Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2018 |

| Current Version | 2022 |

Archived Version: November, 2018

What does Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira do?

The Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (SVB) was founded in 2003. They promote plant-based diets by organizing veg fests, promoting Meatless Mondays, administering a Vegan Label, and working with restaurants to increase vegan offerings through their Vegan Option Program. SVB also works with health professionals to spread knowledge of the health benefits of a plant-based diet. They offer a 16-hour course and have begun organizing a plant-based conference for health professionals in 2018.

What are their strengths?

SVB has many reliable revenue streams, which we consider a positive indication of their organizational stability. We think that SVB is willing and able to assess their areas of success and failure, allowing them to become more effective as they evolve their strategic plan. SVB works collaboratively with Humane Society International (HSI) and Mercy For Animals (MFA), and they seem to prioritize reducing duplication of efforts. They have a strong institutional outreach program that has resulted in the removal of animal products from close to 50 million meals per year. Because they base their message not only on animal welfare but also on health and the environment, they are able to work collaboratively with groups outside of the animal welfare movement such as the Brazilian Ministry of Health. They also help to increase the visibility of plant-based foods through their Vegan Label and the Vegfest Brasil.

What are their weaknesses?

Having almost doubled their staff in recent years, SVB is still adjusting to their expansion. It’s our view that they don’t currently have enough formal policies in place to ensure sustainable growth. While we are confident in SVB’s current strategic plan which outlines measurable goals for each of their programs, we are concerned by the fact that they only recently developed a multi-year strategic vision. Finally, though we believe that dietary change advocacy can be an effective tool to help animals, we think that SVB may be overlooking other effective ways to reduce suffering, such as legal advocacy.

Why do we recommend them?

SVB operates in Brazil, a country that we view as a target for pursuing large-scale change for farmed animals. While other organizations are also engaged in promising work in Brazil, SVB has the advantage of being a local group as opposed to a branch of an international organization. We think this factor could give them more credibility and enable them to better influence public opinion through their outreach. Given their focus on effectiveness and their ability to assess areas of success and failure, we think that donors who are interested in bringing about large-scale change for animals in Brazil should consider donating to SVB.

Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira has been a Standout Charity since November 2018.

Table of Contents

- How Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira Performs on our Criteria

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Questions for Further Consideration

- Supplementary Materials

How Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira Performs on our Criteria

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Before investigating the particular implementation of a charity’s programs, we consider their overall approach to animal advocacy in terms of the cause(s) they advance and the types of outcomes they achieve. In particular, we consider whether they’ve chosen to pursue approaches that seem likely to produce significant positive change for animals—both in the near and long term.

Cause Area

SVB focuses primarily on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we believe is a high-impact cause area.

Types of Outcomes Achieved

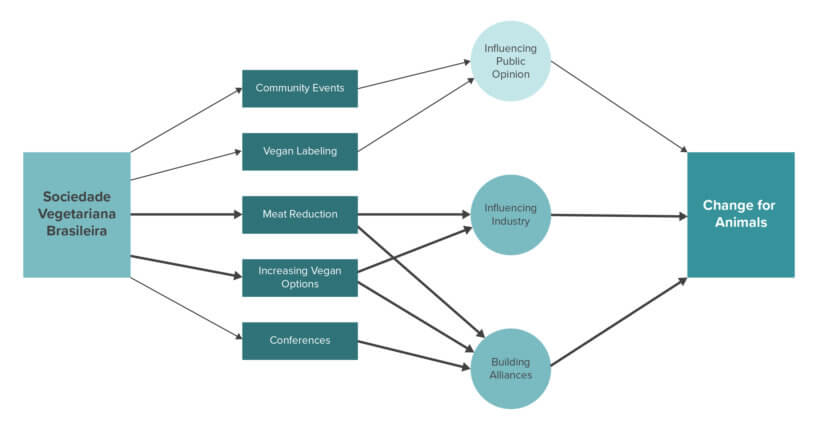

To better understand the potential impact of a charity’s programs, we’ve developed a menu of outcomes that describes five avenues for change: influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

SVB pursues two different avenues for creating change for animals: they work to influence public opinion and build alliances. Pursuing multiple avenues for change allows a charity to better learn about which areas are more effective so that they will be in a better position to allocate more resources where they may be most impactful. However, we don’t think that charities that pursue multiple avenues for change are necessarily more impactful than charities that focus on one.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small and/or uncertain effects.

Influencing Public Opinion

SVB works to influence individuals to adopt more animal-friendly attitudes and behaviors. While it is difficult to measure incremental changes in public opinion—and, consequently, difficult to know when an intervention is more or less successful—we still think it’s important for the animal advocacy movement to target some outreach toward individuals. This is because a shift in public attitudes and consumer preferences could help drive industry changes and lead to greater support for more animal-friendly policies. However, we find that efforts to influence public opinion seem much less neglected than other categories of interventions in the United States.1 While we do not have direct evidence for the situation outside the U.S., we would expect it to be broadly similar to the U.S.

Annually, SVB hosts Vegfest Brasil, Latin America’s largest veg fest. At the 2017 Vegfest Brasil, SVB launched a campaign, Vegetarianism Against Cancer, that provides information and testimonials from doctors about the link between animal product consumption and cancer.2 SVB also has a Vegan Label, which could lower the entry barrier for consumers who are new to veganism by making it easier for them to identify vegan products.3 Due to a lack of evidence, it’s unclear what the actual impact of vegan labeling is on consumer purchases or recidivism. While there isn’t sufficient evidence to be confident of the short-term impact of any of these programs, we’re optimistic that in the long term, they may contribute to more people following plant-based diets.

Building Alliances

SVB’s outreach to key influencers, work with restaurants, and institutional meat reduction campaign provide an avenue for high-impact work, since they involve potentially convincing a small number of powerful people to make decisions that could influence the lives of millions of animals.4 Unless these key influencers are significantly more difficult to reach, this seems more efficient than general individual outreach because a great deal more individuals would need to be reached to create an equivalent amount of change.

SVB has worked to build a high level of participation in the Meatless Monday campaign in Brazil, in which schools and other public institutions served 47 million meatless meals in 2017.5 They also work with restaurants to increase vegan offerings through their Vegan Option Program and have influenced around 400 restaurants to introduce vegan items so far.6 Because these campaigns involve large-scale changes when they are successful, there is potential for significant positive impact.

SVB also works with health professionals to spread knowledge of the health benefits of a plant-based diet through a 16-hour course and, starting 2018, through a plant-based conference for health professionals.7 This year they were also able to work with the Ministry of Health to include positive notes on vegetarian and vegan diets in the Brazilian Dietary Guidelines for Children Under Two.8 While the ultimate impact of this type of work remains to be seen, it is plausible that people may be more receptive to dietary advice from their doctors rather than from activist groups.

Long-Term Impact

Though there is significant uncertainty regarding the impact of interventions in the long term, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.9 The potential number of individuals affected by a charity increases over time due to both human and animal population growth, as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Predictions about the long-term impact of any intervention are always extremely uncertain, because the effects of an intervention vary with context and are interdependent with concurrent interventions—with neither of these interactions being constant over time.10 When estimating the long-term impact of a charity’s actions, we consider the context in which they occur and how they fit into the overall movement. Barring any strong evidence to the contrary, we think the long-term impact of most animal advocacy interventions will be net positive. Still, the comparative effects of one intervention versus another are not well understood.11 Because of the difficulties in forecasting long-term impact, we do not put significant weight on our predictions.

While SVB engages in efforts to impact both individual and institutional change, they are currently directing more resources towards increasing their institutional efforts.12 Their particular institutional approach involves working to replace animal products in the food service industry with vegan products, which we see as having a lower risk of negative outcomes than some other institutional approaches such as cage-free campaigns. In making this shift from individual to institutional outreach, SVB reports that they were motivated partly by having discovered key influencers who were open to their proposals.13 While it’s unclear at any given moment which specific activities will have the greatest long-term impact, being open to shifting resources when opportunities present themselves is likely to contribute to increased impact over the long term.

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

In order to recommend a charity, we need to assess the extent to which they will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. Specifically, we need to consider whether there may be non-monetary “bottlenecks,” or barriers to the charity’s growth. First, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. Next, we evaluate the charity’s room for more funding by considering existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential new programs and areas for growth. It is important to determine whether any barriers limiting progress in these areas are solely monetary, or whether there are other inhibiting factors—such as time or talent shortages. Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for more funding sooner than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we have suggested. Our estimates are intended to indicate the point at which we would want to check in with a charity to ensure that they have used the funds they have received effectively and are still able to absorb additional funding.

Recent Financial History

SVB earns revenue from donations and from several revenue generating programs. In 2017, they took in approximately $260,000; 38% of this came from revenue-generating programs such as events, their Vegan Label, and other product sales.14 Their 2017 expenses were approximately $250,000.

The chart below shows SVB’s recent revenues, assets, and expenditures.15

Planned Future Expenses

SVB plans to build a fundraising department to strengthen their funding situation.16 They would also like to expand their Meatless Monday campaign.17 They recently received a $60,000 grant from the Centre for Effective Altruism’s Animal Welfare Fund to support both of these aims.

Assessing Funding Priority of Future Expenses

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area will likely vary in its potential cost effectiveness. In addition to evaluating a charity’s planned future expenses, we consider the potential impact and relative cost effectiveness of filling different funding gaps. This helps us evaluate whether the marginal cost effectiveness of donating to a charity would differ from the charity’s average cost effectiveness from the past year. We break down the total room for more funding into three priority levels, as follows:

High Priority Funding Gaps

Our highest priority is funding activities or programs that we think are likely to create longer-term impact in a cost-effective way, as well as programs which we have relatively strong reasons to believe will have a highly positive short- or medium-term direct impact in a cost-effective way.18

As described in Criterion 1, SVB has a couple of programs that we consider promising, including their Meatless Monday program and their Vegan Option Program. They reported wanting to expand each of these programs. Of the two, we estimate they have a larger funding gap for their Meatless Monday campaign.19 SVB also reported plans to build a fundraising department,20 which we would consider a high priority since it could contribute to the capacity of their organization. We estimate that SVB has a high priority funding gap of $120,000–$380,000 for 2019.21, 22, 23

Moderate Priority Funding Gaps

It is of moderate priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively moderate marginal cost effectiveness.

SVB has plans to increase staffing and invest more to grow both their Vegan Label program and their events such as Vegfest Brasil.24 We estimate that SVB has a moderate priority funding gap of $90,000–$250,000 for 2019.25

Low Priority Funding Gaps

It is of low priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively lower marginal cost effectiveness, or to replenish cash reserves. Because it is likely that there may be future expenditures we haven’t thought of, we also include in this category an estimate of possible additional expenditures (based on a percentage of the charity’s current yearly budget).

Using a range estimate of 1%–20% of their projected 2018 expenses to account for possible additional expenditures, we estimate that SVB has a low priority funding gap of $0–$70,000 for 2019.26

The chart below shows the distribution of SVB’s gaps in funding among the three priorities:27

SVB has a number of promising programs, and they could likely be more impactful with a significant expansion. In our conversation with their CEO, he said that he thought SVB could effectively use at least an additional $1 million in 2019 to scale up their high-impact programs.28 While we agree that they have high-impact programs that we would like to see expanded, a revenue of $1 million would be almost four times their revenue from last year and we’re skeptical that they could effectively grow that quickly. We estimate that next year they will have a total funding gap of approximately $90,000–$480,00029 and that they could effectively put to use a total revenue of $580,000–$910,000.30

Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

SVB runs several programs; we estimate cost effectiveness separately for a number of these programs, and then combine our estimates to give a composite estimate of SVB’s overall cost effectiveness.31 We generally present our estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. We think that this quantitative perspective is a useful component of our overall evaluation because we find quantitative models of cost effectiveness to be:

- One of the best methods we know for identifying cost-effective interventions32

- Useful for making direct comparisons between different charities or different interventions33

- Useful for providing a foundation for more informative cost-effectiveness models in the future

- Helpful for increasing our transparency34

That said, the estimates of equivalent animals spared per dollar should not be taken as our overall opinion of the charity’s effectiveness. We do not account for some programs that have less quantifiable kinds of impact in this section, leaving them for our qualitative evaluation. For programs that we do include in our quantitative models, our cost-effectiveness estimates are highly uncertain approximations of some of their short-term costs and short- to medium-term benefits. As we have excluded more indirect or long-term impacts, we may underestimate the overall impact. There is a very limited amount of evidence pertaining to the effects of many common animal advocacy interventions, which means that in some cases we have mainly used our judgment to assign quantitative values to parameters.

We are concerned that readers may think we have a higher degree of confidence in this cost-effectiveness estimate than we actually do. To be clear, this is a very tentative cost-effectiveness estimate. It plays only a limited role in our overall evaluation of which charities and interventions are most effective.35

Institutional Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 SVB will spend about 39% of their budget, or $90,000, on a campaign for Meatless Mondays.36 This will result in some institutions adopting new policies, and these policies result in reduced suffering for animals. We estimate that SVB’s institutional outreach will help cause 30–60 million vegan meals to be served in 2018.37

Events

We estimate that in 2018 SVB will spend about 39% of their budget, or $90,000, on running Vegfest Brasil.38

Corporate Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 SVB will spend about 22% of their budget, or $50,000, on corporate outreach.39 This will result in 300 to 550 restaurants implementing vegan options, and 20 to 100 new products carrying the V-Label.

All Activities Combined

To combine these estimates into one overall cost-effectiveness estimate, we translate them into comparable units. This introduces several possible sources of error and imprecision. The resulting estimate should not be taken literally—it is a rough estimate, and not a precise calculation of cost effectiveness.40 However, it still provides some useful information about whether SVB’s efforts are comparable in cost effectiveness to other charities’.41

We consider multiple factors42 to estimate that SVB spares an equivalent of between 25 and 250 animals per dollar spent on institutional outreach.43

We exclude their events and corporate outreach programs from our final cost-effectiveness estimates and don’t attempt to convert them into an equivalent animals spared figure; our estimates for the number of animals this may impact were too speculative to include here.

We weight our estimates by the proportion of funding SVB spends on each activity; overall, we estimate that in the short term—after excluding the effects of some of their programs—SVB spares between 10 and 100 farmed animals per dollar spent.44, 45 This equates to between 4 and 45 years of farmed animal life spared46 per dollar spent.47, 48, 49 Because of extreme uncertainty about even the strongest parts of our calculations, we feel that there is currently limited value in discussing these estimates further. Instead, we give weight to our other criteria.

Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

To evaluate a charity’s track record, we consider how well the charity has executed previous programs. We also consider the extent to which these previous programs caused positive changes for animals. Information about a charity’s track record helps us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments—information that cannot always be incorporated into the criteria above. An organization’s track record can be a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences in other important factors.

Have programs been well executed?

SVB was founded in the early 2000s. One of their major strengths is reportedly the strong positive reputation that they have built up over the last 15 years.50, 51 Among SVB’s programs, their Meatless Monday campaign may be one of their greatest successes. They report that 48 million vegan meals were served in 2017 as a result of their campaigns,52 and that millions of students will be reached by these Meatless Monday programs.53 It is worth noting that HSI also appears to have played a substantial role in these campaigns; SVB focused mostly on São Paulo while HSI was responsible for implementing the program in numerous smaller cities in other regions.54

Another program that SVB executed alongside HSI was their Vegan Option Program. We think that the program was well executed, given that it reportedly resulted in about 400 non-vegan restaurants—particularly fast food chains—offering a vegan option.55 SVB hosts Vegfest Brasil—the largest vegetarian event in Latin America56—as well as film festivals in various Brazilian cities.57 The Vegfest appears to be gaining popularity,58 indicating that it was probably well executed in previous years. In addition, their Vegan Label program covers hundreds of products across roughly 70 companies.59 They report offering regular courses and workshops for medical doctors and other health professionals60 to build alliances with them.61 They’re also successfully working with the Ministry of Health to ensure that plant-based diets are fittingly highlighted in the official Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian population.62

Have programs led to change for animals?

Given Brazil’s relatively large population and high per capita meat consumption, we think SVB’s work has the potential to impact a large number of animals. Their programs seem to have contributed to some positive changes so far. For example, the meat reduction policies that SVB worked with HSI to implement in schools and hospitals reportedly resulted in 47 million meat-containing meals being replaced by meatless meals in 2017.63 This change will reduce the demand for animal products; we estimate that it will spare between 3 and 21 million animals from being used and killed in factory farms.64 However, HSI also deserves credit for the meals that were served as a result of this program outside of São Paulo.65

We hope that SVB’s work to influence restaurants to add vegan options will help to reduce the demand for animal products by improving the available alternatives. It may also improve public knowledge about vegan food. In addition, their work with institutions to certify meat-free products may decrease recidivism by making avoidance of animal products a more convenient choice, potentially causing decreases in animal product consumption.

The impact of some of SVB’s other programs is difficult to measure. For example, the courses and workshops that they offer for medical professionals may have a long-term impact on public perceptions of veganism, but we are uncertain of the number of animals they will actually affect. The Vegfest Brasil is likely to expose people to veganism, which could eventually nudge them towards adopting a vegan lifestyle. While the impact of these programs is difficult to measure, we think that overall, they are potentially valuable and may lead to change for animals in the future.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

A charity that has systems in place for assessing their programs is better equipped to move towards their goals effectively. By conducting self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs, and modify or end those that are less successful. When such systems of improvement work well, many stakeholders benefit: benefactors are inclined to be more trusting and more generous, leadership is able to refine their strategy for achieving their goals, and nonhuman animals benefit more.

To evaluate how well the charity adapts to successes and failures, we consider: (i) how the charity has assessed its past programs and (ii) the extent to which the charity updates their programs in light of those assessments.

Does the charity actively assess areas of success and failure?

We think that SVB has a strong desire and ability to assess their success and failure. They have set SMART66 goals in their strategic plan for 2018–2020. For example, one of their goals is to introduce vegan options in at least four “big players,” defined as restaurant chains with more than 150 locations.67 They have shown that they try to ensure that they have specific metrics for every one of their programs. To illustrate, in the case of Meatless Monday, they measure the number of vegan meals served as a result of their efforts, and in their Vegan Option program, they track their success by looking at the number of restaurants participating—roughly 400 to date, including chains.68 They reported that the largest franchise that has participated in their program so far has over one hundred branches. They have not yet reached out to large chains, defined as owning 1,000 to about 3,000 restaurants in the country, but they reported their plan to do so in the future.69

They also put a strong emphasis on assessing programs that they have found to complement their other programs in important ways. For example, they consider their vegan labeling program to be of particular value since it serves multiple purposes: to raise awareness among consumers and producers, and as a source of income. Their goals for this program are also SMART. For example, they intend to have 2,000 products certified with their vegan label by the end of 2019, up from their current number of 700 certified products. Their current revenue from the vegan label is $11,000 and they are aiming for a revenue of $50,000 by the end of 2019.70 While these goals are highly measurable and time-bound, it is unclear to us how they have arrived at those numbers, and whether these targets are achievable. SVB recently commissioned a 2018 poll done by IBOPE, which reported that 55% of respondents would eat more vegan products if they were labeled as vegan.

Does the charity respond appropriately to areas of success and failure?

SVB has shown that they are thinking critically about the relative impact of their various programs, and that they are refining their strategy in accordance to such critical thinking. For example, after comparing their first decade of activities to that of recent years, they opted to shift from focusing mostly on individual behavior change to also focusing on a more institutional approach.71 This shift was due to SVB’s impression that (i) they have a greater impact with fewer resources through institutional change, (ii) they are more capable of measuring impact of institutional change in the short to medium term, and (iii) they found good opportunities to pursue institutional change (i.e. meeting key influencers who were open to SVB’s proposals).72

SVB’s shift towards institutional outreach has not led them to discontinue their individual outreach programs, such as their events and social media outreach;73 rather, it seems to have led them to reexamine the portion of resources that they allocate to each of their programs. They now work both with public institutions, for example through their Meatless Monday campaigns, and with corporations through their Vegan Option program and the vegan labeling. They have found that this shift in focus, along with the fact that they began choosing their institutional targets more carefully, have enabled them to increase their impact exponentially.74 Relatedly, SVB reported two main reasons for focusing on São Paolo: (1) the political climate, and (2) the population density (São Paulo city and São Paulo state account for 10% and 20% of the country’s population, respectively). In light of these reasons, they have found São Paulo to be a strategic place to work with the hope that it could set the standard for the rest of the country.75

They seem to be aware of their specific strengths and weaknesses in implementing their programs. They claimed that the most important change they have made this year to further their impact has been to grow their staff in numbers. In July 2017, they only had nine paid employees and since then, they have almost doubled that number to 17 paid staff. They also seem appropriately cognizant of the challenges that this new development will bring. They reported that they do not expect the impact of these internal changes to occur immediately since they first need to work on staff development, which they (we believe, reasonably) predict will take some time.76 They also seem to be particularly successful at engaging with other organizations in promising endeavors. Most notably, they have collaborated with the Brazilian chapter of HSI on the Meatless Monday campaign, reportedly coordinating with HSI specifically to ensure that they complement each other’s work. For example, SVB took the lead in negotiations with the São Paulo city and state governments, and HSI worked in cities in surrounding regions. SVB also appears to have close relationships with other like-minded organizations working in Brazil, such as MFA. Specifically, SVB collaborates with MFA on their 21-Day Vegan Challenge, an ongoing campaign that they launched three years ago. To that end, they meet regularly for coordination; MFA is responsible for marketing and for guiding the approximately 50,000 subscriptions, while SVB runs all social media activities.77 We find that SVB’s awareness of the similar work being done by these other organizations allows for more effective collaborations insofar as these collaborations (a) lead to a clear division of tasks, (b) help them to capitalize on each other’s strengths, and (c) help them to avoid unnecessary overlap in their work. It is our hope that SVB will continuously demonstrate their ability and willingness to recognize their organizational strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and opportunities, and then make calculated changes in response.

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

A charity is most likely to be effective if it has a well-developed strategic vision and strong leadership who can implement that vision. Given ACE’s commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we generally look for charities whose direction and strategic vision are aligned with that goal. A well-developed strategic vision must be realistic to manage and execute. It is likely the result of well-run, formal strategic planning; when a charity’s leaders regularly engage in a reflective strategic planning process, revisions and improvements to the charity’s strategic vision are likely to follow.

Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-composed board?

SVB is led primarily by President Ricardo Laurino, CEO Guilherme Carvalho, and Campaigns Manager Mônica Buava. Our sense is that Laurino serves more of a public-facing role while Carvalho and Buava are more involved in SVB’s daily operations. Honorary President Marly Winckler also plays a key leadership role in the organization.78

Both Laurino and Carvalho serve on SVB’s board, along with 17 other entrepreneurs, physicians, professors, and other professionals.79 According to U.S. best practices, boards should consist of at least five individuals who have little overlap with the relevant organization’s staff.80 The evidence for the importance of board diversity is somewhat stronger than the evidence recommending board sizes of five or greater, in large part because there is some literature indicating that team diversity generally improves performance.81 However, to our knowledge, the evidence of the impact of board diversity on organizational performance is less strong than the evidence of the impact of team diversity.82

Given the large size of SVB’s board and the diverse occupational backgrounds of its members, we feel that the board is likely to represent a diverse array of viewpoints. It does not especially concern us, then, that it includes two members of SVB’s leadership team.

Does the charity have a well-developed strategic vision?

Does the charity regularly engage in a strategic planning process?

SVB has developed a strategic plan for 2018–2020. The plan was developed by Laurino, Carvalho, Winckler, Buava, and the organization’s other department heads. A draft of the strategic plan was submitted to the board for feedback and approval, and then it was finalized.83

Does the charity have a realistic strategic vision that emphasizes effectively reducing suffering?

SVB is a vegetarian society. They are focused on promoting plant-based diets, not explicitly on reducing suffering, though those two goals may often overlap. We believe that promoting plant-based diets does reduce suffering to the extent that it causes a reduction in the number of animals being raised for food.

SVB has identified three “pillars” on which they base their work: animals, the environment, and health. They are considering adding food justice as a fourth pillar.84 They believe that framing their work as supporting multiple cause areas allows them to work more effectively with different groups. For instance, their focus on health has led them to collaborate with Brazil’s Ministry of Health,85 which they likely wouldn’t have had an opportunity to do if they presented themselves strictly as an animal charity.

Does the charity’s strategy support the growth of the animal advocacy movement as a whole?

In our view, SVB fills an important niche in the animal advocacy movement simply in virtue of where they operate. Brazil has a relatively large population and high per capita meat availability, making it a target for pursuing large-scale change. Moreover, the Brazilian animal advocacy movement is still relatively young. We think that animal advocacy in Brazil—especially farmed animal advocacy—has the potential to be highly impactful.

Within Brazil, SVB collaborates with many other organizations. For instance, they collaborate with Forum Animal and work to ensure that the two groups’ work does not overlap. SVB directs all advocacy opportunities that aren’t related to farmed animals to Forum Animal.86 SVB also has a collaborative relationship with HSI and MFA.87

SVB sees their work as complementary to the work of other organizations operating in Brazil. Whereas Forum Animal, HSI, MFA, and Animal Equality all work on welfare reforms, SVB works only on promoting plant-based diets. In their view, working on welfare reforms “would not be strategic,” since so many other groups are already working in that area.88 We believe that the animal advocacy movement in the U.S. has shown that it can be useful to have many different organizations working on welfare reforms, particularly if they are using different tactics. However, we think it’s possible that by focusing on the environment, health, and social justice in addition to animal welfare, SVB might be able to reach a wider base of supporters in Brazil.89

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Effective charities are generally well-managed on an operational level; they should have healthy cultures and sustainable structures. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about their human resources policies and their perceptions of staff morale. We also speak confidentially with non-leadership staff or volunteers at each charity to solicit their perspectives on the charity’s management and culture.90 Finally, we send each charity a culture survey and request that they distribute it among their team on our behalf.91, 92

Does the charity have a healthy culture?

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly towards all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. One important part of acting responsibly towards stakeholders is protecting employees from instances of harassment and discrimination in the workplace. Charities that have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, since varied points of view improve a charity’s ability to respond to new situations.93 A healthy charity is transparent with donors, staff, and the general public and acts with integrity; in other words, their professed values align with their actions.

Does the charity communicate transparently and act with integrity?

Respondents to our staff survey generally indicated that they feel SVB is transparent with donors about what their donations are being used for. We have no reason to doubt the transparency of integrity of SVB, though we note that we are less familiar with SVB than we are with many of the other organizations that we evaluate. This is both because (i) this is our first review of SVB, and (ii) SVB operates in Brazil, where we have fewer contacts than in some other countries.

SVB’s internal communication appears to be open and transparent. They recently instituted weekly staff meetings via Skype to keep staff up to date on one another’s activities.94 SVB’s leadership seems readily available to answer questions and receive feedback from staff—a point that was emphasized by Carvalho in our conversation with him and confirmed by staff responses to our survey.95

Does the charity provide staff and volunteers with sufficient benefits and opportunities for development?

SVB does not offer benefits or formal staff development opportunities. Several staff mentioned to us that they knew they could earn a higher salary and more benefits elsewhere, but they were happy to be working for a cause they care about. Though no formal development opportunities are available, staff report that other staff members and leadership are generally available to offer advice and support when needed.

Carvalho reports that SVB offers some staff training at their annual meetings, but that not all staff are able to attend because of the expense.96 He recognizes the need for SVB to further develop their training policies, especially as their organization grows.97 We feel that it’s also important for SVB to cover the costs of all trainings so that everyone on their staff can attend.

Does the charity have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion?

SVB does not have a formal statement in support of diversity and inclusion, nor do they have policies in place to promote those values within their organization.98 Some respondents to our survey reported that SVB could take more steps to be inclusive of marginalized groups; for example, several suggested that SVB should make an effort to invite speakers to its events that are more diverse and representative of SVB’s own staff.

Carvalho tells us that SVB does not “discriminate based on religion, race, or sexual orientation.” and that while many animal charities lack diversity, SVB is happy that their team is “at least somewhat diverse at time.”99 We believe that SVB could benefit from providing staff trainings on diversity and inclusion.

Does the charity work to protect employees from harassment and discrimination in the workplace?

We are not aware of any instances of harassment or discrimination at SVB. However, we recognize that there are numerous reasons why we might not be privy to such information if it does exist, and are therefore cautious not to take this lack of information as evidence that SVB is free of any issues with harassment or discrimination.

SVB does not provide staff trainings on harassment and discrimination, and we are not aware of any formal policies that they have to protect their employees from these issues. According to Carvalho, they “have discussed the issue and […] would like to put mechanisms in place in the near future. For the time being, [they] are learning how to run what has quickly evolved from a small grassroots group into a medium-sized organization.” SVB may want to consider simply implementing a policy that has already been developed by another group; for instance, Tofurky has developed quite a comprehensive policythat other animal charities are already beginning to adopt.

Importantly, while some staff recognized a need for more trainings on harassment, they generally reported feeling comfortable approaching SVB’s leadership with any problems related to harassment or discrimination.

Does the charity have a sustainable structure?

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in which current leadership might move on to other projects. The charity should seem unlikely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, they should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

Does the charity receive support from multiple and varied funding sources?

SVB earns revenue from donations, as well as from several revenue generating programs. In 2017, they took in approximately $260,000; 30% came from revenue-generating events, 7% came from their Vegan Label and other product sales, and 38% came from membership fees and other donations—the rest came from other miscellaneous sources.100 It is our understanding that they have several significant sources of funding, which is a positive indication of their organizational stability.

Does the charity seem likely to survive potential changes in leadership?

SVB was founded in 2003 and has successfully undergone one change in leadership when President Ricardo Laurino took over for Honorary President Marly Winckler. SVB has recently expanded its team quite substantially, and our impression is that there are enough capable managers on the team to oversee other transitions, if necessary.

Questions for Further Consideration

No matter how thoroughly we research a charity, there will always be open questions about some aspects of the charity’s strategy or programming. We’ve asked charities some of those questions, and we present their answers below, without commentary.

Some would argue that the development of new cultured and plant-based food technology will be the key turning point for ending animal farming, and that a shift in public attitudes will naturally follow. What role does SVB play in facilitating the development and acceptance of these new technologies?

SVB’s Response:

“There are two programs through which SVB plays a role in facilitating and strengthening the adoption of plant-based alternatives to meat, dairy and eggs: Selo Vegano (our vegan label program), which supports industries to get the products right, while developing and educating the supply chains; and Opção Vegana (the Vegan Option program), which supports restaurants and the food service sector connecting them with the right suppliers for key ingredients (including new plant-based technologies), while helping them communicate their vegan options in the most effective and profitable way possible.”

Why does a significant portion of SVB’s outreach focus on dietary change, e.g., reducing meat consumption, rather than directly shifting public attitudes?

SVB’s Response:

“We care about having a great impact (i.e., significantly influencing the demand of meat/dairy/eggs) a lot more than we care about attitudes. If a person cuts his/her animal consumption in 50% for health reasons, we’re happy because the impact is there. If a company directs more investments to vegan products for profit reasons, we’re also happy because the impact is there. This impact is, of course, very much about animals, but it is also benefiting the environment and people’s health—and we make sure this does not go unnoticed either.”

SVB focuses on the promotion of veg diets over other ways to help farmed animals, like humane reforms. Do you worry that this means you’re missing out on high-impact campaigns and the ability to build useful connections with food companies?

SVB’s Response:

“We respect and admire the work other organizations do with companies regarding welfare reforms such as cage-free policies, but we do not worry at all about missing out anything and we have no intentions of working with that kind of approach. We are great at what we do, and that is one thing: promoting vegetarianism and reduction of meat, eggs, and dairy. We are confident that there is lots of room to grow on this approach, and being “specialized” in it helps us do our work better, have a clearer ask to institutions and to supporters, use non-animal approaches (such as health and environment) to broaden our reach and impact, and so on and so forth. This allows us to carry out high-impact campaigns, and—through programs such as MLM, Vegan Option and Vegan Label—we have been building meaningful and fruitful connections with strategic food companies.”

;Total Revenue;Assets;Total Expenses 2017;$282,000;$32,452;$249,548 2018 (estimated);$380,000;$188,979;$223,473 2019 (estimated);$520,000;$338,979;$370,000

,Lower estimate,Upper estimate High Priority,120000,260000 Moderate Priority,90000,160000 Low Priority,0,70000

For more information, see our recent research on Allocation of Movement Resources.

“We have launched the campaign Vegetarianism Against Cancer in late 2017 (part of the focus in WHO’s report on processed meat), with more than 60 supporting physicians.” —Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018)

According to a 2018 poll commissioned by SVB and done by IBOPE, 55% of Brazilians would eat more vegan products if they were labeled as vegan. For more information, see the IBOPE summary of the study and this video.

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

For more information, see the Folha de S. Paulo article “No país do churrasco, movimento por um dia sem carne é o maior no mundo.”

“We have had roughly 400 restaurants implement vegan options in their menus through our Vegan Option Program (see for example this video of a recent ice-cream 90-store chain that launched a vegan chocolate ice cream with our participation).” —Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018)

“Taking the workshops from 2016, 2017, and 2018 all together, we have managed to train about 800 professionals so far.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“In February 2018, we joined a Health Ministry commission to discuss the new Brazilian Dietary Guidelines for Children Under Two and were able to insert several positive topics on vegetarian & vegan children (Guidelines should be published by the Brazilian Government later this year).” —Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018)

See the 80,000 Hours article “Presenting the Long-Term Value Thesis” for a more detailed discussion of why long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.

“When outcomes of interventions are interdependent, the effectiveness of each is inextricably linked with those of the others. Justifying one as being more effective than another is not quite straightforward—declaring so is often misleading.” —Sethu, H. (2018) How ranking of advocacy strategies can mislead. Humane League Labs.

See our report on leafleting for a more detailed consideration of the potential long-term impact of a particular intervention.

For more information, see Follow-Up Questions for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (2018).

For more information, see Follow-Up Questions for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (2018).

For more information, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018).

The 2017 revenue can be found in Follow-Up Questions for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (2018); the 2017 expenses can be found in Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018); and the 2017 assets were estimated as the difference between revenue and assets for that year. The 2018 revenue estimate is SVB’s fundraising goal as reported in Follow-Up Questions for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (2018). We estimated the 2018 expenses based on their reported expenses for January–October 2018, which they provided in a private communication. We estimated the 2018 assets by adding the 2017 estimate to the difference between the 2018 revenue and expense estimates. The 2019 revenue estimate is based on the fundraising goal they reported in Follow-Up Questions for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (2018); we estimated the 2019 expenses by taking the average ratio of expenses to revenue for 2017 and 2018; and the 2019 assets were estimated as the difference between estimated revenue and estimated expenses, plus the estimated 2018 assets.

“Fundraising is definitely one of our major weaknesses. We have recently been awarded a grant from the Centre for Effective Altruism and want to use these resources to build a fundraising department.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“Implementing the Meatless Monday campaign, for example, requires a lot of training and follow-up discussions with the participating institutions, both of which are costly. […] Meatless Monday is the main program where we could invest funds that exceed our current fundraising goal.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

The Vegan Option program is currently funded by a grant from HSI, and SVB has applied for another larger grant to expand the program. SVB reported that the marginal impact of additional funding would start to decrease shortly. For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

This range is a subjective confidence interval (SCI). An SCI is a range of values that communicates a subjective estimate of an unknown quantity at a particular confidence level (expressed as a percentage). We generally use 90% SCIs, which we construct such that we believe the unknown quantity is 90% likely to be within the given interval and equally likely to be above or below the given interval.

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

The method we use does calculations using Monte Carlo sampling. This means that results can vary slightly based on the sample drawn. Unless otherwise noted, we have run the calculations five times and rounded to the point needed to provide consistent results. We did this by first rounding the 5% and 95% estimates given in Guesstimate to the nearest $10,000 and then taking the most extreme of the five estimates (the highest value for an upper bound and the lowest value for a lower bound) and rounding it outwards to the next $100,000 when the numbers are in the millions and to the next $10,000 when the numbers are in the tens or hundreds of thousands. For instance, if sometimes a value appears as $2.7 million and sometimes it appears as $2.8 million, our review gives it as $2.9 million if it were an upper bound and as $2.6 million if it were a lower bound.

For more information, see SVB’s Strategic Plan (2018–2020).

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

The percentages used in this chart are based on the mean size of each funding gap.

“We are prepared to effectively use at least $1 million of funding in 2019, increasing our high-impact programs. However, we have not really considered what to do with larger amounts of money.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

Note that all estimates factor in associated supporting costs, including administrative and fundraising costs, sometimes referred to as “overhead.” We assume that these costs are evenly allocated across each intervention.

We consider all seven of our evaluation criteria to be indicators of cost effectiveness. If we were able to model charities’ actual cost effectiveness with very high confidence, we would make our recommendations based heavily on our CEEs. The most cost-effective charities are, after all, the ones that allow donors to have the greatest positive impact with their donations. Even given the risks and uncertainties described above, directly estimating cost effectiveness is one of the best ways we know for identifying highly cost-effective programs.

Cost-effectiveness estimates are sometimes useful for comparing different charities or interventions to one another. We develop CEEs using a consistent methodology and consistent data so that our CEEs for similar charities are meaningfully comparable. Though there are many sources of error that might influence our estimates of the effects of a given charity or intervention, most sources of error would likely apply to all models and thus are unlikely to affect comparisons between models.

We find that, in some ways, the quantitative components of our evaluations are easier for our readers to interpret than the qualitative components. Assigning numbers to uncertain values allows us to be clear about the effects we expect an intervention to have, and it allows our readers to identify specific points on which they may disagree. If our evaluations were entirely qualitative in nature, it might be harder for people who disagree with us about the effectiveness of a program to pinpoint the source of their disagreement—since our qualitative statements are more open to interpretation than our quantitative ones.

Further information about our use of cost-effectiveness estimates is available here.

SVB provided budget information for January–June 2018. After redistributing non program-related costs proportionately across their programs, we multiplied the budget by two to get an estimate for 2018 in total. For more information, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018) and ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

For more information, see ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

SVB provided budget information for January–June 2018. After redistributing non program-related costs proportionately across their programs, we multiplied the budget by two to get an estimate for 2018 in total. For more information, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018) and ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

SVB provided budget information for January–October 2018. From this information, we estimated their spending on each program. For more information, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018) and ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

In fact, there are already sources of error and imprecision in our estimates at this point. Most notably, we are uncertain about how much time SVB employees spend on each activity we have described, and about how administrative and fundraising costs should be assigned to the various areas. However, the amount of error in our following estimates can be expected to be considerably greater.

We use similar assumptions for each of the groups for which we perform such a calculation. Other estimates of the cost effectiveness of charities may use different assumptions and therefore may not be comparable to ours.

These factors include the number of animals affected by corporate policy changes associated with SVB, the extent to which SVB worked with other groups to achieve those victories, the extent to which these policy changes are accelerated as a result, and the proportion of suffering alleviated by those policy changes.

Sometimes our estimated cost-effectiveness ranges include negative numbers. This does not necessarily mean we think those interventions are equally as likely to harm animals as to help them. It might simply mean that we think—often due to uncertainty around a particular factor—that it’s possible that an intervention could have a negative effect, even if we think that’s very unlikely.

Guesstimate, the software we use to produce the models, performs calculations using Monte Carlo simulation. Each time the model is opened in Guesstimate, it reruns the calculations. As Monte Carlo simulation relies on a sample of randomized numbers, the results can vary slightly based on the sample drawn. Thus, in order to ensure consistency, we have run the calculations five times and rounded to the point needed to provide consistent results. For instance, if a value sometimes appears as 28 and sometimes appears as 29, our review gives it as 30.

The ranges from five computations from the Guesstimate model were: 11 to 95, 11 to 92, 12 to 91, 11 to 86, and 11 to 90 farmed animals spared per dollar SVB spent.

Different farmed animals are raised for different lengths of time prior to slaughter, and so only considering the “number of animals spared per dollar” does not always give a complete picture of the total amount of suffering averted. Our unit, “years of farmed animal life spared per dollar,” factors in the average length of life of each species to better quantify the amount of suffering that has been reduced.

Sometimes our estimated cost-effectiveness ranges include negative numbers. This does not necessarily mean we think those interventions are equally as likely to harm animals as to help them. It might simply mean that we think—often due to uncertainty around a particular factor—that it’s possible that an intervention could have a negative effect, even if we think that’s very unlikely.

The ranges from five computations from the Guesstimate model were: 5 to 39, 5 to 41, 4 to 40, 5 to 40, and 5 to 38 farmed animals spared per dollar SVB spent.

For more information, see ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira. Our estimates in this model were calculated using preliminary budget numbers provided in Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018).

“One of our major strengths is the strong reputation we have built up in the 15 years since our foundation. The Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira is considered a reliable partner within the animal and environmental movements. […] Additionally, we are well respected in the political, corporate, and healthcare spheres.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

For an example of SVB’s positive reputation, see the Folha de S. Paulo article “No país do churrasco, movimento por um dia sem carne é o maior no mundo.”

“In 2017, 48 million vegan meals were served as a result of the program. This is mostly due to policies implemented by the governments of São Paulo city and São Paulo state, principally in schools. We also had the support of celebrities like Xuxa which helped the program gain popularity.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

For more information, see ACE’s Brazil roundtable post.

“We took the lead in negotiations with the São Paulo city and state governments, and HSI worked in cities outside of the São Paulo city and state region” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

For more information, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018).

For more information, see ACE’s Brazil roundtable post.

“First of all, this year’s VegFest will be at least three times bigger than last year’s, in part because this year it will take place in São Paulo.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“We launched the program five years ago, and it’s experienced a lot of growth recently—there are now over 700 products from more than 70 brands that are currently using SVB’s vegan label.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

For more information, see ACE’s Brazil roundtable post.

For more information, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018).

For more information, see ACE’s Brazil roundtable post.

For more information, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018).

For more information, see ACE’s 2018 CEE Model for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira.

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

When considering how well charities assess success and failure, one useful consideration is whether their goals are SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. Specific, well-defined goals help guide an organization’s actions, and can help them determine which areas or programs have succeeded and failed. Setting a measurable target allows organizations to determine the extent to which they’ve met their goals. It is also important that goals be plausibly achievable; goals that are predictably over or undershot tell an organization little about how well their programs have done. Goals should be relevant to the organization’s longer-term mission, both to guide their actions and to help them evaluate success. Finally, including time limits is especially important, as it keeps a charity accountable for their expectations of success.

Two additional examples of fairly SMART goals that relate to their Vegan Option program include their plans to have 1,500 restaurants implement vegan options on their menus by 2020, and their goal to hire one more full-time employee for the Vegan Option program by early 2019. For more information, see SVB’s Strategic Plan (2018-2020).

For more information, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

“Over the years, we have been shifting the focus of our work from individual outreach towards a more institutional approach. While we have a very strong presence on social media and a great engagement by followers, we focus most of our efforts on institutional outreach.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“We have strong communication work—which somewhat generates an approach of individual behavioral change—but we have been developing our institutional change approaches more quickly. This has been motivated by a perception that (A) we may get greater impact with fewer resources, (B) we are more capable of measuring impact in the short to medium term, and (C) we found good opportunities (key decision makers or decision influencers that were open to our proposals).” —Follow-Up Questions for Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

“We focused on São Paulo for two main reasons: the political climate and the population density. São Paulo city and state account for 10% and 20% of the country’s population respectively. This, and the political climate, make São Paulo a very strategic place to work in and to set the standard for the rest of the country.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018).

For a full list of SVB employees, see their website’s team page (last checked in October, 2018).

For a full list of Board Members, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018).

See these three standards for nonprofits in the U.S. suggesting between five and seven Board Members as a minimum.

There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that teams composed of individuals with different roles, tasks, or occupations are likely to be more successful than those which are more homogeneous. Increased diversity by demographic factors—such as race and gender—presents more mixed effects in the literature, but gains through having a diverse team seem to be possible for organizations which view diversity as a resource (using different personal backgrounds and experiences to improve decision making) rather than solely a neutral or justice-oriented practice. See our related blog post for more information.

Board demographic diversity in for-profit organizations has been found to be positively correlated with better financial performance. Nonprofit board diversity (in terms of occupation and age) has been found to be positively associated with better fundraising and social performance, better internal and external governance practices, as well as with the use of inclusive governance practices that allow the board to incorporate community perspectives into their strategic decision making. Still, to our knowledge, the evidence of the impact of board diversity on organizational performance is less strong than the evidence of the impact of team diversity.

“The key people involved in developing the plan are: our President; the CEO (myself); the campaign manager; our President of honor (who was President of SVB for 15 years until 2015); and the heads of our scientific, environment, health, and nutrition departments. The strategic plan is then submitted to the advisory board, which includes people from over 30 local volunteer groups from all over Brazil. After the board gives its input, the plan is finalized.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“Currently our three pillars are animals, environment, and health, but we are thinking about adding social justice as a fourth pillar, focusing on things like the fair distribution of food.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“Furthermore, we are currently participating in the elaboration of nutritional guidelines for children under two years of age. The guidelines will be published by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“We have good relationships and collaborate with the main groups in Brazil. Forum Animal is probably the most important local animal protection organization that works on every issue, not just farm animals. They have a program whereby they affiliate with about 100 other groups, of which SVB is one. We redirect all demands that do not relate to farm animals to them. We also make sure that our work does not overlap.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“We also collaborate with the Brazilian chapter of the Humane Society International on the Meatless Monday campaign—we coordinate a lot in order to make sure that we complement each other’s work. […] The division of tasks between HSI and SVB is clear and we can avoid unnecessary overlaps. Our relationship with Mercy For Animals in Brazil is also very close. Specifically, we collaborate with them on our 21-Day Vegan Challenge, an ongoing campaign that was launched three years ago. To that end, we meet regularly for coordination. Mercy For Animals is responsible for marketing and for getting subscriptions, which now amount to roughly 50,000. Meanwhile, SVB runs all social media activities.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“Mercy For Animals, Forum Animal, HSI, and Animal Equality engage in welfare reforms, which SVB is not engaged in at all. Their work as animal organizations is thus complementary to ours as a vegetarian society. For the same reason, it would not be strategic for us to work on welfare improvements ourselves.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“Unlike the animal-focussed groups, we use a variety of different approaches which make it possible for us to work in different environments. The Ministry of Health, for example, would not be interested in interacting with animal charities. Currently our three pillars are animals, environment, and health, but we are thinking about adding social justice as a fourth pillar, focusing on things like the fair distribution of food.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

We speak with two non-leadership staff or volunteers at each charity, except when doing so would not allow us to preserve the anonymity of our contacts (i.e., when charities have fewer than four staff members). Our selections of contacts are random in all dimensions except the following: we aim to select staff members or volunteers who have been with the organization for at least one year (when possible), and we aim to speak with at least one woman and/or person of color from each organization (when possible). To protect our contacts’ confidentiality, what we learn in these conversations is paraphrased in the review, and references to these conversations are identified only as “Private Communication with an Employee of SVB, [Year].” For more information, see our blog post discussing this change, which we implemented in 2017.

We recognize some limitations of our culture survey. First, because participation was not mandatory, the results could be skewed by selection bias. Second, because respondents knew that their answers could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer, they may have felt an incentive to emphasize their employers’ strengths and minimize their weaknesses.

There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that teams composed of individuals with different roles, tasks, or occupations are likely to be more successful than those which are more homogeneous. Increased diversity by demographic factors—such as race and gender—presents more mixed effects in the literature, but gains through having a diverse team seem to be possible for organizations which view diversity as a resource (using different personal backgrounds and experiences to improve decision making) rather than solely a neutral or justice-oriented practice. See our related blog post for more information.

“We also have a short one-hour staff meeting every Friday morning via Skype. We started this three months ago because we decided it would be beneficial to meet more than once a year at our annual meeting. This meeting allows us to bring everyone on the team up-to-date on current projects and objectives.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“[We] have a very healthy and open environment. In addition to being in close contact with the department heads and all staff members, we make sure that everyone has access to me, the President, and the campaign manager. Everyone is free to contact us at any time if they have concerns or complaints. For example, we regularly get feedback from employees about their managers which we address directly with the people involved.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“We train staff accordingly during our annual meetings. These meetings are quite expensive for us because of travel and accommodation costs for each participant. In fact, a few people were not able to attend this year because of the expenses.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“In general, we have been thinking about how to improve staff development for a while now—but just like the rest of HR management, we have a long way to go before there is a well-established process in place.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“At this point in time, we don’t have a formal process in place to encourage diversity in our recruitment and hiring process.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

“Some of our staff members belong to minorities, but not as a result of any specific diversity process. We do not discriminate based on religion, race, or sexual orientation, and we are happy that our team is somewhat diverse at this time.” —Conversation with Guilherme Carvalho of SVB (2018)

For more information, see Sociedade Vegetariana Brasileira’s Accomplishments and Budget (2017–2018).