2013 Leafleting Study

ACE coordinated a study in Fall 2013 on ten college campuses around the US and Canada that investigated the difference in effects between distributing Vegan Outreach leaflets and distributing leaflets about animal abuse unrelated to diet.

- Background

- Methodology

- Analysis

- Materials

- Cooperating Organizations

- Related Blog Posts and Press Releases

Background

Many animal advocacy organizations, including ACE’s two top charities at the time of this study, The Humane League and Vegan Outreach, conduct leafleting outreach. Additionally, ACE views leafleting as an effective way to volunteer. However, there is as yet little firm data on the effectiveness of leafleting outreach campaigns. Our analysis of leafleting as an intervention relies primarily on a single study carried out in Fall 2012 and on anecdotal evidence. While leafleting could be much less effective than our estimate while still being one of the best available ways to reduce suffering, ultimately we would like better data regarding the impacts of the interventions we recommend. With this study, we seek to partially rectify the asymmetry between our strong recommendation of leafleting as an intervention and the weak data in support of this recommendation.

Methodology

In the first phase of the study, volunteers will leaflet at each school early in the fall semester, choosing a single location on campus and a single day to distribute the leaflets. They will offer passers-by either the control leaflet or one of the leaflets believed to influence dietary choices, using the same wording and approach in either case. The volunteers will either change which kind of leaflet is offered every hour, or will have some volunteers at each site offering each leaflet, depending on specific local needs.

For the second phase of the study, a volunteer or volunteers will return to the location on each campus where leaflets were distributed on the same day of the week that the leafleting occurred, but seven to nine weeks later. They will not identify themselves as connected to the earlier leaflet team or as animal activists. These volunteers will offer passing students the chance to take a short survey and receive a small treat in exchange. The survey will consist of neutral dietary questions, followed by demographic questions and a single question asking students to identify any leaflets pictured which they received in the current school year.

After the second phase is complete at all schools, the data will be tabulated and analyzed.

Leafleting Procedures

The leaflets distributed will include Compassionate Choices and Even If You Like Meat from Vegan Outreach and The Cruelty Behind the Cuteness from the Humane Society of the United States. Since the leaflets from Vegan Outreach are substantially similar and are intended to promote veganism, vegetarianism, and reduced consumption of animal products, these will be distributed indifferently as the experimental leaflets. Since The Cruelty Behind the Cuteness portrays animal suffering in puppy mills and is not expected to cause dietary change, it will be distributed as the control leaflet.

At most schools, a single team of leafleters will choose a location and day of the week where many students will be passing along a single path to regularly visited locations such as classes. The team will hand out either control or experimental leaflets for an hour, after which they will switch to the other type of leaflet. They will continue switching types of leaflet each hour until they choose to stop. As they hand out each leaflet, they will say “Leaflet to help animals,” a phrase appropriate to either type of leaflet, so that each student is equally likely to take an experimental or control flyer and is simply taking the leaflet offered to them.

At a minority of schools, specific concerns prevent this plan from being followed in its entirety. For instance, at some schools, a paid worker will be handing out Vegan Outreach leaflets and will not be able to hand out control leaflets. In these cases, volunteers may hand out only control leaflets, so that roughly even numbers of control and experimental leaflets are distributed. The workers and volunteers will coordinate to avoid handing out both kinds of leaflet to the same student or to students in conversation, in order to avoid mixing the effects of the control and experimental leaflets.

After the leafleting has taken place, the leafleters will contact the study coordinators to report on their experience. They will tell the coordinators where and when they distributed the leaflets, how many of each type of leaflet they were able to distribute, and any alterations they made to the planned procedure.

View the instructions provided to the leafleting teams.

Survey Procedures

Surveyors will revisit the locations where leafleting took place seven to nine weeks after the leafleting on each campus. They will conduct the surveys on the same day of the week and at the same time of day as the leafleting took place, to take advantage of class schedules and maximize the number of respondents to the survey who were offered leaflets two months previously. Surveyors will not identify themselves as animal advocates or disclose the purpose of the survey to potential respondents.

Surveyors will be equipped with paper surveys, pencils, and with small incentives to offer for survey completion. They will ask passers-by to take a brief survey in return for a small treat. The survey will ask general dietary questions on one page and on a later page will show pictures of the leaflets distributed. Respondents will be asked which, if any, of the pictured leaflets they received on campus during the current school year.

View the instructions for surveyors.

View the survey and flyer selection sheet.

View the full study protocol.

Analysis

Survey respondents who report having received either Vegan Outreach leaflet, even if they report also having received the control leaflet, will be considered part of the experimental group. Respondents who report only having received the control leaflet will be considered part of the control group. Respondents who do not report having received any leaflet we distributed will not be considered part of either group.

The primary goal of analysis will be to determine whether rates of conversion to vegetarianism and veganism during the study period are higher among subjects in the experimental group than among subjects in the control group. Depending on the final survey design, the analysis may also consider whether respondents in the experimental group have reduced their rates of meat and animal product consumption more than respondents in the control group, even among those respondents who do consume these products at the time of the survey.

Materials

Official Protocol

Instructions to Leafleters

Instructions to Surveyors

Compassionate Choices Leaflet

Even If You Like Meat Leaflet

The Cruelty Behind the Cuteness Leaflet

Survey and Flyer Selection Sheet

Dataset

Dataset Interpretation Guide

Cooperating Organizations

Compassionate Action For Animals

Mercy For Animals

The Humane League

Vegan Outreach

Related Blog Posts and Press Releases

Breaking down the leafleting study

Leafleting Study Analysis

This page presents an analysis of the results of ACE’s 2013 study on leafleting, prepared by ACE staff with help from Statistics Without Borders. See the study design page for more details about the methodology of the study.

Pre-analysis Plan

“Survey respondents who report having received either Vegan Outreach leaflet, even if they report also having received the control leaflet, will be considered part of the experimental group. Respondents who report only having received the control leaflet will be considered part of the control group. Respondents who do not report having received any leaflet we distributed will not be considered part of either group.

The primary goal of analysis will be to determine whether rates of conversion to vegetarianism and veganism during the study period are higher among subjects in the experimental group than among subjects in the control group. Depending on the final survey design, the analysis may also consider whether respondents in the experimental group have reduced their rates of meat and animal product consumption more than respondents in the control group, even among those respondents who do consume these products at the time of the survey.”

Main Results

Assignment of Experimental and Control Groups

Our study design required subjects to identify which flyers they had received during the study period, if any, so that we could assign them to experimental or control groups as appropriate. Subjects were shown images of several flyers and asked to indicate any that they had received. The flyers shown included:

- Two Vegan Outreach flyers, one of which we distributed at each school

- The back of one of these flyers, because the flyers were distributed with this side facing upwards at one school

- The control flyer about puppy mills

- A fictional flyer with a picture of a cat.

Subjects were also able to respond that they were unsure which flyers they had received or that they had not received any flyers.

Our original plan was to assign subjects to the experimental group if they reported receiving the Vegan Outreach leaflet that we distributed at their school, regardless of which other leaflets they reported receiving, and the control group if they reported receiving the control flyer and had not been assigned to the experimental group. Because our volunteers tried to distribute similar numbers of both types of flyer, we expected the control group to be smaller than the experimental group, but not very much smaller. We expected to have a large number of subjects assigned to neither group.

The actual group assignments differed from our expectations, with 123 participants in the experimental group, 23 in the control group, and 477 in neither group. Of the participants assigned to the experimental group, 21 reported receiving the control flyer. Additionally, 101 participants spread throughout all groups reported receiving flyers we did not distribute at their location. We discuss these participants in more detail below.

While our further analysis takes the originally designated control group into account where possible, we also used the group that received neither flyer as a control. The extremely small number of people who reported receiving only the control flyer means that no reasonably probable effect of leafleting would produce statistically significant results when compared to that control group. To better gauge which of our results were meaningful, we used the larger control group despite our concerns that this group would not be as well-balanced against the experimental group in characteristics besides which flyer they had received.

Conversion to Vegetarianism and Veganism

Because previous studies have found that many people who self-report that they are vegetarian also report recently having eaten meat, we measure conversion rates to vegetarianism and veganism by the number of people who reported that they had stopped consuming specific types of animal products. A summary of those results is available in the table below. Percentages are taken out of the number of participants in each group who responded to both questions about a particular food item, which vary by item and in general are slightly smaller than the total group sizes given in the previous section.

| experimental | control | no leaflet | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| red meat | stopped eating | 7 | 0 | 6 |

| started eating | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| net change | 7 | 0 | -1 | |

| net change (%) | 6% | 0% | 0% | |

| poultry | stopped eating | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| started eating | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| net change | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| net change (%) | 4% | 0% | 0% | |

| fish | stopped eating | 3 | 0 | 12 |

| started eating | 2 | 1 | 4 | |

| net change | 1 | -1 | 8 | |

| net change (%) | 1% | -5% | 2% | |

| eggs | stopped eating | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| started eating | 2 | 0 | 6 | |

| net change | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| net change (%) | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| dairy | stopped eating | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| started eating | 3 | 0 | 4 | |

| net change | -2 | 0 | 0 | |

| net change (%) | -2% | 0% | 0% | |

Because of the small absolute numbers of people who started or stopped eating the products in questions, not all these differences are meaningful. Using a generalized linear model and chi-square test, the differences in change of consumption of red meat and poultry (but not fish) between the experimental group and the group that received no flyer were statistically significant (p = 0.0014 and p = 0.0085 respectively). Comparisons between the experimental group and the group that received the control flyer were not statistically significant for red meat, poultry, or fish. We did not run this test on the data regarding eggs or dairy, but we believe that these differences would also not be statistically significant.

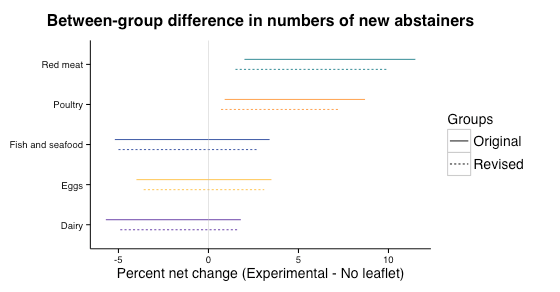

We generated 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the difference in percent net change between the experimental group and the group who received no flyers for each animal product. Positive differences indicate that a higher percentage of subjects in the experimental group quit eating a product than in the no-flyer group. The confidence intervals for red meat and poultry were (2.0%, 11.5%) and (0.9%, 8.7%) respectively. These were the only intervals that did not contain 0; the intervals for fish, eggs, and dairy were (-5.2%, 3.4%), (-4.0%, 3.5%), and (-5.7%, 1.8%) respectively.

Meat Reduction

We also considered overall reduction or increase in meat consumption throughout the sample. We were less certain that the results of this analysis would correspond neatly with reality, because it is more difficult for respondents to remember how often they eat a type of food than whether they eat it at all. However, previous studies had found large numbers of respondents reporting that they had decreased but not eliminated consumption of certain animal products. In our sample, the population overall reported decreasing meat consumption over the three month study period, but that decrease was not significantly associated with the leaflet received. We did not analyze reduction in dairy and egg consumption, which we would expect to be more difficult to interpret in part because eggs and dairy are often present in food in non-obvious ways.

We analyzed meat reduction in two ways. The first categorized respondents’ consumption of red meat, poultry, and fish as having increased, decreased, or stayed the same over the three months, using the frequencies respondents reported for their consumption at the start and end of the three month period. In the sample as a whole, fewer reported increasing than decreasing how often they ate red meat (17% and 21%), poultry (16% and 19%), and fish (10%, 22%). However, chi square tests did not find that the experimental group differed from the other groups in the proportion of people who had increased or decreased consumption of any of these types of meat.

Even if the number of people who increased or decreased their meat consumption did not depend on the leaflet received, it might be the case that people who receive leaflets decrease their consumption by more than people who do not. Our second analysis addressed this possibility by considering the size of the change each respondent reported, in number of times per week a food was consumed. Our models did not find a significant effect of the leaflet received in predicting change in number of times per week an individual consumed red meat, poultry, fish, or all of these meats combined.

Additional Results

Respondent Characteristics

Our sample was reasonably representative of the audience targeted by many leafleting groups, with 57% of respondents being female and the median age being 21 years. There was no significant association between flyer received and age or gender.

Respondents in our study were asked both to describe their diet and to indicate the frequency with which they ate specific foods. As in other samples, a substantial percentage (45%) of those who indicated that they were vegetarian or vegan also reported consuming some type of meat.

Social Desirability

Our survey included a social desirability instrument, the RAND SDRS-5. Respondents who score high on such an instrument are believed to be generally more likely to be answering questions according to what they feel is socially desirable or socially acceptable than respondents who score lower. Accordingly, if responses on another item are correlated with social desirability scores, Researchers must consider the possibility that some respondents have provided desirable rather than truthful responses to that item.

In our sample, social desirability scores were on average higher for women and tended to increase with age. In the experimental group, a higher social desirability score was also correlated with a larger decrease in the frequency of meat consumption (all types combined). There were also statistically significant differences between the experimental group and the no-flyer group in the association between frequency of meat consumption and social desirability score for every type of meat except fish alone. These findings suggest that social desirability does play a role in reported meat consumption, especially for respondents who have been exposed to vegan outreach materials. Care should be taken to minimize and track its effects.

More About Group Assignment

We had two concerns about group assignments once we tabulated the data. First, because our intended control group was so small, we needed to consider to what extent the larger no-flyer group is an appropriate substitute. As discussed above, it did not differ significantly in age or gender from the experimental group, which is helpful because age and gender have both been found to correlate with vegetarianism in the past, and theoretically they should also correlate with openness towards diet change and willingness to take a leaflet. The no-flyer group and the experimental group did show different associations between social desirability and responses to diet questions, but it is not clear whether this should be taken to be an effect that would precede or follow acceptance of a flyer.

One set of measurable variables that should have preceded acceptance of a flyer is responses to diet questions about the start of the study period. If the experimental group were more sympathetic to animals before the study started than the no-flyer group was, we might expect to see higher rates of vegetarianism or veganism among them at that time. In the table below we show the percentages of respondents who reported that they never ate each of the products at the start of the study period (three months before the survey took place). These provide some reassurance that the groups were not extremely different in composition, but of course cannot completely resolve all concerns.

| experimental | no leaflet | |

|---|---|---|

| red meat | 11% | 11% |

| poultry | 8% | 7% |

| fish and seafood | 17% | 13% |

| eggs | 8% | 4% |

| dairy | 9% | 4% |

We also had concerns about respondents’ recall of which flyer they received, given the many respondents who reported receiving flyers we did not think they would have received. Using the Adopt a College website, we searched for distributions of Vegan Outreach leaflets that might explain this pattern. We found such distributions at two schools, and when they were accounted for, 61 of the confusing responses remained. Five of the subjects reported receiving the completely fictional flyer, and based on this we believe that many of the other respondents may also have been erroneously reporting which flyer they received, including some whom we classed in the experimental group. This is especially a concern because after taking a survey about diet, we would expect respondents to be more likely to mistakenly report that they had received a flyer with a picture of a farm animal than one with a picture of a cat. Also, respondents who really received a flyer in a previous semester may have been more likely to report receiving that flyer than to report receiving a flyer they had never seen before. We aren’t sure how best to deal with these concerns.

We did not re-run the full analysis with the new experimental, control, and no-flyer groups based on what we found on Adopt a College. Running multiple analyses of the same data can lead to problems differentiating true effects from effects that appear by chance when many tests are performed. Also, we don’t know whether the distributions by other groups occurred at the same sites and time of week as our leafleting and surveying did, which could affect whether it was plausible for subjects to have received a leaflet, even if it was handed out on their campus. However, to get a sense of how much this would change our analysis, we recalculated the set of confidence intervals for difference in percentage of respondents who stopped eating animal products. The new intervals were: for red meat, (1.5%, 10.0%); for poultry, (0.7%, 7.3%); for fish, (-5.0%, 2.7%); for eggs, (-3.6%, 3.1%); and for dairy, (-4.9%, 1.7%).

Conclusions

We found support for claims that distributing leaflets from Vegan Outreach (or similar leaflets published by other groups) causes a small percentage of respondents to go vegetarian or give up eating specific types of meat. Our study showed surprisingly large effect sizes for respondents giving up red meat and poultry with respect to previous work, and a surprisingly small effect size for respondents giving up fish and seafood. Because our sample of respondents who reported receiving a leaflet was smaller than that in, for example, the study conducted by The Humane League and Farm Sanctuary, our effect sizes are likely to vary more from the true effect size. In that study, the effect sizes ranged from about 1% giving up fish to about 3% giving up red meat. Looking at the two studies together, our study suggests that the effects they found on people giving up red meat and poultry are in fact effects of the leaflets, but effects on fish, egg, and dairy consumption may not be. Because the experimental group in the earlier study was much larger than the experimental group in this study, we do not think the true effects of leafleting in terms of people giving up red meat or poultry are as large as those found in this study; the earlier, lower estimates are probably more accurate. On the other hand, where our study found smaller effect sizes or no effect, our findings reinforce concerns about the previous study’s design.

We did not find support for claims that distributing leaflets from Vegan Outreach (or similar leaflets published by other groups) causes the overall population who receives the leaflets to reduce their meat consumption. Rather, we found an overall pattern of reported reduction in meat consumption throughout the sample. We do not know whether this pattern reflects real decreases in consumption or only systematic errors in recollection. College students may in general be trying to reduce their meat consumption, or they may be reporting different consumption in the past than the present for some other reason. These findings suggest that studies without control groups may find or have found reductions in meat consumption that should not properly be attributed to the intervention being studied, at least in their entirety.

In addition to this finding reinforcing the importance of control groups, we found signs that self-reported exposure to interventions is not always accurate and that social desirability bias does operate on reported meat consumption in ways that interact with exposure to interventions. These findings impose caution on our interpretations of the results of this study. They also underscore the importance of careful study design more generally.

Resources

Survey and Flyer Selection Sheet

Full Dataset

Dataset Interpretation Guide

Statistical Reports (.zip file)

Materials

Official Protocol

Instructions to Leafleters

Instructions to Surveyors

Compassionate Choices Leaflet

Even If You Like Meat Leaflet

The Cruelty Behind the Cuteness Leaflet

Survey and Flyer Selection Sheet

Dataset

Dataset Interpretation Guide

Cooperating Organizations

Compassionate Action For Animals

Mercy For Animals

The Humane League

Vegan Outreach

Related Blog Posts and Press Releases

Breaking down the leafleting study

Leafleting Study Analysis

Resources

Survey and Flyer Selection Sheet

Full Dataset

Dataset Interpretation Guide

Statistical Reports (.zip file)