Cellular Agriculture Society

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2018 |

Archived Version: November, 2018

Overview

What does the Cellular Agriculture Society do?

The Cellular Agriculture Society (CAS) is an international nonprofit dedicated to the advancement of cellular agriculture and the commercialization of cellular agriculture products. They are also working to promote cellular agriculture globally and to create an international movement. Programming at CAS falls into three categories: “Initiatives” are based on narrow topics, “divisions” include broader topics led by the Directors on the executive board, and “series” are reoccurring application-based programs.

What are their strengths?

CAS has a well-designed online presence—they provide an attractive platform from which to build an international movement. They are committed to a high level of excellence and to producing high-quality work by using a research-driven approach. As a young organization with limited resources, they are particularly focused on working as cost-effectively as possible.

What are their weaknesses?

CAS was launched in early 2018, so their track record is quite short and does not yet include some of the outcomes they most hope to accomplish (e.g., the successful development of cultured alternatives to animal products). We expect that it will take some time—perhaps decades—to develop cultured meat that can compete commercially with conventional meat. They are still working to determine their area of primary focus, having already taken on a number of different projects.

Table of Contents

- How The Cellular Agriculture Society Performs on our Criteria

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Supplementary Materials

How the Cellular Agriculture Society Performs on our Criteria

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Before investigating the particular implementation of a charity’s programs, we consider their overall approach to animal advocacy in terms of the cause(s) they advance and the types of outcomes they achieve. In particular, we consider whether they’ve chosen to pursue approaches that seem likely to produce significant positive change for animals—both in the near and long term.

Cause Area

CAS focuses primarily on developing cultured alternatives to animal products, which will benefit farmed animals. We believe farmed animal advocacy to be a high-impact cause area.

Types of Outcomes Achieved

To better understand the potential impact of a charity’s programs, we’ve developed a menu of outcomes that describes five avenues for change: influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

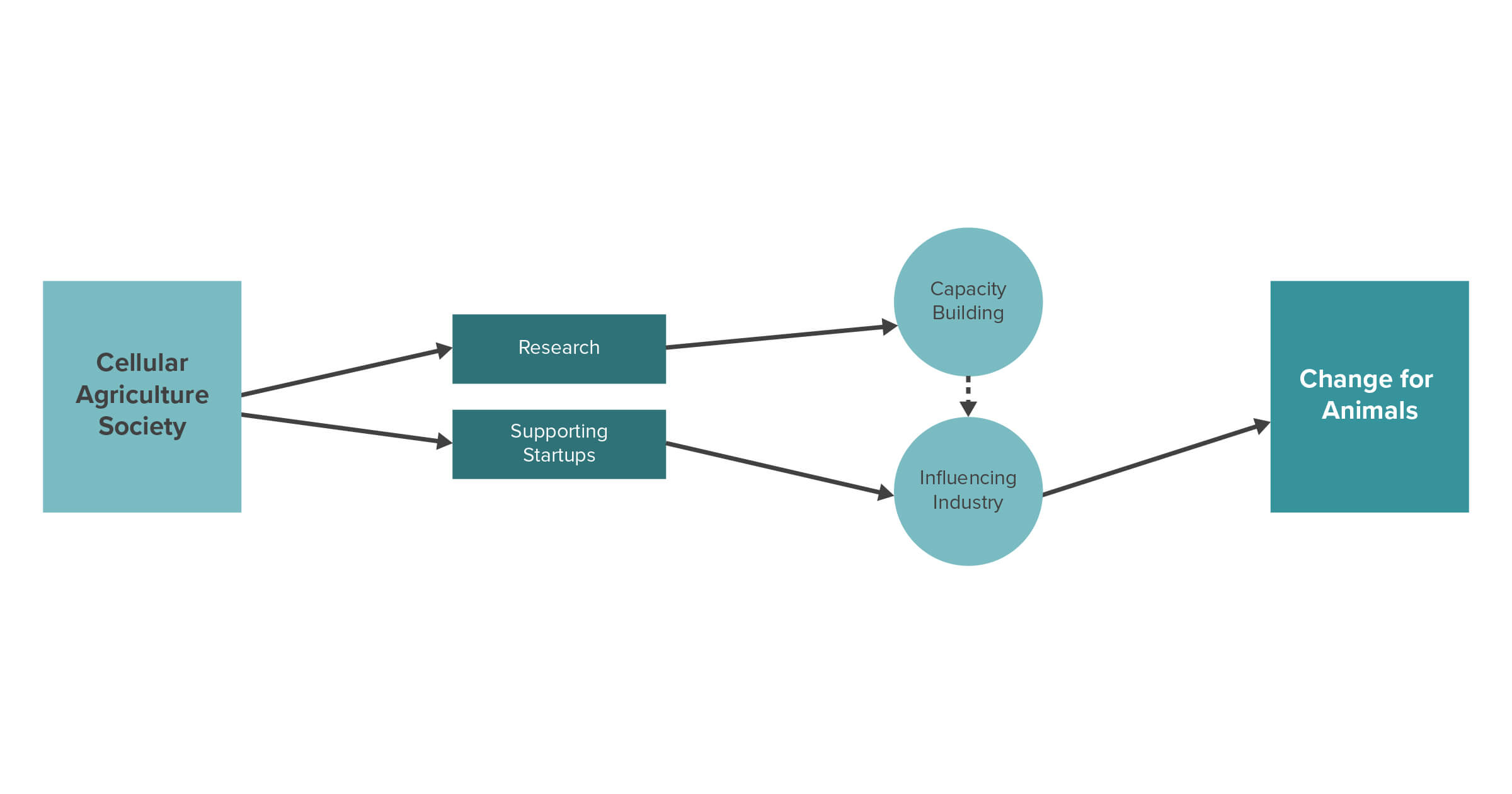

CAS pursues a couple of different avenues for creating change for animals: they work to build the capacity of the movement and influence industry. Pursuing multiple avenues for change allows a charity to better learn about which areas are more effective so that they will be in a better position to allocate more resources where they may be most impactful. However, we don’t think that charities that pursue multiple avenues for change are necessarily more impactful than charities that focus on one.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small and/or uncertain effects.

Capacity Building

CAS’s work to bring cellular agriculture into academic settings is a form of capacity building. Working to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement can have far-reaching impact. While capacity-building projects may not always help animals directly, they can help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Our recent research on the way that resources are allocated between different animal advocacy interventions suggests that capacity building is currently relatively neglected compared to other outcomes, such as influencing public opinion and industry.

CAS has been working with The Good Food Institute (GFI) to create the first university course in cultured meat, which will start at Stanford University in the coming year. They are hoping to launch a similar course at Harvard in the future.1 While we think the development of such courses and research centers is promising—since they plausibly provide additional entry points for people to get involved and work in the field—we’re generally unsure about the marginal impact of efforts to recruit students and scientists to work in food technology.

In addition to this course development, they are also working to develop an informational website, and the first cellular agriculture textbook2—as of October 2018, they report being close to finalizing a publishing contract.3 It’s our view that a textbook would probably be a valuable addition to existing resources and might contribute to the development of more university courses. They also have a chapter division supporting university CAS chapters to lead events and campaigns to spread knowledge of and involvement in cellular agriculture. While there is too little evidence to make an assessment of marginal impact for these relatively unique approaches to supporting the field of cellular agriculture as a science, all of these efforts may help to increase the amount of people working in this field, and having more scientists and engineers working on these issues from different perspectives may speed progress.

Influencing Industry

We think that creating and marketing cultured products is a potentially high-impact way to influence the food system.4 Successfully increasing the quality and availability of cultured and plant-based foods may help to create a climate in which it’s easier for individuals to reduce their use of animal products. Plant-based milk, for example, is already showing a tendency to displace the sales of conventional milk in the U.S.5 In the long term, this reduced demand for animal-based products could weaken the animal agriculture industry—potentially lessening its lobbying power and enabling stricter regulation of animal welfare standards.

CAS works to support cultured meat startups by connecting them with funding and potential employees, assisting with naming and design needs, and providing general counsel.6 They are also working to develop resources, such as effective naming conventions and high-quality stock images depicting cultured meat facilities to be used across the industry for press releases and presentations.7 To the extent that this work contributes to the success of cultured animal products, the impact for animals could be significant. CAS is doing some work in this area that we’re not aware of other charities doing—such as working on marketing issues (including naming and design needs and the creation of stock images). We think the marginal impact of work that others aren’t doing is likely to be higher than that of work that is being done by multiple entities, but it is unclear what the impact of this work will be or whether other organizations might be better positioned to do that work (in this case that might be marketing firms, for example). We think CAS’s work to connect cellular agriculture startups with funding and potential employees is promising and also relatively neglected.

Long-Term Impact

Though there is significant uncertainty regarding the impact of interventions in the long term, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.8 The potential number of individuals affected by a charity increases over time due to both human and animal population growth, as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Predictions about the long-term impact of any intervention are always extremely uncertain, because the effects of an intervention vary with context and are interdependent with concurrent interventions—with neither of these interactions being constant over time.9 When estimating the long-term impact of a charity’s actions, we consider the context in which they occur and how they fit into the overall movement. Barring any strong evidence to the contrary, we think the long-term impact of most animal advocacy interventions will be net positive. Still, the comparative effects of one intervention versus another are not well understood.10 Because of the difficulties in forecasting long-term impact, we do not put significant weight on our predictions.

Most of CAS’s strategy is directed towards long-term goals. Because so much of their work focuses on large-scale change and there are many obstacles to overcome, the potential for impact is mostly in the long term. The long-term impact of CAS’s work on the development of cellular agriculture is potentially very positive and, at the same time, highly uncertain. The impact could be hugely transformative if the industry is successful in developing cultured products that would plausibly alter the consumer landscape from one where we need to ask for a significant behavior change—from eating meat to not eating meat—to one where we only need to ask for a relatively small behavior change—from eating one kind of meat to eating another. However, the ultimate success of this outcome relies on (i) consumer acceptance of cultured products and (ii) the ability of the cellular agriculture industry to reach cost-competitiveness with the animal agriculture industry. Some evidence suggests that consumer acceptance of cultured meat may have improved in recent years but still remains low,11 but it remains unclear how long it will take for cultured meat to become cost-competitive, or if it ever will.12

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

In order to recommend a charity, we need to assess the extent to which they will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. Specifically, we need to consider whether there may be non-monetary “bottlenecks,” or barriers to the charity’s growth. First, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. Next, we evaluate the charity’s room for more funding by considering existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential new programs and areas for growth. It is important to determine whether any barriers limiting progress in these areas are solely monetary, or whether there are other inhibiting factors—such as time or talent shortages. Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for more funding sooner than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we have suggested. Our estimates are intended to indicate the point at which we would want to check in with a charity to ensure that they have used the funds they have received effectively and are still able to absorb additional funding.

Recent Financial History

CAS launched within the past year, with under $15,000 dollars in start-up funds. They recently received a grant for $50,000 from the Centre for Effective Altruism’s Animal Welfare Fund,13 and they are hoping to secure $500,000 by the end of the year.14 While they have laid the groundwork for a number of programs and they have 10 staff listed on their website, at the time of this writing, they do not yet have any paid full-time staff.15

Planned Future Expenses

Some of CAS’s largest future expenses will likely come from their goals to have several new paid staff positions filled, including a CEO, Communications Director, a C-Cubed Director, and a top program area Director.16 Aside from staffing, CAS has a number of projects on the horizon. These include funding research through fellowships,17 launching a volunteer platform, C-Cubed,18 and launching an additional website.19 While they have 17 programs listed on their website, they have decided to focus on a smaller selection—media, design, social science, and legal—as they start to get things off the ground.20

Assessing Funding Priority of Future Expenses

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area will likely vary in its potential cost effectiveness. In addition to evaluating a charity’s planned future expenses, we consider the potential impact and relative cost effectiveness of filling different funding gaps. This helps us evaluate whether the marginal cost effectiveness of donating to a charity would differ from the charity’s average cost effectiveness from the past year. We break down the total room for more funding into different priority levels, as follows:

High Priority Funding Gaps

Our highest priority is funding activities or programs that create longer-term impact in a cost-effective way, as well as programs which we have relatively strong reasons to believe will have a highly positive short- or medium-term direct impact in a cost-effective way.21

While CAS has expressed concerns about growing too quickly,22 we see having some key staff positions funded and filled as having a high potential to increase their impact, and we estimate that this is where they have the largest funding gap. Considering this, along with their work to support research and support startups, we estimate that CAS has a high priority funding gap of $630,000–$1.4 million in 2019.23, 24, 25

Low Priority Funding Gaps

It is of low priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively lower marginal cost effectiveness, or to replenish cash reserves. Because it is likely that there may be future expenditures we haven’t thought of, we also include in this category an estimate of possible additional expenditures (based on a percentage of the charity’s current yearly budget).

While CAS reported planning to focus on a few high priority projects,26 we still have some concerns about them potentially trying to take on too many different causes in their initial formative period. We think their work on an additional website detailing the problems with animal agriculture is of relatively low priority, since the websites of many other animal charities are already fulfilling this function. We estimated that CAS has a low priority funding gap of $140,000–$420,000 for 201927 by considering (i) the development of this additional website, (ii) possible lower priority research that may affect fewer animals,28 and (iii) a range of 1%–20% of their projected 2018 expenses.

The chart below shows the distribution of CAS’s gaps in funding among the three priorities: 29

Given their short history and lack of paid staff, it is highly uncertain how quickly CAS will be able to grow. They are currently planning to develop slowly and carefully rather than grow too fast, at least in this start-up phase.30 While they suggest there is no clear maximum for funding—since large amounts could be directed to supporting many Researchers and startups—they estimate that they could use, as a minimum, something in the low-to-mid six-figure range.31 There is a great deal of uncertainty in predicting their future trajectory given this early stage. We estimate that next year they have a total funding gap of approximately $540,000 to $1.7 million,32 and that they could effectively put to use a total revenue of $1.3 million–$2.2 million.33 While this is much higher than their current anticipated revenue of approximately $500,000 for 2018, we think they will benefit significantly from having paid staff and additional resources for their research programs and support of startups.

Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

We think quantitative cost-effectiveness estimates are often useful factors in charity evaluations, but we are concerned that assigning specific figures can be misleading and can make these estimates appear to carry more weight in our evaluation than we intend. For CAS in particular, we believe that our best estimate of their cost effectiveness is too speculative to feature in our review or include as a significant factor in our evaluation of their effectiveness. For instance, in thinking about CAS’s impact we considered the probability of their upcoming university course leading to an acceleration of the timeline in which cost-competitive cultured meat reaches the market (to the extent that this is due to the work of the scientists the course influences). Our estimates for these factors were very speculative; we considered other unknowns as well, and we omitted many possible scenarios for simplicity.

Additionally, CAS is focused on helping animals in the medium and long term, and we have not published estimates of the medium-term or long-term impacts of any other charities—so we worry that including this in a cost-effectiveness calculation would be unfair to those other organizations.34 Our lack of a cost-effectiveness estimate for CAS does not necessarily indicate that they have lower overall cost effectiveness than the charities for which we have completed a cost-effectiveness estimate.

In the future, we hope to have better ways of evaluating medium- and long-term impacts, which could lead to publishing a cost-effectiveness estimate for CAS. We think cost-effectiveness calculations will still be most useful as one small component in our overall understanding of charity effectiveness.

Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

To evaluate a charity’s track record, we consider how well the charity has executed previous programs. We also consider the extent to which these previous programs caused positive changes for animals. Information about a charity’s track record helps us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments—information that cannot always be incorporated into the criteria above. An organization’s track record can be a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences in other important factors.

Have programs been well executed?

CAS is a young organization; they officially launched in early 2018.35 They have already achieved some promising accomplishments, even though their track record is much shorter than the track records of established groups. Their primary long-term outcomes—developing and supporting cultured meat technology and promoting consumer acceptance—will likely take time to yield tangible results.

Still, in their first few months, CAS’s accomplishments include working with GFI to develop the first-ever university course on clean meat, which they report will be running in the upcoming academic year at Stanford University.36 While it seems that GFI has had the more substantial role in the process—such as organizing and teaching the course—CAS made some important early contributions that led to the course’s development.37 They’re also looking to have a similar course at Harvard University, and they report promising conversations with the administration there38 (though we are unsure at this time whether or not the course will take place). They report being invited for multiple speaking engagements across the U.S. and Europe, including guest lectures at prestigious institutions such as Harvard University and City, University of London. Finally, CAS also reports that—in collaboration with partners—they have helped match investors, advisors, and employees to early-stage cultured meat startups, and have assisted startups with company naming, design needs, and general counsel.39

While there is evidence that CAS has executed some of their programs well, we are concerned that they are pursuing a relatively large amount of programs at present.40 Some of those programs seem noticeably less impactful than their other activities that could cause significant reductions in the consumption of farmed animal products. For instance, their Byproduct Initiative and their Children Initiative could affect relatively small numbers of animals. That said, they’ve expressed their understanding of the benefits of narrowing their focus and they report that they are making changes accordingly.41

It is difficult to evaluate CAS’s potential by relying solely on the limited information about their very short history. On the one hand, they certainly report some promising accomplishments in a short time frame. On the other hand, their focus seems unclear—and we think they may be both too funding-constrained and too talent-constrained to successfully execute the number of projects they currently have underway. While some of CAS’s initial activities seem quite promising, the short length of their track record means that there is greater uncertainty associated with donations to CAS relative to more established groups that perform similar work.

Have programs led to change for animals?

CAS’s theory of change is based on achieving medium- and long-term change for animals, and many of their accomplishments have not yet led to changes for animals. Their earliest actions (e.g., contributing to courses and textbooks) will affect animals only indirectly, and their impact will be exclusively medium- or long-term. Since they work to foster the field of cultured animal product development rather than developing individual products themselves, any impact they have will happen through the work of others who they supported.

It is possible that CAS has indirectly benefited animals through their work to gain media attention for themselves and for other groups working in their field. Articles about cultured meat often touch on some of the problems with the existing meat industry. When speaking to the media, CAS has raised concerns about animal welfare in the meat industry and the industry’s unsustainability. In addition to promoting awareness of cultured meat, it’s possible that these media stories have inspired some readers to reduce their meat consumption. On the other hand, some animal advocates are concerned that the messaging of cultured meat companies could reinforce the notion that we need to eat animal flesh, and this could slow down the rate of progress—especially if cultured meat technologies fail to become cost-competitive.42

CAS estimates that cultured meat could become cost-competitive with conventional meat in less than a decade.43 The Open Philanthropy Project (Open Phil) reports that one of two scientists they spoke with who work on tissue engineering gave a similar estimate—though Open Phil themselves remain much more pessimistic about the timeline for the widespread commercial availability of cultured meat.44 We are not certain whether it is realistic to expect cultured meat to become cost-competitive with conventional meat within a decade.45 The timeline is particularly uncertain and often delayed at these initial stages of development as the earliest scientific and regulatory hurdles are tackled. We expect research and funding into this area to grow as the barriers to eventual success diminish, and we think that CAS’s work may speed the commercialization process.

Cost-competitive cultured meat could impact animals by reducing the demand for animal products. Plant-based dairy products such as milk continue to take market share from the sales of conventional milk in the U.S., with sales in the former category growing as sales in the latter category decline.46 It seems likely that cultured meat products will have similar effects—sometimes replacing plant-based products, but also replacing products of animal agriculture—particularly because they will likely be harder to distinguish by taste and texture than current substitutes.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

A charity that has systems in place for assessing their programs is better equipped to move towards their goals effectively. By conducting self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs, and modify or end those that are less successful. When such systems of improvement work well, many stakeholders benefit: benefactors are inclined to be more trusting and more generous, leadership is able to refine their strategy for achieving their goals, and nonhuman animals benefit more.

To evaluate how well the charity adapts to successes and failures, we consider: (i) how the charity has assessed its past programs and (ii) the extent to which the charity updates their programs in light of those assessments.

Does the charity actively assess areas of success and failure?

At this early stage of their development, CAS appears to have mostly set long-term organizational goals that are plausibly achievable and are relevant to their mission of promoting successful cellular agriculture.47 Of the few specific goals that they reported, most do seem relevant and achievable given their latest accomplishments. For example, they plan to launch a second sister website, “Prospects,” which they aim to use to spread key information about why people should be looking for alternatives to traditional agriculture in the first place. Their plan is for that website to contain more than 30 web pages48 that feature relevant research and empirical claims that would be updated frequently for validity. Provided examples of pages include: overfishing, animal killing, antibiotics, and workers’ rights.49 Specifically, they expressed their wish to publish precise figures that compare cellular agriculture to animal agriculture on relevant issues such as the ones outlined above. Though we predict that this task would be highly challenging, CAS believes this information can pave the way for people to become more interested in cellular agriculture.50

CAS explained that the large number of projects available on their website51 could be helpful in attracting those interested in working on these programs in the future.52 However, we are concerned that this large number of projects could lead to CAS spreading themselves too thin—unless they adequately focus on their most effective programs. Since they are a young organization, they do not have a sufficient track record of assessing and improving on their work. This is not to say that they have not begun tracking their work; they already assess their work to some extent. For instance, they recently launched a sister website that complements their main website, in hopes that it can educate the public about how clean meat is produced, why there is a need for it, and what its advantages are.53 They reported that this sister site was getting 50 to 100 views per day, which they believe translates to about 20,000 to 30,0000 views per year.54 Their recent partnership with Google Nonprofits and the Harvard Innovation Lab, however, gives them confidence that their views will significantly increase once they improve on search engine optimization.55

Relatedly, they admit that it could be argued that increasing search engine optimization would have been a more effective use of their past time and resources56 compared to creating a university course. They believe, however, that creating a highly visible product (such as ivy league courses) could end up drawing more attention to clean meat and cellular agriculture in both the short and long term.57 They added that this thought process illustrates the kind of weighing of pros and cons that they tend to do when determining which activities to engage in.58

More generally, CAS appears to be aware of the strengths and challenges of their work. They tell us that their challenges include building strong team unity when most of their staff work part-time, and securing funding for their programs.59 They also report that one of their major strengths lies in the excellent people they have working with them, including their core staff, fellows, and advisors.60 It is our understanding that CAS’s relationship with GFI also represents a major strength; CAS views this relationship as critical to their decision-making process;61 they report benefiting greatly from such relationships, and from the advice and guidance of veterans from the field (such as Bruce Friedrich).62 They have indicated that they intend to hire a core group of people to make up the CAS team, especially because they plan to launch big projects soon.63 They added that they are hoping to learn a lot from GFI in this area, given how they have been able to scale up their staff in just a couple of years.64 This hints at their intention to recognize and capitalize on their strengths. We believe that another one of CAS’s strengths is their well-designed online presence,65 which provides them with an attractive platform to showcase their programs and support an international movement. The professional and credible appearance of their online presence would likely have a positive impact on viewers’ impressions of the content, and as a result would potentially have a positive effect on viewers’ support of cellular agriculture.

Does the charity respond appropriately to areas of success and failure?

Because they consider themselves to be part of the effective altruism (EA) movement,66 CAS reports a strong emphasis on using the framework of importance, neglectedness, and tractability to prioritize their programs.67 They have also demonstrated that they value cost effectiveness. For example, they reported that they were considering hiring specialists in certain domains (such as, for example, communications and law). However, they claimed that it is possible that it would be more cost-effective to simply contract agencies in those domains whenever they need that kind of work done.68

CAS reports having a system in place that they refer to as the “CAStandard,” which states that any CAS-generated content has to be of a very high standard/quality.69 The concept of the “CAStandard” is in place because of their concern that cellular agriculture may face pushback from multiple angles in the coming decades.70 As a result, they believe the field should produce nothing less than excellence—in order to hopefully curb such opposition.71 They therefore seem appropriately aware of the fact that cellular agriculture is a potentially fragile concept that needs to cultivate positive perceptions to ensure its success. More broadly, the “CAStandard” indicates that CAS is mindful about the potential opposition in their field of work, and that likely renders their approach both vigilant and ambitious (we believe reasonably so). Relatedly, they report needing to be flexible with their current areas of focus, which may change as the field changes.72

Generally, CAS appears to have responded to their mission’s challenges by trying to maintain high standards in their plans. For example, they are creating a volunteer platform called C3, and to generate interest in this program they are working with a division of the U.N.73 Given how they believe that a high level of excellence is necessary, it seems likely that they would be determined to remain vigilant about assessing areas of success and failure and improving on these areas whenever possible. They also report already correcting their work and changing some of their approaches in response to new information. For example, they claim that they funded academic natural science research but then realized that the utility of funding this is so low that it is no longer in their domain of interest.74 Finally, CAS Director Kristopher Gasteratos mentioned that he recently took some advice from Lewis Bollard (of the Open Philanthropy Project), who suggested that it would be helpful for CAS to focus on fewer projects in terms of programming.75 Relatedly, they have recently cancelled plans to launch a podcast and to start an academic journal for cellular agriculture, instead concentrating their efforts on the editing of their textbook. It is our hope that any projects CAS chooses to focus on will be accompanied by well-defined goals,76 which would help them track and optimize their future work.

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

A charity is most likely to be effective if it has a well-developed strategic vision and strong leadership who can implement that vision. Given ACE’s commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we generally look for charities whose direction and strategic vision are aligned with that goal. A well-developed strategic vision must be realistic to manage and execute. It is likely the result of well-run, formal strategic planning; when a charity’s leaders regularly engage in a reflective strategic planning process, revisions and improvements to the charity’s strategic vision are likely to follow.

Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-composed board?

The founder and President of the Cellular Agriculture Society is Kristopher Gasteratos, a former cellular agriculture Researcher at Harvard University. While Gasteratos has significant experience as a Researcher, he has little experience as a manager. Nevertheless, CAS staff have told us in private communication that he is learning quickly about leading an organization, and that he is approachable and receptive to feedback.

CAS currently has a board of twelve advisors. Their board size is in line with U.S. best practices, which suggest a minimum of five Board Members.77 Gasteratos tells us that CAS is actively seeking Board Members with diverse occupational backgrounds.78 The evidence for the importance of board diversity is somewhat stronger than the evidence recommending board sizes of five or greater, in large part because there is some literature indicating that team diversity generally improves performance.79 However, to our knowledge, the evidence of the impact of board diversity on organizational performance is less strong than the evidence of the impact of team diversity.80

Our impression is that CAS’s board is involved in the organization’s decision making, but rather informally. Gasteratos tells us that CAS leadership has conversations with the board about planning and strategy, but that CAS operates as a meritocracy in which everyone’s input is valued according to their level of expertise.81

Does the charity have a well-developed strategic vision?

Does the charity regularly engage in a strategic planning process?

CAS does not yet have a formal strategic plan, though they did share a document with us that outlined the top five projects they plan to explore. Since they are still relatively young, they are still developing their strategy. As CAS develops and clarifies their priorities, we believe they would benefit from a regular strategic planning process.

Does the charity have a realistic strategic vision that emphasizes effectively reducing suffering?

CAS’s strategic vision is to accelerate the commercialization of animal agriculture products as effectively as possible.82 They are guided by the principles of effective altruism. Their strategy is motivated by the aim of effectively improving the world by reducing the suffering caused by animal agriculture.83 CAS may shift their programs as the field of cellular agriculture evolves,84 but we find it unlikely that they will shift away from their motivation to effectively reduce suffering.85

Does the charity’s strategy support the growth of the animal advocacy movement as a whole?

Given their focus on promoting the field of cellular agriculture research, much of CAS’s work does not have a direct bearing on the work of other animal charities. Still, CAS is contributing to a neglected and potentially high-impact area. We think that promoting the field of cellular agriculture research may complement the work of animal advocacy charities in the long term, since creating a supply of alternatives to animal products may make advocacy for dietary change more successful.

We are less clear on whether and how CAS’s work supports other groups who are also working on cellular agriculture, in part because CAS is so new. However, we know that Gasteratos engages in conversations with the leadership of other groups, including Bruce Friedrich of The Good Food Institute and Mike Selden of Finless Foods.86 We expect CAS to continue to take a collaborative approach moving forward.

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Effective charities are generally well-managed on an operational level; they should have healthy cultures and sustainable structures. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about their human resources policies and their perceptions of staff morale. We also speak confidentially with non-leadership staff or volunteers at each charity to solicit their perspectives on the charity’s management and culture.87 Finally, we send each charity a culture survey and request that they distribute it among their team on our behalf.88, 89

Does the charity have a healthy culture?

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly towards all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. One important part of acting responsibly towards stakeholders is protecting employees from instances of harassment and discrimination in the workplace. Charities that have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, since varied points of view improve a charity’s ability to respond to new situations.90 A healthy charity is transparent with donors, staff, and the general public and acts with integrity; in other words, their professed values align with their actions.

Does the charity communicate transparently and act with integrity?

Given that CAS has only been active for a few short months, we have very little information on their transparency or integrity.

Does the charity provide staff and volunteers with sufficient benefits and opportunities for development?

All staff currently work for CAS pro-bono, in addition to other (often full-time) jobs. CAS does not provide benefits or formal staff development opportunities for their team.

Does the charity have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion?

Gasteratos runs CAS as a meritocracy; he values staff input according to their skills and expertise.91 CAS staff appear to be well-aware of this fact; several of them mentioned it in their responses to our survey when we asked about CAS’s attitude toward diversity and inclusion. In one sense, meritocracies may seem less likely than other organizations to discriminate unjustly; organizations that make hiring and organizational decisions based solely on their employees’ skills are therefore not making those decisions based on their employees’ race, gender, age, or other personal characteristics. However, we believe that all organizations can gain from actively welcoming a diverse workforce, which may include seeking out talent that is gender-diverse, racially diverse, and politically diverse, among other forms of diversity. Focusing only on people’s existing skill sets risks excluding people who could add tremendous value to an organization but who may not have had an opportunity to develop certain skills yet.

Does the charity work to protect employees from harassment and discrimination in the workplace?

We are not aware of any instances of harassment or discrimination at CAS, though we recognize that there are numerous reasons why we might not be privy to such information if it does exist, and are therefore cautious not to take this lack of information as evidence that CAS is free of any issues with harassment or discrimination. To our knowledge, CAS does not have formal policies in place to protect staff from harassment or discrimination, nor do they provide trainings on these issues. Several respondents to our culture survey noted that trainings seem unnecessary, as CAS operates entirely remotely. However, we think that CAS could benefit from such trainings even if (and perhaps because) their staff doesn’t see the need for them. Harassment can happen even in remote organizations, and we feel that CAS could benefit from putting more formal systems in place to protect their staff.

Does the charity have a sustainable structure?

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in which current leadership might move on to other projects. The charity should seem unlikely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, they should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

Does the charity receive support from multiple and varied funding sources?

CAS launched with a budget of just $15,000 before receiving a $50,000 grant from CEA’s EA Fund for Animal Welfare. Since the grant makes up a large majority of CAS’s funding, we think CAS should focus on developing a larger base of individual donors to ensure its financial sustainability.

Does the charity seem likely to survive potential changes in leadership?

CAS is quite a young organization and is still establishing its strategy and operations. In one sense, a change in leadership at this time could dramatically change the future of CAS. In another sense, a change in leadership for such a young organization might be less disruptive than a change in leadership for more established organizations.

,Lower estimate,Upper estimate High Priority,630000,770000 Low Priority,140000,280000

“We have been working with the Good Food Institute (GFI) to develop the first-ever university course on clean meat, which will be running in the upcoming academic year at Stanford. We are now looking into running a similar course at Harvard next summer and have had promising conversations with administration there.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

“We’re finalizing the contract now with Elsevier and then will begin contacting the dozens of authors/reviewers […The] deal seems 99% done.” —Private communication with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society, 2018

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

Between 2010 and 2015, plant-based milk sales (particularly almond milk sales) increased, while the total milk market shrunk by over $1 billion in the U.S., according to Nielsen. According to more recent research by Mintel, between 2012 and 2017, non-dairy milk sales grew by 61% while dairy milk sales fell by 15%.

“In collaboration with CAS Partners, we have helped match investors, advisors, and employees to early stage clean meat startups, assisted startups with company naming, design needs, and general counsel.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

“We are currently looking into what clean meat facilities should be called (as opposed to the term “slaughterhouse” for traditional meat production). […] [W]e are simultaneously working on developing a realistic simulation of a clean meat facility. There currently aren’t any high quality stock images to represent cellular agriculture at media releases and presentations to companies.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

See the 80,000 Hours article “Presenting the Long-Term Value Thesis” for a more detailed discussion of why long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.

“When outcomes of interventions are interdependent, the effectiveness of each is inextricably linked with those of the others. Justifying one as being more effective than another is not quite straightforward—declaring so is often misleading.” —Sethu, H. (2018) How ranking of advocacy strategies can mislead. Humane League Labs.

See our report on leafleting for a more detailed consideration of the potential long-term impact of a particular intervention.

A 2017 study found that, while most participants said they were willing to try cultured meat, only a third of participants said they would probably be willing to regularly eat cultured meat or eat it as a replacement for meat from slaughtered animals. In 2018, a poll by GFI and Faunalytics, funded by ACE, found that two-thirds of Americans are willing to try cultured meat grown from cells without slaughtering animals. A majority were willing to eat cultured meat as a replacement for conventional meat. Forty percent said they would pay a premium for cultured meat.

For a discussion of some of the difficulties in predicting the cost-competitiveness timeline, see ACE’s report on the cost-competitiveness of cultured animal products.

This information can be found in the June 2018 Animal Welfare Fund Update.

Private communication with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society, 2018

This information can be found in Follow-Up Questions for Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

This information can be found in the Follow-Up Questions for the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

Private communication with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society, 2018

This platform, called C-Cubed, aims to support project and idea development and connect members to volunteers and activists.

“We are also looking into creating a second sister webpage, which will be called the “prospects” […] where users can go to learn about different problems related to animal agriculture […] paving the way for people to become more interested in cellular agriculture.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

“There are currently 17 programs listed on our website. We make all of these programs available online in case someone who may be interested in working with us in a particular area comes across our website. […] But we don’t plan on truly working on all of these right now: the focus for the near future will be specifically on the divisions of high importance with an emphasis on media, design, social science, and legal.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

Private communication with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society, 2018

This range is a subjective confidence interval (SCI). An SCI is a range of values that communicates a subjective estimate of an unknown quantity at a particular confidence level (expressed as a percentage). We generally use 90% SCIs, which we construct such that we believe the unknown quantity is 90% likely to be within the given interval and equally likely to be above or below the given interval.

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for Cellular Agriculture Society.

The method we use does calculations using Monte Carlo sampling. This means that results can vary slightly based on the sample drawn. Unless otherwise noted, we have run the calculations five times and rounded to the point needed to provide consistent results. We did this by first rounding the 5% and 95% estimates given in Guesstimate to the nearest $10,000 and then taking the most extreme of the five estimates (the highest value for an upper bound and the lowest value for a lower bound) and rounding it outwards to the next $100,000 when the numbers are in the millions and to the next $10,000 when the numbers are in the tens or hundreds of thousands. For instance, if sometimes a value appears as $2.7 million and sometimes it appears as $2.8 million, our review gives it as $2.9 million if it were an upper bound and as $2.6 million if it were a lower bound.

For example, they suggested focusing on social science research projects, which are relatively neglected and not also taken on by the for-profit sector (as some of the relevant natural sciences projects are). This information was provided in a private communication with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society in October 2018.

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for Cellular Agriculture Society.

For example, they are doing some work related to cellular agriculture of rhino horns—this work may impact relatively fewer animals than efforts to accelerate the development of cultured meat. This information can be found in our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

The percentages used in this chart are based on the mean size of each funding gap.

“In the future, we could almost certainly benefit from even more funding, but given our success up to now with a conservative budget, it makes sense to stick to that frugality as much as possible and develop slowly rather than try to build too much too fast.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

“The minimum that we could use is a low-to-mid 6-figure budget, and there likely wouldn’t be a maximum to what we could use.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for Cellular Agriculture Society.

This estimate is an SCI based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for Cellular Agriculture Society.

We have sometimes prepared, but not published, speculative estimates similar to the one we could have prepared for CAS.

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

Private communication with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society, 2018

For more information, see The Cellular Agriculture Society’s Accomplishments (2018).

For more information, see The Cellular Agriculture Society’s Accomplishments (2018).

At the time of writing their website lists 17.

“In terms of programming, I recently took some advice from Lewis Bollard, who suggested that it would be helpful to focus on fewer projects. Even though I often want to complete as many projects as possible in a given year, we will be aiming next year to focus on a smaller number and make each of them as good as they can be. There are currently 17 programs listed on our website. We make all of these programs available online in case someone who may be interested in working with us in a particular area comes across our website. This way, they know we run (or at least plan to run) programs in that area and they can reach out to us. But we don’t plan on truly working on all of these right now: the focus for the near future will be specifically on the divisions of high importance with an emphasis on media, design, social science, and legal.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

See, for example, this video featuring animal advocate Casey Taft.

“I think the time to wide-scale commercialization ought to correlate with the quantity of funding, as I agree, much will happen outside of NGOs. So if it was 100 years away, no, I don’t think this would be a productive use of EA funding, though I also highly doubt this will be the case, and because it’s probably less than a decade away and funding (not particularly significant) can help accelerate this timeline, this indeed could be a productive funding area.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

See Open Phil’s write-up of their investigation of animal product alternatives. Note that we do not know the identity of one of the scientists, nor are we fully aware of the considerations that informed the scientists’ estimates.

To better understand our reasoning about cost-competitive timelines please see our report titled “When Will There Be Cost-Competitive Cultured Animal Products?”

Between 2010 and 2015, plant-based milk sales (particularly almond milk sales) increased, while the total milk market shrunk by over $1 billion in the U.S., according to Nielsen. According to more recent research by Mintel, between 2012 and 2017, non-dairy milk sales grew by 61% while dairy milk sales fell by 15%.

When considering how well charities assess success and failure, one useful consideration is whether their goals are SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. Specific, well-defined goals help guide an organization’s actions, and can help them determine which areas or programs have succeeded and failed. Setting a measurable target allows organizations to determine the extent to which they’ve met their goals. It is also important that goals be plausibly achievable; goals that are predictably over- or undershot tell an organization little about how well their programs have done. Goals should be relevant to the organization’s longer-term mission, both to guide their actions and to help them evaluate success. Finally, including time limits is especially important, as it keeps a charity accountable to their expectations of success.

“Research on cellular agriculture is currently decentralized, ranging from general arguments against animal agriculture found on animal rights organizations’ websites to scattered literature found among CAS, GFI, NH, etc. The Prospects pages aim to create a central database that will answer the question, “What are the prospects of cellular agriculture?” —CAS Programming Outlook

For more information, see the CAS Programming Outlook.

“We hope that this will help spread information about why we should be looking for alternatives to traditional agriculture in the first place, paving the way for people to become more interested in cellular agriculture.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

At the time of writing, their website lists 17 programs.

“There are currently 17 programs listed on our website. We make all of these programs available online in case someone who may be interested in working with us in a particular area comes across our website. This way, they know we run, or at least plan to run, programs in that area, and they can reach out to us. But we don’t plan on truly working on all of these right now[.]” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

“… as this could educate a greater quantity of people about cellular agriculture.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

“Another crucial strength of CAS is the excellent people we have on our staff. Most of our board works on a pro bono basis, and they are all highly invested in the field. Outside our core team, we have many external partners and advisors that are helpful to us on a daily basis.” Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

“[…] we would still want to have a core group of people making up the CAS team, especially with some of the big projects that we have coming up. We are hoping to learn a lot from GFI in this area, given how they have been able to scale up their staff to a team of 50 in just a couple of years. So, having funding in the low-to-mid six-figure range would enable us to hire and retain this core staff and then expand from there. […] the focus for the near future will be specifically on the divisions of high importance with an emphasis on media, design, social science, and legal.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

To our knowledge, this includes their main website Cellag.org (which includes their volunteer portal, C3), their first sister website (Cleanmeat.info), and their upcoming second sister website (Prospects).

“As developers and promoters of cellular agriculture, we have the potential to offer the kind of panacea that animal rights advocates are looking for. To this end, we’re working on a lot of novel projects and we subscribe as much as possible to the effective altruism framework to ensure that our work is having maximal impact and that every one of our actions leads to some kind of commercialization.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

“There are multiple factors that play into the strategy (…) an EA calculus is basically used in our decision making (…) for example: How important is this program to advance cell-ag? If it’s very important, is anyone else doing it? (…) If (…) it [is already] being done as effectively as possible well then let’s find the next most high-impact area that is also novel/neglected that will advance cell-ag. How tractable is a program to making progress for a particular area?” —Follow-Up Questions for Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

“For instance, we once (early on) funded academic natural science research but then realized that the utility of funding this is so low that it is no longer in our domain of interest. (This is because the hundreds of thousands of dollars allocated to natural science research thus far will likely result in virtually no benefit to actual product commercialization, besides scientist preparation for industry. We are therefore not interested in allocating human/financial resources towards something that does not advance commercialization significantly).” —Follow-Up Questions for the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

For more information, see our Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018).

When considering how well charities assess success and failure, one useful consideration is whether their goals are SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. Specific, well-defined goals help guide an organization’s actions, and can help them determine which areas or programs have succeeded and failed. Setting a measurable target allows organizations to determine the extent to which they’ve met their goals. It is also important that goals be plausibly achievable; goals that are predictably over- or undershot tell an organization little about how well their programs have done. Goals should be relevant to the organization’s longer-term mission, both to guide their actions and to help them evaluate success. Finally, including time limits is especially important, as it keeps a charity accountable to their expectations of success.

See these three standards for nonprofits in the U.S. suggesting between five and seven Board Members as a minimum.

“The most significant change we’ve had recently was a change in the constituency of our Board of Directors. We found that a number of our Board Members were becoming actively involved in the clean meat and cellular agriculture industries in their full-time work, and it is important to us to keep our board as impartial as possible. We are in the process of changing some members of our board, bringing in new people who are less professionally involved in these industries to replace those who have become more involved.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

“[T]here is a significant body of evidence suggesting that teams composed of individuals with different roles, tasks, or occupations are likely to be more successful than those which are more homogeneous. Increased diversity by demographic factors such as race and gender has more mixed effects in the literature, but gains through having a diverse team seem to be possible for organizations which view diversity as a resource (using different personal backgrounds and experiences to improve decision making) rather than solely a neutral or justice-oriented practice.” —ACE Blog: “How Should we Evaluate Organizational Factors that Affect Charity Performance?”

Board demographic diversity in for-profit organizations has been found to be positively correlated with better financial performance. Nonprofit board diversity (in terms of occupation and age) has been found to be positively associated with better fundraising and social performance, better internal and external governance practices, as well as with the use of inclusive governance practices that allow the board to incorporate community perspectives into their strategic decision making.

“We always have conversations about our planning and strategy with the Board of Directors. We operate as a meritocracy, where I make sure to take everyone’s input into account and then we go with what seems like the best approach from the person who has the most expertise in the relevant area.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

“To put this bluntly, the strategic plan is literally: “Ensure all efforts at CAS lead to the acceleration of cellular agriculture commercialization globally as quickly and successfully as possible.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

”This strategy exists to to address (effectively altruistically) the problems animal agriculture presents.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

“Our programming hinges entirely on this mission/strategy and as noted in our call, may change as the field changes.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

When we asked whether CAS supports work on other cellular agriculture products—aside from cultured meat—Gasteratos replied: “[W]e do, but only if it aligns with our EA vision and helps people/animals/[the]world. […] I understand though (and have heard rumors) as to why other organizations may support entities like [flower fragrances or leather alternatives], for political reasons, etc. but I’m just disinterested in sacrificing the EA values of CAS.” —Follow-Up Questions for the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

“As mentioned earlier, we work particularly closely with GFI, and we have benefitted from advice and guidance from veterans of the field like Bruce Friedrich. Just last night, I was speaking with Mike Selden of Finless Foods and getting his feedback and suggestions regarding our upcoming textbook project.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)

We speak with two non-leadership staff or volunteers at each charity, except when doing so would not allow us to preserve the anonymity of our contacts (i.e., when charities have fewer than four staff members). Our selections of contacts are random in all dimensions except the following: we aim to select staff members or volunteers who have been with the organization for at least one year (when possible), and we aim to speak with at least one woman and/or person of color from each organization (when possible). To protect our contacts’ confidentiality, what we learned in these conversations is paraphrased in the review, and references to these conversations are identified only as “Private communication with an employee of [Charity], [Year].” For more information, see our blog post discussing this change, which we implemented in 2017.

We recognize some limitations of our culture survey. First, because participation was not mandatory, the results could be skewed by selection bias. Second, because respondents knew that their answers could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer, they may have felt an incentive to emphasize their employers’ strengths and minimize their weaknesses.

There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that teams composed of individuals with different roles, tasks, or occupations are likely to be more successful than those which are more homogeneous. Increased diversity by demographic factors—such as race and gender—has more mixed effects in the literature, but gains through having a diverse team seem to be possible for organizations which view diversity as a resource (using different personal backgrounds and experiences to improve decision making) rather than solely a neutral or justice-oriented practice.

“We operate as a meritocracy, where I make sure to take everyone’s input into account and then we go with what seems like the best approach from the person who has the most expertise in the relevant area.” —Conversation with Kristopher Gasteratos of the Cellular Agriculture Society (2018)