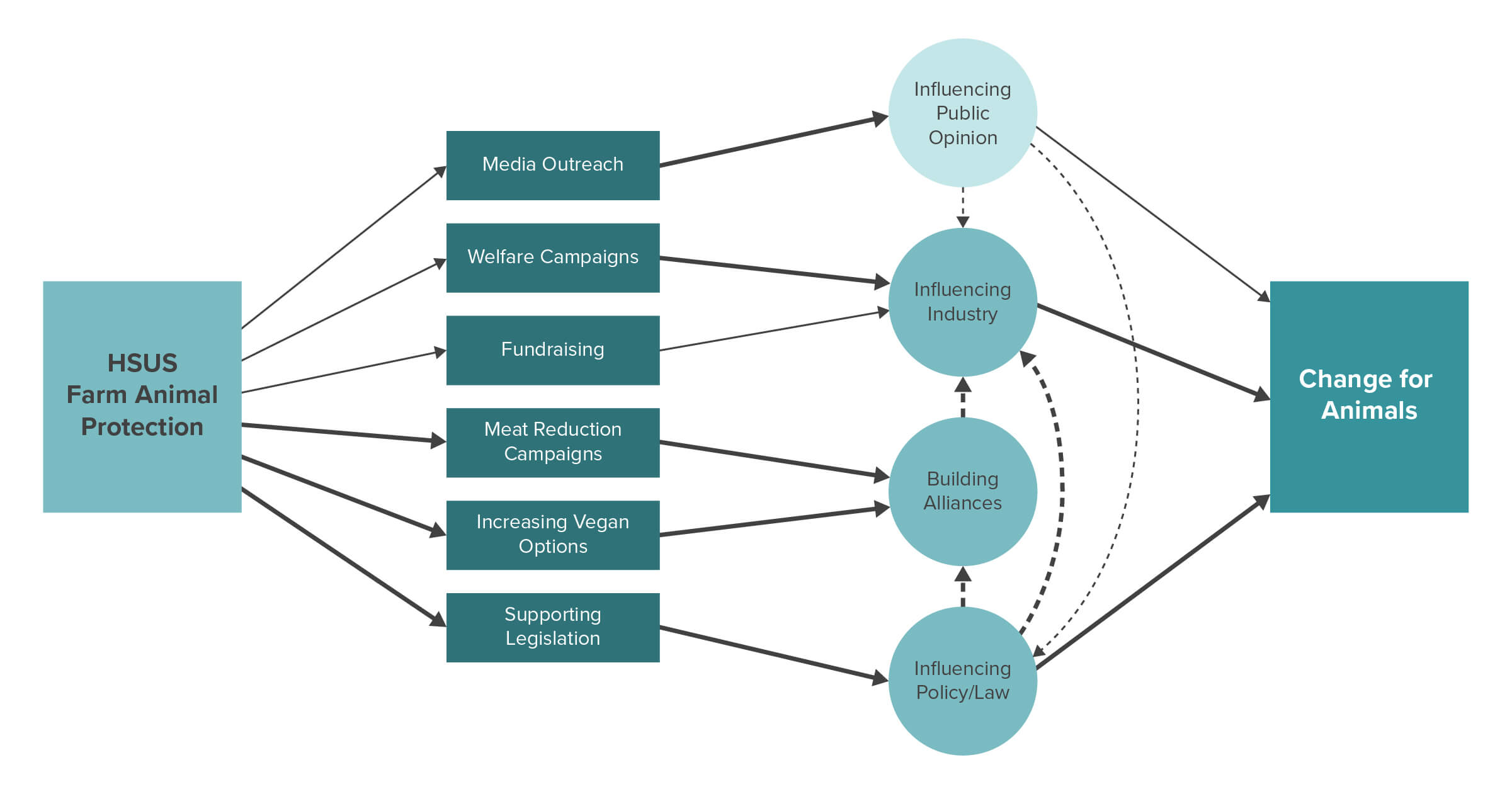

To better understand the potential impact of a charity’s programs, we’ve developed a menu of outcomes that describes five avenues for change: influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

HSUS FAP pursues many different avenues for creating change for animals: they work to influence public opinion, influence industry, build alliances, and influence policy and law. Pursuing multiple avenues for change allows a charity to better learn about which areas are more effective so that they will be in a better position to allocate more resources where they may be most impactful. However, we don’t think that charities that pursue multiple avenues for change are necessarily more impactful than charities that focus on one.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small and/or uncertain effects.

Influencing Public Opinion

HSUS FAP works to influence individuals to adopt more animal-friendly attitudes and behaviors through media outreach, which we view as an especially promising approach.1 While it is difficult to measure incremental changes in public opinion—and, consequently, difficult to know when an intervention is more or less successful—we still think it’s important for the animal advocacy movement to target some outreach toward individuals. This is because a shift in public attitudes and consumer preferences could help drive industry changes and lead to greater support for more animal-friendly policies. However, we find that efforts to influence public opinion seem much less neglected than other categories of interventions in the United States.2

HSUS FAP conducts media outreach by pitching stories, writing op-eds, and performing cooking demonstrations on TV.3 Using only approximately 2% of their budget in 2017,4 they reported being able to generate around 300 media pieces—many in mainstream media—in English and Spanish.5 Their frequent presence on widely-viewed television programs may expose a large and diverse set of people to plant-based eating and cooking. Some of the people encountering these programs might be relatively unlikely to encounter this kind of information in their personal lives.

Influencing Industry

HSUS FAP works with corporations to adopt better animal welfare policies and to ban particularly cruel practices in the animal agriculture industry. Though the long-term effects of corporate outreach are yet to be seen, we believe that these interventions have a high potential to be impactful when implemented thoughtfully.6

HSUS FAP conducts corporate outreach to convince large companies to make welfare commitments, including improvements for broiler chickens, commitments for cage-free eggs, and bans on fur.7, 8 HSUS FAP also works to help direct funding to support the development of plant-based and cultured meat,9 and they engage with industry leaders and corporations by speaking at shareholder meetings, hosting webinars, and attending conferences.10

Building Alliances

HSUS FAP’s work with restaurants, schools, hospitals, and other large organizations on institutional meat reduction provides an avenue for high-impact work, since it can involve convincing a few powerful people to make decisions that may influence the lives of millions of animals.11 Unless these key influencers are significantly more difficult to reach, this seems more efficient than general individual outreach because a great deal more individuals would need to be reached to create an equivalent amount of change.

HSUS FAP works with some of the world’s largest food service organizations, including Aramark, Sodexo, and Compass Group, to replace animal-based ingredients with plant-based ones at schools, hospitals, and in the military.12 Their work with these food service organizations has led to the introduction of more plant-based options on a large scale.13 Through their work with Aramark, there are now more plant-based options at Arizona State University, one of the largest universities in the United States.14 Through a collaboration with Compass Group, HSUS FAP has helped develop a plant-based restaurant concept, “Rooted,” that is designed to become a vegan section of dining halls.15 They also worked directly with schools and hospitals to increase plant-based offerings.16 One element of their meat reduction program about which we’re less confident of the marginal effectiveness is their chef training program.17 While chef training may be an important element to the ultimate success of restaurants, hospitals, schools, and the military, it is unclear how the marginal impact of this type of work may compare with others.

Influencing Policy and the Law

HSUS FAP works to encode animal welfare protections into law, which we think may be especially effective at creating change.18 We think that encoding protections for animals into the law is a key component in creating a society that is just and caring towards animals. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects to be particularly long-lasting.

Across the country, HSUS FAP has fought back against the animal agriculture industry’s attempts to introduce “ag-gag” bills, the King amendment, and other laws that could make welfare reforms more difficult.19 While some of these victories didn’t affect immediate positive change for animals, they did prevent changes in law that we think would have led to more suffering in the long term. Besides this defensive legal work, HSUS FAP has also worked to enact laws that add protections or ban particular farming practices. For example, they worked toward the recent passage of a law banning battery cages in Rhode Island as well as Proposition 12 in California, which will ban the confinement of calves, pigs, and hens in cages. It will also ban the sale of animal products from calves, pigs, and hens raised in cages.20 We think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to have an impact on a large number of animals, and are more likely to be followed through on than similar corporate campaigns.

Long-Term Impact

Though there is significant uncertainty regarding the impact of interventions in the long term, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.21 The potential number of individuals affected by a charity increases over time due to both human and animal population growth, as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Predictions about the long-term impact of any intervention are always extremely uncertain, because the effects of an intervention vary with context and are interdependent with concurrent interventions—with neither of these interactions being constant over time.22 When estimating the long-term impact of a charity’s actions, we consider the context in which they occur and how they fit into the overall movement. Barring any strong evidence to the contrary, we think the long-term impact of most animal advocacy interventions will be net positive. Still, the comparative effects of one intervention versus another are not well understood.23 Because of the difficulties in forecasting long-term impact, we do not put significant weight on our predictions.

Partly due to the scale on which it operates, HSUS FAP has the potential to make a large difference—their media outreach targets a wide and international audience, and their institutional outreach programs alter large-scale purchases. The long-term impact of some of their work, such as getting corporations to commit to welfare reforms in the future, remains to be seen since we don’t know how well corporations will comply, how much work enforcement will take, or how public opinion will be affected.

We’re generally optimistic that obtaining corporate welfare commitments will (i) lead to improvements in welfare in the long term,24 (ii) reduce consumption of animal products via price increases,25 and (iii) may raise awareness of the terrible welfare conditions on factory farms.26 However, some evidence suggests that welfare will not be significantly improved in cage-free systems, and that in some ways the conditions for hens may be worse, particularly in the transition from caged systems to cage-free systems.27, 28 Some animal advocates worry that marketing eggs and other animal products as “humane” may obscure the suffering and exploitation these purchases support. For some consumers, this may contribute to a belief that animals aren’t harmed in the production of “humane” products, which, some argue, could make subsequent efforts to reduce consumption of animal products more challenging.29, 30 HSUS FAP’s other institutional outreach programs that aim to displace animal products in the food service industry with vegan products avoid the risk of these potential negative outcomes.

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

In order to recommend a charity, we need to assess the extent to which they will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. Specifically, we need to consider whether there may be non-monetary “bottlenecks,” or barriers to the charity’s growth. First, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. Next, we evaluate the charity’s room for more funding by considering existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential new programs and areas for growth. It is important to determine whether any barriers limiting progress in these areas are solely monetary, or whether there are other inhibiting factors—such as time or talent shortages. Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for more funding sooner than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we have suggested. Our estimates are intended to indicate the point at which we would want to check in with a charity to ensure that they have used the funds they have received effectively and are still able to absorb additional funding.

Recent Financial History

HSUS FAP has maintained a fairly steady amount of revenue and expenses for the last few years. They report that this year there is some uncertainty as to how the California ballot measure they led will impact their funding—some donors who might have donated directly to HSUS FAP may have chosen to support this legislation instead.31

The chart below shows HSUS FAP’s recent revenues and expenditures.32

Planned Future Expenses

Following the passing of Proposition 12 in California, HSUS FAP plans to invest significant resources into passing similar laws across the country.33 Outside of their legislative work, they plan to continue with their corporate campaigns for (i) welfare reforms for chickens farmed for meat and (ii) increasing the availability of plant-based options.34 They also report planning to collaborate with and help animal charities around the world, assisting them to work with food service companies to increase plant-based offerings.

Assessing Funding Priority of Future Expenses

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area will likely vary in its potential cost effectiveness. In addition to evaluating a charity’s planned future expenses, we consider the potential impact and relative cost effectiveness of filling different funding gaps. This helps us evaluate whether the marginal cost effectiveness of donating to a charity would differ from the charity’s average cost effectiveness from the past year. We break down the total room for more funding into three priority levels, as follows:

High Priority Funding Gaps

Our highest priority is funding activities or programs that we think are likely to create longer-term impact in a cost-effective way, as well as programs which we have relatively strong reasons to believe will have a highly positive short- or medium-term direct impact in a cost-effective way.35

As described in Criterion 1, HSUS FAP has a number of programs that we consider promising, including their meat reduction campaigns, welfare campaigns, media outreach, and legislative work. Of these programs, we estimate they could effectively use the largest increases in funding for their meat reduction campaigns36 and their welfare campaigns.37 We estimate that HSUS FAP has a high priority funding gap of $520,000–$1.6 million for 2019.38, 39, 40

Moderate Priority Funding Gaps

It is of moderate priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively moderate marginal cost effectiveness.

Considering their chef trainings program,41 we estimate that HSUS FAP has a moderate priority funding gap of $50,000–$340,000 for 2019.42

Low Priority Funding Gaps

It is of low priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively lower marginal cost effectiveness, or to replenish cash reserves. Because it is likely that there may be future expenditures we haven’t thought of, we also include in this category an estimate of possible additional expenditures (based on a percentage of the charity’s current yearly budget).

Using a range estimate of 1%–20% of their projected 2018 expenses to account for possible additional expenditures, we estimate that HSUS FAP has a low priority funding gap of $30,000–$790,000 for 2019.43

The chart below shows the distribution of HSUS FAP’s gaps in funding among the three priorities: 44

HSUS FAP estimates that they could effectively use an additional $2 million over their current budget to work more on plant-based meats and an almost unlimited amount on ballot measures banning cruel farming practices.45 We estimate that next year they have a total funding gap of approximately $40,000–$2.5 million,46 and that they could effectively put to use a total revenue of $4.4–$6.1 million. All things considered, we only recommend making restricted donations to HSUS FAP in larger amounts, i.e., large enough to fund a new employee position (approximately $50,000) or a specific campaign (anywhere from $10,000 to $10 million), especially as we are unsure to what extent funds donated to HSUS FAP more generally are fungible with general HSUS funds. If you are considering a donation to the HSUS FAP, we encourage you to restrict your donation to the FAP, or even more specifically to a particular program. We also recommend contacting Josh Balk to discuss specifics.

Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

HSUS FAP runs several programs; we estimate cost effectiveness separately for a number of these programs, and then combine our estimates to give a composite estimate of HSUS FAP’s overall cost effectiveness.47 We generally present our estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. We think that this quantitative perspective is a useful component of our overall evaluation because we find quantitative models of cost effectiveness to be:

- One of the best methods we know for identifying cost-effective interventions48

- Useful for making direct comparisons between different charities or different interventions49

- Useful for providing a foundation for more informative cost-effectiveness models in the future

- Helpful for increasing our transparency50

That said, the estimates of equivalent animals spared per dollar should not be taken as our overall opinion of the charity’s effectiveness. We do not account for some programs that have less quantifiable kinds of impact in this section, leaving them for our qualitative evaluation. For programs that we do include in our quantitative models, our cost-effectiveness estimates are highly uncertain approximations of some of their short-term costs and short- to medium-term benefits. As we have excluded more indirect or long-term impacts, we may underestimate the overall impact. There is a very limited amount of evidence pertaining to the effects of many common animal advocacy interventions, which means that in some cases we have mainly used our judgment to assign quantitative values to parameters.

We are concerned that readers may think we have a higher degree of confidence in this cost-effectiveness estimate than we actually do. To be clear, this is a very tentative cost-effectiveness estimate. It plays only a limited role in our overall evaluation of which charities and interventions are most effective.51

Institutional Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 HSUS FAP will spend about 44% of their budget, or $1.7 million, on institutional outreach.52 This will result in some institutions adopting new policies, and these policies will likely result in reduced suffering for animals. We estimate that HSUS FAP’s institutional outreach will help cause 40–80 policies to be changed, and 1,800–3,200 chefs to be trained.53

Corporate Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 HSUS FAP will spend about 41% of their budget, or $1.5 million, on corporate outreach.54 This will result in some companies adopting new policies, and these policies will likely result in reduced suffering for animals. We estimate that HSUS FAP’s corporate campaigns will help cause 27–48 policy changes affecting 11–260 million broiler chickens.55

Legislative Advocacy

We estimate that in 2018 HSUS FAP will spend about 13% of their budget, or $500,000, on legislative advocacy.56

Media Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 HSUS FAP will spend about 1% of their budget, or $50,000, on media outreach.57 This will lead to HSUS FAP being featured in 300–620 articles at a cost of $90–$180 per article.58

Budget Changes Since 2017

The following chart shows the ways in which HSUS FAP’s budget size and allocation has changed since 2017.

All Activities Combined

To combine these estimates into one overall cost-effectiveness estimate, we translate them into comparable units. This introduces several possible sources of error and imprecision. The resulting estimate should not be taken literally—it is a rough estimate, and not a precise calculation of cost effectiveness.59 However, it still provides some useful information about whether HSUS FAP’s efforts are comparable in cost effectiveness to other charities’.60

We consider multiple factors61 to estimate that HSUS FAP spares an equivalent of between 0.3 and 35 animals per dollar spent on institutional outreach.62

We consider multiple factors63 to estimate that HSUS FAP spares an equivalent of between -10 and 30 animals per dollar spent on corporate outreach.64, 65 We exclude their work on fur farms due to our large uncertainty about the number of animals affected.

We also exclude legislative advocacy and media results from our final cost-effectiveness estimates and don’t attempt to convert them into an equivalent animals spared figure; it is too difficult to disentangle the effects of these interventions from the total effects of their other programs.

We weight our estimates by the proportion of funding HSUS FAP spends on each activity; overall, we estimate that in the short term—after excluding the effects of some of their programs—HSUS FAP spares between -5 and 13.5 farmed animals per dollar spent.66, 67 This equates to between -0.4 and 4 years of farmed animal life spared68 per dollar spent.69, 70, 71 Because of extreme uncertainty about even the strongest parts of our calculations, we feel that there is currently limited value in discussing these estimates further. Instead, we give weight to our other criteria.

Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

To evaluate a charity’s track record, we consider how well the charity has executed previous programs. We also consider the extent to which these previous programs caused positive changes for animals. Information about a charity’s track record helps us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments—information that cannot always be incorporated into the criteria above. An organization’s track record can be a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences in other important factors.

Have programs been well executed?

Notable achievements since FAP’s founding in 2005 include leading successful legal campaigns to ban inhumane practices, encouraging companies to eliminate gestation crates and battery cages, mobilizing investments in plant-based foods, and convincing institutions—including many school districts—to implement meat reduction policies like Meatless Mondays.

For years, FAP has worked to generate institutional meat reduction policies.72 They report that this has resulted in hundreds of policies, and they estimate that hundreds of millions of meals containing meat were replaced with meatless ones.73 FAP reports they have formed multi-year relationships with some of the world’s largest food providers (e.g., Compass Group) to offer support for chef trainings and menu development. Through their chef trainings, FAP has now reached thousands of chefs over the years.74

Their extensive work in their plant-based division seems to be progressing well—they’ve seen improvement in the scale and influence of some of their latest corporate partners relative to previous years.75 For example, their new partner Compass Group has 100 times more client accounts than Creative Dining, one of the largest food service companies they’ve partnered with in the past year.76 Another food service company that they have worked with extensively this year is Aramark, which has an account with Arizona State University (ASU), the largest university in the United States. FAP tells us that about 80,000 people purchase food on the ASU campus per day—80,000 people who are now exposed to new plant-based options.77 FAP reported that they ask these food service companies to review how much meat they served before and after the introduction of their plant-based products.78 Prior to FAP’s work with Aramark, FAP claimed that the amount of meat ASU was serving was actually increasing, likely due to the growing student body and the corresponding rise in demand for meat products. After FAP partnered with Aramark, the reported amount of meat purchased at ASU has decreased.79 If accurate, this suggests that the reported meat reduction at ASU may be evidence of FAP’s programs’ significant influence.

FAP works to prevent “ag-gag” bills from becoming laws; they have led successful efforts to stop more than 30 of such bills.80 Without their work on this front, it would be much more difficult for FAP and other charities to conduct undercover investigations in the United States. FAP also led the campaign in passing and subsequently defending California’s Proposition 2 measure that prohibits the confinement of farmed animals in a manner that does not allow them to turn around freely, lie down, stand up, or fully extend their limbs.81, 82 FAP also played an important role in Question 3, a successful ballot measure in Massachusetts that prohibits confining pigs, veal calves, and egg-laying hens in a way that prevents the animal from lying down, standing up, fully extending its limbs, or turning around freely (with some exceptions).83 It also prohibits the sale of products from animals confined in this way, regardless of where they were raised (with some exceptions).

HSUS FAP’s involvement in the California Proposition 2 ballot initiative helped them to secure cage-free commitments from major corporations. For example, it led to McDonald’s 2015 announcement, which preceded a series of similar commitments from other companies.84 More recently, FAP has switched their focus from improving the conditions for laying hens to improving the conditions for broiler chickens, and they report numerous successes on that front.85 Their corporate outreach work has also included fur-free policies.86

While FAP focuses primarily on influencing corporate and public policy rather than individual attitudes, they have also had some success in the creation and promotion of educational videos. For example, their 2016 video titled “Free chicken in NYC!” has been viewed approximately 700,000 times on HSUS’ Facebook page, and another approximately 640,000 times after the video was picked up by Upworthy. Their anti-gestation crate video has been viewed approximately 1.5 million times on Youtube.

Have programs led to change for animals?

We believe FAP bears a large portion of the responsibility for securing cage-free commitments that could affect the lives of millions of hens living in factory farms. For example, they helped pass Proposition 2 in 2008, which bans battery cages, gestation crates, and veal crates in California. Similarly, the passing of Proposition 12 in November 2018 will also lead to considerable change for animals.87 The commitments made due to FAP’s corporate outreach campaigns will likely affect a large number of animals if they are implemented. As these commitments are not legally binding, it will be especially important to follow up with companies to ensure they are adhered to. Since several of the commitments obtained by FAP have deadlines in the early to mid 2020s, we may soon have a better understanding of how many companies meet their deadlines. FAP estimates that their corporate policy victories will reduce the suffering of millions of animals per year once they have been implemented.88

FAP reports that the meat reduction policies they worked to implement in schools in 2012–2017 will result in 399 million meat-containing meals being replaced by meatless meals.89 This change will reduce the demand for animal products—we estimate that it will spare between 12 and 15 million farmed animals from being raised and killed in factory farms.90

FAP’s work to prevent “ag-gag” bills has potentially led to change for animals by making it easier for charities to conduct undercover investigations in the United States. The impact of investigations of difficult to track in the short term, but we think they are potentially highly effective. Additionally, FAP is very good at getting media coverage of their activities.91 There is weak evidence that media coverage of the treatment of farmed animals is negatively correlated with meat consumption in the United States;92 if such a correlation exists, it is possible that such coverage nudges people towards reduction in meat consumption.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

A charity that has systems in place for assessing their programs is better equipped to move towards their goals effectively. By conducting self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs, and modify or end those that are less successful. When such systems of improvement work well, many stakeholders benefit: benefactors are inclined to be more trusting and more generous, leadership is able to refine their strategy for achieving their goals, and nonhuman animals benefit more.

To evaluate how well the charity adapts to successes and failures, we consider: (i) how the charity has assessed its past programs and (ii) the extent to which the charity updates their programs in light of those assessments.

Does the charity actively assess areas of success and failure?

HSUS FAP measures the immediate impact of their programs when possible. For example, they report tracking the effects of their corporate reform victories and the amount of meat reduction caused by their Meatless Monday program in order to estimate the number of animals spared.93 We agree that it is generally easier for organizations to measure their impact on animals when influencing corporate, public, or institutional policy rather than individual behavior. That being said, we don’t necessarily recommend that charities focus on producing only easily measurable outcomes. In the case of HSUS FAP in particular, they seem to measure their success by assessing the tangible effects that they have on animals via their institutional efforts to reduce meat consumption, improve welfare standards, or both. They also seem to measure their success by considering the size of the companies they target.94

HSUS FAP tracks the litigation they help to pass,95 the media attention they generate,96 and the corporate commitments they secure.97 Outside of these domains, they don’t appear to measure their progress in a formal manner. They don’t yet have a formal strategic plan, and we are concerned that they do not formally set clear, SMART goals.98 HSUS FAP suggests that their lack of goals for the coming year is due in part to the fact that many of their goals and long-term plans—particularly in the legislative division—were to be determined by the outcome of Proposition 12 in California in late 2018, which they went on to successfully achieve.99

They report that two-thirds of their staff work in their plant-based division,100 so we believe that a substantial portion of their goals involve efforts to popularize plant-based diets. They tell us that they are looking to expand the work of their plant-based division further around the United States and to provide support globally as well. To that end, they have partnered up with ProVeg International in Germany on an event to teach organizations around the world how to do the work that they’re currently doing in the United States (i.e., bringing plant-based options into food service companies).101 In 2016, HSUS FAP streamlined their meat reduction strategy by implementing Forward Food (initially named “Food Forward”) which brought together dozens of dining and purchasing Directors for plant-based trainings.102 In 2013, they created one-day symposia so that food service professionals can learn from industry leaders and peers about meeting the demand for plant-based meals and marketing healthy foods.103 They hosted seven such symposia, labeled “Forward Food Leadership Summits,” at various locations in the U.S. and Canada, attracting more than 400 attendees.104 In 2018, “Forward Food” culinary trainings expanded to more countries. HSUS FAP considers this program to be highly successful, in part because of the effects that it has inspired. For instance, the University of Pittsburgh’s dining team created a fully plant-based station called “Forward Food” after participating in HSUS’ program.105 This chronology of events suggests that HSUS FAP has put some effort into tracking and refining these meat reduction initiatives. Nonetheless, we believe FAP would benefit from a formal system of assessing the impact that their food service training programs have on relevant factors, like the estimated number of animals affected. We also believe FAP could benefit from evaluating the relative results of their programs to try to learn about what makes them successful and how they can be further improved.

FAP’s reports on their extensive work with dining services suggest some attempt to assess the number of consumers that are being exposed to plant-based options.106 To some degree, they also suggest an attempt to assess the reduction in meat consumption resulting from their efforts,107 although they’ve said that measuring effectiveness in this domain is complicated.108

Does the charity respond appropriately to areas of success and failure?

HSUS FAP has demonstrated willingness to innovate and to refine their programs throughout the years. Their recent focus on plant-based food service advocacy indicates that HSUS FAP can respond well to new opportunities to substantially expand their work into promising areas, despite the fact that they are an older organization with established traditions.109 Another example of them being open to exploring new opportunities is in their plans for future legislative work regarding broiler chickens.110

They have also shown that they can respond well to challenges. For example, their legislative division recently passed a historic law in Rhode Island to ban the confinement of egg-laying hens in cages.111 Since there was no ballot measure, they had to work through the legislature. Relatedly, they also appear to have changed course when their strategies were not working as planned. For example, when waging their legislative campaigns, they reportedly started using more effective means of promotion.112

In addition to meeting challenges, HSUS FAP has demonstrated that they can recognize and capitalize on their existing strengths. For instance, one strength they appear to have capitalized on is their legislative work. In every ballot measure that they contribute to, they reportedly try to strengthen the legislative language relative to their previous work; to do this, they use a data-driven approach to determine what kind of language will be most effective.113 That approach consists of collecting in-depth polling information to determine how to make their language strict enough to be effective while also resonating with the average voter. So far, they have successfully led every ballot measure they have worked on, which seems like a good indicator that their process is effective.114

While we believe that FAP’s leadership is research-oriented,115 we think FAP could put more effort into tracking and improving both their programmatic effectiveness and their organizational effectiveness more formally. With regard to the latter, it might be particularly helpful for HSUS to evaluate their progress on organizational factors relating to their board and their administration.

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

A charity is most likely to be effective if it has a well-developed strategic vision and strong leadership who can implement that vision. Given ACE’s commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we generally look for charities whose direction and strategic vision are aligned with that goal. A well-developed strategic vision must be realistic to manage and execute. It is likely the result of well-run, formal strategic planning; when a charity’s leaders regularly engage in a reflective strategic planning process, revisions and improvements to the charity’s strategic vision are likely to follow.

Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-composed board?

FAP is unique among the organizations we review in that they are one department of a large organization; they are supported by the leadership, overarching strategy, and resources of the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS). This has potential benefits and costs: FAP can utilize HSUS’ name recognition and membership base for its campaigns, but the structure could also make coordination difficult and increase bureaucratic inefficiency.

In the past year, HSUS faced some very public controversy regarding its leadership and board. A number of sexual harassment allegations came to light regarding former CEO Wayne Pacelle, as well as former Vice President of Policy Paul Shapiro (who was previously Vice President of Farm Animal Protection). While both Pacelle and Shapiro have now left HSUS, we are concerned that some elements of HSUS’ leadership and some of the systems and structures that allowed a culture of harassment to persist for so long may still be in place.

One structure that evidently enabled HSUS’ culture of harassment, at least until earlier this year, was its Board of Directors. In February 2018, the board initially chose to retain Pacelle as President and CEO despite the numerous allegations that were made against him by multiple named and unnamed women—allegations that had been vetted and reported by media sources such as The Washington Post and The New York Times. Seven of HSUS’ then 31 Board Members resigned in protest of the board’s decision, and Pacelle resigned the following day after donors and employees began to distance themselves from the organization. Shortly thereafter, HSUS also announced the resignation of Board Member Erika Brunson, one of Pacelle’s most vocal supporters in the press. HSUS now appears to have appointed three new Board Members, and let one go, for a total of 24 members. We are unsure of the remaining Board Members’ positions on harassment or the importance of listening to and supporting all staff. However, we feel there is some cause for concern given that seven Board Members resigned in protest of Pacelle’s behavior. Since the Board Members who voted to retain Pacelle were presumably not among the group that resigned, it seems likely that the board may now have a relatively larger proportion of members who wanted to keep a leader in place in light of concerning evidence of harassment. While we don’t know how many Board Members who opposed the decision to retain Pacelle remain on the board, or how this process may have affected the views of those who did remain, we are concerned that if a similar incident were to occur again, there may now be a relatively larger proportion of Board Members who, in this instance, voted to retain a leader despite serious evidence of harassment.

Aside from our concerns regarding the attitudes of some Board Members, the size and occupational diversity of HSUS’ board is in line with U.S. best practices.116, 117

Does the charity have a well-developed strategic vision?

Does the charity regularly engage in a strategic planning process?

HSUS FAP does not currently have a formal strategic plan. They tell us they will develop one at the end of 2018.118 Major decisions—like the decision to start new programs or to launch ballot measures—require approval from HSUS’ Board of Directors. FAP tells us that, thus far, the board has been highly agreeable to new proposals, like the development of FAP’s Food and Nutrition Division. The board has also approved all of FAP’s ballot measure projects.119

Does the charity have a realistic strategic vision that emphasizes effectively reducing suffering?

We currently consider helping farmed animals to be the most promising cause area to support, all else being equal. We are therefore more excited about the work of FAP relative to other HSUS programs. We understand that HSUS as an organization takes a more mainstream approach, helping people connect more obvious forms of cruelty, such as a dog left on a chain without food and water, with less obvious forms that affect many more animals, such as the confinement of farmed animals. All things considered, we think HSUS should expand its farmed animal program, but not necessarily shift all of its resources towards that area.

Does the charity’s strategy support the growth of the animal advocacy movement as a whole?

It’s our view that HSUS FAP fills a niche in the animal advocacy movement because they currently invest more heavily than any other animal charity in legislative work in the U.S.120 HSUS FAP also collaborates with other animal charities on some campaigns to improve animal welfare.121

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Effective charities are generally well-managed on an operational level; they should have healthy cultures and sustainable structures. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about their human resources policies and their perceptions of staff morale. We also speak confidentially with non-leadership staff or volunteers at each charity to solicit their perspectives on the charity’s management and culture.122 Finally, we send each charity a culture survey and request that they distribute it among their team on our behalf.123, 124

Does the charity have a healthy culture?

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly towards all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. One important part of acting responsibly towards stakeholders is protecting employees from instances of harassment and discrimination in the workplace. Charities that have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, since varied points of view improve a charity’s ability to respond to new situations.125 A healthy charity is transparent with donors, staff, and the general public and acts with integrity; in other words, their professed values align with their actions.

FAP is part of HSUS, which came under public scrutiny in early 2018 for sexual harassment allegations and severe cultural problems, which persisted for many years and were perpetuated by the charity’s leadership. We wrote about the allegations on our blog, and we decided to rescind our previous recommendation of HSUS FAP as a Standout Charity.

Roughly six months later, HSUS’ farm animal protection team tells us that their department is taking some positive steps to improve its culture. HSUS recently announced that they are undertaking a reconciliation process to improve workplace culture. Some HSUS FAP staff told us that they are hopeful about the future, and that they don’t believe the behavior of HSUS’ previous CEO and vice President of policy reflects the culture of the current FAP team. However, we think it may take significantly more time and effort for HSUS leadership to fully realize a safer workplace and regain the trust of their employees and other stakeholders.

Does the charity communicate transparently and act with integrity?

Because FAP is not an independent organization, but part of HSUS, we have less information about the transparency of their finances. HSUS FAP reports that all program expenditures are from dedicated FAP funds, but some infrastructure costs (e.g. funds for office space) come out of more general HSUS budgets. It may be legitimately difficult for FAP to know the total amounts of resources they use because of this funding structure.

We received mixed reports about the transparency and integrity of HSUS FAP’s internal culture. Some staff report that, in the wake of HSUS’ controversy, the organization is working on transparency and beginning to gain trust back from its employees. Other FAP staff report that the HSUS’ internal culture is “splintered.” In other words, there seems to be a lack of transparent communication, particularly between different departments. Some employees mentioned that the organization struggles with holding people accountable for mistakes. Most FAP employees seemed satisfied that their ideas and contributions are valued. However, more than one person mentioned that it can still be difficult for quieter individuals to make themselves heard.

Does the charity provide staff and volunteers with sufficient benefits and opportunities for development?

HSUS FAP staff were fairly split about the adequacy of their compensation. Many mentioned that, while their salaries may be comparable with those of other nonprofits, HSUS is located in an area with a high cost of living. However, the respondents to our culture survey generally felt quite positively about HSUS’ paid time off and health benefits.

FAP offers some opportunities for professional development; staff told us about trainings in management, giving presentations, implicit bias, and emotional intelligence. FAP reports that staff have access to Skillport, a library of online resources to assist with professional development, as well as reimbursement for other education that aligns with their roles.126 They also seem particularly focused on providing management training, which they do through an external professional development form called RedShift.127

One source of frustration among staff is HSUS’ system for providing direct feedback and evaluations to individual employees. Multiple people independently described this system to us as “outdated.”

Does the charity have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion?

Like many animal charities, HSUS FAP struggles to recruit a diverse staff. When we asked HSUS leadership how they promote diversity and inclusion through their hiring process, they noted that the vast majority of their team are women.128 (Of course, the majority of animal advocates are women.) We are more interested in whether HSUS is inclusive of all marginalized communities, and whether members of these communities (particularly women and people of color) are represented in the organization’s leadership. This was a source of concern for some respondents to our culture survey.

Does the charity work to protect employees from harassment and discrimination in the workplace?

Sexual harassment has been a serious and public problem within HSUS. In the past year, a number of sexual harassment allegations came to light regarding both CEO Wayne Pacelle and Vice President of Policy Paul Shapiro (formerly Vice President of Farm Animal Protection). These allegations were made by multiple women and reported by media sources such as The Washington Post and The New York Times. Still, after many of these allegations were made public, HSUS’ Board of Directors decided to retain Pacelle in what we considered to be a dramatic failure to protect the organization’s employees.

The general consensus among respondents to our recent survey is that, despite having experienced clear problems in the past, HSUS FAP’s culture is improving with regard to harassment. According to our survey, most HSUS FAP staff feel that they have someone (or multiple people) to whom they can report problems at work. Many told us that they are comfortable approaching their direct supervisors as well as the human resources department. Still, several staff members report that, while they are comfortable raising concerns about their work culture, they lack confidence that their concerns would be satisfactorily addressed. Despite the hopeful attitudes of HSUS FAP’s staff, we remain uncertain of the safety of HSUS as a workplace. We expect that it will take HSUS much longer than a few months to develop and implement policies that will effectively protect staff from the problems that have pervaded their culture for many years.

Does the charity have a sustainable structure?

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in which current leadership might move on to other projects. The charity should seem unlikely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, they should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

Does the charity receive support from multiple and varied funding sources?

It is difficult for us to determine precisely where the funding for FAP comes from, since it is part of a much larger organization. However, we feel confident that HSUS as a whole is financially sustainable.

Does the charity seem likely to survive potential changes in leadership?

HSUS has recently undergone multiple leadership changes. In 2016, Josh Balk replaced Paul Shapiro as the vice President of Farm Animal Protection. In 2018, Wayne Pacelle resigned as the CEO of HSUS and Kitty Block stepped in as the acting President and CEO. We believe that HSUS is well-established enough—financially and operationally—to withstand further leadership changes, if necessary.

;Revenue;Assets;Expenses; 2016;$3,550,000;$300,000;$3,250,000; 2017;$4,000,000;$634,065;$3,665,935; 2018 (estimated);$3,800,000;$692,386;$3,742,679; 2019 (estimated);$4,000,000;$1,091,386;$3,600,000;

,Lower estimate,Upper estimate High Priority,520000,1080000 Moderate Priority,50000,290000 Low Priority,30000,760000

;2017;2018; Legislative Work;$487,100;$499,928; Institutional Outreach;$1,617,600;$1,658,934; Media;$56,341;$54,700; Corporate Outreach;$1,506,535;$1,527,476;

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

For more information, see our recent research on the Allocation of Movement Resources.

“A key component of our campaign is putting animal welfare and plant-based eating in the spotlight by

pitching stories about to news media, writing op-eds, hosting cooking demonstrations on TV and sharing

our institutional partners’ success which makes animal welfare and plant-based eating more mainstream

to the general public and the food industry.” —HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 OverviewIn 2017, they spent about $55,000 on media-related salaries and an additional $15,000 on telecommunications. This information can be found in HSUS FAP’s Budget (2017–2018).

A full list of their 2017 media hits can be found in Appendix C of HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview.

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

Examples of companies that HSUS FAP has targeted with campaigns and which have now made welfare commitments include Burger King, Chipotle, Unilever, Aramark, Subway, General Mills, Carnival Cruise Lines, Nestle, KraftHeinz, among others. This information can be found in HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview.

HSUS FAP reports having worked with close to 100 companies on welfare reforms in the past year. This information can be found in our Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018).

While we were unable to verify this figure, HSUS FAP reports having contributed to directing around $200 million to startups working with plant-based and cultured meat. This information can be found in our Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018).

This information can be found in HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview.

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

“This year, we announced the most in-depth plant-based policies in the history of our movement. We developed these policies with three of the world’s largest food service companies: Compass Group, Aramark, and Sodexo.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

HSUS FAP estimates that their Meatless Monday Campaign has resulted in 399 million meals being replaced by meatless meals and 10.3 million animal saved between 2012 and 2017. This information can be found in HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview.

“As one example with Aramark, it has an account with Arizona State University (ASU), the largest university in the United States. In just one day, about 80,000 people purchase food on the ASU campus, and they will now be exposed to our new plant-based menu items and their dining staff will have in-depth plant-based culinary training options.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

“[W]e created a very similar plant-based dining concept with Compass Group called “Rooted.” This is a section of an existing dining hall which will now become entirely plant-based. Here at FAP, we created the concept, developed the menu, organized the recipes, and came up with the named “Rooted.” When we pitched it to Compass Group, they were very responsive and they’ve been launching it at numerous accounts ever since.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

This information can be found in HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview.

“In 2017, we conducted 80 hands-on culinary training with hundreds of schools, hospitals, universities, and even branches of the U.S. military, training more than 2,000 chefs and foodservice professionals how to cook delicious, hearty animal-free meals.” —HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

In 2017, HSUS fought legislation that would have granted legal protections and special privileges for industries engaged in animal cruelty in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Maine, California, Missouri, and Indiana as well as at the national level in their work against the King Amendment. This information can be found in HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview.

“The success of Proposition 12 would ban not only the confinement of calves, pigs, and hens in cages, but also the sale of eggs, pork, and veal from caged animals. This would mean that regardless of where an animal product is produced it cannot be legally sold in California if it was produced by an animal confined in a veal crate, gestation crate, or hen cage.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

See the 80,000 Hours article “Presenting the Long-Term Value Thesis” for a more detailed discussion of why long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.

“When outcomes of interventions are interdependent, the effectiveness of each is inextricably linked with those of the others. Justifying one as being more effective than another is not quite straightforward—declaring so is often misleading.” —Sethu, H. (2018) How ranking of advocacy strategies can mislead. Humane League Labs.

See ACE’s report on leafleting for a more detailed consideration of the potential long-term impact of a particular intervention.

Hens in a cage-free environment may have opportunities for behaviors that seem likely to improve their welfare such as dust bathing, perching, foraging, and nesting, which are not available in battery cages. For a description of some of these potential welfare improvements, see the Open Philanthropy Project’s report titled “How Will Hen Welfare be Impacted by the Transition to Cage-Free Housing?”

Cage-free eggs are currently more expensive than conventional eggs and some research suggests this is attributable to increased labor, feed, and pullet costs.

See, for example:

– Animal Charity Evaluators. (2016). Models of Media Influence on Demand for Animal Products. Animal Charity Evaluators. – Tiplady, C. M., Walsh, D. B., & Phillips, C. J. C. (2013). Public Response to Media Coverage of Animal Cruelty. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 26(4), 869–885.

– Tonsor, G. T., & Olynk N. J. (2010). Impacts of Animal Well-Being and Welfare Media on Meat Demand. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 62(1), 59–72.Several studies suggest higher levels of mortality in cage-free systems compared to battery cages, and there is reason to believe that higher levels of mortality correspond to lower levels of welfare since the increased mortality may result from disease, feather pecking, and injuries. Among the nine experts interviewed in The Open Philanthropy Project’s report, “How Will Hen Welfare be Impacted by the Transition to Cage-Free Housing?” there was unanimous agreement that mortality will likely be significantly higher following the transition to cage-free systems. Most experts agreed that mortality rates are higher in cage-free systems, even years after the transition. The authors of the report express optimism that producers will be motivated to—and capable of—reducing mortality levels to be comparable with battery cage systems, and they maintain the view that cage-free systems will have a net positive impact on welfare in the long term.

Some evidence suggests that, in addition to increased mortality, there are other negative impacts on chicken welfare in cage-free systems that may outweigh the improvements in behavioral opportunities, such as increased stress and worse air quality. See Direct Action Everywhere’s blog post suggesting that cage-free systems may not be better for chicken welfare than caged systems.

“‘Happy meat’ discourses […] invite ‘consumers’ to adopt a position of vicarious carer for the ‘farmed’ animals who they eat. […] While ‘animal-centred’ welfare reform and ‘happy meat’ discourses promise

a possibility of a somewhat less degraded life for some ‘farmed’ animals, they do so by perpetuating exploitation and oppression and entrenching speciesist privilege by making it less vulnerable to critical scrutiny.” —Cole, M. (2011). From “Animal Machines” to “Happy Meat”? Foucault’s Ideas of Disciplinary and Pastoral Power Applied to ‘Animal-Centred’ Welfare Discourse. Animals, 2011, 1, 83–101.For more information, see Sentience Institute’s list of arguments supporting and refuting the theory that welfare reforms will lead to complacency.

“Because a nonprofit can’t take the lead in raising funds for a political campaign, we had to create a separate entity known as Prevent Cruelty California, and this is where all donations to the ballot measure are directed. We just recently received a $1 million donation to the ballot measure, which would have otherwise gone to our team.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

Expenses for 2016 are from a 2016 private communication with HSUS FAP; revenue for 2016 is estimated using the provided expenses for 2016 and the ratio of revenues to expenses for 2017; expenses for 2017 and 2018 are from HSUS FAP Budget (2017–2018); revenue for 2017 is based on our Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018); revenue for 2018 is estimated to be similar to but not exceed expenses by as much as in 2017 since it may be reduced due to donations being diverted to the campaign in California as described in our Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)—but we expect that HSUS could help fill a gap in HSUS FAP’s budget in this case; 2019 revenue and expenses are based on goals expressed in the Follow-Up Questions for HSUS FAP (2018); all estimates of assets are based on the difference between revenue and expenses added to the previous year’s assets.

“A lot of our goals and long-term plans, particularly in the legislative division, will be determined by whether or not we win Proposition 12 in California later this year. If we do win, we’ll determine the next legislative priorities and continue down the path of criminalizing the cage confinement of farm animals.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

“In the corporate reform division, we want to get all major companies to adopt our broiler chicken policy. […] For those companies who have already adopted the broiler chicken policy, we want to now get more plant-based products on their menus.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

In 2017, this was their largest program by expense, costing $1,580,300. This information can be found in HSUS FAP’s Budget (2017–2018).

HSUS FAP reports having spent $750,000 on welfare campaigns in 2017. This information can be found in HSUS FAP’s Budget (2017–2018).

This range is a subjective confidence interval (SCI). An SCI is a range of values that communicates a subjective estimate of an unknown quantity at a particular confidence level (expressed as a percentage). We generally use 90% SCIs, which we construct such that we believe the unknown quantity is 90% likely to be within the given interval and equally likely to be above or below the given interval.

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for HSUS FAP.

The method we use does calculations using Monte Carlo sampling. This means that results can vary slightly based on the sample drawn. Unless otherwise noted, we have run the calculations five times and rounded to the point needed to provide consistent results. We did this by first rounding the 5% and 95% estimates given in Guesstimate to the nearest $10,000 and then taking the most extreme of the five estimates (the highest value for an upper bound and the lowest value for a lower bound) and rounding it outwards to the next $100,000 when the numbers are in the millions and to the next $10,000 when the numbers are in the tens or hundreds of thousands. For instance, if sometimes a value appears as $2.7 million and sometimes it appears as $2.8 million, our review gives it as $2.9 million if it were an upper bound and as $2.6 million if it were a lower bound.

According to HSUS FAP’s Budget (2017–2018), they spent $90,000 on Food Forward Culinary Experiences and $72,000 on Food Forward Events.

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for HSUS FAP.

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for HSUS FAP.

The percentages used in this chart are based on the mean size of each funding gap.

“Our work on ballot measures means that there is really no limit to the amount of funding that we could use. […] With $2 million more, for example, we could do a lot more in our plant-based work. For example, this kind of funding could be used to hire more chefs to work with our food industry partners.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for HSUS FAP.

Note that all estimates factor in associated supporting costs, including administrative and fundraising costs, sometimes referred to as “overhead.” We assume that these costs are evenly allocated across each intervention.

We consider all seven of our evaluation criteria to be indicators of cost effectiveness. If we were able to model charities’ actual cost effectiveness with very high confidence, we would make our recommendations based heavily on our cost-effectiveness estimates (CEEs). The most cost-effective charities are, after all, the ones that allow donors to have the greatest positive impact with their donations. Even given the risks and uncertainties described above, directly estimating cost effectiveness is one of the best ways we know for identifying highly cost-effective programs.

Cost-effectiveness estimates are sometimes useful for comparing different charities or interventions to one another. We develop CEEs using a consistent methodology and consistent data so that our CEEs for similar charities are meaningfully comparable. Though there are many sources of error that might influence our estimates of the effects of a given charity or intervention, most sources of error would likely apply to all models and thus are unlikely to affect comparisons between models.

We find that, in some ways, the quantitative components of our evaluations are easier for our readers to interpret than the qualitative components. Assigning numbers to uncertain values allows us to be clear about the effects we expect an intervention to have, and it allows our readers to identify specific points on which they may disagree. If our evaluations were entirely qualitative in nature, it might be harder for people who disagree with us about the effectiveness of a program to pinpoint the source of their disagreement—since our qualitative statements are more open to interpretation than our quantitative ones.

For more information, see ACE’s page “Our Use of Cost-Effectiveness Estimates.”

HSUS FAP provided a budget projection for 2018. After redistributing non-program related costs proportionately across their programs, we use this as an estimate for 2018 in total. For more information, see HSUS FAP’s Budget (2017–2018), and ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for HSUS FAP.

For more information, see ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for HSUS FAP.

HSUS FAP provided a budget projection 2018. After redistributing non-program related costs proportionately across their programs, we use this as an estimate for 2018 in total. For more information, see HSUS FAP’s Budget (2017–2018), and ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for HSUS FAP.

For more information, see ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for HSUS FAP.

HSUS FAP provided a budget projection 2018. After redistributing non-program related costs proportionately across their programs, use this as an estimate for 2018 in total. For more information, see HSUS FAP’s Budget (2017–2018), and ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for HSUS FAP.

HSUS FAP provided a budget projection 2018. After redistributing non-program related costs proportionately across their programs, use this as an estimate for 2018 in total. For more information, see HSUS FAP’s Budget (2017–2018), and ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for HSUS FAP.

For more information, see our ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for HSUS FAP.

In fact, there are already sources of error and imprecision in our estimates at this point, most notably in uncertainties about how much time HSUS FAP employees spend on each activity we have described and about how administrative and fundraising costs should be assigned to the various areas. However, the amount of error in our following estimates can be expected to be considerably greater.

We use similar assumptions for each of the groups for which we perform such a calculation. Other estimates of the cost-effectiveness of charities may use different assumptions and therefore may not be comparable to ours.

These factors include the number of animals affected by corporate policy changes associated with HSUS FAP, the extent to which HSUS FAP worked with other groups to achieve those victories, the extent to which these policy changes are accelerated as a result, and the proportion of suffering alleviated by those policy changes.

Sometimes our estimated cost-effectiveness ranges include negative numbers. This does not necessarily mean we think those interventions are equally as likely to harm animals as to help them. It might simply mean that we think—often due to uncertainty around a particular factor—that it’s possible that an intervention could have a negative effect, even if we think that’s very unlikely.

These factors include the number of animals affected by corporate policy changes associated with HSUS FAP, the extent to which HSUS FAP worked with other groups to achieve those victories, the extent to which these policy changes are accelerated as a result, and the proportion of suffering alleviated by those policy changes.

Sometimes our estimated cost-effectiveness ranges include negative numbers. This does not necessarily mean we think those interventions are equally as likely to harm animals as to help them. It might simply mean that we think—often due to uncertainty around a particular factor—that it’s possible that an intervention could have a negative effect, even if we think that’s very unlikely.

To equate the proportional welfare improvements created by corporate campaigns to a figure for animals spared, we make the assumption that X% improvement is equal to X% of an animal being spared. E.g. 10 hens experiencing a 10% improvement in welfare is equal to 1 hen experiencing a 100% improvement in welfare.

Guesstimate, the software we use to produce the models, performs calculations using Monte Carlo simulation. Each time the model is opened in Guesstimate, it reruns the calculations. As Monte Carlo simulation relies on a sample of randomized numbers, the results can vary slightly based on the sample drawn. Thus, in order to ensure consistency, we have run the calculations five times and rounded to the point needed to provide consistent results. For instance, if sometimes a value appears as 28 and sometimes it appears as 29, our review gives it as 30.

The ranges from five computations from the Guesstimate model were: -4.3 to 13.5, -4.1 to 13.9, -4.5 to 14.1, -4.6 to 13.6, and -4.7 to 13.1 farmed animals spared per dollar HSUS FAP spent.

Different farmed animals are raised for different lengths of time prior to slaughter, and so only considering the “number of animals spared per dollar” does not always give a complete picture of the total amount of suffering averted. Our unit, “years of farmed animal life spared per dollar,” factors in the average length of life of each species to better quantify the amount of suffering that has been reduced.

Sometimes our estimated cost-effectiveness ranges include negative numbers. This does not necessarily mean we think those interventions are equally as likely to harm animals as to help them. It might simply mean that we think—often due to uncertainty around a particular factor—that it’s possible that an intervention could have a negative effect, even if we think that’s very unlikely.

The ranges from five computations from the Guesstimate model were: -0.4 to 3.8, -0.4 to 3.7, -0.4 to 3.6, -0.4 to 3.7, and -0.4 to 3.6 farmed animals spared per dollar HSUS FAP spent.

For more information, see our ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for HSUS FAP. Our estimates in this model were calculated using preliminary budget numbers provided by HSUS FAP and HSUS FAP’s reported accomplishments.

For more information, see HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview.

For more information, see HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview.

For more information, see HSUS Farm Animal Protection 2017 Overview.

“To give a sense of the size of these companies, we can compare them to other food service companies in the United States. We recently worked with the company Creative Dining, for example, which is in the top 20 largest food service companies, and they have about 100 accounts (i.e. schools, universities, hospitals, and other institutions that they serve). In contrast, Compass Group has about 10,000 accounts.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

“As one example with Aramark, it has an account with Arizona State University (ASU), the largest university in the United States. In just one day, about 80,000 people purchase food on the ASU campus, and they will now be exposed to our new plant-based menu items and their dining staff will have in-depth plant-based culinary training options. Our goals with shifting dining operations to focus on plant-based meals is to make them delicious enough to attract everyday meat eaters and to market them in a way that encourages meat eaters to order them.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

“We ask these institutions to review how much meat they served up until the introduction of our plant-based products, and then ask them to report whether that amount has changed—and if so, by how much.” —Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Josh Balk of HSUS FAP (2018).

For more information, see our Follow-Up Questions for HSUS FAP (2018).

“In 2007, the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) investigated the Hallmark premises and uncovered cruelty to “downer” cows, in violation of sections 597(a) and 599(a) of the California Penal Code […] the Hallmark scandal fueled the Proposition 2 campaign, which mobilized thousands of Californians to register voters and collect signatures for the November 2008 election” —Thapar. (2011). Taking (Live)Stock of Animal Welfare in Agriculture: Comparing Two Ballot Initiatives. N. 22 Hastings Women’s L.J., 317.

For more information on HSUS’ involvement in Proposition 2, see The New York Times’ article “The Barnyard Strategist.”