Leafleting – 2017

Overview

Our 2017 leafleting intervention report is guided by our recently updated intervention evaluation process, which provides a new framework for using multiple sources of evidence to evaluate an intervention’s effectiveness. As such, this report incorporates a variety of methods not used in our previous report, as well as the results of several more recent studies, and reaches quite different conclusions. In particular, based on a meta-analysis combining data from several studies on the short-term effects of leafleting, we conclude that those trials don’t provide clear evidence that leafleting decreases recipients’ animal product consumption in the first few months after distribution. In fact, the results suggest leafleting is about as likely—or perhaps even more likely—to actually cause increases in animal product consumption during this time period. Other evidence1 also supports the conclusion that leafleting is probably less effective than some other promising farmed animal advocacy interventions.

This updated report improves on our previous leafleting report by including, among other things:

- A more systematic literature search

- A detailed assessment of the various risks of bias in the most pertinent animal advocacy studies of leafleting

- A meta-analysis and in-depth discussion of the limitations of those key animal advocacy studies

- A greater discussion of relevant historical evidence and literature from the social sciences

- The incorporation of model uncertainty and a Bayesian prior in our cost-effectiveness estimates

- Information from multiple case studies, as well as interviews with advocates who have a considerable amount of experience with leafleting

An input and some outputs from the the meta-analysis that seem noteworthy are:

- Each of the six randomized controlled field trials included in the meta-analysis was judged to have at least one domain in which the risk of bias was substantial enough to limit our confidence in its results.

- The 95% confidence interval for each of the summary estimates from the meta-analysis overlaps with a point estimate of an effect size of zero. By following the conventionally applied frequentist framework of statistical inference, we would fail to reject the null hypothesis in all cases. In other words, we would not reject the hypotheses that leaflets have no impact on consumption of any of the particular animal products included in the meta-analysis (namely red meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy).

- In most cases, the meta-analysis estimates of change in animal product consumption suggest that leaflets are more likely to cause increases in animal product consumption than decreases in animal product consumption. We think these results support the case that leaflets are likely not very effective; however, we do not think they should be taken as robust estimates of the effects of leafleting.

While the meta-analysis completed in the report was crucial for evaluating the evidence from the particularly relevant field trials and had a large impact on the report overall, it certainly wasn’t the only source of relevant information in the report. Some other points from the updated report that seem noteworthy are:

- If leaflets do have a significant favorable effect on short-term diet changes, then it seems that there is reason to expect that online ads would be more cost-effective than leaflets.

- It is unclear to us just how large a role leaflets have played in social movements where they have been employed. Our limited impression is that relevant Researchers generally don’t seem to think that leaflets played a large role in most social movements, and that leaflets have not been widely considered as an essential part of any other contemporary social movement’s recent work.

- Our cost-effectiveness estimate for leafleting, which is highly uncertain and should be interpreted carefully, had 90% subjective confidence intervals of a decrease in supply of 3 to an increase in supply of 10 farmed animals and a corresponding change of -2 to 2 farmed animal years per dollar spent on leafleting.

Readers are encouraged to refer to the full report to further understand ACE’s current views and reasoning about the effectiveness of leafleting.

For instance, interviews of animal advocates with experience leafleting and reasoning about the comparative advantages of different farmed animal advocacy interventions both support this conclusion. See Part Five and Part Three of the report, respectively, for further discussion of what these sources of information can tell us about the effectiveness of leafleting.

Report

The organization of this report may differ slightly from the one described in our intervention evaluation guide, as the two projects were developed concurrently.

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Report

- Part One: Intervention description and a brief outline of a theory of change

- Part Two: Evidence from particularly relevant field randomized controlled trials

- Part Three: Some reasoning about the effectiveness of leaflets as an animal advocacy intervention

- Part Four: Case study analysis / Cost-effectiveness estimate

- Part Five: Interviews in the field

- Conclusions

Part One: Intervention description and a brief outline of a theory of change

The animal advocacy intervention of leafleting is a form of individual outreach. It is primarily carried out on college campuses, but to an extent it is also done at concerts and other large social events where the attendees are either teenagers or young adults, and/or liberal/progressive leaning.1 Leafleters usually say a short sentence2 while offering leaflets3 to many of the people who pass by. Leaflets are usually 5–20 page printed documents that attempt to persuade individuals to avoid or reduce animal product consumption.4 Leafleters can be paid staff of one of various animal advocacy organizations, or they can be volunteers. Leafleting is a common animal advocacy intervention used by various organizations, and several million animal advocacy leaflets are reportedly handed out in the U.S. annually. We would guess that most animal advocacy leaflets handed out in the U.S. are designed, printed, and handed out by Vegan Outreach. In 2015, Vegan Outreach reported distributing almost 3 million leaflets each year, most of which were handed out on college campuses.5, 6

This intervention report focuses on the effectiveness of these typical animal advocacy leaflets7 when claimed best practice approaches8 to leafleting are used. This means that this intervention evaluation does not directly consider the effectiveness of leaflets that only focus on quite specific aspects of animal advocacy such as limiting dairy consumption or chicken consumption, nor does it directly address leaflets that only focus on antispeciesism or wild animal suffering.

The following table offers a very brief theory of change for typical animal advocacy leaflets in the short to medium term.

| Some of the more likely possible outcomes in the short term9 |

|

|---|---|

| Some of the more likely possible outcomes in the medium term10 |

|

Part Two: Evidence from particularly relevant field randomized controlled trials

Methods and outcomes of literature search

Before completing this intervention report, we already knew of multiple studies from the animal advocacy community pertaining to the effectiveness of typical animal advocacy leafleting. This knowledge came from the general research we had completed over the past few years, as well as from conversations we had with leaders in the field. While completing the research required for this report, we became aware of some other evidence and research through a moderate literature search on Google Scholar in mid-late June 2017.12 Numerous pieces of identified evidence were excluded from further analysis because we thought that the interventions that they provided information about were different enough from those we studied that the interpretation of these results wouldn’t lead to meaningful updates about the effects of typical animal advocacy leafleting.13 Furthermore, including results produced by significantly different interventions in our leafleting meta-analysis could meaningfully distort our estimate of the effects of leafleting. In addition, one study conducted by two collaborating organizations was reported twice, once by each organization.14 A proposal for further study was identified that, as far as we know, isn’t going to be implemented in the near future.15 We also know of some relevant forthcoming studies that could further inform our views about the effectiveness of leafleting.16

An overview of particularly relevant field randomized controlled trials

Table 2 provides an initial overview of particularly relevant field randomized controlled trials. View the spreadsheet summary of findings.

Table 2 includes key information about aspects such as sample size, question wording, and food groups included in the assessment of animal product consumption, as well as sample characteristics. Before assessing the results of these studies we will first quickly assess the risk of potential biases in the studies. We didn’t commit ahead of time as to how this review would assess or deal with bias17 and the project leader wasn’t blinded to the authors or the institutions associated when assessing the risk of bias in these studies.18 It is important to assess the risk of bias in studies because it is a threat to their internal19 and external validity.20 Less biased studies are more likely to yield results that are closer to the truth and more biased studies are less likely to yield results that are closer to the truth. At times it was difficult for us to assess the risk of bias associated with studies because of the suboptimal amount of relevant information provided by the reports.21 Still, enough information was available that useful bias assessments could be completed. To perform these assessments, we used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, which involves assessing studies’ risk of being affected by six categories of bias: (i) selection bias,22 (ii) performance bias,23 (iii) detection bias,24 (iv) attrition bias,25 (v) reporting bias,26 and a catch-all item called “other sources of bias.” The presence of any of the first five items in a randomized trial has been found to often bias the resulting estimates of an intervention’s effectiveness.27 The bias assessments in each of those domains for the individual studies we analyzed, along with brief justifications, are available here. A summary of the bias assessments is presented in Table 4 and information for interpreting Table 4 is shown in Table 3.

| Symbol | Interpretation in terms of risk of bias28, 29 |

|---|---|

| Low risk of bias (i.e., plausible level of bias unlikely to seriously alter the results.) | |

| Unclear risk of bias (i.e., plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results) | |

| High risk of bias (i.e., plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results) |

| Study | Selection Bias | Performance Bias | Detection Bias | Attrition Bias | Reporting Bias | Other Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humane League Labs (2014) What elements make a vegetarian leaflet more effective? |

||||||

| Animal Charity Evaluators (2013) 2013 ACE Leafleting Study |

||||||

| Humane League Labs (2015) Which request creates the most diet change? |

||||||

| Hennessy (2016) The Impact of Information on Animal Product Consumption |

||||||

| Flens et al (2017) The Effectiveness of Leafleting on Reducing the Consumption of Animal Products in Dutch Students |

||||||

| Animal Equality Spain (2014) |

As can be seen in Table 4, each of the studies was judged to have at least one domain in which there was a risk of bias substantial enough that our confidence in its results is very limited.

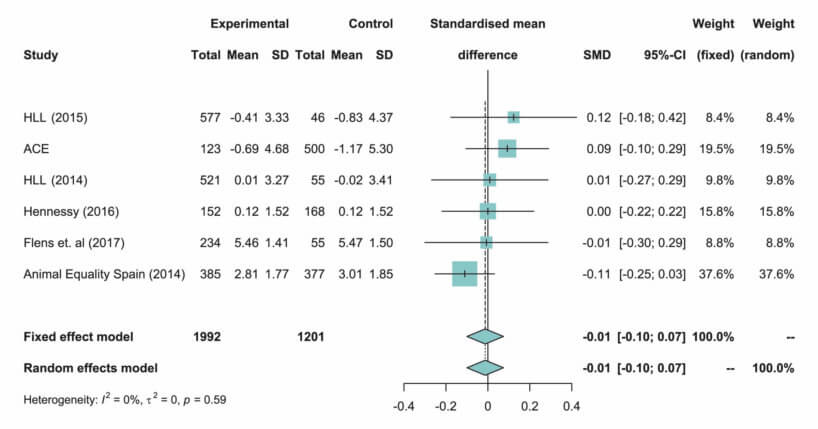

A meta-analysis of the six particularly relevant field randomized controlled trials

The data for this meta-analysis was extracted from the raw data of the six particularly relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) by the project leader.30 All else equal, pooling results of studies is likely to increase the precision of the estimate of the effect being studied (i.e., pooling results seems likely to narrow confidence intervals), and results with higher precision can better guide advocacy. Meta-analysis techniques involve pooling results by weighing studies according to the amount of information they contribute (more specifically, by the inverse variances of their effect estimates). This gives studies with greater statistical power more weight in the aggregated estimate, though it doesn’t account for the possible different biases and the extent of these biases in the results of each study.

In this meta-analysis, missing data from participants was ignored. Some measures were in interval censored form, providing information that an individual’s consumption of a product was within a given range of values, but not specifying a precise level of consumption. These variables were transformed to continuous outcomes by an algorithm which equally extended adjacent intervals such that there were no gaps between them and then computed the midpoint of the extended intervals to estimate the average value of that interval.31, 32 Other ordinal measures were treated as interval measures,33 and the clustering of participants was ignored.34 The meta package in R was used to create the below forest plots; the R code for generating the forest plots or for the extraction of data from individual studies is available upon request. There were also a number of specific data-aggregation decisions that were relevant to the interpretation of individual studies.35

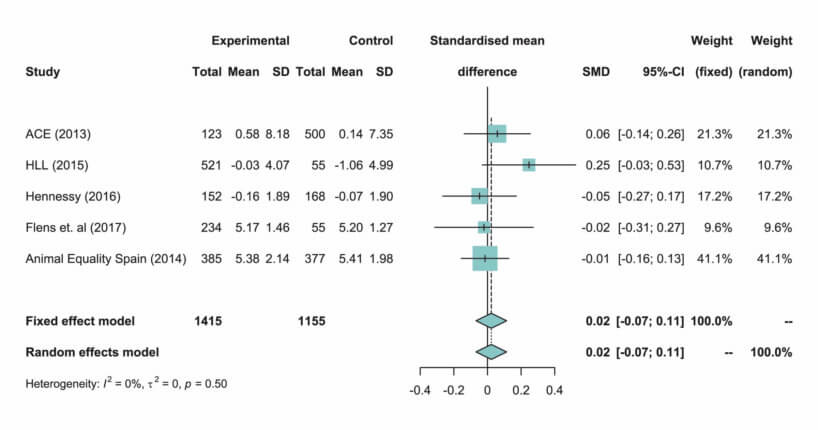

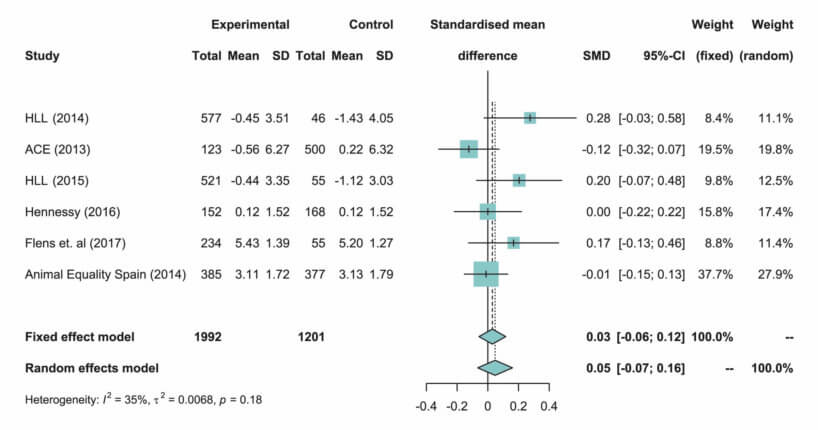

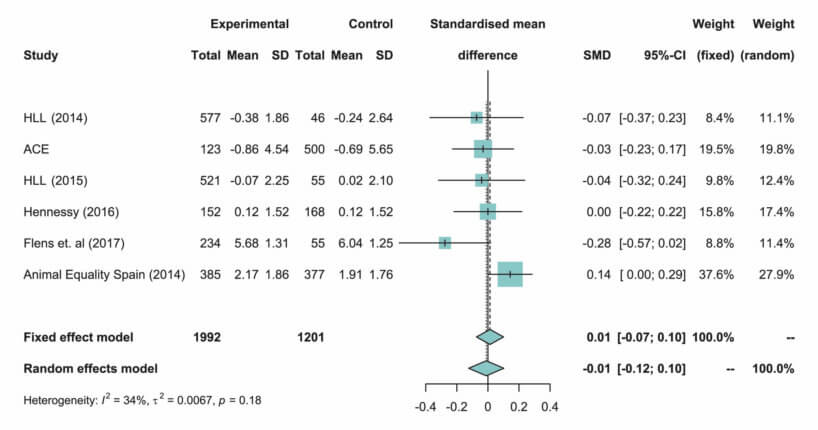

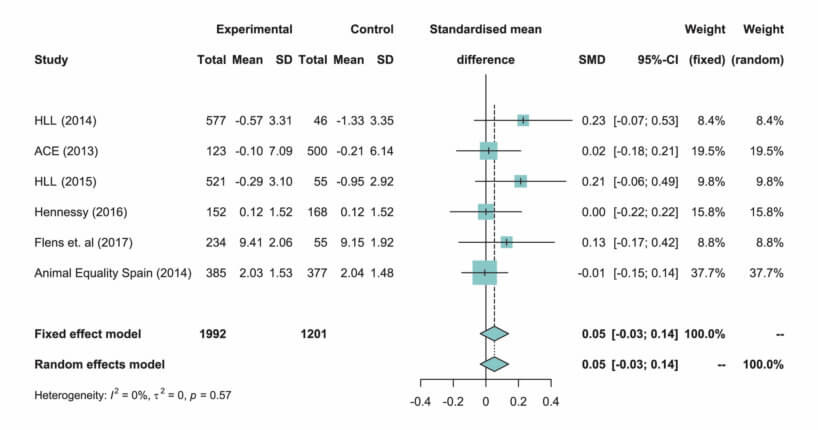

Most of the below forest plots show confidence intervals for Hedges’ g estimates of the standardized difference between the control group and the treatment group’s mean self-reported consumption of dairy, poultry, red meat, eggs, and fish. Standardized differences in means are used when studies do not yield directly comparable data, such as when studies assess the same outcome36 with different measures.37 Hedges’ g calculates the difference between the experimental and control groups, divided by the pooled standard deviation of these groups. Since in this case the standard deviations are generally about the same as mean consumption, thinking of our standardized mean differences (SMDs) as being roughly equal to the percent difference between the control and treatment groups’ means gives a general sense of the magnitude of the estimated effects. The endpoints of the lines for each study in the below forest plots indicate the 95% confidence intervals of the standardized effect estimate, which estimates the difference in animal product consumption between leaflet recipients and control group members—we would expect a negative effect estimate if leaflets are associated with reduced consumption of a given animal product, and a positive effect estimate if they are associated with increased consumption. The statistical power of each study is indicated by the size of the box around the point estimate of the effect size; bigger boxes correspond to studies with greater power, whose results are more meaningful and hence are weighted more heavily in the meta analysis. The diamond summary estimates (fixed effects model and random effects model) aggregate the results from the individual trials into an estimate and 95% confidence interval by accounting for both the differing estimated effect sizes and the differing statistical power of the experiments.

| Animal Product | Estimated standardized mean difference from meta-analysis as 95% CI (fixed effects model) | Estimated standardized mean difference from meta-analysis as 95% CI (random effects model) |

|---|---|---|

| Red meat41 | [-0.03, 0.14]42 | [-0.03, 0.14]43 |

| Poultry44 | [-0.06, 0.12] | [-0.07, 0.16] |

| Fish45 | [-0.10, 0.07] | [-0.12, 0.10] |

| Eggs | [-0.10, 0.07] | [-0.10, 0.07] |

| Dairy | [-0.07, 0.11] | [-0.07, 0.11] |

The fixed effects model is based on the assumption that the differences between the studies’ findings are due to sampling error.46 In contrast, the random effects model allows for the possibility that the true effect size differs from study to study in part because of real differences in the effect of the treatment in different circumstances, also known as study heterogeneity.47, 48 Our understanding is that there is no consensus on which model is preferable to use, but there is some evidence that fixed effects models overestimate confidence in treatment effects more than random effects models do, and that at least some Researchers believe there are only very limited circumstances in which a fixed-effects model is appropriate.49 Since there were potentially-significant differences in the circumstances and methodology of these studies, we will refer to the random effects model estimate when considering the results of this meta-analysis.

One noticeable result from this meta-analysis is that the 95% confidence interval for all the summary estimates overlaps with a point estimate of an effect size of zero. By following the conventionally applied frequentist framework of statistical inference, we would fail to reject the null hypothesis in all cases, and so would not reject the hypotheses that leaflets have no impact on consumption of any of these particular animal products. Another noticeable result from this meta-analysis is that in most cases the summary estimate is positive, suggesting that leaflets are more likely to cause increases in animal product consumption than decreases in animal product consumption. That is, in most cases it seems that the majority of the probability density function for the estimated effect of leaflets on animal product consumption suggests that leaflets cause increases in animal product consumption. This is the case for dairy, poultry, and red meat in both the fixed-effects and random-effects models, as well as for fish in the fixed-effects model, though (as mentioned above) the estimate is imprecise in all cases, and all of our results are consistent with leaflets having no effect on consumption.

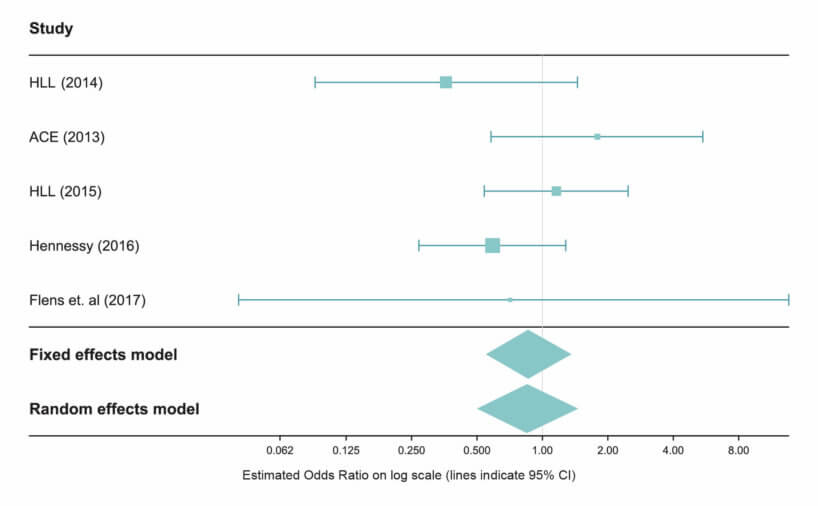

The following forest plot shows confidence intervals for the effect size estimate on lacto-vegetarian50 prevalence. For binary outcomes, effect sizes are often expressed as an odds ratio. In this case, the odds ratio represents the odds an individual in the treatment group would report a lacto-vegetarian diet divided by the odds that a participant in the control group would report a lacto-vegetarian diet. An odds ratio significantly greater than one indicates that, relative to assignment to the control group, assignment to the treatment group increases the probability of a participant reporting a lacto-vegetarian diet.

| Model | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| HLL (2014) | 0.36 | 0.09-1.45 |

| ACE (2013) | 1.79 | 0.59-5.47 |

| HLL (2015) | 1.16 | 0.54-2.48 |

| Hennessy (2016) | 0.59 | 0.27-1.29 |

| Flens et al (2017) | 0.71 | 0.04-13.6 |

| Fixed Effects Model | 0.86 | 0.55-1.36 |

| Random Effects Model | 0.85 | 0.50-1.46 |

Again, one noticeable result from the meta-analyses pertaining to lacto-vegetarian prevalence is that the 95% confidence interval for all the summary estimates overlaps with a point estimate of an effect size of zero.53 By following the conventionally applied frequentist framework of statistical inference, we would fail to reject the null hypothesis in all cases, and so would not reject the hypothesis that leaflets have no impact on lacto-vegetarian prevalence. Another noticeable result from this meta-analysis that the summary estimate suggests that leaflets seem more likely to cause decreases in lacto-vegetarian prevalence than increases in lacto-vegetarian prevalence. That is, it seems that the majority of the probability density function for the estimated effect of leaflets on lacto-vegetarian prevalence suggests that leaflets cause decreases in lacto-vegetarian prevalence.

Differences in the estimate of the effect of leafleting on different animal products and/or lacto-vegetarian prevalence seem to be too uncertain and not large enough to be worth discussing in detail. Given the high risk of bias in all the studies included in this meta-analysis, we think it is likely that the summary estimate 95% confidence intervals are not accurate 95% confidence intervals. There is some evidence that trials at high risk of bias tend to overestimate treatment effects (Moher et. al, 2010, Schulz 1995b, Odgaard-Jensen 2010) and we would guess that a similar conclusion would hold for the present meta-analysis but are somewhat uncertain about it. Several severe limitations to the available particularly relevant randomized controlled trials—including the limited scope of effects studied, the risk of several forms of bias, and possible variations in how intervention was carried out—further contribute to our uncertainty about these summary estimates. Furthermore, these confidence intervals don’t take into account our uncertainty in model selection during the meta-analysis and our uncertainty about which trials to include in the meta-analysis. As frequentist-style confidence intervals, these intervals don’t use Bayesian reasoning that incorporates our prior thoughts on the effectiveness of leafleting, which intervals representing our current beliefs on the subject arguably ought to do.54 For all these reasons, we treat these confidence intervals as very tentative estimates that need to be further updated to better estimate the effect of leaflets. (We estimate leaflets’ cost-effectiveness, and adjust for some external concerns, in Part Four of this report.) Despite our uncertainty, we do think that these estimates give relatively good information about the order of magnitude of the effect we should expect.

Some further elaboration on the limitations to the evidence from the particularly relevant field randomized controlled trials

There are numerous further limitations to the available evidence from the particularly relevant randomized controlled field trials apart from the previously mentioned risks of bias. The main additional limitations seem to be:

- The possibility of publication bias

- Possibly important differences in the way in which the intervention was implemented in the trials and the way in which it is usually implemented by animal advocacy organizations

- The evidence from the field trials still allows for significant uncertainty regarding the effect of leaflets on a variety of important outcomes (e.g., welfare reforms, ballot measures, demand for cultured animal products, and demand for animal products sourced through higher welfare methods)

We now briefly discuss each of these points in turn.

The set of available field trials may be constrained by publication bias among the groups who conduct such trials, which would make results that indicate that leaflets decrease animal product consumption more likely to be published than results that indicate that leaflets have no effect on, or cause increases in, animal product consumption. For instance, Animal Equality’s Spain and U.K. studies’ results have only recently been made public, several years after the experiments were performed. We would speculate that these delays in dissemination are at least in part because the results of the trials didn’t indicate that leaflets caused a significant decrease in animal product consumption (a result that the organizations involved had at least some incentive to demonstrate), and note there is some empirical evidence of a similar phenomenon in other fields (Guyatt et al, 2011). We know of at least some cases in which an organization chose not to formally analyze results from a leafleting study, though these may have been due to low response rates and hence low sample sizes rather than low effect sizes.55 There are also certain characteristics of leafleting trials that seem to increase the risk of publication bias. For instance, all of the studies are small in scale and appear to have been funded by the leafleting “industry”—i.e., by organizations that carry out or support leafleting. Meta-analyses that exclude unpublished results are at risk of overestimating intervention effects (Higgins & Green, 2011). ACE research staff think it is unlikely that other randomized controlled field trials of leafleting exist—this is because, due to our contacts at most animal advocacy organizations that conduct research, it is likely that we would know of these trials if they did exist.56 Still, it is possible that some trials were excluded because of a publication bias. If that were true, it would seem to make it more likely that this meta-analysis overestimates the possibility that leaflets cause a decrease in animal product consumption.

There may be a number of important ways that the manner in which the leafleting was performed in these highly relevant randomized controlled field trials differs from the way in which animal advocacy leafleting is usually performed. For instance, the leafleting in studies may be different than leafleting implemented by some large animal advocacy organizations, because these organizations often attempt to leaflet approximately 10% or 15% of a campus,57 while the studies we consider in the meta-analysis may have aimed to reach a different proportion—more likely a smaller proportion—of students on campus. The leafleters involved with the studies may also be less experienced than those who usually leaflet in the field. They may also give different instructions to recipients than they normally would.58 It is also possible that the leaflets themselves were meaningfully different in some way from the leaflets that are usually used in the field.59 Differences in how well leafleting was received in different areas could also impact studies that are trying to generalize about the absolute efficacy of leafleting.

There are also a number of important outcomes that these trials don’t measure. For instance, the trials don’t measure outcomes such as support for various actions that are likely to help animals, including welfare reforms, ballot measures, demand for cultured animal products, and demand for animal products sourced through higher welfare methods. There is also the possibility that leaflet recipients could share leaflets with people who weren’t included in the study and those people may have changed their behavior. Furthermore, the self-reported consumption measures used in these trials may meaningfully differ from actual consumption.60 More fundamentally, the outcome of interest is actually the change in the number of animals supplied through industrial agriculture rather than the change in the number of animals demanded.61 (Though even that change in supply may importantly differ from morally desirable outcomes.)62 Anecdotally, several major figures in the animal advocacy movement were reportedly converted by leaflets,63 which—if true—suggests leafleting may have important effects on building the animal advocacy movement. There are also some possible positive effects of leaflets on movement building, and perhaps some examples of leaflets being directly associated with large-scale outcomes that seem quite positive.64 The particularly relevant randomized controlled field trials also don’t account for how the effects of other interventions may impact the effectiveness of leafleting.65, 66 Given the lack of significant decreases in short-term animal product consumption detected by the meta-analysis, we lower our estimate of the likelihood that leaflets cause significant changes in recipients’ opinions or dietary behaviors.

Summary

Our analysis of evidence from animal advocacy had a number of Researcher degrees of freedom67 and was completed in a limited amount of time.68 When applicable, high-power and high-quality randomized controlled trials provide the most reliable evidence on the effect of animal advocacy interventions. However, in this case all of these trials were judged to be at high risk of at least one type of bias, and we would guess that this means that they are probably more likely to overestimate the decrease in animal product consumption caused by leaflets than to underestimate that effect (Moher et. al, 2010, Schulz 1995b, Odgaard-Jensen 2010). There is a risk that the overall evidence body is tainted by a publication bias, which again seems more likely to lead to overestimating the effects of leaflets, since a majority of these studies were conducted by organizations engaged in leafleting. There are also issues with the implementation of leaflets in the trials likely being at least slightly different from usual practice. Lastly, the results of the trials simply do not speak to the effects of leaflets on a number of important outcomes.

Overall, we have very little confidence in the point estimate of leaflets’ effect on consumption of various animal products. The estimated effects seem very likely to be somewhat inaccurate, possibly in a way that significantly affects their implications for our position on leaflets.69 Most of the potential biases in our data, such as publication bias across leafleting analyses published by animal advocacy organizations, seem more likely to lead us to underestimate than to overestimate the change in animal product consumption associated with leaflets. Thus, the lower bounds of our confidence intervals, corresponding to bounds on the amount by which leaflets might correlate with a decrease in animal product consumption, seem more likely to provide a reasonable bound on the effect size than the upper bounds. If the body of data we are using is indeed biased toward leaflets, it seems likely that there will actually be a greater than 2.5% chance that the true effect increases consumption by more than the upper bound of our 95% confidence interval. With the available evidence, we certainly can’t reject the null hypothesis that leaflets have no effect on short-term consumption of animal products. If anything, our meta-analysis of the available evidence instead causes us to update towards thinking that leaflets may actually cause short-term increases in animal product consumption rather than decreases. For those reasons we think that, as a body, the available evidence from particularly relevant randomized controlled trials seems to very poorly (if at all) support the case for allocation of resources towards leafleting, either in absolute terms or when it is compared to other promising farmed animal advocacy interventions.

| Poor | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

|---|---|---|---|

| There is little to no evidence to support this choice of intervention. Or, the evidence suggests an intervention may have no effect or a negative impact. | There is weak evidence to support this intervention but it is either exploratory in nature, weak in effect, or the studies are of low quality. | There is moderate evidence to suggest this choice of intervention. | There is strong, high quality evidence to support this choice of intervention. |

Part Three: Some reasoning about the effectiveness of leaflets as an animal advocacy intervention70

To aid in our evaluation of leafleting, we now very briefly examine:

- Possible places where leafleting has a comparative advantage over other animal advocacy interventions

- Some relevant social movement evidence

- Some possible macro indicators of leaflet effectiveness

- The effectiveness of individual outreach interventions in other areas which seem analogous to leafleting

- Some speculative reasoning about the long-term effects of leafleting

Possible places where leafleting has a comparative advantage over other animal advocacy interventions

Leafleting compares moderately favorably to other animal advocacy interventions in ease of scaling, as each additional leaflet is relatively cheap71 and large numbers of leaflets can be distributed by volunteers with little or no training. The fact that little or no training is involved with distributing leaflets also means that distributing leaflets provides a way for interested individuals to easily become more involved in animal advocacy.72 It seems clear that spending on leafleting results in relatively large numbers of people being exposed to farmed animal advocacy, and that favorable dietary change on their part may well result, in expectation, in a large benefit for farmed animals. However, we are very uncertain about not only the extent to which dietary change occurs due to leaflets, but, increasingly, whether the short-term diet changes associated with leaflets are in fact positive.

Leaflets have some potential advantages over online ads: they are a physical piece of literature recipients can keep and show others; the leafleter interacts with the recipient and there is the opportunity for a meaningful conversation; people often see dozens of online ads daily but are rarely handed a leaflet. However, if leaflets do have a significant favorable effect on short-term diet changes, then it seems that there is reason to expect that online ads would be more cost-effective than leaflets. This is because the mechanism for change behind the two interventions is very similar (i.e., short exposure to persuasive informational content) and online ads do seem to have a variety of meaningful advantages over leaflets. As Cooney (2014) notes, online ads can more narrowly target demographics (e.g., age, gender, interests) that are most receptive to animal advocacy messaging, and they require fewer financial resources. Online ad campaigns also appear to require less volunteer time than leafleting, so if organizations switched from leafleting to online ads, their volunteers’ time might be able to be used on other activities. Another possible comparative advantage is that if the ad provider’s payment method is per click on the online ads, then the advertiser will usually only pay for clicks from those who have an interest in the content, as opposed to paying to give leaflets to a substantial number of people who don’t seem likely to be affected by them. Online ad campaigns can yield a large amount of data, which is now often available through sources like Google Analytics and Facebook Insights; advocates can use this large volume of feedback to better refine their efforts.73 In addition, the cost per impression for online ads is substantially cheaper than that for leaflets, to the extent that, unless a leafleting impression is several orders of magnitude more effective than an online ad impression, it seems likely that online ads are more cost-effective.74 We would also guess that the short-term effects of undercover investigations may be more promising than leafleting because of the weak correlational evidence suggesting that negative media coverage is associated with a decrease in animal product consumption.

Our limited impression is that leaflets don’t seem to compare very favorably in a number of important areas when compared to other promising farmed animal advocacy interventions. In short, however, we are still quite uncertain about this. It appears that in many important areas, there is another promising farmed animal advocacy intervention that is likely preferable to leafleting. For instance, as previously mentioned, if leaflets do have a significant favorable effect on short-term diet changes, then it seems that there is reason to think that online ads would be more cost-effective than leaflets. Based on the available evidence from the particularly relevant RCTs, the effects of leafleting that are more easily measurable don’t seem as promising as those effects of corporate outreach that are easily measurable. We would guess that leaflets have weaker effects on building the animal advocacy movement and increasing the likelihood of a major social shift away from factory farming than either (i) interventions featuring more in-depth materials, such as documentaries and books sympathetic to animal advocacy, or (ii) interventions more directly attempting to increase consumer acceptance of cell-cultured or plant-based animal product substitutes.

Some relevant social movement evidence

Given the time constraints involved with this intervention report, we only briefly examined some of the social movement evidence pertaining to leafleting, and we think that it has notable limitations.75

Leaflets could be broadly categorized as an individual consumer-action approach to causing social change. Critics argue that such approaches are not supported by historical examples or other empirical evidence.76, 77 It appears that promoting the individual consumer approach of recycling was successful,78 but this was carried out in large proportion by beverage corporations (Elmore, 2012), making the analogy to animal advocacy leafleting tenuous. We are also aware of some limited evidence of the use of leaflets in other social movements, such as the women’s rights, slavery abolition, and children’s rights movements.79 However, we are unaware of any detailed analysis of the role that leaflets played in those movements. For this reason, and because inferring causality from history is inherently difficult, it is unclear to us just how large a role leaflets have played in social movements where they have been employed. Our limited impression is that:

- Relevant Researchers generally don’t seem to think that leaflets played a large role in most social movements.80

- Leaflets have not been widely considered as an essential part in any other contemporary social movement’s recent work.

Some possible macro indicators of leaflet effectiveness

Another approach to evaluating the effectiveness of leaflets is through what GiveWell defines as “macro” evidence: “evidence from programs carried out on a large scale (regional, national, or multinational) without separating people into “treatment groups” and “control groups.”81 Leaflets and similar forms of outreach could have contributed to the current perception in the U.S. that farm animals are frequently mistreated for commercial gain,82 and/or they could have contributed to, or could be contributing to, the growing awareness of veganism.83 There are other interventions which may have had more of an effect—investigations, for example, which often achieve broad media coverage—but it is difficult to tease out causation from observation of social trends.84 There is also some reason to think that leaflets may have played an important part in building the animal welfare movement by generating publicity and attracting future movement leaders. However, that reasoning seems to suggest that investigations and influential books and/or documentaries played a larger role.85, 86 At one point in the animal advocacy movement’s history these individual outreach interventions may have been a good course of action, but it is now no longer clear whether these individual approaches are the optimal course of action. Indeed, a small survey of some effective animal advocacy Researchers seemed to indicate that there was a consensus favoring institutional approaches over individual approaches.87

One could check calculations of the vegetarian conversion rate of leaflets against a back-of-the-envelope calculation that uses estimates of:

- The proportion of vegetarians

- The average vegetarian adherence length

- The number of leaflets handed out annually

- The proportion of the vegetarians created by leafleting88

This doesn’t seem like a useful check for our cost-effectiveness estimates. This is because (i) we don’t focus on vegetarian conversions and (ii) we don’t have particularly good data for some of the important parameters in that calculation. Still, it is worth noting that even some quite preliminary models seem to relatively strongly conflict with high estimates of both vegetarian conversion (e.g., >5%) and adherence (e.g., >5 years) as a result of the leaflets. What may be more informative is looking at changes in vegetarianism and veganism rates in countries that Vegan Outreach (or other leafleting organizations) have recently expanded into, especially if they decide to leaflet there such that a relatively large amount of leafleting occurs per person. In this ideal location where non-leaflet efforts aren’t increased also, comparing the number of new vegetarians and vegans to the number of leaflets distributed could then give us an upper bound on the rate of diet conversions from leaflets.

The effectiveness of individual outreach interventions in other areas which seem analogous to leafleting

It may be possible to draw some lessons about the effects of leafleting from studies of increasing voter turnout. Perhaps the most studied behavior change that is reasonably similar to that asked for in animal advocacy leaflets is turning out to vote in U.S. elections. In a 2016 conversation with Josh Kalla, a PhD student in political science at University of California, Berkeley, we were told that a review of hundreds of experiments on different get out the vote (GOTV) tactics indicated that the more personal the communication, the larger the effect size. The review in question also estimates that one vote can be gathered per 189 leaflets handed out, and estimates that the cost per vote through direct mailings89 is $67 (Green & Gerber, 2004).90 However, there are significant differences between reduced animal product consumption and voting: “voting seems to be more widely agreed upon as the right thing to do than the agreement about the ethics of reducing animal product consumption, reduced animal product consumption is a sustained effort whereas voting is a one-time event, [and] there are more GOTV campaigns, so vegetarian ads may face lower-hanging fruit […] images of animals may or may not be more effective than GOTV reminders/arguments.”91 We are unsure if the GOTV reminders are part of the best reference class to use in forecasts concerning animal advocacy leaflet effectiveness. Since we have a limited idea of what the appropriate reference class is for forecasting the effectiveness of leaflets, and a limited idea of the outcomes for that reference class, the performance of this one analog alone currently does not result in a significant change in the performance we expect for leaflets.

Some speculative reasoning about the long-term effects of leafleting

It seems likely that the vast majority of animals whose lives we can affect will live in the far future. If we were certain about the long-term effects of interventions, this would probably be our primary consideration in deciding what to promote. However, although the far future is very important, we don’t have enough confidence in our predictions to base all our decisions on what we believe about it. There is extremely limited evidence available to suggest how leaflets may shift conditions for farmed animals over the very long term,92 and any long-term predictions about this seem highly uncertain.93 We aren’t aware of anyone who has attempted to study this subject explicitly, and there are few clear parallels to past situations in other movements.94 In the absence of strong evidence, multiple contradictory theories are possible regarding how leaflets could affect the situation for animals in the far future, and it seems that we have very little evidence available here beyond speculative reasoning.

Animal advocacy leafleting of the type considered in this report seems to have an incremental, consumer-change based approach to social change, which may or may not be desirable. This form of leafleting seems less focused on building a mass movement than some other animal advocacy interventions such as animal advocacy protests or legal reform initiatives—although that is a tentative conclusion. If effective, leaflets address both dietary and attitudinal change, but seem to focus to a greater extent on dietary change, and so may be more likely than other approaches to lead to immediate behavior change that directly spares animals. If people simply changed their attitudes with respect to farmed animals, that might not lead to actual impact for animals. After all, many people currently care about animals, but relatively few are vegetarian or vegan.95 It might actually be easier to change individuals’ diets without making a moral appeal (e.g., by promoting cultured meat). Acceptance of the moral arguments against meat eating may follow, rather than precede, diet change.

It is unclear what impacts, if any, leaflets have on the broader state of affairs for animal agriculture and how animals are viewed in society. We know of little, if any, historical precedent that shows major social change—perhaps roughly equivalent to a greater than 20% reduction in the number of animals raised for food—being caused by individual advocacy and/or changes in personal consumption. This means that, although leaflets might cause some more immediate changes in the demand for animal products, they might not have as much impact on animal welfare in the long run as other interventions. Such other interventions might include protests or legal reform, both of which have some historical precedents to provide evidence that they can lead to social change. In their focus on individual dietary change, typical animal advocacy leaflets tend to focus on vegetarianism or a reduction in consumption of animal products, rather than complete veganism. Some contest this approach, claiming it dilutes the message of animal advocates and makes it more difficult to convince people of the seriousness of animal suffering in the long run.96 We also recognize this concern, but we haven’t seen convincing evidence that these undesirable effects clearly outweigh the potential benefits of reducetarian/vegetarian messaging, such as a lower barrier to entry for the animal advocacy movement that could increase total support and momentum. Critics also believe it is difficult to build a mass movement when the perceived criteria for acceptance in the movement is a lifestyle change. Additionally, they believe that a consumer focus provokes less moral outrage than focusing on the institution of factory farming—and that therefore this approach is missing an important driver of activism and subsequent social change.97 Those beliefs don’t seem clearly unreasonable, but they don’t seem to be strongly supported by evidence. Even within that framework, leafleting could still function as an effective complement to other interventions.98

Overall, we do not think most organizations engaging in leafleting view it as part of a coherent strategy to provide benefits to animals in the far future. Its long-term effects are not well understood, and could be either positive or negative. As with most interventions performed by animal advocates, we think the long-term effects are more likely to be positive than negative, because promoting concern for animals’ interests is so important that in the absence of strong reasons to believe the effects are negative, we think it is likely that the effects are positive on balance. We don’t think the long-term effects of any animal advocacy intervention are extremely well understood—though some seem clearer than the long-term effects of leaflets—and so we put limited weight on this consideration in our overall understanding of how effective or ineffective any intervention is.99

Summary

The comparative advantages that leafleting has over a number of other farmed animal advocacy interventions mainly seem to be its (i) ease of scaling, (ii) lower bar for involvement of newer advocates who lack experience and/or training, and (iii) the large number of leaflet recipients exposed to animal advocacy. The available historical/social movement evidence doesn’t seem to either strongly support the use of leaflets or to strongly weaken the case for leafleting being a highly effective animal advocacy intervention. The available “macro” evidence is rather inconclusive, but does seem to make it unlikely that leafleting has a high rate of converting people to vegetarian diets which they adhere to for multiple years. We also have a limited idea of what the appropriate reference class for forecasting the effectiveness of leaflets is and what the outcomes for that reference class would be; as a result, currently the results of interventions we consider to be in this reference class don’t play a large role in our reasoning. Finally, there is extremely limited evidence available to suggest how leaflets may shift conditions for farmed animals over the very long term. Still, our tentative conclusion is that the comparative advantages of leafleting seem to be outweighed by the disadvantages, when compared to promising farmed animal advocacy interventions. Important considerations include short-term diet effects, short-term effects on farmed animal welfare, contributions to movement building, and plausible long-term effects; in each of these areas, we have reason to think that another intervention outperforms leafleting. In short, our limited impression is that qualitative concerns do not generally favor leafleting, and in some areas indicate that other interventions may be preferable.

| Poor | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

|---|---|---|---|

| Little is understood about the effectiveness of this intervention. | There is some understanding of the effectiveness of this intervention, weakly supported by evidence. | There is a good understanding of the effectiveness of this intervention, moderately supported by evidence. | There is a strong understanding of the effectiveness of this intervention, tested and supported by evidence. |

Part Four: Case study analysis/Cost-effectiveness estimate

Case Study Analysis

Case Study Analysis of The Humane League Site Visit 2015: San Diego Warped Tour

The original notes on this case study were written by Jon Bockman, ACE’s Executive Director. The Humane League’s San Diego grassroots Director, Beau Broughton, seems to have been the primary organizer for the leafleting event that Jon observed. The event involved Humane League staff, interns, and volunteers handing out leaflets at the Warped Tour music festival. This event was originally selected for a case study by Bockman in order to observe THL’s operations, rather than to observe a representative leafleting event.

The leafleting at this event seemed well organized: leafleters appeared professional, they were well received (in that no negative reactions were recorded), they were able to connect their message100 to the vegetarianism of some band members, and they were leafleting a receptive demographic (14–20 year-olds with some interest in ideas or culture outside the mainstream).101 This case study seems to present a successful example of leafleting at an event where many passersby would be of a targeted demographic.

Bockman noted that the take rate of the leaflets was very high, with around 90% of the people offered a leafleting accepting it. This provided some further evidence that the leafleting was well executed. A likely explanation for this high take rate was the successful targeting of a quite suitable demographic. Additionally, Bockman thought that the leafleters were given reasonable, standard advice before the leafleting commenced.102

Of the eight leafleters, five were staff or interns, and three were volunteers (including Bockman). This meant that it was mostly staff time being spent on the intervention. However, Broughton mentioned that the number of volunteers is variable—he gave an example of a time when there were 15 volunteers and five staff members at an event.

The group of ten leafleters distributed an estimated 7,383 leaflets in two hours. This is over twice the rate at which leaflets were handed out in our second case study. Broughton said that looking at how many leaflets are discarded is more trouble than it’s worth as a method of trying to assess how effective the leafleting was.

No one who received a leaflet came back to talk to Bockman. Bockman thought that this was probably because they were on their way out of the event at this time, and so would not naturally have walked by the leafleters a second time.

Bockman also did not report any conversations he had with the audience, other than some mentioning that they had received many of these leaflets before. Jon thought these people were a small minority and had probably received these leaflets before because they had come to the Warped Tour before. This was the only evidence of possible audience saturation in any of the three case studies.

This leafleting event seemed to be the most well-organized of the three described case studies in this report.

Case Study Analysis of The Humane League Site Visit 2015: Leafleting and Meeting with Board Members

The original notes on this case study were by Allison Smith, ACE’s Director of Research. Rachel Black, then the Humane League’s Philadelphia Director, was the primary organizer for the event. The event involved a Humane League staff member, two interns, and a volunteer handing out leaflets outside the library at the Community College of Philadelphia. This event was originally selected for a case study by Smith in order to observe THL’s operations, rather than to observe a representative leafleting event.

At this event, Smith observed that the leaflets were handed out quite quickly (846 per hour by the four leafleters, by her count). Black was very impressed by the take rate and noted that she would have been only 100 leaflets short of meeting her goal for the entire semester after this event. Only one of 40 people Smith observed discarded their leaflet.

Black considered cancelling the leafleting event because it was raining, and she had to adapt her plans in order to go forward with the event. She leafleted in a less familiar area because of this. The leafleters expected that the event would have gone better (including attracting more volunteers) if it had not been raining. Some of the audience had conversations with Black, but Smith did not hear what was said in them.

This case study provides a similar level of evidence as the previous case study, though the previous case study seemed to provide a greater level of detail.

Case Study Analysis of Moving Mountains: Animal Rights Organizations, Emotion, and the Autodidactic Frame Alignment, Appendix C: Observation Report

The original notes on this case study (p.146–149) were taken by Lee Jarvis as part of a dissertation on the use of emotional messaging in the animal advocacy movement. Jarvis only refers to the leafleters as volunteers and it isn’t clear to us which individual organized the event, but the organization involved was Vegan Outreach. The event took place on a commercial street in Miami Beach, Florida.

In addition to the leafleting component of this event, the volunteers were using a video to attempt to motivate people to reduce their animal product consumption and they also had a table where some further resources were available. This means that it isn’t clear whether some of the observed evidence ought to be attributed to the leafleting or to the other facets of this event.103

Of the three case studies, this case study provides the most information about the psychological responses of the people who receive leaflets. Of the four people who Jarvis observed stopping and talking to the volunteers, two were vegetarian or vegan. The two others were large, athletic men who were concerned about staying healthy and fit on a vegan diet. That provides some very weak evidence that athletic men may be an underserved demographic. The volunteers at this event did seem to be prepared; they had some special leaflets geared towards athletes as well as a poster on their booth that catered to athletes.104 The fact that Vegan Outreach had these special leaflets and posters ready provide some evidence of their good judgement in the planning of this event. That this event took place near a beach may mean that athletic men were overrepresented relative to the average leafleting audience. This event seemed to be less well targeted at what seem likely to be the demographics most receptive to leaflets, relative to the other two case studies.

Jarvis did observe that many of the audience appeared to be in their 20s, but we would guess they were possibly less concentrated in that demographic than the other two leafleting events, and they were probably less likely to be liberal or have some interest in ideas or culture outside the mainstream. These factors may have been responsible for the lower take rate at this event; around half of those offered a leaflet took one. One of the volunteers at this event suggested to Jarvis that for one night with a three-person booth, typically 2–10 people stop to talk to them or ask questions.105

This was the only one of the three case studies where any negative reactions were reported106 by the authors, though there were still very few negative reactions reported.

Summary of Case Studies

Case studies can provide valuable information about interventions. This could be particularly true for leafleting, given the lack of high-quality research investigating the intervention. The lack of negative reactions in these case studies could be seen as evidence of effectiveness, though it could also be attributed to a lack of engagement from the audience. The information about the different “take rates” across the case studies is suggestive of there perhaps being significant variance in this factor across leafleting events.107 The case studies also indicate that it is worth considering the audience of leafleting and tailoring messages to that audience where possible. Lastly, it is at least somewhat informative that the final case study mentioned that leafleters felt that people watching videos shouldn’t be interrupted, possibly suggesting that they think videos are more persuasive than a leaflet.

However, in order for these case studies to have provided moderate or strong evidence about the effectiveness of leafleting, evidence about the long-term behavior of those receiving leaflets would be needed. Some insight into the psychological state of those receiving leaflets might have given some evidence about this behavior change, but there was little opportunity in any of the case studies for positive or negative evidence about that. This is because not many conversations with the audience were recorded. No cost-effectiveness estimate was attempted for any of the three case studies because the amount of resources used in them was not clear, and the level of behavior change achieved was also not clear.

Of the 15 people in total who were leafleting at these events, eight were staff or interns, and seven were volunteers. Since one of the advantages that ACE sees in leafleting is relative ease of volunteer involvement, this perhaps low number of volunteers could be somewhat concerning. However, these case studies may not be representative of the ratio of staff and interns to volunteers at leafleting events in general. This is because the events at which Bockman and Smith completed case studies were specifically selected to observe THL’s operations, rather than to observe a representative leafleting event.

In sum, these three case studies provide poor or no evidence in favor of the proposition that leaflets are more cost-effective than other promising animal advocacy interventions.

| Poor | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development of case studies did not provide evidence to support this intervention choice. | The case studies provided weak evidence to support this intervention choice. | The case studies provided moderate evidence to support this intervention choice. | The case studies provides strong evidence to support this intervention choice. |

Cost-effectiveness estimate108

The limitations of our cost-effectiveness estimate

This cost-effectiveness estimate is an approximation of the costs and benefits of leafleting. It is highly uncertain, because the evidence pertaining to the effects of typical animal advocacy leaflets is at a high risk of bias and has other severe limitations. We worry that readers may think that we have a higher degree of confidence in this cost-effectiveness estimate than we actually do. To be clear, this is a very tentative cost-effectiveness estimate and it plays only a limited role in our overall opinions of which charities and interventions are most effective. We are more confident that the values of the bounds of the interval, and the corresponding confidence levels, represent reasonable estimates than we are that the average value of the estimate provides an accurate point estimate. However, we still feel uncomfortable putting too much weight on the bounds because they involve quantifying very difficult to quantify sources of uncertainty. There are also a number of parameters involved in this estimate that add additional uncertainty above and beyond that which we already had about the evidence from the particularly relevant quantitative trials. In some cases we have assigned quantitative values according to our best judgment and reasoning.

This cost-effectiveness estimate of leafleting is an approximation that does not take into account the possible positive or negative consequences of leaflets on a variety of outcomes. It only attempts to estimate the direct short-term effects of leaflets on the consumption of some animal products; all other possible effects of leaflets have been excluded. For instance, the possible effects of leaflets on shellfish consumption and wild fish consumption have not been included, nor have the possible indirect effects of leaflets on the short-term consumption of animal products (e.g., through possibly making other animal advocacy interventions more likely to succeed). This estimate also assumes that changes in consumption linearly correspond to changes in the self-reported number of meals containing a given animal product. In addition, it makes use of simple assumptions about the costs involved with leafleting by, for instance, not attempting to incorporate the opportunity costs for the volunteers involved. There could also be meaningful differences in moral status between different farmed animal species, and this model doesn’t attempt to account for them. Additionally, there are potentially meaningful differences in the average welfare of different species of farmed animals, and this model doesn’t attempt to account for that either. Again, this cost-effectiveness estimate is an approximation and it relies on flawed data and extremely difficult to quantify sources of uncertainty. Those severely suboptimal features contribute to the reasons why cost-effectiveness estimates are far from the only factor we consider when we evaluate interventions and charities. The following estimate should be interpreted carefully—it is a rough estimate, and not a precise calculation of cost effectiveness.

Reasoning behind our cost-effectiveness estimate

We are aware of a number of different estimates of the cost per leaflet distributed. For instance, a number of estimates suggest that it costs less than $0.10 per leaflet distributed,109 while others suggest that the cost per leaflet distributed is slightly more than $0.10.110 These estimates appear only to account for the cost of purchasing leaflets, and not for further costs involved with their distribution. To better approximate the cost per leaflet distributed, we will use information from a 2014 conversation with Jack Norris of Vegan Outreach, in which we were told that the estimated costs that Vegan Outreach pays when they print and hand out literature at colleges are between $0.25 and $0.50, depending on how far they have to travel. Similarly, in ACE’s 2016 review of Vegan Outreach, we estimated that the cost per leaflet distributed was $0.31 to $0.42. The marginal cost per leaflet may be much lower than this, but it is useful to consider the total costs of a leafleting program when evaluating the overall cost-effectiveness of an organization, and these overall numbers also help guide our thinking as to whether organizations should pursue leafleting at all. Even these total cost numbers have a large amount of uncertainty. We don’t feel highly confident in those estimates and would guess that it is not highly unlikely that they could be misleading by a factor of 3 or 4—but it seems highly unlikely that they are incorrect by an order of magnitude. To incorporate that uncertainty in our cost-effectiveness estimate, we will use a lognormal distribution with a 90% subjective confidence interval111 of $0.16–$1.60 per leaflet distributed for leafleting in general.

As for the change in animal products consumed per leaflet distributed, we will use the results of the meta-analysis for the six particularly relevant field randomized controlled trials as one key parameter in our initial model to estimate them. The estimated standardized differences in group means from the meta-analysis are shown in Table 5. As described in Part Two of this report, these differences were calculated by pooling the results of the particularly relevant field randomized controlled trials (with inverse variance weighting) and evaluating Hedges’ g of the pooled results. In order to convert those standardized mean difference estimates into estimates of change in animal product consumption, we first need to translate them back into one of the dietary change dependent variables used in some of the randomized controlled trials. We will translate the pooled estimates into consumption numbers using the meals-per-week results from the two HLL field trials. We chose these variables mainly because a greater number of respondents across the analyzed studies were asked to describe their consumption in this format. Our estimates of the effects of leafleting will take into account the reported consumption of all participants at baseline and the control participants at endline to calculate the mean of diet change under control conditions, as well as the standard deviation of consumption for all participants. This information allows us to estimate what difference in meals per week corresponds to the estimated standardized difference in means.112 We pooled the results from the HLL field trials for leafleting to give an estimate of the number of meals per week that the respondents reported consuming animal products (in a typical week), and to calculate the standard deviation of overall consumption. These values are shown in Table 7.

| Animal Product | Estimated standardized mean difference from meta-analysis as 95% CI (random effects model) | Mean number of meals containing this in a typical week (estimated standard deviation in parentheses) | Estimated standard error of the mean number of meals in a typical week containing this animal product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red meat113 | [-0.03, 0.14]114 | 4.38 (3.88) | 0.050 |

| Poultry115 | [-0.07, 0.16] | 5.91 (3.76) | 0.048 |

| Fish116 | [-0.12, 0.10] | 2.07 (2.57) | 0.033 |

| Eggs | [-0.10, 0.07] | 4.31 (3.52) | 0.045 |

| Dairy | [-0.07, 0.11] | 7.21 (4.41) | 0.083 |

Knowing this estimated mean and standard deviation in consumption, and the estimated standardized mean difference between the treatment and control groups’ consumption, we can then estimate the percentage increase in the number of meals associated with being in the treatment group. We then use that percentage increase to estimate the change in demand for farmed animal products. Using estimates of the cumulative elasticity factors for these products, we also estimate the corresponding change in supply per dollar spent on leafleting, both in terms of animals spared and years of animal suffering averted.117 We also have to estimate the duration of the change in consumption associated with leafleting. For specifics, please see the full model in Guesstimate.

Somewhat counterintuitively, this estimate—which, again, doesn’t take into account the possible indirect short-term effects and is based on a very limited evidence base—suggests that leaflets’ direct short-term effect is to increase farmed animal suffering. The result of the cost-effectiveness model is a 90% subjective confidence interval for the change in supply of farmed animals per dollar ranging from a decrease in supply of 0.3 animals to an increase in supply of 10 animals118 and a corresponding change in the number of years of farmed animal life of -0.4 to 1 years.119 Note that the probability distributions within these subjective confidence intervals are not symmetric; instead, they are positively or right skewed. A lot of the variation in these values, as well as the reason the ranges are more positive than negative, is due to the estimated effect of leaflets on broiler chicken consumption. That is, the main reason that the estimate is positive is because the estimated standardized mean difference from the meta-analysis was symmetrically distributed with most of its probability mass on leaflets causing an increase in poultry consumption. We didn’t complete a sensitivity analysis of the results from the meta-analysis. It is possible that slightly different assumptions would have caused the point estimate for the standardized mean difference for poultry to in fact be negative, and that could have have led to the point estimate for leaflets’ effect to be a decrease in farmed animals raised and farmed animal life-years rather than an increase.

We make subjective adjustments to this cost-effectiveness estimate to incorporate the following information:

- There is animal advocacy evidence from other randomized controlled field trials and randomized field trials that seem relevant. Upon initial inspection the results of some other relevant trials seem to be more positive,120 but the results from a randomized controlled field trial of online advertising are similarly negative.121

- Our general understanding of psychology and advertising makes us think that it is somewhat unlikely that leaflets will increase animal product consumption in the short term.122

- We would probably expect that the high risk of bias in the six particularly relevant field randomized controlled trials would lead to favorable overestimates of the effects of leaflets.

- The estimate is quite sensitive to small changes in the estimate of the effects of leaflets on broiler consumption and our uncertainty in model selection during the meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness estimate.123

In order to better agree with the first three factors, we believe that our cost-effectiveness estimate should account for a rough estimate of our Bayesian prior for the how effective leaflets are. We guess that our prior for the estimated SMD caused by leaflets is normally distributed with a mean of -0.005 and a standard deviation of 0.1.124 Note that we didn’t commit ahead of time to that Bayesian prior, and that it is based on rough subjective judgments.125 We will also attempt to incorporate a factor to account for general model uncertainty by slightly biasing our estimates of the SMDs upwards and multiplying their standard deviations by 1.75.126 This is an attempt to account for the possibility that different reasonable analytic decisions in the meta-analysis could have led to different results. Note that the value of the factor to account for general model uncertainty is based on our rough subjective judgement. These adjustments weren’t pre-committed to before our viewing the results of the meta-analysis and the resulting unadjusted cost-effectiveness estimate. It is possible that our reasoning for including these subjective adjustments was suboptimal, and we encourage readers to examine these subjective adjustments closely.

The results from the cost-effectiveness model initially were a 90% subjective confidence interval for the change in supply of farmed animals per dollar ranging from a decrease in supply of 0.5 animals to an increase in supply of 10 animals127 and a corresponding change in the number of years of farmed animal life of -0.2 to 1 years.128 With the above-mentioned subjective adjustments, our 90% confidence interval now becomes a decrease in supply of 3 to an increase in supply of 10 animals129 and a corresponding change of -2 to 2 farmed animal years per dollar spent on leafleting.130 Note that the probability distributions within these intervals are not symmetric; instead, they are positively or right skewed. Those who disagree with us about the subjective adjustments might want to consider only the original estimate, or possibly make their own subjective adjustments to that original estimate. Given the very high uncertainty involved in making this estimate, and the relatively small part that this estimate plays in our overall evaluations, we don’t think it is worth speculating further about the shape of our subjective probability distribution for the effect of leaflets on short-term consumption of some animal products.

| Poor | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development of cost-effectiveness estimate did not provide evidence to support this intervention choice. | The cost-effectiveness provided weak evidence to support this intervention choice. | The cost-effectiveness provided moderate evidence to support this intervention choice. | The cost-effectiveness provides strong evidence to support this intervention choice. |

Summary

The case studies we considered provided limited evidence about the effectiveness of leafleting, because they didn’t address whether there were changes in the short- or long-term behavior of those receiving leaflets. Our cost-effectiveness estimate didn’t incorporate information from any of the three case studies, because the amount of resources spent on each of those leafleting events was not clear—and, more importantly, the level of behavior change achieved through these events was not at all clear. This cost-effectiveness estimate appears to indicate that, compared to the short-term calculable effects of other animal advocacy interventions, leafleting is likely to be less cost-effective—and may even be actively counterproductive, at least in terms of these effects. Note that because this cost-effectiveness estimate is largely based on the meta-analysis completed earlier in the report, it shouldn’t be taken as separate or corroborating evidence of that meta-analysis. Still, it is worth reiterating that it is fairly concerning that for some animal products the cost-effectiveness estimate assigns less probability to short-term decreases in consumption than to to short-term increases in consumption. We believe that a qualitative analysis that considered the results of this cost-effectiveness estimate along with the variety of factors mentioned in Part Three of this report would moderately update us towards the conclusion that the effects of leaflets are positive in expectation. For instance, since leaflets seem a priori more likely than not to promote concern for farmed animals, they could complement other farmed animal advocacy interventions in ways that may accelerate and make the success of those other interventions more likely. Leaflets also appear to have played a non-trivial role in building the contemporary animal advocacy movement. Our impression is that if such qualitative effects of leaflets were incorporated into the cost-effectiveness estimate, then the impact of leaflets would be estimated to be positive in expectation.

Part Five: Interviews in the field

Matt Ball of One Step for Animals, Rachel Black of The Humane League, and Jon Camp of The Humane League were interviewed as part of this report.131

In their interviews, Ball and Camp both noted that in their experience many people responded to leaflets that asked for full veganism by stating that they “could never go vegan.” This contributed to both of them favoring requests to reduce animal product consumption. Ball and Camp noted that, over the past two decades, leaflets had moved from originally being something like an academic position statement, to now being an attempt to persuade people as effectively as possible with simple writing, pictures, and a more positive focus.

Black and Camp had similar views on a number of points relevant to leafleting. These included that:

- Communication and coordination between the main animal advocacy organizations that practice leafleting is very good.

- Experience is not very important for being good at leafleting; the personality of the leafleter is at least as important.

- Some colleges and universities were much more receptive to leafleting than others. Ball also mentioned differences in how well leafleting was received in different areas, and thought this could bias studies of local populations that were trying to generalize about the absolute efficacy of leafleting.

All of the interviewees had noticed that within the past decade or two leaflet recipients had become more familiar with the ideas presented in the leaflets and seemed to become more sympathetic to them. The extent to which leafleting is responsible for this change is unclear. Ball noted that although people were more receptive, total animal consumption in the United States had still increased. Ball thought that leafleting could potentially have a net-negative effect by encouraging people to substitute chicken for other animal products (therefore increasing the total number of animals subject to factory farming). Part of his reasoning for why this could occur was that the arguments made in leaflets for reducing animal product consumption seem to apply more—or even much more—strongly to red meat than to chicken.