Protests – 2018

Overview

Protests are a frequently used intervention in animal advocacy. We estimate that between 40 and 80 animal advocacy protests occur each week in the U.S. alone. Despite their prevalence, the purpose and effects of protests are poorly understood. One common misconception is that protests are intended to change public opinion; in fact, organizers often report that protests are intended to disrupt existing states of affairs in order to spur more systemic change.

Evaluating the effectiveness of protesting as an animal advocacy intervention is a complicated task, particularly because protests vary widely in implementation and context. Our report focuses on paradigmatic gatherings of activists that are disruptive1 and nonviolent, but even these comprise a heterogeneous group. Because there is little empirical research on the effects of protests in animal advocacy, we draw from research on the effects of protests in other social movements. Our conclusions are inevitably uncertain, as questions remain about whether or to what extent evidence from other social movements generalizes to the animal advocacy context.

Overall, we would like to see the animal advocacy movement invest slightly more heavily in protests. Protests currently receive a tiny portion of the movement’s resources and, given the limited evidence we do have, it’s plausible they are at least as cost-effective as interventions that receive much more of the movement’s resources, such as leafleting. Moreover, we think that the use of protests contributes to the diversity of tactics in the movement, which can help attract a greater number and variety of activists to the cause and thereby increase our chances of success.

In part because protesters employ a wide range of strategies, some protests are likely more effective than others. Of course, we believe that more resources should be devoted to more effective protests and fewer resources should be devoted to less effective protests. We have some uncertainty regarding which kinds of protests are most effective, but we do provide some provisional, evidence-based advice for organizing effective protests. For example:

- Take a compassionate, rather than a shaming tone at protests, and target institutions rather than individuals

- Contact the press to notify them of the protest and follow up with them afterwards

- Consider using protests in conjunction with other interventions, such as petitions, phone calls, leafleting, and email campaigns

- Consider organizing a series of protests, since protests and other activist challenges to corporations are likely more successful when repeated (both within a given campaign and in subsequent campaigns) at the same corporation

- Because some types of protests can pose a higher risk for protesters who have marginalized identities, organizers should:

- Understand and communicate the risks of protests to all activists

- Consider recruiting protesters with relatively privileged identities to engage in riskier activities

- Ensure that there are safe ways for activists to participate if they can’t or don’t want to attend a protest

Much of our general advice about supporting other movements is highly relevant for protesters. (For example: “Do not advocate for your issue in ways that are racist, sexist, heterosexist, cissexist, sizeist, ableist, ageist, classist, etc.”)

Our 2018 protest intervention report is guided by our recently updated intervention evaluation process, which provides a new framework for using multiple sources of evidence to evaluate an intervention’s effectiveness. The report includes, among other things:

- A rough estimate of the numbers and costs of animal advocacy protests in the U.S.

- A theory of change for protests, supported by a literature search

- A discussion of various questions that have a bearing on the effectiveness of protests in different contexts

- A case study analysis of The Humane League’s use of protests

- Conversations with various activists and organizers who have experience with protests

- A discussion of the variation of protest effectiveness in different contexts, with evidence-based tips for using protests effectively

We encourage readers to refer to the full report for a detailed explanation of ACE’s current views and reasoning about the effectiveness of animal advocacy protests.

Full Report

The organization of this report may differ slightly from the one described in our intervention evaluation guide, as the two projects were developed concurrently.

Table of Contents

Part One: Intervention Description and Outcomes

Intervention description

Protests occur when groups of activists join forces and confront an opponent in an attempt to spur change. Animal advocacy protests take many different forms, including but not limited to: rallies, demonstrations, picketing, sit-ins, marches, and vigils. Groups like Direct Action Everywhere (DxE) and Collectively Free stage small disruptive events in places that support the use of animals, including grocery stores, restaurants, and political rallies. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) stages public stunts intended to capture the attention of bystanders and perhaps the media. The Save Movement holds regular vigils at or near slaughterhouses, stockyards, and other facilities in order to “bear witness” to the suffering and slaughter of animals. Groups like The Humane League (THL) and Mercy For Animals (MFA) stage silent protests at targeted institutions and make highly specific demands.

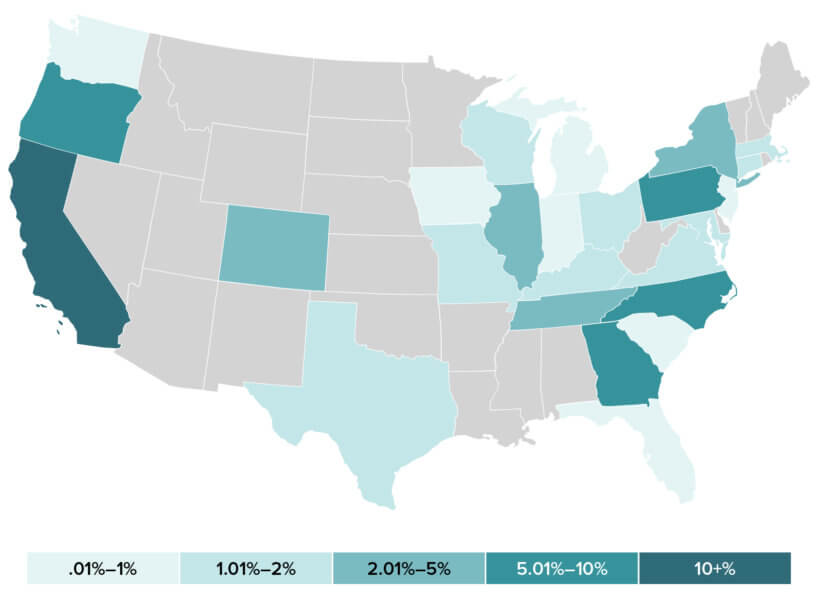

We estimate that there are 40–80 animal advocacy protests each week in the U.S. alone.1 We estimate that, together, Collectively Free, DxE, and PETA staged approximately 300–400 protests in 2016.2 These protests generally had no more than 200 participants, with an approximate median size of seven participants.3 The Save Movement holds approximately 850–1,000 vigils in the U.S. each year.4 We estimate that groups like THL and MFA organize approximately 60–100 additional protests each year as a component of corporate campaigns. Of course, many other groups and individuals also organize protests.

For the purpose of this analysis, we are investigating the effects of paradigmatic, nonviolent, disruptive5 gatherings of activists. We are particularly interested in the effects of the small gatherings inside or near places that support the use of animals (frequently organized by groups like DxE and Collectively Free). We are also interested in the effects of silent, highly targeted protests of corporations (frequently organized by groups like THL and MFA). We are not considering the effects of other related activities such as open rescues, canvassing, boycotts, strikes, property destruction, or acts of violence; those tactics likely have quite different outcomes and paths to impact.

Protest outcomes

| Positive |

|

|---|---|

| Negative |

|

| Positive |

|

|---|---|

| Negative |

|

| Positive |

|

|---|---|

| Negative |

|

Part Two: Theory of Change

Diagram

To communicate the process by which we believe protests create change, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not necessarily complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

|

Black arrows represent positive change for animals. |

|

Red arrows represent negative change for animals. |

|

Thinner arrows represent effects that we believe are relatively small. |

|

Thicker arrows represent effects that we believe are relatively large. |

|

We use dashed arrows to represent the effects that one type of outcome has on another type of outcome. |

|

Darker blue circles indicate the types of outcomes that we believe are relatively strongly influenced by the intervention. |

|

Lighter blue circles indicate the types of outcomes that we believe are relatively weakly influenced by the intervention. |

Evidence for our theory of change

In this section, we will provide some evidence for the relatively direct links between protests and the outcomes that are represented in our theory of change diagram. Since this project is mainly concerned with the direct effects of protests, we do not focus here on the effects of one outcome on another (e.g., the effects of public opinion on industry).7

Influencing public opinion

Protests seem to have a mixed effect on public opinion. On the one hand, protests likely elevate public awareness of animal welfare, particularly through media stories. (People who learn about protests from the news likely outnumber those who witness them in person, by far.) On the other hand, there’s some evidence that protest news items tend to be shorter and less balanced than non-protest items (Wouters, 2015). This suggests that there may be better approaches to media outreach.

One way that protests may draw non-activists into the movement is by producing “moral shocks:” situations that cause observers to be outraged. However, advocacy tactics that produce moral shocks can also backfire and produce extremely negative reactions in some witnesses (Mika, 2006).

Evidence from the Tea Party movement suggests that increased turnout at protests can influence public opinion favorably towards the protest’s cause (Madestam et al., 2013). On the other hand, protests may also damage public perceptions of activists, which can lower the public’s willingness to affiliate with the cause (Bashir et al., 2013). Feinberg et al. (2017) argue that the strongest predictor of mobilization is whether or not observers of collective action identify with the group being advocated for.8 They point to evidence that observers tend to distance themselves from anyone who is disruptive or challenges the status quo.9

| Author(s) | Year | Title | Approach | Context | Key Findings | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mika, M. | 2006 | Framing the Issue: Religion, Secular Ethics and the Case of Animal Rights Mobilization10 | Focus group research | Investigates reactions to real animal advocacy campaigns in the U.S. | Campaigns intended to produce “moral shocks” effectively reached some non-activists, but produced extremely negative reactions in others. | This is a study of reactions to animal advocacy campaigns in general, not protests in particular. Focus groups may be subject to effects like moderator bias. This study’s sample is small (52) and is composed entirely of college students. |

| Bashir, N. Y., Lockwood, B., Chasteen, A. L., Nadolny, D., Noyes, I. | 2013 | The Ironic Impact of Activists: Negative Stereotypes Reduce Social Change Influence | Randomized controlled trial | Investigates participants’ attitudes toward feminist and environmental activists | Participants’ negative stereotypes of activists were associated with lower “willingness to affiliate” with the activists. The authors suggest that negative social perceptions play “a key role in creating resistance to social change.” | The study investigated perceptions of “typical activists,” not specifically protesters. Also, perceptions of feminists and environmental activists may differ from perceptions of animal activists. |

| Madestam, A., Shoag, D., Veuger, S., Yanagizawa-Drott, D. | 2013 | Do Political Protests Matter? Evidence from the Tea Party Movement | Observational study (uses rainfall as an instrumental variable) | Investigates the effects of political protests | Survey evidence indicates that the Tea Party protests raised public outrage at the status quo as well as support for some of the Tea Party’s political views.11 | It’s unclear whether and to what extent evidence from the Tea Party movement generalizes to the animal advocacy movement. |

| Wouters, R. | 2015 | Patterns in Advocacy Group Portrayal: Comparing Attributes of Protest and Non-Protest News Items Across Advocacy Groups | Observational study | Investigates 17 Belgian advocacy groups | “[A]cross all advocacy groups, protest [news] items are less frequently balanced and significantly shorter than non-protest items.” | It’s unclear whether and to what extent evidence about news coverage of social movements in Belgium generalizes to news coverage of the animal movement in the U.S. |

| Feinberg, M., Willer, R., Kovacheff, C. | 2017 | Extreme Protest Tactics Reduce Popular Support for Social Movements12 | Randomized controlled trial | A working paper Investigating bystander support for three movements (including animal advocacy) immediately after reading about their protests | This study suggests that those protest tactics which get the most media attention (e.g., protests that are inflammatory, disruptive, counter-normative, or harmful to others) are associated with lower levels of popular support for the movement than other protests. | In the study of perceptions of animal activists, the two “extreme” treatment groups involved fictional stories of activists breaking into labs. The protests we investigate in this report do not involve illegal activity. Still, the “extreme” Black Lives Matter and anti-Trump protests used in the study did not involve illegal activity and also showed an effect. |

Other evidence of the effects of protests on public opinion

- We estimate that U.S. animal advocacy protests generate a minimum of 200 local, national, and international news stories each year.13

- Our informal online research14 of protests suggests that witnesses occasionally react positively to protests, and sometimes even vow to change their behavior.15 However, reactions of apathy or anger are far more common.

- Zach Groff, a former organizer for Direct Action Everywhere (DxE), tells us that, in his experience, the most common witness reactions to protests are apathy and amazement, followed by anger. He suggests that interacting one-on-one with witnesses (e.g., by leafleting during a protest) can lead to more positive reactions.16

- We have observed that, occasionally, protests increase sympathy and support for the target of the protest.17

Capacity building

Protests seem to have a mixed, but net positive, effect on the capacity of the animal advocacy movement.

One way that protests can build or deplete the movement’s capacity is through their effects on activists. Protesting may build capacity by drawing in new activists, providing them with a social network, raising their enthusiasm, and sometimes helping them build organizational, interpersonal, and public speaking skills that can be used in other forms of advocacy. They may also deplete the movement’s capacity by causing stress, legal trouble,18 problems with self-identity,19 and (very occasional) physical injury to activists.20 Some of these harms disproportionately affect activists with marginalized identities.21

Some activists might experience burnout or even retire from activism as a result of the harms of participation in protests. However, we often see that protesters react to setbacks with renewed commitment to their cause.22, 23 Some evidence suggests that anger in response to an unsuccessful protest and pride in a successful protest both predict intentions to continue protesting (Tausch & Becker, 2012). These findings are consistent with the dynamic dual pathway model of protest participation (van Zomeren et al., 2012).

There is weak evidence that protests lead to increases in grassroots organizing, the size of subsequent protests, and donations to the cause (Madestam et al., 2013). These effects may be due to the mobilizing influence of protesting on activists, since more committed and enthusiastic activists may be more likely to draw their social networks to the cause.

It’s possible that protest groups and other relatively extreme components of a movement can have either a positive or a negative effect on the efficacy of more moderate components of the movement. On the one hand, the extreme components (or “radical flanks”) might impose fear on the movement’s opponents, thereby giving moderate components greater leverage. On the other hand, radical flanks can lead to greater counter-mobilization. Chenoweth and Stephan (2011) write that “[t]here is no consensus among social scientists about the conditions under which radical flanks either harm or help a social movement.”

| Author(s) | Year | Title | Approach | Context | Key Findings | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Einwohner, R. | 2002 | Bringing The Outsiders In: Opponents’ Claims and The Construction of Animal Rights Activists’ Identity24 | Review | Uses three years’ worth of data from fieldwork with an animal organization | The perceptions of people outside of the animal advocacy movement (e.g., that animal activists are “overly emotional” or “irrational”) affect animal activists’ sense of self-identity. | It’s possible that there was something specific about the culture of the organization studied that influenced the results. |

| Chenoweth, E., Stephan, M. J. | 2011 | Why Civil Resistance Works, pgs. 42–46 | Case study research | Examines the effects of violent and nonviolent resistance on building alliances in the context of regime change | “Radical flanks” of a movement can have either positive or negative effects on the more moderate components of a movement. | Does not find a consensus regarding the conditions under which radical flanks have a net positive or net negative effect. |

| Van Zomeren, M., Leach, C. W., Spears, R. | 2012 | A Dynamic Dual Pathway Model of Approach Coping With Collective Disadvantage | Review | Considers previous social psychological research on protests | The authors propose a model that explains individuals’ motivation to protest. It emphasizes that (i) the decision to protest is driven by both a cost-benefit analysis and emotions (particularly anger), and (ii) the motivation to protest is dynamic. Participating in a protest can heighten participants’ motivations to continue protesting. | The authors propose a model of motivation to protest in response to collective disadvantage, not the motivation to protest specifically for animals. |

| Tausch, N., Becker, J. C. | 2012 | Emotional Reactions to Success and Failure of Collective Action as Predictors of Future Action Intentions | Longitudinal study | Investigates student protests in Germany | The authors investigate the role of emotional reactions to protests in motivating future participation in protests. They find that pride in a successful protest and anger at a failed protest both predict intentions to continue protesting. | As this was a longitudinal study, there may have been external influences on students’ reactions. Additionally, results from the one context may not generalize to others. Finally, intentions to continue protesting may not predict future behavior. |

| Madestam, A., Shoag, D., Veuger, S., Yanagizawa-Drott, D. | 2013 | Do Political Protests Matter? Evidence from the Tea Party Movement (same as above) | Observational study (uses rainfall as an independent variable) | Investigates the effects of political protests | The Tea Party seems to have raised turnout for Republican voters. The authors estimate that each Tea Party protester is associated with a 7 to 14 vote increase in Republican votes. Tea Party protests were also associated with increases in grassroots organizing, size of subsequent protests, and donations. | It’s unclear whether and to what extent evidence from the Tea Party movement generalizes to the animal advocacy movement. We suspect that Tea Party protests have a greater influence on the public than animal protests, in part because about 44% of Americans identify as or “lean” Republican and the Tea Party is associated with the Republican Party. |

| Stuart, A., Thomas, E. F., Donaghue, N. | 2015 | Social (Dis)incentives to Participate in Collective Action | Survey research | Investigates participants in social movements | The authors found that activists are often ambivalent about continuing to participate in collective action. Rather than stopping due to disinterest, activists often stop participating due to perceived social consequences and concerns about self-identity. | This is a manuscript, which has not been peer-reviewed or published. It concerns protests in general, not animal advocacy protests specifically. |

Other evidence of the effects of protests on the movement’s capacity

- Collectively Free, DxE, and The Save Movement, three organizations that organize protests, all seemed to grow quickly in size in their early years. Collectively Free was founded in New York City in 2014 and by 2017 they had established chapters in the USA, Canada, Mexico, and Australia. DxE was founded in 2013 in the Bay Area of California and by 2017 they had established at least 40 chapters in 13 countries. The Save Movement was founded in 2010 in Toronto, Canada and by 2017 has had over 170 chapters in more than 20 countries. (This evidence is anecdotal. We do not have data on the total number of animal organizations devoted to protests, the average rate of growth of such organizations, or the average rate of growth of animal organizations that do not use protests. It is unclear whether these quick growth rates will continue.)

- Taylor Ford, Director of Campaigns at The Humane League (THL), reports that THL’s protests seem to draw a group of volunteers who may not have gotten involved in animal activism through other interventions. He believes that organizing protests has helped THL build a support base in each of the cities where they have offices.

Influencing industry

Protests can affect positive corporate change, particularly when they are one component of a broader corporate outreach strategy.25 One way they can do this is by disrupting a corporation’s typical operations. When a corporation senses potential damage to its performance or reputation, it may take steps to resolve the problem (McDonnell et al., 2015). Another mechanism for protests’ success in this area is creating or heightening internal divisions in a corporation such that some people within the corporation advocate for changes (Soule, 2009; Chenoweth & Olsen, 2016).

Some evidence suggests that protests and other activist challenges to corporations are likely more successful when repeated within a given campaign. When Chenoweth and Olsen (2016) investigated activist challenges to corporations in the developing world, they found that “21% of civil resistance efforts that included only one event were successful in achieving partial or full accommodation of their requests, but 49% of efforts that included at least two events were successful; the more events, the more likely it was that the corporation made concessions.” Activist challenges to corporations may have an even higher success rate in the U.S.; Chenoweth and Olsen report that their success rate is positively associated with the “robustness” of the rule of law in the country in which they take place.

Protests are particularly successful when they target corporations with existing vulnerabilities (Jasper & Poulsen, 1993). McDonnell et al. (2015) argue that a campaign may be more successful if targeted against a corporation that has been the target of similar campaigns in the past. One way that corporations respond to activist threats is by developing “social management devices,” like board committees devoted to social responsibility. While these responses may be intended to protect the company’s image, they can incidentally increase the company’s accountability and receptivity to future challenges (McDonnell et al., 2015).26

| Author(s) | Year | Title | Approach | Context | Key Findings | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jasper, J. M., Poulsen, J. D. | 1993 | Fighting Back: Vulnerabilities, Blunders, and Countermobilization by the Targets in Three Animal Rights Campaigns27 | Case study research | Examines campaigns to end research on animals at three separate U.S. institutions | The authors attribute campaign successes to corporate vulnerabilities, including internal divisions, particularly unpopular practices, and making strategic mistakes. They argue that organizations can learn better ways to respond to activists. They suggest that movements may become less effective as they become more visible. | It’s unclear whether and to what extent the conclusions drawn from case studies can be generalized, especially because it is from 1993 and does not account for more recent data. This piece does not consider possible benefits of greater visibility for social movements. |

| Soule, S. A. | 2009 | Contention and Corporate Social Responsibility | Book | A history and analysis of direct challenges to U.S. corporations by social movements | This book argues that civil resistance targeting corporations has increased in recent decades. Suggests that civil resistance to organizations may be particularly effective when the organizations are undergoing leadership changes or experiencing internal divisions. | This book examines civil resistance generally, not animal advocacy protests specifically. |

| McDonnell, M., King, B. G., Soule, S. A. | 2015 | A Dynamic Process Model of Private Politics | Longitudinal data analysis | Tracks 300 large companies between 1993 and 2009 | The authors propose a dynamic process by which activist challenges lead corporations to become more receptive to social concerns over time. | This study investigates the effects of activist challenges generally, not protests specifically. |

| Chenoweth, E., Olsen, T. | 2016 | Civil Resistance and Corporate Behavior | Literature review and pilot study | Observed the effects of civil resistance to corporate human rights abuses in Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, and South Africa | This piece suggests some important lessons for predicting the success of direct action targeting corporations. For instance, multiple events are more effective than one-off events. Corporations operating in countries with “more robust rule of law” are more likely to make concessions to protesters than other corporations. | This was just a pilot study and did not establish any causal claims. It’s unclear whether and to what extent lessons about resistance to human rights abuses in the developing world generalize to resistance to animal rights abuses in the U.S. |

Other evidence of the effects of protests on industry

- Ford believes that protests have played an important role in some of THL’s successful corporate campaigns, including those against Farm Foods and Subway.

- According to Global Campaigns Manager Mikael Roldsgaard Nielsen, MFA has used protests as a component of successful corporate campaigns, including a recent campaign against Safeway.

- In 2016 the Ringling Bros. Circus announced that they would no longer use elephants in their acts.28 In 2017, they announced plans to close, citing a drop in ticket sales. Animal activists have been protesting the circus since at least 1980. We believe that protests bear some responsibility for the circus’ closure, though it’s not clear precisely how much.29

- Occasionally, small, disruptive protests achieve small changes—such as altering or shutting down events.30

Building alliances

It seems highly plausible that protests can help the animal advocacy movement to build alliances with sympathetic politicians or other influencers. Some animal activists have used protests to build alliances with other social justice movements, which we believe is a neglected goal within the animal advocacy movement as a whole.

Large, high-profile protests seem more likely than small, low-profile protests to prompt key influencers to adopt and/or voice a position. Chenoweth and Stephan (2011) report that in their survey of regime change efforts, the chance that the largest campaigns made alliances with defectors from the security force was more than 50% greater than the chance that the smallest campaigns made such alliances.

Most likely, if high-profile protests can prompt key influencers to become allies with the protest group, they can also prompt key influencers to become opponents for the protest group. In fact, in 2017 DxE used the threat of continued protests to convince a Berkeley meat shop to post a sign in their window acknowledging that “killing [animals] is violent and unjust.” Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguin responded in a statement that the protests were “harassment—plain and simple.” Having asserted in the same statement that he “respect[s] people’s passion for social causes as well as their right to express their opinions,” it’s possible that Arreguin might have supported the animal activists had they used different tactics.

While we believe that protests can build both alliances and opposition between a movement and powerful influencers in theory, we have little evidence that protests have had many such effects within the animal advocacy movement thus far. Perhaps few animal protests have been sufficiently high-profile to capture key influencers’ attention. It may also be because, as Tarrow points out, “elites are unlikely to be persuaded to make policy changes that are not in their own interest” (168).

| Author(s) | Year | Title | Approach | Context | Key Findings | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tarrow, S. | 2011 Ed. | Power in Movement, Chapter 8 | Book (draws from case studies and social movement theory) | A frequently cited book on social movement theory | Tarrow suggests that protests present opportunities for political elites to take a position on an issue. However, politicians are unlikely to adopt any position that is not in their interests, so they are rarely moved to do so by protests alone. | Tarrow studied social movements for human-related causes. |

| Chenoweth, E., Stephan, M. J. | 2011 | Why Civil Resistance Works, pgs. 46–50 | Book (draws from case studies and social movement theory) | Examines the effects of violent and nonviolent resistance on building alliances in the context of regime change | Nonviolent resistance can cause members of the elite or of the elite’s supporting forces (e.g., security forces) to shift loyalties or sympathies. The authors report that “the largest nonviolent campaigns have about a 60% chance of producing security-force defections.” | Civil resistance movements aimed at overthrowing a regime are quite different from the animal advocacy movement in the U.S. For instance, regime change campaigns have more specific and tangible opponents. |

Other evidence of the effects of protests on the movement’s alliances

- During the 2016 Democratic primaries, approximately one month after DxE activists first disrupted a rally for Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton added a page to her website about “protecting animals and wildlife.” It’s unclear whether the page was added in response to the disruption, but the timing is suggestive.31

- Some protests offer an opportunity for animal activists to build alliances with other movements. For instance, Mercy For Animals has participated in Pride parades. Collectively Free activists integrated anti-sexist and anti-homophobic messages into their protests of Chick-Fil-A. Other animal activists have participated in environmental protests and found environmental activists to be receptive to their message.

Influencing policy and law

There is some evidence from other movements that protests can influence policy and law. As Sidney Tarrow explains, “disruption obstructs the routine activities of opponents, bystanders, or authorities and forces them to attend to protesters’ demands.” It also “broadens the circle of conflict. By blocking traffic or interrupting public business, protestors inconvenience bystanders, pose a risk to law and order, and draw authorities into what was a private conflict” (101).

Walgrave and Vliegenthart (2012) found that protests influenced the political agenda in Belgium. While political agenda-setting does not necessarily lead to policy change, it may be a necessary precursor. The Tea Party protests seem to have had a clear effect on U.S. policy, though we believe that the political influence of the Tea Party was likely greater than the potential political influence of the animal movement—due in part to the Tea Party’s overtly political nature and association with a major political party.

Based on evidence from the 1960s’ black insurgency, Wasow (2017) argues that protests can affect policy by influencing political elites, swaying public opinion, and changing voting patterns. It appears that protests can also influence policy by amplifying the political effects of public opinion. For instance, Agnone (2007) found that environmental protests increased the political effects of public support for environmental legislation. This finding is consistent with Giugni and Yamasaki’s (2009) conclusion that protests hold more political power when they have greater public support, as well as more political alliances.

| Author(s) | Year | Title | Approach | Context | Key Findings | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agnone, J. | 2007 | Amplifying Public Opinion: The Policy Impact of the U.S. Environmental Movement | Observational study (uses time-series analysis) | Studies protests in the U.S. environmental movement | This study suggests that protests impact policy by amplifying the policy effects of public opinion. | The study only investigates the effects of protests that were covered in The New York Times before 1998. It’s unclear whether and to what extent studies of environmental protests generalize to animal protests. |

| Giugni, M. G., Yamasaki, S. | 2009 | The Policy Impact of Social Movements | Reanalysis of a previous study (uses qualitative comparative analysis) | Investigates the policy impact of antinuclear, ecology, and peace movements (measured by protest activity) in the U.S., Switzerland, and Italy | This reanalysis finds support for a joint-effect model of social movement outcomes, suggesting that powerful alliances and public support both increase the policy impact of social movements. | It’s unclear whether and to what extent research on antinuclear, ecology, and peace movements generalizes to the animal advocacy movement. |

| Tarrow, S. | 2011 Ed. | Power in Movement | Book (draws from case studies and social movement theory) | An important book on social movement theory | Disruptive action can create change by (i) demonstrating activists’ determination, (ii) obstructing routines, and (iii) posing a risk to “law and order.” | Tarrow studied social movements for human-related causes. |

| Walgrave, S., Vliegenthart, R. | 2012 | The Complex Agenda-Setting Power of Protest: Demonstrations, Media, Parliament, Government, and Legislation in Belgium, 1993–2000 | Observational study (uses time-series analysis) | Measures the political agenda in Belgium from 1993–2000 | Suggests that protests influence the political agenda, but that the causal mechanisms underlying their effects are “complex and contingent.” Finds that mass media plays a mediating effect. | This study does not measure actual policy change. Though it’s a study of Belgium’s political system, which is smaller and more fragmented than the U.S. political system, the authors “cautiously corroborate” findings from similar studies in the U.S. |

| Madestam, A., Shoag, D., Veuger, S., Yanagizawa-Drott, D. | 2013 | Do Political Protests Matter? Evidence from the Tea Party Movement (same as above) | Observational study (uses rainfall as an independent variable) | Investigates the effects of political protests | This study suggests that the Tea Party protests affected policy through the political activity of incumbents as well as through elections. In addition, the protests’ effects on public opinion led more Democratic incumbents to retire. | It seems likely that the Tea Party would exert much greater political influence than the animal advocacy movement, since the Tea Party is an overtly political movement and is associated with a major political party. |

| Wasow, O. | 2017 | Do Protests Matter? Evidence from the 1960s Black Insurgency | Observational study | A working paper using data on protest activity, Congressional speeches, public opinion, and voting patterns during the 1960s black insurgency | This study suggests that protests can affect policy by influencing political elites, swaying public opinion, and changing voting patterns. | It’s unclear whether and to what extent we can generalize from the black insurgency to the animal advocacy movement, especially given the extent to which civil rights dominated social discourse in mid-1960s. |

Other evidence of the effects of protests on influencing policy and law

- When the Berkeley Animal Rights Center (ARC) was threatened with eviction, activists rallied outside of City Hall and attended a City Council meeting. At the meeting, the council amended the ARC’s lease to ensure their right to stay. It is unclear to us whether the council was influenced by the rally.

- Shortly before the Berkeley City Council voted to ban the sale of fur in Berkeley, DxE staged a protest of over 100 people in support of the ban. Jay Quigley, secretary for the Berkeley Coalition for Animals (BCA), tells us that in his view, the most important factors in passing the ban were the personal relationships between BCA activists and councilmembers. The second most important factor, in his view, were petitions and email campaigns. Quigley feels that the protest was primarily helpful for mobilizing activists to care about the campaign.32, 33

Discussion

The above table includes some evidence for each of the mechanisms represented in our theory of change. However, many of the studies cited above have important limitations. For example:

- Perhaps most importantly, some of them do not directly investigate the impact of protests, but of civil resistance, direct action, or other more general approaches. Most of them investigate social movements other than the animal advocacy movement. The animal movement seems relevantly different from many other movements, particularly those that are closely associated with major political parties or those with which large portions of the population identify.

- Many of the studies of attitude or behavior change are short-term studies, though we are at least as interested in the longer-term effects of protests on attitudes and behavior.

- Many studies of participants’ reactions to protests use interventions that are importantly different from the way people are typically exposed to protests.

- Some of the research includes historical case studies, which (i) may be subject to survivorship bias and (ii) present difficulties for drawing conclusions about causation.

Despite these limitations, we believe that the body of evidence presented above suggests that protests can, at least in some contexts, influence public opinion, the movement’s capacity, industry, alliances, and policy. These outcomes can lead to meaningful social change. We think that, if protests are an effective animal advocacy intervention, they are most likely effective via their production of these outcomes in the ways described above.

Overall, we think that the strength of the evidence supporting this theory of change is moderate(but closer to “weak” than “strong”):

| Poor | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

| Little is understood about the underlying causal mechanisms of this intervention. | There is some understanding of the underlying causal mechanisms of this intervention, weakly supported by evidence. | There is a good understanding of the underlying causal mechanisms of this intervention, moderately supported by evidence. | There is a strong understanding of the underlying causal mechanisms of this intervention, tested and supported by evidence. |

Part Three: Discussions of Protest Effectiveness

While there is some research suggesting that protests can produce both positive and negative outcomes for animals, many additional questions have a bearing upon the effectiveness of protests as an animal advocacy intervention. For example:

- To what extent can we draw lessons from other movements about the effectiveness of protests in the animal advocacy movement?

- Does the effectiveness of protesting change throughout the development of a movement?

- Are there other animal advocacy interventions that produce the same positive outcomes as protests, particularly without producing negative outcomes?

- Are protests a necessary component of successful movements?

Experimental research cannot fully resolve all of these questions, but there has been some relevant discussion of these questions among animal advocates and social movement theorists. In this section, we summarize some of those discussions.

To what extent can we draw lessons from other movements about the effectiveness of protests in the animal advocacy movement?

Much of the evidence regarding the effects of protests comes from studies of other movements, usually for human-related causes. Felsinger (2016) argues that the animal advocacy movement is importantly different from human rights movements, and that the success of protests for human rights movements does not necessarily imply that protests will lead to success for the animal advocacy movement. Progress for human rights, he argues, has often simply required the public to accept new laws, but not to significantly change their behavior. On the other hand, achieving legal rights for animals will require changing individuals’ “habitual behaviors.” Felsinger suggests that prohibiting the sale of meat, for instance, will face public opposition similar to that of failed efforts like alcohol prohibition or the war on drugs.

In a response to Felsinger, Groff (2016) argues that the goals of the animal advocacy movement are perhaps not as radical as they seem. He suggests that there are “more regulations on [the use of animals] than there were laws protecting other oppressed classes before their movements started.” This is consistent with Felsinger’s point; it’s possible that the animal movement is both less radical than many human rights movements (in the sense that animals might already have more legal protection than other groups) and more radical than many human rights movements (in the sense that its progress will require more change from more individuals). However, there do seem to be important counterexamples to the claim that the animal rights movement requires more change from individuals than previous movements; for instance, the abolition of the slave trade, the civil rights movement, and various battles for women’s rights have all deeply permeated the lives of individuals in the U.S. Moreover, emerging food technology like cultured meat may well decrease the personal demandingness of animal rights advocacy.

It’s tempting to think that, if the goals of the animal advocacy movement are easier to achieve than—or similar to—the goals of other movements, tactics that work for other movements should work for the animal advocacy movement. Similarly, it’s tempting to think that, if the goals of the animal advocacy movement are harder to achieve than the goals of other movements, tactics that work for other movements will not necessarily work for the animal advocacy movement. In Why Civil Resistance Works, Chenoweth and Stephan explain that they deliberately chose to study “maximalist” movements, including regime change, anti-occupation, and secession movements. They suggest that “campaigns with goals that are perceived as maximalist (fundamentally altering the political order) may be less likely to succeed than goals perceived as more limited in nature (e.g., finite political rights) (69). According to Perry (2015), Chenoweth believes that her findings should generalize to the animal movement.34

Even if the goals of the animal movement are—in at least some ways—relatively modest, it doesn’t follow that tactics that have worked for other movements will necessarily work for the animal movement. The animal movement seems relevantly different from human rights movements in many ways, aside from the ambition of its goals. First of all, in contrast with the movements studied by Chenoweth and Stephan, it’s not entirely clear what the animal advocacy movement’s goals are, or whether all animal advocates agree on them.35, 36 Unlike the movements studied by Chenoweth and Stephan, the animal movement doesn’t have a specific state adversary. Some of the movements Chenoweth and Stephan studied had support from external governments,37 whereas the animal movement seems to have few powerful allies. The animal advocacy movement might be less diverse than other movements. Finally, the animal rights movement is not directly led by a disenfranchised group, but rather by its allies.38 Such differences might have a bearing upon the effectiveness of various tactics. We think it is an open question whether (and to what extent) the lessons of other movements generalize to the animal advocacy movement.

| Author(s) | Year | Title (Link) | Venue or Publisher | Context | Key Findings |

| Felsinger, A. | 2016 | Direct Action Leading Where?39 | Medium | An essay that raises some questions about the research that is often taken to support the effectiveness of protests | This essay argues that the animal advocacy movement is importantly different from other movements and that it should focus on education and earning greater credibility before mobilizing for protests. |

| Groff, Z. | 2016a | Four Reasons Why Direct Action Leads to Animal Liberation40 | Medium | A response to Alex Felsinger’s essay, written by former DxE organizer Zach Groff | This response argues that the animal advocacy movement is similar to other movements in some respects, and it should use protests in order to mobilize more activists. |

| Perry, J. | 2015 | Why Vegans Should Pick Up a Protest Sign41 | DxE Blog | A brief summary of a conversation between Erica Chenoweth and DxE activists, with a link to their notes | According to DxE activists, Chenoweth believes that her findings should generalize to the animal movement. She also notes that the animal advocacy movement may be more controversial than many of the movements she’s studied. |

Does the effectiveness of protesting change throughout the development of a movement?

The effectiveness of protests likely depends on many factors that can change throughout the development of a movement. Perhaps most importantly, it seems to depend on the number of people who are mobilized to participate in the protests. Chenoweth and Stephan found that, for protest movements, “[t]he trend is clear that as membership [i.e., the number of participants in a movement] increases, the probability of success also increases” (39).

The idea that larger protest movements are more effective than smaller ones raises several important questions for the animal advocacy movement. If protests are ever an effective use of resources, at what level of participation are they effective? Similarly, if protests are ever a counterproductive use of resources, at what level of participation are they counterproductive?

According to Chenoweth (2013), all major nonviolent resistance movements that have achieved the participation of 3.5% of the population have succeeded.42 Some animal activists seem to take her research as evidence that, once a movement achieves sufficient support, protests can cause it to succeed. For example, DxE activists frequently argue that “[i]f we can mobilize 3.5% of the population in sustained and nonviolent direct action, we can almost certainly win.”43 Some animal activists also seem to take Chenoweth’s research as evidence that protests are effective for the animal advocacy movement now, though it has not yet mobilized 3.5% of the population.44 “Although I do not think that 0.00058% of the population mobilized is enough to change the world,” argues Zach Groff (2016b) “[…] a small mobilization is the best way to get to a larger one.”

We take Chenoweth’s work to be only weak evidence for the claim (made by activists) that protests cause movements with at least 3.5% mobilization to succeed. It might be that achieving a high level of protest mobilization and succeeding are correlated because they have a common outside cause. For instance, in the cases of civil resistance that Chenoweth studied, the unpopularity of the ruling government might have caused both higher levels of participation and eventual success. We do think it’s plausible that protests can help small movements grow into larger ones because of the evidence we summarized in the “Capacity Building” section of Part Two of this report. We are not sure, however, whether protests are the best way to help a movement grow.

While protests may help small movements begin to mobilize, it’s also possible that protests produce more unwanted effects for smaller movements than they do for larger ones. Felsinger (2016) argues that protests reinforce stereotypes of vegans and might dissuade the public from “participating in radical action due to their fears of social ostracism.” It seems this risk would be mitigated if more of the public participated in and normalized protests.

Aside from the relatively low level of participation in today’s animal advocacy protests, there may be other reasons why protesting now is less likely to succeed than protesting later. Protests might be more effective after the animal movement achieves more public support or more powerful allies. Of course, it’s possible that, even if protesting would be more effective later than it is now, it’s still an effective tactic now. However, because it can be difficult to sustain a protest movement over a long period of time,45 it may be unwise to invest significant resources in protests before they have their best chance of succeeding.

| Author(s) | Year | Title (Link) | Venue or Publisher | Context | Key Findings |

| Tarrow, S. | 2011 Ed. | Power in Movement | Cambridge University Press | This is an important book on social movement theory that explores (i) the development of the modern social movement, (ii) political opportunities and threats for movements, and (iii) the dynamics of collective action. | Tarrow argues that disruptions are a social movement’s “strongest weapon,” but that they are difficult to sustain. |

| Chenoweth, E., Stephan, M. J. | 2011 | Why Civil Resistance Works | Columbia University Press | This is an important book that analyzes data from 323 regime change, anti-occupation, and secession campaigns and compares the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance to violent resistance. | This book provides some of the most compelling large-scale evidence for the effectiveness of nonviolent protests. The authors find that mobilization correlates with success for protest movements. |

| Chenoweth, E. | 2013 | My Talk at TEDxBoulder: Civil Resistance and the “3.5% Rule” | TEDx talk and blog post | In this talk Erica Chenoweth presents some of her research at TEDxBoulder. | All of the resistance movements in Chenoweth’s study which achieved the participation of 3.5% were nonviolent, and all of them succeeded. |

| Groff, Z. | 2016 | A (Potential) Summary of Disagreements and Agreements on Direct Action46 | Medium | A summary of the points of agreement (and disagreement) between Felsinger and Groff, written by Groff. | A main point of contention between Felsinger and Groff is whether protests can be successful without robust mobilization. |

| Shooster, J. | 2017 | Polls Show America is Ready for Aggressive Animal Advocacy47 | The Huffington Post | Uses Gallup polls to argue that Americans are ready for animal protests. | Argues that, while favorable public opinion is not necessarily essential for the success of a social justice movement, at least some animal advocacy messages have at least as much public support as other social justice causes that use protests. |

Are there other animal advocacy interventions that produce the same positive outcomes as protests, particularly without producing negative outcomes?

If the primary purpose of protesting at this early stage in the animal advocacy movement is to mobilize activists, it’s worth considering whether there other ways to mobilize activists that have fewer drawbacks. In his presentation at the 2017 National Animal Rights Conference, Jacy Reese48 notes that one way that protests mobilize activists is by creating moral outrage. As we noted in Part Two of this report, creating moral outrage (or “moral shocks”) can mobilize some individuals, but it can also produce extremely negative reactions in others. Reese wonders whether there are other ways to mobilize that are less likely to backfire. He recommends open rescues and investigations, though he thinks that if the media becomes saturated with information from open rescues and investigations at some point,49 those interventions may have diminishing returns.

Other interventions that could perhaps accomplish the same positive outcomes as protests (with fewer drawbacks) are local political organizing and the development of new food technology. Local political organizing can have a mobilizing effect but carries a lower risk of countermobilization. It could also be argued that the development of new food technology will ultimately do more than protests to mobilize the animal advocacy movement, with very few drawbacks. Providing omnivores with alternatives to animal products may decrease individuals’ resistance to the movement.

| Author(s) | Year | Title (Link) | Venue or Publisher | Context | Key Findings |

| Reese, J. | 2017 | The Power of Confrontation in Advancing Animal Rights50 | Presentation at the National Animal Rights Conference | This is a presentation by Jacy Reese, previously a Researcher at ACE and currently Director of Research at Sentience Institute. | Reese suggests that confrontational tactics can cause change by inspiring moral outrage, and discusses whether other interventions can cause moral outrage with less risk of backfiring. |

Are protests a necessary component of successful movements?

Even if protests are less effective than other animal advocacy interventions at this stage in the animal advocacy movement, it still may be the case that they are necessary for the success of the movement (and thus, highly effective at least up to some threshold). If so, we should surely continue to allocate resources towards them一though it may remain an open question whether we should allocate greater, fewer, or the same amount of resources that we have in the past.

One argument for the necessity of protests is that they may be the only way for animal activists to express that they will not settle for anything less than radical change.51 Without continually demanding radical change, it may be that the animal movement would achieve some limited welfare reforms for animals and then stagnate. In fact, we have already achieved some welfare reforms, and there’s a reasonable concern that they could lead to public complacency or misconceptions about the conditions on industrial farms (Francione, 2008).

It may even be that the use of protests has been necessary for achieving the types of welfare reforms we’ve already achieved. There is some evidence that using relatively extreme tactics can improve the effectiveness of relatively moderate tactics. Robnett and Trammell (2004) argue that a movement’s “radical flanks” (i.e., relatively extreme components) tend to increase the effectiveness of more moderate components of the movement “during the peak of activism,” before significant concessions are won.52

Another argument for the necessity of protests (and the last one we will consider here, though there may be others) is based on the premises that: (i) it may be necessary for the animal advocacy movement to use protests in order to align itself with other social justice movements, and (ii) it may be necessary for animal advocacy movement to align itself with other social justice movements in order to succeed.53

One reason to think the movement must use protests in order to align itself with other social justice movements is that, historically, nonviolent protest has been a hallmark of social justice movements.54 It may be that, in order to build bridges with today’s social justice movements, the animal advocacy movement must emphasize its similarities to those movements by using similar tactics and standing in opposition to all forms of oppression.

One reason to think the movement must align itself with other social justice movements in order to succeed is that joining a coalition of movements might cause it to resonate with a much larger, more diverse segment of the population. Some of the most compelling evidence for the movement building and policy-influencing effects of protests comes from Madestam et. al’s (2013) study of the Tea Party movement,55 but it seems likely to us that a larger portion of the population identified with the Tea Party movement than with the animal movement because the Tea Party movement was associated with a major political party from its inception.56 The animal advocacy movement might benefit from a similar association with the political left. It’s true that associating with the political left will likely alienate some potential animal allies on the right, but the benefits of an alliance with a major political movement might outweigh the costs. Moreover, insofar as the animal advocacy movement is already associated with the political left, animal advocates who make an active effort to remain politically neutral may alienate some potential allies on the left.

We think it’s likely that the animal advocacy movement would benefit from presenting a more unified front with other social justice movements, but we think it’s unclear whether doing so is necessary for its success.57 Moreover, if protesting in order to align with other movements is necessary for its success, it’s still possible that the animal movement should focus on movement building now and protesting later.

| Author(s) | Year | Title (Link) | Venue or Publisher | Context | Key Findings |

| Robnett, B., Trammell, R. | 2004 | Negative and Positive Radical Flank Effects on Social Movements: The Influence of Protest Cycles on Moderate and Conservative Organizations | Presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association | Examines data from the Civil Rights movement and the AIDS social movement | This presentation argues that “radical flanks” can make more moderate components of a movement either more effective or less effective depending on the stage of the movement’s development. |

| Francione, G. | 2008 | Animals as Persons: Essays on the Abolition of Animal Exploitation | Columbia University Press | A series of essays arguing against the regulation of animal welfare and for the abolition of all human uses of animals | These essays argue, among other things, that humane reforms “may actually increase consumption by people who had stopped eating animal products because of concerns about treatment and will certainly provide as a general matter an incentive for continued consumption of animal products” (16). |

Discussion

Many open questions remain that have a bearing upon the effectiveness of protests for the animal advocacy movement. We hope that further research will investigate these questions so that we can make more informed, evidence-based decisions about how to allocate our movement’s resources. In particular, we hope to see further research on the features of movements that influence the effectiveness of protests, specifically those that may change throughout the movement’s development. Tarrow emphasizes that, while disruptive protests are a movement’s “strongest weapon,”58 they are “by no means the most common or the most durable” (103). Because protests can produce negative effects and they can be difficult to sustain, it seems critical for a movement to begin implementing protests only when they are reasonably likely to succeed.

One source of evidence that we are watching with interest is the growing animal advocacy movement in Berkeley, CA. DxE considers Berkeley to be their “seed city;” the concentration of animal activists is higher there than it is elsewhere, and DxE hopes to build a “critical mass” of support and, eventually, restrict the sale of meat in the city. We will be watching to see whether protests are more effective in Berkeley, where they have a relatively high level of participation, than they have been in other parts of the country. Of course, if they are, it might still be the case that we should focus on other forms of movement building in the rest of the country before investing further in protests.

Overall, while there are some compelling arguments for the necessity of protests in the animal advocacy movement, the current evidence supporting the effectiveness of animal advocacy protests is weak, relative to other interventions.59, 60

| Poor | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

| There is little to no evidence to support this choice of intervention. Or, the evidence suggests an intervention may have no effect or a negative impact. | There is weak evidence to support this intervention but it is either exploratory in nature, weak in effect, or the studies are of low quality. | There is moderate evidence to suggest this choice of intervention. | There is strong, high quality evidence to support this choice of intervention. |

Part Four: Case Study Analysis

Case studies provide a useful way to gain insight into implementations of an intervention as well as providing data for a cost-effectiveness analysis. Case studies can provide rich data, though it is usually at the expense of generalizability.

We completed a case study of The Humane League’s (THL’s) protest program following our conversation with Taylor Ford, Director of Campaigns at THL.

Case study: The Humane League

| People Interviewed | Taylor Ford, Director of Campaigns |

|---|---|

| Other Data Sources | ACE’s 2017 cost-effectiveness model for THL |

| Description of Intervention | THL uses protests as one component of their corporate campaigns |

| Implementation Description | THL recruits volunteers to silently protest restaurants or corporations by standing in a line outside holding signs. There is a trained organizer present at each protest who can speak with the target of the protest or the press as needed. THL uses protests in conjunction with other interventions, such as leafleting and delivering petitions. |

| Costs |

|

| Indicators of Success |

|

| How does this intervention work, according to the interviewee? | According to Ford, THL’s protests work by two primary mechanisms:

|

| Were there outside factors/influences that may have influenced outcomes?

Were there indicators to suggest that the interventioncaused any of the measured changes? |

Since THL combines protests with other interventions, there are many other factors that could contribute to the success of their corporate campaigns. However, there are some indications that protests have been responsible for some of their corporate outreach achievements. For instance, they have occasionally obtained a pledge from a corporation very soon after organizing a protest, when their other interventions hadn’t been working. |

Our case study suggests that protests can be an important component of successful corporate campaigns. When a corporation makes a concession to an animal charity, it is often hard to know how much responsibility to attribute to the charity. It’s even harder to know how much responsibility to attribute to the charity’s protests in particular. Still, Ford noted some signs that THL’s protests do have a causal impact on corporate activity. For instance, he notes a campaign that did not succeed for months, and finally succeeded two days after THL organized their first protest against the corporation.61

Based on our case study, we estimate that THL’s protests spare approximately -50–15062 farmed animal years per dollar.63 These ranges are our 90% subjective confidence intervals. The wide range of our estimates indicates our high degree of uncertainty about the cost-effectiveness of THL’s protests. For more information, see our cost-effectiveness model.

Discussion

Because THL uses protests as part of their exceptionally successful corporate campaigns program, their protests are probably more cost-effective than most. We expect that protests that are not part of a corporate campaign are not nearly as cost-effective, at least in terms of effects that are relatively short-term and easily measurable.

All protests likely have difficult-to-measure, longer-term outcomes that we are unable to account for in our cost-effectiveness models. Perhaps most importantly, we are not currently able to measure the effects of capacity building in terms of animals spared or years of suffering averted per dollar.

We did not make a cost-effectiveness estimate for smaller, grassroots protests because their impact is primarily long-term and difficult to measure. However, we did make a rough estimate of the cost of such protests, as well as the total costs of U.S. protests each year. Whereas we estimate that THL’s protests cost approximately $140–$550 each, we estimate that smaller, grassroots protests cost approximately $15–$65 each. We estimate that, in the U.S., the animal advocacy movement currently invests approximately $120,000–$240,000 in protests each year. These ranges are our 90% subjective confidence intervals. For more information, see our model of the numbers and costs of U.S. protests.

While our cost-effectiveness estimate for THL’s protests was highly uncertain, our conversation with Taylor Ford provided weak evidence to support the use of protests in corporate campaigns:

| Poor | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

| Development of a case study did not provide evidence to support this intervention choice. | The case study provided weak evidence to support this intervention choice. | The case study provided moderate evidence to support this intervention choice. | The case study provides strong evidence to support this intervention choice. |

Part Five: Conversations in the Field

Conversation summaries

To learn more about the use of protests as an animal advocacy intervention, we spoke with:

- Raffi Ciavatta and Lili Trenkova of Collectively Free

- Taylor Ford of The Humane League

- Zach Groff of the Save Movement (formerly of Direct Action Everywhere)

- Mikael Roldsgaard Nielsen of Mercy For Animals

We asked each activist why they protest, how they think protests effect change, and how they measure the success of their protests. Summaries of our conversations are available at the links above. We only spoke with animal advocates who choose to engage in protests, so the opinions of the people we spoke with may be systematically more positive towards protests than the opinions of most animal advocates.

Discussion

The activists we spoke with conduct protests in different ways. The Humane League (THL) and Mercy For Animals (MFA) use protests as one tool to convince corporations to implement specific changes. Both THL and MFA make an effort to organize protests that appear professional. Their demonstrations are silent, with neatly arranged signs and protesters in business attire. They use messages that can be communicated to the media clearly and effectively. Whereas MFA has moved towards organizing one-off protests, THL is moving towards organizing ongoing protests at the same location. THL also holds multiple protests targeted at the same company in different cities. Their goal is to reach local management in different cities and have the local management contact upper management.

Collectively Free’s and DxE’s protests are usually not intended to pressure a corporation to make a specific concession. Rather, they are designed to draw attention and challenge or disrupt the status quo. These groups are more inclined to take dramatic actions in unexpected places. For instance, Collectively Free protested inside St. Patrick’s Cathedral and DxE protested several Bernie Sanders rallies. Both organizations counted these events among their biggest successes, in part because of the attention they generated.

We asked each organizer which factors contribute to protest success. Ciavatta and Trenkova find that more creative, theatrical protests lead to better engagement with audiences. They report that “[t]here is a lot of luck involved in organizing a successful protest, and it also requires a lot of persistence.” They recommend alerting the press to the best protests and following up afterwards. Ford emphasizes the importance of strategically choosing the time and place of each protest, as well as combining protests with other interventions, like leafleting, petitioning, and phone calls. Groff cited research on the importance of avoiding violence at protests. He also emphasized that in order for protests to positively influence the movement, it’s important for activists to leave each protest feeling “energized and excited for change, rather than exhausted or otherwise disempowered.” Finally, Nielsen mentioned the importance of considering the visual impact of each protest in order to improve the likelihood of gaining media attention. MFA makes an effort to set their protests against a backdrop that features the name of the target, and they use professionally printed signs and wear professional attire.

Our conversations seemed to provide support for our theory of change for protests. Groff and Nielsen both mentioned that protests tend to get mixed reactions from witnesses,64 though Groff, Nielsen, and Ciavatta all agreed that influencing public opinion is not the primary goal of protests.65 Ford and Groff both noted that protests seem to be an effective way to draw new activists to the cause; in fact, they both feel that movement building is one of the primary ways that protests achieve change.66 Ford and Nielsen both report that protests have been components of successful campaigns to influence industry, and Groff reports that DxE protests have had some influence on corporations like Whole Foods and Costco.67 Ciavatta, Trenkova, and Groff agree that protests can provide an avenue for building bridges with other movements, though Ciavatta and Trenkova warn that not every protest is a good opportunity for multi-issue activism (because trying to connect animal advocacy to other issues can be seen as derailing) and Groff points out that other interventions, like leafleting, can also be used to advocate for multiple issues at once.68 Our interviews did not focus on the long-term effects that protests might have on law or policy, though Groff noted that the current political context (in which there have been many high-profile protests) may lead to a period of institutional instability in which protests are more likely to achieve institutional change.

Overall, our conversations with activists and organizers provided moderate evidence to support the effectiveness of protests, particularly when they are one component of a larger corporate strategy.

| Poor | Weak | Moderate | Strong |

| Our field conversations do not provide evidence to support this intervention choice. | Our field conversations provide weak evidence to support this intervention choice. | Our field conversations provide moderate evidence to support this intervention choice. | Our field conversations provide strong evidence to support this intervention choice. |

Part Six: Overall Assessment

Variance of protest effectiveness

Since protests vary widely in their implementation, they probably also vary widely in their effectiveness. In the course of our research, we’ve compiled some provisional advice for organizing particularly effective protests:

To maximize the positive effects and minimize the negative effects that protests have on public opinion, activists should consider the following:

- Consider combining protests with other interventions, like leafleting, to allow protesters to better engage with witnesses.69

- Take a compassionate, rather than a “shaming” tone at protests, and target institutions rather than individuals.70

- Contact the press to notify them of the protest and follow up with them afterwards.71

- Have at least one person present at each protest who is prepared to speak with the target of the protest and/or the press.72

- Because visually impressive protests are more likely to gain press coverage, consider the backdrop, signs, and attire of activists.73

To maximize the positive effects and minimize the negative effects that protests have on the movement’s capacity, activists should consider the following:

- Try to ensure that protesters leave each protest feeling inspired rather than defeated.74 Tausch & Becker (2012) found that anger at a failed protest and pride in a successful protest both predict intentions to continue protesting.

- Recruit a large and diverse community of activists. Chenoweth & Stephan (2011) argue that the diversity of activists leads to the diversity of tactics, which increases the likelihood of a movement’s success.75

- Because some types of protests can pose a higher risk for protesters who have relatively marginalized identities, organizers should:

- Understand and communicate the risks of protests to all activists

- Consider recruiting protesters who have relatively privileged identities to engage in riskier activities, such as protesting76

- Ensure that there are safe ways for activists to participate if they can’t or don’t want to protest

To maximize the positive effects and minimize the negative effects that protests have on industry, activists should consider the following:

- Protests seem to be most effective when used in conjunction with other interventions, like petitions, phone calls, and email campaigns77

- Protests and other activist challenges to corporations are likely more successful when repeated (both within a given campaign and in subsequent campaigns) at the same corporation (Chenoweth & Olsen, 2016)

- Corporations undergoing leadership changes are more susceptible to activist challenges (Chenoweth & Olsen, 2016).

To maximize the positive effects and minimize the negative effects that protests have on the movement’s alliances, activists should consider the following:

- We believe that the animal advocacy movement would benefit from building stronger coalitions with other social justice movements. Much of our general advice about supporting other movements is highly relevant for protesters. (For example: “Do not advocate for your issue in ways that are racist, sexist, heterosexist, cissexist, sizeist, ableist, ageist, classist, etc.”)

- Consider attending protests for consonant movements and advocating for animals as well as other the other issues represented there.78 However, be careful not to do so in a way that detracts, or could appear to detract, from the primary goals of the protest.79

To maximize the positive effects and minimize the negative effects that protests have on policy and law, activists should consider the following:

- Protests are more likely to influence policy when they have high public support and powerful alliances (Giugni & Yamasaki, 2009; Chenoweth & Stephan, 2011).

Evaluative questions80

| Discussion:

In the short term, protests achieve both positive and negative outcomes. They can garner positive or negative attention from their targets, witnesses, and the media. They can mobilize some activists but alienate others. They can prompt key influencers to become allies or opponents of the animal advocacy movement. None of these outcomes directly affect animals. In the longer term, we believe that the effects of protests will be net positive for animals. Protests have already played a role in convincing some corporations to make concessions, and there is some evidence that, by using protests, activists can advance their cause on the nation’s political agenda. By visibly asserting their uncompromising position, protesters might also create a shift in social norms that will benefit animals. Since protests cause change over the long term, we have substantial uncertainty about many of their outcomes. Moreover, since protests interact with many other animal advocacy interventions, it’s difficult to determine how much responsibility they bear for the change that they seem to produce. For example, protests may favorably influence public opinion in conjunction with education and other interventions, but not alone. Even if protests are not a particularly effective intervention on their own, we think that there are some compelling arguments that protests are a necessary component of successful social movements. |

||||

| Scale: | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| This intervention creates no net positive change (and might even create net negative change) for animals. | This intervention creates some net positive change for animals. | This intervention creates significant net positive change for animals. | ||

| Level of Certainty: | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| We are highly uncertain about the impact this intervention has for animals. | We are moderately certain about the impact this intervention has for animals. | We are highly certain about the impact this intervention has for animals. | ||

| Discussion:

There is some evidence for each of the mechanisms represented in our theory of change, as described in Part Two of this report. However, much of the evidence comes from studies with important limitations and may not be generalizable to animal advocacy protests. Many of the studies do not directly investigate the impact of protests; rather, they investigate the impact of civil resistance, direct action, or other more general approaches. Most of them investigate social movements other than the animal advocacy movement. The animal movement seems relevantly different from many other movements, particularly those that are closely associated with major political parties or those with which large portions of the population identify. The uncertain generalizability of much of the relevant evidence limits the extent to which it supports our theory of change. |

||||

| Scale: | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |