The Good Food Institute

Archived Review| Review Published: | December, 2019 |

| Current Version | 2022 |

Archived Version: December, 2019

What does The Good Food Institute do?

The Good Food Institute (GFI), which is headquartered in the U.S., works to transform the animal agriculture industry by promoting the development of competitive alternatives to animal-based meat, dairy, and eggs. GFI seeks out entrepreneurs and scientists to join or form start-ups in the plant-based and cell-cultured meat (i.e., meat grown in a culture without animal slaughter, also called cell-based meat, clean meat, and cultivated meat1) market sectors. They provide business, legal, scientific, and strategic guidance for plant-based and cellular product companies. They also engage in regulatory and statutory policy work to level the playing field for plant-based and cell-cultured products in the consumer market. GFI builds relationships with food processing companies (e.g., Tyson, ADM), chain restaurants, grocery stores, and foodservice companies to improve and promote cell-cultured and plant-based alternatives to animal products. Finally, GFI works with grant-making institutions, universities, corporations, and governments to mobilize resources for research in plant-based and cell-cultured meat.

What are their strengths?

We believe that developing competitive alternatives to animal products could have an enormous impact for farmed animals in the long term. It could cause consumers to purchase fewer animal products and it might do so much more quickly than using moral arguments to persuade consumers to stop eating meat, dairy, and eggs. We feel confident in GFI’s leadership and strategic vision. They are focused on effectiveness and seem determined to maximize the efficiency of their operations and the impact of their work. GFI has established five international subsidiaries, and we expect this kind of international advocacy to be important to ensure the adoption of plant-based, and especially cell-cultured, meat worldwide. We suspect that GFI’s approach to fundraising has a relatively high expected effectiveness, especially considering their efforts may effectively increase the capacity of the movement by building connections with and sourcing funding from other movements. Our impression, from a variety of sources, is that GFI has been involved in one way or another in a large portion of the major developments in the plant-based and cell-cultured meat sectors since their founding.

What are their weaknesses?

GFI’s track record does not yet include some of the outcomes they most hope to accomplish, e.g., the successful development of cell-cultured meat, dairy, and eggs. In addition, while they have provided background information for policy makers in India, the U.K, and Singapore, no legal regulatory frameworks for cell-cultured meat have been adopted thus far. We are uncertain about the long-term impacts of these programs, since we expect that it will take some time—perhaps decades—to develop cell-cultured meat that can compete commercially with conventional meat. GFI has had more short-term success in helping companies develop and market plant-based alternatives to meat. They have also had success in working with grocery stores to increase the availability and improve the marketing of plant-based options, but we are still somewhat uncertain what would have happened in these cases had GFI not been involved.

Internally, GFI has been expanding quite quickly. Since the organization is hiring and building their infrastructure concurrently with their primary programs, we are somewhat concerned about the workload of some of their staff members. We also have some concerns regarding GFI’s Board of Directors, which may lack sufficient independence from GFI’s team, potentially lacks a diversity of viewpoints, and does not have term limits.

Why did GFI receive our top recommendation?

Animal advocates have been working for decades to weaken the animal agriculture industry by encouraging individuals and institutions to reduce the demand for animal products and implement humane reforms. We are happy to support the effective implementation of those interventions, but we also believe that engaging in a wider range of promising tactics may increase the animal advocacy movement’s chance of success. Developing and promoting attractive alternatives to animal products seems like a promising way to transform the animal agriculture industry. There are few charities working in this area, and GFI has shown strong leadership and efficiency.

How much money could they use?

We estimate that GFI’s plans for expansion would cost $1.4 million to $4.7 million. This number does not take into account potential increases or decreases in revenue. We estimate that GFI could use an additional $1.0 to $5.0 million for research grants. We expect they would use additional funding to hire new U.S. and non-U.S. staff; expand their programs in science and technology, policy, and corporate engagement; continue their research grant program; replenish their operating reserves; and to scale their organizational infrastructure (executive, operations, communications, and development).

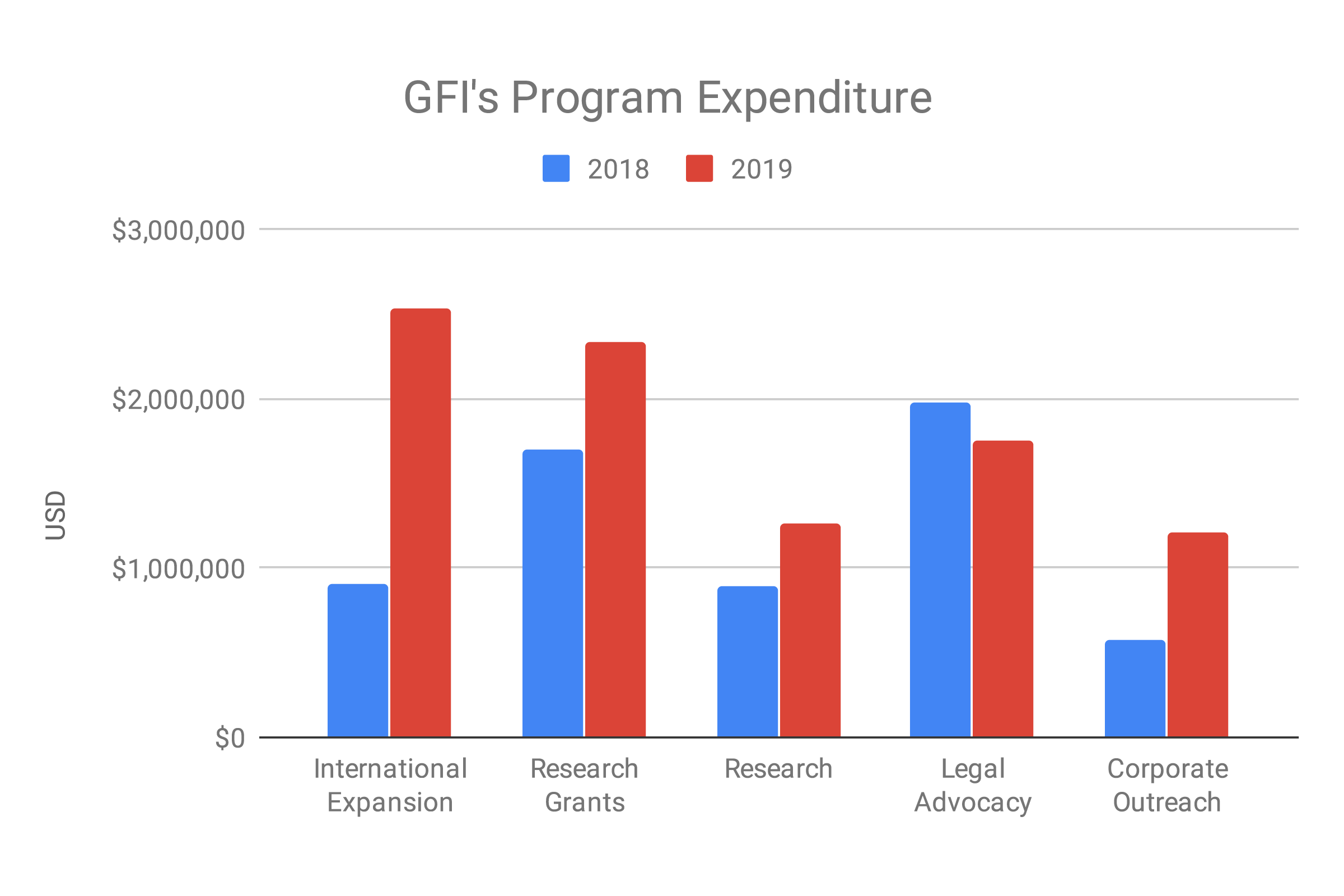

What do you get for your donation?

Your donation supports GFI’s programs to make progress on the development of plant-based and cell-cultured meat technologies. From an average $1,000 donation, GFI would spend about $278 on international expansion, $257 on research grants, $192 on legal advocacy, $138 on research, and $134 on corporate outreach.

The impact that donations to GFI have for farmed animals is more speculative and long term than the impact of donations to one of our other Top Charities. Given the speculative nature of GFI’s impact on farmed animals, we currently have not completed a cost-effectiveness estimate for donations to them. Still, we think donations to GFI have quite high expected value.

If GFI raises additional funds beyond what they’ve budgeted for this year, they plan to hire more staff to grow their international teams from 20 to roughly 40 staff in 2020. They would hire more science, policy, and support staff in Israel, Asia Pacrific, Europe, India, and Brazil.

The Good Food Institute has been one of our Top Charities since November 2016.

The Good Food Institute supports the use of the term “cultivated meat.” For more information, see Friedrich (2019).

Table of Contents

- How The Good Food Institute Performs on our Criteria

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Questions for Further Consideration

- Supplemental Materials

How The Good Food Institute Performs on our Criteria

Interpreting our “Overall Assessments”

We provide an overall assessment of each charity’s performance on each criterion. These assessments are expressed as two series of circles:

The number of teal circles represents our assessment of a charity’s performance on a given criterion relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated.

| A single circle indicates that a charity’s performance is weak on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated: | |

| Two circles indicate that a charity’s performance is average on a given criterion, relative to other charities we’ve evaluated: | |

| Three circles indicate that a charity’s performance is strong on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated: |

The number of gray circles indicates the strength of the evidence supporting each performance assessment and, correspondingly, our confidence in each assessment:

| Low confidence: Very limited evidence is available pertaining to the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to other charities. The evidence that is available may be low quality or difficult to verify. | |

| Moderate confidence: There is evidence supporting our conclusion, and at least some of it is high quality and/or verified with third-party sources. | |

| High confidence: There is substantial high-quality evidence supporting the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to other charities. There may be randomized controlled trials supporting the effectiveness of the charity’s programs and/or multiple third-party sources confirming the charity’s accomplishments.1 |

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Overall Assessment:

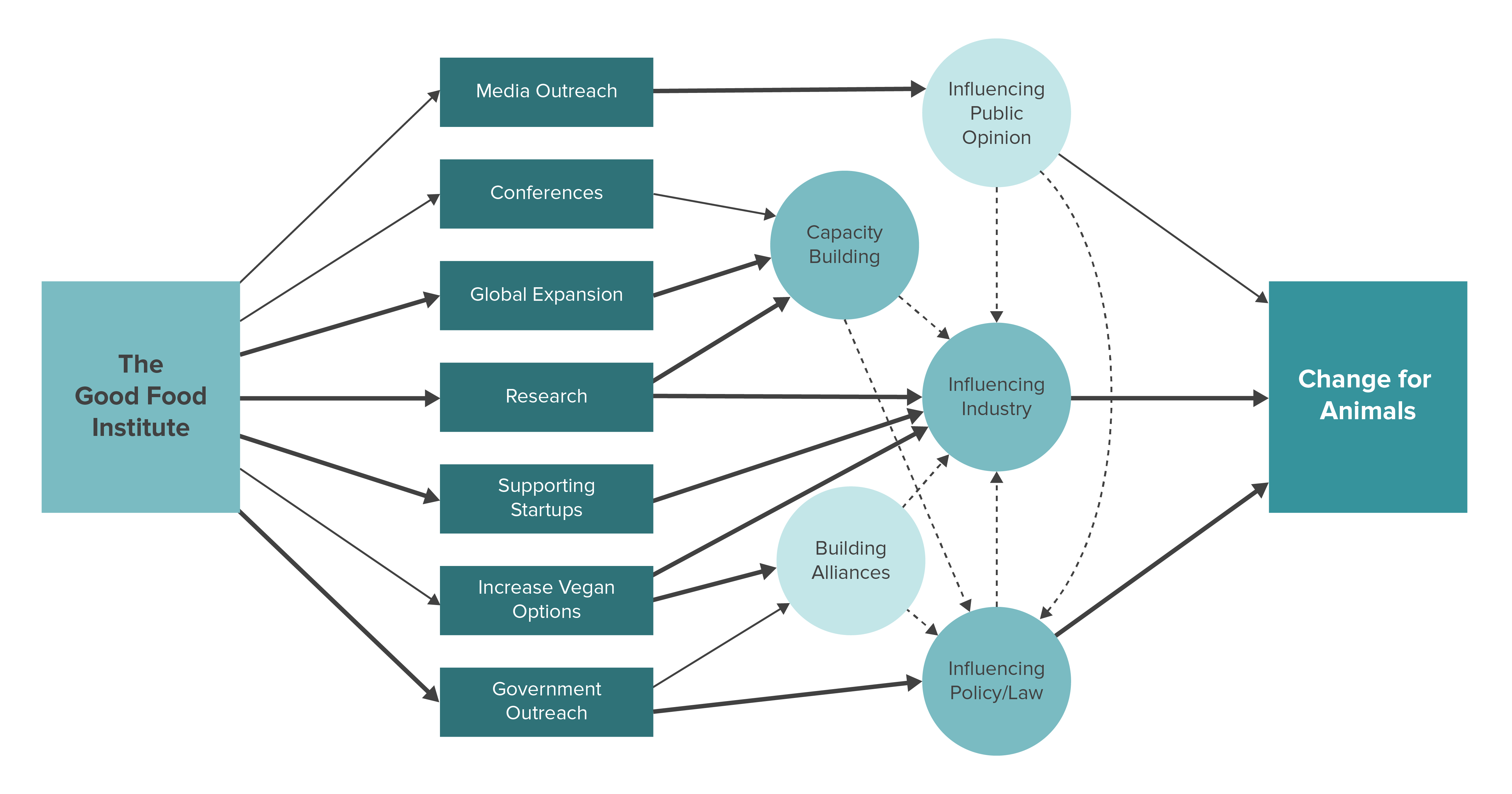

When we begin our evaluation process, we consider whether each charity is working in high-impact cause areas and employing effective interventions that are likely to produce positive outcomes for animals. These outcomes tend to fall under at least one of the following categories described in our Menu of Outcomes for Animal Advocacy. These categories are: influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

Cause Area

The Good Food Institute focuses exclusively on promoting and supporting the development of cell-cultured and plant-based meat, which will benefit farmed animals. We think farmed animal advocacy is a high-impact cause area.

Theory of Change

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

A note about long-term impact

We do represent some of each charity’s long-term impact in our theory of change diagrams, though we are generally much less certain about the long-term impact of a charity or intervention than we are about more short-term impact. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew towards overemphasizing short-term impact. Nevertheless, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most. The potential number of individuals affected increases over time due to both human and animal population growth as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Interventions and Projected Outcomes

The Good Food Institute pursues many different avenues for creating change for animals: They work to influence public opinion, build the capacity of the movement, influence industry, build alliances, and influence policy and the law. Below, we describe the work that they do in each area, listed roughly in order of the financial resources they devote to each area (from highest to lowest).

Capacity building

Working to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement can have far-reaching impact. While capacity-building projects may not always help animals directly, they can help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Our recent research on the way that resources are allocated between different animal advocacy interventions suggests that capacity building is currently neglected relative to other outcomes such as influencing public opinion and industry. GFI’s capacity-building work includes engaging in research, grantmaking, and outreach on college campuses, as well as aiming to redirect funds from other causes to animal advocacy.

GFI has helped contribute to the development of foundational knowledge necessary for the growth of plant-based and cell-cultured meat production. They have done this directly by publishing scientific white papers and consumer research, and by hosting and presenting their findings at conferences. They have also contributed indirectly by working to advance research and development in the field more generally. GFI recently launched their Competitive Research Grant Program, which awards open-access plant-based and cell-cultured meat research funding to top scientists. Developing inexpensive, nutritious, and appealing meat alternatives may make individuals more willing to reduce their meat consumption.

As part of their work to recruit students, scientists, and entrepreneurs to work in cellular agriculture and plant-based technology, GFI contributed to the development of the first university course in plant-based meat2 and the Alternative Meats Lab, both at UC Berkeley. Through collaboration with the Cellular Agriculture Society (CAS), they also helped to develop a course on plant-based and cultured meat at Stanford, which one of GFI’s scientists was teaching, though the course has since been discontinued due to CAS’s deprioritization of all projects aside from media creation.3, 4 The course at UC Berkeley is a competition-based lab within an entrepreneurial program, while the course at Stanford was a more traditional format within their science department. GFI also launched the first plant-based and cell-cultured meat MOOC (massive open online course). While we think the development of such courses and research centers is promising since they plausibly provide additional entry points for people to get involved in the field, we’re generally unsure about the marginal impact of efforts to recruit students and scientists to work in food technology.

GFI is headquartered in the U.S., and they have established affiliates in Brazil, India, Israel, Asia-Pacific, and Europe. While relatively new, their affiliates pursue the same goals that GFI does: media outreach; consumer and marketing research; funding cell-cultured meat research; influencing plant-based and cell-cultured egg, dairy, and meat development; supporting entrepreneurs and startups in the plant-based and cell-cultured meat, eggs, and dairy space; and influencing policy related to plant-based and cell-cultured eggs, dairy, and meat. One of their primary goals for the next two years is ensuring each international affiliate is fully operational and independent.5 We expect international advocacy for cell-cultured meat to be important to ensure that it is adopted worldwide.

We also consider some of GFI’s fundraising activities to be capacity building, in part because they build connections across movements. Whereas many animal charities draw funds primarily from within the movement (e.g., from donors who might have otherwise given to other animal charities), GFI is also seeking to reach potential donors whose primary interests are in environmental protection, the sustainability of the global food system, and human health.6 GFI also works to convince academic institutions, government agencies,7 and other major funders8 to invest in alternatives to animal products. In contrast to securing funding from donors who might have donated to another organization in the area of animal advocacy, some of these funds would probably not have otherwise been used to help animals. In this way, GFI’s fundraising activities might be more effective than other animal charities’ fundraising activities at building the capacity of the movement.

Influencing policy and the law

GFI conducts legislative advocacy and lobbying with the goal of bringing plant-based and cell-cultured meat to market. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects to be particularly long-lasting.

GFI works to influence government policies and laws by engaging in outreach with elected officials and their staffs, writing op-eds and white papers, filing lawsuits and amicus briefs, and lobbying for plant-based and cell-cultured meat. Some of this work aims to shift spending from research on animal agriculture to research on plant-based proteins, while other efforts oppose laws which would criminalize plant-based and cell-cultured meat, eggs, and dairy being referred to as meat, eggs, and dairy. The immediate impact on animals of much of this work is limited. However, advances in plant-based and cell-cultured product development may be able to have a larger impact to the extent that they are successful. The ultimate impact of much of this work is contingent on GFI and their allies successfully staying ahead of the much larger meat and dairy industries, and on the progress of the plant-based and cell-cultured meat industry more generally.

GFI is also working to clear regulatory hurdles and to ensure a clear path to market for cell-cultured meat both in the U.S. and internationally. They have worked to actively shape the American regulatory framework for cell-cultured meat and have begun efforts in India, the United Kingdom, and Singapore. Since there are not many groups working towards favorable policies supporting plant-based and cell-cultured foods, we are uncertain about the tractability of this work—we expect it to be possible to negotiate beneficial regulatory frameworks, but we are uncertain how many resources it will require. However, given that GFI is one of only two groups we are currently aware of working in this neglected area in the U.S.,9 there is potential for this to be a high-impact strategy.

Influencing industry

The Good Food Institute works with corporations to distribute and market plant-based products and encourage the development of plant-based and/or cell-cultured products. In the short to medium term, influencing industries to develop and distribute alternatives to animal products can create change for a larger number of animals than individual outreach can with the same amount of resources. It also seems more tractable to secure systemic change one corporation at a time rather than lobbying for larger-scale legislative change. Though the long-term effects of corporate outreach are yet to be seen, we believe that these interventions have a high potential to be impactful when implemented thoughtfully. In particular, successfully increasing the quality and availability of cell-cultured and plant-based foods may help to create a climate in which it’s easier for individuals to reduce their use of animal products. Plant-based milk, for example, is already showing a tendency to displace the sales of conventional milk in the U.S.10

GFI provides strategic and technical support to over 100 plant-based and cell-cultured meat entrepreneurs. They provide fundraising strategy, conduct technical due diligence, facilitate connections and identify funding opportunities for startups, and bring plant-based and cell-cultured meat science to professional and academic conferences. In 2018, they created a step-by-step guide to founding a plant-based or cell-cultured meat company to enable interested entrepreneurs to found companies, which won an award from Fast Company magazine. GFI also conducts literature reviews and writes white papers to consolidate and disseminate knowledge throughout the field, as well as performs its own market research. They aim to effectively funnel funding to where it will be most impactful by (i) conducting research to identify areas ready for investment and success and (ii) meeting with venture capital groups and large meat companies to direct funding to these opportunities in cell-cultured and plant-based meat.

Another avenue for impact is through GFI’s work in corporate outreach within the animal agriculture industry and the consumer market. GFI collaborates with large meat and food companies and consumer packaged goods companies to encourage them to transition to plant-based food and aim to alter the consumer landscape by working with large restaurant chains to increase plant-based offerings. One piece of this work has been the creation of a scorecard of the largest 100 restaurant chains that ranks them according to their availability of plant-based options. They are also working with grocery stores to increase the availability of plant-based options and to improve the marketing for them. This may have a more immediate impact on animals than their work to support the development of cell-cultured products which have yet to come to market.

Building alliances

GFI’s outreach to key influencers provides an avenue for high-impact work, since it can involve convincing a few powerful people to make decisions that could influence the lives of millions of animals. We believe that the impact of building alliances varies considerably depending on who the key influencers are and the kinds of decisions they can make.

GFI works with many key influencers. GFI encourages and facilitates collaboration within the plant-based and cell-cultured meat industry by bringing together cell-cultured meat companies from around the world quarterly and by hosting a monthly call with approximately 60 entrepreneurs as well as a Slack group with over 350 entrepreneurs.11 Increasing cooperation among the various players in the plant-based and cell-cultured meat sector could potentially accelerate growth. This may eventually help to level the playing field with the much larger and more developed animal agriculture industry.

Since 2017, GFI has provided an overview of the plant-based and cell-cultured meat, dairy, and egg space to over two hundred food and life science companies. They have engaged eight of the world’s largest meat companies and helped drive plant-based meat innovation at four of them, including speaking at one company’s annual board meeting and another company’s strategy meeting for top executives and board members. GFI’s strategy involves trying to convince the largest meat producing companies in the world to view the growing demand for plant-based and cell-cultured foods as an opportunity for transformation rather than as a disruption they would have to fight.12 Beyond working directly with corporations, GFI also lobbies Congress,13 the USDA, and the FDA14 for decisions that could have far-reaching impact—these groups can make changes on a national scale within the United States. Taken all together, GFI’s work to build alliances with large food companies and key influencers has the potential for large-scale and far-reaching impact.

Influencing public opinion

Although it is not their primary focus, the Good Food Institute works to influence individuals to adopt more animal-friendly behaviors by improving public perceptions of plant-based and cell-cultured products and encouraging their consumption through media outreach. The effects of public outreach are particularly difficult to measure for at least two important reasons. First, most studies of the effects of public outreach have been conducted on interventions that are very different from the work GFI does, and they tend to rely on self-reported data, which is generally unreliable.15 Second, even if we understood the effects of public outreach on individuals’ behavior, we still know very little about how animals are impacted by individuals engaging in behaviors such as changing their diet, deciding to vote for animal friendly laws, or becoming activists. Despite the uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of most public outreach interventions, we do think it’s important for the animal advocacy movement to target at least some outreach toward individuals. A shift in public attitudes and consumer preferences could help drive industry changes and lead to greater support for more animal-friendly policies; in fact, it might be a necessary precursor to more systemic change. On the whole, however, we believe that efforts to influence public opinion are much less neglected than other types of interventions as we describe in our Allocation of Movement Resources report.

While GFI isn’t primarily focused on influencing public opinion, they likely have some impact through their media outreach. GFI has been proactive about building relationships with the media by providing information about cell-cultured and plant-based meat as well as writing op-eds and participating in news features.16 This work has not been limited to scientific or technical outlets but rather has been aimed at mainstream audiences in an effort to get plant-based and cell-cultured meat discussions into the public eye. While the impact of this work on consumer attitudes remains to be seen, it does seem that increasing the awareness of the existence and benefits of cell-cultured and plant-based meat is a logical first step towards shifting consumer preferences.

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

Overall Assessment:

We look to recommend charities that are not just high impact, but also have room to grow. Since a recommendation from us can lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding, we look for evidence that the charity will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. We consider whether there are any non-monetary barriers to the charity’s growth, such as time or talent shortages. To do this, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. We also consider the charity’s existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential areas for growth and expansion.

Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. We check in with each of our Top Charities mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented below to indicate whether we still expect them to effectively absorb additional funding at that point.

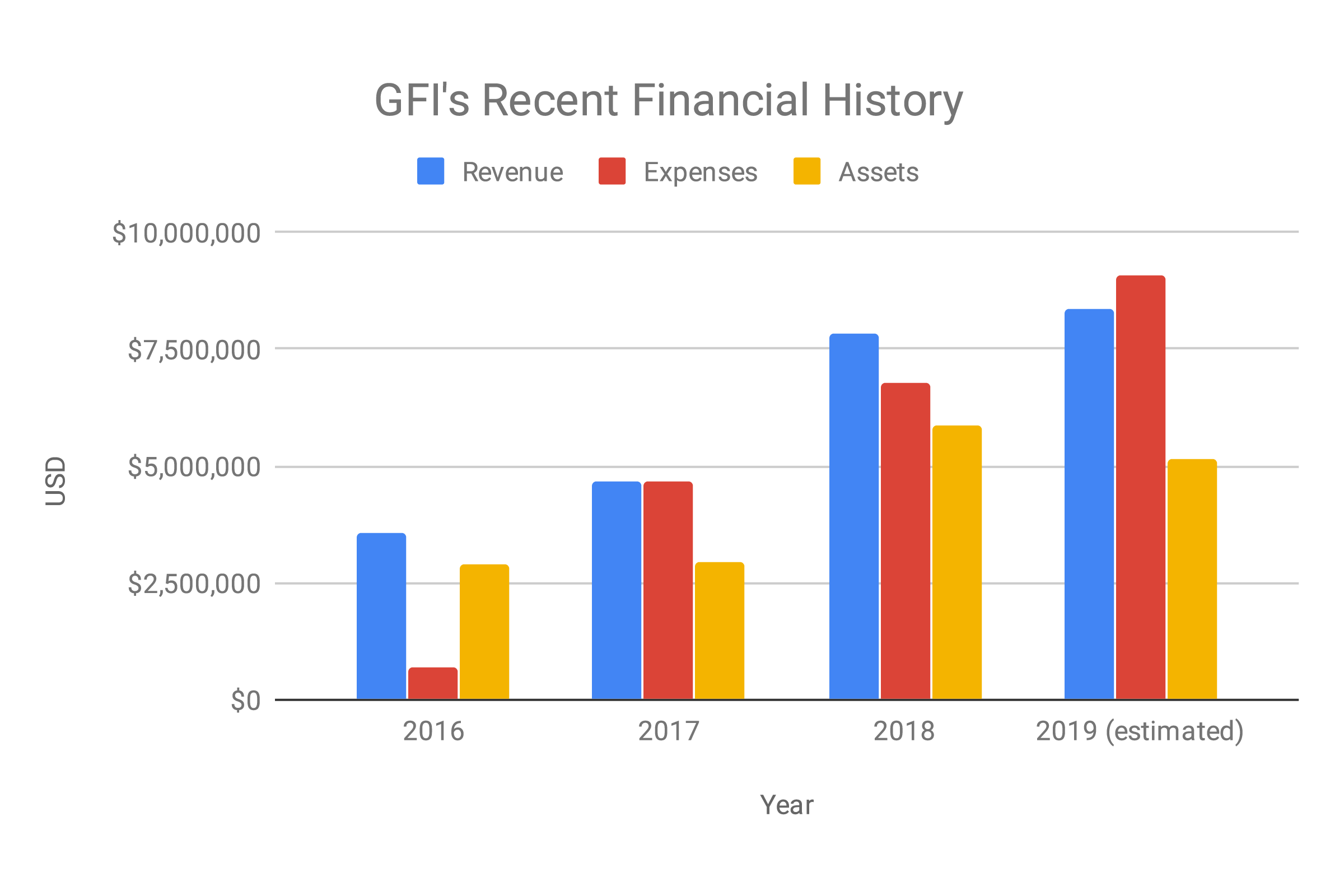

Recent Financial History

The following chart shows GFI’s recent revenue, assets,17 and expenses.18, 19 In this chart, the 2019 revenue and expenses are estimated based on the financials of the first six months of 2019.20 GFI notes that they would like to grow their reserves to cover 10–12 months of their operating budget. Part of their ability to grow depends on a pending grant decision from the Open Philanthropy Project, which previously awarded $1.0M to GFI in 2017. GFI’s fundraising budget in 2019 is $9M for core programs and $5M for the Competitive Grant Research Program.21

Estimated Future Expenses

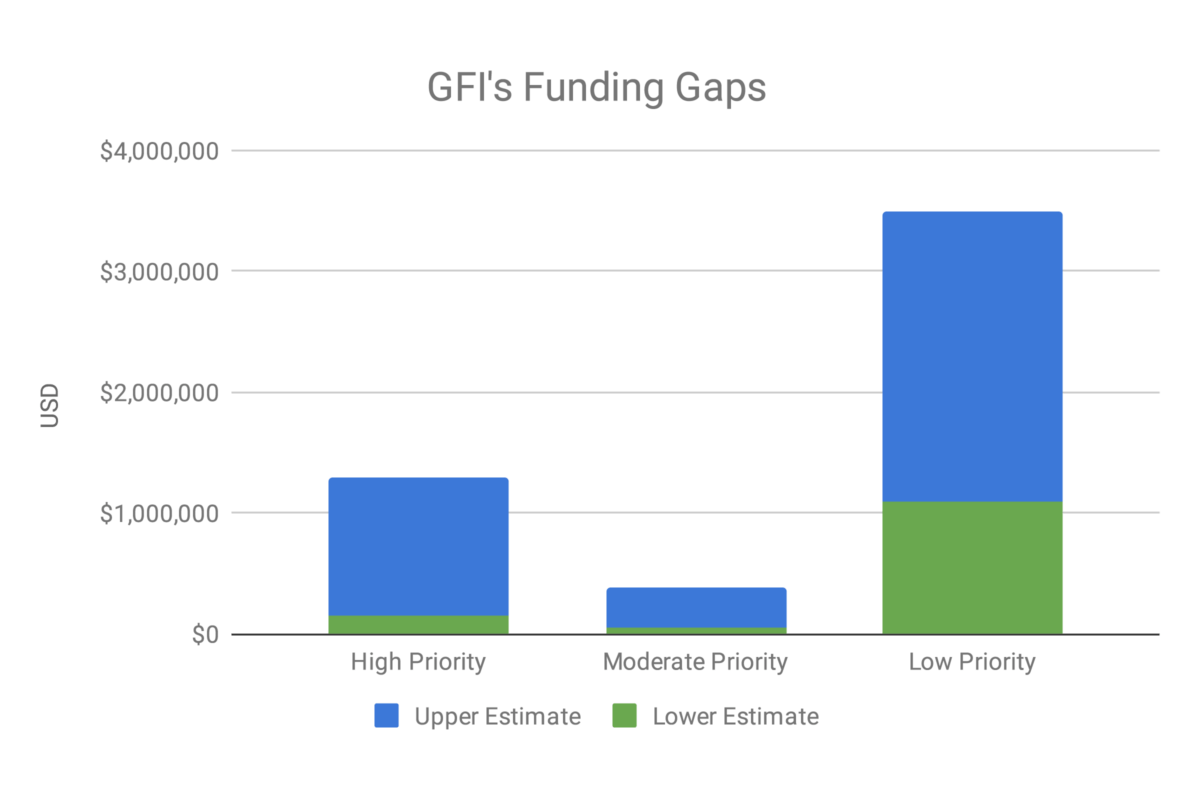

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area likely varies in its cost-effectiveness. In order to evaluate room for more funding over three priority levels, we consider each charity’s estimated future expenses,22 our assessment of the effectiveness23 of each future expense, and the feasibility of meeting each expense if more funding were provided.24

| Estimated future expense | Funding estimate | Priority level |

|---|---|---|

| Hiring 6.4 to 17 new US staff members25 | $0.16M to $1.4M26 | High (38%), moderate (31%), and low (31%) |

| Hiring 11 to 29 new non-U.S. staff members27 | $78k to $0.98M28 | High (38%), moderate (31%), and low (31%) |

| Competitive Research Grant Program29 | $1.0M to $5.0M30 | High |

| Funding to replenish reserves31 | $0.71M to $0.87M | Low |

| Possible additional expenditures32 | $0.12M to $2.5M | Low |

Estimated Room for More Funding

The cost of GFI’s plans for expansion over the three priority levels is estimated via Guesstimate and visualized in the chart above. We estimate that GFI’s plans for expansion would cost between $1.4M and $4.7M.33 Our room for more funding estimates include a linear projection of the charity’s revenue from previous years to predict the amount by which we expect the revenue to increase or decrease in the next year. GFI has received funding influenced by ACE as a result of its prior Top Charity status, so in order to more accurately estimate their room for more funding, we have subtracted the estimated ACE-influenced funding from our estimates of future revenue, which means the charity’s real 2020 revenue could be higher than the revenue we predict.34 Comparing GFI’s estimated revenue for 201935 and 2020,36 this projection predicts a decrease in revenue between $3.1M to $5.5M.37 We believe this number does not accurately reflect GFI’s revenue projections. However, we include it to consistently apply the same revenue projection model to all organizations we evaluate in order to compare each of their room for more funding. GFI’s revenue appears lower than we believe is accurate partly because we have not included ACE-influenced revenue in order to account for our own impact.38 The estimates for change in revenue are more uncertain than the estimated costs of expansion, so we put limited weight on them in our analysis.39 This is especially true in the case of GFI, as the revenue projections deviate significantly from reasonable expectations.

In addition, GFI could use an additional $1.0M to $5.0M for research grants.40

Criterion 3: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

Overall Assessment:

Information about a charity’s track record can help us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments, which is information that cannot always be incorporated into our other criteria. An organization’s track record is sometimes a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences between two charities.

In this section, we consider whether each charity’s programs have been well executed in the past by evaluating some of the key results that they have accomplished. Often, these outcomes are reported to us by the charities and we are not able to corroborate their reports.41 We do not expect charities to fabricate accomplishments, but we do think it’s important to be transparent about which outcomes are reported to us and which we have corroborated or identified independently. The following outcomes were reported to us unless indicated otherwise.

Founded in October 2015 and officially launched in February 2016, GFI is a relatively young organization. Their Policy, Corporate Engagement, SciTech, and International Engagement programs were all established in 2016. In 2018, they launched their Competitive Research Grant Program. Below is our assessment of each of these programs prioritized by expenses in 2018–2019:

Programs

Program Duration

2016–present

Key Results

- Influenced two companies in Brazil to launch animal product alternatives (2018–2019)

- Influenced funding towards cell-cultured meat research in India42 (2018–2019)

- Launched GFI-Asia Pacific (2018), GFI-Europe (2019), and GFI-Israel (2019)

Our Assessment

GFI Brazil and India were launched in 2017. GFI’s Brazil team has expanded since then and has achieved some successes in accelerating the development of the plant-based food industry, including influencing a major egg company in Brazil to launch a plant-based egg in 2019.43 This seems to be the first product of its kind in Brazil44 and it will likely inspire other companies to launch similar plant-based products. Additionally, GFI assisted a start-up in launching a plant-based burger,45 which may have also contributed to accelerating the development of the industry in Brazil.

In India, GFI influenced the government to sponsor a center focused on cell-cultured meat research.46 They also secured additional funding for research in this field. We are highly uncertain about the effects of this program on animals because many of them are likely to occur in the long term. However, we do think these achievements may have contributed to the advancement of cell-cultured meat research in India.

GFI has continued to expand their affiliates to other countries, launching GFI-Asia Pacific in 2018,47 GFI-Europe in 2019, and GFI-Israel in 2019. Successes for these regions are yet to be seen.

Program Duration

2016–present

Key Results

- Influenced four “big meat” companies to launch plant-based alternatives in the U.S. (2018–2019)

- Achieved a commitment from Kellogg’s MorningStar Farms to transition their product line to 100% plant-based by 2021 (2018–2019)

- Published two Good Food Restaurant Scorecards ranking U.S. restaurants according to their plant-based options (2017–2018)

- Influenced a U.S. retailer to stock plant-based alternatives in the meat aisle (2018–2019)

- Conducted two expanded Nielsen market analyses on the U.S. retail sales of plant-based foods (2017–2018)

- Published Cell-based Meat and Plant-based Meat, Eggs, and Dairy State of the Industry Reports (2019)

Our Assessment

GFI reported engaging with 17 big food and meat corporations in 2017.48 In 2018–2019, they reported successfully influencing four out of eight big meat companies they approached to launch plant-based products, which will likely reduce the purchase of meat and promote plant-based alternatives in the U.S. market. In 2018, they achieved a corporate commitment from Kellogg’s MorningStar Farms that is set to reduce the purchase of millions of eggs per year.49 Although there are uncertainties about how many farmed animals will be spared by GFI’s corporate victories, it is very likely that they will reduce the number of farmed animal products purchased by these corporations, probably encouraging further commitments and increasing the total number of plant-based products in the U.S. food market.

Since 2017, GFI has published their annual ranking of restaurants. The 2018 ranking suggests that in one year, 10 top U.S. restaurants have improved their plant-based food offerings,50 although it is very difficult to determine whether GFI is responsible for this effect. Since 2018, GFI has engaged with U.S restaurant chains retailers by providing them with advice on assortment, marketing, and merchandising of plant-based food products, reporting some progress in this area.51 We believe that if GFI’s advice is generally accurate, this project would have increased accessibility and affordability of plant-based products, probably increasing plant-based products sales and reducing the demand for animal products.

Since 2017, GFI has developed an annual analysis of retail sales for plant-based foods in the U.S. based on Nielsen’s data,52 achieving media attention and hitting major outlets.53 Given that Nielsen’s data shows an increase in plant-based food sales, we believe it is likely that disseminating this information has somewhat encouraged investment, research, and development of plant-based products in the U.S. However, we are highly uncertain about the magnitude of this impact.

In 2019, GFI published a comprehensive report on the state of the U.S. plant-based food industry and another about the cell-cultured food industry, which seem like useful tools to promote further investment and development of these products.

Program Duration

2016–present

Key Results

- Advised the creation of international cell-cultured meat regulatory frameworks54 (2018–2019)

- Successfully opposed label censorship bills in 14 U.S. states (2018–2019)

- Successfully lobbied four times to include language supporting research into plant proteins in House and Senate reports accompanying Agriculture Appropriations bills55 (2018–2020)

- Successfully lobbied against a provision that would have given full oversight of cell-cultured meat to the USDA56

Our Assessment

Since 2017, GFI has been lobbying the House and the Senate, promoting plant-based and cell-cultured meat research and development. They reported successes in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020.57 They report that their most important policy achievement since 2018 has been the development of an international cell-cultured meat regulatory framework that was adapted for India, the U.K., and Singapore. Since most of this policy work is aimed to affect animals in the medium or long term, especially their efforts on cell-cultured meat regulatory frameworks, we are highly uncertain about the extent to which this work will affect animals.

GFI policy work has also focused on protecting U.S. plant-based food companies from labeling regulations that would put them at a disadvantage against animal agriculture industries. In 2017, they filed a petition with this purpose, and since 2018 they have opposed label censorship bills in 25 states, succeeding in 14.58 Although we are uncertain about the magnitude of the impacts, we believe GFI’s work to overcome regulatory obstacles for plant-based products has likely increased their commercialization in several U.S. states.

Program Duration

2018–present

Key Results

- Awarded almost $3 million of open-access plant-based and cell-cultured meat research funding to 14 recipients worldwide59 (2018)

Our Assessment

GFI launched this program in 2019, so its successes remain to be seen. However, we believe that providing funding for plant-based and cell-cultured meat research is likely to increase the supply of plant-based products and reduce the price of cell-cultured meat.

Program Duration

2016–present

Key Results

- Released at least 11 varied scientific publications on cell-cultured and plant-based meat (2017–2019)

- Conducted technical due diligence for at least six cell-cultured meat startup companies (2017–2019)

- Launched a course on plant-based and cell-cultured meat at Stanford University (2018)

- Developed a free plant-based and cell-cultured meat Massive Open Online Course60 (2018–2019)

- Helped UC Berkeley launch a Program for Meat Alternatives and Plant-Based Meat Innovation Lab, which has since expanded to include cell-cultured meat61 (2017–2019)

- Advised more than 225 food and life science companies about opportunities in the plant-based and cell-cultured meat industry62 (2017–2019)

Our Assessment

GFI’s work on science and technology has resulted in several publications (at least two in 2017, six in 2018, and three in the first six months of 2019), most of them related to cell-cultured animal products. These include a peer-reviewed article, two white papers, and an action paper that launched GFI’s Sustainable Seafood Initiative. This research has successfully informed GFI’s other projects, such as the advice they have given food and life sciences companies.63 It has also informed their courses, which have probably helped to promote more research and future development of plant-based and cell-cultured products.

Since 2017, GFI has conducted technical due diligence for at least six cell-cultured meat start-ups which reportedly have promoted investments of millions of dollars.64 Because the promotion of cell-cultured meat is focused on long-term impacts, we find it difficult to determine the extent to which this work has affected animals. However, we believe that GFI’s SciTech work is contributing to a transformation of the food industry with the potential to benefit a large number of farmed animals.

Criterion 4: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

Overall Assessment:

A charity’s recent cost-effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component to understanding how cost-effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources and compare that to the outcomes they have achieved in each of their main programs.

This year, we have used an approach in which we more qualitatively analyze a charity’s costs and outcomes. In particular, we have focused on the cost-effectiveness of the charity’s specific implementation of each of its programs in comparison to similar programs conducted by other charities we are reviewing this year. We have categorized the charity’s programs into different intervention types and compared the charity’s outcomes and expenditures from January 2018 to June 2019 to other charities we have reviewed in our 2019 evaluations. To facilitate comparisons, we have also compiled spreadsheets of all reviewed charities’ expenditures and outcomes by intervention type.65

Analyzing cost-effectiveness carries some risks by incentivizing behaviors that, on the whole, we do not think are valuable for the movement.66 Particular to the following analysis, we are somewhat concerned about our inclusion of staff time and volunteer time. Focusing on staff time as an indicator of cost-effectiveness can reward charities that underpay their staff, and discourage organizations from working towards increasing salaries to be more in line with the for-profit sector. As for volunteer time, we think that volunteer programs can increase the cost-effectiveness of a charity’s work, however, overreliance on volunteers can make a charity’s work less sustainable. While we think that these factors are relevant and worth including in our analysis of cost-effectiveness, we encourage readers to bear these concerns in mind while reading this criterion.

Overview of Expenditures

The following chart shows GFI’s total expenditures in 2018 and 2019, divided by program.67

We asked GFI to provide us with their expenditures for their top 3–5 programs as well as their total expenditures. The estimates provided in the graph were calculated by dividing up their total expenditures proportionately, according to the size of their programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost-effectiveness.

Capacity Building/Building Alliances

Summary of outcomes: conducted a study in Brazil; published a market report in Brazil; co-hosted The Future of Protein Summit in India; established government partnerships in Brazil, India, and the U.K.; provided support to industry in Brazil, India, and Asia-Pacific; published various research publications; created academic courses for plant-based and cell-based meat; conducted technical due diligence for cell-cultures meat start-up companies; provided consultancy to food and life science companies; and granted ~$3 million to plant-based and cell-cultured meat R&D. For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in capacity building/building alliances.

Note: GFI has three programs that we have categorized together under capacity building/building alliances—their SciTech program, their Competitive Research Grant Program, and their International Engagement program. The latter includes outcomes that overlap with many of the other intervention types in this section of the review. We have categorized GFI’s International Engagement program as capacity building, primarily because cell-cultured and plant-based meat advocacy is not well-established in many of the regions they have expanded to, and initial work there has an overall effect of building the capacity of those regions. That said, we acknowledge that this program does not fit as well into capacity building as the other two of their programs and some programs from other reviewed charities.

Use of resources

Table 1: Estimated resource usage in GFI’s capacity building/building alliances Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Resources | GFI’s SciTech | GFI’s International Engagement | GFI’s Competitive Research Grant Program | Average across all reviewed charities68 |

| Expenditures69 (USD) | $1,500,000 | $2,200,000 | $2,900,000 | $1,400,000 |

| Staff time (weeks70) | 504 | 200 | Incl. in SciTech | 316 |

| Volunteer time (weeks71) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 55 |

Relative to their expenditures for this program, GFI’s staff time is much lower than the average of charities we reviewed this year. Note that GFI’s work differs substantially from the other charities we reviewed, so comparisons to the average should be given relatively less weight than for other charities.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

Capacity building encompasses a broad category of outcomes for animals that are typically indirect, and as such it is difficult to make an assessment of their cost-effectiveness. As they were the only one of two reviewed charities that reported conducting research, we are particularly uncertain as to how cost effective it’s implementation has been. GFI’s SciTech program focuses on creating and publicizing research that they then use to inform their consultancy work with start-ups and other food and life sciences companies. Their publications have included one peer-reviewed journal article, two white papers, and at least five other assorted research publications. Through their grant program they have provided ~$2,900,000 in funding for 14 R&D projects relating to the production of plant-based and cell-based meat. As their work is focused on providing research that can be used by all companies and researchers, it seems that this would be substantially more cost effective than equivalent funding towards individual companies. That said, their research programs have an impact for animals only to the extent to which they affect the behavior of plant-based or cell-based meat stakeholders in a way that improves the chances of the products becoming successful. We think it’s likely that they do have an effect, but this does add to our uncertainty of their cost-effectiveness.

GFI’s International Outreach program has established GFI affiliates in Brazil, Europe, Israel, India, and Asia-Pacific, and conducts mostly capacity building activities in those locations. As one of a very small number of groups doing similar work in the plant-based and cell-cultured space, it seems likely that the neglectedness of their work will mean it is particularly cost effective, all else equal.

As GFI’s impact centers around improving the availability of plant-based and cell-cultured animal products, the aspects of their capacity building that are likely to be most cost effective are those that have the most substantial impact on this central outcome. Of their capacity-building work, we expect that work such as publicizing and funding open source research, providing consultancy with start-ups, and building relationships with governments will be most impactful, as they increase the chances for all companies working in the space to develop new products and have them approved for market.

Compared with other charities’ capacity-building programs, GFI appears to have achieved above average outcomes when accounting for their expenditures, indicating that their capacity building may be particularly cost effective when compared to other, similar interventions.

Legal Advocacy

Summary of outcomes: advised the creation of international cell-cultured meat regulatory frameworks; made progress towards shaping the U.S. cell-cultured meat regulatory framework; made progress lobbying for federal plant-based and cell-cultured meat R&D in the U.S.; made progress opposing label censorship legislation in U.S.; and made progress advocating for plant-based milk labels in U.S. For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in legal advocacy.

Use of resources

Table 2: Estimated resource usage in GFI’s legal advocacy, Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Resources | GFI | Average across all reviewed charities72 |

| Expenditures73 (USD) | $3,600,000 | $500,000 |

| Staff time (weeks74) | 464 | 187 |

| Volunteer time (weeks75) | Unknown | 12 |

Relative to their expenditures for this program, GFI’s staff time is much lower than the average of charities we reviewed this year. Note that GFI’s work differs substantially from the other charities we reviewed, so comparisons to the average should be given relatively less weight than for other charities.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

GFI conducts legal advocacy in a variety of applications, and as such the cost-effectiveness of this program likely has a large degree of variation. As a lot of GFI’s legal advocacy work is in progress and has outcomes for animals that are indirect, we are particularly uncertain in our assessment of their cost-effectiveness. Additionally, some of their legal work has required several years of work, so only considering their expenditures over an 18-month period may lead us to overestimate the cost-effectiveness of those outcomes.

As GFI’s impact centers around improving the availability of plant-based and cell-cultured animal products, the aspects of their legal work that are likely to be most cost effective are those that have the most substantial impact on this central outcome. In legal advocacy, we think this is likely to be work that is focused on system-wide change as, although harder to secure, it has the opportunity to affect a larger number of animals and secures legal progress that can be built from in future campaigns. Most of their work seems to be of this nature—e.g. the creation of regulatory frameworks to allow cell-cultured meat production in the U.K., India, and Singapore, their work on regulatory frameworks, R&D lobbying in the U.S., and their work on labeling.

After accounting for all of their outcomes and expenditures, GFI’s Legal Advocacy program seems close to the average cost effectiveness of other reviewed charities in 2019.

Corporate Outreach

Summary of outcomes: secured a commitment from Morningstar Farms to go 100% plant-based; approached eight “big meat” companies, four of which are launching plant-based product lines; published the “Good Food Restaurant Scorecard”; ran a webinar for chefs; influenced a retailer to stock plant-based alternatives in the meat aisle; and organized plant-based market research conducted by Nielsen. For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in corporate outreach.

Use of resources

Table 3: Estimated resource usage in GFI’s corporate outreach, Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Resources | GFI | Average across all reviewed charities76 |

| Expenditures77 (USD) | $1,200,000 | $1,200,000 |

| Staff time (weeks78) | 380 | 380 |

| Volunteer time (weeks79) | Unknown | 0 |

Relative to their expenditures for this program, GFI’s staff time is close to the average of charities we reviewed this year. Note that GFI’s work differs substantially from most of the other charities we reviewed, so comparisons to the average should be given relatively less weight than for other charities.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

GFI has achieved some direct outcomes for animals, such as the commitment from Morningstar Farms to go 100% plant-based, reportedly reducing the need for 300 million eggs (or ~1 million chickens) when implemented. Similarly, four “big meat” companies have launched or are reportedly planning to launch plant-based product lines which will likely directly impact animals by reducing the demand for meat products. Over time, this may also nudge meat companies towards incorporating more plant-based alternatives if the lines are successful. The extent to which extent GFI is responsible for those outcomes is unclear.

Their other outcomes all serve to increase the acceptance and prevalence of plant-based products in different ways which, to the extent that they are successful, will have a clear impact in reducing the demand for animal products as a whole. However, as their impact for animals is primarily indirect, and there aren’t other charities doing similar work to their corporate outreach program, we are more uncertain of their cost-effectiveness than for charities with more typical corporate outreach programs addressing welfare issues.

After accounting for all their outcomes and expenditures, GFI’s corporate outreach seems close to the average cost effectiveness of other reviewed charities in 2019.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

Overall Assessment:

By conducting reliable self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs and modify or discontinue less successful programs. When such systems of improvement work well, all stakeholders benefit: Leadership is able to refine their strategy, staff better understand the purpose of their work, and donors can be more confident in the impact of their donations.

In this section, we consider how the charity has assessed its programs in the past. We then examine the extent to which the charity has updated their programs in light of past assessments.

How does the charity identify areas of success and failure?

Last year, GFI implemented an Objectives, Key Results and Actions process (OKRA) in order to set measurable goals and track their progress towards those targets.80 Within this framework, each department sets its own expected key results, which are reassessed quarterly with leadership. Each team provides a ranking for their progress on each of the key results, then they discuss what was not accomplished and what needs to be reprioritized.81

In the past three years, GFI has consulted (pro bono) with external individuals and organizations to get advice on different topics, including consumer insights, editorial content, marketing tools and technologies, regulations and policies, the science behind plant-based and cell-cultured meat, and organizational culture and structure.82

Does the charity respond appropriately to identified areas of success and failure?

We believe that GFI responded appropriately to their self-determined areas of success and failure in at least two ways, listed below.

- GFI recognizes that as a remote organization, they face common organizational culture challenges, especially work-life balance related issues.83 They have made efforts to improve their remote culture by hiring a Culture & Engagement Specialist whose full-time job consists of maximizing the cohesion and strong culture across GFI’s remote workplace and conducting biannual anonymous staff surveys.84 GFI reports that in order to address work-life balance issues, which they have identified as one of their major weaknesses since last year,85 they have hired assistants in each department to provide administrative support and coordination, probably helping to ease staff’s workload.86

- GFI has been working to influence funding towards plant-based and cell-cultured meat research by (i) seeking funding opportunities from private foundations and governmental grant-making agencies for academic research institutes and start-ups, (ii) presenting investors and venture capital groups with opportunities in the industry, and (iii) engaging the USDA to direct more funding towards plant-based research. Thanks to this work, GFI reportedly influenced funding to many plant-based and cell-cultured meat companies and aided in persuading the USDA to facilitate plant-based research funding. Based on these intermediary achievements, GFI decided to strengthen their role in directing funding towards plant-based and cell-cultured meat research by launching a Competitive Research Grant Program. According to data provided by an article in Nature magazine, GFI’s first round of grants has already doubled the total funding for cell-cultured meat open-access science in the past two decades. Although it may be risky to start a new research grant program at such a large scale, it seems to be a promising intervention for GFI to start influencing funding for open-access research directly. In addition, the grants were given to scientists in different countries, promoting scientific research on plant-based and cell-cultured meat at an international level.87

We believe that GFI failed to respond appropriately to areas of success and failure in at least the following way:

We believe that GFI could take additional steps to respond to their lack of viewpoint diversity within their board. In our previous review, we noted concerns about this issue, especially regarding the fact that several of the board members had significant ties to the Executive Director who also served on the board himself.88 Although GFI reports that their leadership embraces a challenge culture and has an anonymous employee reporting system monitored by the Secretary of the Board,89 GFI’s board members have not changed, and we are still concerned that the Executive Director’s views could frequently go unchallenged.

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

Overall Assessment:

Strongly-led charities are likely to be more successful at responding to internal and external challenges and at reaching their goals. In this section, we describe each charity’s key leadership and assess some of their strengths and weaknesses.

Part of a leader’s job is to develop and guide the strategic vision of the organization. Given our commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we look for charities whose strategy is aligned with that goal. We also believe that a well-developed strategic vision should be feasible to achieve. Since a well-developed strategic vision is likely the result of well-run strategic planning, we consider each charity’s planning process in this section.

Key Leadership

Leadership staff

Bruce Friedrich is GFI’s Co-Founder and Executive Director. He has a long history of animal advocacy and an interest in effective altruism, and he is largely responsible for setting the strategy and tone of the organization. Other key leaders at GFI include Jessica Almy (Director of Policy), Annie Cull (Director of Communications), Alison Rabschnuk (Director of Corporate Engagement), David Welch (Director of Science and Technology), Sarah David (General Counsel and Director of Finance), Susan Halteman (Director of Development), and Reannon Branchesi (Director of Operations and Administration).

According to a culture survey90, 91 that we distributed to GFI’s team, respondents generally agree that leadership is attentive to the organization’s strategy and promotes both internal and external transparency.

Board of Directors

GFI’s Board of Directors consists of five members, including Executive Director Bruce Friedrich. In the U.S., it’s considered a best practice for nonprofit boards to be comprised of at least five people who have little overlap with an organization’s staff or other related parties. However, there is only weak evidence that following this best practice is correlated with success.

While GFI’s board members have relevant occupational backgrounds—including accounting, finance, management, and legislation—two board members have been strongly affiliated with Mercy For Animals (MFA),92 which helped found GFI, and several of the board members have significant ties to Friedrich.93 As we mentioned in our previous reviews, we have been concerned about the potential lack of viewpoint diversity of GFI’s board, especially about Friederich’s views being unchallenged.

We consider the board’s relative lack of diversity in occupations and experiences to be a weakness. We believe that boards whose members represent occupational and viewpoint diversity are likely most useful to a charity since they can offer a wide range of perspectives and skills. There is some evidence suggesting that nonprofit board diversity is positively associated with better fundraising and social performance,94 better internal and external governance practices,95 as well as with the use of inclusive governance practices that allow the board to incorporate community perspectives into their strategic decision making.96

Strategic Vision and Planning

Strategic vision

GFI’s mission is to create “a sustainable, healthy, and just food system” using the power of food innovation and markets to accelerate plant-based and cell-cultured meat.97 Although GFI’s mission does not emphasize reducing suffering, it implies a transformation in the food system that will bring large benefits for farmed animal suffering by shifting markets towards plant-based and cell-cultured meat. GFI’s mission also implies achieving benefits for other causes related to the food system, such as global poverty, human health, and environmental degradation, which can support the growth of the farmed animal advocacy movement as a whole.

Strategic planning process

After revising the strategic plan every six months, GFI decided last year to conduct an analysis and update of their strategic plan98 on an annual basis. They report that each department director, working together with their team, is responsible for the strategic planning for their area. Although every employee in the organization is encouraged to have a say in all aspects of the entire strategic plan, most people only weigh in on their own area.99 GFI reports that this process is based on a decision-making model they have been implementing in collaboration with a pro-bono consultant from Bain & Company. In addition, the Executive Director has weekly or biweekly meetings with every director during which they discuss the strategy for their “zones.”100

Goal setting and monitoring

The implementation of the Objectives, Key Results and Actions (OKRA) framework has facilitated GFI’s process of goal setting and monitoring. Each quarter, they revise each department’s expected Key Results and Actions, which are set in alignment with GFI’s general organizational Objectives.101 Although they have recently implemented this OKRA framework, we believe it has helped GFI to set measurable goals within a specific time frame and with an explicit outcome, and we expect it to help GFI to identify their most impactful programs once the new system is fully implemented.

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Overall Assessment:

The most effective charities have healthy cultures and sustainable structures to enable their core work. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about the culture they try to foster and their perceptions of staff morale. We review each charity’s policies related to human resources and check for essential items. We also send each charity a culture survey and request that they distribute it among their team on our behalf.

Human Resources Policies

Here we present a list of policies that we find to be beneficial for fostering healthy cultures. A green mark indicates that GFI has such a policy and a red mark indicates that they do not. A yellow mark indicates that the organization has a partial policy, an informal or unwritten policy, or a policy that is not fully or consistently implemented. We do not expect a given charity to have all of the following policies, but we believe that, generally, having more of them is better than having fewer.

| A workplace code of ethics that is clearly written and consistently applied throughout the organization | |

| Paid time off In the U.S., GFI offers 12–18 days depending on tenure. |

|

| Sick days and personal leave In the U.S., GFI offers 10 sick days, a personal day every six months, and six days of bereavement leave each year. |

|

| Full healthcare coverage In the U.S., GFI offers up to full coverage of their employees’ healthcare premiums, as well as a 50% cost share of employees’ vision and dental premiums and flexible or dependent care spending accounts. |

|

| Regular performance evaluations | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| A formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries |

| A written statement that they do not discriminate on the basis of race, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A written statement supporting gender equity and/or discouraging sexual harassment | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| An optional anonymous reporting system | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment or discrimination through all levels of the managerial chain up to and including the Board of Directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| A practice in place of documenting all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular, mandatory trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) | |

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for submitting reasonable accommodation requests | |

| Remote work option |

| Audited financial documents (including the most recently filed IRS form 990, for U.S. organizations) made available on the charity’s website | |

| Board meeting notes made publicly available | |

| Board members’ identities made publicly available | |

| Key staff members’ identities made publicly available |

| Formal orientation provided to all new employees | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Funding provided for books or other educational materials related to each employee’s work | |

| Paid trainings available on topics such as: diversity, equal employment opportunity, leadership, and conflict resolution | |

| Paid trainings in intercultural competence (for multinational organizations only) | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support |

Culture and Morale

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly towards all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. According to GFI’s leadership, their culture is excellent, and staff regularly describe the workplace as “caring” and “compassionate” in their biannual staff surveys. Two areas for improvement that they noted are their work-life balance and the difficulties with culture that can arise from being a remote team. To help address work-life balance, GFI has hired assistants to provide administrative support and ease the workload of their specialists in each department. To aid their remote culture, they hold two all-staff retreats each year and have an “in-depth” onboarding process for staff, in which they meet individually with every other staff member over the course of several months and are paired with a buddy to support them in their initial three months. They also have social activities such as “a book club, a cooking club, coffee chats, and happy hours.” In the staff survey we distributed, we did not find evidence that there are issues with their remote culture. Regarding work-life balance, while staff were generally very positive about the benefits that GFI provides, a small number of staff noted that they were unsatisfied with the amount of vacation time offered.

According to the survey we distributed, GFI has a high level of employee engagement. Additionally, 32 employees described GFI’s internal communication style as “transparent,” “open,” “honest,” or similar, 24 described it as “friendly,” “compassionate,” “warm,” or similar, and 17 described it as “thorough,” “detailed,” “thoughtful,” or similar.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion102

One important part of acting responsibly towards stakeholders is providing a diverse,103 equitable, and inclusive work environment. Charities with a healthy attitude towards diversity, equity, and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, which improves their ability to respond to new situations and challenges.104 Among other things, inclusive work environments should also provide necessary resources for employees with disabilities, require regular trainings on topics such as diversity, and protect all employees from harassment and discrimination.

GFI’s leadership report that they are committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion. They report having gender diversity, and more recently they are seeing results in improving racial diversity. They cite their recent hiring outcomes as evidence of this—in the last year, 25% of their new hires have been people of color. They report that this is a result of intentional practices to improve racial diversity, such as broader job advertising, inclusive messaging in job description, and rubrics to mitigate unconscious bias.105

According to our culture survey, most staff agreed that GFI has staff from diverse backgrounds. Many noted that while GFI is still not as diverse as it should be, it is seriously prioritizing this issue. When staff were asked how GFI could further improve, hiring practices emerged as a general theme, although there weren’t any specific suggestions that were prevalent. Most staff felt that GFI provides sufficient training on issues of discrimination, inclusivity, sexual misconduct, and diversity, and that they are protected from harassment and discrimination in the workplace.

Sustainability

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in leadership. The charity should not seem likely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, it should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

GFI receives most of its funding from small to medium sources and has not received a grant larger than 20% of its budget since 2017. They expect to receive larger grants in the future, and their current plans for 2020 are dependent on securing additional funding of that nature. They aim to keep an operating reserve of 10–12 months, but they do not seem likely to be able to maintain that level with their planned $8.7 million expenditure in 2019.

In our view, Friedrich takes a very large share of the responsibility for the organization’s success, and he may be difficult to replace if the occasion should arise. However, GFI is a fairly large organization with a talented and committed staff. They have well-documented policies and training materials. Their strategic plan would provide guidance through any leadership transitions, at least for the first year, as it is currently renewed annually. We think that GFI would likely survive a potential change in leadership.

Questions for Further Consideration

GFI has expanded to several countries with cultural and social circumstances very different from the U.S. How is GFI addressing challenges arising from their international expansion?

GFI’s Response:

“GFI has been very deliberate in building healthy, dynamic global affiliates at a gradual pace. We currently have established affiliates in Brazil, India, Asia Pacific, Europe and Israel, with each affiliate playing a unique role in creating a sustainable and humane global food system:

GFI-Brazil—GFI-Brazil launched in January 2017 with the hire of Managing Director Gus Guadagnini and has since grown to a team of six. We established GFI-Brazil as our first international affiliate because Brazil has the largest meat company in the world and has world class agricultural science and government funding for agricultural R&D. Until a few years ago, industry, government, and the public were generally unaware of alternative proteins in Brazil. In just two years, GFI-Brazil has established a wide network of companies, entrepreneurs, government officials, and industries eager to invest in the development of new alternative protein products and businesses. This industry network is also a crucial component of our policy work as many of these multinational corporations have close relationships with the government.

GFI-India—GFI-India launched in December 2017 with the hire of Managing Director Varun Deshpande and has since grown to a team of seven. India, which is likely to be the world’s most populous country within the next decade, is a prime market for alternative protein solutions to malnutrition, and these solutions are potential fuel for robust domestic economic growth. Our long-term goal for GFI-India is twofold: forestalling domestic growth in per capita consumption of animal-sourced foods while contributing to the growth of the alternative protein sector globally. GFI-India aims to establish India as a sourcing base for plant-based protein and to cultivate a scientific talent pool for cultivated meat research and manufacturing.

GFI-Asia Pacific (GFI-APAC)—GFI-APAC launched in July 2018 with the hire of Managing Director Elaine Siu and has since grown to a team of four. GFI-APAC is currently focused on alternative protein advancement in China, Hong Kong, and Singapore, all areas in which we can create extremely high impact:

- China, as the most populous country in the world, is projected to be responsible for 27% of global meat consumption by 2026. The country spends billions of dollars annually on agricultural research, wants to be a leader on climate change, and has many world-class scientific institutions.

- Hong Kong is one of the major financial centers in APAC and is still the first-choice launch pad for global investors and corporations seeking to become active in this region.

- Singapore has the most friendly and committed government to date in developing the alternative protein industry, including funding for public research, aggressive policy development, and a vibrant startup and R&D scene. By focusing on Singapore, we are also able to influence Southeast Asian markets including Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand, because products routinely flow from Singapore into these markets.

In its short tenure, GFI-APAC has influenced alternative protein development in the region and has ambitious goals to advance alternative protein science, policy, corporate engagement, and innovation in the coming years.

GFI-Europe—GFI-Europe launched in February 2019 with the hire of Managing Director Richard Parr and should be a team of four by the end of 2020. Europe presents enormous opportunities to advance GFI’s mission: it has a population more than twice that of the U.S., a GDP approximately equal to it, is home to much of the world’s scientific and commercial talent, and is one of the biggest potential markets for alternative proteins. Moreover, Europe influences the world through trade, migration, diaspora communities, and thought leadership.

GFI-Israel—GFI-Israel has formally launched with the September 2019 hire of Managing Director Nir Goldstein, who joins Senior Scientist Tom Ben-Arye, who has been representing GFI in Israel since March. Israel, often referred to as the “Startup Nation,” is renowned for its innovative technology, entrepreneurial spirit, supportive government policies, investment capital, and support for basic research. Israel is also recognized as a world leader in agriculture research, crop innovation, stem-cell research, tissue engineering, microbiology, and nanotechnology. Israel has become a hub for cultivated meat company development and is playing a significant role in the innovation of alternative proteins globally.

Our greatest challenge to date has been creating legal agreements, financial structures, and reporting requirements that allow GFI to provide financial support to these key regions, while also creating a legally compliant organizational structure for GFI. We are challenged by the disparate, complex legal and political climates in each region, which require very careful navigation to ensure we’re adhering to all relevant laws and regulations. We have increased U.S. staff capacity to address this challenge: our new general counsel and finance manager help manage our financial and legal relationships with our affiliates and our Associate Director of International Engagement operates within GFI’s Executive team to ensure all interactions with our international teams have the full support of GFI leadership.

Our other greatest challenge to date has been navigating very different fundraising cultures with vastly different philanthropic resources across each of the five regions. We are addressing this challenge by hiring highly experienced development staff for each international affiliate and by ensuring our U.S. team provides our affiliates with a financial safety net and the resources they need to thrive.

We are continually incorporating lessons learned from GFI’s first four years in operation to provide guidance to all of our international affiliates around fundraising, hiring, communications, and managing team growth.”

There are many more farmed fishes than other species of farmed animals. Has GFI considered allocating more of their resources towards reducing the suffering of farmed fishes?

GFI’s Response:

“GFI has identified plant-based and cultivated seafood as two important, neglected, and tractable approaches for replacing conventional seafood. Since our founding in 2016, we have allocated significant resources to accelerating the development and commercialization of scalable plant-based and cultivated seafood products that compete on taste, price, and nutritional quality with their ocean-derived counterparts.

In 2017, we co-designed and launched a semester-long program to develop plant-based seafood within the UC Berkeley Plant-based Meat Challenge Lab at the Sutardja Center for Entrepreneurship and Technology.