The Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP)

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2017 |

| Current Version | December, 2019 |

Archived Version: November, 2017

What does The Nonhuman Rights Project do?

The Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) is working to achieve legal personhood and rights for some nonhuman animals. To this end, they are initially litigating—or planning to litigate—on behalf of great apes, elephants, and some marine mammals such as dolphins. Currently, the NhRP is only working on behalf of individual animals who belong to a species for whom there is ample, robust scientific evidence of self-awareness and autonomy. The NhRP views these qualities as sufficient, but not necessary, for recognition of common law personhood and fundamental rights. In addition, the NhRP is developing legal causes of action—manumission, for example—intended to achieve personhood and rights for nonhuman animals regardless of their autonomy.1

In 2017, the NhRP began preparing to pursue legislative work in addition to litigation, though their overarching goal remains the same.

What are their strengths?

Attempting to secure legal personhood and rights for nonhuman animals could be the most promising avenue for improving the lives of animals in our society. As far as we know, the NhRP is the only organization directly pursuing litigation and legislation towards this end, and they seem well prepared to make progress. They have spent substantial effort learning from previous social movements, such as the anti-slavery and LGBTQ+ movements. Additionally, the NhRP’s cases have captured public attention and were even the subject of a 2016 documentary.

What are their weaknesses?

Currently, the NhRP is only working on behalf of individual animals who belong to a species for which there is ample, robust scientific evidence of self-awareness and autonomy. The NhRP believes it will be easiest to achieve legal rights for demonstrably autonomous nonhuman animals, and that doing so is a necessary predicate for achieving legal rights for broader populations of animals.2 Although achieving legal personhood for a small number of animals would be a major achievement in itself, achieving legal personhood for a broader population of animals, such as those used in animal agriculture, would be much more impactful. We are highly uncertain of the extent to which achieving legal personhood for certain great apes, elephants, and/or some marine mammals might increase the chances of achieving legal personhood for broader populations of nonhuman animals.

Why didn’t The Nonhuman Rights Project receive our top recommendation?

We’re excited about the possibility of legal personhood and rights for animals, though we have substantial uncertainty as to whether the NhRP’s work will bring about this end for relatively large numbers of animals. We are also skeptical about ACE’s ability to improve the rate of progress toward such a long-term goal with our recommendation. We think that the best way to increase the likelihood of legal personhood and rights might not be to directly support legal work, but to support social change on behalf of animals that makes people more likely to support legal change.

The Nonhuman Rights Project has been one of our Standout Charities since December 2015.

Table of Contents

- How The Nonhuman Rights Project Performs on our Criteria

- Criterion 1: The charity has room for more funding and concrete plans for growth.

- Criterion 2: The charity engages in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful.

- Criterion 3: The charity operates cost-effectively, according to our best estimates.

- Criterion 4: The charity possesses a strong track record of success.

- Criterion 5: The charity identifies areas of success and failure and responds appropriately.

- Criterion 6: The charity has strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision.

- Criterion 7: The charity has a healthy culture and a sustainable structure.

- Questions for Further Consideration

- Supplementary Materials

How The Nonhuman Rights Project Performs on our Criteria

Criterion 1: The charity has room for more funding and concrete plans for growth.

Before we can recommend a charity, we need to assess the extent to which they will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. Firstly, we look at existing programs that have a need for additional funding in order to fulfill their existing purpose; secondly, we look at potential areas for growth and expansion. It is important to determine whether the barriers limiting progress in these areas are solely monetary, or whether there are other factors such as time or talent shortages. Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, this estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a group could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we have suggested. Our estimates are indicators of the point at which we would want to check in with a group to ensure that they have used the funds they’ve received and are still able to absorb additional funding.

Recent Financial History

When we last reviewed NhRP in 2015, we estimated that they could use around $140,000 in additional funding—depending on the success of their own fundraising—in order to hire up to four new lawyers.1 They have roughly doubled in size since then, making three new hires in the last year2 and increasing their budget to an estimated $890,000 for 2017.3 They did not set a specific fundraising target last year, only a goal of expanding by up to $100,000, which they achieved.4

Planned Future Expenses

In their litigation work, the NhRP currently has two cases involving 3 clients (all chimpanzees) and they are involved in a battle to grant legal rights to these chimpanzees. They have plans to increase the scope of their work, firstly by setting up in states other than New York,5 and secondly by representing other species—for example elephants.6 In order to achieve this they hope to hire one more attorney7—however, we believe that with sufficient funding they could take on an additional two to four attorneys over the next year.

In the last year, the NhRP has branched out from their legal work, and has begun the process of developing the infrastructure for grassroots campaigning—which they hope will complement their legal efforts.8 In the near future they are also planning to start an education program, with the intention of providing advocates and organizations with a better understanding of animal rights.9 To this end, they plan to hire an education Director to head up the program.10

Fundraising has never been a priority concern for the NhRP. As a smaller organization, they reportedly did not have difficulty raising funds.11 However, due to their recent expansion, they have hired a development Director who will establish more structured fundraising goals, allowing them to ensure their progress will be maintained.12

Conclusion

The NhRP thinks that they could roughly double their budget to $1.5 million while still using funds effectively.13 Based on their potential for hiring new staff, and their development of new areas in addition to their legal work, we estimate that they could use $300,000–$700,000 in additional funding over the next year.14, 15, 16 We think it’s likely that no more than half of this additional funding will be attained through their increased fundraising activities.

Criterion 2: The charity engages in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful.

Before investigating the way a charity’s programs are implemented or the outcomes they’ve achieved, we consider the charity’s overall approach to animal advocacy. We expect effective charities to pursue approaches that seem likely to produce significant positive change for animals, though we note that there is significant uncertainty regarding the long-term effects of many interventions.

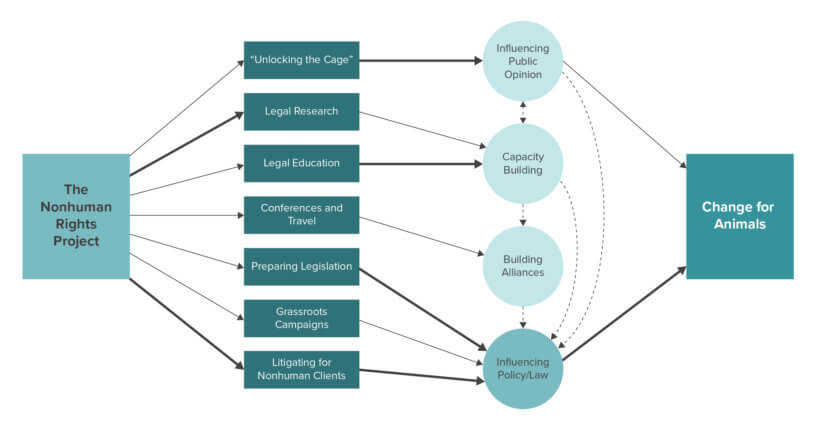

The NhRP focuses on encoding animal rights into law, which we believe is a neglected and potentially high-impact cause area.17 In addition to working to influence policy and law, the NhRP pursues several other avenues for creating change for animals: they work to influence public opinion, build the capacity of the movement, and build alliances. Pursuing more than one avenue for change seems to be a good idea because if one proves to be ineffective, the NhRP still might be impactful. However, we don’t think that charities that pursue multiple avenues for change are necessarily more impactful than charities that focus on one.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not necessarily complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

Influencing Public Opinion

The NhRP works to gain public support for animal rights. We think that the impact of such work may be relatively limited compared to the impact of efforts to influence industry or law. However, we still think it’s important for the animal movement to target some outreach toward individuals, as a shift in public attitudes might be a necessary precursor to achieving more institutional change.

The NhRP was the subject of Pennebaker Hegedus Films and HBO’s 2016 documentary Unlocking the Cage. Since its release, the NhRP has worked with animal advocates to organize and promote screenings of the film. A survey of current vegetarians, vegans, and meat reducers indicates that books and documentaries are common self-reported catalysts for avoiding animal products, and we think that they could plausibly influence political opinion as well.

Capacity Building

Working to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement can have a far-reaching impact. While capacity-building projects may not always help animals directly, they can help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects.

The NhRP conducts legal research that can build the capacity of the movement by educating the legal community on the NhRP’s arguments. For instance, they wrote four law review articles that were published or accepted for publication in 2016 and 2017.18

The NhRP also works to build the animal law field by educating professionals and students of law. President Steven Wise has taught many legal courses over the years and is slated to teach a course at Stanford Law School in Summer 2017.19 We believe that educating students of law on animal advocacy is a high-impact intervention, since many may become lawyers, judges, or policymakers who may have the power to make a difference for animals.

Building Alliances

The NhRP’s outreach to key influencers provides an avenue for high-impact work, since it can involve convincing a few powerful people to make decisions that influence the lives of millions of animals. This seems more efficient than working to reach many individuals in order to create an equivalent amount of change.

The NhRP networks with key influencers by speaking at high-profile law schools and conferences. They also work with other attorneys to promote legal work for animals internationally. There is little evidence about the impact of these interventions.

Influencing Policy and Law

We think that encoding protections for animals into the law is a key component of creating a society that is just and caring towards animals. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects to be particularly long-lasting.

The NhRP uses a unique legal approach to helping animals. Their rights-based litigation approach seeks to provide long-term, stable protection for nonhuman animals under the law. By establishing animals as legal persons and providing a means for advocates to sue on their behalf, the NhRP seeks to establish legal protection first for some nonhuman animals, and perhaps later for many more. In keeping with this long-term focus, the NhRP’s current projects address only the first steps necessary for providing animals with justice through the legal system. Thus, there is room for considerable uncertainty about the eventual impact of their work.

In addition to their litigation approach, the NhRP is developing a legislative component of their strategy.20 Since achieving legal protections for animals would improve living conditions for animals on all farms covered under that law, we see legal work as a potentially high-impact way to help animals. It’s possible that achieving legal protections for animals might also influence public attitudes, either positively (e.g., by raising awareness of animal welfare) or negatively (e.g., by causing complacency or legitimizing the use of animals).

This year the NhRP has invested in developing a grassroots campaigns program to support their future legislative initiatives. Grassroots campaigning has seemed to play an important part in successful animal-friendly legislation in the past, such as with Massachusetts Question 3 in 2016. We think that the NhRP’s work to establish a grassroots coalition is likely to pay off when they begin introducing municipal legislation.

Criterion 3: The charity operates cost-effectively, according to our best estimates.

We think quantitative cost-effectiveness estimates are often useful factors in charity evaluations, but we are concerned that assigning specific figures can be misleading and appear more important in our evaluations than we intended. For the NhRP in particular, we believe that our back-of-the-envelope calculation of their cost-effectiveness is too speculative to feature in our review or include as a significant factor in our evaluation of their effectiveness. For instance, in thinking about their impact we considered the likelihood that legal advocacy leads to the end of animal agriculture; the likelihood that if legal advocacy leads to the end of animal agriculture, the NhRP’s work will be the deciding factor in those events; and the likelihood that the NhRP’s work, while not ending animal agriculture, will combine with other forces to end it one year sooner. Our estimates for all of these factors were very speculative. We considered other unknowns as well, and we omitted many possible scenarios for simplicity.

Additionally, we think the majority of the NhRP’s expected impact is in the medium and long term, and we have not published cost-effectiveness estimates of the medium-term or long-term impacts of any other charities, so we worry that including this cost-effectiveness calculation would be unfair to those other organizations.21 That being said, our lack of a cost-effectiveness estimate doesn’t necessarily indicate that this charity has lower overall cost effectiveness than the charities for which we have completed a cost-effectiveness estimate.

In the future, we hope to have better ways to quantitatively estimate medium-term and long-term impacts, which could lead to publishing a cost-effectiveness estimate for the NhRP. We think cost-effectiveness calculations would still be most useful as one small component in our overall understanding of charity effectiveness.

Criterion 4: The charity possesses a strong track record of success.

Have programs been well executed?

Since late 2013, the NhRP has been litigating cases on behalf of animals; they currently have three active cases involving four clients, all chimpanzees, who have been used in either the entertainment industry or lab research.22 In March 2017 they presented their arguments on behalf of two of their clients to a panel of judges as part of the ongoing legal battle.23 They have also had a few prior opportunities to appear in court on their clients’ behalf, including one instance in 2015 that yielded a decision they felt supported several arguments key to NhRP’s strategy.24 While they have not yet had outright success for any of their clients, we think that the courts’ open reception of what are particularly unusual cases speaks highly of the competence of the NhRP’s legal team.

Another aspect of the NhRP’s operations consists of developing and spreading a legal theory which allows nonhuman animals to be viewed as legal persons. They have been successfully publishing law review articles and other materials on this topic since the 1990s, including four articles in the last two years.25, 26 They have provided a model for this to attorneys in Argentina and Columbia, resulting in the transfer of a chimpanzee from a zoo to a sanctuary, and an ongoing battle for the recognition of the rights of a spectacled bear.27 The success of transferring the chimpanzee in Argentina is probably the strongest evidence we have for the NhRP’s model, and likely means similar successes are replicable in their own cases—although we are unsure of the differences in the court systems of Argentina and the U.S.

In 2016, a documentary was released about the NhRP’s litigation work; since its release, “Unlocking the Cage” has been watched 1 million times through HBO’s platforms and many more times through U.K., French, and German national TV.28 The NhRP has also been helping to organize screenings of the documentary, although this has only resulted in an additional 1,000 views so far.29 This has contributed to the NhRP receiving over 1,000 mentions in media outlets internationally since its release, including major outlets such as The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post.30

Have programs led to change for animals?

Currently, the programs that the NhRP engages in have not led to changes for a significant number of animals, and in the near future we would expect them to lead to changes only for small numbers of animals. Their influence has led to an improvement for the chimpanzee in the Argentinian case, and we think it is likely that further changes will occur for other animals they are representing in their lawsuits.31 Later, we would expect the newly established precedent to have an impact for animals in the same species, or situation, as the animals for whom NhRP has worked directly.

The success of “Unlocking the Cage” may have an impact on the NhRP’s litigation work by increasing public awareness of their cases; however, it is unclear to what extent the film has changed perceptions or acceptance of animal rights in the regions in which the NhRP litigates for animals and whether this would have any impact on the likelihood of those cases being successful.

While the NhRP could ultimately succeed at securing rights for many animals, their track record is limited to their litigation work—which has not yet been impactful for a significant number of individuals. However, we believe that this could be due to the relatively short time they have spent litigating. As such, the expansive and long-term nature of the project indicates potential for future success. As they have only spent a relatively short time litigating, and their project is both long-term and expansive, we do not expect them to have as substantial of a track record as some other organizations or programs.

There may come a point at which the NhRP’s strategy no longer leads to legal progress for animals, while some or all nonhuman animals are still denied legal personhood. For instance, if they are able to establish rights for only the most cognitively complex nonhumans—the chimpanzees, elephant, parrots, and other animals they work with now—they will have significantly less impact than if they can also establish personhood and rights for animals more commonly exploited in our society, such as pigs and chickens.

Our concern that the NhRP’s strategy will lead to change only for a fixed, small proportion of animals used by humans is significant. However, if their strategy is fruitful for all or nearly all animals, their work will be extremely valuable, even if it takes a long time. If substantial other changes are made to animals’ status in society, the legal protections they seek to establish would also help enshrine other changes in the law and ensure their stability.

Another significant concern is that the legal changes pursued by the NhRP may actually not be necessary to produce significant changes in the way animals are treated. It’s possible that social change, as opposed to legal action, could cause the permanent improvements that we, and the NhRP, want to see in how animals are treated. These social changes could then be implemented in law either in the way the NhRP is approaching the problem, or in another way. If this is the case, additional legal work now may not make a significant difference in the ultimate outcome for animals.

Criterion 5: The charity identifies areas of success and failure and responds appropriately.

Since they are working on legal efforts with long-term payoffs, the NhRP cannot easily evaluate their progress in the short term. This is especially the case since they have not been active long enough to observe any significant proximate results, such as rulings in their favor.32 However, they do try to change their efforts to respond to relevant information, both from their own experiences and from other social movements. In addition, they use relevant metrics for particular programs—such as in their individual outreach for fundraising and grassroots campaigning—and they also plan to do this in their upcoming public policy efforts.33, 34 We do not have full information regarding the NhRP’s short-term goals, but they appear to have medium-term targets which are specific, time-bound, and relevant.35

The NhRP sets 1-year and 5-year goals, and they are working on a strategic guiding document that will reflect the current political climate.36 Their goals for legal outcomes appear to have time horizons of multiple years,37 which seems reasonable given the pace of their work so far.38 We hope to see them consider progress on these goals as evidence for their methods’ success and failure in the future. As we have not seen their strategic documents, we are uncertain whether their shorter-term goals are well-designed for self-evaluation—for example, whether they are mission-relevant, describe measurable outcomes, and set specific deadlines.

The NhRP has also demonstrated some willingness to change their approach based on indicators of success and failure, and to seek and respond to relevant evidence. They have told us that they adjust their approach across individual court cases based on which arguments and strategies are successful. In court cases, they are provided with the court’s opinion on which arguments the court had accepted and which they had not, so they can, for example, add to their argumentation to attempt to counter any objections that were raised.39 They have also had difficulty in some cases with the court fully understanding their position, so they have reportedly taken steps to improve their explanations.40

They also try to improve their approach based on other social movements. For example, they have taken lessons from the movement against human slavery, which in many regions successfully raised all humans from the legal status of property to the legal status of persons.41 This has both helped them refine their approach for legal change and suggested to them that legal change is one of the most promising strategies for helping populations who are seen as “things” rather than “persons.”42 For the past few years, they have been in touch with the Freedom to Marry campaign, as they see parallels between NhRP’s work and the movement for same-sex marriage.43

They also decided to start a public policy program focused on animal rights legislation, in part because they have seen animal welfare regulation achieve increased success and social acceptance in recent years.44 Once the program is more developed, they plan to track its success by keeping tabs on the number of bills they have introduced and how far they have reached in the legislative process.45 Our understanding is that they will then publish evaluations of their legislative success on a yearly basis, incorporating assessments of progress as well as data about the number and status of bills.46

Criterion 6: The charity has strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision.

The Nonhuman Rights Project is committed to their work on establishing legal rights for nonhuman animals, a goal which could improve the lives of many animals. However, we are somewhat concerned that their current strategy may turn out to be of limited effectiveness, as it may only succeed for a small number of animals.

While the board is involved in NhRP’s strategic planning,47 we have less of a sense as to whether the organization’s non-leadership staff have a say in this process. We are also concerned that their board is particularly small and insular; we think it is possible that additional members could provide a useful new perspective on the NhRP’s work.

The charity’s mission emphasizes effectively reducing suffering/helping animals.

The NhRP’s mission is “to secure legally recognized fundamental rights for nonhuman animals through litigation, advocacy, and education.”48 This includes the achievement of animal rights worldwide, hence their attempts to collaborate with individuals and organizations outside the U.S.49

We believe that achieving this goal could lead to immense benefits for animals, especially if it is achieved before industrial agriculture is ended by other means. However, the NhRP’s work so far has focused on charismatic, highly intelligent animals (chimpanzees in particular) although they plan to file a lawsuit on behalf of an elephant in the near future.50 As noted in Criterion 4, we are concerned that their methods may not apply to the large number of less well-regarded and less cognitively complex animals harmed by humans—particularly in animal agriculture. While the NhRP’s legal arguments are based on a right to liberty that they believe could be claimed for many animals,51 it seems likely in practice that animals who are easiest for judges, legislators, and citizens to recognize as humanlike will be more likely to be granted rights.

Given their mission and track record, we think it is likely that the Nonhuman Rights Project will remain committed to legal and legislative work that has the potential to effectively help animals. However, we are somewhat concerned that this work’s true impact on animals may be limited to a small number of species, in which case it would likely be ineffective.

The strategy of the charity supports the growth of the animal advocacy movement as a whole.

The NhRP is the only organization we know of working directly for animal personhood in the U.S. They contribute to the animal advocacy movement by working in a neglected area that has the potential for very high impact in the long run. They also help individuals and organizations in the U.S. and many other countries.52 For example, last year they helped organizations in Argentina and Colombia adopt an animal rights litigation model based on habeas corpus requests, which those organizations used to file cases on behalf of a chimpanzee and a spectacled bear respectively. This led to a favorable decision from the Argentinian court, in what the NhRP believes was the first recognition of a nonhuman primate’s legal personhood—as well as a favorable decision from the Colombian court, which was later overturned.53, 54

The board of the charity includes members with diverse occupational backgrounds and experiences.

The NhRP has a three-person board, which includes NhRP’s founder and President Steven Wise, a longtime animal rights lawyer.55 It also includes Wise’s wife Gail Price-Wise, who has a background in diversity training and nonprofit consulting, and the primatologist Jane Goodall.56

According to U.S. best practices, nonprofit boards should be comprised of at least five people who have little overlap with an organization’s staff or other related parties.57 However, there is only weak evidence that following these best practices is correlated with success, and if they are correlated, that may be because more competent organizations are more likely to both follow best practices and to succeed—rather than because following best practices leads to success. Given that the organization’s staff is so small, we believe it is not unreasonable for them to largely take the reins when it comes to setting goals. As a result, the board’s small size alone does not weigh significantly against the NhRP’s effectiveness as an organization.

The evidence for the importance of board diversity is somewhat stronger than the evidence recommending board sizes of five or greater, in large part because there is a significant body of literature indicating that team diversity generally improves performance. However, the evidence we are aware of for the importance of board diversity on organizational performance specifically is less strong.58 Given its size, the NhRP’s board is reasonably occupationally diverse. However, we think the NhRP could benefit from other relevant expert judgment, particularly from those with fewer ties to the organization’s leadership. For example, given their focus on other social movements as a guide to animal rights efforts,59 they might find it helpful to include members or scholars of these movements on their board. As they begin to conduct legal work for non-primates, the NhRP might also find value in the knowledge of biologists with different specialties.

The board of the charity participates regularly in formal strategic planning on behalf of the charity, and involves other stakeholders in that process.

The NhRP conducts strategic planning via regular meetings (once or twice annually) in which the board and the organization’s Directors come together to discuss how their activities relate to the charity’s ultimate goal. At the end of the process, they set short-term goals for a one-year and five-year time horizon.60 They have told us that they require consensus in their decision making, and pride themselves on resolving disagreements through intense and evidence-based debates.61

Criterion 7: The charity has a healthy culture and a sustainable structure.

The NhRP still has a small staff and has only recently added programs outside the courtroom; as such, some aspects of their culture may be changing fairly rapidly.62 One reason the NhRP’s culture may change is that they currently try to make decisions by consensus, but that may become more difficult as they grow larger.63 Another reason is that the NhRP seems well aware of the value a more diverse team would bring to the organization, but still has a mostly white staff.64, 65

The charity receives support from multiple and varied funding sources.

The NhRP is entirely supported by donations.66 The majority of their budget comes from a few donors who have provided the NhRP with significant support over the past several years.67 They recently hired a development Director in order to enable them to expand and pursue legislative initiatives and campaigns.68 They also hope to get more recurring donors, which would likely help increase the stability of their finances.69

The charity provides staff and volunteers with opportunities for training and skill development, helping them grow as advocates.

The NhRP encourages and in some cases requires staff to engage in professional development activities, such as attending conferences and reading books and articles relevant to their work.70 The staff we spoke to confidentially told us that the legal and non-legal teams didn’t interact much and were fairly different from each other, and one way we saw this divide reflected was that the two teams seemed to have different professional development norms.71, 72 The non-legal staff received more direct encouragement to do things they perceived as training or skill development while legal staff believed the organization would support them to do more training if they suggested it, but were not directly encouraged to do so.73

The charity has staff from diverse backgrounds and with diverse personal characteristics (e.g., race, gender, age), and views diversity as a resource that can improve its performance.

The NhRP has a reasonably gender-balanced staff, including among leadership.74 They try to reach out to a variety of communities with their screenings and when recruiting volunteers, in order not to limit their advocacy effort, and they note that they especially need to be prepared to reach a variety of people with their arguments because judges on their cases may come from communities that are typically underrepresented in the animal advocacy movement.75 The staff members we spoke with confidentially noted that the NhRP could improve in terms of the diversity of their staff, but perceived the organization as being open to making changes in order to be more inclusive and as seeing value in hiring people from marginalized communities to help lead more inclusive campaigns.76

The charity works to protect employees from harassment and discrimination.

The NhRP is currently working to draft and implement a policy to prevent harassment and bullying, and to update their anti-discrimination policy.77 We spoke with two non-leadership staff members and performed some due diligence searches, and are not aware of any reports of harassment or discrimination at the NhRP.78

Questions for Further Consideration

Is it possible that, perhaps by acting too soon, the NhRP is actually delaying legal progress for animals?

Some have been critical of the NhRP’s strategy on the grounds that today’s courts are not yet likely to grant legal personhood to nonhuman animals, and unfavorable rulings in cases like Tommy’s and Kiko’s might set a bad precedent. Perhaps it would be better to focus on addressing speciesism now and delay litigation on behalf of animals until it is more likely to succeed.

The NhRP, however, is not concerned that early opinions on the legal personhood of nonhuman animals will negatively influence later opinions. They maintain that, in cases like Tommy’s and Kiko’s, any judge who rules unfavorably must either be acting (i) arbitrarily, irrationally, and/or under the influence of bias, or (ii) incongruously with the values of liberty and equality. As all judges are supposed to be principled, rational, unbiased, and to act in accordance with liberty and equality, the NhRP thinks that unfavorable rulings are likely to be overturned or unrepeated.79

The NhRP points out that, while one court ruled that nonhuman animals cannot be persons because they can’t bear duties and responsibilities, another court has already recognized a problem with that argument in a 2017 case: babies and comatose humans are persons despite their inability to bear duties and responsibilities.80 The 2017 court also ruled unfavorably for Tommy and Kiko on the grounds that membership of the human species is necessary for personhood, but their decision did not appear to be influenced by the previous court’s decision.

If NhRP’s tactics succeed for apes, how likely is it that this success would lead to progress for other animals?

The NhRP argues for the legal personhood of individual nonhuman animals based on their right to liberty. They do not believe that the right to liberty is exclusive to the individuals for whom they litigate; the arguments they’ve developed can be extended to support individuals of other species. The NhRP tells us that they are “frequently consulted not just on the issue of the personhood of nonhuman animals, but on the potential personhood of robots, entities with artificial intelligence, aliens, such species as Neanderthals if they should ever be made to return, and natural objects such as rivers.”

While the NhRP’s work could lead to progress for any species (and perhaps some inorganic entities), some animal advocates still may be concerned that it is not likely to lead to progress for many species of animals. Apes are more similar to humans than other species. They may be seen as more charismatic, and they may be more likely to generate empathy. It’s possible that, even if the NhRP achieves legal personhood for apes, they may never achieve legal personhood for the vast number of animals living on factory farms. Still, we see no reason why the legal personhood of apes would make the legal personhood of farmed animals less likely; it would either have no effect or make it more likely. We believe that, to make progress towards the legal personhood for farmed animals, animal advocates should support efforts to achieve legal personhood for apes in addition to combating the speciesism that makes legal personhood for farmed animals especially unlikely.

Have people’s attitudes or arguments changed over the course of the NhRP’s work? Will it be possible to measure such change in the near future?

The NhRP’s work has gained greater attention in the past few years, particularly as a result of the 2016 documentary Unlocking the Cage. The NhRP tells us that “[t]here has already been steady and measurable substantial progress in the discussion, understanding, and acceptance of the NhRP’s work and arguments outside the courtroom, which is a necessary predicate for being accepted inside the courtroom.”

The NhRP is working with a professor of communications at Fordham University on an investigation of public attitudes towards the legal personhood of nonhuman animals. They plan to use both focus groups and online surveys. Though this investigation alone will not necessarily inform them of the effects of their work, its results could be compared with the results of other studies in order to investigate changes in public opinion over time.

The NhRP also appears to have had an impact in academic law. It has generated discussions in legal journals, academic books, and industry publications.81

To what extent is the NhRP’s approach tractable?

Because we expect the NhRP’s goals to be achievable only in the long term, it’s hard to be certain of their tractability or to assess the NhRP’s progress in the short term. The NhRP, however, does feel they are making progress towards their goals. For instance, in 2015, they successfully used a writ of habeas corpus to require that the holders of two chimps provide legally sufficient ground for holding the chimps captive. Since then, the NhRP tells us that “multiple courts outside the United States (Argentina and the Supreme Court of Colombia) have granted legal personhood to nonhuman animals in habeas corpus cases.” Given that prior to 2015 no court had ever issued a writ of habeas corpus to a nonhuman animal, the NhRP views these cases as indications of their progress.82

“We think they could probably train up to four new attorneys next year. This leads to a need, in the next year, for about $280,000 in additional funding.

The NhRP has also recently hired a fundraiser, so we can expect their own fundraising to increase, filling part of the gap. If half the gap remains, they could use another $140,000 in funding beyond what they raise themselves next year.” —ACE’s 2015 Review of the Nonhuman Rights Project“They added three new positions last year and plan to grow further.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“NhRP did not set a formal fundraising goal last year. Their aim was to grow by several thousand or up to $100,000 and they achieved that.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“By the end of the year, NhRP will have filed another lawsuit on behalf of animals in a state other than New York.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“NhRP will file a lawsuit on behalf of an elephant in the coming months.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“The next priority is to hire another attorney (in order to be able to file more lawsuits at a time).” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“In the past year, NhRP has expanded their mission and they are now also active outside the courtroom. They are building an infrastructure in order to develop a grassroots movement for their rights-based approach which is similar to those of animal protection organizations. NhRP is also preparing their public policy activities and will soon introduce rights-based legislation at both city and state levels. Currently (before they introduce any new initiatives), they are still doing research, thoroughly vetting the issue, drafting legislation carefully, and building a coalition. For much of the past year, they focused on these activities behind the scenes so that when they finally introduce their first piece of legislation, it has a high probability of being passed.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“NhRP also plans to develop an education department. Many animal advocates are not able to give a good explanation of animal rights, so they need training to better understand what [rights] would entail legally. Education will thus be directed at advocates and organizations.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“One of their primary staffing goals is to hire a Director of education.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“Fundraising has never been particularly important for NhRP; they’ve never had difficulties raising the relatively small amount of money needed to run a small organization.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“However, the decision to pursue legislative initiatives and campaigns made it necessary to bring in a development Director and set more formal fundraising goals.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“They estimate that they could almost double their budget to $1.5 million and still use the money effectively, spending it on next year’s campaigns and legislative initiatives.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

This estimation is based on our room for more funding Guesstimate model.

This range is a subjective confidence interval (SCI). An SCI is a range of values that communicates a subjective estimate of an unknown quantity at a particular confidence level (expressed as a percentage). We generally use 90% SCIs, which we construct such that we believe the unknown quantity is 90% likely to be within the given interval and equally likely to be above or below the given interval.

The method we use does calculations using Monte Carlo sampling. This means that results can vary slightly based on the sample drawn. Unless otherwise noted, we have run the calculations five times and rounded to the point needed to provide consistent results. For instance, if sometimes a value appears as 28 and sometimes it appears as 29, our review gives it as 30.

Animal Charity Evaluators is currently working on an intervention report for legal work.

“We had four law review articles, which we write to educate the legal profession and judiciary on the novel legal arguments the NhRP employs in its litigation, published or accepted for publication in 2016 and 2017: 1) a retrospective on the NhRP’s work written by Steven Wise (Syracuse Law Review); 2) an examination of the power of municipalities, through home rule, to enact legislation granting legal rights to nonhuman animals within its municipal borders (Syracuse Law Review); 3) an exploration of the ancient and powerful legal tool of manumission through which a private owner could bestow legal personhood upon his slave (University of Tennessee Law Review), and; 4) an in-depth analysis of the New York State intermediate appellate court’s ruling in People ex rel. Nonhuman Rights Project, Inc. v. Lavery, which for the first time in history made entitlement to legal personhood strictly contingent on the ability of a being to bear social duties and responsibilities (University of Denver Law Review).” —The Nonhuman Rights Project’s Accomplishments (2016–2017)

“Stanford Law School invited Steve to teach a summer course about the NhRP’s work in the summer of 2017.” —The Nonhuman Rights Project’s Accomplishments (2016–2017)

“NhRP is also preparing their public policy activities and will soon introduce rights-based legislation at both city and state levels.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

We have sometimes prepared, but not published, speculative estimates similar to the one that we could have prepared for the NhRP.

They currently represent Tommy, Kiko, and Hercules and Leo.

“Concerning their rights-based litigation, NhRP overcame numerous procedural obstacles to appear before a panel of judges in March 2017 and again present their arguments on behalf of their clients Tommy and Kiko.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

See previous hearing dates on behalf of clients Tommy, Kiko, and Hercules and Leo. Justice Jaffe’s ruling in the Hercules and Leo case is the one the NhRP found to be especially supportive of their arguments.

The NhRP’s media center includes a list of their publications. The earliest is from 1995 and is listed as: Steven M. Wise, “How Nonhuman Animals Became Trapped in a Nonexistent Universe” 1 Animal Law 15 (1995).

“We had four law review articles, which we write to educate the legal profession and judiciary on the novel legal arguments the NhRP employs in its litigation, published or accepted for publication in 2016 and 2017: 1) a retrospective on the NhRP’s work written by Steven Wise (Syracuse Law Review); 2) an examination of the power of municipalities, through home rule, to enact legislation granting legal rights to nonhuman animals within its municipal borders (Syracuse Law Review); 3) an exploration of the ancient and powerful legal tool of manumission through which a private owner could bestow legal personhood upon his slave (University of Tennessee Law Review), and; 4) an in-depth analysis of the New York State intermediate appellate court’s ruling in People ex rel. Nonhuman Rights Project, Inc. v. Lavery, which for the first time in history made entitlement to legal personhood strictly contingent on the ability of a being to bear social duties and responsibilities (University of Denver Law Review).” —The Nonhuman Rights Project’s Accomplishments (2016–2017)

“Provided to attorneys in Argentina and Colombia a model for rights-based litigation on behalf of nonhuman animals via habeas petitions that resulted in 1) the transfer of chimpanzee Cecilia from a zoo to a sanctuary and 2) recognition of the rights of spectacled bear Chucho (the latter decision was overturned on appeal but we are working closely with the attorney who filed the case to help him determine his next steps).” —The Nonhuman Rights Project’s Accomplishments (2016–2017)

“As part of our 2017 Unlocking the Cage campaign, we worked with interested supporters to organize screenings of the film in their respective hometowns, providing both screening licenses free of charge and detailed guidance on event promotion […] The film has been played 1 million times across HBO’s platforms. This does not include the millions more who watched the HBO live broadcasts, BBC, and French/German national TV.” —The Nonhuman Rights Project’s Accomplishments (2016–2017)

“As part of our 2017 Unlocking the Cage campaign, we worked with interested supporters to organize screenings of the film in their respective hometowns, providing both screening licenses free of charge and detailed guidance on event promotion. We have held nine screenings so far, with 21 more in the works. More than 1,000 people have attended a screening of Unlocking the Cage.” —The Nonhuman Rights Project’s Accomplishments (2016–2017)

“In conjunction with both our litigation and the release of the documentary Unlocking the Cage, we secured over 1,000 media hits in major outlets across the U.S. (including NBC News, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, the Associated Press, Law360, Gizmodo, Fox News, Salon, The Baffler, Crux: Taking the Catholic Pulse, Village Voice, and Forbes) and around the world (including the Kremlin Express, Yahoo Japan, Al Hurra in Iraq, Mexico’s Entrelíneas, and India’s Economic Times) the collective potential reach of which, according to our media monitoring service, is approximately 350 million.” —The Nonhuman Rights Project’s Accomplishments (2016–2017)

“Provided to attorneys in Argentina and Colombia a model for rights-based litigation on behalf of nonhuman animals via habeas petitions that resulted in 1) the transfer of chimpanzee Cecilia from a zoo to a sanctuary and 2) recognition of the rights of spectacled bear Chucho (the latter decision was overturned on appeal but we are working closely with the attorney who filed the case to help him determine his next steps).” —The Nonhuman Rights Project’s Accomplishments (2016–2017)

“Measuring success is not straightforward for NhRP, since lawsuits typically take several years to yield any results, and because they have only filed three lawsuits so far.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

Our understanding is that the NhRP began filing lawsuits in 2013, after spending time preparing their legal strategy: “We spent more than 30,000 hours over 17 years (from 1996 to 2013) preparing a complex litigation strategy […] As a result of our tens of thousands of hours of preparation, our litigation is professional and respected[.]” —Statement from Steven Wise of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2015)“NhRP did not set a formal fundraising goal last year. Their aim was to grow by several thousand or up to $100,000 and they achieved that […] [T]he decision to pursue legislative initiatives and campaigns made it necessary to bring in a development Director and set more formal fundraising goals.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“The grassroots campaign has already grown by at least 50% in the last six months and will continue to do so. For the remainder of 2017, NhRP’s public policy department will focus on building a well-trained grassroots “army,” implementing a new advocacy-focused software platform, and developing legislation that will be introduced in 2018.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

When considering how well charities assess success and failure, one useful consideration is whether their goals are SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. Specific, well-defined goals help guide an organization’s actions, and can help them determine which areas or programs have succeeded and failed. Setting a measurable target allows organizations to determine to what extent they’ve met their goals. It is also important that goals be plausibly achievable; goals that are predictably over- or undershot tell an organization little about how well their programs have done. Goals should be relevant to the organization’s longer-term mission, both to guide their actions and to help them evaluate success. Finally, including time limits is especially important, as it keeps a charity accountable to their expectations of success.

“NhRP’s board and Directors meet once or twice per year to discuss their current activities and to talk about how these contribute to the overall aim of achieving as many rights as possible for as many animals as possible. To that end, they set short-term goals for one or five years.

NhRP is working on its own guiding document that is constantly evolving in accordance with the political climate.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)“The timeline in particular seems to get shorter and shorter: just two years ago they would have estimated that it would take another decade and a half before a court recognizes that at least one nonhuman animal has the right to bodily integrity and bodily liberty. At present, however, they are optimistic that this victory can be achieved within the next five years. The goals for the legislation department are similarly short-term: NhRP wants to bring one major city in the United States to pass rights-based legislation for animals within the next two or three years.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

As mentioned in a previous footnote, our understanding is that the NhRP has been filing lawsuits since 2013, so far without a decision in favor of their clients. In our conversation this year, Dominguez also noted that lawsuits often take several years to bear fruit; as a result, we think it is reasonable for them not to set legal victory as a one-year goal. We are uncertain about the plausibility of the specific timelines considered by the NhRP, especially for their new legislative program.

“They try to be as flexible as possible and constantly re-evaluate their arguments and approach in light of how judges react to their arguments. They cast their arguments in terms of values which the judges accept.” —Conversation with Steven Wise and Natalie Prosin of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2015)

“An example of how they learned from experience is the recent Hercules and Leo case. Even though NhRP felt that the arguments from equality and liberty were very simple, the judge did not understand them. So, next time they will reframe the arguments in a more obvious and simple way.” —Conversation with Steven Wise and Natalie Prosin of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2015)

“[O]ur suits are based on a case that was fought in England in 1772, when an American slave, James Somerset, who had been taken to London by his owner, escaped […] [he] was recaptured and was being held in chains on a ship that was about to set sail for the slave markets of Jamaica. With help from a group of abolitionist attorneys, Somerset’s godparents filed a writ of habeas corpus on Somerset’s behalf in order to challenge Somerset’s classification as a legal thing[.] In what became one of the most important trials in Anglo-American history, Lord Mansfield ruled that Somerset was not a piece of property, but instead a legal person, and he set him free.” —Mountain, M. (December 2, 2013). Lawsuit Filed Today on Behalf of Chimpanzee Seeking Legal Personhood. Nonhuman Rights Project.

“Throughout history, there has been a legal wall separating “persons” on the one side, and “things” on the other. Until fairly recently, groups such as nonhuman animals, and such humans as slaves, women, homosexuals, and children have been on the wrong side of the wall: they have been considered to be things rather than persons. Consequently, they have been treated as slaves to the persons on the other side of the wall. Over time, these groups of humans gained the status of persons. The Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) views this as part of a fluid process that will gradually lead to the recognition of the personhood of at least some nonhuman animals. The NhRP is working to gain legal recognition for the personhood of nonhuman animals through litigation.” —Conversation with Steven Wise and Natalie Prosin of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2015)

“During the last couple of years, NhRP has had discussions with (and received guiding documents from) Evan Wolfson of the Freedom to Marry campaign. This has been very helpful, owing to the parallels between achieving rights for nonhuman animals and achieving marriage equality.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

In addition, Dominguez noted in our recent conversation that judges have sometimes met the NhRP’s litigation efforts with the criticism that animal rights should be a legislative issue. While the NhRP thinks judges have the power to establish animal rights, they agree that legislation is a legitimate avenue for their efforts.

“Eventually, they will be able to track how many bills have been introduced and how far they have progressed in the legislative process.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“This data can be obtained annually and compared with the results from the year before. When the first results are in, NhRP will be able to explain to donors what they are doing, how they are doing it, and how they evaluate their work. Currently, NhRP is in the process of building that tracking device.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“NhRP’s board and Directors meet once or twice per year to discuss their current activities and to talk about how these contribute to the overall aim of achieving as many rights as possible for as many animals as possible. To that end, they set short-term goals for one or five years.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“We work to secure legally recognized fundamental rights for nonhuman animals through litigation, advocacy, and education.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“NhRP wants universally recognized animal rights; they do not want to achieve rights for animals in only in one city, state or country. For that reason, they closely cooperate with groups outside the United States. They have […] begun to actively support and work with individuals and organizations in places like India, Israel, South Korea, the E.U., the U.K., and South America.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“In [their] previous review of the organization, ACE wondered whether a litigation approach could be expanded to other species besides chimpanzees. NhRP will file a lawsuit on behalf of an elephant in the coming months.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“The arguments of the NhRP are not geared to any specific species of nonhuman animals. Nor are any species of nonhuman animal excluded.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“They have not only inspired but also begun to actively support and work with individuals and organizations in places like India, Israel, South Korea, the E.U., the U.K., and South America.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“The habeas corpus lawsuit in Argentina that led to the first nonhuman primate being recognized as a person and transferred to a sanctuary was modeled on the NhRP’s litigation.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

The NhRP “[p]rovided to attorneys in Argentina and Colombia a model for rights-based litigation on behalf of nonhuman animals via habeas petitions that resulted in 1) the transfer of chimpanzee Cecilia from a zoo to a sanctuary and 2) recognition of the rights of spectacled bear Chucho (the latter decision was overturned on appeal but we are working closely with the attorney who filed the case to help him determine his next steps).” —The Nonhuman Rights Project’s Accomplishments (2016–2017)

“The three-member board of the Nonhuman Rights Project includes Wise, his wife, Gail Price-Wise, and renowned primatologist Jane Goodall.” —Gavin, R. (2014). “No personhood for Tommy: Appellate court says chimp not entitled to a human’s legal rights.” Times Union.

Price-Wise and Goodall are listed as Board Members on NhRP’s “Our Team” webpage, which links to these pages summarizing their backgrounds.

See these three standards for nonprofits in the U.S. suggesting between five and seven Board Members as a minimum.

We’re aware of two studies of nonprofit board diversity that found that diverse boards are associated with better fundraising and social performance, as well as with the use of inclusive governance practices that allow the board to incorporate community perspectives into their strategic decision making.

“During the last couple of years, NhRP has had discussions with (and received guiding documents from) Evan Wolfson of the Freedom to Marry campaign. This has been very helpful, owing to the parallels between achieving rights for nonhuman animals and achieving marriage equality.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“NhRP’s board and Directors meet once or twice per year to discuss their current activities and to talk about how these contribute to the overall aim of achieving as many rights as possible for as many animals as possible. To that end, they set short-term goals for one or five years.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“All strategic decisions at the NhRP are made by consensus, after open and evidence-based debates. This is evidence of NhRP’s understanding that having a healthy culture and satisfied employees is absolutely essential to having an effective organization.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“In the past year, NhRP has expanded their mission and they are now also active outside the courtroom.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“All strategic decisions at the NhRP are made by consensus, after open and evidence-based debates.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“When screening their film or recruiting volunteers, NhRP makes an effort to be present in all types of communities—including underserved ones. Discriminating or tailoring to a specific demographic would not only be problematic in itself, but would also be harmful to animals. In a recent court, for example, four out of five judges were women and two were Black. Every demographic group needs to be involved in the discussion of animal rights.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

Private communication with an employee of the Nonhuman Rights Project, 2017

“Does the NhRP have any revenue-generating programs? No.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“We have a handful of large donors who have been funding the NhRP for several years. The majority of our budget is from larger donors but we find that those who learn about our work tend to donate large sums, instead of small amounts.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“NhRP did not set a formal fundraising goal last year […] At the end of the year, they hired a development Director. Fundraising has never been particularly important for NhRP; they’ve never had difficulties raising the relatively small amount of money needed to run a small organization. However, the decision to pursue legislative initiatives and campaigns made it necessary to bring in a development Director and set more formal fundraising goals.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“We’re working on getting more recurring donors and have implemented new tools to make this recruitment easier.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“Within reason, staff can allocate as much time for professional development as they want. Steven Wise and Kevin Schneider not only encourage but almost mandate this, since many employees would otherwise be reluctant to take time off from their typical work. Dominguez attends conferences regularly and has never been told that he could not go to a conference or event on technology, networking, or any other topic. Part of Campaign Director Lisa Rainwater‘s job is to read books about movement building/grassroots organizations that she considers interesting.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

This year we attempted to speak confidentially with two non-leadership staff members from each comprehensively evaluated charity. To protect their confidentiality, what we learned in these conversations is paraphrased in the review, and references to these conversations are identified only as “Private communication with an employee of [Charity], 2017.” For more information, see our blog post discussing this change.

Private communication with an employee of the Nonhuman Rights Project, 2017

Private communication with an employee of the Nonhuman Rights Project, 2017

“NhRP also has a better ratio of women to men than most organizations; about half of their employees are women. While the movement consists primarily of women, few of them are in leadership positions. This is different at NhRP, where the board consists of two women and one man.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“When screening their film or recruiting volunteers, NhRP makes an effort to be present in all types of communities—including underserved ones. Discriminating or tailoring to a specific demographic would not only be problematic in itself, but would also be harmful to animals. In a recent court, for example, four out of five judges were women and two were Black.” —Conversation with Matthew Dominguez of the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

Private communication with an employee of the Nonhuman Rights Project, 2017

“Happy to report that a formal policy on harassment is being drafted by a labor law firm now and should be adopted within a few weeks. We have a policy on discrimination but that is being updated by the law firm.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

During our review process we performed Google searches wherein we paired the terms “harassment,” “discrimination,” and “lawsuit” with the names of senior members of each organization’s leadership.

“[…] the NhRP has slowly and strategically pushed these judges into a legal corner in which they must (1) rule in the NhRP’s favor as doing so vindicates the values and principles the judges themselves have long espoused, such as liberty and equality; (2) find that the judges no longer believe in those principles and values, which is unlikely, or (3) arbitrarily and/or irrationally and/or as a result of bias simply rule against the NhRP, which they have often done to date. But such decisions cannot survive as they conflict with the judicial requirement that decisions be rational, non-arbitrary, and unbiased. To the extent they are not they are unstable and liable to be overturned or not followed.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

“[…] the Tommy and Kiko court noted that: ‘Petitioner argues that the ability to acknowledge a legal duty or legal responsibility should not be determinative of entitlement to habeas relief, since, for example, infants cannot comprehend that they owe duties or responsibilities and a comatose person lacks sentience, yet both have legal rights.'” —Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)

For a non-exhaustive list of such publications, see Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017).

“In 2015, the NhRP, for the first time in history, persuaded a court (the Supreme Court of the State of New York, a trial court) to issue a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of two nonhuman animals that required their captors to come into court and give a legally sufficient ground for holding them captive.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Nonhuman Rights Project (2017)