ACE Interviews: Hal Herzog

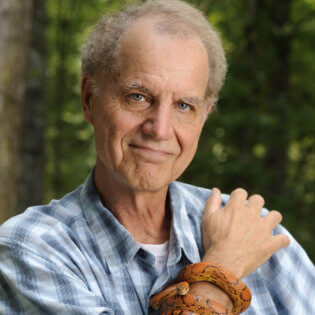

Hal Herzog is a professor at Western Carolina University, which is in the Smoky Mountains of North Carolina. He’s a psychologist who has been studying human-animal interactions for the last thirty years. He’s the author of the book Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It’s So Hard To Think Straight About Animals. Hal spoke with Diana Fleischman, also a psychologist and author of The Sentientist blog, and Allison Smith, ACE’s Director of Research.

Diana Fleischman: You wrote an essay called “In Defense of (Some) Meat”, and in your book you seem to also make allowances for “hypocritical” behavior. Could you summarise your stance on eating meat from the essay and your book and talk about whether or not your views have changed?

Hal Herzog: In some ways my views have changed in recent years and in some ways they haven’t. I wrote that essay, “In Defense of (Some) Meat,” as sort of an intellectual exercise. The New York Times runs a column called “The Ethicist”, and the woman who was “the ethicist” at the time felt that there had been tons written on what’s wrong with eating meat, and the arguments are very persuasive, but nobody ever writes in defense of eating meat. So she organized a contest, and I, along with 3,000 other people, submitted an essay defending eating animals.

At first I thought of it as a joke and then I decided it was an interesting intellectual exercise: could I come up with a reasonable defense of eating meat. And after thinking about it for a couple of days, I wrote the essay. First, I need to say that I am convinced that the arguments against eating meat are much stronger than the arguments for eating meat. So the question for me was, could I come up with something that would be possibly convincing; but also funny, because that’s what I do; and because that would also get people to think. So what I asked was are there any situations in which it would be okay to eat animals? And I came up with three. The first one was eating animals that are dead. In that category I put roadkill; it’s okay to scrape things up from the road and eat them because they’re already dead. I also included animal shelters because I was in my Jonathan Swift guise, and where else can you get ready supplies of dead animals. We kill three to four million dogs and cats a year in the United States. Why not eat our dead pets? No harm is going to be done there.

The second category I included was animals that have such rudimentary nervous systems that I didn’t think they could feel much pain or pleasure. In that category I put insects, jellyfish and oysters. Even Peter Singer famously drew the line somewhere between the shrimp and the oyster. So I said, I’ll go along with that, somewhere between the shrimp and the oyster.

The third category is probably the one that would be the most controversial, and actually the most realistic. This would be animals that are absolutely humanely treated and die a humane and virtually instant death. That is, the lights simply go out for these animals. That’s a very hard thing to pull off, but it can be done. I know of places where animals have a very happy life and are killed with no fuss, bother, etc. And I eliminated hunting. Hunting is a situation where, if it’s done right, the lights simply go out. But too often the hunter wounds the animal before it dies, and there’s suffering. So I decided hunting’s not allowed in my system. But I lost the essay contest; I was one of the 2,999 losers.

Fleischman: For what it’s worth, I actually thought your essay was way better than the winning essay. I don’t agree with you very much about the final category, the humane category, but the others I largely agree with. I’ve seen you post on Facebook about stuff that you’re eating; what about your personal habits?

Herzog: I’m not a vegan and I’m not a vegetarian; I guess I’m what you’d call an omnivore with a conscience. In recent years I have changed my diet somewhat—I eat less meat. I probably eat 50% of the meat that I used to. And I go through the motions; I pay more for animals—for carcasses—that are raised locally on farms, and other things like that. If the eggs’ packaging says anti-cruelty on it, I buy it and pay more. I know enough about these labels to know they don’t mean much, but, like I said, I’m going through the motions.

Fleischman: In your book and in your blog you’ve talked about the disparity in consideration/funding for companion animal causes, protests against biomedical research and animals on farms. This is also something that’s been talked about a lot more recently. Do you think it’s important to close the gap in the importance people place on these different causes? Do you have any idea about what would be effective to this end?

Herzog: I think you’re not going to like my answer to this question. Is it important to me to close the gap? No. In fact I relish the gap. That’s because I’m a psychologist, and I look at these issues, and how people struggle with them, as a window into larger issues in human nature. If I were an animal activist, I think I would care about trying to close that gap. But that’s not my agenda.

My agenda is to conduct research in such a way as to shed light on how people can be so inconsistent in their lives. By the way, I try not to use the word “hypocrisy” very much. I think on some level we’re all hypocrites, and that word is just a little too negative. I think we all have to struggle with these paradoxes, and I relish the paradoxes in my own way. So I’m not on a mission to change people’s lives and their behavior. I am on a mission to get people to think more deeply about these issues. So if I can do that through my blog or through my book, I’m happy. This is the same approach I take as a college professor. My classes are most successful when the students walk out with more questions than they walk in with. My agenda is to get people to identify things that they had not thought about before and put more thought into them. Does that make sense?

Fleischman: I think it does. You’re saying that your motivation is intellectual curiosity and fostering intellectual curiosity and that you don’t have an ethical agenda as such; that you think that intellectual curiosity is a good in and of itself.

Herzog: Yeah, I do. And I do sort of have an ethical agenda in some aspects of my life; I’m a left-winger and I give money to political causes. But interestingly enough, I don’t do the same thing to animal causes. Because when it comes to animal causes I try and stay above the fray. I think it keeps me honest as a Researcher. Years ago when I was studying rooster fighters, within one week, I had the Kentucky Gamefowl Association, wanting me to go testify in favor of cockfighting before the state legislature, and I told them no. The same week the Humane Society of the United States contacted me, and they wanted to use photographs that I’d taken at rooster fights. I said no to them as well. I had much more sympathy for the Humane Society than I had for the rooster fighters, but I wanted to try to be as objective as possible. We can’t be completely objective, but I’m trying to be as objective as possible. I see that as my role. What’s surprising to me is the number of animal activists, people like yourselves, who have appreciated my position. I thought I was going to be skewered when my book came out. But a lot of animal activists have written me and said, “Thanks. I know you don’t share our views, but you help us a little bit by getting people to think about these issues.” I’m happy for that.

Fleischman: I have to say, I just had sort of an evil moustache-twirling villain in mind when I thought about cockfighters before I read your book. So it was very enlightening to me. Especially that story you told about the man who was exercising the roosters and things like that. I guess the dissonance from before and after made me uncomfortable in a way that I thought you would appreciate.

Herzog: Yeah. It’s funny, because it had been years since I’d hung out with those guys. I went back and re-interviewed them for my book, and it was really interesting to reconnect with them. One of them did ask me to go to a rooster fight with him, but I said no. I wouldn’t do it now. Things that I would have done in a heartbeat thirty years ago, I refused to do this time around.

Fleischman: Recently we talked about studies done recently on vegetarian outreach (The Humane League leafleting study, ACE leafleting study, ACE humane education study). This is a really new area; for example, we still are not entirely sure how much money someone would need to spend on leaflets to convince someone to be vegetarian for the short-term or long term. Do you have any comments on this research? What do you think is the next step in investigating effective outreach with leaflets or otherwise?

Herzog: I have a number of comments. I looked at the studies. In some cases I actually looked at the data sets themselves, and in some cases I looked at the blogs. I was really impressed with the blogs and that for all three studies, you made the data available and you described the studies and their limitations. It was really clear, and I thought the blogs were great.

The studies themselves raised a classic conundrum in the behavioral science: are we going to go for internal validity or external validity? External validity is whether or not your findings apply to the real world. Internal validity deals with the intricacies of experimental design. Is your experiment right from a design point of view, in terms of picking subjects, in terms of randomization, in terms of measuring the right variables? It is technical aspects of the research. Ideally, you want both internal and external validity, but the problem is that oftentimes you can’t have both in the same study. Studies done in the real world tend to be sloppier because it’s the real world. Studies done that have high internal validity often are not very applicable to the real world. That’s because they’re done in laboratories with students and have other similar issues…

For all three studies you opted for the real world. So you gave out fliers to real people in real situations and tried to contact some of those people three months later. You examined people giving lectures in various situations and looked at how that affected behavior. That study was absolutely laudable. However, all three studies ran up against the internal validity issues. There were problems with sizes of control groups, and so you found some really anomalous results. For example, in the Humane League leafleting study, the control group actually showed more behavior change than the experimental group. What you might conclude from that was that your leafleting actually made people change their behavior less. I don’t believe that that really happened, and you discussed that in your report. I also had some quibbles with some of the statistical analysis, but the bottom line is that I pretty much agreed with all your conclusions. Despite the fact that I wasn’t completely comfortable with some of the methods, I thought the studies were ambitious. And I was really impressed that you didn’t try to interpret things to make the results look better than they actually were. So I thought it was an honest attempt and that you interpreted your results honestly. From that point of view I give the research high marks.

One of the conclusions was it’s really difficult to change a lot of people by giving them leaflets. You can change a small number of people, but in terms of larger numbers of people, that’s probably not going to happen. Am I correct in that conclusion?

Fleischman: In my own personal experience, I saw tons of vegetarian leaflets, I saw tons of vegetarian outreach, and then I really reached a threshold where it made a difference to me, but before that I didn’t really care. So I think there has to be sort of a right time and we have no idea when it is. So do you have any ideas about what kinds of research we need to do to find this out? You were distinguishing between internal versus external validity and saying that there should be a controlled version of this kind of study.

Herzog: Yes, I do have a few suggestions. One would be to try to do some things that emphasize the internal validity part of the research. That would involve doing experiments on a smaller scale, maybe using college student samples in order to find out the effectiveness of leaflets or media. Another thing would be to find a social psychologist who is really interested in these issues, someone who has strong methodological credentials and would be interested because they’re personally involved in the issues. There’s a guy named Hank Rothgerber, who’s a social psychologist at Bellarmine University in Kentucky. In the last two years he’s done an incredible series of studies looking at issues like the difference between vegans and vegetarians, and the difference between vegans and conscientious omnivores. There’s been six or a dozen studies that he’s published in really good journals, like Appetite, PLoS One, some social psych journals. I don’t know him personally, though I have read many of his articles. Unlike me I think he probably is vegetarian or vegan and is not just doing his research simply out of intellectual curiosity. There’s another psychologist, Brock Bastian, who I believe is in Queensland whose work is fantastic. I also have the feeling that Brock might be a good collaborator in terms of someone you can talk to about methodology. Again, these guys are good at the internal validity side of research. The ethics of meat-eating has really become a hot area of research right now in psychology. It used to be there was just a couple papers by Paul Rozin.

Fleischman: I think that it’s really good that these things are becoming more evidence based, because there was all kinds of outreach being done, without any clear idea of what kind of impact it was going to have.

Herzog: One of the things I was impressed by in the studies that you did, is that they were honest. I didn’t think you were trying to tweak the data. I feel the same way about Che Green at Faunalytics. I believe their data. Same thing with the Vegetarian Resource Group. They do surveys on vegetarianism that I follow carefully, and I totally believe their data. You guys are activists, but you’re good in that you’ve convinced me that you’re honest brokers and you tell it like it is.

Fleischman: What is some of your favorite research happening right now in the domain of human attitudes/ethics towards nonhuman animals? You were just talking about Brock Bastian and Hank Rothgerber, and there’s been some interesting stuff about dogs recently that’s come out.

Herzog: Number one is that I think my area, anthrozoology, has been marginalized pretty much since I entered it in the mid 1980s. We fall between the cracks in terms of academic departments, and people don’t take animal stuff very seriously. But I think that’s really changing. There are more and more papers on human-animal interactions that are appearing in mainstream journals. Skilled mainstream Researchers are getting interested in these issues. This is a good time to be working on animal issues because there’s a lot of public interest right now.

I’m also interested—this isn’t related to veganism and vegetarianism—in the impact of pets on human health. And I’m the naysayer, I’m the guy that’s saying they’re not as good for you as most other people are telling you. But I think we’re really getting better research on the impact of pets on people and why they’re good for some people and not good for others. That’s because there’s more money available; the National Institute of Health and the Mars Corporation joined together to fund some good research. We’re getting studies with better control groups, larger samples, and good outcomes measures. I think the future’s really bright for the study of human-animal interactions.

Fleischman: Just as an aside, I sometimes think about how many people change their attitudes fundamentally about non-human animals because of a companion animal in some way, shape, or form. Do you think how pets change people’s attitudes is a good line of research? I think that I’ve heard a lot of people say they fundamentally changed their attitudes about animals when they have a dog or a cat die.

Herzog: You’re exactly right. The animals that people interact with the most are the animals they eat. That’s the unfortunate truth. But after that, the animals they interact with most are their pets. And most people have an intuitive sense of what’s going on inside their pets’ heads. I think that if you’re trying to convince people that a chicken is a sentient creature, probably the best way is through their cat or their dog.

Fleischman: What research or ideas from psychology do you think it’s most important for animal activists to be familiar with?

Herzog: I think there’s a couple of areas. The first is some of the work in social psychology, especially the research on dehumanization. Some of the Researchers who are working on how people respond to ingroups and outgroups are applying their theories how we think about other species. Another area is moral psychology. I became interested in moral psychology through the work of Jonathan Haidt through his book The Happiness Hypothesis and his research on disgust and moral judgment. I was interested in the question of “Are animal activists more likely to be disgustable? Does disgust motivate them?” And Lauren Golden and I did a study and found out that this idea was to some extent true. In his latest book, The Righteous Mind, Haidt has some pretty practical tips on how to change attitudes. If you were to ask me what would be the most important, accessible, and useful book in terms of thinking about the best way to change attitudes, I would say The Righteous Mind.

Another book, for folks like yourselves that are actually doing survey research, I would suggest is Don Dillman’s work. I’d never heard of him until I started working with Scott Plous, a really good social psychologist, about 15 years ago. We were designing surveys of individuals serving on university animal care and use committees, and one of the first things Scott said to me was, “well you’ve got to read Dillman.” Dillman has come up with ways of designing effective surveys so that you get very high response rates and the data’s good. In terms of research methodology, I’m a huge fan of Dillman.

Allison Smith: Do you have any specific names of people who are working with the ingroup/outgroup stuff that would be good to look at?

Herzog: Brock Bastian has done work in that area. And he worked with a Researcher named Gordon Hodson. Also Bastian and his colleagues recently had a brief review article in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science that’s a really good 4-5 page overview of what we know about the psychology of meat-eating.

Fleischman: I think I read that, that’s really good. Another thing that I think I would just add is sort of sex differences, so there was a Gallup poll and it showed that the moral issues that divided men and women the most were issues of animals.

Herzog: I saw that poll. It was really interesting, wasn’t it? We’re even seeing sex differences among Researchers who study human-animal interactions. When the International Society for Anthrozoology had their meeting last summer, they had pictures of all the speakers on Facebook. By my calculations, there were four times as many women as men who were speakers at the conference. So this area of research attracts women – just like the animal rights movement itself is more likely to attract women.

Fleischman: In one of your most read blogs “Why Are There So Few Vegetarians”, you say that the campaign to moralize meat-eating has failed. You allude to this being due to “biology”; you don’t mention Steven Pinker specifically, but you talk about how meat is an intrinsic part of our motivational makeup. And Steven Pinker talks in his book about “meat hunger”, the idea that there is a specific kind of motivation or hunger for meat. Would you like to elaborate any more on this?

Herzog: Yes, I would. I sometimes change my mind and I think I was wrong about that. If I were to write my book over again, I would have written that part differently. I’m less convinced now than I was when I wrote the chapter on meat about the biological basis for meat-eating. I think there is a biological basis for meat-eating, but I am now convinced that culture plays a huge role in our consumption of flesh. By the way, I loved writing that chapter. It was the most fun to write because I learned so much. I knew almost nothing about the topic and I just delved into it. It was fascinating.

But the data that I didn’t have at the time was on national differences in meat consumption. I didn’t know exactly how much more meat Americans eat than almost anybody else in the world. I was oblivious to the fact that there are countries in which people eat on average 5-10 kilograms of meat a year and that’s not for health reasons. I’m now impressed with the cultural differences in meat eating. I definitely think I overplayed the biological influence on eating animals.

The other area where I think that I made a mistake is that I resisted acknowledging for a long time that meat consumption is actually going down. I was looking at some new data from the Department of Agriculture last night, and it looks to me like meat consumption in the United States has dropped about 10% in the last 7 years. And that’s a lot!

So here I am on record as saying the campaign to moralize meat has failed – which I think it largely has if you’re looking at the number of animals killed. But something is going on. Bob Dylan’s got that great line that “Something’s happening here, but you don’t know what it is.” Well, I feel that way about meat consumption Something is going on, but I don’t know what it is.

I’m not sure whether our declining meat consumption is due to ethical change or if it’s due to health issues or if it’s due to the economy. We’re seeing the same thing in Europe. But, on the other hand, world-wide meat consumption is going up.

Fleischman: I think there’s something quite interesting going on in terms of decreasing meat consumption, potentially, in Europe and the United States, and it’s increasing with affluence in other places in the world. And if the hypothesis is correct that people in the developing world want to be like people in the West, I’m curious about how that will work out if people in the West start adopting a more vegetarian diet. I had this Indian professor, Devendra Singh, who always said, “Oh, you eat like the poor people in India, and I moved here…”

Herzog: There are some claims I made in my book and on my blog that I am not repentant on. I’m impressed that the number of vegans and the number of vegetarians has stayed pretty stable, as far as I can tell. I’m not seeing a big drop there. The best data is from Vegetarian Resource Group. The problem is that there are so few vegetarians and so few vegans that they inevitably fall within the margin of error; the margin of error of these national polls is usually about 4%, plus and minus. So the latest data from the Vegetarian Resource Group I think is like 4% or 5% vegetarian and then another 1% vegans, but if you take that 1% vegan figure, and you say, well, we have margin of error rate of 4% then we really don’t know how many there are. The other thing we know, and this is something you found in the ACE study, is that half of the vegetarians in that study said that they ate meat sometimes. So it is surprisingly common for vegetarians to eat meat.

Fleischman: That’s very common, absolutely. And people define fish as not meat, as well.

Herzog: They do!

Fleischman: You obviously think that there are some failures of the animal rights movement and animal welfare movement with regard to animals used for food. Do you have any ideas about how the animal rights movement can flourish more going forward or avoid what you perceive as potential failures?

Herzog: I think there are other psychologists working in the area of behavior and attitude change that would probably be better than me at trying to address that question. But I think one thing would be to avoid moral absolutism. I know people that are vegans and vegetarians that are just total absolutists. They think that if you’re not with them all the way, you’re on the dark side. Then there are people like like Bill Clinton who’s going around telling everyone he’s a vegan now, but freely admits he eats fish once a week. It would be real easy to make fun of Bill, and I have. But the thing is, the guy is trying. So I’m a fan of things like Meatless Monday. I’m a fan of Mark Bittman’s idea of “vegan until 6 PM” and then you’re allowed to eat meat. I know that there’s people that would say, “No, you’ve got to go all the way or else you’re—you’re harming animals.” But I think that thinking puts people off. To me it’s a balancing act. I think to encourage people to take small steps is often the best way to go.

Fleischman: I think that’s a difficult question as well. I think that previously vegetarian may have been more strictly defined. But if people are defining themselves as vegetarian or vegan and eating fish on a regular basis or eating meat occasionally, then I’m not sure how much absolutists are really going to make a difference, if people are already defining themselves however they want.

Herzog: Well, there’s other things too. What I think most people want is to be happy and to lead a good life. And sometimes moral clarity gets in the way. One of the first studies I did was an investigation of the psychology of animal activists. It was a qualitative study in which I interviewed several dozen animal activists. I had just finished a study of cockfighters, and I wanted to see what people were like on the other side of the moral divide. I knew what cockfighters were like, but I didn’t know what animal activists were like.

What I found is that some of the animal activists were absolutely happy, happy in the way that fundamentalist Christians are happy. Happy in the sense that they had found a truth, that they were spreading the word, and that they had brought their behaviors in line with their beliefs. Those activists really had their act together. But I found other activists who were not happy at all. And they were struggling with their own, even minor, moral lapses. Their social life had gone to hell. I remember one young female activist who told me “You know, I’ve quit trying to date.” And then she said, “Just going out for dinner becomes an ordeal.” I’m sure you have had those experiences where, let’s say, you’re vegan or vegetarian and your friends are not. And so, are you less likely to get invited over for dinner because your friends don’t know what to make? So I think there’s a downside to moral clarity. Does that make sense?

Fleischman: Absolutely, that absolutely makes sense. I think social pressures are a difference and I’ve definitely had people say to me, “I really agree with your ethics, however I’m afraid of what would happen to my social sphere or my social life if I had more moral clarity or if I brought my behavior more in line with my beliefs.”

Herzog: Well that’s a real fear. I talk with people about that, and they say, yes, it impacts their social life. Not everyone says this, but some people do.

Fleischman: Absolutely.

Herzog: But on the other hand, there’s another social group that you can have when you don’t eat meat.

Fleischman: Yeah, that’s definitely in line with my experience.

Fleischman: Considering the far future, do you foresee an end to animal use? Do you think, as some do, that our descendents will be appalled that we ever ate meat?

Herzog: That’s a good question and I think that is a possibility. I have high hopes for in vitro meat. I think it was really smart of PETA to do that that million dollar challenge where they would give a million dollars to the first group that could make an in vitro (petri dish) hamburger. I don’t agree with everything PETA does, but I thought that was a good idea. I would love to go to the grocery store and buy a hunk of tasty flesh that was never part of an animal. I have some hopes for artificial meat.

In terms of changing people’s moral codes, that’s a tougher one. I think maybe in the far future, but not in the near future. I don’t see the number of vegetarians rising dramatically in the next ten or fifteen years.

Fleischman: I think that if you make becoming vegetarian completely cost free, so that you don’t have to sacrifice anything, then I think people are going to be vegetarian much more often.

Herzog: I think that’s absolutely true. But the stuff also has to be tasty. In the New York Times this week, Melissa Clark has a nice video on a vegetarian burger she has developed. She swears it is absolutely delicious, and it looks delicious. However, you should see what she had to do to make that. The burger probably has 20 or 30 ingredients in it, and if you were gonna buy the ingredients from a store, it would probably cost you 30 bucks for a faux hamburger. Then there would be the hours in the processing and cooking. It would be great if this fake meat were readily available, tasty, and cheap. But right now, it is not.

I mentioned in vitro meat. But I also have high hopes and I mean this seriously, for insect based food.

Fleischman: You mean insect farming like the startup Little Herds.

Herzog: Yeah, to me they’re the perfect food animal because they would love (I suspect) the horrible conditions in chicken factory farms. That would be heaven for a meal worm. I am definitely on the side of insect farming. There may be a moral cost, but I’m not sure I see it. There is a cost to veganism too; the number of insects and small animals that are killed because of corn farming and plant agriculture. You know those arguments.

Fleischman: Yeah, I’ve heard them. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about where to draw the line. Brian Tomasik, who is involved with ACE, he has definitely muddied the waters for me in terms of how I think about consuming insects or farming insects.

Herzog: Yeah, I don’t see a downside to eating bugs; I’ve eaten insects before, I’ve eaten jellyfish, etc. and they weren’t that bad.

Fleischman: People have told me that jellyfish are on par with oysters and mussels, but I haven’t looked very deeply into that. Partly because I’ve never seen them in a restaurant, so I haven’t thought much about eating them.

Herzog: When I was writing that meat chapter, I included a list of things that I would not eat, and jellyfish was on that list. Then about a week later I was in a Chinese restaurant in Boston with my wife and jellyfish was on the menu. It was a big moral decision. Well, it wasn’t really a moral decision. It was just a question of “God, can I really eat jellyfish?” The answer, of course, was yes. But then after I ate the jellyfish, I had to go back and remove jellyfish from the list of animals in the chapter that I wouldn’t eat and shift it to the list of animals that I would eat.

Filed Under: Interviews & Conversations Tagged With: leafleting, messaging, psychology

About Allison Smith

Allison studied mathematics at Carleton College and Northwestern University before joining ACE to help build its research program in their role as Director of Research from 2015–2018. Most recently, Allison joined ACE's Board of Directors, and is currently training to become a physical therapist assistant.