The Humane League

Archived Review| Review Published: | December, 2019 |

| Current Version | 2023 |

Archived Version: December, 2019

What does The Humane League do?

The Humane League (THL)’s mission is to end the abuse of animals raised for food. THL engages in a variety of programs designed to persuade individuals and organizations to adopt behaviors that reduce farmed animal suffering. They are headquartered in the U.S. but they operate globally, with a team based in Japan as well as independent charities in the U.K. and Mexico. THL’s largest programs, based on their budget, are their corporate campaigns and grassroots organizing. They encourage corporations to enact policies dictating higher animal welfare standards and they educate the public using outreach materials such as humane education presentations and online videos. Through their grassroots offices and campus leadership program, they recruit and train new animal advocates. THL also works to build the animal advocacy movement internationally through the Open Wing Alliance (OWA), a global coalition founded by THL whose mission is to end battery cages globally. The OWA offers funding and training to advocacy groups interested in working on corporate campaigns.

What are their strengths?

We view THL as a leader in the animal advocacy movement and a good model for many other organizations. THL makes particularly strong efforts to assess their own programs and to look for and test ways to improve them. Their success in their corporate campaigns and the publication of their research through Humane League Labs (HLL) has shifted the outlook and programming of several other advocacy organizations toward finding the best ways to advocate for animals.

THL’s organizational structure appears to be strong, with a cohesive and democratic culture promoting positive relationships between THL staff, board members, and volunteers. This is especially important for THL because part of the intention of their local offices is to build a grassroots movement, and setting a positive and results-oriented tone for those new to the movement is good for animal advocacy as a whole. THL’s track record demonstrates significant success. Recently, they’ve been especially successful with their corporate campaigns, and they seem to have played an important role in promoting corporate campaigns outside of the U.S. by training and collaborating with other groups through the OWA.

What are their weaknesses?

We are somewhat concerned about THL’s sustained high rate of expansion. In the past, THL has been remarkably quick to expand in response to increased funding. So far, they have been able to use large amounts of new funding efficiently, but we believe there’s a chance that they’re reaching a size where significant changes in organization or internal systems are required, which might slow their growth. They have already identified the wide international distribution of their team as a challenge, and are working on improving the efficiency of their internal communications and project management. For instance, they engaged in a large re-organization and changed many of their internal systems over the past year.

Why did The Humane League receive our top recommendation?

THL has an exceptionally strong commitment to using studies and systematic data collection to guide their approach to advocacy. Their corporate campaigns are especially strong, and they often take the lead in collaborating with other groups to facilitate knowledge-sharing about their strategic approach. They have been flexible in using their grassroots network for a variety of advocacy efforts—including individual outreach, support for corporate campaigns, and grassroots legislative advocacy. We find THL to be an excellent giving opportunity because of their strong programs and evidence-driven outlook.

How much money could they use?

THL’s plans for expansion are expected to cost between $1.1 million and $4.6 million. This number does not take into account potential increases or decreases in revenue. In addition, THL could use an additional $400,000 to $2.0 million for grants via the Open Wing Alliance. We expect they would use additional funding to expand their teams in the U.S., Mexico, and the U.K., to support THL Japan, and to increase salaries and benefits.

What do you get for your donation?

From an average $1,000 donation, THL would spend about $507 on corporate outreach; $395 on capacity building through volunteer recruitment, training, and OWA training and grants; and $97 on individual outreach.

We don’t know exactly what THL will do if they raise additional funds beyond what they’ve budgeted for this year, but we think additional marginal funds will be used similarly to existing funds.

The Humane League has been one of our Top Charities since August 2012.

Table of Contents

- How The Humane League Performs on our Criteria

- Interpreting our “Overall Assessments”

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Questions for Further Consideration

- Supplemental Materials

How The Humane League Performs on our Criteria

Interpreting our “Overall Assessments”

We provide an overall assessment of each charity’s performance on each criterion. These assessments are expressed as two series of circles. The number of teal circles represents our assessment of a charity’s performance on a given criterion relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated.

| A single circle indicates that a charity’s performance is weak on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated: | |

| Two circles indicate that a charity’s performance is average on a given criterion, relative to other charities we’ve evaluated: | |

| Three circles indicate that a charity’s performance is strong on a given criterion, relative to the other charities we’ve evaluated: |

The number of gray circles indicates the strength of the evidence supporting each performance assessment and, correspondingly, our confidence in each assessment:

| Low confidence: Very limited evidence is available pertaining to the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to other charities. The evidence that is available may be low quality or difficult to verify. | |

| Moderate confidence: There is evidence supporting our conclusion, and at least some of it is high quality and/or verified with third-party sources. | |

| High confidence: There is substantial high-quality evidence supporting the charity’s performance on this criterion, relative to other charities. There may be randomized controlled trials supporting the effectiveness of the charity’s programs and/or multiple third-party sources confirming the charity’s accomplishments.1 |

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Overall Assessment:

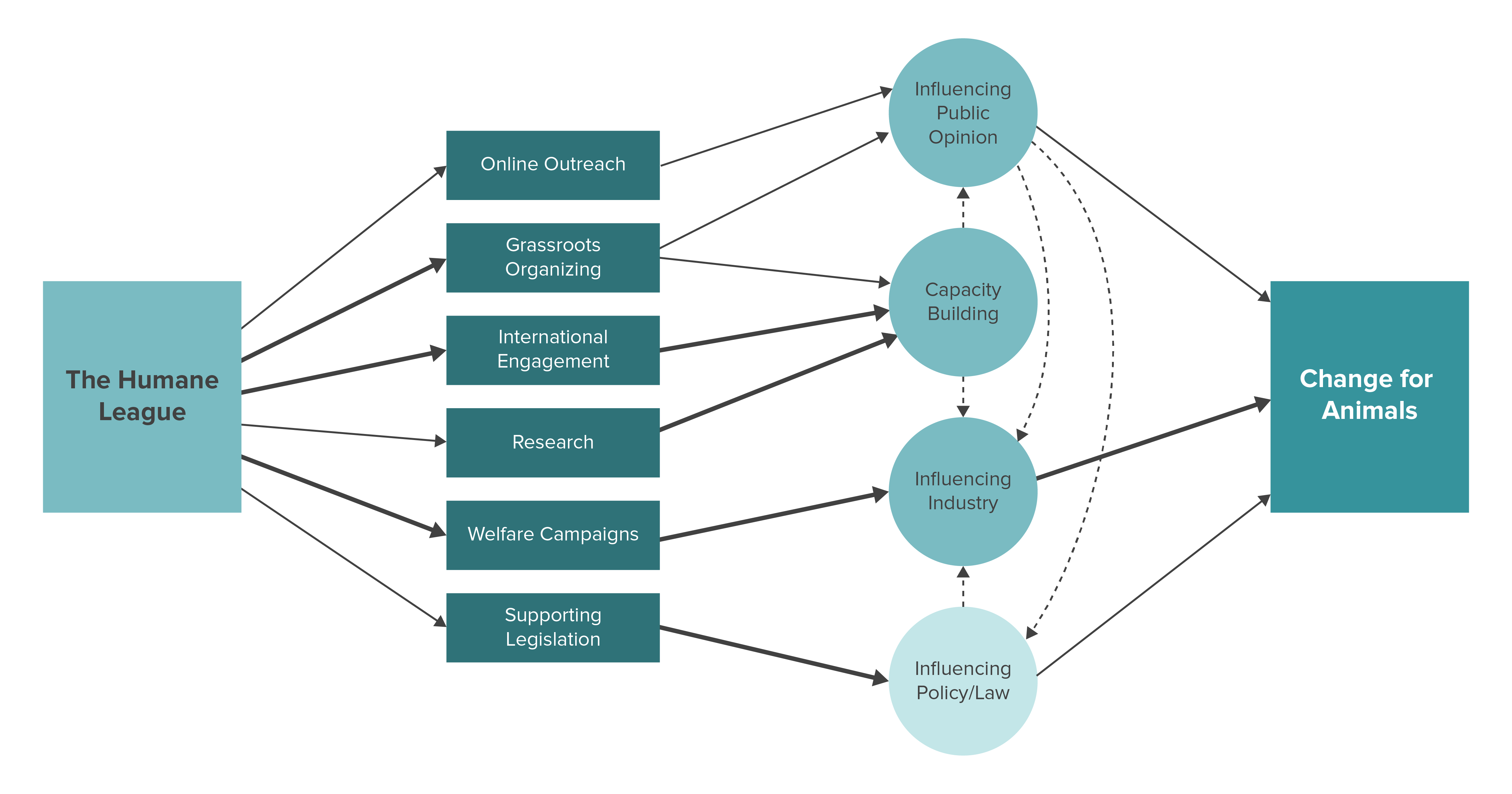

When we begin our evaluation process, we consider whether each charity is working in high-impact cause areas and employing effective interventions that are likely to produce positive outcomes for animals. These outcomes tend to fall under at least one of the categories described in our Menu of Outcomes for Animal Advocacy. These categories are influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

Cause Areas

The Humane League focuses primarily on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we believe is a high-impact cause area.

Theory of Change

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

A note about long-term impact

We do represent some of each charity’s long-term impact in our theory of change diagrams, though we are generally much less certain about the long-term impact of a charity or intervention than we are about more short-term impact. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) may skew toward overemphasizing short-term impact. Nevertheless, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most. The potential number of individuals affected increases over time due to both human and animal population growth as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Interventions and Projected Outcomes

THL pursues many different avenues for creating change for animals: They work to influence public opinion, build the capacity of the movement, influence industry, and influence policy and the law. Below, we describe the work that they do in each area, listed roughly in order of the financial resources they devote to each area (from highest to lowest).

Influencing industry

THL works with corporations to adopt better animal welfare policies and ban particularly cruel practices in the animal agriculture industry. In the short to medium term, corporate outreach can create change for a larger number of animals than individual outreach can with the same amount of resources. It also seems more tractable to secure systemic change one corporation at a time, rather than lobbying for larger-scale legislative change. Though the long-term effects of corporate outreach are yet to be seen, we believe that these interventions have a high potential to be impactful when implemented thoughtfully.

THL works to get corporations to implement welfare reforms through large, nationwide, or global pressure campaigns. They use their large grassroots network of volunteers and staff to apply coordinated pressure through protests, media, and petitions against food companies that purchase animal products from producers that raise animals in particularly cruel conditions. THL also works around the world to achieve cage-free commitments and has been successful with some of the largest food companies in the U.S., the U.K., Japan, and Latin America.2 Through the OWA and in collaboration with other advocacy groups around the world, they have helped achieve cage-free commitments in more countries than one charity could feasibly operate.3

THL is currently involved in cage-free egg campaigns in the U.K., Mexico, and Japan. THL has also been involved in several global cage-free campaigns in the last year. Cage-free egg systems are believed to reduce hen suffering by increasing the space available to hens and providing them important behavioral opportunities, although during the transition process mortality may increase, and there is some risk it may remain elevated.4 In the U.S. and the U.K., THL is campaigning for companies to switch to higher welfare (but likely slower growing) breeds of broiler chickens, and to commit to provisions on stocking density, lighting, and environmental enrichments. Such commitments may lead to higher welfare but also to more animal days lived in factory farms.

Influencing public opinion

THL works to influence individuals to adopt more animal-friendly attitudes and behaviors through media outreach, online outreach, and grassroots activism. The effects of public outreach are particularly difficult to measure for at least two important reasons. First, most studies of the effects of public outreach rely on self-reported data, which is generally unreliable.5 Second, even if we understood the effects of public outreach on individual behavior, we still know very little about how animals are impacted by behaviors such as individuals changing their diets, deciding to vote for animal-friendly laws, or becoming activists. Despite the uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of most public outreach interventions, we do think it’s important for the animal advocacy movement to target at least some outreach toward individuals. A shift in public attitudes and consumer preferences could help drive industry changes and lead to greater support for more animal-friendly policies; in fact, it might be a necessary precursor to more systemic change. On the whole, however, we believe that efforts to influence public opinion are much less neglected than other types of interventions, as we describe in our Allocation of Movement Resources report.

Much of THL’s work on influencing public opinion is in support of its corporate campaigns. They put pressure on industry to encourage companies to make cage-free egg and broiler chicken welfare commitments. Their tactics vary depending on the context, but include ad campaigns, media outreach, social media, protests, leafleting, and petitions. We believe that negative publicity may make companies more likely to make and keep animal welfare commitments. It is likely that these efforts also raise awareness of animal advocacy and conditions on farms more generally.

In the U.S. and the U.K., THL also puts some resources into individual outreach, encouraging people to reduce or eliminate their consumption of animal products. They run online ads and recruit people for vegetarian pledges. We are uncertain of the effect of online outreach and are concerned that the marginal impact may be fairly low, as people may not engage with the content very deeply. We believe that leafleting is likely less cost effective than other forms of animal advocacy at creating short-term impact. However, while our 2017 Leafleting Intervention Report failed to find compelling randomized controlled trial evidence for its short-term impact, leafleting may still serve other, more long-term purposes—such as general awareness-raising, contributing to gradual changes in perspective and habits,6 and providing an easy way for some people to get involved in animal activism. Vegan pledge programs are likely to recruit new people to the movement, normalize veganism, and raise awareness of veganism and animal-related issues. However, many participants are likely to return to eating animal products afterward.7

Capacity building

Working to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement can have far-reaching impact. While capacity-building projects may not always help animals directly, they can help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Our recent research on the way that resources are allocated between different animal advocacy interventions suggests that capacity building is currently neglected relative to other outcomes such as influencing public opinion and industry. THL engages in movement coordination and activist trainings and recruitment, all of which are forms of capacity building.

THL works to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement internationally as well as in the U.S. They share their knowledge and experience with other groups to improve corporate outreach strategy abroad, particularly through the Open Wing Alliance (OWA), which they founded. In addition to sharing strategy and offering training, THL also helps to fund OWA member organizations around the world through a grant program.8 They also launched chickenwatch.org, which helps the movement track cage-free and broiler welfare commitments and their effects.9

Another way in which THL builds the capacity of the movement is by recruiting, mobilizing, and training activists. Through outreach events, education, protests, and work parties, THL works to help build effective animal advocacy skills among activists to strengthen the capacity of the movement.10 THL also trains and supports volunteer grassroots advocates, particularly students.11 A team of field organizers oversees both students and non-student volunteers; by giving volunteers autonomy and having them take leadership roles, THL expands their reach and allows volunteers to develop their capabilities as activists. THL has also organized a coalition of U.S. animal rights clubs, the Student Alliance for Animals, similar in concept to the Open Wing Alliance.

Influencing policy and the law

THL engages in grassroots legislative advocacy. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects to be long-lasting. We believe that encoding protections for animals into the law is a key component of creating a society that is just and caring toward animals.

THL was involved in signature-gathering and get-out-the-vote efforts which led to the passage of California’s Proposition 12. We think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to have an impact on a large number of animals, and are more likely to be followed through on than similar corporate campaigns.

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

Overall Assessment:

We look to recommend charities that are not just high impact, but also have room to grow. Since a recommendation from us can lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding, we look for evidence that the charity will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. We consider whether there are any non-monetary barriers to the charity’s growth, such as time or talent shortages. To do this, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. We also consider the charity’s existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential areas for growth and expansion.

Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for funding more quickly than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. We check in with each of our Top Charities mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented below to indicate whether we still expect them to effectively absorb additional funding at that point.

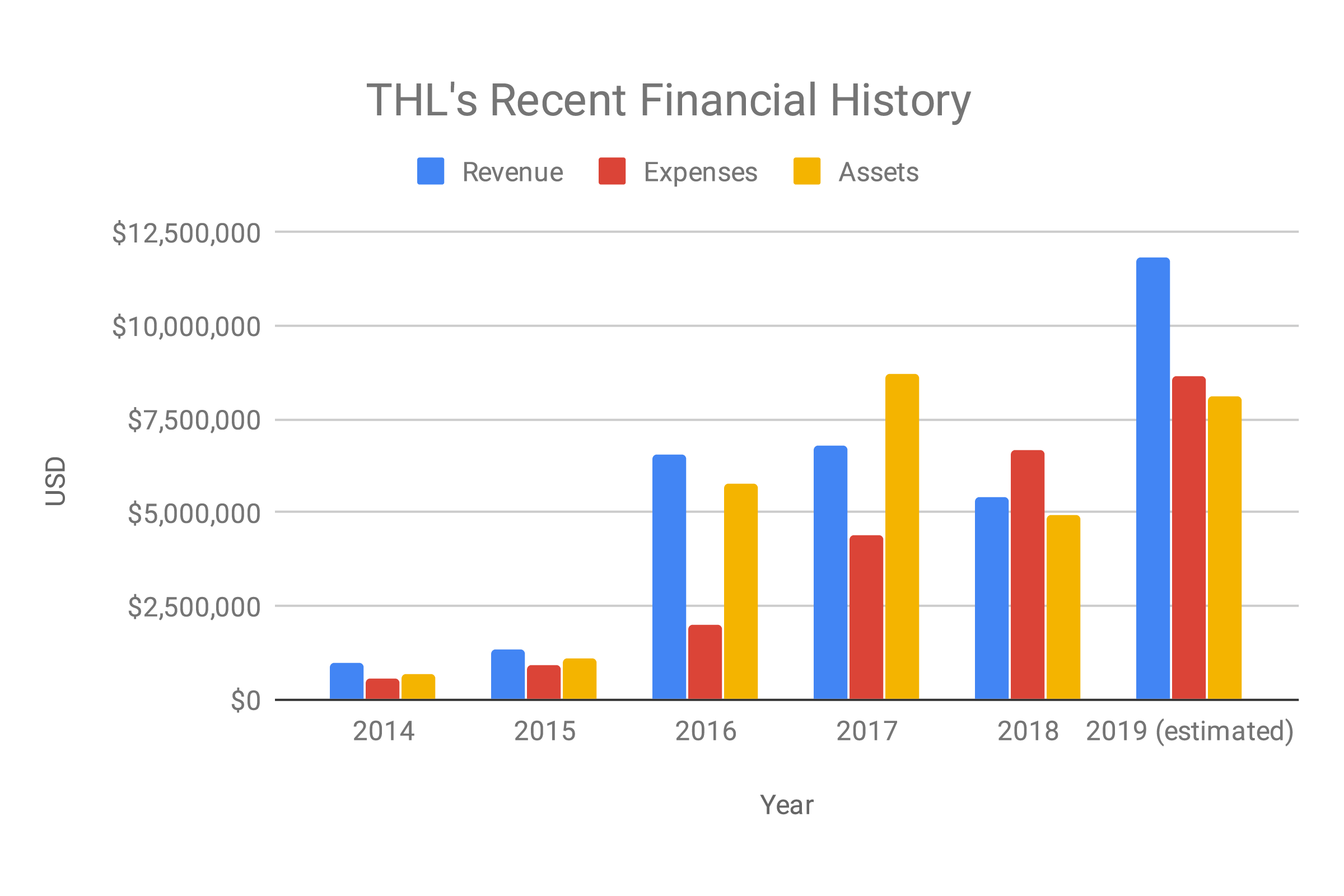

Recent Financial History

The following chart shows THL’s recent revenue, assets,12 and expenses.13, 14 In this chart, the 2019 revenue and expenses are estimated based on the financials of the first six months of 2019.15 Note that the variation in revenue in this graph is a result of the fact that large, multi-year grants are logged in the year they are confirmed and not in the multiple years when they are disbursed.16 THL notes they are cognizant that a majority of their funding comes from two major donors. They are making an effort to diversify their revenue sources via investing in direct mail, online, and planned giving.17

Estimated Future Expenses

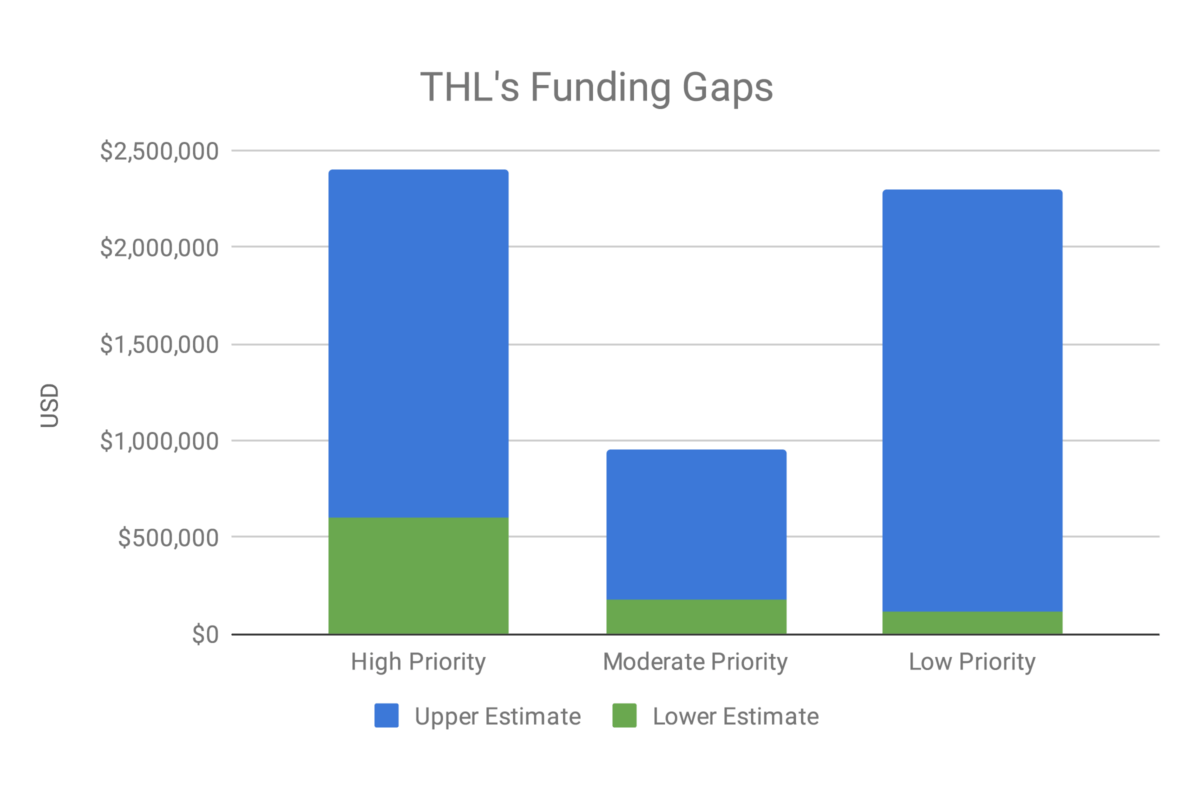

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area likely varies in its cost-effectiveness. In order to evaluate room for more funding over three priority levels, we consider each charity’s estimated future expenses,18 our assessment of the effectiveness19 of each future expense, and the feasibility of meeting each expense if more funding were provided.20

| Estimated future expense | Funding estimate | Priority level |

| Hiring 9.5 to 15 new staff in the U.S.21 | $0.33M to $1.8M22 | High (62%) and moderate (38%) |

| Hiring 4.7 to 7.5 new staff members in Mexico | $0.68M to $0.39M23 | High (62%) and moderate (38%) |

| Hiring 4.7 to 7.5 new staff members in the U.K. | $0.18M to $0.94M24 | High (62%) and moderate (38%) |

| Awarding OWA grants25 | $0.4M to $2.0M | High |

| Supporting THL Japan26 | $5.7k to $98k | High |

| Increasing salaries and benefits27 | $0.10M to 0.31M28 | High |

| Possible additional expenses29 | $0.11M to $2.7M | Low |

Estimated Room for More Funding

The cost of THL’s plans for expansion over the three priority levels is estimated via Guesstimate and visualized in the chart above. The cost for their expansion is expected to be between $1.1M and $4.6M.30 Our room for more funding estimates include a linear projection of the charity’s revenue from previous years to predict the amount by which we expect the revenue to increase or decrease in the next year. THL has received funding influenced by ACE as a result of its prior Top Charity status, and in order to more accurately estimate their room for more funding, we have subtracted the estimated ACE-influenced funding from our estimates of future revenue, which means the charity’s real 2020 revenue could be higher than the revenue we predict.31 Comparing THL’s estimated revenue for 201932 and 2020,33 this model predicts that in the next year, THL’s revenue will change between -$4.1M to $0.52M. As mentioned, these estimates can be lower than expected because we have not included ACE-influenced revenue so as to account for our own impact. The estimates for change of revenue are more uncertain than the estimated costs of expected expansion, so we put limited weight on them in our analysis and put more weight on our estimate for cost of expansion.34 In addition, THL could use an additional $0.40M to $2.0M for grants via the OWA.35

Criterion 3: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

Overall Assessment:

Information about a charity’s track record can help us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments, which is information that cannot always be incorporated into our other criteria. An organization’s track record is sometimes a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences between two charities.

In this section, we consider whether each charity’s programs have been well executed in the past by evaluating some of the key results that they have accomplished. Often, these outcomes are reported to us by the charities and we are not able to corroborate their reports.36 We do not expect charities to fabricate accomplishments, but we do think it’s important to be transparent about which outcomes are reported to us and which we have corroborated or identified independently. The following outcomes were reported to us unless indicated otherwise.

THL was founded in 2005 with their Public Awareness Campaigns, Movement Building, and Veg Advocacy programs. In 2015, they launched their Corporate Outreach program. Below is our assessment of each of these programs, ordered according to the expenses invested in each one (from highest to lowest) in 2018–2019:

Program Duration

2005–present (Public Awareness Campaigns), 2015–present (Corporate Outreach)37

Key Results38

- Achieved at least 400 cage-free and 100 broiler welfare corporate commitments39 (2005 to mid-2019)

- Supported the passage of Prop 12 in California (2018)

- Supported the Question 3 initiative in Massachusetts (2016)

- Achieved a commitment from the United Egg Producers (UEP) to eliminate the culling of male chicks (2016)

Our Assessment

THL has a strong track record of success with their public awareness campaigns, especially with regards to achieving corporate cage-free and broiler welfare commitments (both in the U.S. and internationally).40 In 2015, they launched their Corporate Outreach program which aims to secure commitments by building relationships with corporations. In 2016, they achieved a commitment from the UEP to eliminate the culling of male chicks, which could spare a large number of chickens if implemented.

Through the OWA, which they launched in 2016, THL’s campaigns have achieved about four cage-free commitments from major international companies per year, as well as many minor commitments from companies around the world.41 Note that many of THL’s corporate victories have been achieved in collaboration with other organizations,42 which makes it difficult to determine the impact of these programs. However, even if just a small percentage of the commitments are implemented, they could affect millions of chickens per year.43

THL has also campaigned for successful legislative initiatives. In 2016, they supported the Question 3 initiative in Massachusetts against extreme forms of farmed animal confinement. In 2018, they campaigned for Proposition 12 in California,44 which will affect many millions of farmed animals per year when it comes into force.45 It’s worth noting that most of these victories have been achieved in cooperation with many others, so it is difficult to determine the extent of THL’s contribution.

Program Duration

2005–present

Key Results46

- Organized about 14 training events targeting OWA members, distributed several grants to OWA groups, recruited 16 new OWA members, and provided personalized training to ten OWA groups (2018–2019)

- Conducted webinars and online training sessions to students and volunteers on corporate campaigning and animal advocacy47 (2018–2019)

- Provided leadership trainings, developed a student handbook and a program curriculum for their U.S. campus program (2018)

- Launched a fellowship program, launched the Student Alliance for Animals, and restructured their grassroots program (2019)

- Launched chickenwatch.org to track cage-free and broiler welfare commitments (2018–2019)

Our Assessment

In late 2016, THL launched the OWA. Since 2017, they have hosted an annual Global Summit as well as several regional summits and training events. In two years, the number of grants they issue to member organizations has substantially increased.48 Additionally, new member organizations have joined the coalition which now accounts for more than 60 members around the world, mostly in Europe.49 OWA grantees achieved more than 80 corporate commitments in 2018 and a similar number in the first six months of 2019.50 If implemented, these commitments could affect a large number of egg-laying hens. In addition, THL launched the website chickenwatch.org in order to help the movement track cage-free and broiler commitments.

THL’s capacity-building activities through the OWA have likely strengthened the animal advocacy movement, probably contributing to accelerated cage-free corporate commitments around the world. Although THL’s contribution to these victories is mostly indirect, the fact that THL is directly responsible for the creation and coordination of the OWA implies that without their organizational capability and experience in campaigning, the OWA would likely not have seen the success it has.

THL has engaged in grassroots outreach for several years, particularly on U.S. college campuses by working with campus organizers and student interns, providing training materials, organizing events, and mobilizing students.51 THL reports that in order to increase their impact, in 2019 they started to restructure their U.S. campus program by launching two programs instead: a fellowship program and the Student Alliance for Animals. THL also reports restructuring their grassroots program, which consists of training volunteers and online activists in the U.S and internationally through webinars and online training sessions. Although we are highly uncertain about the effectiveness of this program, it could have contributed to building the farmed animal advocacy movement.

Program Duration

2005–present

Key Results52

- Distributed almost 2 million online Veg Starter Guides/Cookbooks53 (2018–2019)

- Achieved over 40 million views on webpages with footage of factory farms54 (2018–2019)

Our Assessment

THL has increased the number of online Veg Starter Guides and cookbooks they distribute, reporting over 1 million in 2017 and almost 2 million distributed in 2018–2019. They have also increased the number of views of factory farm footage from over 36 million in 2017 to over 41 million in 2018–2019.55 Although we are highly uncertain about the extent to which THL’s online outreach has impacted animals, it is likely that their resources may have somewhat affected public attitudes and behaviors toward farmed animals, including dietary change.

Criterion 4: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

Overall Assessment:

A charity’s recent cost-effectiveness provides an insight into how well it has made use of its available resources and is a useful component to understanding how cost-effective future donations to the charity might be. In this criterion, we take a more in-depth look at the charity’s use of resources and compare that to the outcomes they have achieved in each of their main programs.

This year, we have used an approach in which we more qualitatively analyze a charity’s costs and outcomes. In particular, we have focused on the cost-effectiveness of the charity’s specific implementation of each of its programs in comparison to similar programs conducted by other charities we are reviewing this year. We have categorized the charity’s programs into different intervention types and compared the charity’s outcomes and expenditures from January 2018 to June 2019 to other charities we have reviewed in our 2019 evaluations. To facilitate comparisons, we have also compiled spreadsheets of all reviewed charities’ expenditures and outcomes by intervention type.56

Analyzing cost-effectiveness carries some risks by incentivizing behaviors that, on the whole, we do not think are valuable for the movement.57 Particular to the following analysis, we are somewhat concerned about our inclusion of staff time and volunteer time. Focusing on staff time as an indicator of cost-effectiveness can reward charities that underpay their staff, and discourage organizations from working toward increasing salaries to be more in line with the for-profit sector. As for volunteer time, we think that volunteer programs can increase the cost-effectiveness of a charity’s work, however, overreliance on volunteers can make a charity’s work less sustainable. While we think that these factors are relevant and worth including in our analysis of cost-effectiveness, we encourage readers to bear these concerns in mind while reading this criterion.

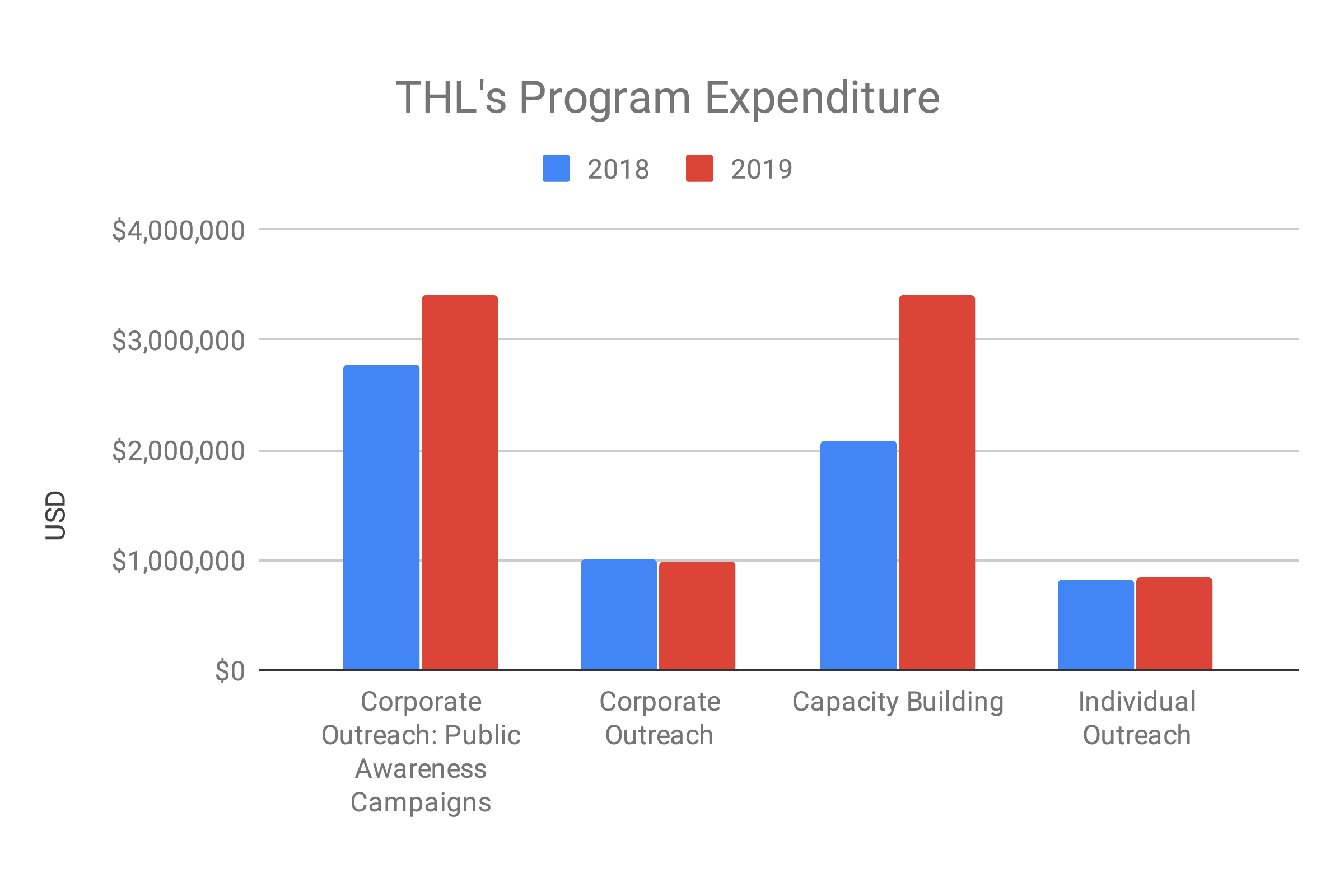

Overview of Expenditures

The following chart shows THL’s program expenditures in 2018 and 2019.58

We asked THL to provide us with their expenditures for their top 3–5 programs as well as their total expenditures. The estimates provided in the graph were calculated by dividing up their total expenditures proportionately, according to the size of their programs. This allowed us to incorporate their general organizational running costs into our consideration of their cost-effectiveness.

Corporate Outreach

Summary of outcomes: secured 23 cage-free commitments in Japan, 27 cage-free commitments in the U.K, 9 cage-free commitments in the E.U., 6 global cage-free commitments, 26 broiler commitments in the U.S., 4 broiler commitments in the U.K., 7 broiler commitments in the E.U., and 4 additional global cage-free commitments; made progress on the McDonald’s campaign; and garnered support for the passage of Proposition 12. For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in corporate outreach.

Use of resources

Table 1: Estimated resource usage in THL’s corporate outreach, Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Resources | THL’s Corporate Outreach | THL’s Public Awareness Campaigns | Average across all reviewed charities59 |

| Expenditures60 (USD) | $1,500,000 | $4,500,000 | $1,200,000 |

| Staff time (weeks61) | 507 | 1803 | 380 |

| Volunteer time (weeks62) | 0 | Unknown | 0 |

THL spent more than average on corporate campaigns compared to the other charities we reviewed this year. Relative to their expenditures for this program, their staff time is roughly equal to the average of other charities we reviewed.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

Table 2: Estimated number of animals affected by corporate commitments, Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Number affected per year by commitments (Corporate Outreach)63 | Number affected per year by commitments (Public Awareness Campaigns”)64 | Average across reviewed charities65, 66 | |

| Caged hens | 9.5M–30M | 0.2M–4.8M | 4M–10M |

| Broiler chickens | 51M–140M | 0 | 22M–35M |

Corporate outreach that is focused on securing commitments to improve welfare has a direct impact on animals. After factoring in the proportional responsibility that THL had for each commitment, we can estimate how many animals will be affected when the commitments are implemented.67 Overall, after accounting for expenditures, THL’s Corporate Outreach program appears to be much more cost effective than their Public Awareness Campaigns program. However, it is not clear to what extent the work in these programs is overlapping. Taking both programs’ expenditures and outcomes together, their work appears to be close to the average cost-effectiveness of the charities we have reviewed this year. This estimate has limitations in that the ranges are often very uncertain, and it does not account for other activities that charities engage in as part of their corporate outreach programs.

As part of their Public Awareness Campaigns program, they have continued their work on the McDonald’s campaign; for example, they launched an ad campaign that resulted in 35 media mentions. THL is one of six organizations leading the broiler welfare campaign against McDonald’s, which, if successful, would impact an estimated 200 million to 340 million chickens annually.

Some of their reported outcomes, while having large impacts for animals, were conducted in conjunction with several other groups, so their responsibility for the outcome is not always clear. For example, in the Proposition 12 campaign, they were one of 33 organizations listed in support of the proposition, and it seems likely that its success is mostly attributable to substantial funding from the Humane Society of the United States and the Open Philanthropy Action Fund.68 Similarly, the global corporate commitments secured with the OWA were achieved in conjunction with some of the 65 OWA members. However, as THL founded the alliance and coordinated many of the campaigns, it is likely that they are more responsible for its successes than other groups.

Capacity Building/Building Alliances

Summary of outcomes: recruited 16 new members to the OWA; launched chickenwatch.org; provided training to ten OWA members; conducted training webinars for ~400 activists; made various improvements to their student outreach program; restructured their grassroots organizing program; launched the Student Alliance for Animals; launched a fellowship program; and engaged in movement building in Mexico and the U.K. For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in capacity building/building alliances.

Use of resources

Table 3: Estimated resource usage in THL’s capacity building, Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Resources | THL | Average across all reviewed charities69 |

| Expenditures70 (USD) | $3,800,000 | $1,400,000 |

| Staff time (weeks71) | 1,255 | 316 |

| Volunteer time (weeks72) | Unknown | 55 |

THL’s expenditures and staff time were both larger than the average of other charities we reviewed. They were roughly proportional in size to the average.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

Capacity building encompasses a broad category of outcomes for animals that are typically indirect, and as such it is difficult to make an assessment of their cost-effectiveness. As a large and well-established organization, THL seems well-positioned to take on opportunities that are not available to smaller organizations. For example, they work through the OWA to coordinate corporate campaigns against international companies. The OWA builds the capacity of the movement by recruiting new members and providing training to existing members. This strategy of sharing knowledge allows THL’s successful corporate campaigning model to be spread internationally without the need for their own expansion, and it seems to be particularly cost-effective.

Most of their other achievements are focused on building the capacity of students and grassroots activists, both through training, the launch of a fellowship program, and the Student Alliance for Animals (which is modeled on the OWA). Along with the restructuring of their student outreach program, most of these outcomes are in their early stages, and as such, the cost-effectiveness of these programs seems likely to improve in the future. After accounting for all their outcomes and expenditures, THL’s capacity building/building alliances seems close to the average cost-effectiveness of other reviewed charities in 2019.

Individual Outreach

Summary of outcomes: distributed ~2 million veg starter guides online and received 41 million+ visits to web pages featuring footage of animals suffering in factory farms. For more information, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in corporate outreach.

Use of resources

Table 4: Estimated resource usage in THL’s individual outreach, Jan ’18–Jun ’19

| Resources | THL | Average across all reviewed charities73 |

| Expenditures74 (USD) | $1,200,000 | $370,000 |

| Staff time (weeks75) | 167 | 186 |

| Volunteer time (weeks76) | 0 | 727 |

Relative to their expenditures for this program, THL’s staff time is much lower than the average of charities we reviewed this year.

Evaluation of outcome cost-effectiveness

Individual outreach primarily creates impact by inducing behavior changes in the individuals receiving the intervention. THL conducts their individual advocacy through online ads, directing people to both factory farming footage and vegan starter guides. The scalability of online ads means that large audiences can be reached for comparatively small amounts of funding, but we think it’s likely that information provided online is less impactful than through an equivalent in-person interaction. THL notes that their funding for this program is provided through restricted funding, and it seems that they would not continue the program in the same way if the funding were unrestricted,77 which may indicate that they don’t believe it to be as cost effective as their other programs.

Of the charities we reviewed in 2019, THL is the only one that reported an individual outreach program that is primarily focused on online ads, so it is difficult to make an overall comparison. That said, THL appears to have achieved a large reach when factoring in their average amount of expenditures, indicating that their individual outreach may be more cost effective than that of other reviewed charities in 2019.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

Overall Assessment:

By conducting reliable self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs and modify or discontinue less successful programs. When such systems of improvement work well, all stakeholders benefit: Leadership is able to refine their strategy, staff better understand the purpose of their work, and donors can be more confident in the impact of their donations.

In this section, we consider how the charity has assessed its programs in the past. We then examine the extent to which the charity has updated their programs in light of past assessments.

How does the charity identify areas of success and failure?

Most of THL’s teams conduct a generic debrief after each project by using a debrief template and having a meeting where they discuss what went well, what did not, why, and what they could do differently in the future.78 Every staff member has goals with built-in metrics, even when the goals are qualitative. However, THL reports that their teams are not consistent enough at measuring the outcomes of projects, which is why they intend to focus on training staff in project management in the next year.79

THL has consulted with external advisors to redefine their organizing structure and roles, as well as to improve their internal structure and growth, their development, and fundraising capacities.80

Does the charity respond appropriately to identified areas of success and failure?

We believe that THL has responded appropriately to their self-determined areas of success and failure in many ways. We list three salient examples below.

- THL recognizes that most of their biggest wins have come from working simultaneously with dozens of organizations on different campaigns, making the OWA one of their most successful initiatives in the last few years.81 Based on this success, THL has directed more resources toward the OWA, expanding their membership, training, and grants over the years. THL also continues to take a collaborative approach to developing other campaigns and programs, and they are making efforts to facilitate alliances and build a strong farmed animal advocacy movement.

- THL reports that as an internationally distributed team, they face challenges with project management, effective communication, and other challenges associated with remote work.82 Although this system allows them to have an international impact and influence across many cultures, it also comes with project management challenges that THL has been trying to address in different ways. Notably, they have recently carried out a general reorganization to improve meeting structure and internal processes. As part of the reorganization, they changed their leadership team to no longer be composed of senior U.S. staff—now, it is a more international team with leaders from numerous countries.83 This reorganization process seems to be a promising strategy to facilitate general management and communication between teams in different countries.

- In order to improve the effectiveness of their grassroots work, THL has recently reorganized their programs. They modified their campus outreach program in the U.S. by launching two programs instead: a fellowship program and the Student Alliance for Animals.84 Until 2019, THL was hiring students to provide them with one-on-one mentorship and training. The strategy was to educate students who would then share their knowledge with their respective student clubs. THL realized, however, that their impact on those clubs did not go beyond the academic school year due to turnover among club members. To address this issue, they decided to continue the one-on-one mentorship with their (paid) fellowship program and launched the Student Alliance for Animals, which rather than recruiting individuals, recruits student clubs (similar to the OWA model).85 Students engaged in the Student Alliance for Animals also receive one-on-one mentorship from THL’s Field Organizing Team.86 Although the results of the student alliance are yet to be seen, it seems to be a sustainable intervention to engage students at college and university campuses because it creates affiliations with student clubs rather than individuals, securing the continuity of the program.

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

Overall Assessment:

Strongly-led charities are likely to be more successful at responding to internal and external challenges and at reaching their goals. In this section, we describe each charity’s key leadership and assess some of their strengths and weaknesses.

Part of a leader’s job is to develop and guide the strategic vision of the organization. Given our commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we look for charities whose strategy is aligned with that goal. We also believe that a well-developed strategic vision should include feasible goals. Since a well-developed strategic vision is likely the result of well-run strategic planning, we consider each charity’s planning process in this section.

Key Leadership

Leadership staff

David Coman-Hidy has been the president of THL since 2012 and has overseen its significant expansion in the U.S. and internationally. Our impression is that Coman-Hidy is a capable leader and that he has surrounded himself with equally capable colleagues, such as Executive Vice President Andrea Gunn.

We sent a culture survey87, 88 to THL’s team and found very strong agreement with the statement that their leadership is attentive to the organization’s strategy. In comments, respondents emphasized that their leadership is thoughtful, value-aligned, and skilled at communicating their strategy throughout the organization. They also agreed strongly that their organization promotes both internal and external transparency, with many respondents commenting that THL is the most transparent organization they have ever worked for.

Board of Directors

THL’s Board of Directors consists of six members, including Mark Middleton (chair), who works in the technology industry. Other members include a former THL volunteer, a finance and operations specialist, a corporate consultant, a lawyer, and a cryptocurrency fund manager. In the U.S., it’s considered a best practice for nonprofit boards to be comprised of at least five people who have little overlap with an organization’s staff or other related parties. However, there is only weak evidence that following this best practice is correlated with success. THL is currently recruiting board members and hopes to have seven by the end of 2019.

We think that the relative diversity of THL’s board is a strength. We believe that boards whose members represent occupational and viewpoint diversity are likely most useful to a charity since they can offer a wide range of perspectives and skills. There is some evidence suggesting that nonprofit board diversity is positively associated with better fundraising and social performance,89 better internal and external governance practices,90 as well as with the use of inclusive governance practices that allow the board to incorporate community perspectives into their strategic decision making.91

Strategic Vision and Planning

Strategic vision

THL’s mission is to “end the abuse of animals raised for food.” Given their mission and their history of conducting evidence-supported interventions, we expect THL to remain committed to effectively helping animals.

Strategic planning process

In previous years, THL’s strategic planning process was fairly informal. Their leadership team met in person every few months to discuss their progress and their plans for the next few months.92 In 2018, however, THL began taking a more formal approach to strategic planning.

THL now creates both three-year and one-year formal plans. They are still developing their strategic planning process in consultation with other charities and with strategic planning experts. For the past two years, they underwent a full strategic planning process at the start of the year to define annual priorities and goals. They had both a three-year and one-year plan. Moving forward, however, they plan to revise their organization-wide priorities just every three years through a three-year plan only. They will continue to set their annual goals every year at a retreat, including all department heads and international leadership.93 THL’s leadership seeks input from the entire staff in the strategic planning process, and they encourage discussion. Decisions among leadership are generally made by consensus, but occasionally by deference to the person with the highest level of expertise in the subject.94

Goal setting and monitoring

THL sets detailed goals in line with their annual plans and identifies metrics for monitoring success. They evaluate them quarterly, in addition to during strategic planning sessions.95

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Overall Assessment:

The most effective charities have healthy cultures and sustainable structures to enable their core work. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about the culture they try to foster and their perceptions of staff morale. We review each charity’s policies related to human resources and check for essential items. We also send each charity a culture survey and request that they distribute it among their team on our behalf.

Human Resources Policies

Here we present a list of policies that we find to be beneficial for fostering healthy cultures. A green mark indicates that THL has such a policy and a red mark indicates that they do not. A yellow mark indicates that the organization has a partial policy, an informal or unwritten policy, or a policy that is not fully or consistently implemented. We do not expect a given charity to have all of the following policies, but we believe that, generally, having more of them is better than having fewer.

| A workplace code of ethics that is clearly written and consistently applied throughout the organization | |

| Paid time off THL offers unlimited annual paid time off, which employees may use up to two weeks at a time. Employees must take a minimum of five consecutive days of paid time off per year. |

|

| Sick days and personal leave THL allows employees to use unlimited paid time off to cover sick days and personal leave. |

|

| Full healthcare coverage THL offers full coverage of employees’ healthcare premiums at a gold level plan and life insurance premiums. They also offer a 50% cost share of employees’ vision and dental premiums. |

|

| Regular performance evaluations | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| A formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries |

| A written statement that they do not discriminate on the basis of race, sexual orientation, disability status, or other characteristics | |

| A written statement supporting gender equity and/or discouraging sexual harassment | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| An optional anonymous reporting system | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment or discrimination through all levels of the managerial chain up to and including the Board of Directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| A practice in place of documenting all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular, mandatory trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) | |

| Paid family and medical leave | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for submitting reasonable accommodation requests | |

| Remote work option |

| Audited financial documents (including the most recently filed IRS form 990, for U.S. organizations) made available on the charity’s website | |

| Board meeting notes made publicly available | |

| Board members’ identities made publicly available | |

| Key staff members’ identities made publicly available |

| Formal orientation provided to all new employees | |

| Funding for training and development consistently available to each employee | |

| Funding provided for books or other educational materials related to each employee’s work | |

| Paid trainings available on topics such as: diversity, equal employment opportunity, leadership, and conflict resolution | |

| Paid trainings in intercultural competence (for multinational organizations only) | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure for employees to request further training or support |

In addition to the policies marked in green above, The Humane League has the following policies which seem beneficial, though we have not researched them extensively:

| Mandatory PTO minimum | |

| Private accommodations when traveling | |

| “Twelve weeks of paid parental leave for any parent following the birth, adoption or foster placement of a child” Marked yellow here as this applies for the U.S. only. In the countries where THL has independent entities, local law prevails.) |

|

| Pre-leave checklist for staff taking PTO to support “unplugged” vacations | |

| Reimbursements are provided for full-time staff: home wifi and “bring your own device”96 |

Culture and Morale

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly toward all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. According to THL’s leadership, culture is a priority for their organization. Coman-Hidy describes the culture as “positive and strong.” Gunn told us that their team gets along well and has not had any major problems.

The staff survey we distributed to THL’s team supports leadership’s claim that THL’s culture is highly positive. THL has quite a high level of employee engagement. A few common adjectives that respondents used to describe THL’s culture were “open,” “efficient,” “direct,” “inclusive” and “positive.” Respondents agreed strongly that they get along well with their colleagues, with many commenting that some of their best friends are from THL’s staff.

Overall, roughly 15% of respondents to our culture survey noted in an open-response box that THL has the healthiest culture of anywhere they’ve worked.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion97

One important part of acting responsibly toward stakeholders is providing a diverse,98 equitable, and inclusive work environment. Charities with a healthy attitude toward diversity, equity, and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, which improves their ability to respond to new situations and challenges.99 Among other things, inclusive work environments should also provide necessary resources for employees with disabilities, require regular trainings on topics such as diversity, and protect all employees from harassment and discrimination.

THL is working to create a diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplace, and its staff and leadership seem to be aligned on that goal. THL’s leadership and respondents to our survey both acknowledged that THL has a lack of racial diversity on their team. However, THL has an “equity and inclusion” committee and they are planning to work with Encompass to identify other avenues for further diversifying their team.100 Respondents to our survey seemed optimistic that THL is taking appropriate steps to improve. Staff seemed particularly excited about working with Encompass.

Sustainability

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in leadership. The charity should not seem likely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, it should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

THL has strong and effective leadership, a collaborative culture, comprehensive training systems, and a clear strategy. In our view, they have a talented and committed staff with many trained and capable managers. We think they could likely survive a change in leadership, if necessary.

However, THL is fairly heavily reliant on a small number of large funding sources. In particular, they’ve received several large grants from the Open Philanthropy Project (Open Phil). In 2018, THL received a $10 million grant from Open Phil for general support over 3–5 years. We think that THL would be more stable in the long-term if they could further diversify their funding sources.

Questions for Further Consideration

THL has expanded to several countries with cultural and social circumstances different from the U.S. How is THL addressing challenges arising from their international expansion?

THL’s response:

“In the last year, both the UK and the Mexico branches of THL have become independent charities, and the local leaders have significant latitude to create their own policies and make their own program decisions. We have also organized an international leadership team that works together to discuss our long-term strategy and address topics relevant to the global organization. We do not have further plans for expansion (beyond MX, UK and Japan) and instead plan on working via the OWA to support other international organizations.”

There are many more farmed fishes than other species of farmed animals. Has THL considered allocating more of their resources toward farmed fish advocacy?

THL’s response:

“Each year, an estimated 37 billion–120 billion finned fish are slaughtered in the animal agriculture system, compared to roughly 60 billion–80 billion land animals. For this reason, we agree that helping fish is a valuable area that could use much more work.

We have considered this issue and hope to begin working on fish welfare issues in the future, after winning the broiler reform campaign and doing some work to ensure that cage-free commitments are honored. Seeing these campaigns through to completion is our current priority, and we worry that having a third parallel ask of companies would make all of our projects more difficult to complete.

There are also a number of factors making advocacy on behalf of fish difficult, including limited information about what causes the greatest suffering, the many species of farmed fish, and the potentially lower resonance of the issue with the public.

However, we do see fish slaughter reform as a potential target for corporate outreach to improve fish welfare. Mandating less cruel methods of slaughter has been tractable for other species in the past, and should be possible to apply across the fish farming industry. We are considering this as a potential next step for our corporate outreach.”

Does THL worry that focusing on some of the most extreme confinement practices could lead to complacency with other forms of suffering that farmed animals endure, or with meat consumption?

THL’s response:

“The Humane League’s argument on behalf of welfare campaigns can be found here.101 We feel strongly that incremental victories on behalf of animals build the strength, status, and momentum of our movement, while also resulting in harm reduction for the animals suffering on factory farms. It is very clear to us that a world free from animal suffering starts with a world with less animal suffering.”

Edit 9/03/2020: Initially, we reported that THL spent slightly less than average on corporate campaigns compared to other charities we reviewed in 2019 (Criterion 4), when in fact they spent more than average compared to other charities.

Note that we are never 100% confident in the effectiveness of a particular charity or intervention, so three gray circles do not necessarily imply that we are as confident as we could possibly be.

For more information on the reliability of self-reported data, see van de Mortel (2008) in the Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. Also see Peacock (2018) on the use of self-reported dietary data.

Most people go vegan or vegetarian over a long period (Jabs, Devine, & Sobal 1998; Beardsworth & Keil, 1992; Pfeiler & Egloff, 2018; Mullee et al, 2017), with an abrupt “conversion experience” (Beardsworth & Keil, 1992) being much less common. The adoption of a politicized dietary identity (such as vegetarianism/veganism) has been found to most commonly occur through a series of encounters (Chuck et al., 2016). Thus, when receiving a leaflet, such experiences may contribute to a gradual shift in perspective. NGOs serve as a primary site of awareness-raising, which is key in achieving widespread societal and political change, particularly in the current climate. Researchers into political change have repeatedly argued that awareness-raising is key if we want to change policy (e.g. Basiley et al., 2014). Awareness of reduction motivations does appear to be increasing (Siegrist, Visschers, & Hartmann, 2015) and awareness may be linked to increased reduction (Lee & Simpson, 2016). Leafleting may play a role in this.

We found that charities interpreted the question of how many assets they had very differently. Some interpreted assets as financial reserves, some as net assets, and some as material assets. We have interpreted assets as financial reserves, which we calculated by taking the assets from the previous year, adding the (estimated) revenue for the current year, and subtracting the (estimated) expenses for the current year. There is a discrepancy between the assets that THL provided for 2018, which was $7.4 million (The Humane League, 2019). In the graph, we present the number provided by THL instead of the one based on our calculation.

We have included all financial information available from 2014 until mid-2019.

We assume that charities receive 40% of their revenue in the last two months of the calendar year. To calculate estimates of total revenue, we multiply the revenue from the first six months by 2.778. We assume that expenses stay constant over the year, so to calculate estimates of total expenses in 2019, we multiply expenses from the first six months by 2.

Coman-Hidy of THL noted the following: “The appearance of variation in funding comes from accrual-based logging of large, multi-year grants and don’t represent what has functionally been increasing funding year after year. That is, an entire multi-year grant is accounted for in the income of, say, 2018, even though it’s paid out over two years.” (personal communication, November 14, 2019)

In combination with our estimates of the priority level and costs of each planned expansion, the estimates are based on charities’ own estimates of planned expansion as expressed in our follow-up questions for them (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019).

See ACE’s 2019 cost-effectiveness estimates spreadsheet.

Potential bottlenecks besides lack of funding include lack of operational capacity to support new staff members and difficulty to find and hire value-aligned individuals with the right skill sets. We base our estimates for capacity for expanding staff based on the current number of staff employed, as reported in The Humane League (2019). THL employs 73 full-time and 2 part-time staff in the U.S. and Japan. They employ 14 full-time staff in the U.K. and 4 in Mexico. In total, they employ 91 full-time employees (The Humane League, 2019). Our subjective assessment is that we are highly confident that THL can hire 62% of the new staff they would like to hire before running into non-funding related bottlenecks. For 38% of the hires, we believe the non-funding related bottlenecks play a more significant role and we are only moderately confident that THL can overcome these bottlenecks within the next year. Therefore, we estimate that 62% of new hires are high priority and 38% are moderate priority.

THL says they estimate wanting to hire for 7 specific positions in the U.S. that we think are high priority (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019). We interpret this as them being able to hire between 6 and 9 new staff members.

Salaries are based on current open positions:

– Regional Organizing Manager—starting salary: $56,000 (The Humane League, 2019)

– Senior Donor Relations Officer—starting salary: $56,000 (LinkedIn, 2019)

– National Director of Organizing—starting salary: $64,000 (LinkedIn, 2019)

Based on this, we estimate salaries in the U.S. at THL are between $44,800 (lowest salary mentioned -20%) and $76,800 (highest salary mentioned +20%).Salaries in Mexico are lower than in the US. Based on rough cost of living estimates, we believe THL Mexico staff earn between $18,000 and $35,000 per year (Carpenter, 2019).

Based on the difference in median salaries in the UK and the US, we believe THL UK staff earn 90% the amount US staff earns

Room for more funding which has the purpose of being granted to other organizations is not included in our general model, and is instead mentioned separately in the Estimated Room for More Funding section. Between January 2018 and June 2019, THL granted $182,494.13 via the OWA (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019). Because they hired more staff and are expanding this program, we think they will be able to effectively distribute grants between $400,000 and $2,000,000.

THL noted that this would cover “[a]ny support that [their] staff in Japan require, including one-off projects or new staff” (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019). We interpret this as funding the equivalent of between 0.1 and 1 full-time staff member in Japan.

THL noted that they “would like to continue to increase our salaries and benefits” (Animal Charity Evaluators, 2019)

This is an estimate to account for additional expenditures beyond what has been specifically outlined in this model. This parameter reflects our uncertainty as to whether the model is comprehensive and constitutes a range from 1%–20% of the charities total projected 2020 expenses, which are equal to $10 million.

Because of the way our model is set up, this includes maintaining the current amount of funding used for grants.

To estimate the revenue not influenced by ACE, we consider the total revenue per year and subtract the amount we estimate is influenced by ACE in the same year. We use these numbers to estimate the average growth not influenced by ACE. To calculate the estimated 2020 revenue, we add the average growth not influenced by ACE to the 2019 revenue not influenced by ACE. In the case of THL, the amount of revenue influenced by ACE was $5.0 million between the beginning of 2016 and mid-2019. For details, see our giving metrics reports from 2016, 2017, and 2018. At the time of writing, our 2019 Giving Metrics Report is not yet published.

The total revenue is based on the first six months of 2019 with an uncertainty of ± 10%.

The calculations on which this estimate is based exclude revenue influenced by ACE, and have an uncertainty of ± 20%. The calculations are made via a linear projection of the total revenue of previous years.

Because of the way our model is set up, the cost for expansion includes maintaining the current amount of funding used for grants.

This includes only the estimated growth in the granting program, as maintaining the current size of the granting program is included in the total room for more funding.

While we are able to corroborate some types of claims (e.g., those about public events that appear in the news), others are harder to corroborate. For instance, it is often difficult for us to verify whether a charity worked behind the scenes to obtain a corporate commitment, or the extent to which that charity was responsible for obtaining the commitment.

Note that we have combined these two programs in our analysis due to substantial overlap in their accomplishments.

Since we did not ask charities to provide details about accomplishments prior to 2018, key results before this year were sourced from publicly available information and may be incomplete.

See Animal Charity Evaluators (2018), Animal Charity Evaluators (2017), and Animal Charity Evaluators (2016). For example, see THL’s blog post (Ross, 2017) on a 2017 commitment from Subway to develop a global chicken welfare policy which was influenced by THL’s campaign, including a petition, a billboard, and organized protests. Another example is Costco’s cage-free commitment in 2015, which was reportedly influenced by THL’s campaign that included a petition, online testimonials by students, letters, and protests (Coman-Hidy, 2015).

See The Humane League (2019), The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018) and The Humane League’s Accomplishments and Budget (2016–2017).

Many of THL’s commitments have been achieved in partnership with OWA members and the European Chicken Commitment coalition (European Chicken Commitment, n.d.). For example, Compass Group (2019) suggests that THL, Compassion in World Farming, and the Humane Society have been involved in Compass Group’s European commitment.

THL estimates that their cage-free victories have affected more than 10 million chickens (The Humane League, n.d.). According to one rough estimate, 9–120 chicken-years may be affected per every dollar spent on cage-free and broiler welfare corporate campaigns (Šimčikas, 2019). Capriati (2018) estimates that THL has achieved an outcome roughly as good as 10 hen-years shift from battery cages to aviaries per dollar received.

See THL’s blog post (Hendrickson, 2018) promoting Prop 12.

THL reports that when Proposition 12 in California is fully implemented, it will affect 40 million animals per year (The Humane League, n.d.).

Since we did not ask charities to provide details about accomplishments prior to 2018, key results before this year were sourced from publicly available information and may be incomplete.

The OWA granted $84,000 to 4 organizations in 2017, and they granted over $820,000 to 24 organizations in 2019 (Open Wing Alliance, n.d.).

THL reports OWA grantees securing 84 corporate policies in 2018 and 81 in 2019 (The Humane League, 2019).

Since we did not ask charities to provide details about accomplishments prior to 2018, key results before this year were sourced from publicly available information and may be incomplete.

THL reports 1,997,233 Veg Starter Guides/Cookbooks distributed online (The Humane League, 2019).

THL reports 41,366,594 visits to web pages with factory farm cruelty footage (The Humane League, 2019).

For THL’s reports of their 2017 online outreach data, see The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017-2018). For 2018–2019 reports, see The Humane League (2019).

Note that some charities’ programs do not fit in well with the rest of the reviewed charities according to our categorization of intervention type.

For a longer discussion of the limitations of modeling cost-effectiveness, see Šimčikas (2019).

To estimate their 2019 expenditures, we doubled the financial data provided from January–June 2019.

This includes all charities reviewed in 2019 that are engaged in a program related to corporate outreach.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work. We think it is unlikely that, in practice, volunteers are working full-time weeks, however we are using this unit in order to maintain a comparison with the amount of staff time used.

We provide these estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. For more information, see this explainer page.

We provide these estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. For more information, see this explainer page.

This only includes charities engaged in securing commitment for the animal type in question.

We provide these estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. For more information, see this explainer page.

These estimates are informed by a variety of sources—charities’ self-reported estimates, information about the size and production output of the companies, data from the Open Philanthropy Project, etc. For more details, see our spreadsheet comparing 2019 reviewed charities engaged in corporate outreach, and the accompanying Guesstimate sheet.

See California Secretary of State (n.d.) for organizations providing financial support.

This includes all charities reviewed in 2019 that are engaged in a program related to capacity building/building alliances.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work. We think it is unlikely that, in practice, volunteers are working full-time weeks, however we are using this unit in order to maintain a comparison with the amount of staff time used.

This includes all charities reviewed in 2019 that are engaged in a program related to individual outreach.

To estimate their expenditures, we took their reported expenditures for this program and added a portion of their general non-program expenditures weighted by the size of this program compared to their other programs. All estimates are rounded to two significant figures.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work.

They provided this number in hours, and we converted it into weeks for readability. We assume that one week consists of 40 hours of work. We think it is unlikely that, in practice, volunteers are working full-time weeks, however we are using this unit in order to maintain a comparison with the amount of staff time used.

THL sent their survey to 73 U.S. team members and 61 responded, for a response rate of 85%.

We recognize at least two major limitations of our culture survey. First, because participation was not mandatory, the results could be skewed by selection bias. Second, because respondents knew that their answers could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer, they may have felt an incentive to emphasize their employers’ strengths and minimize their weaknesses.

This policy reimburses staff for the use of their personal computers (D. Coman-Hidy, personal communication, November 25, 2019).

Our goal in this section is to evaluate whether each charity has a healthy attitude toward diversity, equity, and inclusion. We do not directly evaluate the demographic characteristics of their employees. There are at least two reasons supporting our approach: First, we are not well-positioned to evaluate the demographic characteristics of each charity’s employees. Second, we believe that each charity is fully responsible for their own attitudes toward diversity, equity, and inclusion, but the demographic characteristics of a charity’s staff may be influenced by factors outside of the charity’s control.

We use the term “diversity” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of any of the following characteristics: racial identification, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, ability levels, educational levels, parental status, immigrant status, age, and/or religious, political, or ideological affiliation.

There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that teams composed of individuals with different roles, tasks, or occupations are likely to be more successful than those which are more homogeneous (Horwitz & Horwitz, 2007). Increased diversity by demographic factors—such as race and gender—has more mixed effects in the literature (Jackson, Joshi, & Erhardt, 2003), but gains through having a diverse team seem to be possible for organizations which view diversity as a resource (using different personal backgrounds and experiences to improve decision making) rather than solely a neutral or justice-oriented practice (Ely & Thomas, 2001).

For more on THL’s view on incremental change, see David Coman-Hidy: The Long Road to Animal Rights and Aaron Ross: From Welfare to Rights: How Social Movements Win Progress.