Wild Animal Initiative

Working to understand and improve the lives of wild animals.

$4.7M

in research funding awarded to 72 projects since 2023

16

peer-reviewed publications since 2023

170

new members recruited to their Research Community in 2024

1

university course influenced to add wild animal welfare science in 2024

About Wild Animal Initiative

Wild Animal Initiative works to improve our understanding of wild animals’ lives by advancing the field of wild animal welfare science. They conduct their own research and support other wild animal researchers to expand academic interest in wild animal welfare. Together, these efforts help uncover evidence-based solutions to improve the wellbeing of wild animals. See why ACE recommends Wild Animal Initiative in the video below.

Wild Animal Initiative at a Glance (2025)

Founded

2019

Revenue (2024)

$3.8 million

Growth

Can effectively absorb $6.9 million per year in 2026 and 2027.

Outcomes

Works to improve welfare of wild animals globally.

Scope

Supports research and field building, with the potential to help millions of animals each year.

Direction

Demonstrates strong reasoning and a data-driven strategy.

What is the unique problem?

The vast majority of animals—multiple trillions—live in the wild, where many experience short lives and painful deaths from causes such as disease, hunger, and predation. Very little is known about the quality of life of these animals, or how to improve it. Scientific progress is urgently needed to identify the factors that cause the most severe suffering for wild animals, and to determine how to address those factors responsibly, effectively, and at scale.

How does Wild Animal Initiative solve it?

Wild Animal Initiative is the only charity dedicated to accelerating wild animal welfare science. Recognizing that knowledge gaps are too vast for any single research group, WAI fosters a robust, diverse community of scientists to address urgent questions about wild animals’ welfare. Their approach combines conducting original research, awarding grants, and supporting researchers studying wild animal welfare. This comprehensive strategy positions them to identify ways to reduce suffering for trillions of wild animals affected by both human and natural causes.

Recent Key Achievements

Awarded funding to research critical areas, including welfare indicator validation, fish and invertebrate welfare, and near-term interventions.

Achieved a new level of academic recognition for wild animal welfare science, via a dedicated day at the Animal Welfare Research Network meeting and the launch of a seminar series coordinated by WAI, the Royal Veterinary College, and the Zoological Society of London.

Contributed to 16 scientific conferences, presenting interactive workshops, posters, and talks.

Why We Recommend Wild Animal Initiative

Wild Animal Initiative advances wild animal welfare science through research, strategic grants, and academic outreach. This multi-pronged approach builds scientific foundations and cultivates a diverse research community. While their pathway to impact is more indirect and longer term compared to other charities, their theory of change is convincing. We see that WAI is achieving early-stage outcomes, and we believe their work has strong potential to help large numbers of wild animals. We consider them a high-priority giving opportunity.

What Others Say

“A lot of scientists like me were always interested in welfare, but unless it was captive animals, pets, or agriculture; you really couldn’t work on it. And I think that’s changed—I really think Wild Animal Initiative has encouraged a whole rethink of what’s possible.”

Ross MacLeod

WAI Grantee

“We need a dedicated field of wild animal welfare science to understand and improve the lives of wild animals responsibly and at scale. Wild Animal Initiative has played a transformative role in building this field—including supporting the creation of the New York University Wild Animal Welfare Program—and I’m excited to keep collaborating with them as they work toward even greater impact.”

Jeff Sebo

Co-Director of the Wild Animal Welfare Program at New York University

How Wild Animal Initiative will use any future donations

Additional donations would enable Wild Animal Initiative to partner with Conservation X Labs to accelerate research and development for rodent contraception, a top funding priority. They would also expand their fundraising capacity and program staff to strengthen their services.

Wild Animal Initiative's future outlook

In the years ahead, Wild Animal Initiative will work to engage more scientists in advancing wild animal welfare and addressing critical research needs. The organization aims to present their findings at leading conferences, publish additional research papers in academic journals, and establish new partnerships with research institutions to expand their reach and strengthen the field.

This review is based on our assessment of Wild Animal Initiative’s performance on ACE’s charity evaluation criteria. For a detailed account of our evaluation methods, including how charities are selected for evaluation, please visit our How We Evaluate Charities web page.

Overall Recommendation

Wild Animal Initiative (WAI) focuses on improving wild animal welfare globally. Their programs combine grant making, research, and scientific outreach into a convincing and logical theory of change focused on building a self-sustaining academic field to address the vast knowledge gaps in wild animal welfare science. Their programs are strategically designed to complement and reinforce each other to target key field-building bottlenecks. There are promising early signs that their theory of change is progressing across their programs.

Our assessment of WAI’s programs indicates that they have executed their activities cost effectively to date. Due to the high uncertainty inherent in their long-term, field-building work, we did not estimate animals affected per dollar. However, speculative modeling suggests that under reasonable and conservative assumptions, their cost effectiveness is competitive with that of Recommended Charities doing more direct work. Given the uncertainty in this approach, we place relatively more weight on their strong theory of change.

WAI’s plans for how they’d spend additional funding across 2026 and 2027 give us confidence that they would use additional funding in effective ways that reduce suffering for a large number of animals. We had no decision-relevant concerns about their organizational health. Overall, we expect Wild Animal Initiative to be an excellent giving opportunity for those looking to create the most positive change for animals.

Overview of Wild Animal Initiative’s Programs

During our charity selection process, we looked at the groups of animals Wild Animal Initiative (WAI)’s programs target and the countries where their work takes place. For more details about our charity selection process, visit our Evaluation Process web page.

Animal groups

WAI’s programs focus exclusively on helping wild animals, which we assess as a high-priority cause area.

Countries

WAI is based in the United States, but conducts their work globally.

Interventions

WAI uses different types of interventions to create change for animals, including wild animal welfare research, providing funding, skill building, and network building. See WAI’s theory of change analysis for evidence of the effectiveness of their main interventions.

Impact

What positive changes is WAI creating for animals?

To assess WAI’s overall impact on animals, we looked at two key factors: (i) the strength of their reasoning and evidence for how their programs create change for animals (i.e., their theory of change) and (ii) the cost effectiveness of select programs. Charities that use logic and evidence to develop their programs are highly likely to achieve outcomes that lead to the greatest impact for animals. Charities with cost-effective programs demonstrate that they use their available resources in ways that likely make the biggest possible difference for animals per dollar. We also conducted spot checks on a sample of the charity’s most decision-relevant claims, such as their reported achievements, to confirm their accuracy. For more detailed information on our 2025 evaluation methods, please visit our Evaluation Criteria web page.

Our assessment of Wild Animal Initiative’s impact

Based on our theory of change assessment, which includes an evaluation of logical reasoning and evidence and considers assumptions, we are strongly convinced that WAI’s programs are creating positive change for wild animals.

Our uncertainty in this assessment is moderate-to-high due to the long-term and indirect nature of WAI’s theory of change and the reliance on shifting contexts and other actors largely outside of WAI’s control, which makes later-stage outcomes inherently speculative. Furthermore, due to the complexity of WAI’s theory of change compared to other charities we evaluated, we were only able to look into a smaller proportion of the assumptions and paths we thought were most crucial to their impact. Finally, the assessment relies heavily on expert testimony, case studies, and theoretical reasoning due to a lack of robust empirical studies on the effectiveness of academic field building.

The most important considerations informing this verdict were:

- (+) Although there was some disagreement among sources, on balance, the strategy of focusing on academic field building (rather than only funding individual studies) appears to be a logical and highly-leveraged approach. Given the vast knowledge gaps in wild animal welfare, WAI cannot fill them alone; developing a self-sustaining academic field is a rational long-term strategy to generate the required research at scale.

- (+) There are promising early signs that the theory of change is progressing across different programs, with the intended feedback loops beginning to function. For example, their Grants program is seeding new researchers who then engage with their Outreach program, and conference outreach has led to new grantee collaborations and influenced the direction of subsequent grants.

- (-) The path from generating academic knowledge to implementing real-world interventions faces immense external hurdles. WAI’s success is ultimately contingent on other actors (e.g., policymakers and advocacy groups) taking action on their research, a step WAI acknowledges is largely outside their direct control.

- (+) WAI’s programs strategically target a key, expert-confirmed bottleneck for the field: the lack of validated welfare metrics. Both their Grants and Research programs are logically focused on this issue and are showing promising emerging evidence of success. (-) However, there is not yet evidence that these metrics are widely used by researchers in the field.

- (+) A key strength of WAI’s approach is their high degree of strategic intentionality. Their programs are explicitly designed as an integrated system, with research, grantmaking, and outreach activities reinforcing each other to help establish a new academic field of wild animal welfare science. This goal-focused approach is also evident in their proactive risk management and their use of data and evidence to guide decision making.

- (-) There is very limited evidence for the effectiveness of the Outreach program in achieving its later-stage outcomes. While WAI tracks outputs like event participation, data to confirm that this is successfully advancing desired outcomes—such as an increase in independent collaborations or new researchers joining the field—is currently lacking, anecdotal, or unsystematic, making it difficult to assess the program’s overall impact.

Our cost-effectiveness assessment focuses on all three of WAI’s programs: Grants, Outreach, and Research. Due to WAI’s particularly long-term and indirect theory of change, the speculative nature of key inputs, and limited data and empirical evidence, we were unable to produce reliable estimates of Suffering-Adjusted Days (SADs)1 averted per dollar. However, we can share the following insights:

Based on the relative program expenditures, we estimate that for each $1 million spent on WAI’s programs overall, they are able to produce all of the following results:

- Grants program:

- 5 completed grantee research projects

- 4 peer-reviewed papers published

- 1 new welfare metric validated

- Outreach program:

- 50 new research community members

- 181 event participants

- 28 individuals trained in wild animal welfare concepts and methods

- 5 new educational resources

- 120 individuals reached through educational resources

- 1 meeting with university staff

- 0.3 university course or module newly including wild animal welfare science

- 1 university conference newly including wild animal welfare science

- Research program:

- 2 research projects completed

- 2 peer-reviewed papers published

- 65 views on research reports (over 2.5 years)

We view these results not as final outcomes, but as indicators that WAI’s long-term strategy is progressing. To gauge the potential scope of WAI’s work, we made a series of speculative assumptions about how these tangible achievements might accelerate the growth of the wild animal welfare science field and, eventually, lead to large-scale reductions in animal suffering. Because these factors are highly uncertain, we ran the model through many iterations, using a range of assumptions from conservative to more optimistic. We found that even when using what we consider to be reasonable and conservative assumptions, the projected long-term impact of WAI’s work is plausibly cost competitive with the more immediate impacts of our other Recommended Charities.

However, due to this particularly high level of speculation, we gave only limited weight to this cost-effectiveness analysis in our overall assessment of WAI.

WAI’s key paths to impact

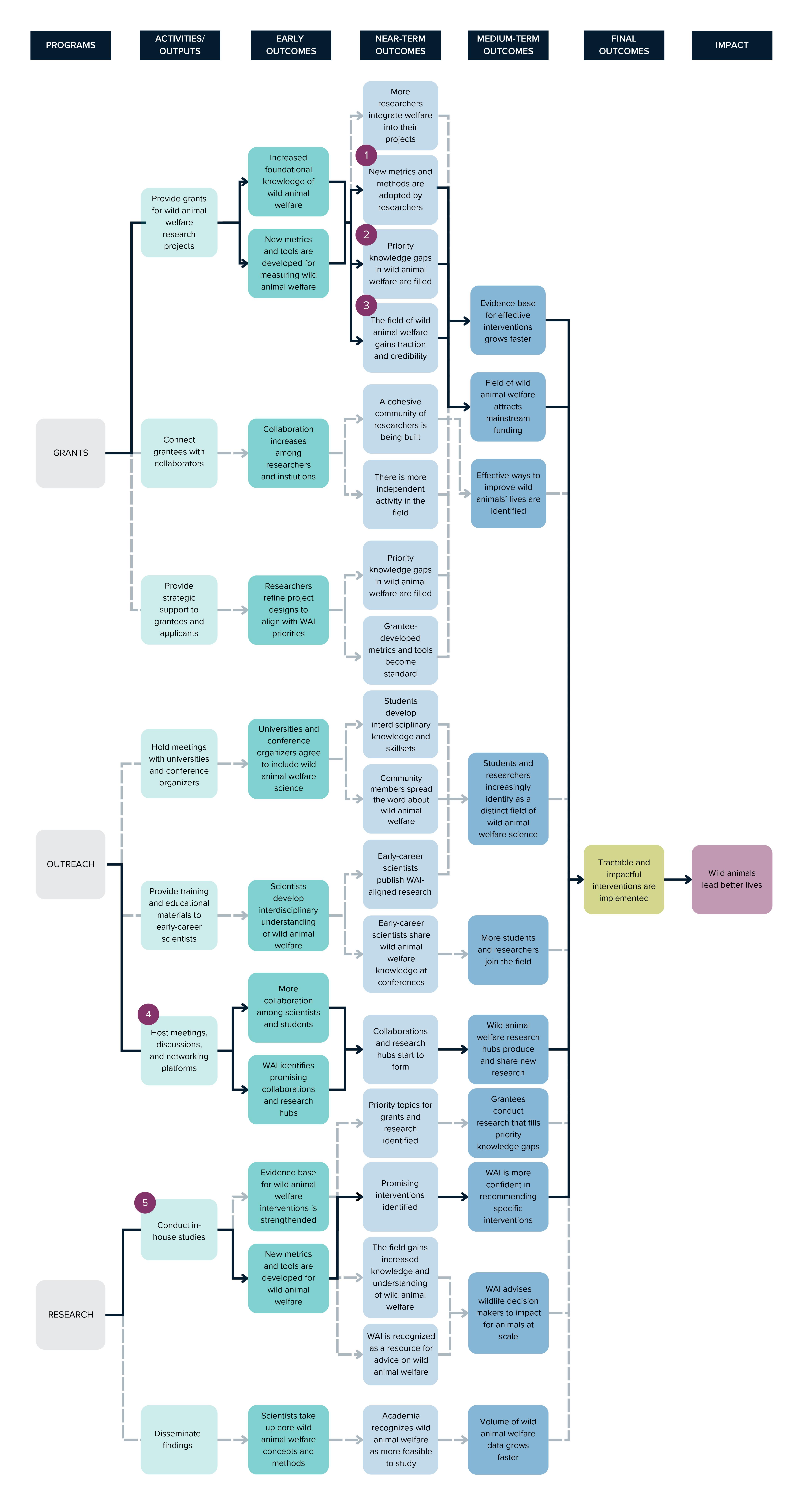

Figure 1: Simplified diagrammatic representation of how Wild Animal Initiative creates change for animals. Note: The key paths discussed below correspond to the numbered paths in the diagram above.

Key paths 1 and 3—Research grants to fill key knowledge gaps and develop welfare metrics

WAI provides grants to fund wild animal welfare research with the aim of building core knowledge for the field. They intend for these efforts to grow the evidence base for effective wild animal welfare interventions faster than it would organically, eventually enabling the development and implementation of tractable interventions that improve wild animals’ lives.

Overall assessment

The experts we consulted agreed that gaps in foundational knowledge and a lack of welfare assessment methods for wildlife are crucial bottlenecks to developing effective interventions. The logic of Key Paths 1 and 3 is sound and compelling, and the track record of the program shows that grantees are consistently producing research that builds foundational knowledge and they have also validated a few welfare metrics. Additionally, we expect that the relevant evidence will be built over time. However, since WAI’s theory of change is particularly long term, we have less evidence for the medium-term and final outcomes and impact, such as relevant knowledge gaps being filled and welfare metrics being widely used in the community.

Most importantly, given the vast knowledge gaps in this field, significant progress would be highly challenging if it were limited to WAI’s resources alone. We therefore think that WAI’s impact may come primarily from their efforts to help the field of wild animal welfare science gain traction and credibility, rather than from the knowledge directly gained from WAI-funded research. WAI’s strategic grantmaking likely contributes to this field-building strategy (see Key Path 2) and it may also be a useful way to steer the emerging field in an impact-focused direction.

Based on our evaluation of the logical reasoning, evidence, and assumptions, we are moderately convinced that providing research grants can reliably lead to tractable interventions for animals in the future by filling important knowledge gaps now. Our uncertainty in this verdict is moderate-to-high due to a lack of evidence for later stages in the path and some disagreement between the sources and external experts we consulted.

Key path 2—Providing research grants to increase the traction and credibility of the field

Another intended outcome of WAI’s grantmaking is to increase the traction and credibility of the field of wild animal welfare science. They aim to help the field attract significant mainstream funding, enabling larger-scale research and action to develop and implement interventions that improve wild animals’ lives.

Overall assessment

There is some proxy evidence of early-stage field building for wild animal welfare science, such as the increase in academic publications with a welfare focus. It’s plausible that this trend will continue. What is more uncertain is whether WAI’s Grants program itself is a large contributor to growing the traction and credibility of the wild animal welfare science field, but given the size of the field prior to WAI’s interventions, and the absence of significant other funding opportunities, the logic model of their counterfactual role is strong. Wild Animal Initiative also provided data indicating that their grant program successfully attracts academics who previously did not focus their research on animal welfare.

There is also some early evidence of mainstream funders becoming interested in wild animal welfare science, at least when instrumentally framed: WAI provided the compelling example of New York University successfully securing mainstream funding by framing a project to emphasize its environmental and One Health2 co-benefits, and gave WAI direct credit for making that possible.

Based on our evaluation of the logical reasoning, evidence, and assumptions, we are strongly convinced that providing research grants can reliably lead to successful interventions for animals by building traction and credibility for the field of wild animal welfare science. Our uncertainty in this verdict is moderate-to-high due to a lack of evidence for the later stages of their theory of change and the fact that we only have emerging evidence for the earlier stages. Precisely gauging WAI’s counterfactual impact on the early field-building developments is also challenging.

Key path 4—Conducting in-house studies to develop welfare metrics

In their in-house Research program, WAI focuses on neglected areas to shape the field of wild animal welfare science, guide future advancements, and encourage external scientists to engage. They also develop and validate new welfare metrics so the field learns how to measure and model wild animal welfare, leading to the development and implementation of effective interventions for wild animals.

Overall assessment

It is logical for WAI to use their in-house Research program to develop new welfare metrics; experts largely agree that this is a key bottleneck for the field. The research is leading to a steady stream of peer-reviewed publications that are being cited by the scientific community—promising evidence that this path is progressing. They have successfully validated two welfare metrics, and have nearly completed a third.3

Overall, the Research program is making some measurable progress in the early, foundational stages of this path. However, WAI’s team has limited capacity, and the tangible output of new, field-ready empirical tools remains low to date. The program’s main successes in this area have been conceptual and review based, which are crucial foundational steps, but are distinct from creating new, field-ready measurement tools. There is currently also limited evidence of WAI’s tools being adopted by the research community or practitioners.

Based on our evaluation of the logical reasoning, evidence, and assumptions, we are moderately convinced that conducting in-house research projects can reliably lead to tractable interventions for animals by developing welfare metrics and measuring tools. Our uncertainty in this verdict is moderate-to-high due to a lack of evidence for the later stages of their theory of change, and uncertainty around the research community adopting the tools that are developed. Due to capacity constraints, we also weren’t able to look into WAI’s in-house research portfolio in depth, or to assess evidence of successful relationships with adjacent fields, which is likely necessary to build credibility for WAI’s research and tools.

Key path 5—Hosting events and networking platforms to foster collaboration

As part of their Outreach program, WAI hosts meetings, discussions, and a networking platform (i.e., their Research Community) to provide opportunities for researchers to present their work and connect with others working to improve our understanding of wild animals’ welfare. WAI intends for these collaborations to eventually formalize and develop into independent research hubs.

Overall assessment

Creating independent research institutions is crucial to reaching a self-sustaining field with sufficient capacity, and their outreach work is a logical approach. However, there is currently no concrete evidence that the later stages of this path are bearing out, i.e., that the outreach activities encourage independent collaborations among researchers. Understandably, this type of field-building work will take time, but the lack of data is in part also due to a lack of systematic tracking of collaborations that don’t directly involve WAI. WAI provided anecdotal evidence of new collaborations emerging from their events, and there are some promising early developments on establishing research hubs at a number of universities.

Based on our evaluation of the logical reasoning, evidence, and assumptions, we are moderately convinced that hosting events and networking platforms can reliably lead to independent research hubs by fostering collaboration in the field. Our uncertainty in this verdict is moderate-to-high due to a lack of data on most of the expected outcomes of this activity. With more time, we would have consulted more individuals who are familiar with their Research Community.

Additional considerations

Key overarching assumptions and risks

- A cross-cutting key assumption behind WAI’s theory of change is that stakeholders, such as wildlife managers and conservation groups, will eventually implement interventions that help wild animals effectively. We are moderately convinced this assumption holds, because the path to implementation faces external hurdles that WAI has limited influence over. We think implementation is most tractable in areas with clear co-benefits for human goals, and will depend on parallel advocacy and policy work. While scientific progress is not sufficient by itself, we see it as a necessary condition for the implementation of large-scale effective interventions for wild animals in the future.

- Another key assumption is that building a new academic field is a better use of resources than funding the few currently-available interventions. We are overall convinced this is a reasonable long-term strategy because it offers a leveraged approach to creating a self-sustaining field that can help normalize the cause with limited funding.

Risk assessment strategy

We have no concerns about WAI’s risk management, and we find their approach to be robust and proactive. They identify critical long-term risks—such as reputational harm and creating an ineffective field—and integrate mitigation directly into their core strategy. This is evident in everything from their high research standards to their specific grantmaking priorities.

Use of empirical evidence in decision making

WAI’s approach to using evidence is strong, as shown by the strategic feedback loop between their Grantmaking and in-house Research programs. They use data from the grant proposals they receive to direct their in-house research toward the most neglected questions. In turn, the findings from that research are used to resolve strategic uncertainties and guide future grantmaking. This allows them to build a solid empirical foundation for the field while continuously optimizing how they direct their limited funds.

Use of Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) data to inform decisions

WAI’s approach to MEL involves a central data hub to systematically track program outputs, such as grantee publications and conference participation, as well as the overall “state of the field.” We think this approach is systematic and strategic. However, a key limitation is that their data currently focuses on early-stage outputs, with more limited evidence to confirm they are advancing desired later-stage outcomes like increased collaboration within the field. This is largely inherent to the long-term nature of their theory of change, but we do think that for their Outreach program, WAI should try to collect more systematic data to confirm whether these activities are successfully fostering new collaborations or bringing new researchers into the field.

Strategic selection of programs to complement and support each other

We find that WAI’s strategy of integrating their three core programs is logical and sound. The programs are designed as a reinforcing feedback loop: the Research program prioritizes key topics, the Grants program kickstarts the field by funding external researchers based on those priorities, and the Outreach program sustains the resulting community.

Contribution of programs to the wider animal advocacy movement

WAI’s primary contribution to the advocacy movement is to establish wild animal welfare as a legitimate academic field. This strategy aims to provide advocates with a credible scientific foundation, moving the issue from the realm of personal ethics to objective science, and giving them evidence to support their campaigns. We assess this focus on legitimacy as a key strength, but an immediate challenge is that the wild animal advocacy movement is very small, so additional movement-building work is likely necessary to build the capacity to use the scientific findings in practice.

See WAI’s cost-effectiveness spreadsheet for a detailed account of the data and calculations that went into our cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA).

- We included all three of WAI’s programs in our analysis: (i) Grants, (ii) Outreach, and (iii) Research. For this analysis, we were unable to model the ultimate impact on animals and instead estimated the cost efficiency of each program. This measures the cost of producing key outputs (e.g., a published paper or a training resource), rather than the cost effectiveness of achieving ultimate outcomes (e.g., suffering reduced). Since a deep analysis of one program’s final impact was not feasible, we opted for this broader approach to provide a more comprehensive view of how efficiently each of WAI’s core programs operates.

- Program 1: Grants

- We estimate that for each $1 million spent, the Grants program is able to produce all of the following results:

- 8 completed grantee research projects

- 7 peer-reviewed papers published

- 1 new welfare metric validated

- See here for qualitative information on the impact these might have.

- Limitations:

- We were unable to reach an estimate of Suffering-Adjusted Days (SADs) averted per dollar. This is due to the indirect, long-term, and speculative nature of WAI’s work. Most of their activities focus on foundational field building, and attributing specific, large-scale future welfare improvements solely to this early-stage work is extremely challenging.

- We are also somewhat uncertain about the operational costs of this program. WAI’s reported operational costs are much lower than our estimated costs based on a proportional distribution of overall overhead across WAI’s programs. We went for the latter because the overhead would otherwise be disproportionately added to the other two programs.

- Several inputs to our cost-effectiveness analysis are based on WAI’s own estimates.

- We estimate that for each $1 million spent, the Grants program is able to produce all of the following results:

- Program 2: Outreach

- We estimate that for each $1 million spent, the Outreach program is able to produce all of the following results:

- 214 new research community members

- 780 event participants

- 119 individuals trained in methods and concepts of wild animal welfare

- 20 new educational resources

- 515 individuals reached through educational resources

- 6 meetings with university staff

- 1 university course or module newly including wild animal welfare science

- 4 university conferences newly including wild animal welfare science

- See here for qualitative information on the impact these might have.

- Limitations:

- As above, we were unable to reach an estimate of SADs.

- We also had to estimate the number of event participants based on event type and size due to a lack of accurate data.

- We estimate that for each $1 million spent, the Outreach program is able to produce all of the following results:

- Program 3: Research

- We estimate that for each $1 million spent, the Research program is able to produce all of the following results:

- 10 research projects completed

- 8 peer-reviewed papers published

- 290 views on research reports (over 2.5 years)

- See here for qualitative information on the impact these might have.

- Limitations:

- As above, we were unable to reach an estimate of SADs.

- A number of inputs to our cost-effectiveness analysis are based on WAI’s own estimates.

- We had less time to spend qualitatively analyzing the potential impact of the research outputs compared to those of the other two programs.

- We estimate that for each $1 million spent, the Research program is able to produce all of the following results:

We view these results not as final outcomes, but as key indicators that WAI’s long-term strategy is progressing. Our process for gauging their potential impact began with a qualitative review of each output type to understand its potential role in the wider field.

For instance, when considering peer-reviewed papers, we looked at their strategic focus (e.g., foundational sentience research or developing a specific methodology) and publication venue (e.g., top-tier general science journals or specialist publications). For research grants, we estimated the potential scope of their applications by considering the abundance of the animals studied and the severity of the suffering addressed. This allowed us to differentiate between outputs with a potentially vast, long-term impact—like a new welfare metric for trillions of insects—and those with a more limited or uncertain scope.

This qualitative review was crucial for the next step: making a series of speculative assumptions for our quantitative model. The insights from the qualitative review informed the range of values we assigned to variables, such as how much a single high-impact paper might accelerate the growth of the field. Because these factors are highly uncertain, we ran the model through many iterations, using a range of assumptions from conservative to more optimistic. We found that even when using what we consider to be reasonable and conservative assumptions, the projected long-term impact of WAI’s work is plausibly competitive with the more immediate impacts of our other Recommended Charities.

However, due to this particularly high level of speculation, we gave limited weight to this cost-effectiveness analysis in our overall assessment of WAI.

Room for More Funding

How much additional money can WAI effectively use in the next two years?

With this criterion, we investigated whether WAI can absorb the funding that a renewed recommendation from ACE may bring, and the extent to which we believe that their future uses of funding will be effective. All descriptive data and estimations for this criterion can be found in the Financials and Future Plans spreadsheet. For more detailed information on our 2025 evaluation methods, please visit our Evaluation Criteria web page.

Our assessment of Wild Animal Initiative’s room for more funding

Based on our assessment of their future plans, we believe that WAI could spend up to $6.9 million in a highly cost-effective way annually in 2026 and 2027, and our assessment of their strategic prioritization makes us confident that they will. This is $3.1 million higher than their projected 2025 revenue. With this additional funding, they would prioritize expanding their fundraising capacity and diversifying their funding, partnering with Conservation X Labs to accelerate rodent contraception research and development, investing in their program staff to strengthen their services, and funding research fellows and hubs at universities.

Future plans

If WAI were to receive additional revenue to expand the organization, they would prioritize using the money to diversify funding sources by hiring a Foundation Relations Manager. Their second priority would be to partner with Conservation X Labs to accelerate rodent contraception research and development by running a workshop and offering a research prize. After that, WAI would invest in their program staff to strengthen their services and fund research fellows and university research hubs. We rated 70% of their projected spending plans as highly effective. Their most promising plans include:

- Expanding fundraising capacity and diversifying funding

- Partnering with Conservation X Labs to accelerate rodent contraception research and development

- Funding up to four research fellows for one year

- Funding research hubs at up to five universities

We rated a few of their plans as moderately effective or below: We were unsure about the added value of general software upgrades or additional staff retreats. We were also uncertain how tractable it would be to partner with two more wildlife groups, and whether WAI would have the capacity and quality of applicants to fund four additional research fellows.

Funding capacity

Based on our assessment of WAI’s future plans, we are confident that they could effectively spend up to a total annual revenue of $6.915 million, which we refer to as their funding capacity.

The chart below shows WAI’s revenues from 2022–2025 and their funding capacity for 2026 and 2027.

WAI Revenue (2022–2025) and Funding Capacity (2026/2027)

Strategic prioritization

Based on how WAI decides which programs to start, stop, scale up, or scale down, we have no concerns about their strategic decision making and believe that they will continue to make cost-effective decisions.

WAI’s high-level strategy is guided by a five-year plan with data-driven annual reviews to assess performance. When allocating funds or scaling programs, decisions are based on maximizing the ‘comparative value of a given dollar,’ ensuring resources flow to the initiatives with the highest potential impact. In their grantmaking, WAI explicitly prioritize projects based on scope (the number of animals affected) and impact (the magnitude of the welfare concern). To ensure a high counterfactual value, they also focus on projects neglected by other funders and use cost effectiveness as a key tie-breaking criterion for equally promising proposals.

Although not all grants funded have a very high scope, this aligns with WAI’s long-term strategy that balances maximizing immediate impact with building a diverse and engaged scientific field. This dual strategy is based on sound reasoning and endorsed by several experts we spoke to.

WAI’s priorities for additional funding appear sensible and strategic, focusing first on ensuring their own long-term stability and second on a tractable, high-scale intervention (rodent fertility control) that is endorsed by experts.

Organizational Health

Are there any management issues substantial enough to affect WAI’s effectiveness and stability?

With this criterion, we assessed whether any aspects of WAI’s leadership or workplace culture pose a risk to their effectiveness or stability, thereby reducing their potential to help animals and possibly negatively affecting the reputation of the broader animal advocacy movement.4 For more detailed information on our 2025 evaluation methods, please visit our Evaluation Criteria web page.

Our assessment of Wild Animal Initiative’s organizational health

We did not detect any major concerns in WAI’s leadership and organizational health. We positively noted that the board has four independent voting members, meets quarterly, board meeting minutes are published on their website, policies are in place for all recommended items, and staff have access to all policies. In the staff engagement survey, staff affirmed that WAI provide a psychologically safe work environment, looks out for equity and inclusion, and supports those with personal illnesses or other issues.

People, policies, and processes

The policies that WAI reported having in place are listed in the table below—policies in bold are those that Scarlet Spark5 recommend as highest priority.

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| COMPENSATION | |

| Paid time off | |

| Paid sick days | |

| Paid medical leave | |

| Paid family and caregiver leave | |

| Compensation strategy (i.e., a policy detailing how an organization determines staff’s pay and benefits in a standardized manner) | |

| WORKPLACE SAFETY | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances | |

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics or conduct | |

| A written statement that the organization does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other irrelevant characteristics | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels, up to and including the board of directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| Documentation of all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Conflict of interest policy | |

| Training on topics of harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| CLARITY, TRANSPARENCY, AND BIAS MITIGATION | |

| Clearly defined responsibilities for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| Clear organizational goals and/or priorities communicated to all employees | |

| New hire onboarding or orientation process | |

| Structured hiring, assessing all candidates using the same process | |

| Standardized process for employment termination decisions | |

| Process to evaluate leadership performance | |

| Performance evaluation process based on predefined objectives and expectations | |

| Two or more decision-makers for all hiring, promotion, and termination decisions | |

| Process to attract a diverse candidate pool | |

| ORGANIZATIONAL STABILITY AND PROGRESS | |

| Documentation of all key knowledge and information necessary to fulfill the needs of the organization | |

| Board meeting minutes | |

| Records retention and destruction policy | |

| Systems in place for continuously learning from the past (e.g., feedback norms, retrospectives) | |

| Recurring (e.g., weekly or every two weeks) 1-on-1s focused on alignment and development | |

| ASSESSMENTS | |

| Annual (or more frequent) performance evaluations for all roles | |

| Annual (or more frequent) process to measure employee engagement or satisfaction | |

| A process in place to support performance improvement in instances of underperformance | |

Transparency

All of the information we required for our evaluation—list of board members; list of key staff members; information about the organization’s key accomplishments; the organization’s mission, vision, and/or theory of change; a privacy policy disclosing how the organization collects, uses, and shares third-party information; an IRS Form 990 tax form; and financial statements—is made available on the charity’s website. WAI also publishes board meeting minutes on their website.

WAI is transparent with their own staff and shares all policies with them.

Leadership and board governance

- Executive Director (ED): Cameron Meyer Shorb, involved in the organization for six years

- Number of board members: Four. Additionally, Wild Animal Initiative has a conflict of interest policy that aims to avoid any potential conflict of interest between the ED and the board.

We found that the charity’s board fully aligned with our understanding of best practice.

About 89% of staff respondents to our engagement survey indicated that they have confidence in WAI’s leadership.

Financial health

Reserves

With over 230% of annual expenditures held in net assets (as reported by WAI for 2024), we believe that they hold a sufficient amount of reserves. They currently exceed their 12-month reserves target.

Recurring revenue

Around 50% of WAI’s revenue is recurring (e.g., from recurring donors or ongoing long-term grant commitments). Based on an external consultation with Scarlet Spark, we find this to be a high proportion of recurring revenue (the ideal being 25% or higher); however, the 25% target is dependent on the context for each charity, so while we have noted this information here, it did not influence our recommendation decision.

Liabilities-to-assets ratio

WAI’s liabilities-to-assets ratio does not exceed 50%.

Staff engagement and satisfaction

WAI has 20 staff members (full time, part time, and contractors). Nineteen of them responded to our staff engagement survey, yielding a response rate of 100%—we did not have their Executive Director take the survey.

WAI has a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. Of the staff who responded to our survey, 89% reported that they are satisfied with their wage. WAI offers a paid-time-off policy, annual sick leave, and family and caregiver leave. About 95% of staff who responded to our engagement survey reported that they are satisfied with the benefits provided.

The average score among our staff engagement survey questions was 4.66 (on a 1–5 scale), suggesting that, on average, staff exhibit very high engagement.

Harassment and discrimination

ACE has a separate process for receiving serious claims about harassment and discrimination, and all WAI staff were made aware of this option. If staff or any party external to the organization have claims of this nature, we encourage them to read ACE’s Third-Party Whistleblower Policy and fill out our claimant form. We received one form submission during our evaluation period. While we take all claims related to organizational health seriously, the details shared with us did not have a meaningful impact on our evaluation of WAI.

To facilitate comparisons across interventions, we attempted to express all cost-effectiveness estimates in terms of SADs averted per dollar. A SAD roughly represents the number of days of intense pain experienced by an animal. Please note that ACE’s 2025 SADs values are not directly comparable with SADs values from previous years or SADs from other organizations.

One Health is an approach that aims to balance and optimize the health of humans, nonhuman animals, and ecosystems (see World Health Organization, n.d.).

These include a meta-analysis to validate oxidative status as a welfare indicator, a metric for integrating age-specific welfare data into an estimate of lifetime welfare (“welfare expectancy”), and a project testing the validity of non-disruptive potential welfare indicators for house sparrows.

For example: Schyns & Schilling (2013) report that poor leadership practices result in counterproductive employee behavior, stress, negative attitudes toward the entire company, lower job satisfaction, and higher intention to quit. Waldman et al. (2012) report that effective leadership predicts lower turnover and reduced intention to quit. Wang (2021) reports that organizational commitment among nonprofit employees is positively related to engaged leadership, community engagement effort, the degree of formalization in daily operations, and perceived intangible support for employees.Gorski et al. (2018) report that all of the activists they interviewed attributed their burnout in part to negative organizational and movement cultures, including a culture of martyrdom, exhaustion/overwork, the taboo of discussing burnout, and financial strain. A meta-analysis by Harter et al. (2002) indicates that employee satisfaction and engagement are correlated with reduced employee turnover and accidents and increased customer satisfaction, productivity, and profit.

Learn more about Scarlet Spark at scarletspark.org/