The Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP)

Archived Review| Review Published: | December, 2019 |

Archived Version: December, 2019

What does the Nonhuman Rights Project do?

The Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) is a U.S.-based organization working to achieve legal personhood and rights for some nonhuman animals. To this end, they are initially litigating—or planning to litigate—primarily on behalf of great apes, elephants, dolphins, and whales. Currently, the NhRP is only working on behalf of individual animals who belong to a species for whom there is ample, robust scientific evidence of self-awareness and autonomy. They view these qualities as sufficient, but not necessary, for recognition of common law personhood and fundamental rights. The NhRP is also pursuing legislative work to advance the legal rights of nonhuman animals: They have recently invested in developing a grassroots program to support their future legislative initiatives.

In addition to their legal and legislative work, the NhRP is also engaged in educational initiatives that aim to shift attitudes towards animals in society.

What are their strengths?

Attempting to achieve legal personhood for nonhuman animals could be a very promising avenue for reducing animal suffering in our society. The NhRP is the only organization in the U.S. that is directly pursuing litigation and legislation towards this end, and it’s likely that their work has substantially advanced the discussion about nonhuman animal rights in the U.S. We think that their upcoming grassroots campaigning initiative could play an important part in passing future animal-friendly legislation. Additionally, the NhRP’s cases have captured public attention, and their educational outreach is likely to have reached and influenced large audiences.

What are their weaknesses?

Currently, the NhRP is only working on behalf of individual animals who belong to a species for which there is ample, robust scientific evidence of self-awareness and autonomy. The NhRP believes it will be easiest to achieve legal rights for demonstrably autonomous nonhuman animals and that doing so is a necessary predicate for achieving legal rights for broader populations of animals.1 Although achieving legal personhood for a small number of animals would be a major achievement in itself, achieving legal personhood for a broader population of animals—such as those used in animal agriculture—would be much more impactful. We are highly uncertain about the extent to which achieving legal personhood for certain great apes and elephants might increase the chances of achieving legal personhood for broader populations of nonhuman animals. Extending their advocacy to farmed animals is not currently a part of the NhRP’s mission, and it seems unlikely that their approach would be tractable for larger groups of animals in the future.

The Nonhuman Rights Project was one of our Standout Charities from December 2015 to December 2019.

Table of Contents

- How the Nonhuman Rights Project Performs on our Criteria

- Interpreting our “Overall Assessments”

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Supplemental Materials

How the Nonhuman Rights Project Performs on our Criteria

Interpreting our “Overall Assessments”

We provide an overall assessment of each charity’s performance on each criterion. These assessments are expressed as two series of circles. The number of teal circles represents our assessment of a charity’s performance on a given criterion relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated.

| A single circle indicates that a charity’s performance is weak on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated: | |

| Two circles indicate that a charity’s performance is average on a given criterion, relative to other charities we’ve evaluated: | |

| Three circles indicate that a charity’s performance is strong on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated: |

The number of gray circles indicates the strength of the evidence supporting each performance assessment and, correspondingly, our confidence in each assessment:

| Low confidence: Very limited evidence is available pertaining to the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to other charities. The evidence that is available may be low quality or difficult to verify. | |

| Moderate confidence: There is evidence supporting our conclusion, and at least some of it is high quality and/or verified with third-party sources. | |

| High confidence: There is substantial high-quality evidence supporting the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to other charities. There may be randomized controlled trials supporting the effectiveness of the charity’s programs and/or multiple third-party sources confirming the charity’s accomplishments.1 |

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Overall Assessment:

When we begin our evaluation process, we consider whether each charity is working in high-impact cause areas and employing effective interventions that are likely to produce positive outcomes for animals. These outcomes tend to fall under at least one of the categories described in our Menu of Outcomes for Animal Advocacy. These categories are: influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

Cause Areas

The NhRP advocates for all nonhuman animals—particularly megafauna. We believe that some subdivisions of animal advocacy (for example, farmed animal advocacy) are more effective than others.

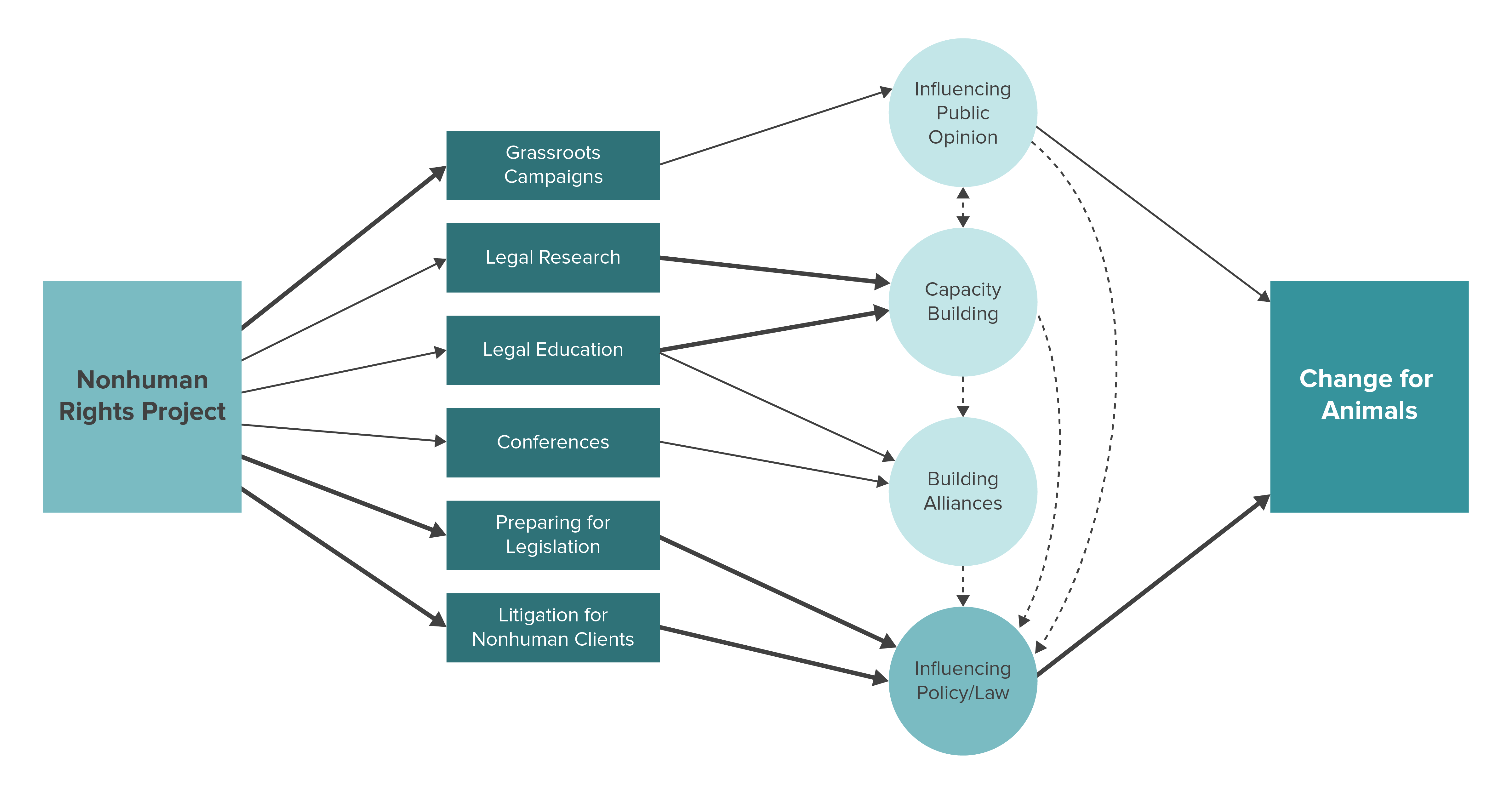

Theory of Change

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

A note about long-term impact

We do represent some of each charity’s long-term impact in our theory of change diagrams, though we are generally much less certain about the long-term impact of a charity or intervention than we are about more short-term impact. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew towards overemphasizing short-term impact. Nevertheless, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most. The potential number of individuals affected increases over time due to both human and animal population growth as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Interventions and Projected Outcomes

In addition to working to influence policy and law, the NhRP pursues several different avenues for creating change for animals: They work to influence public opinion, build the capacity of the movement, and build alliances. Below, we describe the work that they do in each area, listed roughly in order of the financial resources they devote to each area (from highest to lowest).

Influencing policy and the law

We think that encoding protections for animals into the law is a key component of creating a society that is just and caring towards animals. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects to be particularly long-lasting.

The NhRP uses a unique legal approach to helping animals. Their rights-based litigation seeks to provide long-term, stable protection for nonhuman animals under the law. By establishing animals as legal persons and providing a means for advocates to sue on an animal’s behalf, the NhRP seeks to establish legal protection first for some nonhuman animals, and perhaps later for many more. In keeping with this long-term focus, the NhRP’s current projects address only the first steps necessary for providing animals with justice through the legal system. Thus, there is room for considerable uncertainty about the eventual impact of their work.

In addition to their litigation approach, the NhRP is developing a legislative component of their strategy.2 We see legislation as a potentially high-impact way to help animals. It’s possible that achieving legal protections for animals might also influence public attitudes, either positively (e.g., by raising awareness of animal welfare) or negatively (e.g., by causing complacency or legitimizing the use of animals).

This year, the NhRP has invested in developing a grassroots program to support their future legislative initiatives. Grassroots campaigning has seemed to play an important part in successful animal-friendly legislation in the past, such as the Massachusetts Question 3 in 2016.

Influencing public opinion

The NhRP works to gain public support for animal rights. For instance, they were the subject of Pennebaker Hegedus Films and HBO’s 2016 documentary Unlocking the Cage. Since its release, the NhRP has worked with animal advocates to organize and promote screenings of the film. A survey of current vegetarians, vegans, and meat reducers indicates that books and documentaries are common self-reported catalysts for avoiding animal products, and we think that they could plausibly influence political opinion as well.

Despite the uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of most public outreach interventions, we think it’s important for the animal advocacy movement to target at least some outreach toward individuals. A shift in public attitudes and consumer preferences could help drive support for the NhRP’s future legislative initiatives. On the whole, however, we believe that efforts to influence public opinion are much less neglected than other types of interventions, as we describe in our report on the Allocation of Movement Resources.

Capacity building

Working to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement can have far-reaching impact. While capacity-building projects may not always help animals directly, they can help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Our recent research on the way that resources are allocated between different animal advocacy interventions suggests that capacity building is currently neglected relative to other outcomes, such as influencing public opinion and industry.

The NhRP conducts legal research that can build the capacity of the movement by educating the legal community on arguments for the legal rights of nonhuman animals. For instance, they wrote four law review articles that were published or accepted for publication in 2016 and 2017.3

The NhRP also builds the field of animal law by educating professionals and students of law. President Steven Wise has taught many legal courses over the years and recently finished teaching his annual summer course at Lewis & Clark Law School.4 We believe that educating law students on animal advocacy is a potentially high-impact intervention, since many may become lawyers, judges, or policymakers who have the power to make a difference for animals.

Building alliances

The NhRP’s outreach to key influencers provides an avenue for high-impact work since it can lead to convincing a few powerful people to make decisions that influence the lives of millions of animals. We believe that the impact of building alliances varies considerably depending on who the key influencers are and the kinds of decisions they can make.

The NhRP networks with key influencers by speaking at high-profile law schools and conferences. They also work with other attorneys to promote legal work for animals internationally.

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

Overall Assessment:

We look to recommend charities that are not just high impact, but also have room to grow. Since a recommendation from us can lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding, we look for evidence that the charity will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. We consider whether there are any non-monetary barriers to the charity’s growth, such as time or talent shortages. To do this, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. We also consider the charity’s existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential areas for growth and expansion.

Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. We check in with each of our Top Charities mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented below to indicate whether we still expect them to effectively absorb additional funding at that point.

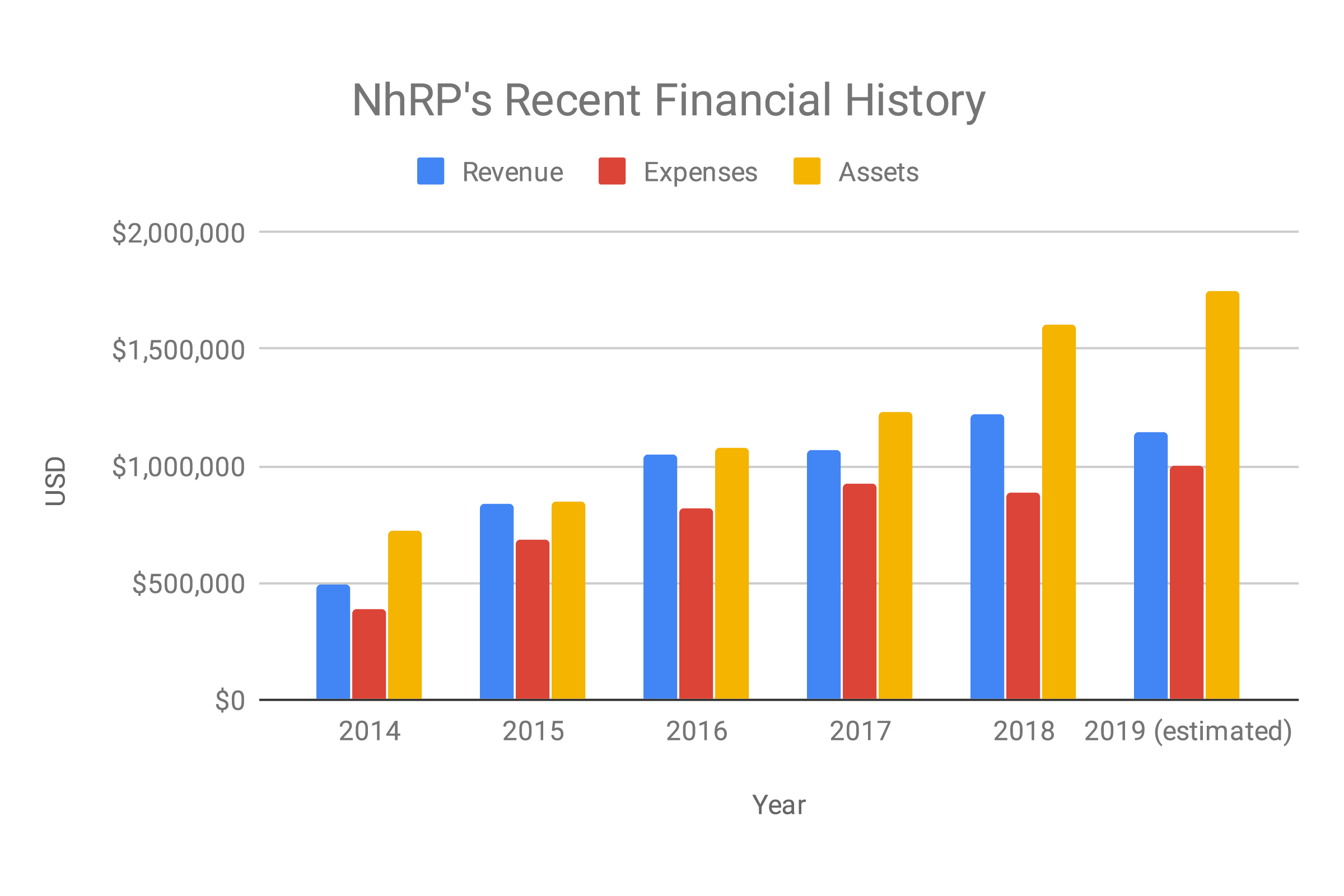

Recent Financial History

The following chart shows the NhRP’s recent revenue, assets,5 and expenses.6, 7 In this chart, the NhRP’s 2019 revenue and expenses are estimated based on their financials from the first six months of 2019.8 The NhRP expects no significant changes in the next year. They note they are on track to raise nearly $1.5 million in 2019.9 Note that this is not reflected in our model, as visualized in the chart.10

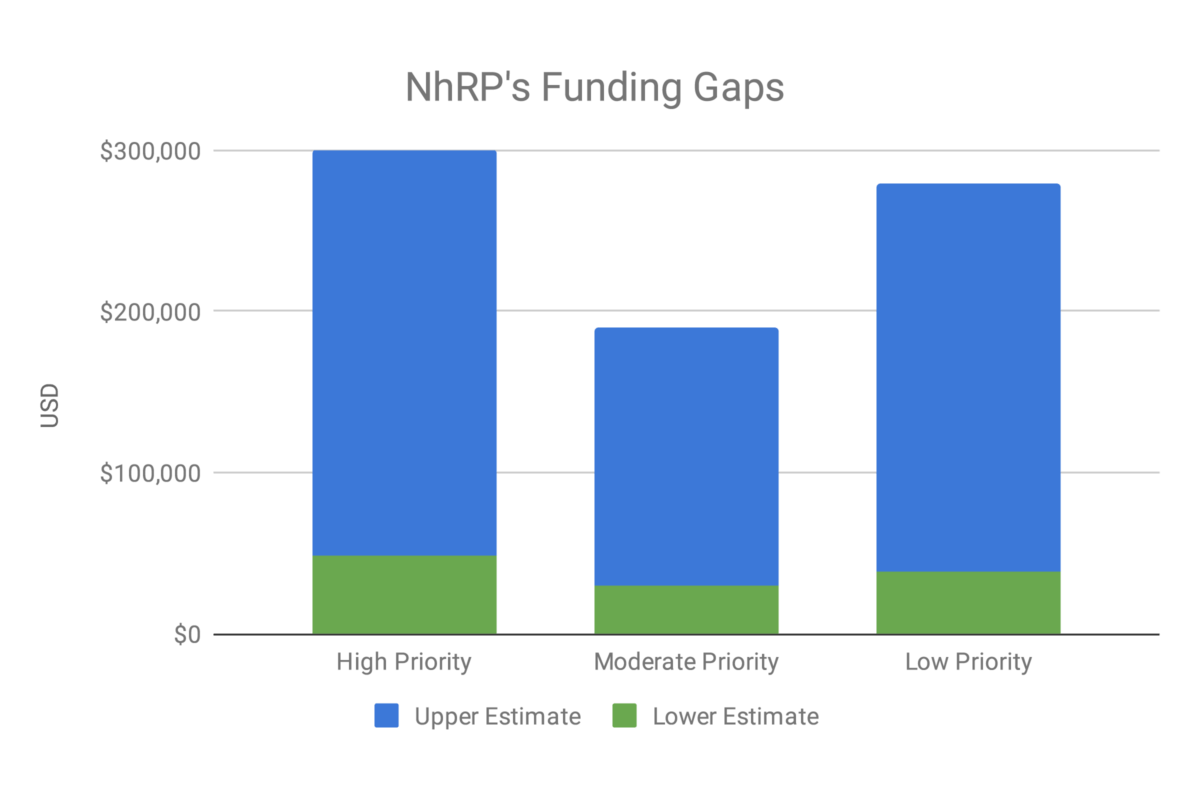

Estimated Future Expenses

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area likely varies in its cost-effectiveness. In order to evaluate room for more funding over three priority levels, we consider each charity’s estimated future expenses,11 our assessment of the effectiveness12 of each future expense, and the feasibility of meeting each expense if more funding were provided.13

| Estimated future expense | Funding estimate | Priority level |

| Hiring up to nine new staff members14 | $61k to $0.40M15 | High (37%) / moderate (63%) |

| Acquiring office space in New York and Los Angeles16 | $15k to $82k17 | Low |

| Expanding non-staff costs18 | $15k to $99k | High (37%) / moderate (63%) |

| Possible additional expenditures | $11k to $0.23M | Low |

Estimated Room for More Funding

The cost of the NhRP’s plans for expansion over the three priority levels is estimated via Guesstimate and visualized in the chart above. The costs of the expansion are expected to be between $0.16M and $0.64M. Our room for more funding estimates include a linear projection of the charity’s revenue from previous years to predict the amount by which we expect the revenue to increase or decrease in the next year. The NhRP has received funding influenced by ACE as a result of its prior Standout Charity status, so in order to more accurately estimate their room for more funding, we have subtracted the estimated ACE-influenced funding from our estimates of future revenue.19 Comparing the NhRP’s estimated revenue for 201920 and 2020,21 we predict that in the next year, it will change between -$0.17M and $0.42. As mentioned, we have not included ACE-influenced revenue in order to account for our own impact. In addition, we believe that the NhRP has particularly high reserves, and we believe they may be able to spend some of their reserves on their planned expenses. The estimates for change in revenue are more uncertain than the estimated costs of expansion, so we put limited weight on them in our analysis.

Criterion 3: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

Overall Assessment:

Information about a charity’s track record can help us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments, which is information that cannot always be incorporated into our other criteria. An organization’s track record is sometimes a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences between two charities.

In this section, we consider whether each charity’s programs have been well executed in the past by evaluating some of the key results that they have accomplished. Often, these outcomes are reported to us by the charities and we are not able to corroborate their reports.22 We do not expect charities to fabricate accomplishments, but we do think it’s important to be transparent about which outcomes are reported to us and which we have corroborated or identified independently. The following outcomes were reported to us unless indicated otherwise.

The Nonhuman Rights Project was founded in 2007 when they began their Education program. In 2013, they launched their Litigation program, and in 2016 they started their Legislation program. Below is our assessment of each of these programs, ordered according to the expenses invested in each one (from highest to lowest) in 2018–2019:

Program Duration

2013–present

Key Results23

- Received the first opinion of any U.S. high court judge on the merits of the NhRP’s legal arguments in favor of legal personhood and rights for nonhuman animals24 (2018)

- Secured the world’s first habeas corpus order on behalf of an elephant (who is currently confined at the Bronx Zoo)25 (2018)

- Submitted a taped statement to the Colombia Constitutional Court to encourage considering a habeas corpus petition for a bear (2019)

- Successfully lobbied the 2019 Black’s Law Dictionary to correct a decades-old error in its definition of a “legal person”26 (2019)

Our Assessment

Since late 2013, the NhRP has been litigating on behalf of animals. Until 2017, they were working on three cases involving four clients—all chimpanzees.27 Two of the clients were successfully transferred to the Project Chimps sanctuary in 2018 after years of the NhRP’s advocacy. Although the NhRP’s motions of appeal were denied for the other clients, a 2018 opinion by a U.S. court judge marks historic progress in securing fundamental legal rights for nonhuman animals.28

In 2017, the NhRP took on a new case involving three elephants, though it has not been successful so far.29 In 2018, they began a new case involving a fourth elephant30 and they secured the first writ of habeas corpus issued on behalf of an elephant.31

The NhRP supports lawyers in other countries who are working on similar cases, including the successful case of a chimpanzee in Argentina in 201632 and an ongoing case of a bear in Colombia.33

Since the NhRP’s Litigation program is both long-term and expansive, we are highly uncertain of its impact. However, it seems they have made progress in the legal battle for animal rights in the U.S and other countries. Thanks to their litigation work, historic habeas corpus orders on behalf of animals have been issued in the U.S. and their litigation model has likely influenced similar cases in other countries.

Additionally, the NhRP’s recent victory in influencing Black’s Law Dictionary to change the definition of a “legal person” could pave the way for future successes in the U.S.

Program Duration

2007–present

Key Results34

- Reportedly mentioned in about 1,500 news articles35 (2018–2019)

- Shared the results of a nationally representative survey they planned and conducted in partnership with Professor Garrett Broad of Fordham University (2018)

- Assisted Voiceless Australia with the creation of a teaching plan and curriculum for high school students on the subject of nonhuman rights36 (2018)

- Published seven law review articles, three book chapters, and other resources37 (2007–2017)

Our Assessment

The NhRP has successfully garnered media attention for their work. A 2016 documentary about them called Unlocking the Cage received many views and features in media outlets38 and is currently available to watch on HBO, Netflix, and Amazon Prime. In the past 12 months, they have continued to screen their documentary, though most of their media coverage now comes from their rallies and litigation work.39 Despite our uncertainty about the impact of media outreach, the NhRP’s work has likely increased public awareness of the legal status of animals, especially in the U.S.

Since its foundation, the NhRP has been working on capacity-building activities. Founder and President Steven Wise has been giving talks, teaching classes, and writing law review articles and books on legal rights for nonhuman animals for decades. Since 2018, he has given talks to support initiatives in Israel40 and the U.K41 aimed at securing legal rights for nonhuman animals in those countries. Although we are uncertain of the impact of this work, Wise’s expertise and advice has likely led other lawyers to improve the effectiveness of their work.

The NhRP’s assistance to Voiceless Australia in 2018 in creating humane education resources for high school teachers could reach many students in Australia and could be used as a model for other teaching plans and curricula. Creating resources for educators can impact a large number of students and might shift attitudes towards the status of animals in our society.

Program Duration

2016–present

Key Results42

- Strategically laid the groundwork for their municipal legislative initiatives (2018)

- Launched two campaigns for the release of their elephant clients, including three rallies and two petitions (2019)

Our Assessment

The NhRP began laying the groundwork for their Legislation program in late 2016. They ramped up their activities in early 2018 when they hired a Director of Government Relations and Campaigns. Since then, they have been preparing to launch municipal legislative initiatives in the U.S., with results yet to be seen. In 2019, the NhRP launched two campaigns for the release of their elephant clients, including three rallies and two petitions. One rally received large media coverage, prompting conversations with a local politician.43 Apart from the potential benefit for their clients in the short (or medium) term, these campaigns could impact more animals in indirect ways, for example by contributing to a shift in the way people think about animals’ status in society, or by paving the way for further legal victories for animals.

Despite the difficulty of assessing the indirect and long-term impact of the NhRP’s campaigns for animals, the media coverage and support they’ve achieved44 have likely strengthened their litigation work and influenced public opinion, advancing the discussion about the legal rights of nonhuman animals in the U.S.

Criterion 4: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

Overall Assessment:

A charity’s recent cost-effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component in understanding how cost-effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources and compare that to the outcomes they have achieved in each of their main programs.

This year, we used an approach in which we more qualitatively analyze a charity’s costs and outcomes. In particular, we have focused on the cost-effectiveness of the charity’s specific implementation of each of its programs in comparison to similar programs conducted by other charities we are reviewing this year. We have categorized the charity’s programs into different intervention types and compared the charity’s outcomes and expenditures from January 2018 to June 2019 to other charities under review. To facilitate comparisons, we have also compiled spreadsheets of all reviewed charities’ expenditures and outcomes by intervention type.45

Analyzing cost-effectiveness carries some risks by incentivizing behaviors that, on the whole, we do not think are valuable for the movement.46 Particular to the following analysis, we are somewhat concerned about our inclusion of staff time and volunteer time. Focusing on staff time as an indicator of cost-effectiveness can reward charities that underpay their staff, and discourage organizations from working towards increasing salaries to be more in line with the for-profit sector. As for volunteer time, we think that volunteer programs can increase the cost-effectiveness of a charity’s work, however, overreliance on volunteers can make a charity’s work less sustainable. While we think that these factors are relevant and worth including in our analysis of cost-effectiveness, we encourage readers to bear these concerns in mind while reading this criterion.

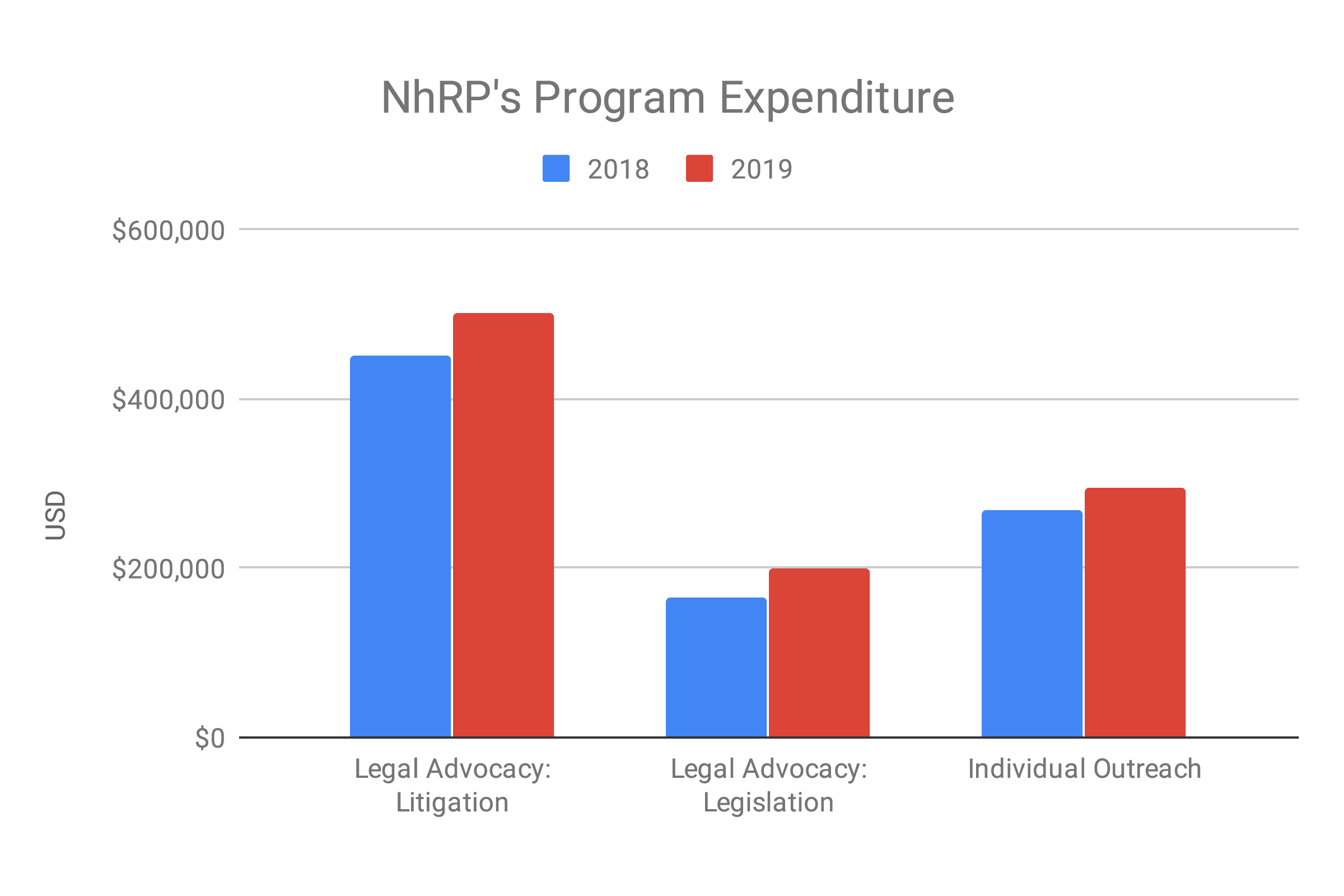

Overview of Expenditures

The following chart shows the NhRP’s total expenditures in 2018 and 2019, divided by program.47

We asked the NhRP to provide us with their expenditures for their top 3–5 programs as well as their total expenditures. The estimates provided in the graph were calculated by dividing up their total expenditures proportionately, according to the size of their programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost-effectiveness.

Legal Advocacy

Summary of outcomes: continued representation of their chimpanzee clients; secured “order to show cause” for their elephant client; successfully requested to amend an error in Black’s Law Dictionary; made progress on a grassroots campaign to free three circus elephants; and made progress on a grassroots campaign supporting their elephant client’s release (including a petition with more than 1 million signatures). For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in legal advocacy.

Use of resources

Table 1: Estimated resource usage in the NhRP’s legal advocacy, Jan ‘18–Jun ‘19

| Resources | The NhRP’s

Litigation |

The NhRP’s

Legislation |

Average across all reviewed charities48 |

| Expenditures49 (USD) | $700,000 | $270,000 | $500,000 |

| Staff time (weeks50) | 158 | 32 | 187 |

| Volunteer time (weeks51) | Unknown | Unknown | 12 |

Relative to their expenditures for this program, the NhRP’s staff time is slightly lower than the average of charities we reviewed this year. Note that the NhRP’s work differs substantially from the other charities we reviewed, so comparisons to the average should be given relatively less weight than for other charities.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

The NhRP’s legal advocacy has outcomes for animals that are indirect and likely to be realized on a much longer time scale than many of the other charities we review—this makes us a lot more uncertain in our assessment of their impact. Additionally, a portion of their work, such as their representation of some of their chimpanzee clients, has been ongoing for several years. As such, only considering their expenditures over an 18-month period means that our evaluation of their cost-effectiveness is an overestimate in some areas.

The NhRP’s work in the short term affects only the very small number of animal clients that they represent. Over the long term, it is possible that their impact may substantially increase if it becomes feasible that legal personhood could be granted to members of different species—particularly farmed animals. However, this is not currently a part of the NhRP’s mission, and their approach may not be tractable for farmed animals. Farmed animals are a much more integral part of society than the current clients that the NhRP represents, so it will be harder to secure changes for them without first changing society’s current perspective. However, if it is possible, it seems they would first need to successfully grant legal personhood to animals that are most closely related to humans, such as chimpanzees.

After accounting for all of their outcomes and expenditures, the NhRP’s legal advocacy seems less cost-effective than the average of other reviewed charities in 2019.

Media Campaigns

Summary of outcomes: received 1,500 media mentions with 1.23 billion impressions; expanded their presence on Instagram and Twitter; had work featured in a forthcoming graphic novel; made progress writing law review articles; conducted a survey assessing U.S. public support for the legal rights of nonhuman animals; assisted Voiceless Australia in producing a high school curriculum and teaching plan about non-human animal rights; presented two talks at law schools; and Unlocking the Cage (a documentary about the NhRP) received an Emmy nomination and was made available on digital media platforms. For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in media campaigns.

Use of resources

Table 2: Estimated resource usage in the NhRP’s media campaigns, Jan ‘18–Jun ‘19

| Resources | NhRP | Average across all reviewed charities52 |

| Expenditures53 (USD) | $420,000 | $640,000 |

| Staff time (weeks54) | 38 | 397 |

| Volunteer time (weeks55) | Unknown | 4 |

Relative to their expenditures for this program, the NhRP’s staff time is much lower than the average of charities we reviewed this year.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

The outcomes achieved by the NhRP’s media campaigns seem to generally increase public awareness of the work they do in their Litigation and Legislation programs. In some instances, they have used their media presence to more directly influence their work; for example, their use of Twitter seems to have helped generate public and celebrity support for their campaign to free Happy the elephant. However, it is not currently clear to what extent this public support has influenced the progress of their litigation cases. Generally, we think that using their media campaigns to directly influence their other programs is likely to make those media outcomes more cost effective, all else equal.

Compared to other charities we have reviewed in 2019, the NhRP seems to have achieved an average amount of outcomes. However, we are much more uncertain about the cost-effectiveness of those outcomes, due to the nature of their work.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

Overall Assessment:

By conducting reliable self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs and modify or discontinue less successful programs. When such systems of improvement work well, all stakeholders benefit: Leadership is able to refine their strategy, staff better understand the purpose of their work, and donors can be more confident in the impact of their donations.

In this section, we consider how the charity has assessed its programs in the past. We then examine the extent to which the charity has updated their programs in light of past assessments.

How does the charity identify areas of success and failure?

The NhRP doesn’t conduct formal self-assessments, but they have annual retreats where they review the effectiveness of their work.56 They tell us that they constantly revisit their strategic documents to ensure that they’re doing the most effective thing they can.57 After a major project, all NhRP departments, which work collaboratively, review their results in an organic process as often as needed.

In the past three years, the NhRP has consulted with various individuals and organizations to get support and advice on topics such as outreach, public relations, legal matters, content marketing, and website development.58

Although the NhRP finds it difficult to quantitatively estimate the outcomes of their programs, they measure certain aspects of their work including their media coverage, reach, and the number of law review articles that pertain to their work. They also analyze the development of the legal conversation around their work.59 In addition, since they began launching petitions, they have been using signatures to measure public engagement.

Does the charity respond appropriately to identified areas of success and failure?

We believe that the NhRP has recently responded appropriately to their self-determined areas of success and failure in at least the following way:

NhRP staff have been working with Professor Garrett Broad (Fordham University) on a research project (funded by ACE’s Animal Advocacy Research Fund) to determine what kind of strategic communication could work best to advance legal rights for nonhuman animals. Based on the project’s results, the NhRP decided to adapt their language to different audiences. They are not changing the language in their court filings, but they have decided to focus their messaging to the general public on the idea of “rights” rather than “personhood,” since the results of their study suggest that the term “personhood” may be misunderstood or alienating.60

We believe that the NhRP failed to respond appropriately to areas of success and failure in at least the following way:

In our previous reviews of the NhRP (2017, 2015), we noted concerns about the organization’s narrow focus on achieving legal rights only for individual animals who belong to certain species (species for which there is ample, robust scientific evidence of self-awareness and autonomy). The NhRP reports that they focus on these species because they believe they are the most likely “to be the first to break through the legal wall that separates all nonhuman animals from all human beings.”61 Based on this consideration, they continue to focus their work on animals belonging to these species, in particular chimpanzees and elephants, expecting their victories to open further opportunities to achieve legal rights for other animals. However, the NhRP has also reported that they have been supporting the legal case of a spectacled bear, a species that seems to be out of their scope.62 This decision suggests that they might be open to considering working on behalf of other animal species. It also might indicate that the NhRP should reconsider expanding the criteria they use to select their clients sooner than they had planned. We think the NhRP could significantly increase their impact by widening their scope and being more open to working with animals who may not be known to be as cognitively sophisticated as chimpanzees or elephants.

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

Overall Assessment:

Strongly-led charities are likely to be more successful at responding to internal and external challenges and at reaching their goals. In this section, we describe each charity’s key leadership and assess some of their strengths and weaknesses.

Part of a leader’s job is to develop and guide the strategic vision of the organization. Given our commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we look for charities whose strategy is aligned with that goal. We also believe that a well-developed strategic vision should include feasible goals. Since a well-developed strategic vision is likely the result of well-run strategic planning, we consider each charity’s planning process in this section.

Key Leadership

Leadership staff

The NhRP’s Founder and President is Steven Wise, who has served the organization for 23 years. Kevin Schneider is the organization’s Executive Director and has been for the past four years, after spending six years as a legal volunteer. Other members of leadership include Lauren Chopin, Communications Director, and Courtney Fern, Director of Government Relations. Asked to describe their leadership styles, many of the NhRP’s leaders describe themselves as “collegial” and/or interested in developing clarity and building consensus.

We distributed a culture survey63 to the NhRP’s small team64 and respondents agreed strongly that their leadership is attentive to the organization’s strategy. They also agreed strongly that the organization promotes internal transparency and they agreed (though slightly less strongly) that the organization promotes external transparency.

Board of Directors

The NhRP’s Board of Directors consists of four members, including Founder and President Steven Wise. It also includes Wise’s wife Gail Price-Wise, who has a background in diversity training and nonprofit consulting. The other two board members have backgrounds in law and wildlife protection. In the U.S., it’s considered a best practice for nonprofit boards to be comprised of at least five people who have little overlap with an organization’s staff or other related parties. However, there is only weak evidence that following this best practice is correlated with success.

As a relatively small board, the four members represent a limited range of occupations, backgrounds, and viewpoints. We consider the board’s small size and relative lack of diversity and independence to be a weakness. We believe that boards whose members represent occupational and viewpoint diversity are likely most useful to a charity since they can offer a wide range of perspectives and skills. There is some evidence suggesting that nonprofit board diversity is positively associated with better fundraising and social performance,65 better internal and external governance practices,66 as well as with the use of inclusive governance practices that allow the board to incorporate community perspectives into their strategic decision making.67

Strategic Vision and Planning

Strategic vision

NhRP’s mission is “to secure fundamental rights for nonhuman animals through litigation, legislation, and education.” This includes the achievement of animal rights worldwide, hence their attempts to collaborate with individuals and organizations outside of the U.S.68

We believe that achieving this goal could lead to immense benefits for animals, especially if it is achieved before industrial agriculture is ended by other means. However, the NhRP’s work so far has focused on charismatic, highly intelligent animals (chimpanzees and elephants, in particular). While the NhRP’s legal arguments are based on a right to liberty that they believe could be claimed for many animals,69 it seems likely that, in practice, animals who are easiest for judges, legislators, and citizens to recognize as humanlike will be more likely to be granted rights. In that case, the NhRP’s impact could be limited.

Strategic planning process

The NhRP does its strategic planning via regular meetings (once or twice annually) in which the board and the organization’s directors come together to discuss how their activities relate to the charity’s mission. At the end of the process, they set short-term goals for a one-year and five-year timeline.70 They have told us that they require consensus in their decision making and pride themselves on resolving disagreements through intense and evidence-based debates.71

Goal setting and monitoring

Choplin describes the NhRP’s process for monitoring progress as “organic.” After major events like receiving a ruling, the NhRP typically steps back for the next couple of weeks to discuss their work and how to proceed. They also monitor law review publications and media coverage, including key terms. Since they began using petitions, they use signatures as a measure of engagement.72

It’s our impression that the NhRP could put a more focused effort into (i) identifying shorter-term goals and metrics, and (ii) following up on those goals more formally at regular intervals. However, we recognize that they face a particular challenge in this area given the long-term nature of their mission.

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Overall Assessment:

The most effective charities have healthy cultures and sustainable structures to enable their core work. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about the culture they try to foster and their perceptions of staff morale. We review each charity’s policies related to human resources and check for essential items. We also send each charity a culture survey and request that they distribute it among their team on our behalf.

Human Resources Policies

Here we present a list of policies that we find to be beneficial for fostering healthy cultures. A green mark indicates that the NhRP has such a policy and a red mark indicates that they do not. A yellow mark indicates that the organization has a partial policy, an informal or unwritten policy, or a policy that is not fully or consistently implemented. We do not expect a given charity to have all of the following policies, but we believe that, generally, having more of them is better than having fewer.

| A workplace code of ethics that is clearly written and consistently applied throughout the organization | |

| Paid time off Staff are permitted to take vacation time as needed. |

|

| Sick days and personal leave Staff receive 48 hours of sick time per year that can accrue to a maximum of 72 hours. |

|

| Full healthcare coverage The NhRP offers a healthcare reimbursement account. |

|

| Regular performance evaluations | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| A formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries |

| A written statement that they do not discriminate on the basis of race, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A written statement supporting gender equity and/or discouraging sexual harassment | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| An optional anonymous reporting system | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment or discrimination through all levels of the managerial chain up to and including the Board of Directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| A practice in place of documenting all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular, mandatory trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) | |

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for submitting reasonable accommodation requests | |

| Remote work option |

| Audited financial documents (including the most recently filed IRS form 990, for U.S. organizations) made available on the charity’s website | |

| Board meeting notes made publicly available | |

| Board members’ identities made publicly available | |

| Key staff members’ identities made publicly available |

| Formal orientation provided to all new employees | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Funding provided for books or other educational materials related to each employee’s work | |

| Paid trainings available on topics such as: diversity, equal employment opportunity, leadership, and conflict resolution | |

| Paid trainings in intercultural competence (for multinational organizations only) | n/a |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support |

Culture and Morale

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly towards all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. Lauren Choplin, the NhRP’s Communications Director, describes the organization’s culture as “collaborative, open, and accommodating,” noting that everyone “gets along well” and is respectful of one another.73 This is consistent with the results of our culture survey. Out of six respondents, five described the NhRP’s internal communication style as “open,” “honest,” or “candid.” Four respondents described the culture as “collaborative” or “respectful.” Our survey suggests that the NhRP has a very high level of employee engagement.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion74

One important part of acting responsibly towards stakeholders is providing a diverse,75 equitable, and inclusive work environment. Charities with a healthy attitude towards diversity, equity, and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, which improves their ability to respond to new situations and challenges.76 Among other things, inclusive work environments should also provide necessary resources for employees with disabilities, require regular trainings on topics such as diversity, and protect all employees from harassment and discrimination.

The NhRP has not taken proactive measures to recruit a diverse team77 or to promote a healthy attitude towards diversity, equity, and inclusion within their organization. Choplin points out that their Executive Director and President are both white men, though they do have more women than men on their staff.78 We think that the NhRP would benefit from promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion more proactively, perhaps with the help of an external organization such as Encompass.

Sustainability

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in leadership. The charity should not seem likely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, it should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

The NhRP is mostly supported by donations, though they received one grant from the NoVo Foundation to support them over the past two years.79 A relatively high portion of the NhRP’s budget comes from a small number of donors.80 In 2018, the NhRP hired a Development Director to enable them to expand and pursue legislative initiatives and campaigns.81 We hope they will continue to expand their donor base and their number of recurring donors, which would help increase the stability of their finances.

Note that we are never 100% confident in the effectiveness of a particular charity or intervention, so three gray circles do not necessarily imply that we are as confident as we could possibly be.

We found that charities interpreted the question of how many assets they had very differently. Some interpreted assets as financial reserves, some as net assets, and some as material assets. We have interpreted assets as financial reserves, which we calculated by taking the assets from the previous year, adding the (estimated) revenue for the current year, and subtracting the (estimated) expenses for the current year.

Sources:

2014–2017 revenue, assets and expenses: ProPublica, n.d.

2018 revenue, assets, and expenses: Nonhuman Rights Project, 2019

2019 first six months of revenue and expenses: Nonhuman Rights Project, 2019We have included all financial information available from 2014 until mid-2019.

We assume that charities receive an estimated 40% of their revenue in the last two months of the calendar year. To calculate estimates of total revenue, we multiply the revenue from the first six months by 2.778. We assume that expenses stay constant over the year, so to calculate estimates of total expenses in 2019, we multiply expenses from the first six months by 2.

For simplicity and for keeping the model as consistent as possible between charities, we chose to project future financials based on past financials, and exclude additional plans or fundraising goals.

In combination with our estimates of the priority level and costs of each planned expansion, the estimates are based on charities’ own estimates of planned expansion as expressed in our follow-up questions for them (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019).

See ACE’s 2019 cost-effectiveness estimates spreadsheet.

Potential bottlenecks besides lack of funding include lack of operational capacity to support new staff members and difficulty to find and hire value-aligned individuals with the right skill sets. We base our estimates for capacity for expanding staff based on the current number of staff employed, as reported in Nonhuman Rights Project (2019). NhRP employs 7 full-time staff and 5 part-time staff. Based on this, our subjective assessment is that we are highly confident that NhRP can hire 37% of the new staff they would like to hire before running into non-funding related bottlenecks. For 63% of the hires, we believe the non-funding related bottlenecks play a more significant role and we are only moderately confident that NhRP can overcome these bottlenecks within the next year. Therefore, we estimate that 37% of new hires are high priority and 63% are moderate priority.

NhRP noted that they would like to hire for the following roles in the next year:

– Staff Attorney

– Volunteer Coordinator

– Campaigns Manager

– Communications Manager

– Database and Online Advertising Manager

– In-House Videographer

– Science Group Manager

– Additional Consulting Attorneys (for international work)

(Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019)We base our salary estimates on the NhRP’s Form 990 from 2017 (ProPublica, n.d.). They note that in 2017, they employed seven people and spent $261,120 on salaries. This would mean that, on average, staff members at the NhRP earn $37,303 per year. NhRP notes their salaries are higher than our estimates predict (L. Choplin, personal communication, November 26, 2019). Because no other source for salaries at the NhRP is available at the time of writing, we use our own estimates in our analysis, which may be an underestimation. We add room for uncertainty of ± 20%. To estimate the total expenses related to hiring a new staff member, we multiply the salary with a distribution of 1.5 to 2.5 to account for recruiting expenses, employment taxes, benefits, training, equipment, etc. To account for the fact that people will be hired throughout the year and not only at the beginning, we multiply the expenses by a distribution of 0.25 to 1.25.

This is based on data from SquareFoot for an office between two and seven employees (French, 2015).

Costs include “[w]ebsite development (better highlighting victories, important cases/rulings, educational resources)” and “[h]osting nonhuman rights teach-ins in as many cities as possible across the U.S.” (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019).

To estimate the revenue not influenced by ACE, we consider the total revenue per year and subtract the amount we estimate is influenced by ACE in the same year. We use these numbers to estimate the average growth not influenced by ACE. To calculate the estimated 2020 revenue, we add the average growth not influenced by ACE to the 2019 revenue not influenced by ACE. In the case of the NhRP, the amount of revenue influenced by ACE was $95k between the beginning of 2016 and mid-2019. For details, see our giving metrics reports from 2016, 2017, and 2018. At the time of writing, our 2019 Giving Metrics Report is not yet published.

The total revenue is based on the first six months of 2019 with an uncertainty of ± 10%.

The calculations on which this estimate is based exclude revenue influenced by ACE, and have an uncertainty of ± 20%. The calculations are made via a linear projection of the total revenue of previous years.

While we are able to corroborate some types of claims (e.g., those about public events that appear in the news), others are harder to corroborate. For instance, it is often difficult for us to verify whether a charity worked behind the scenes to obtain a corporate commitment, or the extent to which that charity was responsible for obtaining the commitment.

Since we did not ask charities to provide details about accomplishments prior to 2018, key results before this year were sourced from publicly available information and may be incomplete.

Although the NhRP was denied a Motion for Permission to Appeal to the New York Court of Appeals in one of Tommy’s and Kiko’s cases, Judge Eugene M. Fahey stated: “to treat a chimpanzee as if he or she had no right to liberty protected by habeas corpus is to regard the chimpanzee as entirely lacking independent worth, as a mere resource for human use, a thing the value of which consists exclusively in its usefulness to others” (State of New York Court of Appeals, 2018).

See the timeline of Tommy’s case (Nonhuman Right Project, n.d.), the timeline of Kiko’s case (Nonhuman Rights Project, n.d.), and the timeline of Hercules and Leo’s case (Nonhuman Rights Project, n.d.).

The judge’s opinion about this case featured in several media outlets, including the Independent (Turner, 2018), Gizmodo (Dvorsky, 2018), Forbes (Morris, 2018), and The Washington Post (Brulliard, 2018).

See the timeline of Beulah, Karen, Minnie’s case (Nonhuman Rights Project, n.d.).

See the timeline of Happy’s case (Nonhuman Rights Project, n.d.).

According to the NhRP, this was the second habeas corpus issued on behalf of non-human animals in the U.S.; the first was NhRP chimpanzee clients Hercules and Leo (Choplin, 2018).

The NhRP reports the habeas corpus petition on behalf of Chucho was modeled on NhRP U.S. litigation (Nonhuman Rights Project, 2019).

Since we did not ask charities to provide details about accomplishments prior to 2018, key results before this year were sourced from publicly available information and may be incomplete.

The NhRP reports the articles had a potential reach of 1.23 billion worldwide, as indicated by their media monitoring service Meltwater (Nonhuman Rights Project, 2019).

See Voiceless Australia resources for high-school educators (Voiceless, n.d.).

For the full list of publications, see Nonhuman Rights Project (n.d.).

The NhRP reports the Connecticut hearing alone (about the three elephants) generated 500 media mentions with a collective potential reach of 200 million people (Nonhuman Rights Project, 2019).

NhRP reports that Wise gave a talk at the official launch of Cambridge Center for Animal Rights Law (Nonhuman Rights Project, 2019).

Since we did not ask charities to provide details about accomplishments prior to 2018, key results before this year were sourced from publicly available information and may be incomplete.

The NhRP reports that the media coverage of one rally included the New York Daily News, the New York Post, Evening Standard, Fast Company, NY1, and Bronx 12, which prompted journalist Yashar Ali to publish a series of Tweets targeting local elected officials. Within hours, the Twitter thread received 25,000 likes and 15,000 retweets. A few weeks later, New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson issued a powerful statement in support of Happy’s release following a conversation that the NhRP coordinated between Speaker Johnson and Dr. Joyce Poole, one of the NhRP’s elephant experts (Nonhuman Rights Project, 2019).

The NhRP reports the coverage of their litigation and grassroots advocacy campaigns on behalf of one of their elephant clients had a collective potential reach of over 40 million people in the first half of 2019 (Nonhuman Rights Project, 2019).

Note that some charities’ programs do not fit in well with the rest of the reviewed charities according to our categorization of intervention type.

For a longer discussion of the limitations of modelling cost-effectiveness, see Šimčikas (2019).

To estimate their 2019 expenditures, we doubled the financial data provided from January–June 2019.

This includes all charities reviewed in 2019 that are engaged in a program related to legal advocacy.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allows us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost-effectiveness. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work. We think it is unlikely that, in practice, volunteers are working full-time weeks, however we are using this unit in order to maintain a comparison with the amount of staff time used.

This includes all charities reviewed in 2019 that are engaged in a program related to media campaigns.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. This allows us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost-effectiveness. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work. We think it is unlikely that, in practice, volunteers are working full-time weeks, however we are using this unit in order to maintain a comparison with the amount of staff time used.

We recognize at least two major limitations of our culture survey. First, the NhRP has a very small team. The staff members they identified as the organization’s leadership make up three out of the five respondents who took the survey, and they could have skewed the results. Second, all respondents knew that their answers could influence ACE’s evaluation of their organization. They may have felt an incentive to emphasize their organization’s strengths and minimize their weaknesses.

We distributed our culture survey to the NhRP’s nine team members and six responded, for a response rate of 66%.

Our goal in this section is to evaluate whether each charity has a healthy attitude towards diversity, equity, and inclusion. We do not directly evaluate the demographic characteristics of their employees. There are at least two reasons supporting our approach: First, we are not well-positioned to evaluate the demographic characteristics of each charity’s employees. Second, we believe that each charity is fully responsible for their own attitudes towards diversity, equity, and inclusion, but the demographic characteristics of a charity’s staff may be influenced by factors outside of the charity’s control.

We use the term “diversity” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of any of the following characteristics: racial identification, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, ability levels, educational levels, parental status, immigrant status, age, and/or religious, political, or ideological affiliation.

There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that teams composed of individuals with different roles, tasks, or occupations are likely to be more successful than those which are more homogeneous (Horwitz & Horwitz, 2007). Increased diversity by demographic factors—such as race and gender—has more mixed effects in the literature (Jackson, Joshi, & Erhardt, 2003), but gains through having a diverse team seem to be possible for organizations which view diversity as a resource (using different personal backgrounds and experiences to improve decision making) rather than solely a neutral or justice-oriented practice (Ely & Thomas, 2001).