The Albert Schweitzer Foundation

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2018 |

| Current Version | November, 2021 |

Archived Version: November, 2018

What does Albert Schweitzer Foundation do?

Albert Schweitzer Foundation (ASF) does not make grants like a typical foundation, but rather works as a nonprofit. They conduct corporate outreach campaigns encouraging companies to adopt cage-free policies and to make broiler and fish welfare commitments as well as commitments to provide additional and improved vegan options. They run a variety of veg outreach campaigns, including their newsletter “Vegan Taste Week,” as well as actions by local groups of volunteers. Additionally, their scientific division researches topics related to animal welfare and ways to improve the quality of their work.

What are their strengths?

ASF understands the value of setting goals to ensure that they consistently achieve quality results. They measure the impact of their work and actively look for ways to improve their materials and strategy. Through their work with corporations, they help create changes with key influencers that can ultimately affect large numbers of animals. They have developed a system for evaluating the success of their corporate work by considering both the number and impact of their corporate victories. ASF collaborates with many other organizations and is willing to share information and partner to achieve greater goals.

What are their weaknesses?

Though ASF has expanded their corporate outreach internationally and is expanding some of their programs to Poland, they primarily work in Germany. Their reach is relatively limited because the majority of their work impacts a single, relatively small country. Implementing a corporate policy in Germany would have about one quarter the impact of implementing a similar policy with a company with the same market share in the U.S., but we doubt it takes only one quarter the effort. Additionally, our culture survey and discussions with ASF staff indicated that ASF has a very hierarchical structure. While that may have some strategic advantages, some ASF staff feel that they lack sufficient autonomy to contribute meaningfully to ASF’s decision making.

Why did Albert Schweitzer Foundation receive our top recommendation?

ASF has a solid track record of corporate outreach in Germany, and we are optimistic that their strategy and skills will lead to meaningful progress in Poland, an area with a younger, smaller animal advocacy movement. Additionally, ASF is one of the first animal charities beginning to prioritize corporate outreach on behalf of farmed fish. We believe that fish advocacy is particularly high-impact due its large scale and its neglectedness. We are pleased to recommend donating to ASF.

How much money could they use?

We estimate that ASF has a total funding gap of approximately $460,000–$2.9 million, and that they could effectively put to use a total revenue of $4 million–$6.1 million.1, 2 We expect they would use additional funding to expand their legal and corporate outreach work in Germany and to grow internationally through their planned expansion.3 We also expect they would use additional funding to increase their staffing and increase their salaries to be more competitive with the private sector.

What do you get for your donation?

From an average $1,000 donation, ASF would spend about $530 on corporate outreach campaigns. They would spend about $270 on individual outreach, $160 on legal advocacy, and $40 on media outreach. Our rough estimate is that these activities combined would spare -110,000 to 220,000 animals from life in industrial agriculture.4

We don’t know exactly what ASF will do if they raise additional funds beyond what they’ve budgeted for this year, but we think additional marginal funds will be used similarly to existing funds.

Albert Schweitzer Foundation has been one of our Top Charities since November 2018. They were one of our Standout Charities from December 2014 to October 2018.

These estimates are based on ACE’s 2018 Room for More Funding Guesstimate model for Albert Schweitzer Foundation.

This range is a subjective confidence interval (SCI). An SCI is a range of values that communicates a subjective estimate of an unknown quantity at a particular confidence level (expressed as a percentage). We generally use 90% SCIs, which we construct such that we believe the unknown quantity is 90% likely to be within the given interval and equally likely to be above or below the given interval.

ASF is planning an international expansion, most likely to Switzerland and Hungary, although the final decision is yet to be made. This information was provided in a private communication with Mahi Klosterhalfen in 2018.

Sometimes our estimated cost-effectiveness ranges include negative numbers if we are not certain that an intervention has a positive effect, and it could have a negative effect—even if we think that isn’t likely. This doesn’t necessarily mean we think those interventions are equally likely to harm animals as to help them.

Table of Contents

- How Albert Schweitzer Foundation Performs on our Criteria

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Questions for Further Consideration

- Supplementary Materials

How Albert Schweitzer Foundation Performs on our Criteria

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Before investigating the particular implementation of a charity’s programs, we consider their overall approach to animal advocacy in terms of the cause(s) they advance and the types of outcomes they achieve. In particular, we consider whether they’ve chosen to pursue approaches that seem likely to produce significant positive change for animals—both in the near and long term.

Cause Area

ASF focuses on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we believe is a high-impact cause area. Within this area, it is worth noting that ASF has recently started some work aimed at improving fish welfare,1 which is a relatively more neglected subset of farmed animal advocacy.2

Types of Outcomes Achieved

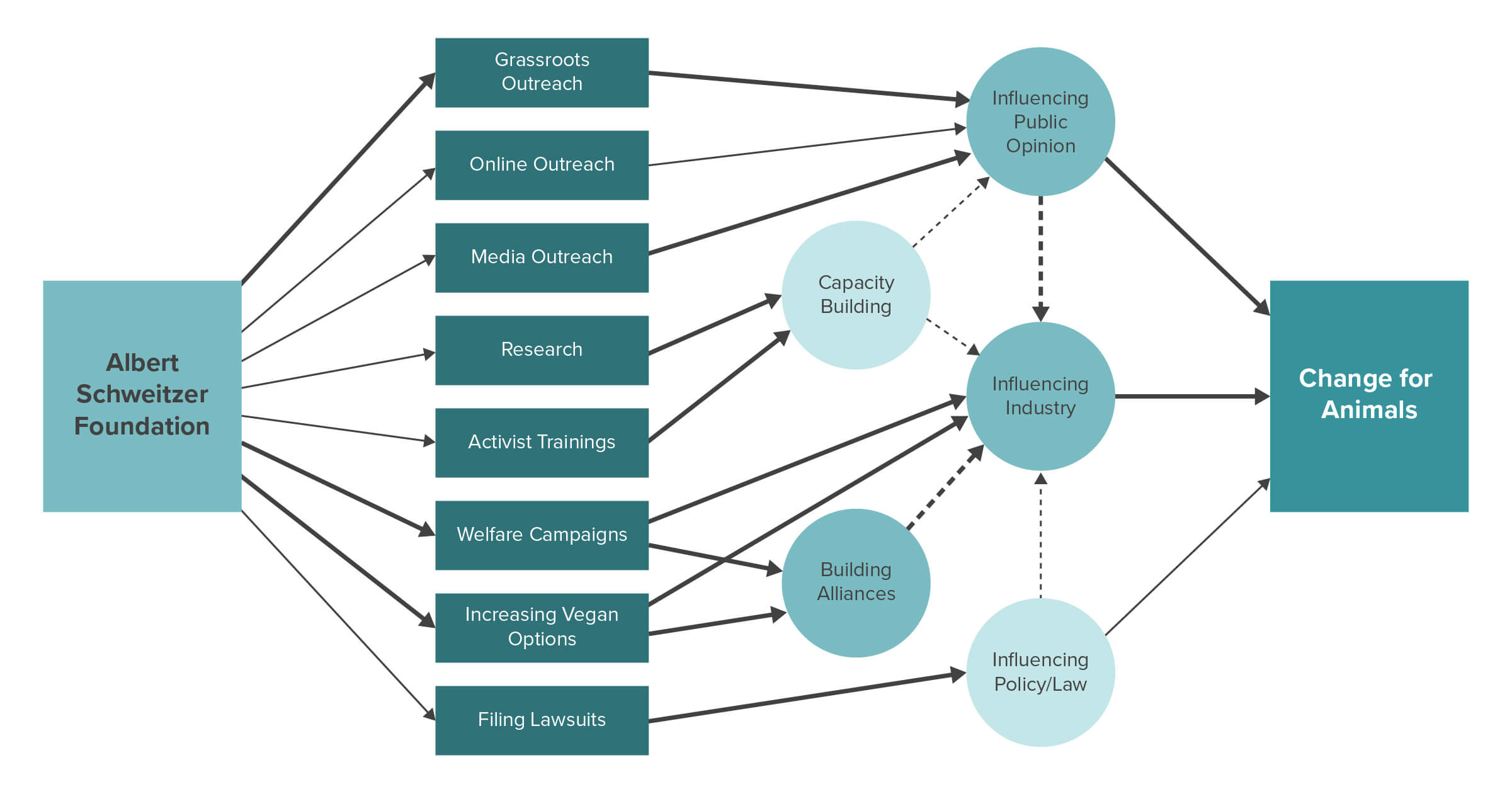

To better understand the potential impact of a charity’s programs, we’ve developed a menu of outcomes that describes five avenues for change: influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

ASF pursues many different avenues for creating change for animals: they work to influence public opinion, build the capacity of the movement, influence industry, build alliances, and influence policy and law. Pursuing multiple avenues for change allows a charity to better learn about which areas are more effective so that they will be in a better position to allocate more resources where they may be most impactful. However, we don’t think that charities that pursue multiple avenues for change are necessarily more impactful than charities that focus on one.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams.3 It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small and/or uncertain effects.

Influencing Public Opinion

ASF works to influence individuals to adopt more animal-friendly attitudes and behaviors through media outreach4 and virtual reality (VR),5 which we believe to be especially promising approaches.6 While it is difficult to measure incremental changes in public opinion—and, consequently, difficult to know when an intervention is more or less successful—we still think it’s important for the animal advocacy movement to target some outreach toward individuals. This is because a shift in public attitudes and consumer preferences could help drive industry changes and lead to greater support for more animal-friendly policies. However, we find that efforts to influence public opinion seem much less neglected than other categories of interventions in the United States.7 While we do not have direct evidence for the situation outside the U.S., we would expect it to be broadly similar to the U.S.

In addition to media outreach and VR, ASF also engages in several other forms of public outreach including Vegan Taste Week,8, 9 leafleting,10 and online outreach.11 ASF has recently expanded their consumer outreach beyond Germany into Poland with the launch of a Polish version of Vegan Taste Week. One strength of ASF’s approach to this work is that they utilize research and surveys to improve their implementation of these tactics and maximize impact.12 Another strength is that they are active in Poland, where there are far fewer organizations working in animal advocacy than in Germany.

Capacity Building

We see ASF’s efforts on animal advocacy research as an especially effective form of capacity building.13 Working to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement can have far-reaching impacts. While capacity-building projects may not always help animals directly, they can help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Our recent research on the way that resources are allocated between different animal advocacy interventions suggests that capacity building is currently relatively neglected compared to other outcomes, such as influencing public opinion and industry.

ASF publishes scientifically informed articles about animals, vegan health, and the relationship between animal agriculture and the environment.14 This work does not impact animals directly, but it may help other organizations, animal advocates, and the media to supply the public with more accurate information.

ASF also researches effective advocacy, which may play a pivotal role in how successful an organization can be. ASF is collaborating with other organizations to gather and make accessible information about available resources they think will be useful in the animal advocacy movement.15 Beyond providing information, ASF also helps advocates increase their impact by hiring regional coaches to help activist groups become more effective.16

ASF is also collaborating with a German university to create a bachelor’s degree program in vegan food management, which provides a relatively new potential avenue for recruiting activists into the animal advocacy movement.17 We have little evidence regarding the effects of such a program, largely because—to our knowledge—it’s the first of its kind. More research is needed in order to find out how the impact of this type of university program compares to other advocacy efforts, but it seems plausible that training leaders in the vegan food industry could strengthen that industry, which could in turn help more people consume fewer animal products. If graduates of the program are able to successfully produce and market alternatives to animal products, that might magnify the impact of grassroots outreach by making it easier for individuals to avoid buying animal products.

Influencing Industry

ASF works with corporations to adopt better animal welfare policies and to ban particularly cruel practices in the animal agriculture industry. Though the long-term effects of corporate outreach are yet to be seen, we believe that these interventions have a high potential to be impactful when implemented thoughtfully.18

Corporate outreach and change in the commercial sector form a significant part of ASF’s strategy; as they convince food companies to make changes to improve animal welfare and increase vegan offerings, ASF believes that the suppliers in the animal agriculture industry will be forced to follow.19 In doing this work, ASF has prioritized creating positive and cooperative relationships with companies and holding off on negative pressure until their more constructive efforts have proven fruitless.20 ASF pursues corporate outreach aimed at increasing plant-based offerings and meat reduction as well as outreach aimed at welfare improvements for land animals and for fish. They are planning to expand their budget for aquaculture outreach,21 which we see as a currently neglected,22 large-scale,23 and plausibly tractable24 area, so the marginal benefit of additional investment may be high.

ASF’s strategy is to try to build cooperative relationships with corporations through negotiations on welfare commitments, which they hope will make later (and potentially more challenging) efforts to displace animal-based products with plant-based products more successful.25 Aside from working directly with companies to secure welfare commitments, ASF also engages in creating and distributing vegan handbooks for caterers,26 publishing industry rankings based on vegan offerings,27 and publishing a website and newsletter with information and resources to help move the food industry away from using animals and towards a more plant-based focus.

The outcomes of some types of corporate outreach (such as cage-free commitments) are easier to quantify than others (such as handbooks for caterers or industry rankings of vegan friendliness). This makes comparisons of impact between these distinct approaches difficult. We think that overall, ASF’s strategy and approach to influencing industry is promising and likely to have a positive impact for animals.

Building Alliances

ASF’s outreach to key influencers provides an avenue for high-impact work, since it can involve convincing a few powerful people to make decisions that may influence the lives of millions of animals.28 Unless these key influencers are significantly more difficult to reach, this seems more efficient than general individual outreach because a great deal more individuals would need to be reached to create an equivalent amount of change.

A core part of ASF’s strategy is engaging with key influencers, who they refer to as “multipliers.”29 ASF engages with key influencers through targeted networking activities, maintaining a press distribution list, visiting specialist events, participating in working groups, giving presentations, and commissioning studies.30 In Poland, ASF has worked on building alliances with other movements—such as the Women’s Congress, within which they established the Animal Center, and the Equality Parade, where they added improved farmed animal welfare to the list of goals.31 Alliances such as these have the potential to help promote a more inclusive and diverse movement. Researchers have found that individuals from minority groups may feel ostracized from campaigns due to messaging and the perpetuation of normative conceptions of vegetarianism and veganism and/or veg individuals.32, 33, 34 Using social justice spaces to promote animal protection may have several benefits: novel audiences could be reached; strategies could be shared; and efforts could be made to address systems of human oppression.35, 36, 37

Influencing Policy and the Law

ASF works to encode animal welfare protections into law, which we think may be especially effective at creating change.38 We think that encoding protections for animals into the law is a key component in creating a society that is just and caring towards animals. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects to be particularly long-lasting.

While it will be years before the cases are decided, ASF has begun the process of filing lawsuits on behalf of animals in Germany. They have started with a lawsuit aimed at banning the use of gestation crates in pig farming39 and a lawsuit aimed at improving conditions on turkey farms.40 If successful, the former could improve welfare for the almost two million female pigs currently in Germany.41 ASF plans to pursue lawsuits aimed at improving the welfare of a variety of farmed animal species in a variety of states with the goal of getting rulings at the highest levels.42 ASF may be particularly well suited to pursue these cases because they have a board with strong legal expertise.43 We think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to have an impact on a large number of animals, and are more likely to be followed through on than similar corporate campaigns.

Long-Term Impact

Though there is significant uncertainty regarding the impact of interventions in the long term, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.44 The potential number of individuals affected by a charity increases over time due to both human and animal population growth, as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Predictions about the long-term impact of any intervention are always extremely uncertain, because the effects of an intervention vary with context and are interdependent with concurrent interventions—with neither of these interactions being constant over time.45 When estimating the long-term impact of a charity’s actions, we consider the context in which they occur and how they fit into the overall movement. Barring any strong evidence to the contrary, we think the long-term impact of most animal advocacy interventions will be net positive. Still, the comparative effects of one intervention versus another are not well understood.46 Because of the difficulties in forecasting long-term impact, we do not put significant weight on our predictions.

While ASF focuses much of their strategy and measures their progress based on short- and medium-term goals, they also note that long-term approaches with convincing theories of change play a smaller but still relevant role in their strategy.47 One example of long-term thinking factoring into their strategy is in the idea that cooperative as opposed to adversarial relationships with food corporations may in the long run lead to lasting partnerships and more future success.48 Their expressed strategy in working to gain welfare commitments from corporations considers not just potential near-term welfare improvements, but also the longer-term goal of indirectly increasing prices for animal products which may, over time, reduce sales and help to make plant-based products more price competitive.49 The actual long-term impact of welfare commitments remains to be seen since we don’t know how well corporations will comply or how much work enforcement will take.

We’re generally optimistic that obtaining corporate welfare commitments will lead to improvements in welfare in the long term,50 reduce consumption of animal products via price increases,51 and may raise awareness of the terrible welfare conditions on factory farms.52 However, some evidence suggests that welfare will not be significantly improved in cage-free systems and that in some ways the situation for hens may be worse, particularly in the transition from caged systems to cage-free systems.53, 54 ASF told us that this concern is why they are asking not just for cage-free commitments but also advocating for bans on beak trimming and for higher welfare standards in cage-free systems.55 Some animal advocates worry that marketing eggs and other animal products as “humane” may obscure the suffering and exploitation these purchases support. For some consumers, this may contribute to a belief that animals aren’t harmed in the production of “humane” products, which, some argue, could make subsequent efforts to reduce consumption of animal products more challenging.56, 57 ASF notes that when making announcements about these commitments they are careful to include information about how cage-free systems are worse than most consumers believe.58

ASF recently expanded to Poland and is preparing to expand to some relatively small countries such as Switzerland and Hungary.59 While the short-term impact in smaller countries may be smaller scale than in larger countries, it is plausible that laying the foundational groundwork for expanding to new countries—especially those with smaller animal advocacy movements—may have significant long-term impact.

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

In order to recommend a charity, we need to assess the extent to which they will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. Specifically, we need to consider whether there may be non-monetary “bottlenecks,” or barriers to the charity’s growth. First, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. Next, we evaluate the charity’s room for more funding by considering existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential new programs and areas for growth. It is important to determine whether any barriers limiting progress in these areas are solely monetary, or whether there are other inhibiting factors—such as time or talent shortages. Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for more funding sooner than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we have suggested. Our estimates are intended to indicate the point at which we would want to check in with a charity to ensure that they have used the funds they have received effectively and are still able to absorb additional funding.

Recent Financial History

After receiving a large grant from the Open Philanthropy Project (Open Phil) in 2017, ASF ended up raising more money than anticipated.60 Prior to this grant, they did not have any donations larger than €40,000 (about $45,636) per year and they traditionally relied primarily on a large amount of small-scale monthly donations—€10–€12 (about $11–$14) on average—for the majority of their funding.61 They now have other significant donors, but do not want to become too dependent on them and plan to continue having a large number of small donors form the core of their funding.62 This, combined with slower-than-desired growth, has led ASF to hold a larger amount in reserves than they would like.63 Two reported reasons for this slow growth are that some of their activities, including starting legal proceedings and hiring through a government volunteer program, come with delayed costs—and there was a bottleneck in terms of how much work management could process.64 To address the bottleneck, ASF created a new position and internally promoted a Chief Operating Officer (COO) to share some of the work that had formerly been the responsibility of the CEO. This reportedly added a stronger focus on quality and structure.65

The chart below shows ASF’s recent revenues, assets, and expenditures.66

Planned Future Expenses

ASF has plans for growth through international expansion.67 The experience gained from their expansion into Poland should make these future expansions more likely to be successful.

ASF reports potential for additional staffing expenses within Germany as well. They report that their administration has been overworked recently, so they would likely benefit from additional staff.68 They also currently have nine employees through a government volunteer program in which the government pays the employees’ salaries for 12 to 18 months. After this time, ASF decides whether or not to hire the volunteer.69 Overall in 2018 they plan to fundraise €2,000,000 (about $2,282,640) and spend close to the same amount. They report considering spending down their reserves, which they say are currently higher than they would like.70 Based on a comparison with other reviewed charities, we are not concerned about their reserves being too large; their ratio of assets to expenses is similar to or lower than that of many other charities.

Assessing Funding Priority of Future Expenses

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area will likely vary in its potential cost effectiveness. In addition to evaluating a charity’s planned future expenses, we consider the potential impact and relative cost effectiveness of filling different funding gaps. This helps us evaluate whether the marginal cost effectiveness of donating to a charity would differ from the charity’s average cost effectiveness from the past year. We break down the total room for more funding into three priority levels, as follows:

High Priority Funding Gaps

Our highest priority is funding activities or programs that we think are likely to create longer-term impact in a cost-effective way, as well as programs which we have relatively strong reasons to believe will have a highly positive short- or medium-term direct impact in a cost-effective way.71

As described in Criterion 1, ASF has a number of programs that we consider promising, including media outreach, VR, research, corporate welfare campaigns, meat reduction work, outreach to key influencers, building alliances with other social justice movements, and legal work. Of these programs, we estimate they could effectively use the largest increases in funding for legal work.72 We also think they have significant room for funding for their planned expansions to Switzerland and Hungary.73 In terms of staffing, as already noted, senior staff has reportedly been stretched thin; we estimate they have some additional room for funding to hire additional senior level staff, as well as for their planned salary increases.74 If ASF is able to increase their salaries, this may help them to compete with the for-profit sector to attract and retain the most highly skilled staff.75 We estimate that ASF has a high priority funding gap of $1.1 million–$2.8 million for 2019.76, 77, 78

Moderate Priority Funding Gaps

It is of moderate priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively moderate marginal cost effectiveness.

As described in Criterion 1, ASF has a number of other programs including Vegan Taste Week, online outreach, handbooks for caterers, and industry rankings. Of these, we think they have the most room for funding to expand Vegan Taste Week since they plan to expand to two new countries—presumably Switzerland and Hungary. Their budget for Vegan Taste Week saw an approximately 30% increase from 2016 to 2017 when they added Veggie Taste Week in Poland.79 We estimate that ASF has a moderate priority funding gap of $230,000–$1.3 million for 2019.80

Low Priority Funding Gaps

It is of low priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively lower marginal cost effectiveness, or to replenish cash reserves. Because it is likely that there may be future expenditures we haven’t thought of, we also include in this category an estimate of possible additional expenditures (based on a percentage of the charity’s current yearly budget).

Using a range estimate of 1%–20% of their projected 2018 expenses to account for possible additional expenditures, we estimate that ASF has a low priority funding gap of $20,000–$560,000 for 2019.81

The chart below shows the distribution of ASF’s gaps in funding among the three priorities: 82

With their plans for international expansion—on top of the already large amount of domestic projects ASF is engaged in—we believe they have significant room for more funding. We estimate that next year they have a total funding gap of approximately $460,000–$2.9 million,83 and that they could effectively put to use a total revenue of $4 million–$6.1 million.84

Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

ASF runs several programs; we estimate cost effectiveness separately for a number of these programs, and then combine our estimates to give a composite estimate of ASF’s overall cost effectiveness.85 We generally present our estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. We think that this quantitative perspective is a useful component of our overall evaluation because we find quantitative models of cost effectiveness to be:

- One of the best methods we know for identifying cost-effective interventions86

- Useful for making direct comparisons between different charities or different interventions87

- Useful for providing a foundation for more informative cost-effectiveness models in the future

- Helpful for increasing our transparency88

That said, the estimates of equivalent animals spared per dollar should not be taken as our overall opinion of the charity’s effectiveness. We do not account for some programs that have less quantifiable kinds of impact in this section, leaving them for our qualitative evaluation. For programs that we do include in our quantitative models, our cost-effectiveness estimates are highly uncertain approximations of some of their short-term costs and short- to medium-term benefits. As we have excluded more indirect or long-term impacts, we may underestimate the overall impact. There is a very limited amount of evidence pertaining to the effects of many common animal advocacy interventions, which means that in some cases we have mainly used our judgment to assign quantitative values to parameters.

We are concerned that readers may think we have a higher degree of confidence in this cost-effectiveness estimate than we actually do. To be clear, this is a very tentative cost-effectiveness estimate. It plays only a limited role in our overall evaluation of which charities and interventions are most effective.89

Corporate Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 ASF will spend about 53% of their budget, or $917,000, on corporate outreach.90 This results in some companies adopting new policies, and these policies likely result in reduced suffering for animals. We estimate that ASF’s corporate campaigns will help cause 47–79 policy changes, affecting 80–320 million laying hens and broiler chickens each year.

Individual Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 ASF will spend about 27% of their budget, or $468,000, on individual outreach.91 This will result in the addition 48,000–66,000 subscribers to their vegan taste week program, 600–800 viewers of VR footage, and 85,000–110,000 pieces of literature being distributed.

Legal Advocacy

We estimate that in 2018 ASF will spend about 16% of their budget, or $277,000, on legal advocacy.92

Media Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 ASF will spend about 4% of their budget, or $71,000, on media outreach.93 This will include the recruitment of 150–200 potential volunteers and the launch of 2–5 petitions.

Budget Changes Since 2017

The following chart shows the ways in which ASF’s budget size and allocation has changed since 2017.

All Activities Combined

To combine these estimates into one overall cost-effectiveness estimate, we translate them into comparable units. This introduces several possible sources of error and imprecision. The resulting estimate should not be taken literally—it is a rough estimate, and not a precise calculation of cost effectiveness.94 However, it still provides some useful information about whether ASF’s efforts are comparable in cost effectiveness to other charities’.95

We use our leafleting cost-effectiveness estimate and some aggregated staff estimates to estimate that ASF spares between -1 and 0.3 animals from life on a farm per dollar spent on individual outreach.96, 97 Even though the range estimated for individual outreach extends further into negative values than positive values, we think that overall the impact of ASF’s individual outreach is more likely net positive for animals.98

We consider multiple factors99 to estimate that ASF spares an equivalent of between -200 and 450 animals per dollar spent on corporate outreach.100, 101

We exclude legal advocacy and international outreach results from our final cost-effectiveness estimates and don’t attempt to convert them into an equivalent animals spared figure; it is too difficult to disentangle the effects of these programs from the total effects of their other programs.

We weight our estimates by the proportion of funding ASF spends on each activity; overall, we estimate that in the short term—after excluding the effects of some of their programs—ASF spares between -110 and 220 farmed animals per dollar spent.102, 103 This equates to between -100 and 180 years of farmed animal life spared104 per dollar spent.105, 106, 107 Because of extreme uncertainty about even the strongest parts of our calculations, we feel that there is currently limited value in discussing these estimates further. Instead, we give weight to our other criteria.

Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

To evaluate a charity’s track record, we consider how well the charity has executed previous programs. We also consider the extent to which these previous programs caused positive changes for animals. Information about a charity’s track record helps us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments—information that cannot always be incorporated into the criteria above. An organization’s track record can be a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences in other important factors.

Have programs been well executed?

ASF reports that most large-scale companies operating in Germany have either pledged to stop or have stopped using cage eggs due in part to ASF’s work, sometimes in collaboration with other charities.108 ASF recently expanded to Poland, and has reported cage-free successes there too.109 Their corporate outreach work also seemed to play an important part in stopping beak trimming of layer hens.110, 111 Since mid-2017 ASF reports they have been working intensively on improving broiler welfare, through their help in formulating the E.U. Broiler Ask112 and by contributing to Nestlé’s commitment to the new standards.113 Although their corporate outreach for broilers is a recent development, Nestlé’s commitment points to the program being well executed. Since at least early 2017, ASF is also expanding into corporate campaigns to improve the welfare of farmed fish, reportedly working with some major German supermarkets to develop welfare policies.114 ASF is still in the process of researching and developing an ask, so there is only quite limited information about how well ASF’s work focusing on farmed fish has been executed.

Another of ASF’s major programs is their industry rankings program. For the past few years, ASF has ranked German supermarket chains according to the availability of their vegan options.115 This project led to conversations with those chains seeking to improve their rankings, with some chains eventually improving their vegan selections.116 In 2017 ASF updated their ratings of the vegan-friendliness of food retailers.117 While the amount of vegan options at retailers is increasing, it is unclear to what extent this can be attributed to ASF’s benchmark surveys. In 2017, ASF also conducted an analysis of animal welfare standards in the food retailing industry, comparing chains based on 34 separate categories.118 Some chains have reported updating their policies in order to improve in their rankings.119

ASF provides consumer information in the form of their “Even if you like meat…” leaflet, promotion of their Vegan Taste Week campaign, and through traditional and social media channels. In 2017, they report receiving 79,000 new Vegan Taste Week subscribers, distributing 250,000 leaflets, and reaching tens of millions of people through their media reports.120 ASF’s legal work is now supporting three lawsuits which would impact all farmed animals of a particular species in Germany—for example, one lawsuit is aiming to stop the use of farrowing crates for pigs and another is aiming to change the standards in turkey fattening farms. Additionally, their campaign against Christina Schulze Föcking, Minister for Environment, Agriculture, Conservation and Consumer Protection of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, reportedly garnered public interest and made it possible for a lawsuit to be filed against the minister, who has since resigned.121 ASF is also creating and distributing a vegan handbook to caterers.122 The guide is 180 pages long and seems relatively comprehensive: it includes recommendations and over 80 recipes designed for dining halls. According to ASF, hundreds of people who work in the food industry have requested the guide.123

ASF has also contributed to research on farmed animal welfare. For example, in 2016 they documented research regarding the debeaking of laying hens.124 They’ve also published information about the treatment of farmed animals and standard practices in animal agriculture. Their research has been referenced by politicians, authors, and other organizations.125 In 2017 they externally commissioned a study comparing the nutritional value of meat with conventional and organic alternatives.126

Have programs led to change for animals?

ASF’s corporate outreach programs seem to have led to demonstrable changes for animals. Most notably, they may have helped determine the way the German egg industry responded to the European ban of non-enriched battery cages. They campaigned for the industry to transition to a mainly cage-free model instead of using enriched battery cages, and it appears that the industry has mostly completed that shift.127 In contrast, there haven’t yet been fulfillments of the broiler or farmed fish commitments. The commitments made due to ASF’s corporate outreach campaigns will likely affect a large number of animals if they are implemented. As these commitments are not legally binding, it will be especially important to follow up with companies to ensure the commitments are adhered to by the deadlines.

It is possible that the media attention that ASF has earned might have had some direct and indirect benefits for animals.128 There is weak evidence that media coverage of the treatment of farmed animals is negatively correlated with meat consumption in the United States;129 if such a correlation exists, it is possible that such coverage nudges people towards reduction in meat consumption. If the correlation between media coverage and meat reduction also exists in Europe —and we expect it does—then ASF’s media coverage may help animals on a large scale by reducing demand for meat and other animal products.

Many of ASF’s programs attempt to influence individual behavior. The impact of such programs, like their discontinued mobile advertisement tour or their leafleting efforts, is difficult to measure. Our 2017 Leafleting Report indicated that leaflets seem relatively ineffective; we estimated that they produce a near-zero expected change in years of farmed animal lives averted per dollar. Therefore, the hundreds of thousands of leaflets that ASF handed out could have quite limited impact on animals. However, such outreach could have helped bring about institutional change and could have been an important part of building the farmed animal advocacy movement to what it is today.

Ranking food retailers based on vegan-friendliness may cause them to incorporate more plant-based options. This could potentially decrease recidivism by making avoidance of animal products a more convenient choice, ultimately leading to a decline in the number of animals used and killed for food.

ASF’s research may improve the effectiveness of their other programs, eventually leading to indirect change for animals. The impact of their catering handbooks is also indirect, and we are somewhat uncertain about their effectiveness. ASF has not yet made considerable progress through their legal campaigns, so at this time they have not led to significant change.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

A charity that has systems in place for assessing their programs is better equipped to move towards their goals effectively. By conducting self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs, and modify or end those that are less successful. When such systems of improvement work well, many stakeholders benefit: benefactors are inclined to be more trusting and more generous, leadership is able to refine their strategy for achieving their goals, and nonhuman animals benefit more.

To evaluate how well the charity adapts to successes and failures, we consider: (i) how the charity has assessed their past programs and (ii) the extent to which the charity updates their programs in light of those assessments.

Does the charity actively assess areas of success and failure?

We think that ASF is quite good at assessing areas for improvement in their work. They set relevant and measurable goals in almost every area, including finance, outreach, and media.130 ASF tells us that, in general, they reach the majority of the goals they set at the beginning of the year.131, 132 They also said they may be spreading themselves thin with too many simultaneous projects,133 so they are now cautious to set achievable goals. They reportedly continue to set goals that are fairly measurable and time-bound, and highly relevant to their greater goal.134, 135 However, they do not exclusively engage in programs that fit into their measurable goals. For example, they report that some work they do on industry rankings could be influential; that’s because companies requesting ASF’s help with expanding their vegan options seem to be at least partly motivated by these industry ranking publications.136 Still, ASF reported that since these programs are hard to measure, they do not count them as part of their direct goals.137 We believe that ASF continues to demonstrate their capacity to thoughtfully measure both programmatic impact and organizational effectiveness.138 Their corporate outreach programs are a good example. Because they recognize the complexity of measuring their success in that domain, ASF uses a system of “impact points” informed by the extent to which a company is influential, offers vegan alternatives, and sells their products.139

ASF seems particularly committed to evaluating their work to increase their effectiveness.140 As mentioned in Criterion 2, a strength of ASF’s approach is that they use research and surveys to improve the implementation of their goals and to maximize impact.141 For example, they assessed the outcome of their Vegan Taste Week program on the basis of the opening and click rate of their newsletter emails—key performance indicators they reportedly plan to use to improve their program.142 They have also reportedly been consulting their evaluation team for advice on how to improve documentation of their corporate outreach projects’ goals.143 Although they had alluded to this as early as 2016,144 they have reportedly now begun instituting measures to optimize organizational effectiveness, particularly improved project planning and communication.145

Does the charity respond appropriately to areas of success and failure?

ASF reports that whenever their programs are less successful than expected, they assess potential drawbacks to try to optimize their programs in the future. For example, they reported that the impact of their efforts to stop debeaking or beak trimming were not as effective as they could have been. Accordingly, they reported an actionable idea on how to improve their debeaking efforts in 2018—that is, to derive a clear list of demands based on research findings to generate enough pressure to put improvements into practice.146

ASF has also demonstrated that they actively correct and learn from their mistakes. When they expanded their corporate outreach work to Poland, ASF realized that there was some overlap between their work and that of Otwarte Klatki (Open Cages). They reported having made mistakes in this regard, and now coordinate more with Otwarte Klatki; they expressed a wish to prevent making the same mistake in the future and said they would attempt to avoid overlap from happening when expanding to other countries.147

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

A charity is most likely to be effective if it has a well-developed strategic vision and strong leadership who can implement that vision. Given ACE’s commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we generally look for charities whose direction and strategic vision are aligned with that goal. A well-developed strategic vision must be realistic to manage and execute. It is likely the result of well-run, formal strategic planning; when a charity’s leaders regularly engage in a reflective strategic planning process, revisions and improvements to the charity’s strategic vision are likely to follow.

Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-composed board?

Mahi Klosterhalfen has been the CEO of ASF since 2007. Our impression is that he engages thoughtfully with the animal advocacy and effective altruism communities, working to understand how he and ASF can be more effective. He also serves on Compassion in World Farming’s board of trustees, indicating a cooperative approach and the potential for him to learn from another established animal charity.

Klosterhalfen seems to take on a lot of responsibility within ASF. As both CEO and a member of the Board of Directors, he plays a central role in setting the organization’s strategy as well as the yearly goals for each department. Klosterhalfen and the rest of the board currently oversee ASF’s legal work department, and Klosterhalfen even ran ASF’s broiler campaigns in 2018.148 ASF seems to understand that Kolsterhalfen’s heavy workload is not sustainable; they recently hired a COO to take over some of his project management and operations tasks, and ASF’s corporate outreach team will take over the broiler campaigns in 2019.149 ASF’s senior staff are reportedly working to determine whether any more of Klosterhalfen’s responsibilities can be absorbed by other people.150 We think this is a good sign, and not just because it will make the CEO’s job more manageable. It could benefit the organization to involve more staff in processes like strategic planning, not least because it could give the staff a greater sense of ownership over their work.151

There are only three members of ASF’s Board of Directors, one of whom is Klosterhalfen. According to U.S. best practices, nonprofit boards should be comprised of at least five people who are independent from the organization’s staff.152 However, there is only weak evidence that following these best practices is correlated with success in the U.S., and if they are correlated, that may be because more competent organizations are more likely to both follow best practices and to succeed—rather than because following best practices leads to success. Klosterhalfen tells us that ASF has tried to expand their board, but that many of the people they considered were not aligned strongly enough with ASF’s strategy.153 We don’t have a clear sense of the challenges that may be associated with expanding a German-speaking board of individuals with the right qualifications, so maintaining their three-person board could be a reasonable choice for ASF.

ASF’s board includes a judge, a lawyer who was formerly a judge, and Klosterhalfen.154 While it is common for the CEO of an organization to also serve on the board, it can be concerning. The evidence for the importance of board diversity is somewhat stronger than the evidence recommending board sizes of five or greater, in large part because there is some literature indicating that team diversity generally improves performance.155 However, to our knowledge, the evidence of the impact of board diversity on organizational performance is less strong than the evidence of the impact of team diversity.156

Does the charity have a well-developed strategic vision?

Does the charity regularly engage in a strategic planning process?

Each year, ASF’s management team has a series of meetings in which they review their work from the previous year and discuss which projects they will continue or initiate the following year.157 During this process, the organization relies on their three-year strategy as a guide.158

ASF’s board plays an instrumental role in setting the organization’s three-year strategy. They do so with a focus on four “pillars” of change: companies, consumers, multipliers, and the law. They currently see working to influence companies and the law as more neglected, and thus a more promising approach in the short and medium term.

Does the charity have a realistic strategic vision that emphasizes effectively reducing suffering?

ASF’s mission is to “relieve as much suffering as possible,” and our impression is that they evaluate their own programs based primarily on the amount of suffering they relieve. We support ASF’s choice to focus on improving farmed animal welfare and promoting plant-based diets because we consider farmed animal protection to be the most promising area for doing the most good for animals, other things being equal. ASF’s framework for making progress in these areas also makes sense to us. Their “pillars of change” framework is quite similar to our own independently developed menu of outcomes.

Our impression is that ASF sets yearly goals that are both achievable and aligned with their long-term strategy. They shared a flow chart system with us, which they use to ensure that they launch projects only when (i) they have the staff capacity to complete the project, (ii) staff capacity is not needed to complete ongoing projects, and (iii) staff capacity could not be expended on a higher-priority project. Their sharp, consistent focus on project prioritization means that when they can’t achieve a longer-term goal right away, they have a clear sense of which steps to take and when.

Does the charity’s strategy support the growth of the animal advocacy movement as a whole?

ASF’s work seems to be playing an important role in supporting the broader farmed animal advocacy movement. By pushing for better animal policies in Germany, they set an example for other countries. Importantly, they directly leverage these policies to push forward international progress, campaigning for German companies to adopt better policies internationally. Their work in Poland could help give traction to advocacy work in Central and Eastern Europe.

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Effective charities are generally well-managed on an operational level; they should have healthy cultures and sustainable structures. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about their human resources policies and their perceptions of staff morale. We also speak confidentially with non-leadership staff or volunteers at each charity to solicit their perspectives on the charity’s management and culture.159 Finally, we send each charity a culture survey and request that they distribute it among their team on our behalf.160, 161

Does the charity have a healthy culture?

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly towards all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. One important part of acting responsibly towards stakeholders is protecting employees from instances of harassment and discrimination in the workplace. Charities that have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, since varied points of view improve a charity’s ability to respond to new situations.162 A healthy charity is transparent with donors, staff, and the general public and acts with integrity; in other words, their professed values align with their actions.

Our impression is that ASF’s culture is structured, efficient, and collaborative. ASF’s strong focus on strategy seems to pervade each department and all activities. According to our culture survey, ASF employees have a clear sense of what is expected of them and they generally have the support they need to meet their goals.

Many respondents to our culture survey described ASF as quite hierarchical. Yearly goals are mostly determined by ASF’s leadership and then communicated to the rest of the team. ASF’s staff seems fairly split in their opinions of this top-down approach. Some staff members told us that it makes the organization run more efficiently and that they still feel that leadership values their input. Other staff members told us that they would like to have a greater say in the organization’s strategy rather than simply being expected to execute the leadership’s vision.

Relatedly, more than one staff member reported fear of voicing their opinions at work. While each of them stated that their fear was “personal” and not a reflection of ASF’s culture, we wonder whether ASF could do more to make employee feedback feel welcome, or to provide alternative ways for employees to provide feedback if they are uncomfortable speaking up in meetings.

Does the charity communicate transparently and act with integrity?

ASF publishes regular reports that adhere to Germany’s Social Reporting Standard (SRS). The SRS is designed to promote transparency for nonprofits, much like financial reporting standards promote transparency for for-profit companies. The SRS emphasizes the reporting of each nonprofit’s outcomes and effectiveness.

Many respondents to our culture survey described transparency as one of ASF’s greatest strengths. ASF’s internal communication appears to be both transparent and efficient. The staff communicates in person as well as via email, an internal Facebook group, and an internal “wiki.” Several staff members told us that ASF’s meetings are consistently well-organized and effective.

Does the charity provide staff and volunteers with sufficient benefits and opportunities for development?

ASF provides ample opportunities for staff development, though it seems their staff is not always able to take advantage of those opportunities because they are busy with their regular work. Klosterhalfen tells us that ASF used to allow 20% of staff time for professional development, but they struggled to get staff to take advantage of this allowance. In light of this, they recently reduced the allowance to 5%–15% of staff time, and are now working on actively encouraging all employees to commit that time to professional development opportunities.163 ASF also provides employees with some funding for professional development: up to 500 euros per staff member annually, or more with approval from the COO.164

ASF employees tell us that they are generally satisfied with their compensation, benefits, and opportunities for development, though some staff reported a desire for more vacation time. Several staff members noted that there is sometimes a lack of practical, on-the-job training, but most agreed that support is always available when requested.

Does the charity have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion?

Like many animal charities, ASF struggles with cultivating a diverse team. Klosterhalfen tells us that the animal advocacy movements in Germany and Poland are not particularly racially diverse, and ASF’s team reflects that.165 ASF also has just two women in senior management positions,166 though they tell us they have been working on gender diversity in a few different ways, for example by using gender-neutral language in job postings.167

One sign that ASF has a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion is that they are willing to work with other social movements. Their Polish branch in particular is closely aligned with the feminist and LGBTQ+ movements. Klosterhalfen tells us that their staff members recently “brought the animal protection voice” to a women’s rights conference.168

ASF’s staff offered a few ideas that could make ASF more inclusive for certain communities. Some pointed out that by raising salaries, ASF could become a better option for working parents who need to support a family. Others pointed out that ASF could be more inclusive of people with disabilities by making its office more accessible and by making its job requirements more flexible.

Does the charity work to protect employees from harassment and discrimination in the workplace?

We are not aware of any instances of harassment or discrimination at ASF, though we recognize that there are numerous reasons why we might not be privy to such information if it does exist, and are therefore cautious not to take this lack of information as evidence that ASF is free of any issues with harassment or discrimination. Most respondents to our culture survey reported that they knew who to approach to discuss problems that arise at work. Many said they would be comfortable approaching their direct supervisor or the Managing Director.

ASF has not, to our knowledge, provided harassment or diversity trainings for staff. However, they are planning to arrange a training for the entire German team on sexual harassment and gender discrimination in November.169 They are also currently in the process of developing official harassment policies, which they are required to do in order to be eligible to receive grants from the Open Philanthropy Project and Tofurky.170 As indicated by our culture survey, ASF employees generally seem to feel that official harassment policies and trainings are not needed at ASF, either because ASF’s staff wouldn’t harass anyone or because ASF’s leadership would effectively handle any problems that arise. We take these responses as an indication that ASF probably should provide harassment trainings for their staff. As we’ve seen, harassment is pervasive; it comes in many forms and can happen anywhere.

Does the charity have a sustainable structure?

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in which current leadership might move on to other projects. The charity should seem unlikely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, they should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

Does the charity receive support from multiple and varied funding sources?

ASF has traditionally received most of their support from small monthly donations of ten to 12 euros, on average. Recently, they have begun to receive some larger donations—including a $1,000,000 grant for two years of general support from the Open Philanthropy Project in 2017. ASF is aware of the risk of becoming too dependent on a small number of large donations; they plan to continue soliciting a large number of small donations as the primary source of their funding.171

Does the charity seem likely to survive potential changes in leadership?

In our view, ASF has very strong leadership; Klosterhalfen takes a very large share of the responsibility for the organization’s success, and he may be difficult to replace if the occasion should ever arise. However, ASF is a fairly large organization with a talented and committed staff. They have well-documented policies and training materials. Their strategy documents would provide guidance through any leadership transitions; these documents are clear and are set for three years at a time. We think that ASF could likely survive a potential change in leadership.

Questions for Further Consideration

No matter how thoroughly we research a charity, there will always be open questions about some aspects of the charity’s strategy or programming. We’ve asked charities some of those questions, and we present their answers below, without commentary.

Some would argue that the development of new cultured and plant-based food technology will be the key turning point for ending animal farming, and that a shift in public attitudes will naturally follow. What role does ASF play in facilitating the development and acceptance of technologies?

ASF’s Response:

“While we do hope that the development of new cultured and plant-based food technology will be the key turning point for ending animal farming, and that a shift in public attitudes will naturally follow, we’re probably in the less optimistic half of effectiveness-minded groups. We fear that lawmakers, regulators, the media, and the public will be far less open to change than we’d like them to be. Nonetheless, we’re speaking out for plant-based meats all the time (to our email subscribers, lawmakers, food businesses, influencers) and we’re taking opportunities to speak out for cultured meat as well (same channels but at a lower frequency), all of which mostly covers acceptance. Regarding the development of plant-based alternatives, we’re quite active at matching companies (e.g., developers of egg-alternatives with producers of vegetarian/vegan products). I don’t think we play a very relevant role at helping with the development of cultured food.”

Given that the corporate pledges ASF campaigns for are non-binding, how can we be sure that they meaningfully support improvements in farmed animal welfare?

ASF’s Response:

“Since we mostly work with German companies, this hasn’t been an issue in the past at all. German companies usually do first and talk later (so most of our cage-free victories were only announced after the transition to 100% cage-free eggs or just a couple of months before that). The work we’ve been doing recently (broilers and fish) is different, as the higher-welfare alternatives are hardly available. However, we’ve yet to encounter a German company that pledges to do something and doesn’t follow through (the case that comes closest to an exception is that Metro Germany couldn’t switch their egg product to 100% cage-free because of the Fipronil crisis—so the switch got delayed). Also, we haven’t met a company that pledges first and checks feasibility later (which sometimes seems to happen in the U.S.). German companies usually won’t pledge before they’ve finished negotiations with their suppliers.

The story is somewhat different in Poland. Neither we nor anybody else has experience with how well companies follow through with their pledges. We’ll certainly monitor the developments in the egg industry and keep following up with the companies we’ve convinced to go cage-free. We’ll work with other groups doing so (we’re fans of CIWF’s EggTrack).”

How tractable is promoting concern for farmed animals in Poland? Do you find that different kinds of work are more or less effective there due to cultural or political differences?

ASF’s Response:

“The biggest difference we see in Poland is that companies need more pressure to commit. The main reason seems to be that the cage-egg industry was already in decline when we jumped on the topic in Germany. There is less awareness and less momentum in Poland (though the Polish groups recently arrived at 100 commitments combined). Fortunately, we don’t have to rely on promoting public concern for farmed animals in Poland, as we find general concern to be high enough for conducting corporate outreach. I think that’s true for the entire E.U.. We have a strong corporate outreach focus in Poland, so I can’t talk much about different kinds of work. Our first impression is that consumer outreach for increased plant-based eating isn’t easier than it is in Germany.”

;Revenue;Assets;Expenses; 2015;$932,393;$831,724;$844,029; 2016;$1,310,957;$846,886;$1,198,372; 2017;$1,835,704;$1,382,562;$1,629,449; 2018 (estimated);$2,312,036;$1,067,423;$2,312,036; 2019 (estimated);$3,332,625;$1,000,000;$3,332,625;

,Lower estimate,Upper estimate High Priority,1100000,1700000 Moderate Priority,230000,1070000 Low Priority,20000,540000

;2017;2018; Corporate Outreach;$625,052;$917,414.79; Individual Outreach;$495,703;$468,200.77; Legal Outreach;$45,349;$277,259.73; International Outreach;$254,893;$70,833;

“The first major accomplishment [of the past year] is ASF’s aquaculture work. Within a short period of time, we managed to get most relevant stakeholders on board, including producers, organizations, and scientists. Furthermore, some of the biggest supermarket chains in Germany committed to improving fish welfare. Although no lives have been affected yet, all the relevant structures were put in place to have an impact in the future.” —Conversation with Mahi Klosterhalfen of Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2018)

For more information, see ACE’s forthcoming report on farmed fish welfare.

See see pages 20–21 of Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Report on Effectiveness (2017) for their own Theory of Change diagram.

Media and online outreach is conducted with marginal utility in mind and not much time or money is dedicated. This information can be found in Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s 2018–2020 Strategy.

ASF has partnered with Animal Equality to use their iAnimal virtual reality presentation and reports having had 401 participants in the first half of 2018. This information can be found in Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Accomplishments (2018).

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

In our Allocation of Movement Resources report, we found that within the U.S. farmed animal movement, efforts to influence public opinion received more resources than any of the other avenues for change.

Vegan Taste Week in Germany and Poland is a website and newsletter program designed to help change attitudes and behaviors and they report that the success rate among active participants is high. This information can be found in Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s 2018–2020 Strategy.

They got 30,824 new subscribers to Vegan Taste Week in Germany and Poland in the first six months of 2018. This information can be found in Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Accomplishments (2018).

ASF reports having distributed 55,350 copies of the “Even If You Like Meat” brochure during the first half of 2018. This information can be found in Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Accomplishments (2018).

In terms of online outreach, ASF engages in regular email communications and runs a Facebook group that has nearly doubled in size in the first half of 2018 to a total of 25,477 followers. This information can be found in Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Accomplishments (2018).

“What sets us apart in this respect from many other organizations is that we utilize research findings and the findings obtained through our own evaluations (e.g., surveys) to improve our message in terms of both content and how it is communicated and to maximize the impact of our information work.” —Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Report on Effectiveness (2017)

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

ASF is working on a website to share key information about animal activism and what they have learned from experience. This information can be found in Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s 2018–2020 Strategy.

Through the Open Wing Alliance, ASF is gathering information on companies that produce egg replacer so that organizations wanting to pressure companies to leave out eggs can use this as a resource. This information can be found in our Conversation with Mahi Klosterhalfen of Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2018).

ASF gives regional coaches small work contracts to help increase the level of activity of activist groups. This information can be found in Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s 2018–2020 Strategy.

According to ASF’s website, their “involvement [in the creation of this program] stretches from introducing the idea to working out details, suggesting a professor and helping with accreditation to designing and teaching some courses.”

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

“When it comes to animal welfare issues, the animal industry—despite its lobbying strength—has no choice but to fulfill the requirements imposed by food companies.” —Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s 2018–2020 Strategy

In Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Report on Effectiveness (2017), ASF says that they first attempt to enter into constructive relationships with food companies before blacklisting them or launching campaigns against them because they have a goal of building cooperative relationships to address these problems in the long term.

Aquaculture is an area of work they have recently begun and it was listed as an area where ASF has room for more funding, according to Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Budget (2018).

“Our understanding is that farmed fish welfare is a relatively neglected topic by animal advocates, and corporate campaigns to improve farmed fish welfare are neglected by extension.” —ACE’s forthcoming report on improving farmed fish welfare

“Using the same methodology, our results, based on the 2015 FAO data, indicates there were between 52 billion and 167 billion (midpoint 109.5 billion) farmed fishes slaughtered that year.” —ACE’s forthcoming report on improving farmed fish welfare

While we currently have a limited understanding of the tractability of farmed fish welfare reforms, it is plausible that corporate campaigns for layer hen and broiler chicken welfare reforms may inform parallel efforts for fish. See ACE’s forthcoming report on improving farmed fish welfare for more information.

“By the end of 2017, the focus of our work with companies was more on animal welfare issues and less on plant-based projects. This will most likely remain the case through 2018. The idea behind this [is] that addressing animal welfare issues helps us build good relationships which we can then use to speak about plant-based options and meat reduction, which is a lot easier to do when we have warm corporate contacts.” —Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s 2018–2020 Strategy

In 2017 ASF created and distributed to more than 1,000 stakeholders a 180-page vegan guide for caterers that includes recipes and information about how to expand vegan offerings. By July 2018 ASF had distributed 362 more guides, with plans to distribute an additional 500 by the end of the year. This information can be found in our Conversation with Mahi Klosterhalfen of Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2018).

ASF published rankings of supermarket chains and the biggest German pizza chains according to their vegan friendliness. This information can be found in our Conversation with Mahi Klosterhalfen of Albert Schweitzer Foundation (2018).

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

ASF describes multipliers as “people and institutions from media (mainly journalists), politics (ministers, party spokespersons addressing animal welfare policy, and working groups), science (scientists, junior Researchers) and NGOs who are influential both within their fields and beyond.” —Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Report on Effectiveness (2017)

For more information see pages 35–39 of Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Report on Effectiveness (2017).

This information can be found on page 2 of Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Accomplishments (2018). See also ASF Poland’s page on their work organizing the Animal Center at the Women’s Congress, and Equality Parade’s page showing their list of demands.

For instance, Singer (2016) describes campaigns using stereotypical masculine notions to appeal to men. Associations with such campaigns and messaging may contribute to feelings that reduction is only for privileged individuals or that certain communities would not be welcome within the movement.

Singer, R. (2016). Neoliberal Backgrounding, the Meatless Monday Campaign, and the Rhetorical Intersections of Food, Nature, and Cultural Identity. Communication, Culture & Critique 10:344–364.See, for example:

– Broad, G.M. (2013). Vegans for Vick: Dogfighting, Intersectional Politics, and the Limits of Mainstream Discourse. International Journal of Communication 7:780–800.

– Harper, B.A. ed. (2010). Sistah Vegan: Black Female Vegans Speak on Food, Identity, Health, and Society. Herndon, VA.

– Ko, A. and Ko, S. (2017). Aphro-Ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters. New York, NY: Lantern Books.

– Wrenn, C. (2016). Fat vegan politics: A survey of fat vegan activists’ online experiences with social movement sizeism. Fat Studies 6:90–102.In addition, as human and nonhuman animal oppression are interlinked, forming coalitions can help address areas of intersection and increase effectiveness.

According to The Sistah Vegan Project: “Unless these organizations and businesses learn how to operationalize racial equity within their ethical veganism and/or animal rights goals, they will continue to produce uneven and segregated spaces (spatially and psychically) that negatively impact people of color and humanity’s potential for alleviating non-human animal suffering.”

According to an entry in Carol Adams’ blog: “So long as the movement fails to address the problem of sexual inequality, it is endangered by the dominant patriarchal culture, colluding in a regime of sexual hierarchy and domination that hurts women and gender nonconforming men—as well as non-human animals—and damages its own radically transformative potential. […] For feminists, animal activism’s failure to confront sexual inequality is tragic; but for animal activism, this failure may be fatal.”

For more information on this topic, see our blog post “How can we Integrate Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion into the Animal Advocacy Movement?”

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

“Half of this lawsuit is also funded by another foundation—Erna-Graff-Stiftung.” —Private communication with Mahi Klosterhalfen, 2018

“As of now, we are supporting a case that could bring an end to the use of gestation crates: We aim for a ruling which stipulates that the crates have to be wide enough for the sows to turn around. This would make gestation crates mostly useless to the pig industry.” / “Another lawsuit aims to put a stop to the horrendous conditions, which we consider contrary to animal welfare laws, on turkey fattening farms. This could benefit around 35 million turkeys every year.” —Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s page on Using Legal Leverage

“From a legal perspective, it is simply about ensuring that the 1.9 million female pigs in Germany have the space to lie down easily with outstretched limbs.” —Albert Schweitzer Foundation’s Report on Effectiveness (2017)