The Good Food Institute

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2018 |

| Current Version | 2022 |

Archived Version: November, 2018

What does The Good Food Institute do?

The Good Food Institute (GFI) is working to transform the animal agriculture industry by promoting the development of competitive alternatives to animal-based meat, dairy, and eggs. GFI seeks out entrepreneurs and scientists to join or form startups in the plant-based and cultured meat1 (i.e., meat grown in a culture without animal slaughter) market sectors. They provide business, legal, scientific, and strategic guidance for plant-based and cellular product companies. They also engage in regulatory and statutory policy work to level the playing field for plant-based and cellular products in the consumer market. GFI builds relationships with food processing companies (e.g., Tyson, ADM), chain restaurants, grocery stores, and foodservice companies to improve and promote cultured and plant-based alternatives to animal products. Finally, GFI works with grant-making institutions, corporations, and governments to mobilize resources for research in plant-based and cultured meat.

What are their strengths?

We believe that developing competitive alternatives to animal products could have an enormous impact for farmed animals in the long term. It could cause consumers to purchase fewer animal products, and it might do so much more quickly than using moral arguments to persuade consumers to stop eating meat, dairy, and eggs. We feel confident in GFI’s leadership and strategic vision. They are focused on effectiveness and seem determined to maximize the efficiency of their operations and the impact of their work. Our impression, from a variety of sources, is that GFI has been involved in one way or another in a large portion of the major developments in the plant-based and cultured meat sectors since their founding.

What are their weaknesses?

GFI was launched in February 2016, so their track record is quite short and does not yet include some of the outcomes they most hope to accomplish, e.g., the successful development of cultured meat, dairy, and eggs. We expect that it will take some time—perhaps decades—to develop cultured meat that can compete commercially with conventional meat. GFI has had more short-term success in helping companies develop and market plant-based alternatives to meat, but it is still unclear what would have happened in these cases had GFI not been involved.

Internally, GFI has been expanding quite quickly; they grew from ten employees at the end of 2016 to 55 as of October 2018. We have some concerns about the workload of some members of their team, since the organization is hiring and building its infrastructure concurrently with doing their normal work. We also have some concern about GFI’s Board of Directors, which may lack sufficient independence from GFI’s team, and which does not have term limits.

Why did The Good Food Institute receive our top recommendation?

Animal advocates have been working for decades to weaken the animal agriculture industry by encouraging individuals and institutions to reduce the demand for animal products and implement humane reforms. We are happy to support the effective implementation of those interventions, but we also believe that engaging in a wider range of promising tactics may increase the animal advocacy movement’s chance of success. Developing and promoting attractive alternatives to animal products seems like a promising way to disrupt the animal agriculture industry. There are few charities working in this area, and GFI has shown strong leadership and efficiency. We are pleased to recommend donating to them.

How much money could they use?

We estimate that GFI has a total funding gap of approximately -$90,000 to $5.2 million, and that they could effectively put to use a total revenue of $9.8 million–$13.4 million.2, 3, 4 We expect they would use additional funding to expand their programs in science and technology, innovation, policy, corporate engagement, and to simultaneously scale their operating reserve and organizational infrastructure (executive, finance, operations, and development) . We also expect them to continue their international expansion.

What do you get for your donation?

Your donation supports GFI’s programs to make progress on the development of plant-based and cultured meat technologies. From an average $1,000 donation, GFI would spend about $180 on operations, $150 on their policy program, $140 on their science and technology program, $140 on international engagement, $120 on development, $110 on their innovation program, $100 on communications, and about $60 on corporate engagement. The impact that donations to GFI have for farmed animals is more speculative and long-term than the impact of donations to one of our other Top Charities. Given the speculative nature of GFI’s impact on farmed animals, we currently have not completed a cost-effectiveness estimate for donations to GFI. Still, we think donations to GFI have quite high expected value.

We don’t know exactly what GFI will do if they raise additional funds beyond what they’ve budgeted for this year, but we think additional marginal funds will be used similarly to existing funds.

The Good Food Institute has been one of our Top Charities since November 2016.

While ACE uses the term “cultured,” we note that GFI prefers the term “clean meat” to “cultured.” They explained why in a blog post from September 6, 2016, and in a subsequent blog post from September 27, 2018.

These estimates are based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for The Good Food Institute.

Although the low end of the funding gap estimate is negative, that does not indicate that we think GFI is likely to be overfunded—we think they most likely still have significant room for more funding.

These ranges are subjective confidence intervals (SCIs). An SCI is a range of values that communicates a subjective estimate of an unknown quantity at a particular confidence level (expressed as a percentage). We generally use 90% SCIs, which we construct such that we believe the unknown quantity is 90% likely to be within the given interval and equally likely to be above or below the given interval.

Table of Contents

- How The Good Food Institute Performs on our Criteria

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Questions for Further Consideration

- Supplemental Materials

How The Good Food Institute Performs on our Criteria

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Before investigating the particular implementation of a charity’s programs, we consider their overall approach to animal advocacy in terms of the cause(s) they advance and the types of outcomes they achieve. In particular, we consider whether they’ve chosen to pursue approaches that seem likely to produce significant positive change for animals—both in the near and long term.

Cause Area

GFI focuses primarily on developing plant-based and cultured alternatives to animal products, which will benefit farmed animals. We believe farmed animal advocacy to be a high-impact cause area.

Types of Outcomes Achieved

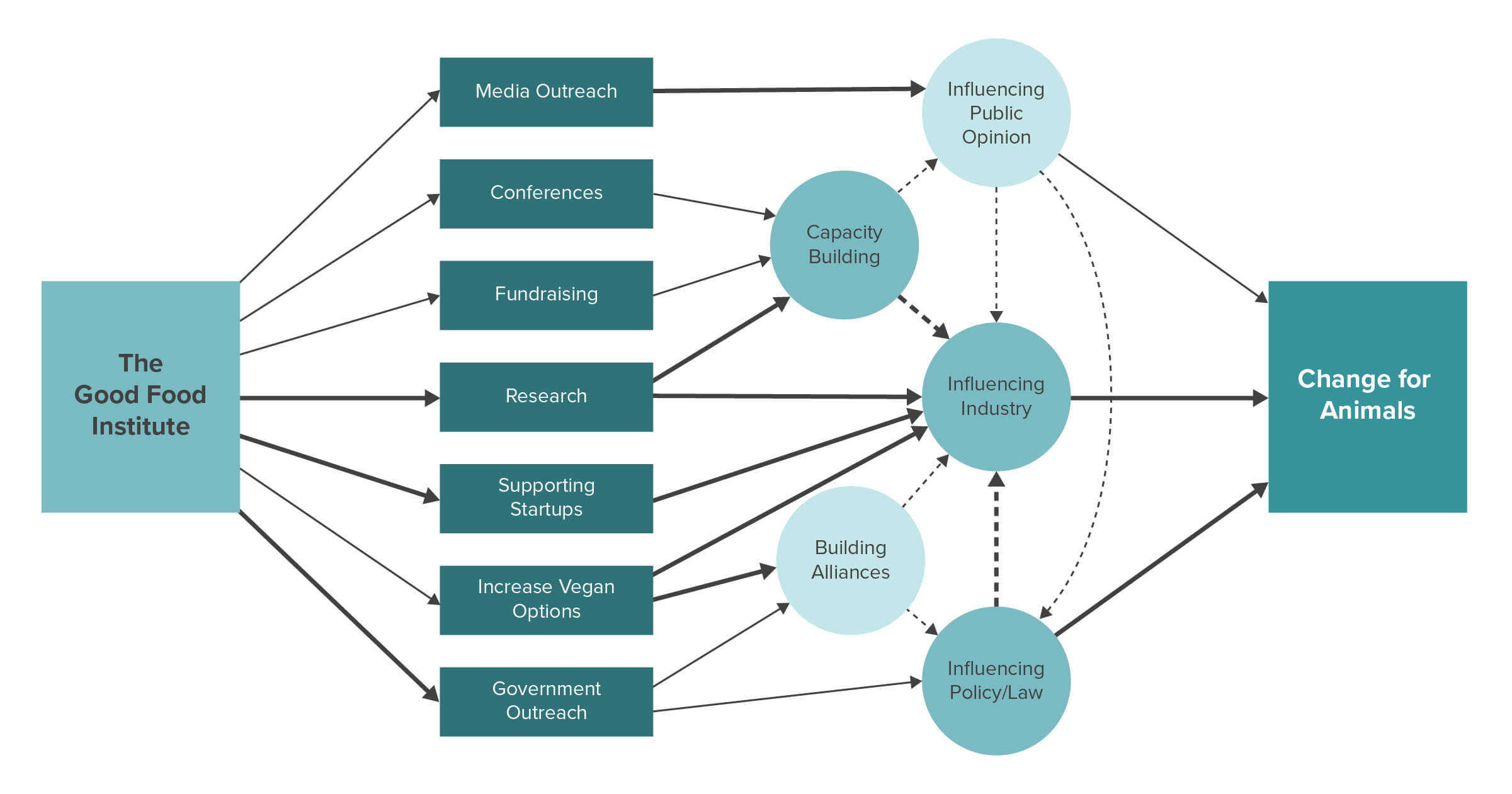

To better understand the potential impact of a charity’s programs, we’ve developed a menu of outcomes that describes five avenues for change: influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

GFI pursues many different avenues for creating change for animals: they work to influence public opinion, build the capacity of the movement, influence industry, build alliances, and influence policy and law. Pursuing multiple avenues for change allows a charity to better learn about which areas are more effective so that they will be in a better position to allocate more resources where they may be most impactful. However, we don’t think that charities that pursue multiple avenues for change are necessarily more impactful than charities that focus on one.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small and/or uncertain effects.

Influencing Public Opinion

Though it is not their primary focus, GFI works to influence individuals to adopt more animal-friendly attitudes and behaviors through media outreach, which we view as an especially promising approach.1 While it is difficult to measure incremental changes in public opinion—and, consequently, difficult to know when an intervention is more or less successful—we still think it’s important for the animal advocacy movement to target some outreach toward individuals. This is because a shift in public attitudes and consumer preferences could help drive industry changes and lead to greater support for more animal-friendly policies. However, we find that efforts to influence public opinion seem much less neglected than other categories of interventions in the United States.2

While GFI isn’t primarily focused on affecting public opinion, they likely have some impact through their media outreach. GFI has been proactive about building relationships with the media by providing information about cultured and plant-based meat as well as writing op-eds and participating in news features.3 This work has not been limited to scientific or technical outlets but rather has been aimed at the mainstream audience in an effort to get plant-based and cultured meat discussions into the public.4 While the impact of this work on consumer attitudes remains to be seen, it does seem that increasing the awareness of the existence and benefits of cultured and plant-based meat is a logical first step towards shifting consumer preferences.

Capacity Building

We see GFI’s outreach on college campuses, hosting of conferences, and directing of funds from other causes to animals as especially effective forms of capacity building.5 Working to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement can have far-reaching impact. While capacity-building projects may not always help animals directly, they can help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Our recent research on the way that resources are allocated between different animal advocacy interventions suggests that capacity building is currently relatively neglected compared to other outcomes, such as influencing public opinion and industry.

GFI has helped contribute to the development of foundational knowledge necessary for the growth of plant-based and cultured meat production. They have done this directly by publishing scientific white papers6 and consumer research, and by hosting and presenting their findings at conferences. They have also contributed indirectly by working to catalyze progress in the field more generally. For instance, GFI incentivizes scientific developments in cultured meat with cash prizes (underwritten by industry sponsors) for Researchers working on these issues. They also find funding and work to identify and connect the Researchers who are best positioned to make an impact with the funding they need to do so. As part of their work to recruit students, scientists, and entrepreneurs to work in cellular agriculture and plant-based technology, GFI contributed to the development of the first university course in plant-based meat7 and the Alternative Meats Lab, both at UC Berkeley. Through collaboration with the Cellular Agriculture Society (CAS), they also helped to develop a course on plant-based and cultured meat at Stanford, which one of GFI’s scientists is teaching.8 They are also working to create two university-based research centers—one for cultured meat research and one for plant-based product research.9 The course at UC Berkeley is a competition-based lab within an entrepreneurial program, while the course at Stanford is a more traditional format within their science department. While we think the development of such courses and research centers is promising since they plausibly provide additional entry points for people to get involved in the field, we’re generally unsure about the marginal impact of efforts to recruit students and scientists to work in food technology.

We also consider some of GFI’s fundraising activities to be capacity building, in part because they build connections across movements. Whereas many animal charities draw funds primarily from within the movement (e.g., from donors who might have otherwise given to other animal charities), GFI is also seeking to reach potential donors whose primary interests are in environmental protection, the sustainability of the global food system, and human health.10 GFI also works to convince academic institutions, government agencies,11 and other major funders12 to invest in alternatives to animal products. In contrast to securing funding from donors who might have donated to another organization in the area of animal advocacy, some of these funds would probably not have otherwise been used to help animals. In this way, GFI’s fundraising activities might be more effective than other animal charities’ fundraising activities at building the capacity of the movement.

Influencing Industry

We think that developing plant-based and cultured products is a potentially high-impact way to influence the food system.13 Successfully increasing the quality and availability of cultured and plant-based foods may help to create a climate in which it’s easier for individuals to reduce their use of animal products. Plant-based milk, for example, is already showing a tendency to displace the sales of conventional milk in the U.S.14 In the long term, this reduced demand for animal-based products could weaken the animal agriculture industry—potentially lessening its lobbying power and enabling stricter regulation of animal welfare standards. GFI has stated that if plant-based meat captured the same share of the meat market that plant-based milk has captured of the milk market, it would spare over 1 billion land animals (and even more sea animals) annually in the United States alone.15

GFI provides strategic and technical support to over 100 plant-based and cultured meat entrepreneurs.16 They provide fundraising strategy, facilitate connections and identify funding opportunities for startups, and bring plant-based and cultured meat science to professional and academic conferences. GFI also conducts literature reviews and writes white papers to consolidate and disseminate knowledge throughout the field. They aim to effectively funnel funding to where it will be most impactful by (i) conducting research to identify areas ready for investment and success and (ii) by meeting with venture capital groups and large meat companies to direct funding to these opportunities in cultured and plant-based meat.

Another avenue for impact is through GFI’s work in corporate outreach within the animal agriculture industry17 and the consumer market. They aim to alter the consumer landscape by working with large restaurant chains to increase plant-based offerings. One piece of this work has been the creation of a scorecard of the largest 100 restaurant chains that ranks them according to their availability of plant-based options. They are also working with grocery stores to increase the availability of plant-based options and to improve the marketing for them. They plan to create a scorecard for grocery stores, similar to their restaurant scorecard.18 This may have a more immediate impact on animals than their work to support the development of cultured products which have yet to come to market.

GFI is conducting international outreach with governments (Singapore, Brazil, India, Israel, Czech Republic, UAE, and France) and entrepreneurs (India, Israel, Mexico, Brazil, China) so that the displacement of animal agriculture by plant-based and cultured products can be a global process. This year, GFI supported the launch of Dao Foods International, a company working to bring plant-based eating and cultured meat research to China.19 While the success of this venture remains to be seen, it is potentially very high impact due to China’s large population and rapidly increasing consumption of meat.20

Building Alliances

GFI’s outreach to key influencers and work with major food corporations and restaurants provides an avenue for high-impact work, since it can involve convincing a few powerful people to make decisions that may influence the lives of millions of animals.21 Unless these key influencers are significantly more difficult to reach, this seems more efficient than general individual outreach because a great deal more individuals would need to be reached to create an equivalent amount of change.

GFI works with many key influencers. For instance, GFI’s science team has met with and presented to many of the largest U.S.-based venture capital groups, as well as many key innovation-focused investors.22 GFI’s corporate engagement team engages with many of the world’s largest meat companies.23

GFI encourages and facilitates collaboration within the plant-based and cultured meat industry by bringing together cultured meat companies from around the world quarterly, and by hosting a monthly call with approximately 60 entrepreneurs and a Slack group with over 350 entrepreneurs.24 GFI has a recently hired a business analyst working to increase participation within the Slack group, which is currently not used consistently.25 Increasing the cooperation among the various players in the plant-based and cultured meat sector could potentially accelerate growth. This may eventually help to level the playing field with the much larger and more developed animal agriculture industry. GFI’s strategy involves trying to convince the largest meat producing companies in the world to view the growing demand for plant-based and cultured foods as an opportunity for transformation rather than as a disruption they would have to fight.26 Beyond directly working with corporations, GFI also lobbies congress,27 the USDA,28 and FDA29 for decisions that could have far-reaching impact—these groups can make changes on a national scale. Taken all together, GFI’s work to build alliances with large food companies and key influencers has the potential for large-scale and far-reaching impact.

Influencing Policy and the Law

GFI conducts legal research and lobbying with the goal of bringing plant-based and cultured meat to market. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects to be particularly long-lasting.

GFI works to influence government policies and laws by engaging in outreach to congressional staff, writing op-eds and white papers,30 testifying about the environmental impact of animal agriculture, researching potential regulatory pathways for cultured products,31 and lobbying for plant-based and clean meat. GFI also organized an event promote plant-based meat; the event was held on Capitol Hill and was co-sponsored by Beyond Meat. Some of this work aims to shift spending from research on animal agriculture to research on plant-based proteins,32 while other efforts aim at combating unfair use of funds, opposing subsidies for animal agriculture, and promoting the use of plant-based foods in school lunches.33 The immediate impact on animals of much of this work is limited. However, advances in plant-based and cultured product development may be able to have a larger impact, to the extent that they are successful. The ultimate impact of much of this work is contingent on GFI and their allies successfully outmaneuvering the much larger meat and dairy industries, and on the progress of the plant-based and cultured meat industry more generally.

GFI is also working to clear regulatory hurdles and to ensure a clear path to market for cultured meat. Since there are not many groups working towards favorable policies supporting plant-based and cultured foods, we are uncertain about the tractability of this work. However, given that GFI is one of only two groups we are currently aware of working in this neglected area in the U.S.,34 there is potential for this to be a high-impact strategy.

Long-Term Impact

Though there is significant uncertainty regarding the impact of interventions in the long term, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.35 The potential number of individuals affected by a charity increases over time due to both human and animal population growth, as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Predictions about the long-term impact of any intervention are always extremely uncertain, because the effects of an intervention vary with context and are interdependent with concurrent interventions—with neither of these interactions being constant over time.36 When estimating the long-term impact of a charity’s actions, we consider the context in which they occur and how they fit into the overall movement. Barring any strong evidence to the contrary, we think the long-term impact of most animal advocacy interventions will be net positive. Still, the comparative effects of one intervention versus another are not well understood.37 Because of the difficulties in forecasting long-term impact, we do not put significant weight on our predictions.

Most of GFI’s strategy is directed towards long-term goals. Their work to build the capacity behind the development of alternatives to animal-based foods, their lobbying for change within the government to make the success of these ventures more likely, and their efforts to transform the food industry all have a focus on the future. Because so much of their work focuses on large-scale change and there are many obstacles to overcome, the potential for impact is mostly long term.

The long-term impact of GFI’s work on cultured products is potentially very positive and, at the same time, highly uncertain. The impact could be hugely transformative if the industry is successful in developing cultured products that would plausibly alter the consumer landscape from one where we need to ask for a significant behavior change—from eating meat to not eating meat—to one where we only need to ask for a relatively small behavior change—from eating one kind of meat to eating another. However, the ultimate success of this outcome relies on (i) consumer acceptance of cultured products and (ii) the ability of the cellular agriculture industry to reach cost competitiveness with the animal agriculture industry. Some evidence suggests that consumer acceptance of cultured meat may have improved in recent years but still remains low.38 The technology is advancing, and GFI was recently awarded funding39 by Y Combinator, an accelerator with a top reputation for identifying promising startups.40 All this speaks to the promise of this venture, though it remains unclear how long it will take for cultured meat to become cost-competitive, or if it ever will.41

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

In order to recommend a charity, we need to assess the extent to which they will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. Specifically, we need to consider whether there may be non-monetary “bottlenecks,” or barriers to the charity’s growth. First, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. Next, we evaluate the charity’s room for more funding by considering existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential new programs and areas for growth. It is important to determine whether any barriers limiting progress in these areas are solely monetary, or whether there are other inhibiting factors—such as time or talent shortages. Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for more funding sooner than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we have suggested. Our estimates are intended to indicate the point at which we would want to check in with a charity to ensure that they have used the funds they have received effectively and are still able to absorb additional funding.

Recent Financial History

While much of GFI’s work aims to support the development of products for the consumer market, they rely completely on grants and philanthropy for their funding.42 They have met significantly larger fundraising goals every year and are continuing to work towards meeting a larger fundraising goal of $7.5 million in 2018 following the expansion of their development team.43

The chart below shows GFI’s recent revenues, assets, and expenditures.44

Planned Future Expenses

At the moment, GFI is continuing their rapid growth. When we reviewed them in 2017, they were aiming to staff up to 38 employees by the end of the year, nearly quadrupling their size at the start of the year.45 As of October 2018, they have 55 people on staff and are planning to expand internationally. If they meet their fundraising goal of $7.5 million, they plan to expand to a total of around 70 U.S. team members and roughly 20 overseas staff in 2019.46

Out of eight main areas in which they plan to allocate funding in 2018, they report that the largest allocations will go towards (i) their operating reserve (17% of their total budget), and (ii) executive finance and operations (13% of their total budget).47 Following those areas, communications, international engagement, and science and technology will each receive about 12% of their total funding.48 The policy department will recieve about 10%, while innovation, corporate engagement, and development will each receive about 8% of total funding.49

GFI operates on a rolling budget, so their spending next year will be based on the amount of money they raise this year.50 Though their goal of expanding their international staff may come with new hiring challenges due to distance and cultural differences, they may benefit from already having staff on the ground in Brazil, Israel, India, and China. GFI has budgeted around $1 million for their 2019 international expansion and they have expressed a desire to expedite international expansion if they exceed their current funding goals.51

Last year we anticipated that GFI would slow their expansion after such rapid growth.52 While their planned growth for 2019 is less than it was for 2018, they have continued to expand significantly and have been taking steps to expand their fundraising infrastructure so they can sustain this growth.53 While they acknowledge limits to how quickly they can scale up their own programs, they have expressed confidence that they can put additional funds to good use in funding research proposals and supporting the growth of the industry.54

Assessing Funding Priority of Future Expenses

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area will likely vary in its potential cost effectiveness. In addition to evaluating a charity’s planned future expenses, we consider the potential impact and relative cost effectiveness of filling different funding gaps. This helps us evaluate whether the marginal cost effectiveness of donating to a charity would differ from the charity’s average cost effectiveness from the past year. We break down the total room for more funding into three priority levels, as follows:

High Priority Funding Gaps

Our highest priority is funding activities or programs we think are likely to create longer-term impact in a cost-effective way, as well as programs which we have relatively strong reasons to believe will have a highly positive short- or medium-term direct impact in a cost-effective way.55

As described in Criterion 1, GFI has a number of programs that we consider promising, including: conducting media outreach, working with corporations to increase plant-based offerings and develop cultured products, conducting and supporting research, engaging in international work, and attempting to influence policy and the law. Of these programs, we estimate they could effectively use the largest increases in funding to support international expansion56 and research of plant-based and cultured products.57 In terms of staffing, we also think they have significant room for funding to move towards their planned expansion from 49 staff to 70 staff in 2019.58 We estimate that GFI has a high priority funding gap of $1.7–$4.1 million for 2019.59, 60, 61

Moderate Priority Funding Gaps

It is of moderate priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively moderate marginal cost effectiveness.

Due do the high cost, it’s uncertain how soon GFI’s goal of opening research centers at universities will be feasible.62 Considering their other work to increase the numbers of students and scientists in the cultured and plant-based meat field—such as supporting the development of university courses and the offering cash prizes—we estimate that GFI has a moderate priority funding gap of $250,000–$1.6 million for 2019.63

Low Priority Funding Gaps

It is of low priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively lower marginal cost effectiveness, or to replenish cash reserves. Because it is likely that there may be future expenditures we haven’t thought of, we also include in this category an estimate of possible additional expenditures (based on a percentage of the charity’s current yearly budget).

Using a range estimate of 1%–20% of their projected 2018 expenses to account for possible additional expenditures, we estimate that GFI has a low priority funding gap of $60,000–$1.7 million for 2019.64

The chart below shows the distribution of GFI’s gaps in funding among the three priorities:65

GFI has a fundraising goal of $9 million in 2019, which is $1.5 million more than their goal in 2018 and approximately $4 million more than they raised in 2017.66 We estimate that next year they have a total funding gap of approximately -$90,000 to $5.2 million,67, 68 and that they could effectively put to use a total revenue of $9.8 million–$13.4 million.69 They have estimated that they could effectively use an additional $5–$10 million beyond their $9 million goal to scale up their current work even more significantly and to expand their international efforts.70 Further, they estimate that they could effectively direct up to $90 million to support research through the establishment of a research center at a university and by giving out grants to support research.71 Our estimate is only about what they could put to use in the next year, whereas the establishment of a research center seems like a more long-term goal.

Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

We think quantitative cost-effectiveness estimates are often useful factors in charity evaluations, but we are concerned that assigning specific figures can be misleading and can make these estimates appear to carry more weight in our evaluation than we intend. For GFI in particular, we believe that our best estimate of their cost effectiveness is too speculative to feature in our review or include as a significant factor in our evaluation of their effectiveness.

Additionally, GFI is focused on helping animals in the medium and long term, and we have not published estimates of the medium-term or long-term impacts of any other charities—so we worry that including this in a cost-effectiveness calculation would be unfair to those other organizations.72 Our lack of a cost-effectiveness estimate for GFI does not necessarily indicate that they have lower overall cost effectiveness than the charities for which we have completed a cost-effectiveness estimate.

In the future, we hope to have better ways of evaluating medium- and long-term impacts, which could lead to publishing a cost-effectiveness estimate for GFI. We think cost-effectiveness calculations will still be most useful as one small component in our overall understanding of charity effectiveness.

Budget Changes Since 2016

The chart below shows the ways in which GFI’s budget size and allocation has changed since 2016. The data for each year runs from July to June.

Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

To evaluate a charity’s track record, we consider how well the charity has executed previous programs. We also consider the extent to which these previous programs caused positive changes for animals. Information about a charity’s track record helps us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments—information that cannot always be incorporated into the criteria above. An organization’s track record can be a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences in other important factors.

Have programs been well executed?

Founded in October 2015 and officially launched in February 2016, GFI is a relatively young organization. Their international engagement programs, communications department, policy department, and corporate engagement department were all established in 2017, making their track records limited. That said, it’s our view that their programs are generally well executed and have lead (or will likely lead) to positive change.

GFI’s science and technology department is involved in the development and promotion of cellular agriculture research (the science of plant-based and cultured meat, dairy, and egg technologies).73 It’s our view that the department’s core foundational work74 has been well executed. For example, they’re currently completing a 30-page production volume and cost-analysis white paper which will inform targets for cultured meat price points to achieve economic viability.75 Their work to mobilize funding for academic research and commercialization of plant-based and cultured meat has the potential to be particularly impactful, especially as they’ve told us that their policy is to publish all of their research so that the industry as a whole can benefit.76) GFI believes that the presentations that Senior Scientist Dr. Liz Specht gave to various venture capitalist firms in the last two years played a key role in the firms investing more than $15 million into cultured meat.77 It is unclear how the firms would have invested had Dr. Specht not given the presentations, but we are optimistic that they may have played a significant role in these decisions. Finally, the science and technology department successfully developed plant-based meat courses at UC Berkeley. The courses were popular enough that UC Berkeley decided to introduce a permanent “Program for Meat Alternatives” course, which GFI co-designed and plans to replicate nationally.78

GFI’s international engagement department has focused on mapping the landscape of meat production and consumption in numerous countries. This work aims to determine how to effectively make progress on research and development, as well as product development, in the plant-based meat space in each country.79 In addition, GFI reports meeting with government agencies and meat and egg companies in various countries, as well as contacting entrepreneurs in various countries.80 Perhaps GFI’s greatest accomplishment under the umbrella of international engagement is their contribution to the launch of DAO Foods International,81 a Chinese company that aims to bring plant-based eating and cultured meat research to China.82 While the success of this venture remains to be seen, it is potentially very high impact due to China’s large population and increasing consumption of animal products.83

GFI’s innovation department has two primary areas of focus—firstly, encouraging experts and entrepreneurs who may have had limited interest in this topic to join the plant-based and cultured meat industries, and secondly, supporting the ongoing success of existing companies in the industry.84 GFI reports supporting more than 100 plant-based and cultured meat startups by providing assistance with the likes of fundraising strategy and lending communications expertise. For example, they conducted a pilot survey for naming a cultured meat company and helped companies design their packaging for maximum consumer acceptance.85 They have assembled a list of potential companies based on what they believe are promising ideas that have not been capitalized on.86 They have also developed a list of more than 350 entrepreneurs and experts, many of whom take part in monthly video calls led by GFI.87 Over the past two years, they have had some success in assisting in the founding of a plant-based meat company in India, Good Dot, and a plant-based fish company in the U.S., SeaCo (aka Good Catch).88 They’ve also assisting in founding Terramino Foods89 and DAO Foods International.90 Some of these companies have reportedly raised millions of dollars in venture capital and are making progress towards competition with animal products.91, 92 Although venture capitalist funding is an indication that the companies themselves will be successful—and the companies might not exist without GFI—it is unclear what portion of the responsibility for the companies’ outcomes should be attributed to GFI.

One of GFI’s policy department’s main reported accomplishments was their involvement in co-hosting an inaugural reception on Capitol Hill.93 In addition, they successfully lobbied to include language supporting research into plant proteins in a report accompanying the Senate Agriculture Appropriations Bill.94 They also filed an official petition to protect plant-based food companies from labeling regulations that would put them at a disadvantage against animal agriculture industries.95

GFI’s corporate engagement department’s achievements include: (i) advising some of the largest meat companies in the world on opportunities in plant-based and cultured meat, (ii) establishing relationships with top plant-based meat, dairy, and egg companies, and (iii) establishing a ranking of the top 100 U.S. restaurants’ menus for availability of plant-based options.96 GFI also had their inaugural conference this year, The Good Food Conference which aims to accelerate the commercialization of plant-based and cultured meat.

Have programs led to change for animals?

GFI’s theory of change is based on achieving medium- and long-term change for animals, so many of their accomplishments have not yet led to change for animals. Their capacity building in the plant-based and clean meat movement, their lobbying for change within the government, and their efforts to transform the food industry are all intended to help animals in the medium- to long-term future. Because so much of their work focuses on large-scale change and there are many obstacles to overcome, the impact of their programs on animals may often not be immediate. Since they work to foster the field of cultured animal product development—rather than developing individual products themselves—any impact they have will happen through others whose work they support.

GFI’s main reported communications accomplishments in the past year are their various publications in a range of mainstream media (TV, radio, online, print, TEDx talks, etc.) that may have reached tens of millions of people.97 It is possible that the media attention that GFI has earned might have had some direct and indirect benefits for animals. For instance, there is weak evidence that media coverage of the treatment of farmed animals is related to decreased meat consumption in the United States.98 GFI has raised concerns in widely-read publications99 about the impacts of industrialized animal agriculture, including its contributions to climate change and its unsustainability. Some animal advocates are concerned, however, that the messaging of cultured meat companies could reinforce the notion that we need to eat animal flesh, and this could inhibit the spread of vegetarianism and veganism—especially if cultured meat technologies fail to become cost-competitive.100

Last year, GFI reported that the two companies that have launched under GFI’s influence101 in 2016 and 2017 (Good Dot and SeaCo) were expected to produce commercial plant-based products that would compete with existing animal products by early 2018.102 Good Dot reached these expectations and reportedly sold several hundred thousand products over the course of 2017103—they now have products available across thousands of stores in India.104 SeaCo (aka Good Catch),105 Terramino Foods, and DAO Foods International haven’t yet brought any products to market, so we are uncertain as to how well they will perform—and thus how much change they will create for animals. If they succeed at reducing demand for animal products, this could affect a large number of animals. Since GFI works to foster the field of plant-based and cultured animal product development rather than developing individual products themselves, any impact they have will happen through the work of others who they have helped support. The assistance that GFI has provided to these companies has helped them to launch into the plant-based foods market. However, these companies must continue to grow and experience success after receiving outside funding before their products can come to market and potentially reduce the demand for the products of animal agriculture.

If cultured meat becomes cost-competitive with conventional meat, the impact for animals could be enormous. GFI estimates that cultured meat could become cost-competitive with conventional meat in about a decade.106 The Open Philanthropy Project (Open Phil) reports that one of two tissue engineering scientists they spoke with gave a similar estimate—though Open Phil themselves remain much more pessimistic about the timeline for the widespread commercial availability of cultured meat.107 We are not certain whether it is realistic to expect cultured meat to become cost-competitive with conventional meat within a decade; we perceive that timeline to be optimistic.108 The timeline is particularly uncertain and could easily be delayed at these initial stages of development as the earliest scientific and regulatory hurdles are tackled. We expect research and funding into this area to grow as the barriers to eventual success diminish. If GFI and other similar organizations were not doing their current work to overcome the scientific and regulatory hurdles, we expect that commercialization might take somewhat longer.

Cost-competitive cultured meat could impact animals by reducing the demand for animal products. Plant-based dairy products such as milk continue to take market share from the sales of dairy milk in the U.S., with sales in the former category growing as sales in the latter category decline.109 It seems likely that cultured meat products will have similar effects—sometimes replacing plant-based products, but also replacing products of animal agriculture—particularly because they will likely be harder to distinguish by taste and texture than current substitutes.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

A charity that has systems in place for assessing their programs is better equipped to move towards their goals effectively. By conducting self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs, and modify or end those that are less successful. When such systems of improvement work well, many stakeholders benefit: benefactors are inclined to be more trusting and more generous, leadership is able to refine their strategy for achieving their goals, and nonhuman animals benefit more.

To evaluate how well the charity adapts to successes and failures, we consider: (i) how the charity has assessed their past programs and (ii) the extent to which the charity updates their programs in light of those assessments.

Does the charity actively assess areas of success and failure?

GFI has achieved quite a few accomplishments in their first three years, but their track record is understandably shorter than the track records of some more established groups. In 2016, their innovation department and their science & technology departments were their two core departments, and represented the largest focus of their work. In 2017, there was a shift in GFI’s allocation across department areas.110 In 2018, GFI’s main focus areas are on their departments for science and technology, innovation, policy, corporate engagement, and international engagement.111 Currently, GFI assesses their work mainly based on staff members’ progress on their individual quarterly goals.112 In addition to being time-bound, these goals are often specific and measurable, allowing GFI staff to recognize success or failure.113, 114 All of these individual goals are fairly well-aligned with the longer-term goals of their respective departments and the organization’s overall strategic plan, making them remarkably relevant to GFI’s overall mission; they also appear to be challenging and yet pragmatic and plausibly achievable. These goals thus appear to be fairly well-designed for guiding GFI’s actions and assessing their progress towards GFI’s broader mission.

In ACE’s 2017 Review of The Good Food Institute, we analyzed GFI’s goal-setting document containing all their staff’s quarterly goals and progress on the outcomes related to these goals and we are satisfied with their consistent tracking of goals and outcomes. While they have put a lot of work into goal setting and accountability, they reported that there is still room for improvement in that respect.115 Since GFI’s number of staff has grown from seven employees in 2016 to 55 employees in 2018,116—and since they are committed to providing staff with a high level of autonomy—more centralization and operational support could have allowed them to be more successful in their work.117 According to GFI’s Executive Director, some staff goals were more clearly aligned to measurable key performance indicators (KPIs) and to the organization’s mission than others.118 This indicates that GFI has some awareness of how differentially measurable their relevant goals appear to be.

Importantly, it is difficult for GFI to quantitatively estimate most of their programs’ cost effectiveness at this point in their development, since their programs are designed to produce long-term outcomes and they are still a fairly young organization. Still, GFI has told us that they are carefully tracking all of their outcomes, including the amount of money being invested in the cultured and plant-based meat industries as a result of their work.119 They have also expressed an interest in evaluating the number of animals helped by their programs.120 We believe that making these kinds of rough estimates can be a useful way for organizations to self-evaluate.

Does the charity respond appropriately to areas of success and failure?

GFI has shown that they are eager to improve their work both on the programmatic level and the organizational level. With regard to the former, they reported making strategic improvements across all of their programs, though the improvements they listed as most notable were in the departments of policy, corporate engagement, science & technology, and innovation.121 Part of their innovation department’s work includes maintaining a list of “white space” companies that represent promising plant-based and clean meat opportunities. When GFI initially published this list, they waited for entrepreneurs to approach them, and promoted these promising opportunities through channels such as their GFIdeas entrepreneur community. To increase the chances of bringing strong teams together, GFI has shifted their strategy and now actively recruits founders for new companies. For example, they now actively connect with people with the relevant expertise to encourage them to apply their skills to plant-based and clean meat technologies.122 This shift in approach suggests that GFI actively tries to increase their programs’ successes.

GFI has also shown that they are continuously trying to improve their organizational effectiveness. For instance, to increase centralization as their organization grows, and to deliver on their 2017 promise of better evaluating themselves using KPIs, GFI hired a strategic implementation specialist to join their team in August 2018.123 The goal of this new hire is to ensure that the KPIs are synchronized across all departments and staff members, while also ensuring that those KPIs are aligned with GFI’s strategic plan, mission, and vision. We believe that using KPIs effectively would help them to track their goals more concretely and potentially allow for better measuring of progress than their current system. They currently self-evaluate largely based on individual-level quarterly goals, which appear to be generally well designed for indicating success and failure, making it likely that this will be the case for their updated process as well.

In addition to working on their goal-setting process, GFI demonstrated some willingness to improve their hiring processes in response to difficulties finding talent, and in response to staff feedback. Though progress had already been made at the time of our last review (in 2017),124 they have improved on their hiring process further still since then. GFI now has three staff members who are dedicated to recruitment.125 This development has led to methodical recruitment processes that have reportedly been working extremely well126 and have helped GFI significantly grow in staff size. GFI tells us that their growth has eased the workload of some staff who may have been at risk of burnout.127 The staff’s workload is expected to be further eased this year through the hiring of executive assistants for each department. GFI tells us that they hope this will also help free up some of their staff to focus on their specialties rather than spend a lot of time on recruitment or doing other administrative tasks.128

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

A charity is most likely to be effective if it has a well-developed strategic vision and strong leadership who can implement that vision. Given ACE’s commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we generally look for charities whose direction and strategic vision are aligned with that goal. A well-developed strategic vision must be realistic to manage and execute. It is likely the result of well-run, formal strategic planning; when a charity’s leaders regularly engage in a reflective strategic planning process, revisions and improvements to the charity’s strategic vision are likely to follow.

Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-composed board?

Bruce Friedrich is GFI’s co-founder and Executive Director. He has a long history of animal advocacy and an interest in effective altruism, and he is largely responsible for setting the strategy and tone of the organization. Based on our conversations with GFI staff members129 and a survey we sent out this year, we feel that Bruce has quickly earned respect and admiration from GFI’s staff.

GFI’s five-person board includes Bruce Friedrich, GFI’s co-founder and Executive Director, as well as Kathy Freston, an author of vegan books, and Stewart David, a retired accountant and management consultant who has served on the audit committees of several national nonprofits. David is now board chair and Director of GFI’s audit committee. The remaining two Board Members are affiliated with Mercy For Animals (MFA), which helped found GFI. These are MFA Founder and Board Member Milo Runkle and MFA’s former general counsel, Vandhana Bala.130

According to U.S. best practices, nonprofit boards should be comprised of at least five people who have little overlap with an organization’s staff or other related parties.131 There is only weak evidence that following these best practices is correlated with success, and if they are correlated, that may be because more competent organizations are more likely to both follow best practices and to succeed—rather than because following best practices leads to success. Still, we find it concerning that several of the Board Members have significant ties to Friedrich and to MFA. We worry that Friedrich’s views could frequently go unchallenged, since he is affiliated with several Board Members132 and serves on the board himself.

While GFI’s Board Members have relevant occupational backgrounds, we are concerned about their potential lack of occupational and viewpoint diversity. In particular, the evidence for the importance of board diversity is somewhat stronger than the evidence recommending board sizes of five or greater, in large part because there is some literature indicating that team diversity generally improves performance.133 However, to our knowledge, the evidence of the impact of board diversity on organizational performance is less strong than the evidence of the impact of team diversity.134

GFI sends all strategic documents, monthly reports, and quarterly goals and outcomes to all Board Members for feedback.135

Does the charity have a well-developed strategic vision?

Does the charity regularly engage in a strategic planning process?

GFI reevaluates their strategic plan annually and they do so in a manner that allows for significant input from all nine department Directors and their teams.136 The majority of their strategic planning is done via drafting and editing a strategic plan document on which all staff are invited to comment. While staff members mostly work on the sections of the plan related to their own department, they are welcome to edit other sections as well. The board is also given access to this document.137 Every department also prepares quarterly goals and assesses the previous quarters’ goals and outcomes; this is a time in which each department asses their strategy and makes adjustments as needed.

Does the charity have a realistic strategic vision that emphasizes effectively reducing suffering?

GFI’s mission is to create “a healthy, humane, and sustainable food supply.”138 They have told us that they want to replicate the successes of plant-based milk alternatives with cellular and plant-based alternatives to meat, using the power of markets and food technology to provide alternatives to animal agriculture.139 We believe that achieving this aim could lead to immense benefits for animals.

GFI’s vision of developing plant-based and cellular alternatives to animal products has the potential to reduce farmed animal suffering on a large scale. Despite their short track record, we have some evidence that they choose effective opportunities to help animals within this field.140 GFI also attempts to support other work on plant-based and cellular alternatives to animal products by guiding startups, analyzing legal challenges, and drawing in bioengineering talent.141

Does the charity’s strategy support the growth of the animal advocacy movement as a whole?

Given their focus on plant-based and cellular alternatives to animal products, much of GFI’s work does not have a direct bearing on much of the animal advocacy movement, although they are contributing to a neglected and potentially high-impact area. Their work is largely aimed at supporting plant-based foods and commercial cellular agriculture, including by supporting startups, publishing analyses of regulatory challenges, and raising awareness of cellular agriculture among scientists and advocates.

GFI encourages and facilitates collaboration within the plant-based and clean meat industry.142 We believe that, when done well, such collaborative work contributes meaningfully to the growth of a potentially valuable section of the animal advocacy movement—specifically, by limiting mistakes and redundancy and by building the capacity of those working in this shared domain. GFI’s leadership believes that their work does indeed complement the work of other animal advocacy groups who advocate for diet change. That’s because, in their view, GFI attempts to make diet change advocacy more likely to be successful by helping to create the products that will allow people to make those diet changes much more easily.

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Effective charities are generally well-managed on an operational level; they should have healthy cultures and sustainable structures. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about their human resources policies and their perceptions of staff morale. We also speak confidentially with non-leadership staff or volunteers at each charity to solicit their perspectives on the charity’s management and culture.143 Finally, we send each charity a culture survey and request that they distribute it among their team on our behalf.144, 145

Does the charity have a healthy culture?

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly towards all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. One important part of acting responsibly towards stakeholders is protecting employees from instances of harassment and discrimination in the workplace. Charities that have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, since varied points of view improve a charity’s ability to respond to new situations.146 A healthy charity is transparent with donors, staff, and the general public and acts with integrity; in other words, their professed values align with their actions.

In general, GFI’s employees feel highly valued and autonomous in their work. Many appreciate GFI’s relatively “flat” structure; that is, there is not a lot of middle management in the organization. Staff are fairly unanimous that one of GFI’s main strengths is its open communication between all levels of the organization, from the top down as well as the bottom up. They feel comfortable expressing their needs or reporting problems to multiple people in leadership roles.

As GFI has grown, some staff have become concerned about an increased workload, particularly for department Directors. Other staff remain satisfied that GFI is working to meet everyone’s needs, in part through their plans to hire more support staff. GFI’s leadership appears to be aware of the high workload and potential risk of burnout among staff. Friedrich tells us, for example, that GFI’s department Directors have been overburdened with certain logistical details, like booking travel. He reports that they are in the process of shifting responsibilities within the organization in order to “free up our scientists to really do science, and our Directors to really think strategically, and so on.” Still, some staff remain concerned about burnout. They told us that GFI, as an effective altruist organization, can be so focused on cost effectiveness that they don’t invest quite enough in staff salaries, development, and support.

Nevertheless, GFI’s entire staff appears to be united in its investment in GFI’s strategic vision; nearly all survey respondents noted it as one of GFI’s greatest strengths. They generally feel that GFI’s work is important and unique, and the staff seem to take pride in the strategic planning process, noting that they all have the opportunity to contribute.

Does the charity communicate transparently and act with integrity?

GFI seems to communicate openly and honestly with donors, and makes every effort to use donor funds as efficiently as possible. Several GFI employees reported to us that they have never worked for an organization with greater integrity than GFI.

Still, it’s our impression that GFI tries to maintain such tight control over their public image that their public transparency, while quite high, is not as high as it could be. GFI does not list their Board Members online—though they provided a list to us—and some staff noted to us that even they don’t know who the Board Members are or what they do. Several staff noted that GFI does not have a public “mistakes” page as some other effective altruist organizations have, though those staff members indicated that they would support such a page. Perhaps of greatest concern to us is that, during the recent spate of #MeToo controversies in the animal advocacy movement, GFI made only a short and general public statement, without acknowledging its close connections to at least two high-profile and controversial figures in the movement.

However, GFI’s employees are nearly unanimous that transparent internal communication is one of GFI’s greatest strengths. GFI’s leadership has an open-door policy and staff agreed that the leadership welcomes all feedback, including critique. All survey respondents had positive reports for the charity’s internal communication. Many described it as “open,” “respectful,” “compassionate,” and “fun.” There was a general consensus that—at all levels of the organization—when staff make mistakes, they discuss them openly, make appropriate adjustments, and move forward. Moreover, GFI has regular meetings in which staff can anonymously submit any question to Friedrich. These meetings have allowed for internal discussions of controversial topics.

Does the charity provide staff and volunteers with sufficient benefits and opportunities for development?

In general, GFI’s staff seems satisfied with their compensation and benefits. Several staff expressed to us that they happily took pay cuts to work at GFI, out of support for its mission. Some expressed a desire for higher pay, noting that it could improve staff retention. Many staff mentioned a desire for more vacation time, but they felt that the ability to work remotely at least partially compensates for the limited time off.

Some GFI team members identified staff development as an area in which their organization can improve. Some staff take regular courses or trainings that are specific to their roles.147 GFI encourages staff to attend trainings, conferences, and courses, but many reported that they are too busy to take advantage of these opportunities. Still, most agreed that if they expressed a specific need for training or a course, that need would be met.

Does the charity have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion?

Many staff noted in the survey that GFI has internally acknowledged the lack of some kinds of diversity (e.g., racial diversity) on their team, and that they are working to address it. For instance, staff report that GFI’s operations team is working to improve diversity through the hiring process, the organizers of the Good Food Conference made an effort to select a diverse group of speakers, and the organization has been working with Encompass on diversity, equity, and inclusion. We believe that one additional action GFI could take is offering paid internships to provide an entry point to the movement, even for those who cannot afford to work for free.

Despite its lack of racial diversity among staff, there is fairly equal gender representation among GFI’s leadership. Some staff also reported to us that GFI is a safe and supportive workplace for LGBTQ+ individuals and people with children. Moreover, GFI appears to be welcoming of viewpoint diversity; there is general agreement among staff that leadership will consider disparate opinions on anything, and that they take those opinions into consideration when making decisions.

Does the charity work to protect employees from harassment and discrimination in the workplace?

We are not aware of any instances of harassment or discrimination at GFI, though we recognize that there are numerous reasons why we might not be privy to such information if it does exist, and are therefore cautious not to take this lack of information as evidence that GFI is free of any issues with harassment or discrimination. The charity has provided staff trainings in harassment, discrimination, and workplace diversity. Some staff reported to us that, during the early stages of the #MeToo movement, GFI’s leadership proactively emphasized their lack of tolerance for harassment and updated their harassment and discrimination policies. They adopted nearly the same comprehensive policy put forth by Tofurky, and are in the process of implementing an anonymous reporting system.148

One important factor in creating a safe workplace is having systems in place for staff to report problems. According to our culture survey, the vast majority of GFI’s staff feel comfortable bringing up problems or concerns with others in the organization. Many mentioned that they have multiple people to turn to: department Directors, the Executive Director, the chief counsel, and the HR department.

Does the charity have a sustainable structure?

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in which current leadership might move on to other projects. The charity should seem unlikely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, they should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

Does the charity receive support from multiple and varied funding sources?

GFI is entirely supported by grants and donations.149 GFI’s fiscal management strategy is to spend each year what it raised the prior year; this enables them to budget on a rolling 12-month timeframe.150, 151 Overall, we think that while their funding sources are not especially diverse, they do rely on a relatively broad donor base and take a responsible and sustainable approach to their finances. This year, they are increasing their focus on expanding their donor base by reaching out to donors interested in the environmental and health benefits of cultured and plant-based meat.152

Does the charity seem likely to survive potential changes in leadership?

GFI is still young and in almost all respects seems to have been heavily influenced by one person: Executive Director Bruce Friedrich. It’s difficult for us to predict what might happen if GFI underwent a change in leadership. We asked GFI’s employees what they thought about potential leadership changes, and many agreed that Friedrich would be a difficult person to replace. Still, GFI has a number of highly competent department Directors, who already take a large share of responsibility within the organization. Many of GFI’s processes are carefully documented, which would help see them through a transition, and the staff appears to be united in pursuit of their strategic goals.

Questions for Further Consideration

No matter how thoroughly we research a charity, there will always be open questions about some aspects of the charity’s strategy or programming. We’ve asked charities some of those questions, and we present their answers below, without commentary.

Suppose it will take 40, 50, or even 100 years for cultured meat to reach cost-competitiveness. Is there still a strong case that donating to GFI is a cost-effective use of the movement’s resources right now?

GFI’s Response:

“Our own research and cost-of-goods analysis for clean meat is very encouraging, and we believe that clean meat will be cost-competitive with conventional animal meat much sooner than 40 years from now. One of the first analyses that GFI undertook—beginning in the summer and fall of 2016—was determining whether there was a path toward clean meat reaching cost competitiveness within a reasonable timeframe and without relying on technological “moonshots” for which timeframes are exceedingly difficult to forecast. The resulting analysis (available upon request) has focused on the cell culture media as the main input—and thus the main cost driver—of clean meat production. This analysis examines what price points could be expected with conservative assumptions about costs decreasing with scale. It also examines a handful of alternative formulation scenarios with straightforward substitutions of specific high-cost components of the media. Each of these scenarios and price point assumptions are justified using parallels and data points from other industries, including the food industry whenever possible, and/or using data from the scientific literature.

The outcomes and benefits of this analysis were twofold: first, it allowed us to feel confident in continuing to devote resources toward the clean meat industry because this analysis showed that there is a straightforward path for clean meat to cost competitiveness with animal meat and this path is not reliant upon substantial technical advances that do not yet exist. Second, it allowed us to articulate the major pain points in achieving price parity with animal meat; this included identifying the highest-cost components of clean meat production as well as approaches to alleviate those costs. Our analysis has contributed to our understanding of high-value research projects to advance these cost-saving approaches, and it has informed our strategy for reaching out to other industries (such as the life science industry, ingredient and raw material suppliers, chemical suppliers, etc.) to bring in stakeholders that can accelerate progress down the clean meat cost curve.

Second, we point out that there are now almost 30 clean meat companies that are working to build the clean meat market sector. For anyone who wants to accelerate the demise of animal agriculture for the success of clean meat, backing one or more of these companies is a great option if your goal is to make money—that is, if you are looking for an equity investment. But if your goal is to see clean meat commercialized as quickly as possible, supporting open-source science through GFI is one way to help all of the companies—and the entire endeavor writ large—at the same time.

Indeed, we believe that philanthropic support will best accelerate the commercialization of clean meat. GFI donors enable us to launch projects that are beyond the scope of any individual player within the clean meat commercial landscape but that can substantially accelerate R&D and make more efficient use of private capital and resources for ALL companies tackling these challenges.

Third, if it really did take 40 or more years to reach cost competitiveness, it seems likely that most of the current crop of companies would fail, since their investors are expecting commercialization much more quickly. In that case—which again, we do not believe is likely—the work of GFI would be even more important, since we would continue even as profit-driven entreprises did not. GFI and other nonprofits would then become the most important path to reaching clean meat cost competitiveness as quickly as possible. Cutting just a few years off that trajectory would save billions of animals, in addition to the other positive impacts (global health, food security, climate, etc.).

GFI’s network of supporters is helping our SciTech department lay the groundwork from which all companies and scientists can build, our policy department lobby to unlock millions of dollars in government grants for basic and open-source science, our corporate engagement department to inspire the food processing industry to get excited about and invested in clean meat R&D, and our representatives in India, Brazil, China, and Israel to generate public funding and scientific activity in those countries. Without GFI’s critical work, cost-competitive clean meat will take much longer—whether that is relative to five years or relative to 50 years.

Fourth, consider the promise of hybrid plant-based/clean meat products: Before clean meat reaches price parity with conventional meat, companies will achieve price parity by creating hybrid plant-based/clean meat products. For example, if at one point in time clean meat costs $50/kg but it’s incorporated in a product that’s 90% plant protein and 10% clean meat (added for the flavoring and sensory component it provides), companies selling clean meat products will much more rapidly reach price parity with conventional meat.

Finally, if it does turn out that clean meat will require much more time to reach price parity, GFI can shift as much of our focus as we would like to plant-based meat, which is equally important to us and our mission.”

Does GFI directly support work on developing products other than those that could decrease animal product consumption (e.g., promoting alternatives to silk or leather or promoting yeast-based vanillas or flower fragrances)? Why or why not?

GFI’s Response:

“GFI currently focuses primarily on plant-based meat and clean meat because we believe that we can now help animals the most by focusing on farmed animals (who far outnumber animals exploited by other industries). For this same reason, we hope to do more work with eggs. We don’t expect to move beyond farmed animals, since our goal is to help as many animals as possible. GFI will be doing a lot more with sea animals in the coming year and has released a 34-page action paper, “An Ocean of Opportunity: Plant-based and clean seafood for sustainable oceans without sacrifice.”

Some might suggest that technological progress will come eventually, and what matters most in the long run is whether we’ve achieved the social change necessary to use those new technologies to help animals. Why is GFI working to advance technology rather than to shift public attitudes?

GFI’s Response:

“First, we believe that a big part of what is holding back animal liberation as a philosophy is the cognitive dissonance experienced by the 98–99% of Americans who continue to consume industrially-produced animal products. It is very difficult to support liberation for animals and a more inclusive ethic with regard to other species while simultaneously causing abuse through our purchasing decisions. By removing animals from industrial agriculture and, via technological advancements, making it easier for people to choose products that do not cause harm, we are making it easier for people to extend their circle of compassion to animals in a way that is similar to their current compassion for dogs and cats.

Second, there are literally hundreds of groups focused on changing attitudes about animals, but technological change is highly neglected. Worldwide, there are only a handful of organizations working on technological solutions to factory farming, and they are all young. There are far more organizations and resources currently devoted to social change, and those efforts have been going on for much longer.

Finally, it’s worth noting that with nine billion land animals slaughtered annually for food in the U.S. alone and all of them suffering horribly, even if it’s true that “technological progress will come eventually,” causing it to happen as soon as possible will save massive numbers of animals from suffering that is beyond most of our worst imaginings.”

What can GFI do to ensure that consumers will embrace cultured meat?

GFI’s Response:

“GFI sees value in market research and employs a full time consumer research scientist, Dr. Keri Szejda, who has both an M.A. and a Ph.D. in communication. GFI collaborated with Faunalytics on an ACE-funded consumer survey about clean meat and the most appealing framing for the product; we have also conducted multiple surveys focused on identifying the most appealing name for cultured meat. We are conducting research to identify other critical factors in successfully promoting plant-based meat to non-vegetarians, such as ideal packaging and food modifiers (plant-based, vegan, etc.). We share these findings with companies and will encourage their use by companies.”

;Revenue;Assets;Expenses; 2016;$3,590,781;$2,902,278;$688,503; 2017;$4,687,032;$2,929,310;$4,660,000; 2018 (estimated);$7,500,000;$2,929,310;$7,500,000; 2019 (estimated);$9,000,000;$3,379,310;$8,550,000;

,Lower estimate,Upper estimate High Priority,1700000,2400000 Moderate Priority,250000,1350000 Low Priority,60000,1640000

;2016/2017;2017/2018; Science and Technology;$164,171;$410,728; Innovation;$350,082;$322,615; Policy;$115,738;$441,257; Corporate Engagement;$2,266;$179,680; International Engagement;$201;$395,323; Executive and Operations;$59,486;$509,193; Communications;$21,159;$297,457; Development;$68,599;$346,685;

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

See our recent research on the Allocation of Movement Resources.