The Humane League

Archived Review| Review Published: | November, 2018 |

| Current Version | 2023 |

Archived Version: November, 2018

What does The Humane League do?

The Humane League (THL) engages in a variety of programs designed to persuade individuals and organizations to adopt behaviors that reduce farmed animal suffering. THL’s largest programs, based on their budget, are their corporate campaigns and grassroots organizing. They encourage corporations to enact policies dictating higher animal welfare standards and they educate the public using outreach materials such as leaflets and online videos. Through their grassroots offices and campus leadership program, they recruit and train new animal advocates. THL also works to build the animal advocacy movement internationally through the Open Wing Alliance, which offers funding and training to advocacy groups interested in working on corporate campaigns.

What are their strengths?

In our view, THL’s most significant advantage is not any single program, but rather their general approach to advocacy. Among animal advocacy organizations, THL makes particularly strong efforts to assess their own programs and to look for and test ways to improve them. Their success in their corporate campaigns, and the publication of their research through Humane League Labs (HLL), has shifted the outlook and programming of several other advocacy organizations toward finding the best ways to advocate for animals.

THL’s organizational structure appears to be strong, with a cohesive and democratic culture promoting positive relationships between THL staff, Board Members, and volunteers. We think this is especially important for THL because part of the intention of their local offices is to build a grassroots movement, and setting a positive and results-oriented tone for those new to the movement is good for animal advocacy as a whole. Their track record demonstrates significant success. Recently, they’ve been especially successful with their corporate campaigns, and they appear to have played an important role in promoting corporate campaigns outside of the U.S. by training and collaborating with other groups through the Open Wing Alliance.

What are their weaknesses?

We are somewhat concerned about THL’s sustained high rate of expansion. THL has in the past been remarkably quick to expand in response to increased funding, more than doubling their budget each year in the recent past. Although their growth seems to have slowed this year, they still have the highest projected growth of our Top Charities. It’s possible that they will continue to use large amounts of new funding efficiently, but we also believe there’s a chance that they’re reaching a size where significant changes in organization or internal systems are required, which might put a damper on their growth.

Why did The Humane League receive our top recommendation?

THL has an exceptionally strong commitment to using studies and systematic data collection to guide their approach to advocacy. Their corporate campaigns are especially strong, and they often take the lead in collaborating with other groups to facilitate knowledge-sharing about their strategic approach. They have been flexible in using their grassroots network for a variety of advocacy efforts—including individual outreach, support for corporate campaigns, and grassroots legislative advocacy. We find THL to be an excellent giving opportunity because of their strong programs and evidence-driven outlook, and we are pleased to recommend donating to them.

How much money could they use?

We believe that The Humane League has a total funding gap of approximately $350,000 to $5.3 million, and that they could effectively put to use a total revenue of $10.1 million–$13.4 million.1,2,3 We expect they would use additional funding to continue expanding their National Volunteer Program as well as their international work through the Open Wing Alliance (OWA). We also expect they would continue to build their infrastructure by hiring additional lawyers, media staff, and Web Developers.

What do you get for your donation?

From an average $1,000 donation, THL would spend about $420 on corporate outreach to campaign for higher welfare policies. They would spend about $320 on grassroots outreach, including leafleting, supporting corporate campaigns, and humane education. THL would also spend about $130 on online ads, $100 on communications and social media, and about $30 on studies through Humane League Labs. Our rough estimate is that these activities combined would spare -6,000 to 13,000 animals from life in industrial agriculture.4

We don’t know exactly what THL will do if they raise additional funds beyond what they’ve budgeted for this year, but we think additional marginal funds will be used similarly to existing funds.

The Humane League has been one of our Top Charities since August 2012.

These estimates are based on ACE’s 2018 RFMF Model for The Humane League.

Although the low end of the funding gap estimate is substantially negative, that does not indicate that we think THL is likely to be overfunded—we think they most likely still have significant room for more funding. Because we subtract expected increases in revenue from our total room for more funding, this range estimate was significantly impacted by the large grant that THL was recently awarded from the Open Philanthropy Project (Open Phil). This $10 million grant will be dispersed over 3.5 years, so we estimated that THL will receive $2.86 million next year. They previously received $5 million from Open Phil over the past three years for an average disbursement of $1.67 million per year. We used these two values to estimate that this new grant will amount to an increase in revenue of about $1.2 million for 2019. We will follow up with THL in mid 2019 to check in on their room for funding.

This range is a subjective confidence interval (SCI). An SCI is a range of values that communicates a subjective estimate of an unknown quantity at a particular confidence level (expressed as a percentage). We generally use 90% SCIs, which we construct such that we believe the unknown quantity is 90% likely to be within the given interval and equally likely to be above or below the given interval.

Sometimes our estimated cost-effectiveness ranges include negative numbers if we are not certain that an intervention has a positive effect, and it could have a negative effect, even if we think that isn’t likely. This doesn’t necessarily mean we think those interventions are equally likely to harm animals as to help them.

Table of Contents

- How The Humane League Performs on our Criteria

- Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

- Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

- Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

- Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

- Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

- Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

- Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

- Questions for Further Consideration

- Supplementary Materials

How The Humane League Performs on our Criteria

Criterion 1: Does the charity engage in programs that seem likely to be highly impactful?

Before investigating the particular implementation of a charity’s programs, we consider their overall approach to animal advocacy in terms of the cause(s) they advance and the types of outcomes they achieve. In particular, we consider whether they’ve chosen to pursue approaches that seem likely to produce significant positive change for animals—both in the near and long term.

Cause Area

THL focuses primarily on reducing the suffering of farmed animals, which we believe is a high-impact cause area.

Types of Outcomes Achieved

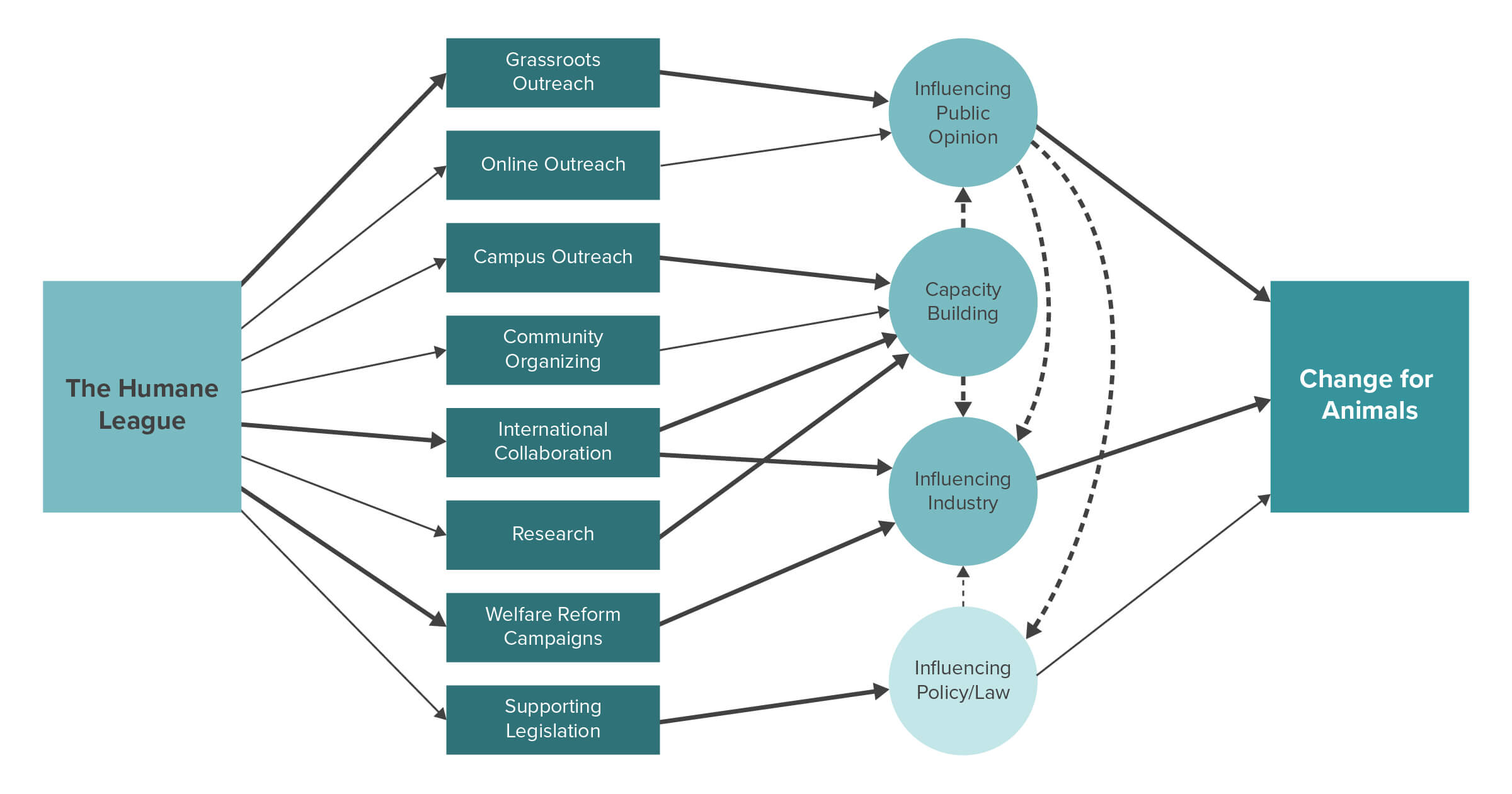

To better understand the potential impact of a charity’s programs, we’ve developed a menu of outcomes that describes five avenues for change: influencing public opinion, capacity building, influencing industry, building alliances, and influencing policy and the law.

THL pursues many different avenues for creating change for animals: they work to influence public opinion, build the capacity of the movement, influence industry, and influence policy and the law. Pursuing multiple avenues for change allows a charity to better learn about which areas are more effective so that they will be in a better position to allocate more resources where they may be most impactful. However, we don’t think that charities that pursue multiple avenues for change are necessarily more impactful than charities that focus on one.

To communicate the process by which we believe a charity creates change for animals, we use theory of change diagrams. It is important to note that these diagrams are not complete representations of real-world mechanisms of change. Rather, they are simplified models that ACE uses to represent our beliefs about mechanisms of change. For the sake of simplicity, some diagrams may not include relatively small and/or uncertain effects.

Influencing Public Opinion

THL works to influence individuals to adopt more animal-friendly attitudes and behaviors through media outreach and grassroots legislative advocacy, which we view as especially promising approaches.1 While it is difficult to measure incremental changes in public opinion—and, consequently, difficult to know when an intervention is more or less successful—we still think it’s important for the animal advocacy movement to target some outreach toward individuals. This is because a shift in public attitudes and consumer preferences could help drive industry changes and lead to greater support for more animal-friendly policies. However, we find that efforts to influence public opinion seem much less neglected than other categories of interventions in the United States.2 While we do not have direct evidence for the situation outside the U.S., we would expect it to be broadly similar to the U.S.

A large amount of THL’s work to influence public opinion is through grassroots outreach. They have grassroots staff in 12 cities in the U.S. as well as in Mexico and the U.K.3 They pursue many methods of influencing public opinion, including tabling events with virtual reality (VR) headsets, organizing events with guest speakers and films, organizing food and activity-based meetups, communicating with the press, conducting online outreach through ads, videos, and a new website, which aims to make a transition to a plant-based diet easier,4 and distributing leaflets.5 We’re unsure about the impact of many of these efforts to influence public opinion (such as leafleting, which we estimate may be less cost effective at creating short-term impact than some other interventions). While our 2017 Leafleting Intervention Report failed to find compelling randomized controlled trial evidence for its short-term impact, leafleting may still serve other, more long-term purposes—such as general awareness raising, contributing to gradual changes in perspective and habits,6 and providing an easy way for some people to get involved in animal activism.

Capacity Building

We see THL’s recruitment on college campuses, activist trainings, and animal advocacy research as especially effective forms of capacity building.7 Working to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement can have far-reaching impact. While capacity-building projects may not always help animals directly, they can help animals indirectly by increasing the effectiveness of other projects and organizations. Our recent research on the way that resources are allocated between different animal advocacy interventions suggests that capacity building is currently relatively neglected compared to other outcomes, such as influencing public opinion and industry.

THL works to build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement internationally as well as in the U.S. They share their knowledge and experience with other groups to improve corporate outreach strategy abroad, particularly through the Open Wing Alliance (OWA), which they founded. In addition to sharing strategy and offering training, THL also helps OWA member organizations around the world to grow through a grant program.8 In 2018, the OWA held its second annual global summit, with participants from animal advocacy organizations from a reported 43 countries coming together to share training, strategy, and tactics.9

Another way in which THL builds the capacity of the movement is by recruiting, mobilizing and training activists.10 Through outreach events, education, protests, and work parties, THL works to help build effective animal advocacy skills among activists to strengthen the capacity of the movement.11 THL also trains advocates through their National Volunteer Program as well as on college campuses through their Campus Outreach Program. The National Volunteer Program allows them to train and support remote activists, who can then be more effectively mobilized in areas where THL doesn’t have staff. The Campus Outreach Program provides training and leadership development for college students with a goal of helping them create self-sustaining animal advocacy clubs on campus. Since these student activists may develop valuable skills and continue working in the animal advocacy movement in the long term, we believe that campus organizing is a potentially high-impact intervention.

THL has continued to expand their research division, Humane League Labs, which is conducting research on online engagement, diet change, and the economics of animal advocacy; we believe this may help animal advocates increase their impact.12 Because the field of animal advocacy research is young and could potentially yield strategies that would improve the efficacy of work in these areas, we consider this research to have significant capacity-building potential. Such research can play a pivotal role in how successful a movement can be. A group might expertly carry out a particular intervention, but if that intervention isn’t effective (or if it has negative effects), then the group is not as impactful as they could be. They may even unintentionally cause net harm. By investigating the effectiveness of interventions and publishing their findings, THL may be able to increase the impact of advocacy groups. If THL’s findings inform other groups’ work, they may over time achieve quite a high impact for a low cost.

Influencing Industry

THL works with corporations to adopt better animal welfare policies and to ban particularly cruel practices in the animal agriculture industry. Though the long-term effects of corporate outreach are yet to be seen, we believe that these interventions have a high potential to be impactful when implemented thoughtfully.13

THL works to get corporations to implement welfare reforms through large, nationwide pressure campaigns. They have been able to utilize their large grassroots network of volunteers in conjunction with their staff in grassroots offices around the country to apply coordinated pressure through protests, media, and petitions against corporations such as Hardee’s, Carl’s Jr.,14 and McDonald’s15 for buying chickens who are bred and killed in particularly cruel conditions. THL also works around the world to achieve cage-free commitments and has been successful with some of the largest food companies in the U.S., the U.K., Japan, and Latin America.16 Through their support of the OWA and in collaboration with other advocacy groups around the world, they have helped achieve cage-free commitments in more countries than one charity could feasibly operate.17 THL has also started working on similar campaigns for chickens raised for meat and they have recently secured commitments from some of the largest producers in the U.S. and abroad.18

Influencing Policy and the Law

THL works to encode animal welfare protections into law through grassroots legislative advocacy, which we think may be especially effective at creating change.19 We think that encoding protections for animals into the law is a key component in creating a society that is just and caring towards animals. While legal change may take longer to achieve than some other forms of change, we suspect its effects to be particularly long-lasting.

THL previously worked to support the successful passage of legislation on confinement practices in Massachusetts20 and, at the time of this writing, they are working to support the Prevent Cruelty California initiative by helping collect signatures to get Proposition 12 on the ballot. They are currently planning “get out the vote” activities to support its passage.21 We think that legislative changes to improve welfare are likely to have an impact on a large number of animals, and are more likely to be followed through on than similar corporate campaigns.

Long-Term Impact

Though there is significant uncertainty regarding the impact of interventions in the long term, each charity’s long-term impact is plausibly what matters most.22 The potential number of individuals affected by a charity increases over time due to both human and animal population growth, as well as an accumulation of generations of animals. The power of animal charities to effect change could be greater in the future if we consider their potential growth as well as potential long-term value shifts—for example, present actions leading to growth in the movement’s resources, to a more receptive public, or to different economic conditions could all potentially lead to a greater magnitude of impact over time than anything that could be accomplished at present.

Predictions about the long-term impact of any intervention are always extremely uncertain, because the effects of an intervention vary with context and are interdependent with concurrent interventions—with neither of these interactions being constant over time.23 When estimating the long-term impact of a charity’s actions, we consider the context in which they occur and how they fit into the overall movement. Barring any strong evidence to the contrary, we think the long-term impact of most animal advocacy interventions will be net positive. Still, the comparative effects of one intervention versus another are not well understood.24 Because of the difficulties in forecasting long-term impact, we do not put significant weight on our predictions.

In the long term, one promising aspect of THL’s work is their emphasis on supporting the animal advocacy movement by cooperating with other charities.25 This year, they introduced a more formal strategic planning process that includes setting goals, metrics, and plans for assessment.26 If this improves the efficiency and success of their operation, it could have important long-term impacts. THL’s National Volunteer program, Campus Outreach program, and their work with the OWA have the potential to grow the animal rights movement by bringing in new people and by helping smaller organizations to grow. The long-term impact of some of this work, such as getting corporations to commit to welfare reforms in the future, remains to be seen —since we don’t know how well corporations will comply, how much work enforcement will take, or how public opinion will be affected.

We’re generally optimistic that obtaining corporate welfare commitments will lead to improvements in welfare in the long term,27 reduce consumption of animal products via price increases,28 and raise awareness of the terrible welfare conditions on factory farms.29 However, some evidence suggests that welfare will not be significantly improved in cage-free systems and that in some ways the situation for hens may be worse, particularly in the transition from caged systems to cage-free systems.30, 31 Some animal advocates worry that marketing eggs and other animal products as “humane” may obscure the suffering and exploitation these purchases support. For some consumers, this may contribute to a belief that animals aren’t harmed in the production of “humane” products, which, some argue, could make subsequent efforts to reduce consumption of animal products more challenging.32, 33

Criterion 2: Does the charity have room for more funding and concrete plans for growth?

In order to recommend a charity, we need to assess the extent to which they will be able to absorb and effectively utilize funding that the recommendation may bring in. Specifically, we need to consider whether there may be non-monetary “bottlenecks,” or barriers to the charity’s growth. First, we look at the charity’s recent financial history to see how they have dealt with growth over time and how effectively they have been able to utilize past increases in funding. Next, we evaluate the charity’s room for more funding by considering existing programs that need additional funding in order to fulfill their purpose, as well as potential new programs and areas for growth. It is important to determine whether any barriers limiting progress in these areas are solely monetary, or whether there are other inhibiting factors—such as time or talent shortages. Since we can’t predict exactly how any organization will respond upon receiving more funds than they have planned for, our estimate is speculative, not definitive. It’s possible that a charity could run out of room for more funding sooner than we expect, or come up with good ways to use funding beyond what we have suggested. Our estimates are intended to indicate the point at which we would want to check in with a charity to ensure that they have used the funds they have received effectively and are still able to absorb additional funding.

Recent Financial History

Last year, we estimated that THL could use an additional $600,000 to $4 million34 in funding above their estimated 2017 budget of $4.5 million. THL has seen large increases in their revenue over the past couple of years, due in part to several large grants from The Open Philanthropy Project (Open Phil)35 alongside some other large donations.36 This has allowed them to expand significantly, both in the U.S. and internationally.

The chart below shows THL’s recent revenues, assets, and expenditures.37

Planned Future Expenses

While grassroots work still forms a large part of THL’s strategy, they have been shifting their strategy for expansion from opening local grassroots offices towards increased investment in their National Volunteer Program.38 Similarly, THL is continuing to expand their international work without opening additional offices abroad and instead partnering with other organizations through the OWA.39 With each of these shifts comes a need for more administrative level staff. THL is also planning to hire additional staff, including a second lawyer, a media person, and a few additional Web Developers.40 THL’s research division, Humane League Labs, is currently hiring for a Research Associate to expand some work on diet change and the economics of animal advocacy.

Assessing Funding Priority of Future Expenses

A charity may have room for more funding in many areas, and each area will likely vary in its potential cost effectiveness. In addition to evaluating a charity’s planned future expenses, we consider the potential impact and relative cost effectiveness of filling different funding gaps. This helps us evaluate whether the marginal cost effectiveness of donating to a charity would differ from the charity’s average cost effectiveness from the past year. We break down the total room for more funding into three priority levels, as follows:

High Priority Funding Gaps

Our highest priority is funding activities or programs that we think are likely to create longer-term impact in a cost-effective way, as well as programs which we have relatively strong reasons to believe will have a highly positive short- or medium-term direct impact in a cost-effective way.41

As described in Criterion 1, THL has a number of programs that we consider promising, including campus outreach, their work with the OWA, research, activist trainings, legislative campaigns, and corporate welfare campaigns. Of these programs, we estimate they could effectively use the largest increases in funding for their work with the OWA.42 In terms of staffing, THL reported a need for additional legal, media, web-development, and corporate outreach staff.43 We agree with their assessment that they could benefit from staff increases in these areas and we think they have the potential to build the capacity of the organization and increase the impact of some of their promising programs. Following a market analysis of salaries, THL is planning to increase salaries to be more competitive—if THL is able to increase their salaries, this may help them to compete with the for-profit sector to attract and retain the most highly skilled staff.44 We estimate that THL has a high priority funding gap of $1.7 million–$3.6 million for 2019.45, 46, 47

Moderate Priority Funding Gaps

It is of moderate priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively moderate marginal cost effectiveness.

Based on THL’s spending for the first six months of 2018, we estimate that their expenses for online outreach will have increased about 21% in 2018 over their expenses for 2017. We used this growth rate along with a consideration of possible staffing increases to estimate that THL has a moderate priority funding gap of $170,000–$850,000 for 2019.48

Low Priority Funding Gaps

It is of low priority for us to fund programs which we believe to be of relatively lower marginal cost effectiveness, or to replenish cash reserves. Because it is likely that there may be future expenditures we haven’t thought of, we also include in this category an estimate of possible additional expenditures (based on a percentage of the charity’s current yearly budget).

THL did not express any plans to expand leafleting so we don’t anticipate a significant expansion of this program in 2019. We considered this along with a range of 1%–20% of their projected 2018 expenses to estimate that THL has a low priority funding gap of $150,000–$1.7 million for 2019.49

The chart below shows the distribution of THL’s gaps in funding among the three priorities:50

After years of rapid growth, THL has put into place additional structures—such as an expanded development staff and a financial manager—in order to be able to sustain further growth.51 While acknowledging a limit to the amount of additional funding they could use within their own organization, THL reports that they could potentially put to effective use a larger sum through their granting program with the OWA.52 THL aims to raise around $8 million in 201853 and $8.9 million in 2019.54 We estimate that next year they have a total funding gap of approximately $350,000 to $5.3 million,55 and that they could effectively put to use a total revenue of $10.1 million–$13.4 million.56

Criterion 3: Does the charity operate cost-effectively, according to our best estimates?

THL runs several programs; we estimate cost effectiveness separately for a number of these programs, and then combine our estimates to give a composite estimate of THL’s overall cost effectiveness.57 We generally present our estimates as 90% subjective confidence intervals. We think that this quantitative perspective is a useful component of our overall evaluation because we find quantitative models of cost effectiveness to be:

- One of the best methods we know for identifying cost-effective interventions58

- Useful for making direct comparisons between different charities or different interventions59

- Useful for providing a foundation for more informative cost-effectiveness models in the future

- Helpful for increasing our transparency60

That said, the estimates of equivalent animals spared per dollar should not be taken as our overall opinion of the charity’s effectiveness. We do not account for some programs that have less quantifiable kinds of impact in this section, leaving them for our qualitative evaluation. For programs that we do include in our quantitative models, our cost-effectiveness estimates are highly uncertain approximations of some of their short-term costs and short- to medium-term benefits. As we have excluded more indirect or long-term impacts, we may underestimate the overall impact. There is a very limited amount of evidence pertaining to the effects of many common animal advocacy interventions, which means that in some cases we have mainly used our judgment to assign quantitative values to parameters.

We are concerned that readers may think we have a higher degree of confidence in this cost-effectiveness estimate than we actually do. To be clear, this is a very tentative cost-effectiveness estimate. It plays only a limited role in our overall evaluation of which charities and interventions are most effective.61

Corporate Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 THL will spend about 43% of their budget, or $2.8 million, on corporate outreach.62 This results in some companies adopting new policies, and these likely result in reduced suffering for animals. We estimate that THL’s corporate campaigns will help cause 56–90 policy changes, affecting 10–320 million laying hens and broiler chickens each year.63

Individual Outreach

We estimate that in 2018 THL will spend about 32% of their budget, or $2.1 million, on individual outreach.64 This will include 400,000–650,000 leaflets being distributed, and 4,500–7,000 people being given humane education presentations.65

Online Ads

We estimate that in 2018 THL will spend about 13% of their budget, or $870,000, on online ads.66 The ads are placed on Facebook, and clicks lead viewers to pro-veg and pro-animal content. We estimate that they’ll get 20 million–32 million clicks on their ads in 2018, at a rate of 20–40 clicks per dollar.67

Communications

We estimate that in 2018 THL will spend about 10% of their budget, or $680,000, on communications.68 We estimate this will result in 45 million–65 million engagements with their social media, and 350–450 features in other forms of media, globally.69

Research

We estimate that in 2018 THL will spend about 2% of their budget, or $150,000, on their research program Humane League Labs.70

Budget Changes Since 2017

The following chart shows the ways in which THL’s budget size and allocation has changed since 2017.

All Activities Combined

To combine these estimates into one overall cost-effectiveness estimate, we translate them into comparable units. This introduces several possible sources of error and imprecision. The resulting estimate should not be taken literally—it is a rough estimate, and not a precise calculation of cost effectiveness.71 However, it still provides some useful information about whether THL’s efforts are comparable in cost effectiveness to other charities’.72

We use our leafleting cost-effectiveness estimate and some aggregated staff estimates to estimate that THL spares between -2 and 0.2 animals from life on a farm per dollar spent on individual outreach, and -0.2 and 0.2 animals from life on a farm per dollar spent on online ads.73, 74 Even though the range estimated for individual outreach extends further into negative values than positive values, we think that overall the impact of THL’s individual outreach is more likely net positive for animals.75

We consider multiple factors76 to estimate that THL spares an equivalent of between -10 and 40 animals per dollar spent on corporate outreach.77, 78

We exclude social media and research results from our final cost-effectiveness estimates and don’t attempt to convert them into an equivalent animals spared figure; our estimates for the number of animals this may impact were too speculative to include here.

We weight our estimates by the proportion of funding THL spends on each activity; overall, we estimate that in the short term—after excluding the effects of some of their programs—THL spares between -6 and 13 farmed animals per dollar spent.79, 80 This equates to between -2 and 7 years of farmed animal life spared81 per dollar spent.82, 83, 84 Because of extreme uncertainty about even the strongest parts of our calculations, we feel that there is currently limited value in discussing these estimates further. Instead, we give weight to our other criteria.

Criterion 4: Does the charity possess a strong track record of success?

To evaluate a charity’s track record, we consider how well the charity has executed previous programs. We also consider the extent to which these previous programs caused positive changes for animals. Information about a charity’s track record helps us predict the charity’s future activities and accomplishments—information that cannot always be incorporated into the criteria above. An organization’s track record can be a pivotal factor when our analysis otherwise finds limited differences in other important factors.

Have programs been well executed?

THL was founded in 2005 and has engaged in their current programs for several years. They have undergone substantial growth in recent years, and a lot of their major successes have occurred more recently. They have a substantial track record of carrying out their programs, working with OWA partners, and training new staff.

Their most successful campaigns over the last few years have been in corporate outreach, particularly their cage-free campaigns. In 2016, after significantly expanding their campaign staff, THL reported their efforts contributed to over 100 cage-free commitments from dining companies, restaurants, manufacturers, and retailers in the United States.85 They also started work on improving broiler welfare in 2017, and now report obtaining at least six commitments in 2016 and 45 commitments in 2017.86 They are currently focusing on attempting to get a commitment from McDonald’s.87 Their recent expansion into the U.K. and Mexico has also led to several cage-free commitments being made,88 and we think it’s likely they’ll achieve the same for Japan over the coming years. THL reports that the’ve made more progress in the U.K. than they expected they would.89 They also report that the OWA has had success in terms of convincing 10 of the world’s 15 largest egg-purchasing manufacturers to produce cage-free policies.90

THL’s corporate outreach program contributed to a major achievement in 2016: they played a part in United Egg Producers (UEP) pledging to eliminate the practice of culling male chicks.91, 92 Note that this welfare reform might have happened without animal advocacy involvement if it had proven to be cost-effective for egg producers. There is room for concern over the pledge’s wording, specifically as it requires implementation “by 2020 or as soon as it is commercially available and technologically feasible.” The language seems open to interpretation and may be easy for UEP to circumvent.93 That said, it’s our view that the threat of a campaign gives THL significant leverage to demand that UEP replace culling with in ovo sexing, even if it proves to be more expensive.

In late 2016, THL launched the Open Wing Alliance (OWA), an international coalition of organizations aiming to end cage confinement practices globally.94, 95 THL provides support to members both with training and tactics intended to assist them in launching campaigns in their own countries, and by issuing grants to member organizations.96 The OWA enables campaigns that simultaneously target international corporations in many of the countries where they operate. These campaigns have resulted in commitments from tens of corporations, many of which operate in hundreds of countries.97 THL is directly responsible for the creation of the OWA, and without their organizational capability and experience in campaigning, the OWA would likely not have seen the success it has.98

THL continues to engage in grassroots outreach, particularly on college campuses.99 They conduct humane education and recruit and train student interns and campus coordinators. They will be taking on 58 students in 2018 to train at a summer retreat.100 In 2017, THL reported that their volunteers and staff distributed over a million leaflets or veg starter guides,101 and that they trained over 700 individuals through an effective activism presentation, amongst other activities.102 They have also increased the numbers of their online volunteers through their Fast Action Network, increasing from about 7,000 members in 2017103 to over 11,000 in 2018.104 Finally, THL reports that tens of millions of people were exposed to factory farm footage as a result of their online outreach.105

Have programs led to change for animals?

The commitments made due to THL’s corporate outreach campaigns will likely affect a large number of animals if they are implemented. As these commitments are not legally binding, it will be especially important to follow up with companies to ensure they are adhered to. THL has begun following up with companies, and they are working with Mercy For Animals to produce a shared database of commitments.106 They believe that ensuring corporate pledges are enforced will be a major project for them in coming years, and they plan to carry it out in part by running campaigns against companies that renege on their commitments.107 Since several of the commitments obtained by THL have deadlines in the early-to-mid 2020s, we may soon have a better understanding of how many companies meet their deadlines. We estimate that their corporate policy victories will reduce the suffering of 10–320 million laying hens and broiler chickens each year once they have been implemented.108

While THL’s direct impact cannot be tracked in campaigns co-led with other organizations, we think they have had enough successes attributable solely to their own impetus that we are confident their corporate campaign program is operating successfully. They conducted many of their cage-free campaigns either independently or in a leadership role, and United Egg Producers’ pledge to end chick culling was made after “exclusive conversations with The Humane League.”109 THL’s role as the organizer and leader of the OWA has allowed them to extend their success further by improving the effectiveness of organizations operating in different regions from them, which we consider to be evidence of the significant impact they have had in the movement.110

Many of THL’s programs attempt to influence individual behavior, and the impact of these is difficult to measure. Included in this category are online ads, leafleting and other literature distribution, and humane education. Humane League Labs’ studies may also work to inform the movement as a whole about how effective these interventions are; however, there have been concerns over the quality of their past research,111, 112 and thus their effect on improving THL and other organizations’ work is uncertain.

Research so far suggests that some of these non-HLL activities have a positive effect, although we remain uncertain as to the effects of leafleting.113 Our 2017 Leafleting Intervention Report indicated that leaflets seem relatively ineffective; we estimate that, in the short term, they produce a near-zero expected change in years of farmed animal lives averted per dollar. Therefore, the many leaflets THL has handed out could have quite limited impact on animals. We expect that online ads may be more effective, and we’re uncertain about the effectiveness of humane education relative to leaflets. However, such outreach could have helped bring about institutional change and could have been an important part of building the farmed animal advocacy movement to what it is today.

Criterion 5: Does the charity identify areas of success and failure and respond appropriately?

A charity that has systems in place for assessing their programs is better equipped to move towards their goals effectively. By conducting self-assessments, a charity can retain and strengthen successful programs, and modify or end those that are less successful. When such systems of improvement work well, many stakeholders benefit: benefactors are inclined to be more trusting and more generous, leadership is able to refine their strategy for achieving their goals, and nonhuman animals benefit more.

To evaluate how well the charity adapts to successes and failures, we consider: (i) how the charity has assessed their past programs and (ii) the extent to which the charity updates their programs in light of those assessments.

Does the charity actively assess areas of success and failure?

THL appears to have a strong commitment to recognizing and responding to success and failure. They set specific and relevant goals, evaluate their programs based on research, and have made changes based on these assessments.

For each of their campaigns, THL judges success by considering a list of relevant, concrete goals.114 They also appear to have an organizational commitment to SMART goals.115 THL reports that they set time-bound goals for smaller-scale outcomes and individual projects,116 such as their 2018 goal to have 38 new broiler welfare policies secured in the U.S. and U.K.117 In addition to being time-bound, they are relevant to THL’s overall mission, fairly specific and measurable, and appear plausibly achievable based on the success of U.S. cage-free campaigns.118 THL has previously shared some short-term goals for their programs in Mexico,119 which are similarly designed but also include milestones indicating what THL believes to be meaningful increments of success.120 These milestones allow THL to better measure partial success at achieving their goals.

THL’s operation of Humane League Labs (HLL) in particular suggests a commitment to evaluating effectiveness. In 2016, HLL released a statement of their commitments, including a commitment to improved research practices and to revising and reanalyzing their research. They recently completed reanalyses of several past studies they conducted in previous years,121 with a priority on those that have drawn public interest, including criticism.122 As the latest iteration of HLL has a short track record, it makes it difficult to predict the extent to which they will provide high-quality, relevant research in the future. Nonetheless, we are encouraged to see HLL commit to strong research principles and revisit past work in light of these principles. In the past, HLL seemed to have difficulty releasing their findings on their planned schedule—findings that also drew some criticism.123, 124 THL recently hired an economist to work with HLL,125 and they are also in the process of hiring a Research Associate. We hope that these new hiring developments will help them to achieve the high-quality research they have been preparing for.

THL’s recent actions and plans to hire more HLL staff suggest that they are currently more willing to put more resources towards HLL. However, the willingness to do so is only valuable insofar as there is high-quality research to learn from.

Still, we are encouraged to see that HLL recently began setting more specific timelines for their research projects as their plans have become more developed.126 HLL appears to have changed considerably in the past couple of years, and their current work includes two highly relevant research projects.127 One of these two projects aims to look at consumption changes in response to a combination of individual outreach interventions. Past studies of individual outreach effects have generally relied on self-reported consumption—which is likely to be somewhat inaccurate128—and HLL aims to achieve substantially greater statistical power relative to previous studies of individual outreach methods.129 This suggests that THL intends to use research from HLL to better understand the effectiveness of some farmed animal advocacy interventions. In fact, THL tells us that they plan to take this study’s results into account when deciding how much to spend on individual outreach.130 Overall, we are encouraged that THL makes a concerted effort to assess and understand their impact, and believe that they will be willing to shift their focus appropriately upon learning more about the effectiveness of different types of advocacy techniques.

Does the charity respond appropriately to areas of success and failure?

We are aware of several recent cases in which THL has changed their programming in response to indicators of success and failure. Because of a lack of evidence supporting the effectiveness of leafleting, THL reports they have focused more of their grassroots efforts on institutional campaigns.131 On a smaller scale, they have changed their approach to several programs—such as their cage-free corporate campaigns in Mexico—based on evidence that their original approach was not succeeding.132 Since movement-building seems to be valuable for whichever other advocacy efforts turn out to be effective, they are also putting more attention towards evaluating and improving their volunteer programs’ effect on getting people engaged in the animal advocacy movement.133 To that end, they tell us that they are working to track their volunteers’ commitment to and level of activity with THL in a more quantitative way.134

They tell us that they are flexible and ready to shift strategies if needed. For example, if corporations don’t implement promised reforms and enforcement campaigns aren’t successful, THL may need to shift towards a legal approach to ensure enforcement.135

Criterion 6: Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-developed strategic vision?

A charity is most likely to be effective if it has a well-developed strategic vision and strong leadership who can implement that vision. Given ACE’s commitment to finding the most effective ways to help nonhuman animals, we generally look for charities whose direction and strategic vision are aligned with that goal. A well-developed strategic vision must be realistic to manage and execute. It is likely the result of well-run, formal strategic planning; when a charity’s leaders regularly engage in a reflective strategic planning process, revisions and improvements to the charity’s strategic vision are likely to follow.

Does the charity have strong leadership and a well-composed board?

David Coman-Hidy has been the President of THL since 2013 and has overseen its significant expansion in the U.S. and internationally. Our impression is that Coman-Hidy is a capable leader and that he has surrounded himself with equally capable colleagues, such as Executive Vice President Andrea Gunn.

THL’s board includes Mark Middleton (chair), who works in the technology industry; Denise Tremblay, a retired university financial manager; and Lydia Chaudhry, who served in a volunteer role as THL’s operations support and volunteer coordinator since 2009 but stepped down in early 2016. Recently, THL has brought on a fourth Board Member: Neysa Colizzi, who has a background in training, facilitating, and corporate consulting. THL is currently seeking a fifth Board Member.136

According to U.S. best practices, nonprofit boards should be comprised of at least five people who have little overlap with an organization’s staff or other related parties.137 However, there is only weak evidence that following these best practices is correlated with success, and if they are correlated, that may be because more competent organizations are more likely to both follow best practices and to succeed—rather than because following best practices leads to success. We think THL’s four-person board—including one person with a long history at the organization—is a minor cause for concern.

THL’s board does not have term limits. We have at times been concerned that the relatively stable composition of THL’s board could prevent the organization from adapting, or could fail to meet the needs of the organization as it grows.138, 139 Moreover, a long-standing board can also have benefits—such as avoiding drifting from the core organizational values.

THL’s board appears to have a reasonable amount of occupational diversity. The evidence for the importance of board diversity is somewhat stronger than the evidence recommending board sizes of five or greater, in large part because there is some literature indicating that team diversity generally improves performance.140 However, to our knowledge, the evidence of the impact of board diversity on organizational performance is less strong than the evidence of the impact of team diversity.141

The board is most involved in the budget-setting process, although THL’s President also meets with them three times a year to discuss the organization’s current status.142 In the annual budget-setting process, THL’s board establishes major goals and plans for the next year and allocates resources for accomplishing those goals.143

Does the charity have a well-developed strategic vision?

Does the charity regularly engage in a strategic planning process?

In previous years, THL’s strategic planning process was fairly informal. Their leadership team met in person every few months to discuss their progress and their plans for the next few months.144 This year, however, THL has taken a more formal approach to strategic planning. In addition to their three-year plan, THL’s leadership team worked with consultants to draft a formal strategic document with quarterly goals and subgoals for each department, along with metrics intended to measure progress.145 They plan to review their progress quarterly and revise their plans semi-annually.146

Does the charity have a realistic strategic vision that emphasizes effectively reducing suffering?

THL has told us that their mission is to end the abuse of animals raised for food.147 They have also told us that their “endgame” is to encode animal protections into law.148 THL’s efforts to self-evaluate and respond to evidence also indicate a commitment to effectiveness.149 Given their mission and their history of conducting evidence-supported interventions, we expect THL to remain committed to effectively helping animals.

Does the charity’s strategy support the growth of the animal advocacy movement as a whole?

THL aims to bring their resources and expertise to animal advocates in many countries, particularly those where the movement is relatively small. Through the OWA, they have shared tools with and trained advocates at many organizations, and provided grants and support to individual advocates in countries with few animal advocacy organizations.150 They have developed resources that they share freely with OWA member organizations, including a corporate outreach campaign manual and a guide to pressure campaigns.151

THL also pursues grassroots efforts that build the capacity of the animal advocacy movement. These efforts include their campus leadership program, their volunteer and intern programs in cities with grassroots offices,152 and their National Volunteer Program.153 They see these programs as a way for THL to contribute to the long-term growth of the movement, rather than just a way to grow their own organization.154 THL has also told us that they aim to have their corporate outreach campaigns complement those of other organizations, and they have worked to coordinate their campaigns with other organizations’ campaigns in the past.155

Overall, THL carries out a number of programs which seem likely to support the growth of the animal advocacy movement in meaningful ways.

Criterion 7: Does the charity have a healthy culture and a sustainable structure?

Effective charities are generally well-managed on an operational level; they should have healthy cultures and sustainable structures. We collect information about each charity’s internal operations in several ways. We ask leadership about their human resources policies and their perceptions of staff morale. We also speak confidentially with non-leadership staff or volunteers at each charity to solicit their perspectives on the charity’s management and culture.156 Additionally, we distributed a culture survey to most of the charities we evaluated in 2018, though we give charities the option of sending us the results of a recent internal survey instead of using the one we provide. THL elected to send us a summary of the results from the survey they distributed to their staff between late March and early April of 2018.157

Does the charity have a healthy culture?

A charity with a healthy culture acts responsibly towards all stakeholders: staff, volunteers, donors, beneficiaries, and others in the community. One important part of acting responsibly towards stakeholders is protecting employees from instances of harassment and discrimination in the workplace. Charities that have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion seek and retain staff and volunteers from different backgrounds, since varied points of view improve a charity’s ability to respond to new situations.158 A healthy charity is transparent with donors, staff, and the general public and acts with integrity; in other words, their professed values align with their actions.

THL seems to invest heavily in their culture; they have a culture committee, a staff “Culture and Engagement Specialist,” and they regularly distribute surveys to their employees and make changes based on the feedback they receive. Our impression is that THL’s culture is generally friendly and comfortable.

As we noted in our 2017 review of THL, we think that THL’s culture has changed somewhat over time; while at a smaller size, the organization was tighter-knit and had more of a familial or social feel for staff. Now that it is larger, leadership has implemented a number of formal ways of keeping all staff informed of each others’ activities—previously, information spread more organically.159 We find this to be an expected and appropriate adaptation to a larger organizational size.

Does the charity communicate transparently and act with integrity?

To our knowledge, THL communicates transparently with their stakeholders. Their internal communication appears to be transparent as well; they solicit regular feedback from their staff in the form of “check in” surveys, and they share the summarized results of those surveys with the whole team. Their spring 2018 survey indicated that their employees generally feel they are valued and treated with respect.

One indication of THL’s integrity is their consistent willingness to collaborate with other groups that share similar goals. THL tells us they want to be the “ultimate team player;”160 they are willing to be flexible and play whatever role is needed in the movement. In the U.S., they tell us, they often play “bad cop” in corporate campaigns, because other animal charities are available to play “good cop.” Internationally, THL tends to play “good cop” through their Open Wing Alliance.161 We think that their willingness to collaborate with other groups and their flexibility with regard to their tactics demonstrates their genuine commitment to helping animals as effectively as possible. Additionally, the free trainings for other groups that THL provides through the Open Wing Alliance demonstrates THL’s willingness to build capacity within the movement, even at their own expense.162

Does the charity provide staff and volunteers with sufficient benefits and opportunities for development?

According to THL’s spring 2018 culture survey, the majority of THL’s employees are satisfied with their benefits, including health insurance and paid time off. In our view, THL has been willing to experiment with many types of benefits that are not traditionally offered by other charities, like internet reimbursement and unlimited paid time off with a mandated minimum. Staff were more split about the adequacy of their salaries—however, we understand that in the past few months THL has been working with a consultant to ensure that their salaries are (i) competitive with other U.S. nonprofits, and (ii) fair and consistent within the organization.

Training staff, interns, and volunteers is a key part of THL’s strategy of helping to grow the animal advocacy movement by increasing the number of committed, trained animal advocates.163 THL has large and structured volunteer, intern, and campus outreach programs designed in part to help participants become better advocates ready for positions of greater responsibility.164, 165 THL also tries to promote professional development among staff through structured training for managers and opportunities to attend relevant conferences and trainings.166 THL tells us that they try to promote from within as much as possible, and we have observed this in several cases.167

THL staff seem to feel that they have opportunities for growth in their current positions and (to a slightly lesser extent) that there is room for career growth and advancement within THL. THL provides opportunities for staff development through providing conferences, webinars, books, articles, and so on. Some staff would like to see further opportunities for development (and in particular, additional funding for attending conferences and training). Still, the majority of respondents to THL’s culture survey indicated that they envision themselves staying at THL in the long term, which we take as a positive sign that they are satisfied with the development opportunities that THL offers.

Does the charity have a healthy attitude towards diversity and inclusion?

THL staff are diverse in terms of national origin, particularly due to THL’s international expansion.168 THL is taking steps to improve staff diversity in terms of other factors, in part by implementing partially blind job applications and posting job listings in a wide range of places. THL also has a staff committee on diversity and inclusion to help educate the organization and provide suggestions for improving THL’s practices.169, 170, 171 THL told us that having diverse voices within the organization helps them respond better to new situations; for example, U.K. team members can provide good suggestions for corporate outreach in Japan because of similarities within corporate culture in those countries that don’t extend to the U.S.172, 173

According to THL’s culture survey, the majority of their staff feels that everyone at THL is treated with respect regardless of race, gender, position, role, department, age, disability, and so on. Most staff also agree that THL has a demonstrated commitment to the value of diversity on its team. Still, several employees noted that while THL has a healthy attitude towards diversity, they would like to further diversify the races and ages of their team.

Does the charity work to protect employees from harassment and discrimination in the workplace?

All THL employees receive harassment training, and all managers receive advanced training..174 In private communication, THL has informed us that they are committed to providing a safe and inclusive workplace and have robust anti-harassment, anti-discrimination, and anti-retaliation policies in place, as well as a clear complaint procedure.. We have heard anecdotal reports of one instance of sexual harassment at THL. We asked THL about this and they informed us that, while they view their process of handling complaints as 100% transparent, the details of any specific complaint or investigation are confidential in accordance with the law and HR best practices. THL tells us that their commitment to confidentiality is essential to protecting the dignity and privacy of the parties involved, and aids in encouraging people to come forward. THL assures us that any complaints of violations of these policies are thoroughly investigated and, if credible, appropriate disciplinary action is taken, up to and including termination.175 It is possible that if other instances have occurred, staff members may have used the confidential reporting system and not reported these incidents to ACE or discussed them publicly. The THL staff with whom we spoke may not be aware of claims that do not involve them, due to the confidential nature of complaints and investigations.

Does the charity have a sustainable structure?

An effective charity should be stable under ordinary conditions and should seem likely to survive any transitions in which current leadership might move on to other projects. The charity should seem unlikely to split into factions and should seem able to continue raising the funds needed for its basic operations. Ideally, they should receive significant funding from multiple distinct sources, including both individual donations and other types of support.

Does the charity receive support from multiple and varied funding sources?

THL is fairly heavily reliant on a small number of large funding sources. In particular, they’ve received several large grants from the Open Philanthropy Project (Open Phil). In 2016, THL received a $1,000,000 grant from Open Phil to support cage-free campaigns, a $1,000,000 grant to be used for international expansion, and a $1,000,000 grant for general support. In 2017, THL received a $2,000,000 grant from Open Phil for support of the OWA over two years. Additionally, an anonymous foundation granted THL $880,000 in 2016 and a total of $1,183,432 in 2017. THL is working to improve their fundraising among smaller donors.176

Does the charity seem likely to survive potential changes in leadership?

THL has strong and effective leadership, a collaborative culture, comprehensive training systems, and a clear strategy. In our view, they have a talented and committed staff with many trained and capable managers. We think they could likely survive a change in leadership.

Questions for Further Consideration

No matter how thoroughly we research a charity, there will always be open questions about some aspects of the charity’s strategy or programming. We’ve asked charities some of those questions, and we present their answers below, without commentary.

Given that the corporate pledges THL campaigns for are non-binding, how can we be sure that they meaningfully support improvements in farmed animal welfare?

THL’s Response:

“When advocacy groups secure policy pledges from corporations, those pledges are not legally binding. As a result, it’s possible that corporations could choose not to honor their pledges. It will likely be the case that animal advocates will need to take some steps to create enforcement mechanisms for these pledges, such as ongoing monitoring with the threat of negative public campaigns if companies don’t comply with their agreements, and ultimately new laws.

We see these pledges as valuable for a few reasons, even though they are not legally binding. The first is that they do appear to drive real change in the standards on farms, as demonstrated by the major shift towards cage-free production following the slew of commitments over the last few years, both in the U.S. and the U.K. (17% and 56% respectively, as of October 2018). This seems to show that egg producers are taking these commitments seriously. We believe that industry publications indicate this too, as they now often discuss how to handle the transition to cage-free. Additionally, we find that these corporate commitments pave the way for the eventual laws that fully ban the production and sale of cage eggs, like the law passed in Massachusetts, the proposition now underway177 in California, and the forthcoming European Union ballot initiative. Lastly, the media conversation and discussion that these campaigns generate are another benefit beyond the improvements that they encourage. We believe that increasing public awareness about the conditions on factory farms while providing an opportunity to speak out is useful in building a movement of advocates and concerned citizens around the world.

In addition to changes in housing for laying hens, the 2016 UEP chick-sexing pledge came after a series of high-profile cage-free victories. The pledge has resulted in a large number of interested parties investing in this research and working to put the new in-ovo sexing technologies in place. We believe that this pledge has greatly accelerated the timeline for adopting this technology and has created favorable coverage for the movement.”

There are some who think that the scale of suffering in the wild is much greater than the scale of farmed animal suffering. What is THL doing to address wild animal suffering?

THL’s Response:

“The number of animals in the wild means that the scale of potential suffering there is extremely high. For now, however, we believe that the greatest opportunity for animal advocates is to work on factory farming because it is a much more tractable issue. As a result, we focus exclusively on ending the abuse of animals raised for food. We hope that changing views on the treatment of farmed animals will lead to greater compassion for all animals, including wild animals.”

Does THL worry that focusing on some of the most extreme confinement practices could lead to complacency with other forms of suffering farmed animals endure or with meat consumption?

THL’s Response:

“The Humane League’s argument on behalf of welfare campaigns can be found here. We feel strongly that incremental victories on behalf of animals build the strength, status, and momentum of our movement, while also resulting in harm reduction for the animals suffering on factory farms. It is very clear to us that a world free from animal suffering starts with a world with less animal suffering.”

There are many more farmed fish than other species of farmed animals. Has THL considered allocating more of their resources towards farmed fish advocacy?

THL’s Response:

“Each year, an estimated 37 billion–120 billion finned fish are slaughtered in the animal agriculture system, compared to roughly 60 billion–80 billion land animals. For this reason, we agree that helping fish is a valuable area that could use much more work.

We have considered this issue and hope to begin working on fish welfare issues in the future, after winning the broiler reform campaign and doing some work to ensure that cage-free commitments are honored. Seeing these campaigns through to completion is our current priority, and we worry that having a third parallel ask of companies would make all of our projects more difficult to complete.

There are also a number of factors making advocacy on behalf of fish difficult, including limited information about what causes the greatest suffering, the many species of farmed fish, and the potentially lower resonance of the issue with the public.

However, we do see fish slaughter reform as a potential target for corporate outreach to improve fish welfare. Mandating less cruel methods of slaughter has been tractable for other species in the past, and should be possible to apply across the fish farming industry. We are considering this as a potential next step for our corporate outreach.”

;Revenue;Assets;Expenses; 2014;$968,246;$715,762;$562,952; 2015;$1,338,136;$1,131,193;$922,705; 2016;$6,575,410;$5,764,167;$1,974,673; 2017;$6,825,478;$8,689,350;$4,398,676; 2018 (estimated);$8,000,000;$9,289,350;$7,400,000; 2019 (estimated);$8,900,000;$9,297,235;$8,892,115;

,Lower estimate,Upper estimate High Priority,1700000,1900000 Moderate Priority,170000,680000 Low Priority,150000,1550000

;2017;2018; Corporate Outreach;$2,187,930;$2,841,190; Grassroots Outreach;$1,070,690;$2,149,470; Online Ads;$620,690;$868,014; Communications;$465,517;$675,385; Research;$155,172;$150,504;

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

See our recent research on the Allocation of Movement Resources.

“The grassroots staff on the ground in 12 U.S. cities (plus Mexico and the U.K.), student organizers on dozens of college campuses, and volunteers in cities and towns across the country are working to inspire long-lasting dietary change.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

“Exposing people to the truth about factory farming and inspiring them to make compassionate food choices is a core part of The Humane League’s work. One way we do this is via targeted Facebook ads in 44 countries. To further this effort, we developed a new website (EatingVeg.org) full of resources, tips, and a short documentary, all aimed at making the transition to a plant-based lifestyle easier.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

For more information on THL’s grassroots outreach, see our Follow-Up Questions for The Humane League, Part Two (2018).

Most people go vegan or vegetarian over a long period (Jabs, Devine and Sobal 1998, p. 199; Beardsworth & Keil 1992; Pfeiler and Egloff 2018; Mullee et al, 2017), with an abrupt ‘conversion experience’ (Beardsworth & Keil 1992) being much less common. The adoption of a politicized dietary identity (such as vegetarianism/veganism) has been found to most commonly occur through a series of encounters (Chuck et al. 2016). Thus, when receiving a leaflet, such experiences may contribute to a gradual shift in perspective. NGOs serve as a primary site of awareness-raising, which is key in achieving widespread societal and political change, particularly in the current climate. Researchers into political change have repeatedly argued that awareness raising is key if we want to change policy (e.g. Basiley et al. 2014). Awareness of reduction motivations does appear to be increasing (Siegrist, Visschers and Hartmann 2015) and awareness may be linked to increased reduction (Lee and Simpson 2016). Leafleting may play a role in this.

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

“In early 2018, The OWA expanded its capacity by adding two staff members and awarding more than $400,000 in grants to 13 member organizations representing 14 countries. These grants will fund Animals International’s expansion into Romania, and Otwarte Klatki’s continued growth in the Ukraine and expansion into Belarus following their tremendous track record in Poland.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

“In March, the OWA hosted its second annual Global Summit to End Cages. One hundred and fifteen advocates from 40 organizations in 43 countries convened in Prague for four days of intensive training and strategic planning.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

For more information on THL’s work to recruit and train activists, see our Follow-Up Questions for The Humane League, Part Two (2018).

“We are mobilizing hundreds of local activists and build up their skills at effective animal advocacy; creating a more robust animal advocate community through regular outreach events; educating thousands of people about factory farming; expanding media coverage of farm animal issues; engaging them in campaign actions like protests and work parties; and reaching even more people with a message of compassion for animals.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

“Our individualized dietary data procurement project, initiated in 2017, continues and we’ve made plans to hire several research assistants to facilitate this work. […] We have successfully hired an economist who is now working to prioritize research questions to explore the economics of animal advocacy and commenced hiring for an additional Research Associate.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

“In 2017 The Humane League staff traveled the U.S. to raise awareness about the cruel treatment of chickens by Hardee’s and Carl’s Jr., and invited tens of thousands of people to take action to demand change. Across the country, The Humane League coordinated days of action, empowered hundreds of volunteers to stand up for animals at protests, amplified our message through media, and inspired hundreds of thousands to add their names to petitions calling for change.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

“The Humane League launched the I’m Not Lovin’ It campaign in coalition with other animal rights groups. Across the country, activists rallied to raise awareness among consumers and expose the truth about McDonald’s animal welfare policy.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

“Humane League campaigners […] secured 13 cage-free commitments in the U.K. to bring the total to 90, including Noble Foods, the U.K.’s largest producer, plus one policy in Ireland. In Latin America, we’ve secured a commitment from Fiesta Foods. And after more than a year of laying groundwork with companies who have never before engaged with an animal protection group, the first Japanese cage-free commitment was released by Seiyo Foods, one of the the country’s largest foodservice companies.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

“OWA has secured 13 global cage-free policies. OWA grantees have also secured over 170 regional cage-free policies.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

“The Humane League worked alongside Open Wing Alliance member L214 in France and international advocates at Compassion in World Farming to secure commitments for sweeping reforms for chickens raised for meat throughout Europe from two major manufacturers, Danone and Nestle.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

In order to best estimate which programs are more or less effective, we collected independent staff judgments of the relative efficacy of every commonly-used intervention and reached a consensus with the following process. Seven research team members rated each type of intervention using a scale from -1 (“relatively ineffective”) to 1 (“relatively effective”), with 0 meaning “not enough information to decide.” The mean score for each intervention was then rounded to the nearest integer to yield a score with which all Researchers were satisfied. As a check, we also calculated the median score and came out with the same results.

THL campaigned at Boston universities, conducted calls, collected signatures, coordinated events, assisted with distribution of campaign signs, and trained volunteers. For more information about the role they played, see our Follow-Up Questions for The Humane League, Part Two (2018).

“The Humane League is contributing to the Prevent Cruelty California initiative. Our staff and volunteers played a key role in successfully qualifying the initiative for the 2018 California Ballot by collecting over 664,00 signatures from November 2017 to April 2018. We are currently planning Get Out The Vote activities to ensure a Yes vote on Proposition 12 on November 6, 2018.” —The Humane League’s Accomplishments (2017–2018)

See Presenting the Long-Term Value Thesis for a more detailed discussion of why long-term impact is what matters most.

“When outcomes of interventions are interdependent, the effectiveness of each is inextricably linked with those of the others. Justifying one as being more effective than another is not quite straightforward—declaring so is often misleading.” —Sethu, H. (2018) How ranking of advocacy strategies can mislead. Humane League Labs.

See our 2018 Leafleting Intervention Report for a more detailed consideration of the potential long-term impact of a particular intervention.

“A big strength is our strategic approach to things. I think we have a history of identifying spaces in the movement where we could fill a niche or add the most value, and we’ve been pretty flexible in going after that thing really aggressively. […] We host summits where we try to get people on the same page strategically. We’ve seen the success that the groups have had working together in the U.S. and we’re trying to bring that ethos to other places by having regional summits where we can be a third party.” —Conversation with David Coman-Hidy and Andrea Gunn of The Humane League (2018)

“This year is the first year in which we have done something really formal, where our consultants volunteered to come in and work with us in putting together a very formal [strategic] plan. […] Now with the strategic goals that we laid out, we have all the metrics assigned to those, all the sub-goals that fall onto the various departments, and we are going to be assessing the plan quarterly.” —Conversation with David Coman-Hidy and Andrea Gunn of The Humane League (2018)

Hens in a cage-free environment may have opportunities for behaviors that seem likely to improve their welfare such as dust bathing, perching, foraging, and nesting, which are not available in battery cages. For a description of some of these potential welfare improvements, see the Open Philanthropy Project’s report “How Will Hen Welfare be Impacted by the Transition to Cage-Free Housing?”