The Good Food Institute

Archived ReviewThe Good Food Institute (GFI) currently operates in the U.S., Brazil, India, Asia-Pacific region, Europe, and Israel, where they work to increase the availability of animal-free products through supporting the development and marketing of plant-based and cell-cultured alternatives to animal products. They achieve this through corporate engagement, institutional outreach, and policy work. They also work to strengthen the capacity of the animal advocacy movement through supporting research and start-ups focused on alternative proteins. GFI was a Recommended Charity from November 2016 to November 2021. They were recommended again in 2022.

| Primary area of work: | Cultured and Plant-Based Food Tech |

| Review Published: | 2022 |

Archived Version: 2022

What does GFI do, and are their programs promising ways to advocate for animals?

The Good Food Institute (GFI) works to increase the availability of animal-free products through supporting the development and marketing of plant-based and cell-cultured alternatives to animal products. They achieve this through policy work and institutional and corporate vegan outreach. They also help strengthen the animal advocacy movement by supporting research and startups focused on alternative proteins. GFI currently operates in the U.S., Brazil, India, the U.K., Europe, Asia-Pacific, and Israel. Because most of GFI’s spending on programs goes toward animal groups, outcomes, countries, and interventions that we consider high (or very high) priority, we assessed the expected effectiveness of GFI’s programs as very high.

Taking into account their spending, are their programs cost effective?

After analyzing the achievements and costs of GFI’s programs, we assigned each one a cost-effectiveness rating. Of all of their programs, we believe their policy program, GFI Israel, and GFI Asia-Pacific are the most cost effective (rated high). In contrast, we believe their corporate engagement program and GFI India are less cost effective (rated moderate to high).

Overall, we assess the cost effectiveness of GFI’s work as high.

How much additional funding could they use?

We estimate that GFI has room for $5,000,000 of additional funding in 2023 and $5,000,000 in 2024, beyond their current projected revenues in those years. Therefore, we believe that they could utilize a total revenue of up to $55,651,500 in 2023 and $50,251,500 in 2024.

Do we have concerns about their leadership and culture?

We did not detect any significant concerns with GFI’s leadership and organizational culture, and we expect that reported issues will be handled appropriately until successfully addressed. See their comprehensive review for more details.

Why did they receive our recommendation?

The main interventions used by GFI (research, policy work, and corporate outreach) are likely to be highly effective in strengthening the animal advocacy movement and increasing the availability of animal-free products. Additionally, their work to increase the availability of animal-free products seems to be a relatively neglected area. GFI’s work in Asia-Pacific, Brazil, Europe, India, Israel, the U.K, and the U.S. is likely to be particularly effective based on high tractability and high numbers of farmed animals in those countries. We assess GFI’s policy work as very cost effective, and based on our Room for More Funding assessment, they seem to be in a strong position to use additional funding effectively. These efforts are well-aligned with ACE’s philosophical foundation and cause area priorities.

GFI performed very strongly on the Programs, Cost Effectiveness, and Room for More Funding criteria compared to other charities we evaluated. Based on our assessment of their performance on our four evaluation criteria—Programs, Cost Effectiveness, Room for More Funding, and Leadership and Culture—compared to other charities we reviewed this year, we find GFI to be an excellent giving opportunity and recommend them.

The Good Food Institute was one of our Recommended Charities from 2016 to 2020.

Introduction

Each year, Animal Charity Evaluators (ACE) compiles comprehensive reviews of all organizations that agree to participate in our evaluation process. During our evaluation period, our research team thoroughly examines publicly available information and solicits additional materials and information from participating organizations.

This review is the finished product of our evaluation of The Good Food Institute (GFI), and it contains our assessment of their performance on ACE’s four charity evaluation criteria. This review includes four sections that each focus on a separate criterion: (i) an assessment of the effectiveness of a charity’s programs, (ii) a cost-effectiveness analysis of their recent work, (iii) an estimate of their ability to use additional funding effectively, and (iv) an evaluation of their leadership and culture.

Programs

In this criterion, we assess the expected effectiveness of a charity’s programs without considering their particular achievements. (For more information on recent program costs and achievements, see the Cost Effectiveness criterion.) During our assessment, we analyze the groups of animals the charity’s programs affect, the countries in which they take place, the outcomes they work toward, and the interventions they use to achieve those outcomes, as well as how the charity allocates their spending toward different programs. A charity that performs well on this criterion has programs that are expected to be highly effective in reducing the suffering of animals. The key aspects that ACE considers when examining a charity’s programs are reviewed in detail below.

Method

ACE characterizes effective programs as those that (i) target high-priority animal groups, (ii) work in high-priority countries, (iii) work toward high-priority outcomes, and/or (iv) pursue interventions that are expected to be highly effective. This year, we used a scoring framework to assess the effectiveness of charities’ programs on each of these categories: animal groups, countries, outcomes, and interventions.

We scored the priority levels of different types of animal groups, countries, outcomes, and interventions (i.e., categories) using the Scale, Tractability, and Neglectedness (STN) framework; for countries, we also included an assessment of global influence. Members of ACE’s research team individually scored various types in each category using their own percentage weights for STN. We averaged these scores and percentage weights to calculate an overall priority level score for each type. For ease of interpretation, we categorized these scores into priority levels of very low, low, moderate, high, and very high.

We then used information supplied by the charity to estimate the percentage of program funding spent on different types of animal groups, countries, outcomes, and interventions. Using those estimates and our priority level scores, we arrived at a singular program score for each charity, representing the expected effectiveness of their collective programs.

We use the STN framework to prioritize general cause areas and specific animal groups. By using this framework, we aim to prioritize programs targeting groups of animals that are affected in larger numbers,1 whose situation seems tractable, and who receive relatively little attention in animal advocacy. We consider farmed animal advocacy a high priority because of the large scale of animal suffering involved and its high tractability and neglectedness relative to other cause areas. Among farmed animals, we prioritize specific groups, such as farmed fishes and farmed chickens.2

Given the large number of wild animals (there are at least 100 times as many wild vertebrates as there are farmed vertebrates)3 and the small number of organizations working on their welfare, we argue that wild animal advocacy also has potential to be high impact despite its lower tractability.

For more details on how we currently prioritize animals, see this spreadsheet.

The countries and regions in which a charity operates can affect their work. In the case of farmed animal organizations, we use the STN framework to prioritize the countries where organizations work. By using this framework, we aim to prioritize countries with relatively large animal agricultural industries, few other charities engaged in similar work, and in which animal advocacy is likely to be feasible and have a lasting impact. Additionally, we consider global influence as a fourth factor in prioritizing countries.

Our methodology for scoring countries uses Mercy For Animals’ Farmed Animal Opportunity Index (FAOI) for scale, tractability, and global influence.4 However, ACE uses our own weightings for scale, tractability, and global influence, and we also consider neglectedness as a factor. To assess neglectedness, we compare our own data on the number of farmed animal organizations working in each country to the human population (in millions) of that country.

For more details on how we currently prioritize countries, see this spreadsheet.

We categorize the work of animal advocacy charities by the outcomes they work toward. As we do with animal groups and countries, we use the STN framework to prioritize different outcomes. We also consider long-term impacts as an additional factor in our prioritization. As a result of using our framework, we give higher priority to organizations that work to improve welfare standards, increase the availability of animal-free products, or strengthen the animal advocacy movement. We give lower priority to charities that focus on decreasing the consumption of animal products, increasing the prevalence of anti-speciesist values, or providing direct help to animals.

Despite concerns that welfare improvements may lead people to feel better about—and not reduce—their consumption of animal products,5 there is evidence that raising welfare standards increases animal welfare for a large number of animals in the short term and may contribute to transforming markets in the long run.6 Increasing the availability of animal-free foods, e.g., by bringing new, affordable products to the market or providing more plant-based menu options, can provide a convenient opportunity for people to choose more plant-based options. Moreover, efforts to strengthen the animal advocacy movement, e.g., by improving organizational effectiveness and building alliances, can support all other outcomes indirectly and may be relatively neglected.

For more details on how we currently prioritize outcomes, see this spreadsheet.

We sent the selected charities a request for more in-depth information about their programs and the specific interventions they use. We categorize the interventions charities use into 16 types. In line with our commitment to following empirical evidence and logical reasoning, we use existing research to inform our assessments and explain our thinking about the effectiveness of different interventions. We compiled the research about the effectiveness of each intervention type using information from our research library and research briefs. Using the STN framework, we arrived at different priority levels for each intervention category based on the available research.

For more details on how we currently prioritize interventions, see this spreadsheet.

A note about long-term impact

Each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.7 The potential number of animals affected increases over time due to an accumulation of generations. Thus, we would expect that the long-term impacts of an action would likely affect more animals than the short-term impacts of the same action. This year, we included some considerations of long-term impact in our assessment of each outcome and intervention type. Nevertheless, we are highly uncertain about the particular long-term effects of each intervention. Because of this uncertainty, our reasoning about each charity’s impact (along with our diagrams) will skew toward emphasizing short-term effects.

Information and Analysis

Cause areas and animal groups

GFI’s programs focus exclusively on helping farmed animals, which we think is a high-priority cause area.

Countries

GFI’s headquarters are currently located in the U.S, and they have affiliates in Brazil, India, Israel, Asia-Pacific (Singapore), and Europe (Belgium).

GFI mainly develops their programs in the U.S., Israel, the U.K., Brazil, India, Europe, and Asia-Pacific. While based in Belgium, GFI Europe aims to influence Europe on a more general level. While based in Singapore, GFI Asia-Pacific also works in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, South Korea, and Japan. Some of GFI’s work has a more global scope.

| Country | Scale | Tractability | Global influence | Neglectedness | |||

| FAOI Scale data (0–100 range) | FAOI Global Ranking (100% scale) | FAOI Tractability data (36.7–84.9 range) | FAOI Global Ranking (100% tractability) | FAOI Global influence data (0.1–70.6 range) | FAOI Global Ranking (100% global influence) | Human population (in millions) per farmed animal advocacy org | |

| United States | 18.1 | 3 | 80.4 | 14 | 70.6 | 1 | ~1.4 |

| Israel | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ~0.5 |

| United Kingdom | 3.1 | 16 | 80.7 | 12 | 23.2 | 6 | ~0.8 |

| Brazil | 12.3 | 5 | 55.8 | 45 | 26.1 | 4 | ~5.1 |

| India | 55.5 | 2 | 46 | 57 | 7.4 | 23 | ~31 |

| Belgium | 0.5 | 37 | 78.2 | 15 | 20.4 | 8 | ~0.6 |

| Singapore | 0.2 | 53 | 81.7 | 7 | 4.8 | 29 | ~0.7 |

For each country, we report Mercy For Animals’ FAOI data and global ranking (out of 60 countries) for scale, tractability, and global influence. We report these scores alongside the human population per farmed animal advocacy organization in the country (out of a total of 753 organizations, excluding sanctuaries, that ACE is aware of worldwide), which we used to assess neglectedness.

Most of these countries are high priority based on their FAOI data on global influence (U.S., U.K., Belgium, and Brazil), high priority based on their FAOI data on tractability (U.S., U.K., Belgium, and Singapore), and moderate priority based on their FAOI data on scale (India, U.S., and Brazil). Additionally, our assessment suggests that farmed animal advocacy in India and Brazil is highly neglected. Overall, we conclude that most of GFI’s work targets high-priority countries.

Description of programs

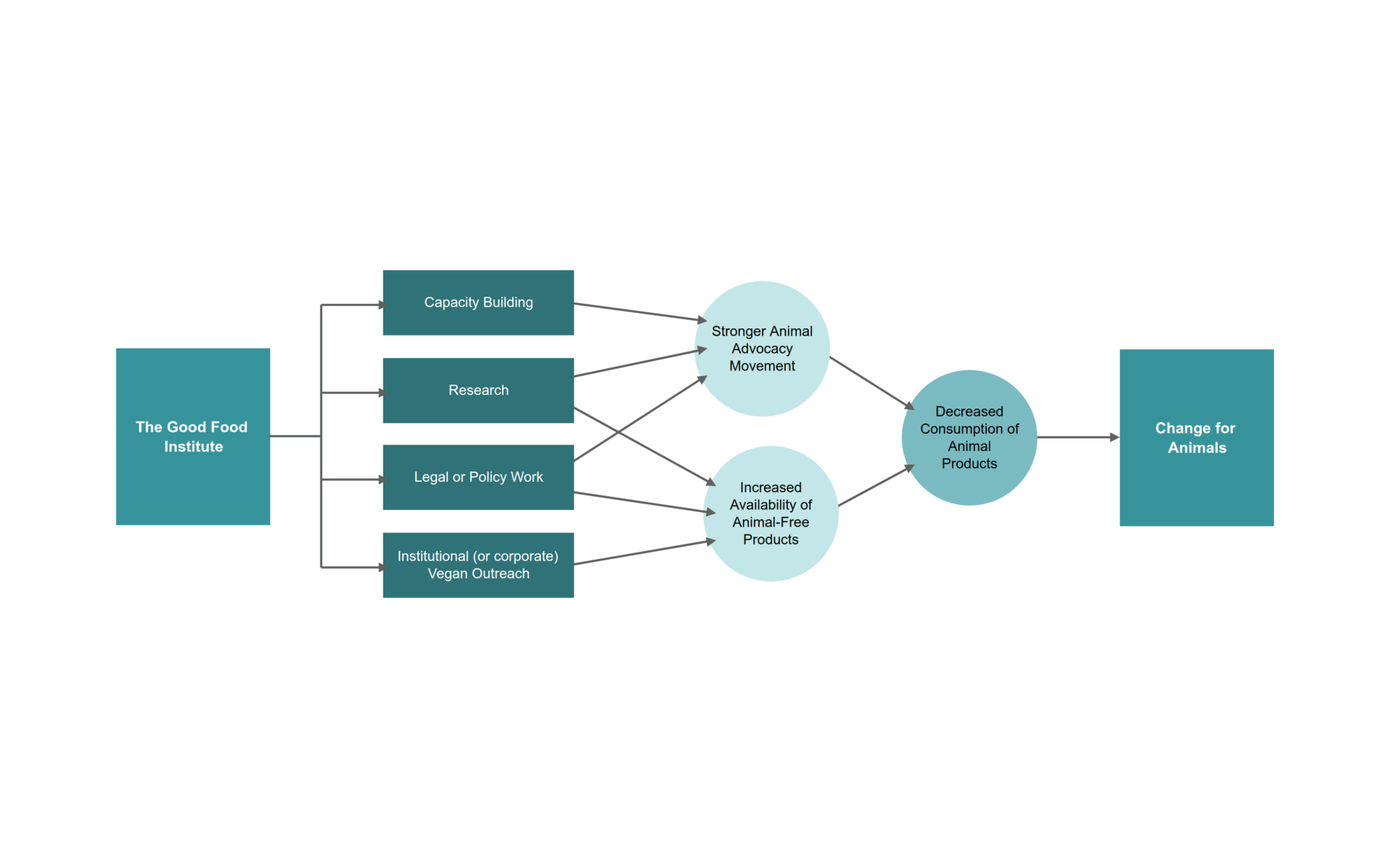

GFI pursues different outcomes to create change for animals. Their work focuses on increasing the availability of animal-free products and strengthening the animal advocacy movement.

We use theory of change diagrams to communicate our interpretation of how a charity creates change for animals. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small or uncertain effects.

Below, we describe each of GFI’s programs and the main interventions they use, listed in order of financial resources devoted to them in the last 18 months (from highest to lowest). Refer to GFI’s general information request and our Cost Effectiveness criterion for more detailed information.

GFI’s programs

This program aims to accelerate the advancement of alternative proteins by conducting and promoting research. Additionally, this program works to build the capacity of the scientific community around alternative proteins and fund research through a grant program.

- Research

- Capacity building

This program focuses on influencing governments to invest in alternative protein research and ensure alternative protein products gain regulatory approval and come to market. Additionally, this program builds the capacity of the movement by educating and engaging NGOs, companies, investors, scientists, and other stakeholders. GFI Europe is based in Belgium (specifically in Brussels), with team members also in the U.K., Germany, France, Austria, and the Netherlands.

- Legal or policy work

- Capacity building

- Media outreach

- Institutional vegan outreach

This program focuses on creating legal and policy change to secure public investments in alternative proteins and advance alternative proteins across Europe by using legislative and regulatory advocacy, litigation, coalition building, and stakeholder engagement. This program focuses on federal and state policy in the United States but also leads an initiative with policy professionals in GFI’s affiliates to influence the Codex Alimentarius (“Food Code”) Commission.

- Legal or policy work

This program focuses on advancing alternative proteins in Israel via research, policy change, and innovation. This program includes increasing the quality and quantity of academic research in the alternative protein field, increasing the number of startups through venture creation and support, and engaging government officials and political leaders toward state support of research funding, infrastructure, and regulatory policies.

- Research

- Legal or policy work

- Capacity building

This program focuses on accelerating alternative proteins in Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, South Korea, and Japan via innovation, public policy change, private sector support, and media engagement.

- Legal or policy work

- Capacity building

- Media outreach

This program focuses on engaging companies to ensure that some alternative protein products are competitive with animal-based products. This program engages investors and financial institutions to direct funding toward the alternative protein sector and engages retailers and commercial foodservice to remove bottlenecks to growth.

- Institutional (or corporate) vegan outreach

- Capacity building

This program focuses on engaging companies, governments, and scientists to increase the availability of alternative proteins in Brazil. In particular, this program provides advice to scientists and producers, engages governmental entities to secure public funding for alternative proteins, and runs a startup and investor network.

- Institutional (or corporate) vegan outreach

- Legal or policy work

- Capacity building

This program focuses on advancing alternative protein development in India through influencing public funding for research and development; reaching out to academia, industry, and government; and supporting emerging companies, entrepreneurs, and investors.

- Legal or policy work

- Institutional (or corporate) vegan outreach

- Capacity building

Research for intervention effectiveness

We categorized the work GFI does into five intervention types: capacity building, legal or policy work, research, institutional (or corporate) vegan outreach, and media outreach. Below, we summarize the most relevant research on the effectiveness of each of these intervention types, listed in order of financial resources devoted to them in the last 18 months (from highest to lowest).

Capacity Building

Capacity building enables organizations to develop the competencies and skills to make their team more effective and sustainable, thus increasing their potential to fulfill their mission and create change.8 ACE’s 2018 research on the allocation of movement resources suggests that capacity building is neglected relative to other interventions aimed at influencing public opinion and industry. Others have argued that many effective animal advocacy organizations could benefit from capacity-building services, specifically from career services and greater diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, especially in the longer term.9

Legal or policy work

Available evidence suggests that legal work by animal advocacy organizations can contribute to changes and modifications in the law, help ensure law enforcement, and motivate cultural shifts in societal attitudes toward animal welfare. The success of this legal work requires that such laws have a positive impact on the welfare of animals and that the work those organizations do contributes to the introduction of those laws. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we expect its effects to be particularly long-lasting.

Research

Conducting research relevant to animal advocacy is a generally promising intervention, especially when considering its potential effects in the longer term. Due to the lack of empirical evidence about the extent to which research results are used by the animal advocacy movement to prioritize and implement their work, our confidence in the short-term effects of this intervention is low. We think the impact of research has a particularly high variance; some research projects can be far more influential than others, and researchers’ rigor seems to be a key factor in their impact. Considering an overview of issues in the research system related to the choice of research questions, the quality and reproducibility of research, and the use of results may be particularly important when determining the impact of research projects.10

Research projects on cell-cultured alternatives that are high quality and have a high potential of being used to develop the industry can be particularly impactful. Although more research is still required to optimize cell-culture methodology11 (and consumer acceptance of cell-cultured food products could still increase), we expect that cell-cultured food will likely cause a considerable decrease in demand for farmed animal products if it reaches price-competitiveness with conventional animal protein. In the longer term, this reduced demand for animal-based products could weaken the animal agriculture industry.12

Research projects on plant-based alternatives that are high quality and have high potential of being used to develop the industry can be particularly impactful. Developing inexpensive, nutritious, and appealing animal product alternatives may make individuals more willing to reduce their animal product consumption.13 Some evidence suggests that increasing the visibility and variety of vegetarian options in food environments decreases meat consumption.14

Institutional (or corporate) vegan outreach

We are not currently aware of any peer-reviewed research on influencing the availability of animal-free products through institutional outreach. However, we could learn from studies that investigate the effectiveness of institutional outreach to hospitals and schools on increasing the availability of “healthy foods” (specifically fruits, vegetables, and whole grains). Reaching out to nonprofit institutions with the effective strategies identified in these studies has the potential to increase the availability of animal-free foods, considering the high participation and success rates in health food outreach to schools and hospitals. Some of these strategies included working with the local hospital association and hospital workers’ unions to encourage participation in the intervention, enlisting in-depth assistance from dietitians, and providing advice on how to incorporate new standards into existing operations.

There is some evidence that increasing the availability of animal-free products in institutions can decrease the consumption of animal products. A literature review concluded that increasing the visibility and variety of vegetarian options in food environments decreases meat consumption.15 The review also suggested that increasing the portion sizes of vegetable dishes in restaurants or canteens (and reducing meat portions) increases vegetable consumption and decreases meat consumption.

Media outreach

An experiment found that reading news articles about farmed animal welfare reduced self-reported animal product consumption in meat-avoiders (e.g., reducetarians, pescetarians, and vegetarians) but not meat-eaters.16 A previous study suggests that media attention to animal welfare has a small but statistically significant impact on meat demand.17

Our Assessment

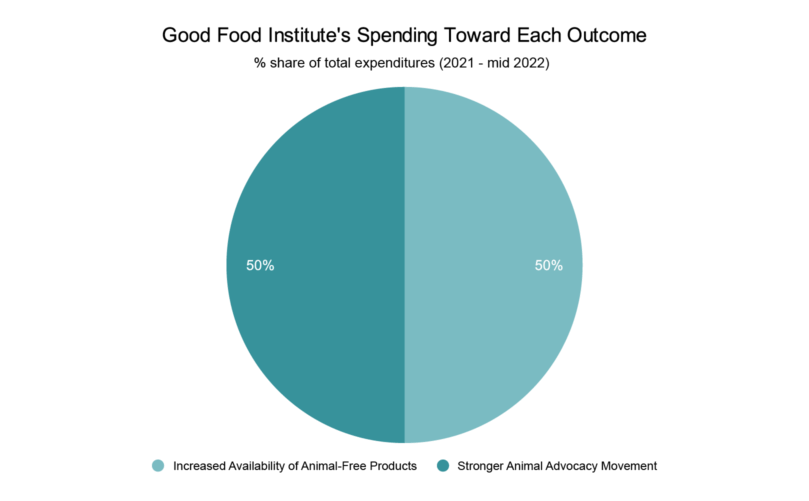

We estimate that all of GFI’s spending on programs targets a high-priority animal group (farmed animals in general). Additionally, we estimate that about half of their spending on programs goes toward a very high-priority outcome (increased availability of animal-free products), and the other half goes toward a high-priority outcome (stronger animal advocacy movement). Most of their programs target high-priority countries (U.S., U.K., Brazil, and Belgium) and use high-priority interventions (capacity building, and legal or policy work).

Overall, we assess the expected effectiveness of GFI’s programs as very high.18

Cost Effectiveness

In this criterion, we assess the effectiveness of a charity’s approaches to implementing interventions, their recent achievements, and the costs associated with those achievements. By conducting this assessment, we seek to gain insight into a charity’s overall impact on animals given the resources they used to achieve their results. A charity that performs well on this criterion likely utilizes their available resources in a cost-effective manner. The key aspects that ACE considers when examining cost effectiveness are reviewed in detail below.

Method

We conducted our analysis by comparing a charity’s reported expenditures over the past 18 months to the reported achievements of their main programs during that time.19 We estimated total program expenditures by taking the charity’s reported expenditures for each program and adding a portion of their nonprogram expenditures weighted by the program’s size. This process allowed us to incorporate general organizational running costs into our consideration of cost effectiveness. During our evaluation, we also verified a subset of the charity’s reported achievements by searching for independent sources to help us verify claims and directing follow-up questions to the charity.

We selected up to five key achievements per program to factor into our cost-effectiveness assessment.20 When selecting achievements, we prioritized those that we thought were most representative of their respective programs and that referred to completed work (rather than work in progress). For each key achievement, we identified the associated intervention type and assigned the respective intervention score. (For more details on how we calculated those scores and prioritized interventions, see the Programs criterion.) Based on the charity’s reported expenditure on each achievement, we computed how many such achievements the charity accomplished per $100,000.21

We used the number of achievements per $100k and other contextual information (e.g., the species affected) to score the cost effectiveness of each key achievement, and then used those scores to modify the average intervention type score. This modified score for each key achievement takes into account how impactful the intervention is on average and how cost-effectively it has been implemented by the charity. The final score for each program is the average of the modified intervention scores, weighted by the relative expenditure on each key achievement.

The final cost-effectiveness score is the average of the program scores, weighted by percentage of total expenditures spent on each program. This score indicates on a 1–5 scale how cost effective we believe this program has been over the last 18 months, with 1 indicating very low cost effectiveness, 2 indicating low cost effectiveness, 3 indicating moderate cost effectiveness, 4 indicating high cost effectiveness, and 5 indicating very high cost effectiveness. Please see the cost-effectiveness assessment spreadsheet for more detailed information.

Below, we report the total program expenditures, key achievements of each program, and estimated cost effectiveness of each program.

Information and Analysis

Overview of expenditures

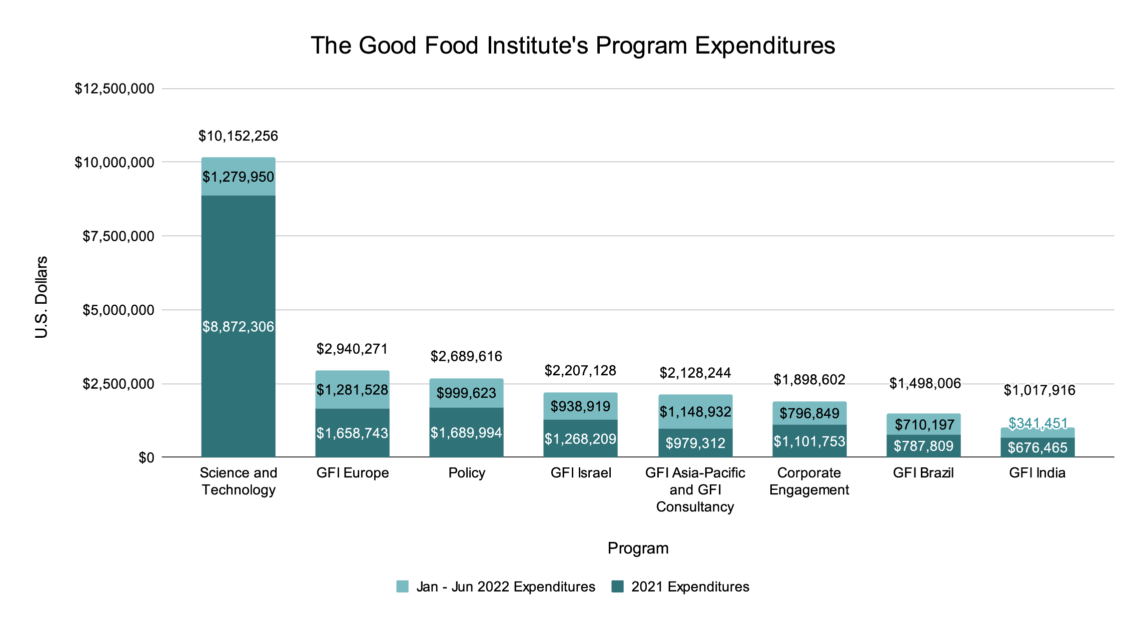

The following chart shows GFI’s total program expenditures from January 2021 – June 2022.

Overview of programs

The following tables show GFI’s key achievements, achievement expenditures, the number of achievements per $100,000, and a program cost-effectiveness score from January 2021 – June 2022.

Program cost-effectiveness score: 3.7

Key achievements:

| Key achievements | Achievement expenditures (USD) | Number of achievements per $100,000 |

| Conducted and released 5 analyses, 3 about cultivated meat and 2 about plant-based meat | $710,658 | 0.7 analyses |

| Funded 37 research proposals, totaling $5.5 million | $7,614,192 | 0.5 research projects funded |

| Gave 45 presentations: 25 industry presentations and 20 conference presentations | $304,568 | 14.8 presentations |

| Launched a resource hub and selected 20 new student groups as part of the Alt Protein Project | $304,568 | 6.6 new student groups |

| Reached a total of 29,578 people with seminars, an online course, and databases geared towards researchers | $304,568 | 9711.5 individuals reached through outreach |

Program cost-effectiveness score: 3.7

Key achievements:

| Key achievements | Achievement expenditures (USD) | Number of achievements per $100,000 |

| Helped influence the U.K. government to commit to investing £120 million into alternative protein research | $117,611 | £106,282,720.2 in investments influenced |

| Onboarded 140 participants from 85 companies into a new initiative to foster global corporate collaboration | $58,805 | 238.1 participants in networking initiative |

| Secured 800 positive media reports about alternative proteins across Europe and launched the GFI Europe website and email newsletter | $147,014 | 544.2 media reports |

Program cost-effectiveness score: 4.8

Please note that the key achievements in this program are not published here in order to preserve confidentiality.

Program cost-effectiveness score: 3.9

Key achievements:

| Key achievements | Achievement expenditures (USD) | Number of achievements per $100,000 |

| Helped launch a consortium of 24 groups working on cultivated meat research, received $18 million in government funding | $132,428 | $13,592,324.5 funding secured |

| Provided guidance to 6 new alternative protein startups | $66,214 | 9.1 companies advised |

| Established an Alternative Protein Science Community of 136 members in academia and industry | $132,428 | 102.7 researchers engaged |

Program cost-effectiveness score: 3.8

Key achievements:

| Key achievements | Achievement expenditures (USD) | Number of achievements per $100,000 |

| Engaged 200 alternative protein researchers through seminars | $63,847 | 313.3 researchers engaged |

| Launched 2 university modules about alternative proteins | $127,695 | 1.6 university modules |

| Worked with 14 governmental and intergovernmental agencies | $212,824 | 6.6 government agencies engaged |

Program cost-effectiveness score: 3.4

Key achievements:

| Key achievements | Achievement expenditures (USD) | Number of achievements per $100,000 |

| Published 7 industry reports and reached 7,449 webinar viewers | $189,860 | 3.7 reports |

| Reached 25,863 people through group events and programs directed at industry participants | $94,930 | 27,244.3 individuals reached through outreach |

| Held 707 one-on-one meetings with food industry stakeholders | $569,581 | 124.1 stakeholder meetings |

| Added 157 new investors to the Investor Directory, bringing the total to 366 | $94,930 | 165.4 investors added to database |

| Launched first open-access fundraising database for alternative proteins, with 7,338 users visiting the page | $37,972 | 19,324.8 users visiting the page |

Program cost-effectiveness score: 3.7

Key achievements:

| Key achievements | Achievement expenditures (USD) | Number of achievements per $100,000 |

| Supported JBS Foods and BRF S.A. to enter the cultivated meat sector | $44,940 | 4.5 corporate partnerships |

| Secured 979 media publications | $59,920 | 1,633.8 media reports |

| Granted official observer status in Codex Alimentarius activities and assembled a Codex Team | $29,960 | 3.3 government certification status |

| Developed a university course, a scientific workshop series, and gave 4 technical lectures | $44,940 | 13.4 courses and lectures developed |

Program cost-effectiveness score: 3.41

Key achievements:

| Key achievements | Achievement expenditures (USD) | Number of achievements per $100,000 |

| The India Smart Protein Innovation Challenge (ISPIC) had 745 participants, and awarded INR 21,000,000 (approx. $263,468) across 20 teams | $40,717 | 1,829.7 participants in innovation challenge |

| Reached 6,134 people with educational webinars | $30,537 | 20,086.8 individuals reached through educational outreach |

| Co-published a report about the alternative protein market in India | $20,358 | 4.9 reports |

| Established the Smart Protein Scientific Forum to facilitate collaboration in the scientific community | $40,717 | 2.5 scientific collaboration group established |

| Secured 362 media publications and presented at 52 events | $50,896 | 813.4 media publications and presentations |

Room for More Funding

A recommendation from ACE could lead to a large increase in a charity’s funding. In this criterion, we investigate whether a charity would be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that a new or renewed recommendation may bring in. Our assessment of this criterion ultimately guides our recommendation decision; charities are ineligible to receive a particular recommendation status if they would be unable to absorb and effectively utilize the subsequent funding. All descriptive data and estimations for this criterion can be found in the RFMF model spreadsheet.

Method

We begin our room for more funding (RFMF) assessment by inspecting the charity’s revenue and plans for expansion through 2024, assuming that their ACE recommendation status and the amount of ACE-influenced funding they receive will stay the same. Then, we outline how the charity would likely expand if they were to receive funds beyond their predicted income and use this information to calculate their RFMF. Finally, we share our thoughts about the charity’s overall financial sustainability and revenue diversity.

Plans for Expansion

To estimate charities’ RFMF, we request their financial records from the past 30 months and ask them to predict what their revenue will be in the next 30 months. We also ask how they plan to allocate funding among their programs. We then assess our level of confidence in their projections based on factors such as past revenue, past expenditures, and nonfinancial barriers to the scalability of their programs (e.g., time or talent shortages).

Although we list the expenditures for planned nonprogram expenses, we do not assess the charity’s overhead costs in this criterion, given that there is no evidence that the total share of overhead costs negatively impacts overall effectiveness.24 However, we do consider relative overhead costs per program in our Cost Effectiveness criterion. Here, we focus on determining whether additional resources are likely to be used for effective programs or other beneficial organizational changes. The latter may include investments into infrastructure and staff retention, both of which we think are important for sustainable growth.

Unexpected Funding

We ask charities to indicate how they would spend additional, unexpected funding that an ACE recommendation may bring in. This amount varies from charity to charity, but on average is roughly $200,000 per year for Standout Charities and $1,000,000 per year for Top Charities. We also ask previously recommended charities to indicate how they would use additional funding because there is some evidence that repeatedly recommended charities are more appealing to donors; therefore, they may get more ACE-influenced funding over time. We then assess our level of confidence in the charity’s ability to carry out their plans in 2023 and 2024—i.e., how much unexpected funding we believe they could utilize for effective programs in that timeframe—to estimate their RFMF for those years. These estimates are then shared with the charity and adjusted as needed based on feedback. Our RFMF estimates are intended to identify the point at which we would want to check in with a charity to ensure that they have used their funds effectively and can still absorb additional funding.

Reserves

We may adjust RFMF based on the status of a charity’s reserves. It is common practice for charities to hold more funds than needed for their current expenses in order to be able to withstand changes in the business cycle or external shocks that may affect their incoming revenue. Such additional funds can also serve as investments in future projects. Thus, it can be effective to provide a charity with additional funding to secure the organization’s stability and/or provide funding for larger, future projects. Therefore, we increase a charity’s RFMF if they are below their targeted amount of reserves. If a target does not exist, we suggest that charities hold reserves equal to at least one year of expenditures.25

Revenue Diversity

The charities we evaluate typically receive revenue from a variety of sources, such as individual donations and grants from foundations.26 A review of the literature on nonprofit finance suggests that revenue diversity may be positively associated with revenue predictability if the sources of income are largely uncorrelated.27 However, there is evidence that revenue diversity may not always be associated with financial stability.28 Therefore, although revenue diversity does not play a direct role in our recommendation decision, we indicate charities’ major sources of income in this criterion for donors interested in financial stability.

Information and Analysis

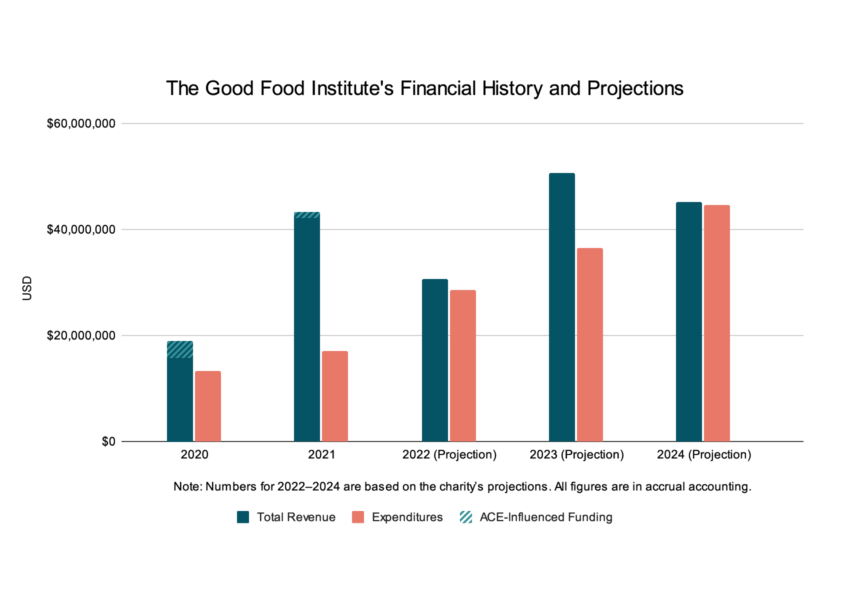

The chart below shows GFI’s revenues, expenditures, and net assets from 2020–2021, as well as their own projections for the years 2022–2024.

Revenue, Expenditures, and ACE-Influenced Funding Over the Years 2020–2024

Plans for Expansion

GFI plans to greatly expand all of their programs, with a 55% increase in total expenditure from 2022 to 2024 and several teams more than doubling in size. We consider this to be ambitious growth relative to other charities we evaluate, which is a potential indicator that successes may not scale due to limiting factors such as operations and leadership’s ability to manage change. It is also possible that recruiting staff with the right skills and/or experience may be challenging, especially in regions where animal advocacy is particularly neglected. However, GFI has demonstrated some success in growing internationally and has committed to benchmarking salaries to fall at or above the 75th percentile for a think tank. Therefore, we have moderate-to-high confidence in their plans below, assuming that they hit their fundraising goals.

Below, we share GFI’s plans for each of their programs in more detail. Projected changes in expenditure are the charity’s own estimates from August 2022. We also include a surface-level assessment of the feasibility of their plans. More details can be found in the corresponding estimation sheet and in the supplementary materials.

| 2021 | 2022 (Projected) | 2023 (Projected) | 2024 (Projected) |

| $6,786,404 | $6,913,939 | $7,951,029 | $9,143,684 |

- Planned expansions and other changes

- Expand research funding activities, especially influencing other funding agencies to prioritize alternative protein research

- Expand from 13 team members in mid-2022 to 21 by the end of 2022, up to 25 in 2023, and 29 in 2024

- Feasibility of plans: moderate to high

- See summary of charity’s overall expansion plans at the start of this section.

- We consider science and technology as one of the charity’s more ambitious program expansions because of the sharp increase in recruitment (based on percentage growth and number of hires).

| 2021 | 2022 (Projected) | 2023 (Projected) | 2024 (Projected) |

| $1,268,768 | $3,023,944 | $3,779,930 | $4,724,913 |

- Planned expansions and other changes

- Hire policy managers in Spain and Italy

- Expand the policy team more broadly to help unlock millions of euros for research and development

- Expand communications team for multilingual coverage of alternative proteins

- Expand science and technology team to include roles relating to community growth and mobilization of research funding

- Feasibility of plans: moderate to high

- See summary of charity’s overall expansion plans at the start of this section.

| 2021 | 2022 (Projected) | 2023 (Projected) | 2024 (Projected) |

| $1,292,672 | $2,470,957 | $2,841,600 | $3,267,840 |

- Planned expansions and other changes

- Hire eight to 10 people to help secure more public research funds, engage more meaningfully with multilateral and nonprofit organizations (including those with global health and climate focuses), and step more fully into their role as a think tank

- Feasibility of plans: moderate to high

- See summary of charity’s overall expansion plans at the start of this section.

| 2021 | 2022 (Projected) | 2023 (Projected) | 2024 (Projected) |

| $970,050 | $1,804,231 | $2,255,289 | $2,819,111 |

- Planned expansions and other changes

- Create alternative protein academic research centers with some of Israel’s leading universities and position Israel’s alternative protein capabilities as a strategic national asset

- Currently hiring two policy managers: one with an international strategic focus and one to advance supportive Israeli government policy, with several upcoming hires to further position Israel as a global leader in the field of alternative proteins. An optimistic scenario could lead the team of 11 to up to 20 staff by the end of 2024.

- Feasibility of plans: moderate to high

- See summary of charity’s overall expansion plans at the start of this section.

| 2021 | 2022 (Projected) | 2023 (Projected) | 2024 (Projected) |

| $749,073 | $1,842,584 | $2,763,876 | $4,145,814 |

- Planned expansions and other changes

- APAC will shift focus towards Southeast Asia

- New affiliate offices in Korea and Japan, with 10 new hires in each

- Feasibility of plans: moderate

- See summary of charity’s overall expansion plans at the start of this section.

- We consider GFI Asia-Pacific (APAC) as one of the charity’s more ambitious program expansions because of the sharp increase in recruitment (based on percentage growth and number of hires) in conjunction with the relative difficulty of recruiting in this region and high percentage increase in projected expenditure.

| 2021 | 2022 (Projected) | 2023 (Projected) | 2024 (Projected) |

| $842,728 | $2,285,052 | $2,627,809 | $3,021,981 |

- Planned expansions and other changes

- Expand from 11 team members to 15 by the end of 2022, 18 in 2023, and 20 and 2024. Highest priority roles are a Manufacturer Engagement Specialist, a Consumer Insights and Research Specialist, an ESG/CSR Analyst, and a Supply Chain Specialist

- Feasibility of plans: high

| 2021 | 2022 (Projected) | 2023 (Projected) | 2024 (Projected) |

| $602,593 | $2,304,794 | $2,880,993 | $3,601,240 |

- Planned expansions and other changes

- Fund more research projects, leverage work in other Latin American countries to influence the region’s political environment, develop a plan for the inclusion of farmers in the alternative protein market, build a legal and safe environment for the development of the cultivated meat market, and develop more technical analyses and innovative studies

- Expand from a team of 18 members to between 23 and 26 by 2024

- Feasibility of plans: high

| 2021 | 2022 (Projected) | 2023 (Projected) | 2024 (Projected) |

| $517,426 | $848,201 | $1,060,251 | $1,325,314 |

- Planned expansions and other changes

- Expand team from nine team members to 20 by early 2023

- Onboard consultants and research fellows for projects that require niche knowledge

- Feasibility of plans: moderate to high

- See summary of charity’s overall expansion plans at the start of this section

Based on our assessment of Cost Effectiveness, we believe that GFI’s science and technology program, corporate engagement program, GFI Brazil, GFI Europe, and GFI India are less cost effective compared to their other programs, as well as some programs at other charities that we consider to be highly impactful. Looking forward to 2023 and 2024, we estimate that about 31% of GFI’s planned expenditures will go toward programs that ACE currently considers to be highly cost effective.

Unexpected Funding

GFI outlined that if they were to spend an additional $200,000 per year, it would be focused on expansion in Asia, particularly their offices in Japan and South Korea, which we believe is an effective and plausible use of funding. Overall, we have high confidence that GFI could effectively absorb at least an additional $200,000 per year beyond their plans for expansion outlined in the previous section.

GFI outlined that if they were to spend an additional $1,000,000 per year, it would be focused on expansion in Asia, funding more opportunities through their research grant program, and increasing investment in research on consumer sentiment about alternative proteins. We believe this is an effective and plausible use of funding. Overall, we have high confidence that GFI could effectively absorb at least an additional $1,000,000 per year beyond their plans for expansion outlined in the previous section.

Reserves

With more than 100% of their current annual expenditures held in net assets—as reported by GFI for 2021—we believe that they hold a sufficient amount of reserves compared to their target of 100%.

Revenue Diversity

GFI receives the majority of their income (over 94%) from grants/donations. In 2021, they received 24% of their funding from donations larger than 20% of their annual revenue. They also received restricted gifts to support activities such as their research grant program, but it did not exceed 20% of total donations.

Our Assessment

Based on (i) our assessment that they have sufficient reserves and (ii) our assessment that they could effectively absorb an additional $1,000,000 and continue to scale beyond that point (based on past levels of expenditure and ability to manage new hires), we believe that overall, GFI has room for $5,000,000 of additional funding in 2023 and $5,000,000 in 2024. These two figures represent the amount beyond their projected revenues of $50,651,500 and $45,251,500 in 2023 and 2024, meaning that we believe that they could utilize a total revenue of up to $55,651,500 and $50,251,500.29 Additionally, we believe that 31% of that funding would contribute to programs that ACE considers to be highly cost effective. See our Cost Effectiveness criterion for our assessment of the effectiveness of their programs.

It is possible that a charity could run out of room for more funding more quickly than we expect, or that they could come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we expect. If a charity receives a recommendation as Top Charity, we check in mid-year about the funding they’ve received since the release of our recommendations, and we use the estimates presented above to indicate whether we still expect them to be able to effectively absorb additional funding at that time.

Leadership and Culture

The way an organization is led affects its organizational culture, which in turn can impact the organization’s effectiveness and stability.30 In this criterion, our main goal is to assess whether organizations seem to have leadership and culture issues that are substantial enough to affect our confidence in their effectiveness and stability. The key aspects that ACE considers when examining leadership and culture are reviewed in detail below.

Method

We review aspects of organizational leadership and culture by examining information provided by top leadership staff (as defined by each charity) and by capturing staff perspectives via our culture survey. At a charity’s request, we also distribute the survey to volunteers working at least five hours per week.

Assessing leadership

First, we consider key information about the composition of leadership staff and the board of directors. There appears to be no consensus in the literature on the specifics of the relationship between board composition and organizational performance.31 Therefore, we refrain from making judgments on board composition. However, because donors may have preferences on whether the Executive Director (ED) or other top executive staff are board members or not, we note when this is the case. For example, BoardSource recommends that, if the law permits, the ED (or equivalent) should be an “ex officio, non-voting member of the board.”32 In this way, the ED can provide input in board meeting deliberation and decision making, at the same time avoiding perceived conflicts of interest, questions concerning accountability, or blurring the line between oversight and execution.

We also consider leadership’s commitment to transparency33 by looking at available information on the charity’s website, such as key staff members and financial information. We require organizations selected for evaluation to be transparent with ACE throughout the evaluation process. Although we value transparency, we recognize that some organizations may be able to have a greater impact by keeping certain information private. For example, organizations and individuals working in some regions or on particular interventions could be harmed by publicizing certain information about their work.

In addition, our culture survey asks staff to identify the extent to which they feel that leadership competently guides the organization. We also ask leadership what strategies they use to learn about staff morale and work climate.

Finally, we have specific considerations for charities that work internationally. We think it’s important that charities, especially those from more-developed countries that have expanded to less-developed countries, address and try to prevent power imbalances. These power imbalances—i.e., differences between more- and less-developed countries’ autonomy and decision-making abilities—can occur within the same organization or between organizations working together. We think it’s important that charities’ leadership create opportunities for their subsidiaries to influence decision-making at the international level.34 We ask leadership to elaborate on their approach to international expansion and report the measures they take to address potential power imbalances.

Organizational policies and workplace culture

We ask organizations undergoing evaluation to provide a list of their human resources policies, and we solicit the views of staff (and volunteers, if applicable) through our culture survey. Administering our culture survey to all staff members is an eligibility requirement to be recommended by ACE as a Top or Standout Charity. However, ACE does not require that all individual staff members at participating charities complete the survey. We recognize that surveying staff and/or volunteers could (i) lead to inaccuracies due to selection bias and (ii) may not reflect employees’ true opinions, as they are aware that their responses could influence ACE’s evaluation of their employer. In our experience, it’s easier to assess issues with an organization’s culture than it is to assess its strength. Therefore, we focus on determining whether there are issues in the organization’s culture that have a negative impact on staff productivity and wellbeing.

We assume that staff in the nonprofit sector often have multiple motives or incentives: They receive monetary compensation, experience social benefits from being part of a team, and take pride in their organization’s achievements for a cause.35 Because nonprofit wages are typically lower than for-profit wages, our survey asks all staff about wage satisfaction. In cases where volunteers respond to our culture survey, we typically ask organizations to provide their volunteer hours, because due to the absence of a contract and pay, volunteering may indicate special cases of uncertain work conditions. Additionally, we request the organization’s benefit policies regarding time off, health care, training, and professional development. We also consider how many of our listed policies (13 general policies and eight REI and harassment/discrimination policies) charities have in place.36 While certain policies might be deemed priorities,37 we do not assess which specific policies from our list are most important for charities to have. Additionally, we make exceptions for charities working in regions where these policies are not common practice.

To capture whether the organization also provides non-material incentives, e.g., goal-related intangible rewards, our culture survey includes the 12 questions from the Gallup Q12 employee engagement survey. We consider an average engagement score below the median value of the scale a potential concern.

ACE believes that the animal advocacy movement should be safe and inclusive for everyone. Therefore, we collect information about policies and activities regarding representation, equity, and inclusion (REI). We use the term “representation” broadly in this section to refer to the diversity of certain social identity characteristics (called “protected classes” in some countries).38 Additionally, we believe that in most countries, effective charities must have human resources policies against harassment39 and discrimination40 and that cases of harassment and discrimination in the workplace41 should be addressed appropriately.42 When cases of harassment or discrimination from the last 12 months are reported to ACE by current or former staff members or volunteers, we assess whether the charity appropriately addressed those cases. We do this by considering staff perceptions of whether the reported cases were handled appropriately. If confidentiality permits, we also ask leadership how they addressed the situation.

Information and Analysis

Leadership staff

In this section, we list each charity’s Executive Director (or equivalent) and describe the board of directors. We mention this for the purpose of transparency and to identify the relationship between the ED and the board of directors.

- Chief Executive Officer (CEO): Ilya Sheyman, who has been involved with the organization for eight months.

- President and Founder: Bruce Friedrich, who has been involved with the organization for six years.

- Number of board members: Five members, including the President Bruce Friedrich, who is a voting board member. GFI has a policy that aims to avoid any potential conflicts of interest between the President and the board. In addition, board members (including the President) are not eligible to vote on any matter that involves them. The board also holds meetings without the President’s attendance on matters such as his annual performance review.

GFI had a transition in their top leadership team in the previous year. A new position was created, GFI U.S. CEO (originally President, but later changed CEO), to lead all aspects of GFI U.S.’s programmatic and administrative operations. In early 2022, Ilya Sheyman was hired, replacing President Bruce Friedrich in these functions, who has shifted to focus on high-level strategy and relationship building.

Staff perception and feedback

GFI has 140 staff members (full-time, part-time, and contractors), and 124 staff members responded to our survey, yielding a response rate of 89%.

About 95% of staff respondents to our culture survey agree that GFI’s leadership team guides the organization competently. Additionally, GFI leadership conducts an annual confidential staff survey (and two follow-up surveys asking targeted questions) and regular check-ins with employees to learn about staff morale and work climate.

Transparency

GFI has been transparent with ACE during the evaluation process and during other communications with ACE. In addition, GFI’s audited financial documents (including the most recently filed IRS form 990 for U.S. organizations) are publicly available online. A list of board members, a list of key staff members, and information about accomplishments are available on their website. Based on the information that they make publicly available, we assess GFI’s transparency towards the public as very high.

International expansion

GFI has expanded from the U.S. to Asia-Pacific (Singapore), Brazil, Europe (U.K. and Belgium), India, and Israel. Each of GFI’s affiliates is responsible for decision making for local programs. All of GFI’s affiliates are independent organizations that make their own plans and set their own agendas. To ensure strategic cohesion, organizational objectives are developed in collaboration with all affiliates. The Managing Director of each affiliate determines the annual strategic plan for that region, and each team establishes their own goals and plans. We are uncertain whether GFI’s top leadership is aware of any potential power imbalances between the affiliates of more- and less-developed countries.43

Staff satisfaction

GFI has a formal compensation plan to determine staff salaries. Of the staff that responded to our survey, about 89% report that they are satisfied with their wage. GFI offers paid time off, sick days, personal leave, and full healthcare coverage. About 96% report that they are satisfied with the benefits provided. This suggests that on average, staff exhibit a very high satisfaction with wages and benefits. Additional policies are listed in the table below.

General policies

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A formal compensation policy to determine staff salaries | |

| Paid time off | |

| Sick days and personal leave | |

| Healthcare coverage | |

| Paid family and medical leave44 | |

| Clearly defined essential functions for all positions, preferably with written job descriptions | |

| Annual (or more frequent) performance evaluations | |

| Formal onboarding or orientation process | |

| Training and development opportunities for each employee | |

| Simple and transparent written procedure(s) for employees to request further training or support | |

| Flexible work hours | |

| Remote work option | |

| Paid internships (if possible and applicable) |

Staff engagement

The average score among our engagement questions was 6.6 (on a 1–7 scale), suggesting that on average, staff exhibit a very high engagement score.

Harassment and discrimination reports

GFI has staff policies against harassment and discrimination (see all other related policies in the table below). A few staff (1–3 individuals) report that they have experienced harassment or discrimination in their workplace during the last 12 months, and a few (1–3 individuals) report to have witnessed harassment or discrimination of others in that period. In particular, they report fear of retaliation from leadership and a lack of channels to file complaints in the affiliates. All of the claimants reported that the situation was not handled appropriately.

GFI’s leadership team states that they had not been aware of the reports received by ACE and had not received any such reports themselves, but that they are implementing steps to prevent these issues. In particular, they have confirmed that all affiliates either have their own anonymous reporting process or direct their employees to use GFI U.S.’s anonymous reporting hotline. Affiliates have agreed to re-emphasize the availability of these channels with their teams. Additionally, in our previous review of GFI, we noted some concerns with leadership and culture related to both retaliation and a fear of retaliation from top leadership for voicing disagreements at the organization. Since then, leadership has taken a series of actions, such as training staff on how to use the anonymous reporting system, distributing an anonymous survey to staff asking for feedback about their comfort with voicing their opinions without fear of retaliation and using the anonymous reporting hotline, and providing anti-retaliation training to all supervisors and staff. Based on this limited information, our impression is that leadership is working on addressing these situations.

Policies related to representation, equity, and inclusion (REI)

| Has policy |

Partial / informal policy |

No policy |

| A clearly written workplace code of ethics/conduct | |

| A written statement that the organization does not tolerate discrimination on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, or other irrelevant characteristics | |

| A simple and transparent written procedure for filing complaints | |

| Mandatory reporting of harassment and discrimination through all levels, up to and including the board of directors | |

| Explicit protocols for addressing concerns or allegations of harassment or discrimination | |

| Documentation of all reported instances of harassment or discrimination, along with the outcomes of each case | |

| Regular trainings on topics such as harassment and discrimination in the workplace | |

| An anti-retaliation policy protecting whistleblowers and those who report grievances |

Our Assessment

We did not detect any major concerns with GFI’s leadership and organizational culture, and we expect that reported cases of harassment or discrimination will be handled appropriately until successfully addressed. We positively note that GFI is transparent toward external stakeholders, has a large number of staff policies, staff generally agree that leadership guides the organization competently, and staff are engaged and satisfied with their job.

Overall Recommendation

The main interventions used by GFI (research, policy work, and corporate outreach) are likely to be highly effective in strengthening the animal advocacy movement and increasing the availability of animal-free products. Additionally, their work to increase the availability of animal-free products seems to be a relatively neglected area. GFI’s work in Asia-Pacific, Brazil, Europe, India, Israel, the U.K, and the U.S. is likely to be particularly effective based on high tractability and high numbers of farmed animals in those countries. We assess GFI’s policy work as very cost effective, and based on our Room for More Funding assessment, they seem to be in a strong position to use additional funding effectively. These efforts are well-aligned with ACE’s philosophical foundation and cause area priorities.

GFI performed very strongly on the Programs, Cost Effectiveness, and Room for More Funding criteria compared to other charities we evaluated. Based on our assessment of their performance on our four evaluation criteria—Programs: very highly effective; Cost Effectiveness: high cost-effectiveness; Room for More Funding: >$1M; Leadership and Culture: no major concerns—compared to other charities we reviewed this year, we find GFI to be an excellent giving opportunity and recommend them as a Top Charity. We expect that all charities that undergo review by us are effective, but GFI is exceptional even within that group.

We don’t consider the number of individuals as the only relevant characteristic for scale, and we don’t necessarily believe that groups of animals or species should be prioritized solely based on scale. However, the number of animals in a group or species is one characteristic of scale that we use for prioritization.

Of the 191 billion farmed vertebrate animals killed annually for food globally, 101 billion are farmed fishes and 79 billion are farmed chickens, making these impactful groups to focus on.

We estimate there are 10 quintillion, or 1019, wild animals alive at any time, of whom we estimate at least 10 trillion are vertebrates. It’s notable that Rowe (2020) estimates that 100 trillion to 10 quadrillion (or 1014 to 1016) wild invertebrates are killed by agricultural pesticides annually.

We acknowledge that using Mercy For Animals’ FAOI scores can bias us toward their own considerations of the most important countries for them to focus on.

On average, our team considers advocating for improvements of welfare standards to be a positive and promising approach. However, there are different viewpoints within ACE’s research team on the effect of advocating for animal welfare standards on the spread of anti-speciesist values. There are concerns that arguing for welfare improvements may lead to complacency related to animal welfare and give the public an inconsistent message—e.g., see Wrenn (2012). In addition, there are concerns with the alliance between nonprofit organizations and the companies that are directly responsible for animal exploitation, as explored in Baur and Schmitz (2012).

For arguments supporting the view that the most important consideration of our present actions should be their long-term impact, see Greaves & MacAskill (2019) and Beckstead (2019).

Bianchi et al. (2018) suggests that restructuring physical micro-environments could help to promote lower demand for meat.

For more detailed information, see GFI’s Programs Assessment spreadsheet.

As part of our information request to charities, we ask for a list and description of their main achievements for each of their programs. We also asked charities to report their expenditures for each program, and to estimate the percentage of program expenditures spent on each key achievement.

Assessing cost effectiveness by looking at a charity’s key achievements has limitations. It will likely bias cost-effectiveness estimates upward to some extent, as it does not consider expenditures on less impactful achievements or work that did not result in an achievement. This may affect larger programs more, as their key achievements are more likely to account for a smaller proportion of overall program costs and thus may be less reflective of the program’s overall cost effectiveness.

We standardized to achievements per $100,000 to allow for easier comparisons across achievements.

We use ratings of low, moderate, and high to help distinguish between the performance of charities that we review, and to make our numerical scores easier to interpret. These qualitative ratings are not reflective of a charity’s performance when compared to other charities that were not selected for review.

Please see our GFI’s Cost Effectiveness Assessment spreadsheet for more detailed information.

National Council of Nonprofits (n.d.); Propel Nonprofits (2022); Boland (2021)

To be selected for evaluation, we require that a charity has a budget size of at least about $100,000 and faces no country-specific regulatory barriers to receiving money from ACE.

These numbers may be revised upwards if inflation continues at rates comparable to those seen in 2021 to 2022. GFI noted that official inflation-based COLA adjustments to salaries were 5.9% for 2022 and 8.7% for 2023 in the U.S., with a similar rate of inflation expected in a number of places where they operate, including Europe, Brazil, and Singapore.

Rousseau (1990), cited in Kartolo et al. (2022)

BoardSource (2016), p. 4

Charity Navigator (n.d.-a) defines transparency as “an obligation or willingness by a charity to publish and make available critical data about the organization.”

Clark and Wilson (1961), as cited in Rollag (n.d.)

Our evaluation process for human resources policies uses a assessment system that we have adapted from Charity Navigator (n.d.-b).

Examples of such social identity characteristics include: race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender or gender expression, sexual orientation, pregnancy or parental status, marital status, national origin, citizenship, amnesty, veteran status, political beliefs, age, ability, and genetic information.

Harassment may occur in one incident or many, and incidents can be nonsexual or sexual in nature. ACE defines nonsexual harassment as unwelcome conduct—including physical, verbal, and nonverbal behavior—that upsets, demeans, humiliates, intimidates, or threatens an individual or group. ACE defines sexual harassment as unwelcome sexual advances; requests for sexual favors; and other physical, verbal, and nonverbal behaviors of a sexual nature when: (i) submission to such conduct is made explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment; (ii) submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual is used as the basis for employment decisions affecting the targeted individual; or (iii) such conduct has the purpose or effect of interfering with an individual’s work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

ACE defines discrimination as the unjust or prejudicial treatment of or hostility toward an individual on the basis of certain social identity characteristics.

ACE defines the workplace as any place where work-related activities occur, including physical premises, meetings, conferences, training sessions, transit, social functions, and electronic communication (such as email, chat, text, phone calls, and virtual meetings).

ACE recognizes that a lack of reporting does not necessarily mean that there are no issues at an organization, and it may indicate that staff don’t feel comfortable reporting issues.

GFI reports that their mission to feed 10 billion people by 2050 securely, safely, and sustainably is heavily reliant on shifting developing countries to alternative protein sources. As such, GFI has been investing substantially in the growth of affiliates in developing countries, while at the same time slowing the growth of its U.S. operations.

GFI’s leadership reports that they will be implementing paid family and medical leave in January 2023.