Prioritizing Between Farmed and Wild-Caught Fishes

Prioritizing Between Farmed and Wild-Caught Fishes

There are various ways animal advocates can help fishes: the group of vertebrate animals killed in the highest numbers for human consumption. While interventions to decrease animal consumption or increase the availability of animal-free products can help both farmed and wild-caught fishes, prioritizing between the two can help determine how to improve fish welfare most effectively. Here, we use the scale, tractability, and neglectedness framework to prioritize between farmed and wild-caught fishes.

Scale

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) does not provide data about the numbers of individual farmed and wild-caught fishes; they only provide data in tonnes or other volume units. To estimate the number of individual fishes, we used the FAO’s volumetric data and data about average fish size. Because average fish size varies by species,1 sex, age, and region, estimates of the number of individual fishes can vary widely depending on the data used.

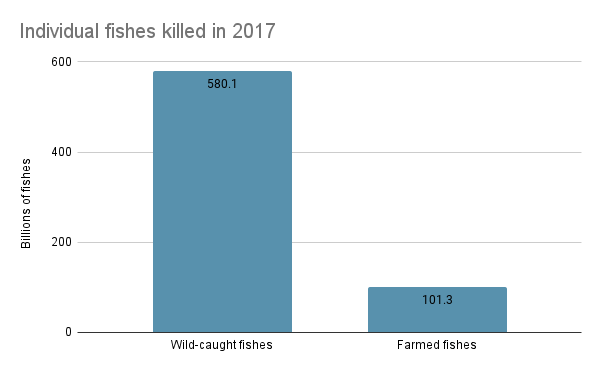

One estimate suggests that between 0.79 and 2.3 trillion wild-caught fishes were killed annually from 2007 to 2016, while between 51 and 167 billion farmed fishes were killed in 2017. ACE’s conservative estimate suggests that 580.1 billion wild-caught fishes and 101.3 billion farmed fishes were killed for human consumption in 2017. These numbers suggest that wild-caught fishes are the group of vertebrates killed the most for human consumption globally, followed by farmed fishes.

Fig 1. Individual fishes killed in 2017

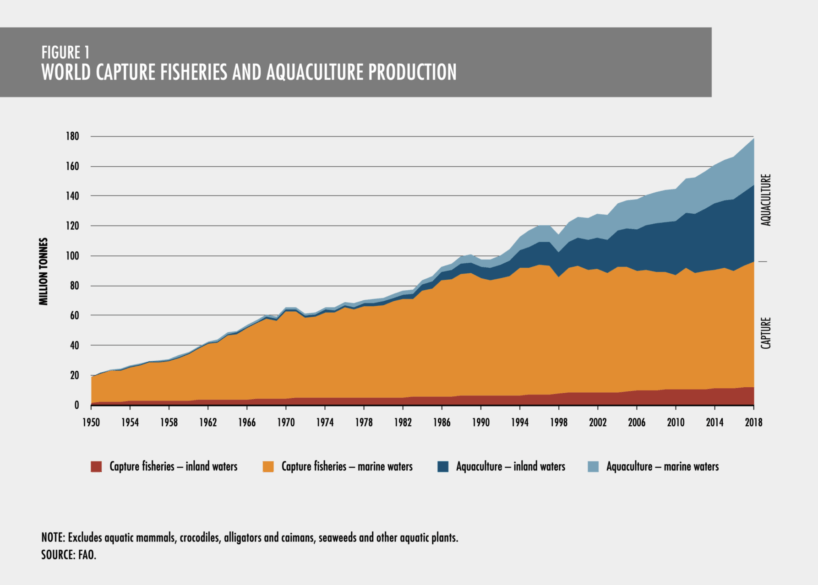

The global volume of wild-caught fishes has been relatively static since the late 1980s, while the global volume of farmed fishes has been steadily increasing since the 1950s.2 With wild-catch fishery production stagnating, aquaculture (i.e., fish farming) has been the primary driver of growth in the global supply of fishes— it is now the fastest-growing food production industry in the world.3 If current trends continue, there may be more farmed fishes than wild-caught fishes within the next few decades. Considering that the global aquaculture industry is not yet as established as the land animal agriculture industry,4 it seems particularly impactful to intervene in the early stages of the aquaculture sector.

The following chart is based on the FAO’s data. It shows the historical production of aquaculture (including farmed fishes and other animals)5 and fisheries6 in tonnes.

Fig. 2. World capture fisheries and aquaculture production (excludes aquatic mammals, crocodiles, alligators and caimansm and other aquatic plants). Adapted from “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020” by FAO, 2020, p.4, https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca9229en

Tractability

Although wild-caught fishes are currently far more numerous than farmed fishes, helping wild-caught fishes may be relatively less tractable than helping farmed fishes. Effective and reliable promotion, implementation, regulation, management, and monitoring of responsible fishing practices seem particularly challenging for wild-caught fishes.7 Other challenges to helping wild-caught fishes are similar to those for helping wild animals in general, as humans have much less influence over the conditions that impact the welfare of fishes in the wild. Improvements to wild-caught fish welfare have focused on reducing animal suffering during and after capture,8 but we are currently uncertain about ways we can help them before they are caught.

There is more extensive research on the welfare of farmed fishes. Specific ways of improving farmed fish welfare include improving welfare standards during capture and killing, and improving environmental conditions on farms (e.g., managing dissolved oxygen levels and providing environmental enrichment).9

Neglectedness

Both farmed and wild-caught fishes are highly neglected, as most animal advocates focus their efforts on other animal groups. In the last few years, organizations have been increasingly targeting fishes—we hope this trend continues. From our knowledge of the animal advocacy movement, we believe that both farmed fishes and wild-caught fishes are equally neglected; therefore we do not consider neglectedness a determining factor in prioritizing between these two groups.

Conclusion

Although wild-caught fishes are more numerous than farmed fishes, we believe the welfare of farmed fishes may be more tractable because farmed fishes spend more time under human control. Therefore, we have more control over conditions that affect their wellbeing. Based on available data on historical trends in production, we believe that the number of farmed fishes in the future will exceed the number of wild-caught fishes if trends in production continue along similar trajectories.

To view all of the works cited in this report, see the reference list.

ACE previously concluded that there are at least 262 species of farmed fishes and 1,373 species of wild-caught fishes killed for human consumption.

The data includes crustaceans, diadromous fishes, freshwater fishes, marine fishes, frogs and other amphibians, turtles, squids, cuttlefishes, and octopuses.

The data includes crustaceans, diadromous fishes, freshwater fishes, marine fishes, crocodiles and alligators, frogs and other amphibians, turtles, whales, seals, and other aquatic mammals.

Filed Under: Animal Welfare

About Maria Salazar

Maria initially joined ACE as a research intern in September 2017 and was excited to rejoin ACE as a Researcher in July 2019. She holds a bachelor’s degree in ecology and a master’s degree in applied and professional ethics, and has several years of experience managing and developing outreach and research projects at local and international animal advocacy charities.