Crossroads Series: What lessons can animal advocates learn from other social movements for change?

Introduction

Social movements are responsible for some of the most powerful changes around the world. From gender and racial equity to voter and LGBTQ+ rights, social movements have the ability to change policies, introduce new laws, and, most importantly, change the mindset of millions of people.

Movements start when a group of people work together toward a common goal, whether that be social, cultural, or political, and continue to build a sustained campaign for long-term change for an issue. The focus is usually on some form of injustice or opportunity for change. Regardless, there’s one thing that all social movements need to be successful in their mission: public support.

Learning from people in other, more established social movements can be invaluable due to their wealth of knowledge; drawing on their successes and failures presents insights into how advocates can be more effective in their efforts. Additionally, human and non-human animal movements have overlapping objectives and can strengthen each other. While the farmed animal advocacy movement is still relatively new, what lessons can animal advocates learn from other social movements for change?

Thank you to Christopher Eubanks for helping to answer this critical question.

This is part one of Crossroads, a blog series about what human-focused social movements can teach us about nonhuman animal advocacy.

Note: this contribution has been edited for length and clarity.

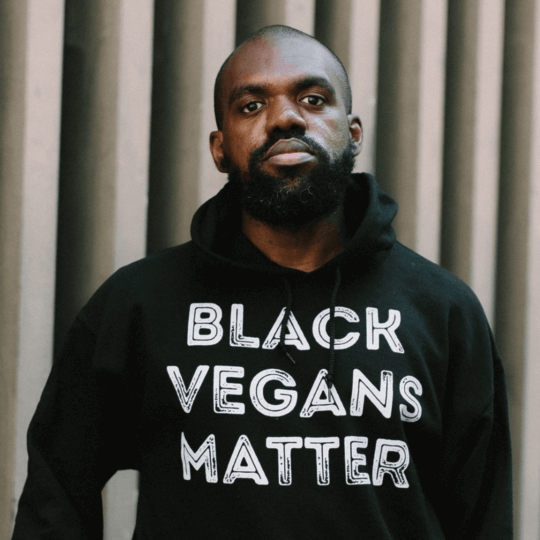

Christopher Eubanks

Founder, APEX Advocacy

Christopher “Soul” Eubanks (he/him) is a social justice advocate, creative, and public speaker raised in Atlanta, Georgia, dedicated to doing advocacy work that combats all forms of injustice. After learning about the horrors of animal exploitation, Christopher became vegan, began doing community organizing, and helped co-organize Atlanta’s first-ever animal rights march. He founded APEX Advocacy in 2021 with the intention of increasing the number of BIPOC individuals who participate in animal activism.

Can you tell us how your racial and animal justice work intersect and what this means for farmed animal advocacy?

One thing that made me connect these dots is that I grew up seeing footage of police violence against Black and brown people. In 1992, I saw the Rodney King footage at a very young age, and as the years continued, I would see more footage of Black men such as Philando Castile, Mike Brown, and George Floyd suffering at the hand of police violence. I reacted similarly to seeing slaughterhouse footage as I did to seeing Black men harmed and killed because I knew both were clearly blatant injustices. It made me understand that both of these forms of violence operate under systems of oppression and through a colonial, white supremacist framework. Once I saw those intersections, I personally decided that I had to say something and be a person that helps people understand how the oppression of animals is a social justice issue and connects to other social injustices. It was this early connection that led me to do animal advocacy.

I think we should tread carefully when comparing oppression; we should learn to “respect” other oppressions and not make comparisons. These intersections provide an opportunity for the farmed animal advocacy movement to learn how to be more mindful and considerate of how we use language in regard to comparing animal exploitation to other social justice movements.

What have you found to be the most effective interventions for opening peoples’ minds toward injustice?

When we speak about animal advocacy, people can initially get quite defensive as they feel you’re making them choose between things they care about. But it’s not necessarily because we’re saying it in an aggressive manner, it’s just that our current society hasn’t given much space to animal rights. Try not to convince people to care about animals or go vegan. Instead, find the common ground that we have morally and show them that their compassion for other social justices actually applies to the injustice toward animals. Breaking down these defenses has been very impactful and successful in my interactions.

Another important thing is to listen rather than just trying to prove a point. I make sure to listen to people and not have preconceived notions. For example, when speaking to a non-vegan, we must remove these labels and connect with people on a human level. When we can connect with people personally, we can achieve a lot more for animals.

What is your advice to charities looking to make their programs more accessible to Black people, Indigenous people, and people of the global majority?

Having an actual connection to the people you’re trying to reach is invaluable. I sometimes think about how some of the bigger, more-established organizations have different versions of their organizations around the world. Instead of naming a specific region of the world after their existing organization, maybe we should take a more supporting and backseat role and let that region have its own organization. For instance, we may develop solutions that aren’t actually solutions for that region. Local people know more about what needs doing, where money should go, and how to connect with their communities, so we should let them take the lead.

“While it’s not feasible to have representatives in every country in each region of the world, it’s important to favor having stronger connections over more connections.”

With APEX Advocacy, we’re very intentional about where we want to be to get more people of color involved in animal advocacy. We make a conscious effort to go to the places where the people we’re trying to connect and build more genuine relationships with are. While it’s not feasible to have representatives in every country in each region of the world, it’s important to favor having stronger connections over more connections. Maybe you want to open up plant-based cafes all over the world. First, you should focus on a specific region, establish strong roots and relationships, and implement and execute your ideas before moving to another [area].

How do you think animal advocates can best show up for other social movements?

The best way to show up relates to what I said previously; having solid relationships with the people you want to connect with. Also, learning and seeking advice from the people in other social justice movements because they have a wealth of knowledge that the current animal rights movement doesn’t. So, establishing genuine relationships, showing up for others, and being willing to learn.

Why do you think solidarity will make the animal advocacy movement stronger?

It’s more important to have a stronger movement than a bigger movement. One thing that organizations can do is be anti-oppression across the board and be consistent in their anti-oppression. Unfortunately, there are claims of racism, sexual assault, and other injustices in the movement. When an [organization’s] stance is undefined in these areas, or they haven’t spoken out against these issues, it makes space for people to attack the movement’s stance in these areas, making the movement vulnerable. But if we’re consistent in our stances against oppression (e.g., not tolerating sexism, racism, ageism, etc.), this will create a more solid and effective movement.

About Holly Baines

Holly joined ACE in September 2021. She holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology—focused on human food choices—as well as a master’s degree in wild animal biology. Before joining ACE, she spent four years working in wildlife conservation. Holly is passionate about using communications to promote ACE’s mission and help as many animals as possible.

ACE is dedicated to creating a world where all animals can thrive, regardless of their species. We take the guesswork out of supporting animal advocacy by directing funds toward the most impactful charities and programs, based on evidence and research.

Join our newsletter

Table of Contents