Additional Analysis of a Study of Vegetarians

Humane League Labs published a large scale survey of vegans, vegetarians, and meat reducers in early 2014, focusing on finding out how and why people adopt diets that reduce their consumption of animal products. Their survey included 57 questions, which they asked of over 3,000 respondents. Although their initial report was long and detailed, since there was such a large number of questions, ACE wondered what else could be extracted from the data. We asked volunteers Zoe Gumm and Kevin Brennan to perform some additional analysis, and this blog post is based on their reports.

Resource use among new product limiters

One interesting feature of the study is that many questions allowed multiple responses per respondent, generally 2 or 3. The original report analyzed these questions by reporting the percentage of respondents who chose each answer. But they also allow for more complicated analysis that looks for connections between the possible responses. This can produce a large volume of data, and ensuring that all combinations are checked while statistical rigor is maintained is particularly difficult. So we looked for interesting qualitative patterns; we didn’t make any hypotheses before testing the data, and we wouldn’t interpret what we found as firm results.

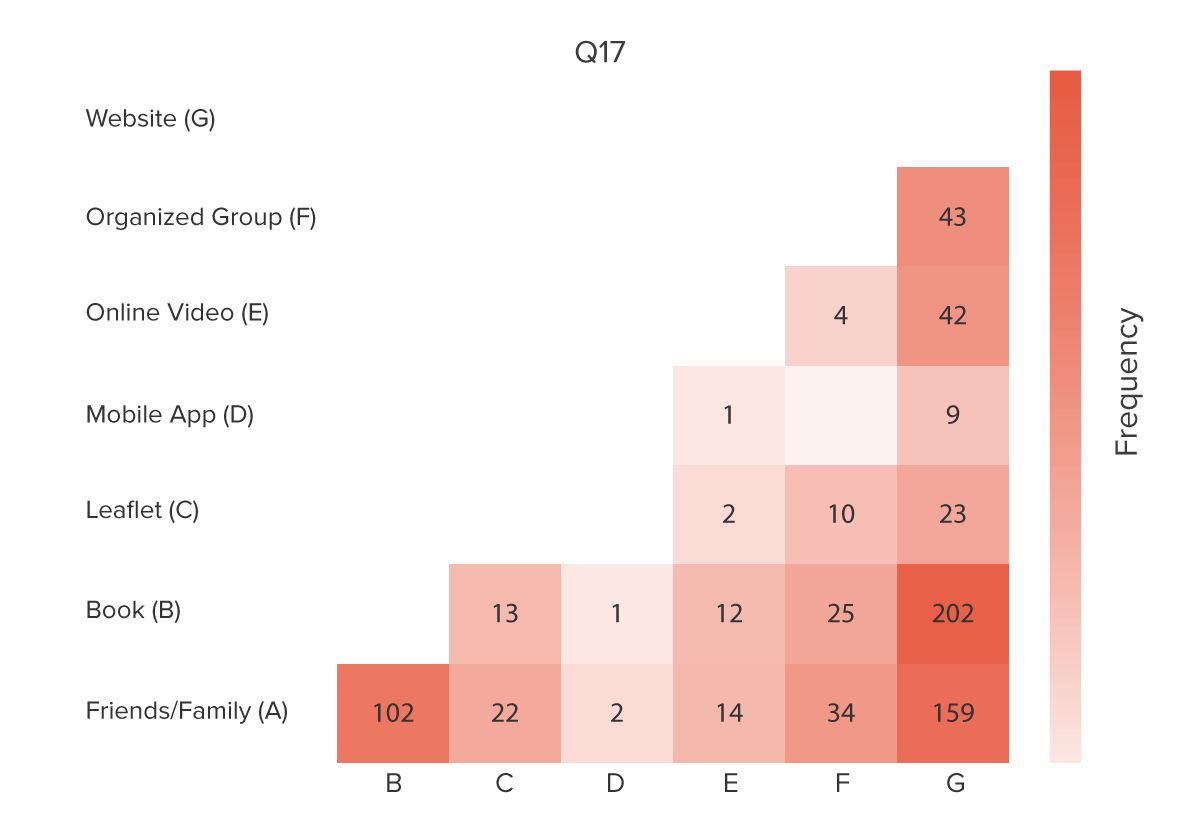

One question we considered was question 17 in the original report, “Which TWO of these resources/events were most helpful in learning HOW to reduce or eliminate animal products from your diet?” As presented in the original report, the response frequencies were:

- websites: 73%

- books: 58%

- friends or family: 43%

- online video: 17%

- pamphlets: 12%

- organized groups: 8%

- mobile app: 1%

We plotted the responses of people who chose two items from the list to try to determine if there were any patterns to the resources used that weren’t visible in the data as presented above.

Many sections of this chart look similar to what we’d expect from the original report, but there are some interesting features about the people who responded that organized groups had been helpful to them. Most noticeably, there are more of these people than we’d expect from the original breakdown; among people who had used two resources, more reported using organized groups than pamphlets or online videos, although each of those choices was more common than organized groups among the whole sample. It may be the case that organized groups provide their members with additional resources more effectively than other supports do, or that people generally find an organized group only through the aid of another more easily accessible resource. It would be interesting to see whether either of these hypotheses is supported by other studies and reports, especially given that groups of vegetarians and vegans not only support each others’ dietary habits, but also provide opportunities to become more engaged in advocacy.

Connection between animal and environmental motivations

An additional set of questions in the original report asked respondents, “If you have ever reduced or eliminated your consumption of animal products, to what extent did these factors inspire or influence your initial change?” and “If you are continuing to reduce or avoid animal products in your diet, which of these are your reasons for continuing to do so?” Factors listed included animal welfare, environmental, and health concerns, as well as reasons less often addressed by animal advocates such as human rights, religion, and the influence of family or friends.

Again, the original analysis reported simply the percentage of respondents who indicated that each factor had played a large role in their choice to limit animal product consumption. As other studies have found, the primary reasons cited were animal welfare, health, and the environment, in that order. But the format in which the question was asked also allows additional exploration. In particular, since we’re aware of concerns that promoting veganism and vegetarianism may also promote environmentalist (rather than anti-speciesist) values, we can use these questions to explore that concern.

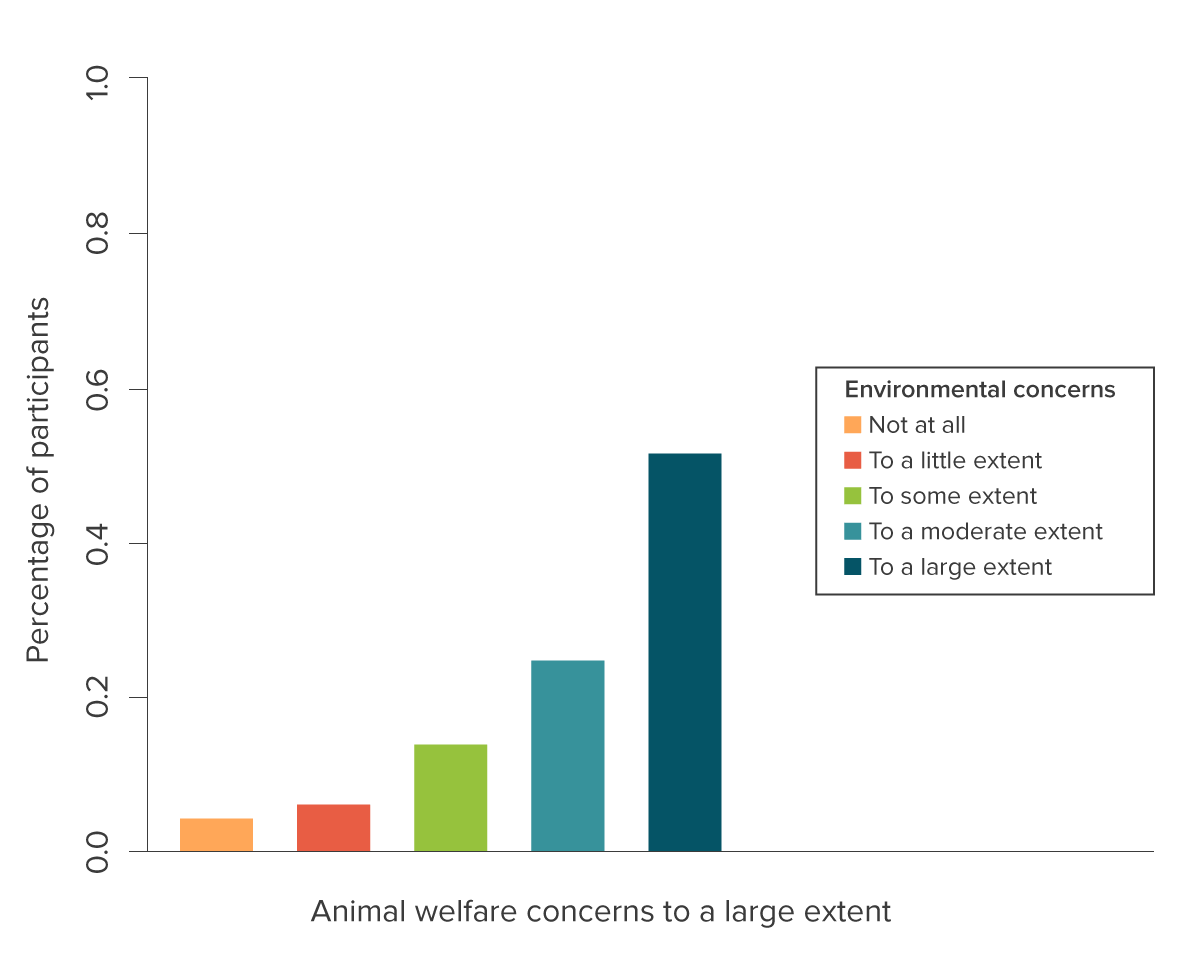

Initially, people who decide to limit their intake of animal products often have both animal welfare reasons and environmental reasons, as expected. Many respondents noted an equal concern for animal welfare and for the environment as factors influencing their diet choices.

Since we don’t know anything about respondents’ level of concern about each of these issues before changing their diet, we don’t know how much of the concern about either factor came directly from sources persuading them to go vegetarian, or how much was simply their initial inclination, which may have made them more likely to be persuaded in any case.

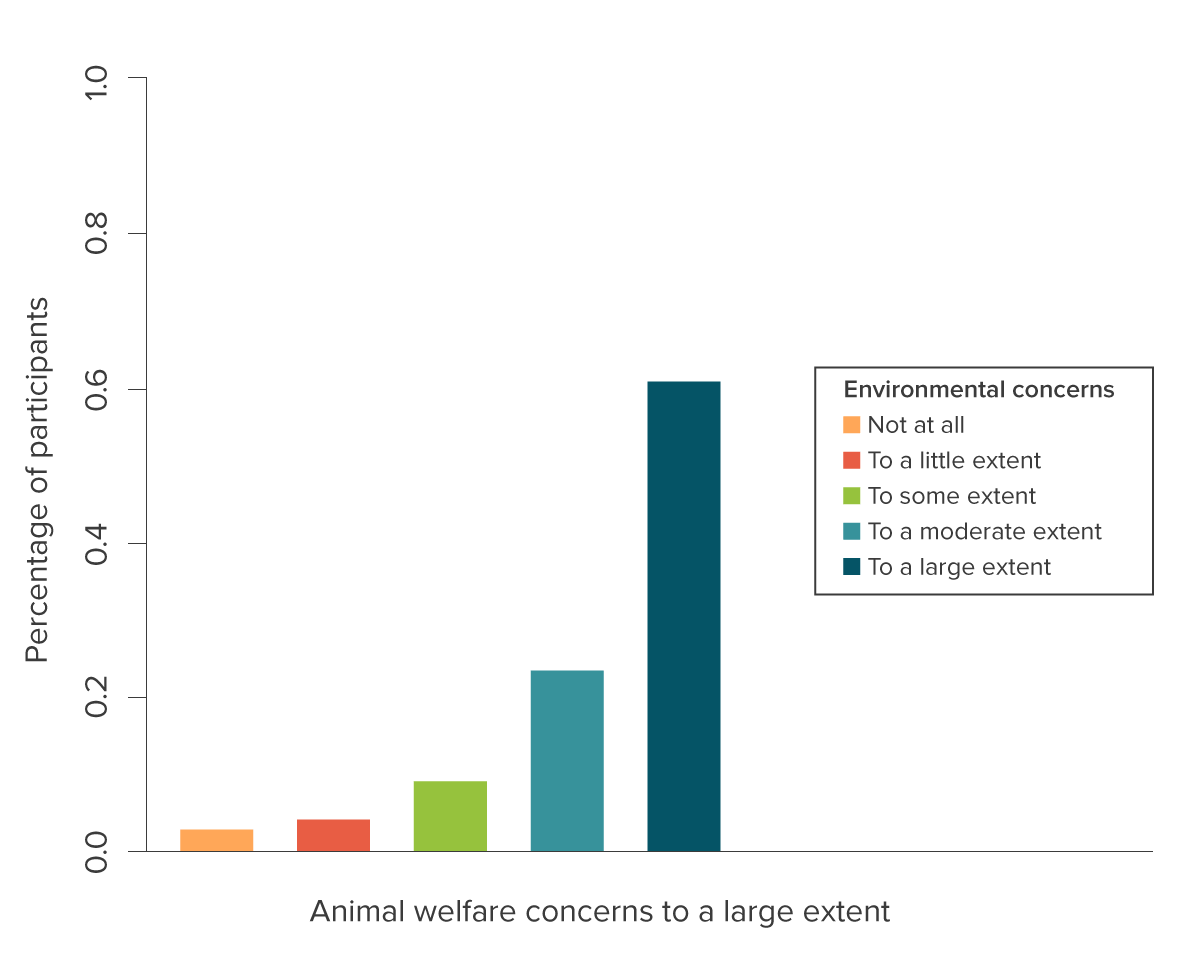

However, the initial choice to limit animal product consumption is not the end of the story. Values inform actions, but actions also inform values, which might lead to changes in what factors were reported as important in causing people to continue limiting their consumption. These changes are also important to understand. In theory, people who go vegetarian because of animal welfare concerns might come to have more environmentalist reasons for remaining vegetarian, a change we could use this survey data to tie to vegetarian advocacy.

In fact, the respondents in this survey did mention more factors as important to their decision to continue to limit animal product consumption than to their decision to begin limiting consumption in the first place. The increase is relatively balanced across animal welfare, health, and environmental reasons: an additional 7% of respondents mention animal welfare concerns, 10% more mention health concerns, and 7% more mention environmental concerns. The increased concern for the environment is matched by increased concern for animal welfare, even though animal welfare was already the most prominent reason for limiting animal product consumption.

Among those most motivated by concerns about animal welfare, however, the increase in concern about the environment appears to be larger than in the whole group of respondents. Since these are the same respondents we would most expect to be following or participating in animal advocacy, it may be the case that their concern for the environment was promoted by their contact with animal advocates. More analysis would be needed to establish a firm link, but this finding underscores the importance of paying attention to how we as animal advocates discuss the environment and animals in the wild.

This blog post, and the analysis we did before writing it, used only a small fraction of the data available in the original study. We’re sure that more questions could be investigated using the data that the Humane League Labs collected. Since all their data is freely available, we encourage you to generate your own questions and look for the answers – or post them in the comments, to inspire someone else!

Filed Under: Research Tagged With: interventions, numbers

About Allison Smith

Allison studied mathematics at Carleton College and Northwestern University before joining ACE to help build its research program in their role as Director of Research from 2015–2018. Most recently, Allison joined ACE's Board of Directors, and is currently training to become a physical therapist assistant.